Publications Post Acquisition Integration Handbook

- Publications

Post Acquisition Integration Handbook

By: Baker & McKenzie

Post Merger Integration Handbook

SECTION 1: Optimizing Value in Multinational Corporate Acquisitions

Companies active in the mergers and acquisitions market are realizing that the real challenge when acquiring a new business starts only when the deal closes and are focusing more attention on how they best derive value from their acquisitions. Where the existing and target businesses operate in the same or complementary fields, it is almost always the case that the acquiror desires to integrate the two businesses in order to save costs, develop synergies and generate value for its shareholders.

Bringing together businesses with different trading relationships, histories and cultures inevitably poses substantial challenges. Where the businesses of the acquiror and target are multinational, the scale and number of those challenges increase significantly.

The aim of this Handbook is to provide a reference tool for companies which may either be contemplating, or in the process of executing, a multinational business acquisition, and which therefore need to focus, at an early stage, on how best to overcome these challenges and deliver maximum value to shareholders from the acquisition. It provides a guide to the process of identifying the legal issues to be addressed, planning the business integration and its legal implementation.

The following chapters focus on the common situation where the parent company of one multinational group acquires all of the shares of the parent or intermediate holding company of another multinational group. This creates a corporate structure containing two completely separate groups of international subsidiaries, with the likelihood that in many territories the newly enlarged group will have duplicate operating and holding companies. These individual companies will have their own separate management structures and customer relationships and their own existing trading and intra-group arrangements. Integrating these structures, relationships and arrangements in the post-acquisition environment can prove to be one of the most significant challenges that management will have to face.

The issues raised in this Handbook may apply to acquiring groups headquartered in any jurisdiction, though a number of examples highlight issues particularly relevant to acquirors headquartered in the United States.

The key to developing a post-acquisition integration plan, implementing it successfully, and overcoming the challenges referred to above, is the early identification of the key strategic and business objectives of the acquisition and the subsequent integration. Provided that these objectives are realistic and supported by management, and provided that proper attention is given to the planning and implementation of the integration, the likelihood of delivering the desired benefits from the acquisition and integration of a target business will be increased.

SECTION 2: Executing a Post-Acquisition Integration Strategy

This section provides an overview of the type of integration process that typically ensures success in global post-acquisition integration projects, and then provides a brief summary of the more common substantive issues companies are likely to encounter in planning and implementing such projects.

Several of the key issues discussed in this overview are expanded upon in subsequent sections of the Handbook.

1. Overseeing the Execution of Post-Acquisition Integration

A large post-acquisition integration project raises issues of both process management and technical expertise. Moreover, once an integration plan has been developed, practical implementation issues will often prove critical in determining how quickly the plan can be implemented and how soon the benefits of the integration can be realized. In particular, human resource concerns, corporate and tax law issues, regulatory approval and filing requirements should be built into the planning process itself, and not be left to the implementation phase, with particular focus on avoiding road-blocks that might otherwise delay or frustrate the realization of integration goals in many jurisdictions.

Outside advisors are typically used in this type of project because of their specialized experience and expertise, and because a company’s permanent staff often are best used in other ways that relate more directly to the daily business operations of the company. However, internal staff are the best (indeed, for the most part, the only) source of the information that is critical to creating an effective implementation plan. In particular, they understand the historical perspective of the tax, corporate and business planning background of many of the existing structures. Ultimately, they must be sufficiently familiar with the new plan so that they can assist in both its implementation and be in a position to manage and sustain the structure that results at the end of the process.

Outside advisors and management must therefore work together to strike a balance that makes the best use of internal resources but adds the particular experience and expertise of the outside advisors and relieves the strain on already scarce management time. Frequently, however, this balance is not struck and advisors and management adopt one of two extreme approaches: the “black box” approach, whereby outside advisors gather data, disappear for some period of time and then present proposals, which can fail to take advantage of existing background knowledge possessed by management and, by excluding them from development of the plan, does not put management in a position to manage the end product; or the “shotgun” approach, whereby outside advisors gather minimal data, and then subject management to a barrage of ideas that “might” work, which effectively puts too much of the onus on management to place the ideas into the context of their group’s actual circumstances (of which the advisors are unaware) and assess resulting risks.

Although there is no “one size fits all” integration process, a happy medium can often be achieved if it is first understood that identification of the group’s strategic objectives is predominantly a senior management task, and that designated key management personnel should continue to be involved in both a fairly comprehensive information gathering phase and in strategic and tactical decision making during the ensuing analysis phase. In addition, the appropriate management personnel should be involved in the construction of any financial models necessary to understand the tax impact of the ideas generated by the project team

Ideally, there should be an interim evaluation of a preliminary plan to provide important feedback from the company on practical feasibility (including analysis of the impact on IT systems), risk appetite and business impact, followed by at least two opportunities to review the overall plan.

