Publications An Appetite For M&A: How Food Companies Can Buy And Sell Their Way To Competitive Advantage

- Publications

An Appetite For M&A: How Food Companies Can Buy And Sell Their Way To Competitive Advantage

By J. Neely, John D. Potter – Strategy&

Executive summary

Food companies, faced with new and challenging market forces, are changing their strategic approach to growth. For many, this is underscored by a focus on capabilities as a driver of how to organize and operate their businesses for competitive advantage. For winning companies, this focus on capabilities is informing their growth path, including how they approach mergers, acquisitions, and divestitures.

The forces of change

The competitive landscape for the food industry is almost unrecognizable compared with what it looked like just a decade ago. Small niche players are finding their way into Walmart, Kroger and other large retailers where they are going head-to-head — and winning — against established food giants. Many of those giants have split themselves into smaller businesses in order to better focus how they go to market. Where once “bigger is better” sufficed for a strategy, today companies face a host of challenges that are pushing them to rethink their business models:

Low growth in mature markets: The recession dealt a body blow to the food industry, and its after-effects are still being felt. Overall consumption in the United States has been largely flat for several decades, increasing only at the same rate as the population, and this is expected to continue. During the recession, besieged consumers rapidly migrated to value, driving growth of private labels in many segments, and putting extreme pressure on manufacturers and retailers to maintain or even reduce prices. This demand pattern has remained stubbornly unchanged as real wages have increased very little for the vast majority since the start of the recession. Sluggish growth will be only partially offset by increased demand in emerging markets.

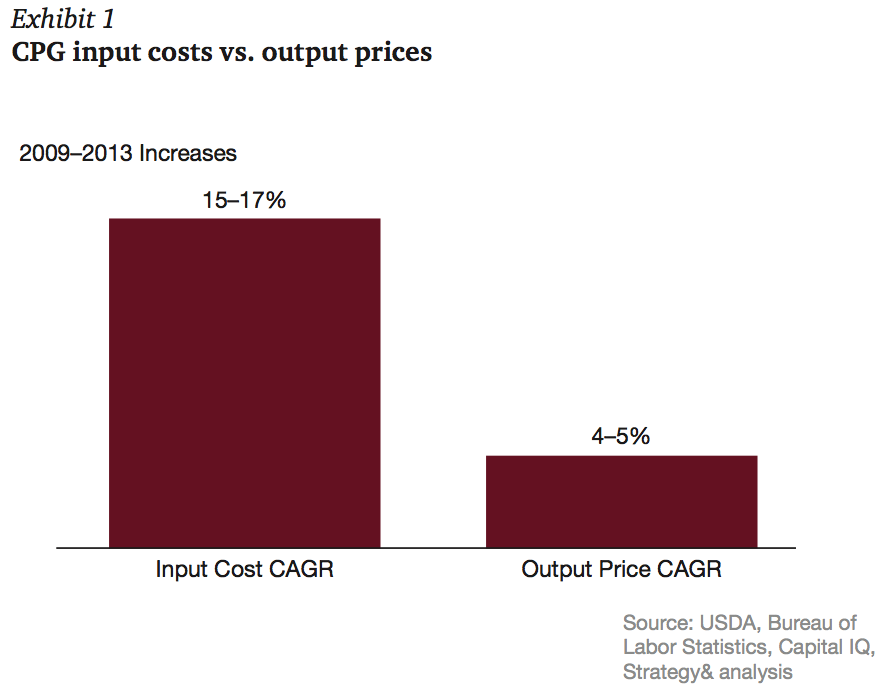

Pressure on margins: Volatile commodity prices also placed pressure on already thin margins. Consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies were not successful at passing these input costs on to consumers during the recession (see Exhibit 1: CPG input costs vs. output prices). While commodities have retreated from peaks, offering some relief, manufacturers are also having to adjust to a world in which consumers are able to use digital price comparison services to effortlessly find the best value. This has further impeded their ability to raise prices.

Where once “bigger is better” sufficed for a strategy, today companies face a host of challenges that are pushing them to rethink their business models.