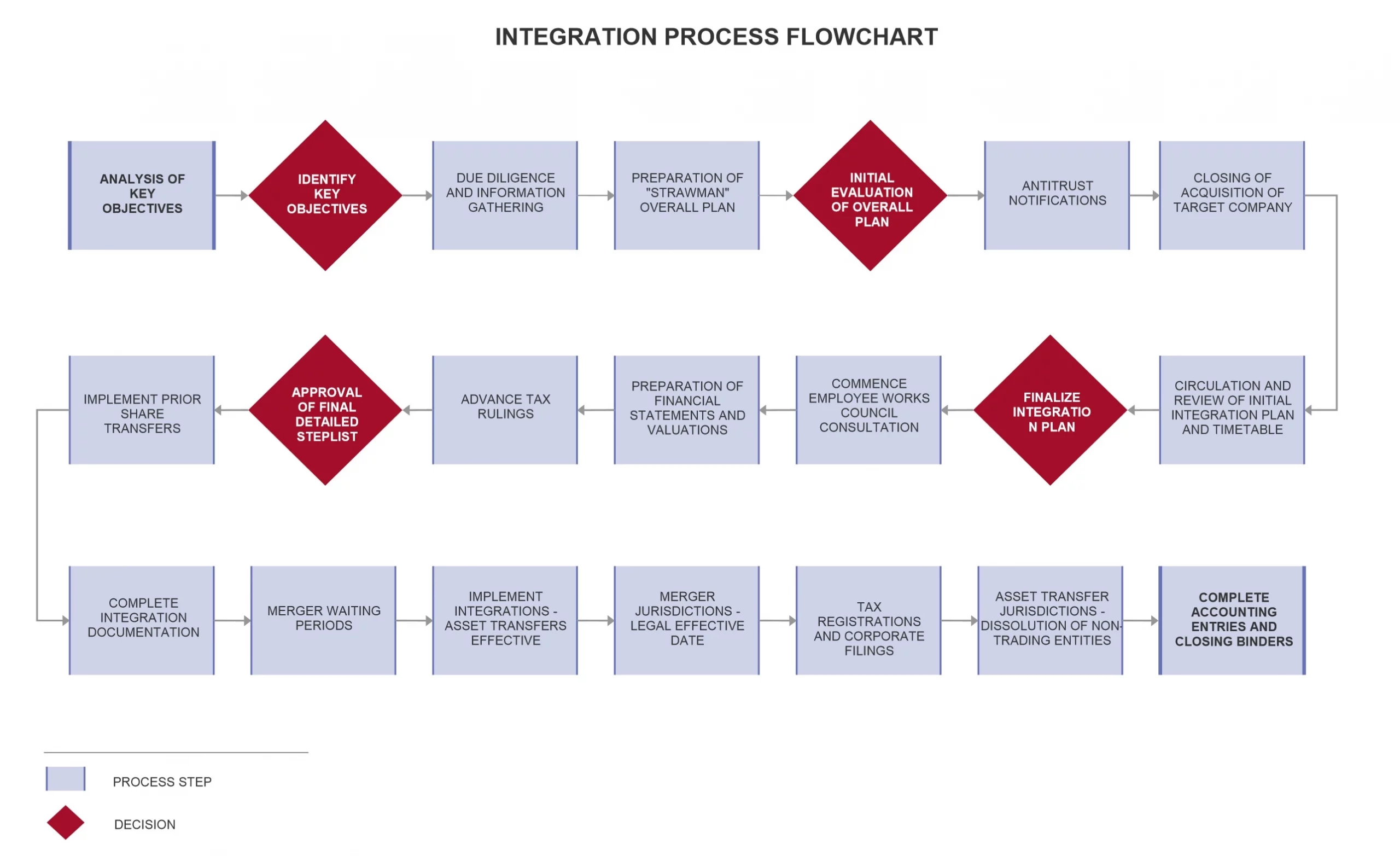

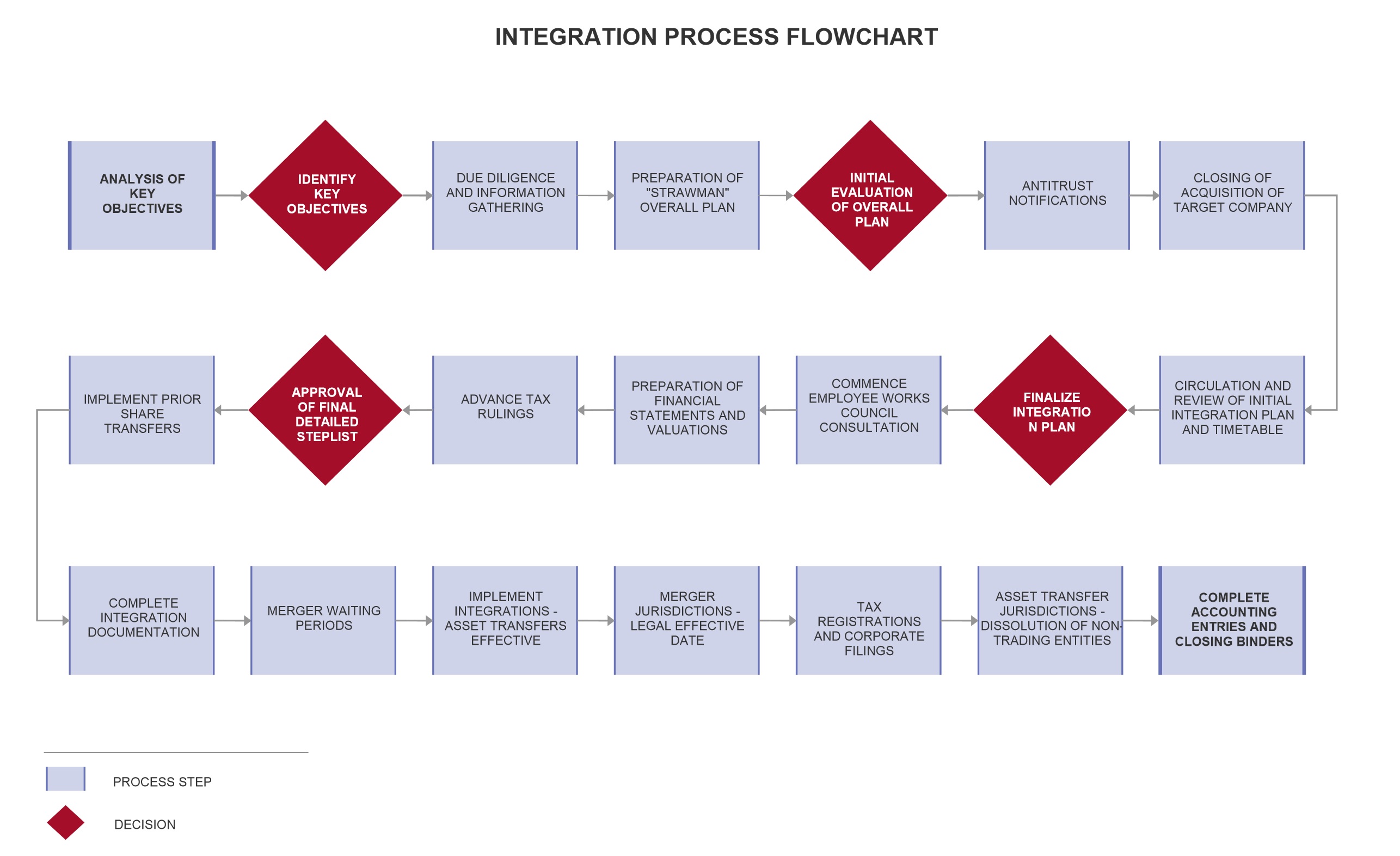

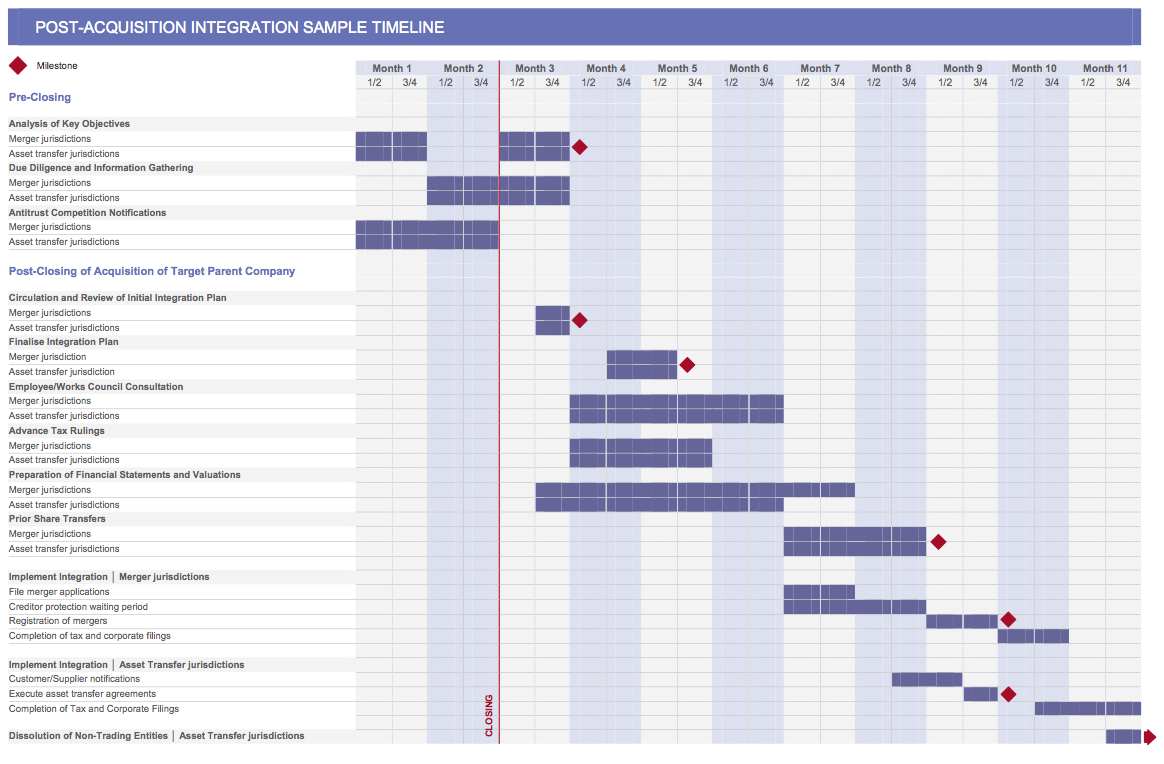

The process can be broken down into seven phases:

- identification of strategic and key objectives;

- information gathering;

- preliminary analysis and overall plan development;

- initial evaluation of overall plan;

- final detailed steplist development;

- evaluation and approval of final detailed steplist; and

- implementation of detailed final

1.1 Identifying Strategic and Fundamental Goals

The management team will need to decide the relative significance of business goals, timing and implementation, and prioritize accordingly. It may be that certain geographic regions or lines of business warrant first attention and the integration would then proceed on the basis of a planned series of iterations. Alternatively it may be that what is required is a comprehensive solution that pursues all regions or business units simultaneously with, to the extent possible, a single effective date for the entire integration. Naturally, the more comprehensive the initial plan, the more time it will take to move through the phases of the process.

The key issues to focus on are:

- what are the company’s business goals and priorities in the integration?

- what are the company’s plans for employee transfers and workforce reductions, if any?

- what are the constraints on moving assets, entities and people?

- what are the timing and sequencing priorities?

1.2 Data Gathering Phase

This process must provide for planned, structured input from all relevant constituencies, for example human resources, tax, general counsel’s office, strategic business development, finance and information systems. Whilst this adds some time to the process of developing a plan, it will pre-empt problems that could otherwise arise in the implementation phase in case a previously uncirculated plan should prove unacceptable to one or more of these constituencies. It is often the case, for example, that information systems compatibility issues can hold up the integration of newly-acquired entities into an acquiring group’s existing or newly designed commercial structure and the time required to resolve these issues will need to be built into the overall integration plan. The object of this phase is to develop a clear understanding of the goals of the integration project and to gather sufficient information and documentation about the entities and assets that are to be integrated in order to allow the planning and execution phases to proceed.