Morphing and divergent consumer preferences: Today consumer tastes can change with lightning speed, intensified by the enormous influence of social media. In addition, there has been a bifurcation of the consumer base. On one end are the “selectionists”—consumers who are willing to pay more for higher-quality items, especially those emphasizing health and natural ingredients. On the other are the “survivalists” — consumers who are still reeling from the recent economic downturn and who continue to seek out products that offer the best value. Catering to the needs of increasingly divergent consumer groups only adds to the complexity that companies must navigate.

Changing retail landscape: Despite a decade of declining productivity, supermarkets plan to add an additional 290 million square feet of retail space by 2025. This is also an environment where traditional channels are becoming less important for food sales. Faster-growing retail formats, including dollar stores, convenience stores, and even drug stores are all getting in on the action. Online purveyors are also becoming significant competitors, and are expected to command 10 percent of the market by 2025. Each of these channels has fundamentally different go-to-market and trade requirements, and today’s food companies must support each of them to remain competitive.

Intensifying competition from small, nimble players: Perhaps the most dismaying trend of all for large, diversified food companies is that scale is losing its value. Small brands are able to compete effectively by outsourcing functions and developing relationships with big chains that sell to a large percentage of the market. In fact, many of these chains are actively pursuing relationships with smaller brands.

Each of these channels has fundamentally different go-to-market and trade requirements, and today’s food companies must support each of them to remain competitive.

Combined, these trends have adversely affected food industry performance. Between 2010 and 2013, annual revenue growth was 6.9%, while earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) grew at 5%. Furthermore, more than a third of the industry had declining EBIT (see Exhibit 2: Food company performance). To get the growth needle moving more quickly, food companies will need to think very differently about where and how they can win.

Is it time to think differently about growth? Capabilities-driven strategy

The numbers tell the story: It’s no longer an asset-based game. Large, diversified food companies are struggling to compete with smaller, more focused enterprises. To excel in the marketplace, these companies need to be thinking beyond scale about what it is they do better than anyone else.

For example, one leading snack food company in the United States has built up an efficient direct-to-store delivery system that can reach even the tiniest channels. It uses small trucks that take smaller orders to outlets like convenience stores and gas stations, and it has devised a logistics system that allows it to do this economically. The ability to service channels of this size gives the company enormous control over what goes on the shelf and how much shelf space it gets versus competitors that use a different, less accommodating delivery approach. The company is purposefully focused: it is careful not to expand into items like beverages or heavy products with slow turns that would tax its delivery capability. As a result, the company can reach more outlets than the competition and achieve higher consumption of its products at very attractive margins.

What this company has done is use its capabilities as the foundation of its go-to-market strategy. In fact, it has focused much of its energies on finely tuning a “capabilities system” — a handful of things that it is able to do extremely well that set it apart from the competition. When companies tie together their capabilities system with their value proposition to customers and the products and services that fit with that value proposition, they are able to achieve a coherent, capabilities-driven strategy.

We see many industries reorganizing around capabilities, including the CPG industry, with the strongest ones emerging as “super- competitors.”