The initial information gathering phase of an integration project typically involves seeking answers to the following questions:

- in which jurisdictions do the companies within the scope of the proposed integration operate?

- where are the taxes being paid?

- what are the tax attributes of the enlarged group?

- where are the tangible assets?

- where are the intangible assets?

- are there any non-core businesses or operations?

- what are the current transfer pricing policies?

1.3 Initial Assessment and Overall Integration Blueprint

It is then necessary to conduct a preliminary analysis of the information collected in order to develop an overall integration plan. The focus in this phase is on planning an integration that achieves the integration goals in the most efficient manner from a tax, cost and corporate perspective. The tax goal will often be to ensure that most or all of the steps in the integration are free from income and capital gains taxes in any jurisdiction, while minimizing any capital duty, local transfer and documentary taxes and avoiding any negative consequences on the business due to VAT and customs changes. The following tax goals also often come to bear:

- the integration of the corporate structure may be combined with a change in the inter- company commercial relationships of all or some of the combined group companies so as to minimize taxes globally;

- the acquired companies may have favorable tax attributes, such as net operating losses and unused foreign tax credits, and the integration should be conducted in a manner designed to preserve those attributes, where possible;

- the integration may be structured in a way to take advantage of existing tax attributes, such as using net operating losses in the acquired entities to offset taxable income in the existing structure;

- in the United States, there may be opportunities for domestic state and local tax minimization planning;

- there may be opportunities for minimizing other governmental costs (for example customs and VAT planning).

In the preliminary analysis phase, management and the outside advisors will consult with one another and develop a high-level integration plan. To the extent possible at this stage, the plan will specify which entities will be kept and which will be eliminated. It will also, where possible, specify the method of integration (for example “Target France Sarl will merge into Parent France Sarl,” or “Target UK Ltd. will sell all assets and all liabilities to Parent UK Ltd. and will then liquidate”). The overview document will be revised and expanded into a detailed steplist as the planning continues.

1.4 Preliminary Review of Integration Plan

Once the high-level integration plan has been developed, it is important to have the key constituencies (for example operations, tax, finance, legal, human resources, information systems) evaluate it and provide input on any issues the plan presents and any refinements that they wish to propose.

Depending on the scale of the integration project, this evaluation may take place in a single meeting or over several days or weeks.

It is important to note that developing the overall integration plan is often an iterative process because, as more information is learned about the entities to be consolidated, new issues and opportunities may present themselves and the integration goals may change. As the goals change, more fact gathering may be required. With each iteration, however, the integration goals become more refined and more detailed.

1.5 Comprehensive Steplist Plan Formulation

As the overall integration plan becomes more refined and is finalized, it should be expanded into a fully detailed list of each step necessary to execute the assigned tasks. The end product will be a complete plan and timetable for executing the assigned tasks with the names of those responsible for each step and, in the case of documents, the identity of the signatories. Interdependencies and steps that must follow a certain order or await permissions, filings and the like should be noted on the steplist.

1.6 Detailed Approval Process

As with the high-level integration plan, it is important to have the key constituencies evaluate the detailed steplist and provide input. Sometimes issues that were not apparent in the high-level plan become apparent when a person sees the detailed steps that will be taken and considers his or her role in implementing those steps.

1.7 Carrying out the Roadmap

There are various ways to manage the implementation of the detailed integration steplist. The specific approach will depend on the size of the project, the nature and geographical scope of the tasks involved and even the management styles and personalities of the individuals involved. The key to success in this phase is maintaining open and clear channels of communication about how the implementation is progressing, what issues are surfacing and making sure that there is a central decision maker available who can make executive decisions as and when required.

Throughout the execution phase the detailed integration steplist serves to track the status of tasks. Regular scheduled status calls with the key project individuals at the companies and the outside advisors keep the integration process on track, focusing minds on any open issues and allowing advisors and management to help identify what, if anything, is holding up completion of a particular step and take action accordingly.

2. Legal & Tax Considerations

Certain legal and tax considerations frequently arise in post-acquisition integrations. The discussion below is not intended to be exhaustive, particularly as additional issues, such as industry-specific considerations, can also apply.

2.1 Due Diligence Integration

As part of the information gathering phase of the plan, the company should undertake a legal and tax due diligence investigation of each of the entities involved (for example subsidiaries, branches, representative offices) in order to identify legal and tax issues that need to be dealt with before or during the consolidation. This investigation should not just delve into the acquired entities, but also into the existing entities with which they will be consolidated. Experienced legal counsel should be able to provide a due diligence checklist, which would include such items as determining what assets the entities own, identifying contracts that may need to be assigned, identifying ongoing litigation, tax attributes, data protection issues, employment matters etc. (see Section 4 for a sample checklist).

Opportunities for starting the integration due diligence process before the acquisition is complete (i.e., during the acquisition due diligence itself) are often overlooked. After an acquisition completes, it typically becomes increasingly difficult to gather the information and documentation needed to conduct an effective and efficient integration. As time passes, people who worked for the acquired companies often depart, taking institutional knowledge with them, and those who remain are often not as highly motivated for the task of gathering required documents and facts as they were during the pre-acquisition phase. Furthermore, leveraging the often considerable resources marshalled for the acquisition due diligence to also address consolidation due diligence issues can be much more cost effective than starting a new due diligence process after the deal closes. However, when planning commences before completion of the acquisition of a competitor, attention must be paid to antitrust restrictions on the sharing of information. See Section 8 for more detail.

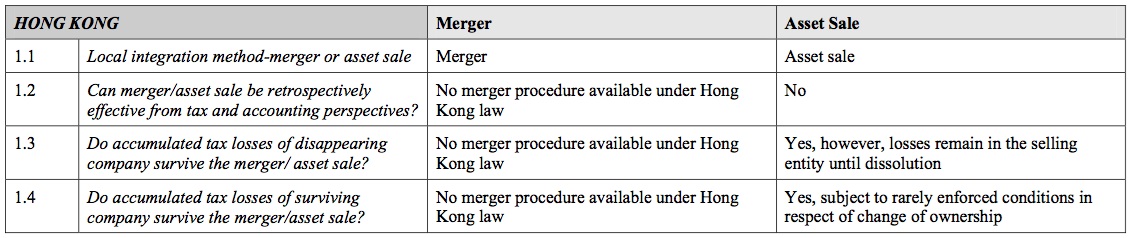

2.2 Choosing Between Local Statutory Mergers and Asset Transfers

In many jurisdictions, the local corporate laws provide for statutory mergers. In these jurisdictions, the alternative approaches of merger vs. sale-and-liquidation should be compared to see which one best achieves the integration goals. Statutory mergers are often advantageous because it is then generally the case that the assets and contracts of the non-surviving entity transfer automatically, whereas individual transfers of assets and contracts can be cumbersome, for example there may be a requirement to register any change of ownership of assets and, in certain cases, a third party or a government must approve the transfer of an asset or contract. In these situations, a merger may effectively be the only means to transfer certain assets. Local merger regimes often also have tax benefits. Indeed, even if the only benefit of the local statutory merger regime is that the transaction is tax-free for local tax purposes, this benefit can be substantial.

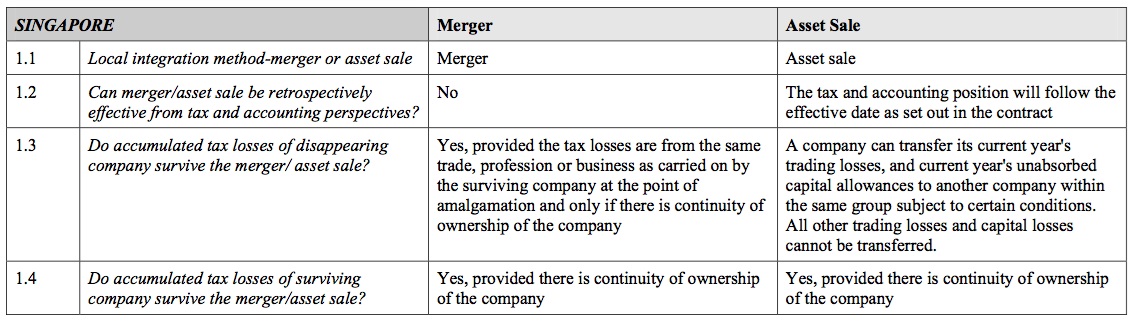

Some jurisdictions have recently introduced merger legislation; one such jurisdiction is Singapore, where a change to the Singapore Companies Act in 2006 means that two or more Singapore incorporated companies can now be amalgamated.