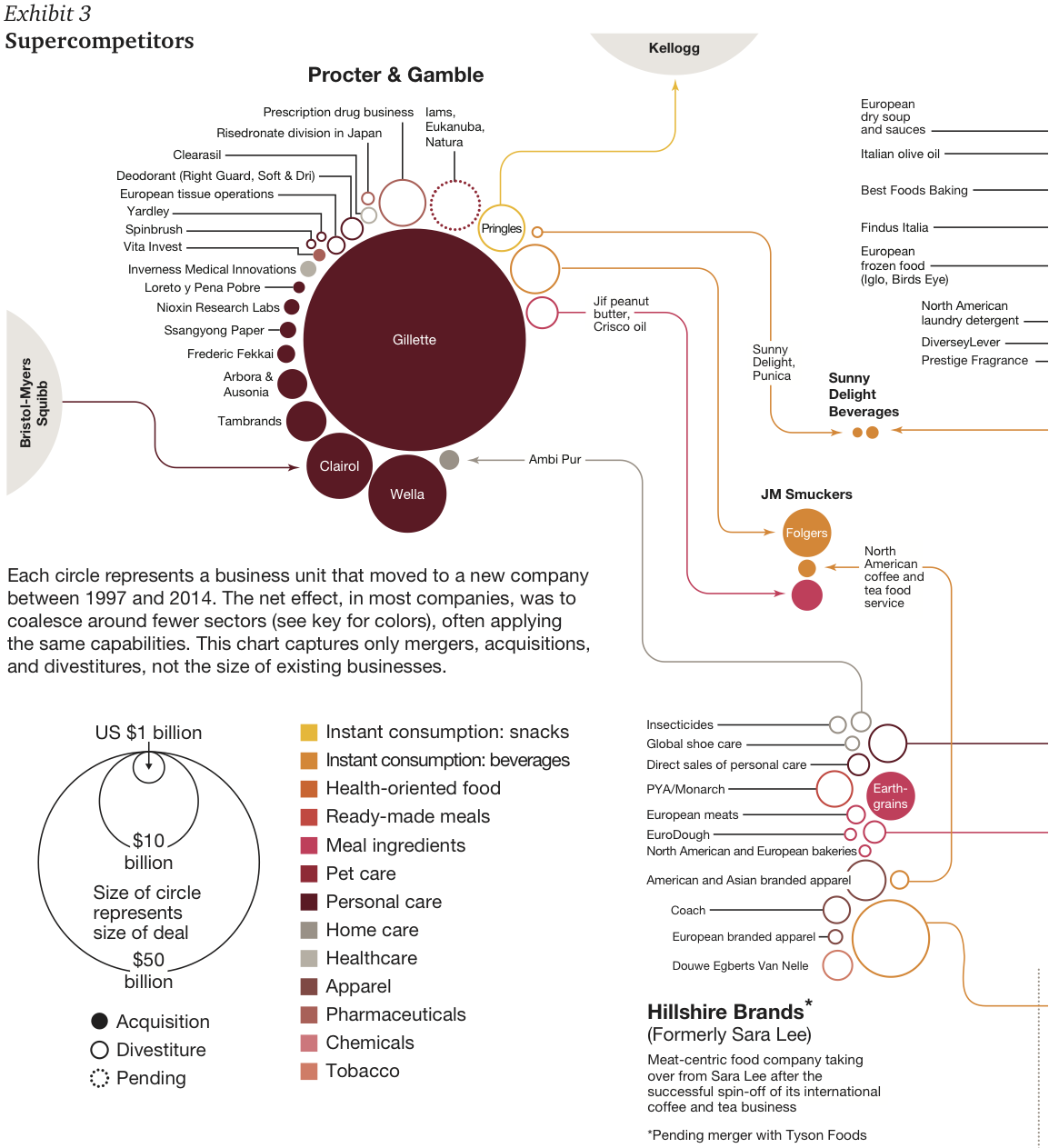

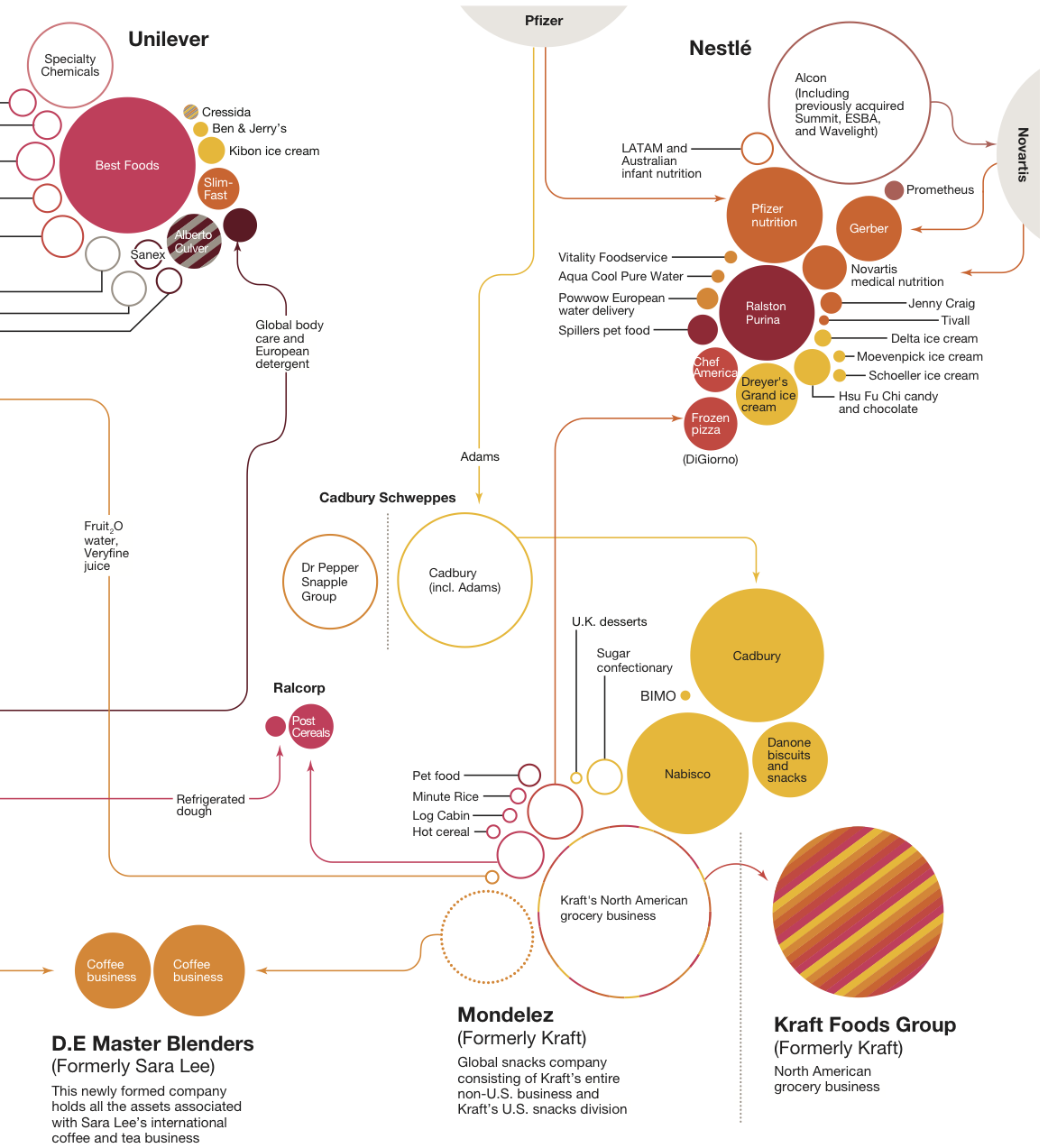

In fact, we see many industries reorganizing around capabilities, including the CPG industry (food and non-food), with the strongest ones emerging as “supercompetitors.” For instance, CPG giant Procter & Gamble divested its food products over the course of a decade, and focused players like Smucker’s picked them up and placed more focus on them. Sara Lee shed its apparel business to become a diversified food company and then went further, breaking into smaller components, each with its own capability system. It spun off its breads to other bakery businesses and finally separated out its meats and coffee businesses, both of which have been acquired by or combined with companies that have strong capabilities in these segments (e.g., Hillshire, now merging with Tyson) (see Exhibit 3). Kraft also recently split into a grocery-focused and a global confection-focused business in part based on a capabilities argument.