A number of jurisdictions simply do not have a merger statute that allows local companies to merge together. In these jurisdictions, the only choice available for combining two companies may be some variation on the theme of selling (or otherwise transferring) the assets of one company to the other and then liquidating or dissolving the seller entity. These jurisdictions tend to be common law countries such as Hong Kong and the UK. These jurisdictions often allow for a business transfer within a local group to occur without taxable gain, and achieve the objective of consolidating the two local businesses in a manner that is functionally equivalent to a merger from a local perspective.

Moreover, a business transfer can usually be converted into a tax-free reorganization from a US tax perspective. If a business transfer or merger is not possible or desirable, two further ways in which the businesses can be “integrated” are by utilizing local tax consolidation/group rules or by having one company operate the other’s business under a management contract, or business lease, during the interim period. These options do not result in full integration with a single entity in the jurisdiction, and further details are set out in paragraph 3.3 of Section 3 “Tax Considerations”.

2.3 Asset Relocation Strategies

Where the local integration method chosen requires the individual transfer of assets, steps must be taken to effect the transfer, and sometimes registration, of the legal ownership of the assets. The steps required will depend on the type of assets involved. In many cases, a simple asset sale and purchase agreement will suffice to transfer title.

In the case of some assets, however, such as real property, automobiles or certain types of intellectual property, the change in legal title may have to be recorded with governmental or regulatory authorities to be effective. Moreover, in some cases approval of a governmental agency must be obtained before transfer of governmental licenses, permits, approvals and rulings.

In certain jurisdictions, even a general asset transfer agreement may have to be filed with local authorities and may have to be drafted in a local language. Bulk sales laws may apply to significant asset transactions with the effect that liabilities and creditors’ rights transfer by operation of law with the assets. Local insolvency and creditor protection laws need to be taken into consideration (for example those prohibiting transactions at an undervalue) especially when there is a plan to wind up the transferor entity. In addition, the asset transfer may give rise to issues of corporate benefit and directors’ statutory or fiduciary duties. Also, separate formalities are almost always required to effect the transfer of shares of subsidiaries.

A key issue in asset transfer jurisdictions is ascertaining the purchase price to be paid for the assets to be transferred. Often the interests from tax, corporate law, accounting and treasury perspectives will compete. For example, a sale by a subsidiary to its parent at less than market value may be an unlawful return of capital to the shareholder. However, a sale at market value may result in significant goodwill being recognized by the parent company for local statutory accounting purposes. Depending on the group’s or local entity’s goodwill amortisation policy, a “dividend blocker” could be created at the level of the parent, as the amortisation created by the acquisition is expensed through the parent’s profit and loss account.

2.4 Contract Novation and Assignment Methods

In a local asset sale or merger, existing contracts, such as office leases, equipment leases, service agreements, distributor agreements, customer agreements, supplier agreements, utility and telephone accounts, and a host of other operational agreements, will have to be transferred to the surviving entity.

In a merger, these assignments almost always occur by operation of law, but in other cases steps have to be taken to effect the novation or assignment (see Section 10 for a summary by jurisdiction). These steps may range from giving a simple notice of assignment to all third parties to obtaining written consent from the other party to permit the novation (by way of a tripartite contract) of all of the rights and obligations to the surviving entity.

It may be prudent, though not practically desirable, to review contracts, particularly key arrangements, in order to determine whether they are freely transferable or whether permission is required. Even in a merger between affiliates it may be advisable to review the contracts of both affiliates to determine whether their contracts contain any provisions that may be triggered by the merger, such as provisions giving the other party the right to terminate upon a merger or change in control.

If the surviving and disappearing entity use different suppliers for the same product or raw material and it is intended to rationalize the supply chain, it will be necessary to identify the likely cost of cancelling those supply contracts which are not to be continued or whether the third party has the bargaining power to impose new contractual terms which comprise of the best of both pre-existing arrangements.

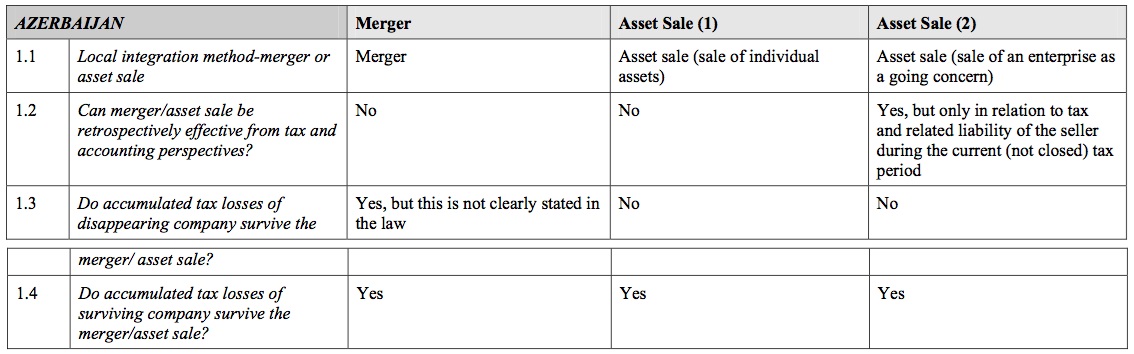

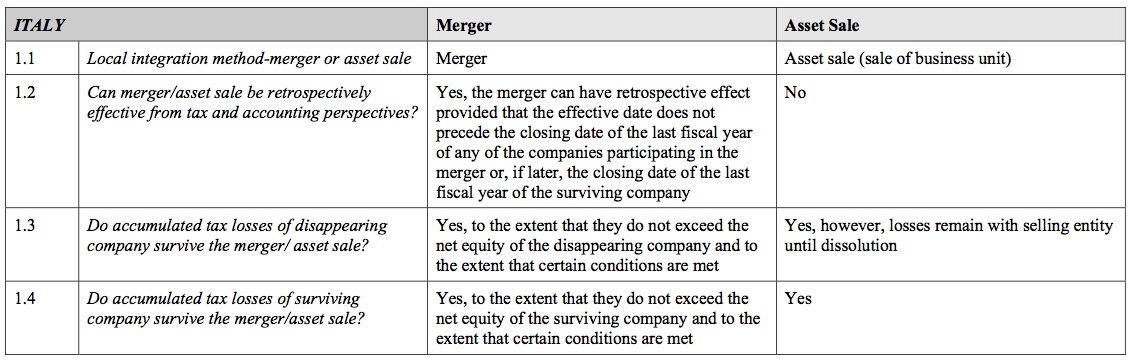

2.5 Tax Attribute Preservation Strategies

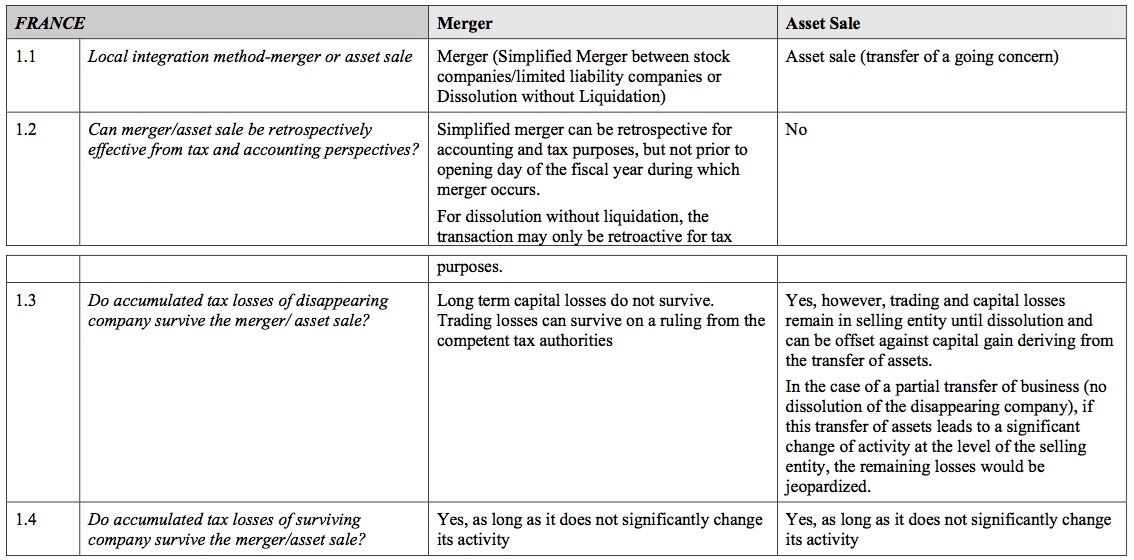

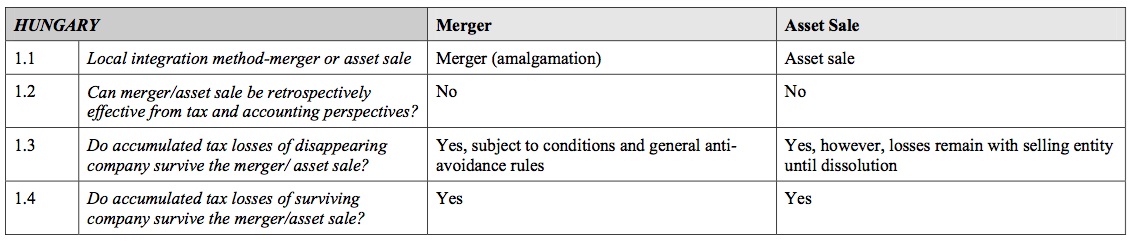

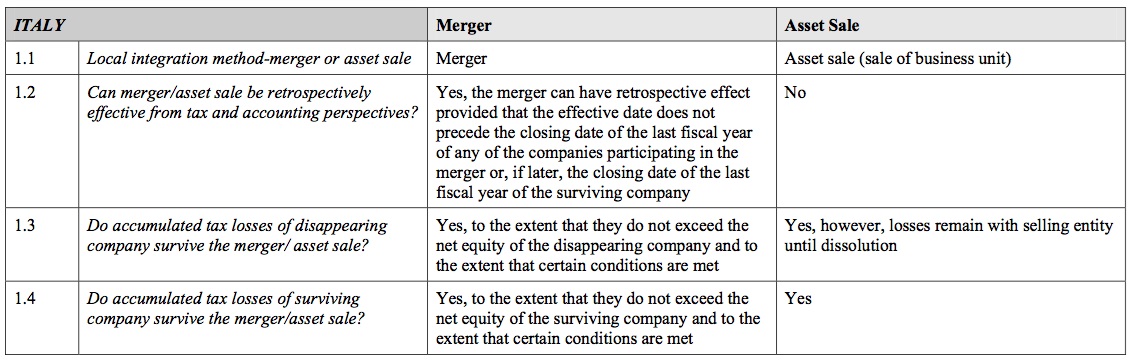

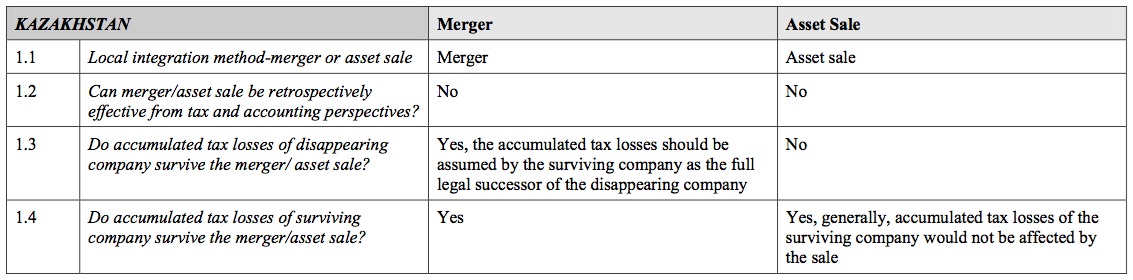

Favorable local tax attributes, such as net operating losses or current year or carried forward tax losses (Net Operating Losses, “NOLs”), can provide a permanent benefit to the company if preserved. In many jurisdictions, how a consolidation is executed will have an impact on whether the NOLs survive.

For instance, in some jurisdictions, the NOLs of the acquiring or surviving subsidiary are preserved, but the NOLs of the target or absorbed company are restricted (for example Italy) or lost (for example many Latin American countries). Thus, it may be beneficial to make the company with the NOLs the surviving company in the consolidation. Similarly, in many jurisdictions, transferring the shares of a subsidiary may impact the survival of the NOLs (for example Germany). In such a case, it may be beneficial to merge the profitable company into the loss-making company (rather than vice versa).