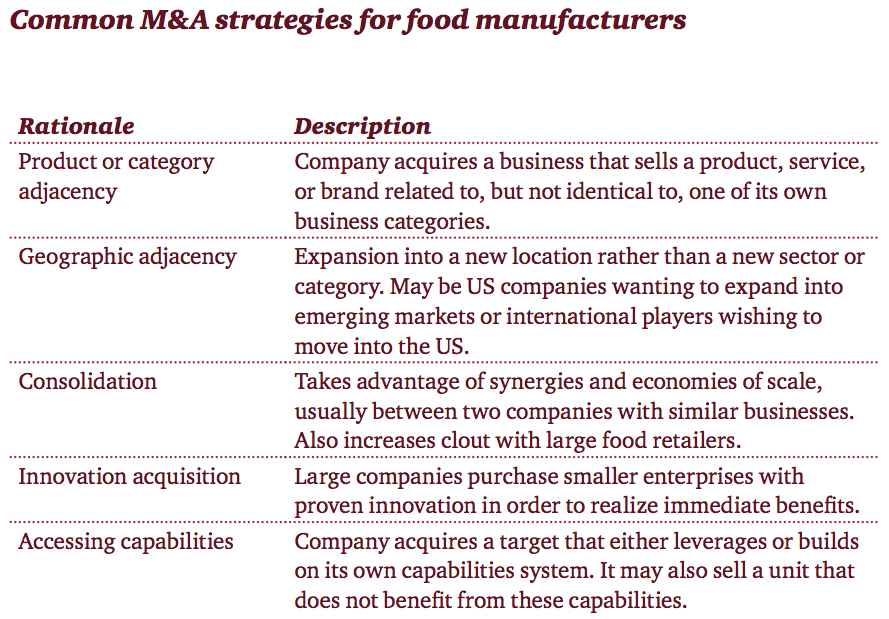

Reorganizing around capabilities has profound implications for how companies choose to focus their growth initiatives, including their M&A strategies. Companies pursue mergers and acquisitions for a variety of reasons. These strategic drivers include product or category adjacency, geographic adjacency, consolidation, innovation acquisition, accessing capabilities (for descriptions, see box: Common M&A strategies for food manufacturers).

Yet not every transaction is a home run. What is the secret sauce that makes a deal successful? We conducted an analysis of deals completed in multiple industry sectors over the course of more than a decade. We categorized each deal — regardless of its primary rationale — based on the degree to which the capabilities of the target were a good fit with the capabilities system of the buyer:

- Enhancement deals: The acquiring company adds new capabilities to fill a gap in its existing capabilities system or to respond to a change in its market.

- Leverage Deals: The buyer takes advantage of its current capabilities system by applying it to products and services from the target company, often improving the target’s performance. It applies these capabilities to new customers, geographies, products or services.

- Limited-fit deals: The deal ignores capabilities and does not improve upon or apply the acquiring company’s capabilities system in any major way. Sometimes these deals even bring the buyer a product or service that requires capabilities it doesn’t have.

Not surprisingly, limited-fit deals generally fared the worst, and in many cases they actually destroyed value. On the other hand, companies that factored capabilities fit as part of the strategic rationale and ideal decision-making tended to realize better returns. The biggest premiums generally resulted from deals that leveraged the acquiring company’s already well-established capabilities system.

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in the food and beverage sector have accelerated in recent years, with more than 200 announced US deals over $50 million in the last five years, totaling about $235 billion (Thomson Reuters, PwC analysis). As this volume builds, and driving forces such as shareholder activism, low interest rates, strong balance sheets, and strong competition for targets prompt more players to pursue deals, valuations will continue to climb. This makes it more important than ever that companies realize maximum value for these transactions, and focusing the strategic rationale on capabilities fit is one effective means of doing so.

Using a capabilities mindset for portfolio optimization

The starting point is ongoing portfolio evaluation to determine which assets are core to value-creating and which may prove more valuable in the hands of a different owner. Portfolio optimization requires proactively identifying these businesses and positioning them for the optimal buyer before entering into a formal sale process. When focused on the capabilities that drive value in the business, companies can improve their chances of commanding the best price, increase speed to market, extract their expected value, and re-focus on the core business. This also sets the basis for prioritizing what should be added to the portfolio and assessing build versus buy options. With a clear view of how capabilities will support the future portfolio, companies can have a comprehensive map for what to sell over time, what targets they will pursue for acquisition, and what organic activities to put in motion in the meantime.