In other cases, a cash or asset infusion can impact the NOLs. In fact, in many countries, a mere change in the business may be sufficient to restrict or eliminate the NOLs (for example the UK and Australia). Finally, in many countries it may be advisable, or even necessary, to obtain an advance ruling with respect to the NOLs to confirm that the NOLs (or at least some portion of them) will survive the local consolidation (for example France).

In a merger, these assignments almost always occur by operation of law, but in other cases steps have to be taken to effect the novation or assignment (see Section 10 for a summary by jurisdiction). These steps may range from giving a simple notice of assignment to all third parties to obtaining written consent from the other party to permit the novation (by way of a tripartite contract) of all of the rights and obligations to the surviving entity.

It may be prudent, though not practically desirable, to review contracts, particularly key arrangements, in order to determine whether they are freely transferable or whether permission is required. Even in a merger between affiliates it may be advisable to review the contracts of both affiliates to determine whether their contracts contain any provisions that may be triggered by the merger, such as provisions giving the other party the right to terminate upon a merger or change in control.

If the surviving and disappearing entity use different suppliers for the same product or raw material and it is intended to rationalize the supply chain, it will be necessary to identify the likely cost of cancelling those supply contracts which are not to be continued or whether the third party has the bargaining power to impose new contractual terms which comprise of the best of both pre-existing arrangements.

2.6 Tax Efficiency Measures for Corporations and Shareholders

In the transactions undertaken to integrate the acquired entities, it is important to avoid, or at least minimize, foreign income taxes. Foreign income taxes can be imposed on the consolidating corporations with respect to their assets. Similarly, income taxes can be imposed on the shareholders in connection with stock transfers.

If structured properly, foreign corporate level income taxes can often be avoided either by consolidating through a merger, if available, or through the local form of consolidation or group relief. Stock transfers, on the other hand, may be exempt from income tax due to either the appropriate double tax treaty, an EU Directive, or local law.

2.7 Navigating Transfer, Stamp, and Real Estate Taxes

Many countries have stock transfer or stamp taxes (for example Taiwan at 0.3%). Although such taxes may not be great, they are a real out-of-pocket cost to the company. For the same reason, foreign capital taxes and documentary taxes should be avoided whenever possible. Thus, where possible, steps should be taken to avoid or minimize these taxes, and exemptions will often be available for intra-group transactions. Some countries, such as Austria, tax the transfer of real estate where the entire issued share capital of a company is transferred which can result in tax arising both on share transfer and the subsequent merger.

2.8 Addressing Severance and Restructuring Charges

Most integrations result in some severance or other restructuring costs. In most jurisdictions, provided that appropriate precautions are taken, these costs are deductible for local income tax purposes. There is nevertheless often a number of strategic considerations that should be taken into account when deciding when and how to incur restructuring costs such as those arising from the elimination of employees. Domestic and foreign tax consequences are among these strategic considerations.

2.9 Strategies for Foreign Tax Planning

A variety of foreign tax planning opportunities may arise in connection with any international integration. For instance, in many jurisdictions there will be an opportunity to obtain a tax basis increase or “step up” in the assets of the local company transferring its assets, sometimes without any local tax cost. It may be possible to leverage the surviving company with additional debt in connection with the integration. The interest deductions can then be used to erode or reduce the local tax base. In addition, if the parent is the lender, the repayments of principal can generally be used to repatriate earnings without both income tax and withholding tax.

2.10 Pre-Integration Share Ownership Structure

It is generally preferable to create a share ownership structure where the shares of the foreign subsidiaries are in a direct parent/subsidiary or brother/sister relationship with the entity with which they will be integrated, since many jurisdictions, such as the state of Delaware or Germany, have short-form merger procedures which are easier and cheaper to implement if such a structure is in place.

A further benefit to a parent/subsidiary or brother/sister relationship being established for the integration is that, following the merger, the surviving subsidiary will have a single shareholder, making future distributions, redemptions and restructurings easier to implement.

If the subsidiaries are not in a parent/subsidiary or brother/sister relationship prior to the merger, usually each shareholder must receive its pro-rata portion of the shares in the consolidated entity. This requirement creates practical and timing issues as comparable financial information will be required for the merging entities.

A number of methods can be used to achieve a parent/subsidiary or brother/sister relationship prior to an integration, including:

- the acquiring company contributing its foreign subsidiaries downstream to the target company;

- the target company distributing its subsidiaries upstream to the acquiring company;

- the shares of the subsidiaries being sold within the

The most common method is a transfer by the acquiring company of its subsidiaries downstream to a lower tier target company and various issues, including tax, must be considered. One corporate law consideration is whether the company which is receiving a contribution which consists of shares in another company has to issue new shares for local company law purposes.

Another consideration which may affect how the group is restructured will depend on the ultimate destination of the company being transferred. If this destination is several tiers down, transferring through each of the shareholding tiers may create considerable work. A direct contribution to the ultimate destination will invariably involve the issue of new shares by the company receiving the contribution.

In some situations this is undesirable since it can complicate the group structure; in other situations it can be an advantage. For example, a direct shareholding by a parent company in a lower tier subsidiary may give rise to a more tax efficient dividend flow, or may enable the parent company to access profits of a subsidiary that previously have been “blocked” by an intermediate subsidiary company which is unable to declare and pay dividends because of an earnings deficit on its balance sheet.

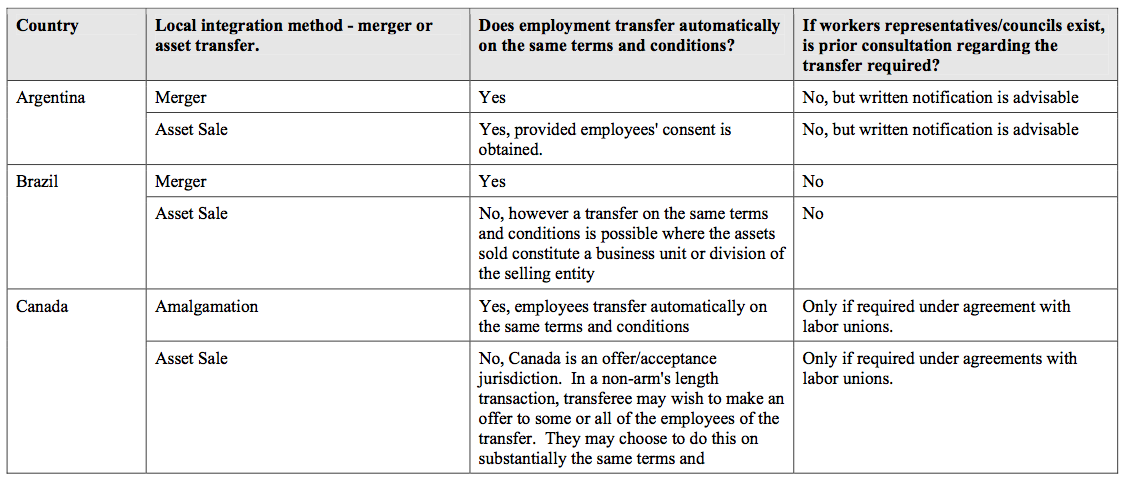

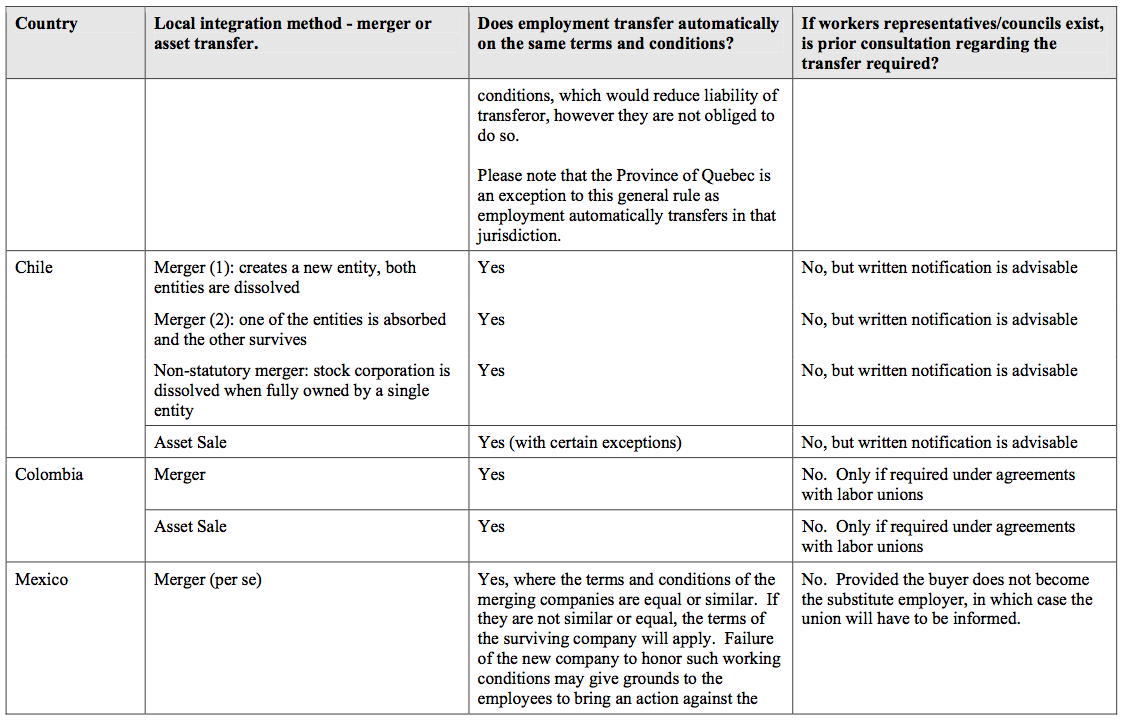

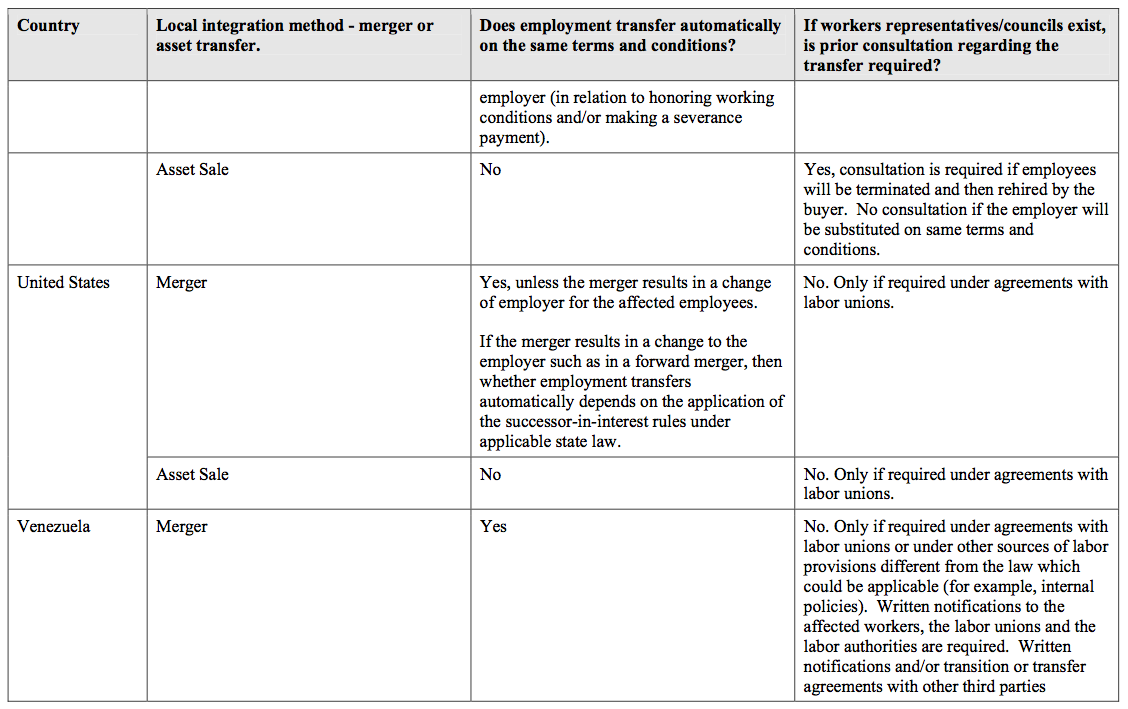