Using a capabilities mindset to identify and evaluate acquisitions

Achieving capabilities fit in an M&A transaction is not always easy, even when the deal is specifically designed to acquire or build on a company’s capabilities system. Take the recent case of a frozen food company that made the decision to acquire what it thought was a related frozen business. The company’s rationale for the acquisition was that it would be able to leverage its production and distribution capabilities in the frozen category. As it turned out, there were some unique differences in processing and handling that made this difficult to do, setting the timeline for value realization back and limiting some of the expected synergies.

So how does a company go about determining whether a transaction will leverage or enhance its capabilities system? It starts with self-knowledge: having a deep understanding of the three to six things the company does extremely well that comprise its capabilities system. Without that, the company will find it difficult to know whether an acquisition is a good fit or whether an existing business is a poor one.

Capabilities-building should be central to M&A strategy, regardless of whether it is the rationale for every transaction. Companies need an understanding of what kinds of opportunities will leverage or enhance their capabilities systems. This means thinking about capabilities at the earliest stage of the process.

Capabilities-building should be central to M&A strategy, regardless of whether it is the rationale for every transaction.

Executing the deal successfully

Once a target has been identified for acquisition or sale, successful execution of the transaction calls for a robust deal process that helps the dealmaker assess and deliver the expected value — a simple concept, yet difficult to achieve. On the acquisition side, injecting a capabilities focus into the deal process will move the company toward consideration of such important issues as what is unique about the target’s capabilities system and how it uses those capabilities to create value for customers (see sidebar). A capabilities mindset is also important to post-deal planning, as the buyer sets out to integrate the target organization and determine how to allocate future investment.

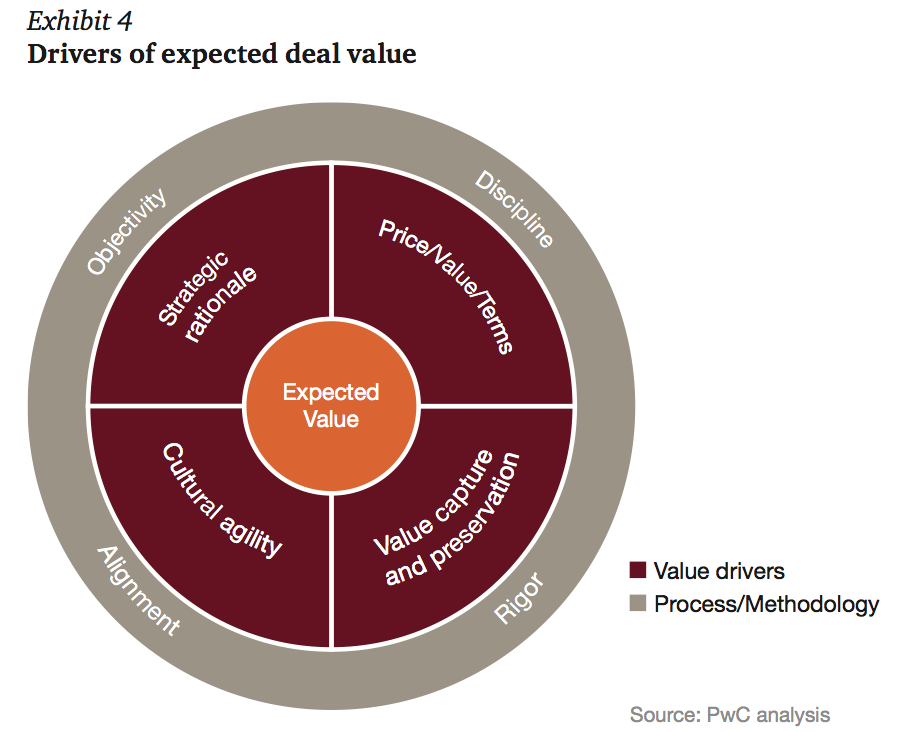

But the deal execution process must also focus on all the drivers of expected value. By using each of the following four drivers (see Exhibit 4) as a lens to evaluate the validity and soundness of the deal, and consistently using those lenses throughout the transaction process, the deal team will increase its ability to close a successful deal that realizes its potential:

- Strategic rationale: Strategic rationale is the reason the company has decided to do the deal in the first place. Buying the target company must advance the acquiring company’s strategy and, as discussed in this paper, deal success will increase if the target’s capabilities align with and enhance those of the buyer. Reinforcing that alignment throughout the deal process is what truly drives success. For food companies, accelerating to meet divergent and changing consumer preferences is critical. Buyers in this sector will look for targets that have innovation capabilities that not only enhance their own, but are focused on value creation from future products.

- Cultural agility: Cultural fit is often cited as a requirement for a successful deal. But no two organizations will be completely aligned when it comes to culture, especially those that have evolved over many years. The two organizations need to be adaptable enough so that the target organization can be assimilated without stifling those cultural elements that are crucial to value generation.

- Price and terms: Negotiating the price and terms of the deal is where the rubber meets the road. The deal team goes into the transaction process with a set price their company is willing to pay and the terms they are prepared to extend. As the diligence process unfolds, they will uncover a great deal of new information. Some of it may have serious implications for the proposed purchase price — for example, the discovery that the target company has a large unpaid tax liability. Other information will simply be a distraction. The deal team needs to be able to screen out irrelevant information and only consider what is important to the negotiation itself.

- Value capture: An important rationale for the deal is a belief on the part of the acquiring company that it is uniquely positioned to increase the value of the target organization over what it is currently able to deliver. In the food business, scale and route to market are important, but value will accrue more quickly with a focus in both enhancement and leverage deals. The deal process needs to explore the original assumption in greater detail and test the validity of expected value-generation strategies.

The deal team enters the negotiation process with a hypothesis of why the deal makes sense. It is not uncommon to see the initial deal hypothesis become a given, with deal teams focused on proving it right. This approach tends to be both rigid and static. An effective process, on the other hand, is fluid and iterative. It attempts to prove the hypothesis wrong by continually revisiting assumptions and incorporating information that might challenge the business case for the deal. This means the team must be objective and cognizant enough of their blind spots that they can overcome any inherent biases. At the same time they need to be vigilant about filtering out extraneous information. Using the four drivers as evaluative lenses will help the team will make more informed decisions and stay focused on expected value. An objective, disciplined, rigorous process that aligns priorities will ultimately help meet a buyer’s expected value.

It is not uncommon to see the initial deal hypothesis become a given, with deal teams focused on proving it right.

Diligence with a capabilities mindset

- What is unique about the target company’s capabilities system? How does it create value for customers?

- How does the target company’s capabilities system differ from our own?

- If we are buying the company for its product and services portfolio (a leverage deal), are we sure that those products and services will thrive within our current capabilities system?

- If we are acquiring the target company for its capabilities (an enhancement deal), will we be able to preserve and integrate them?

- How will this newly integrated entity deploy and execute its evolving capabilities system? What are the risks of a poor strategic fit?

- Which facilities, processes, suppliers, and employees are critical to bring on board, for the sake of a separated, combined, or integrated capabilities system? Are any of them (or any key customers) vulnerable to poaching by competitors?

Conclusion

M&A is likely to become increasingly important, not just in growing food companies, but in streamlining and focusing them. Making capabilities-building the foundation of a robust deal decision-making process will not only improve the likelihood of transaction success — it will also better equip companies to compete in today’s hungry food marketplace. Once a strategic rationale is set, a robust and objective deal process that addresses and reiterates the value drivers of the deal — i.e., strategic rationale, cultural agility, price and terms, and value capture — will ultimately help food companies achieve their expected value. Getting those deals right is important. Not only do investors tend to judge companies harshly when deals fail to achieve their objectives, but gaining and keeping a competitive advantage is critical in ever-evolving industries.

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter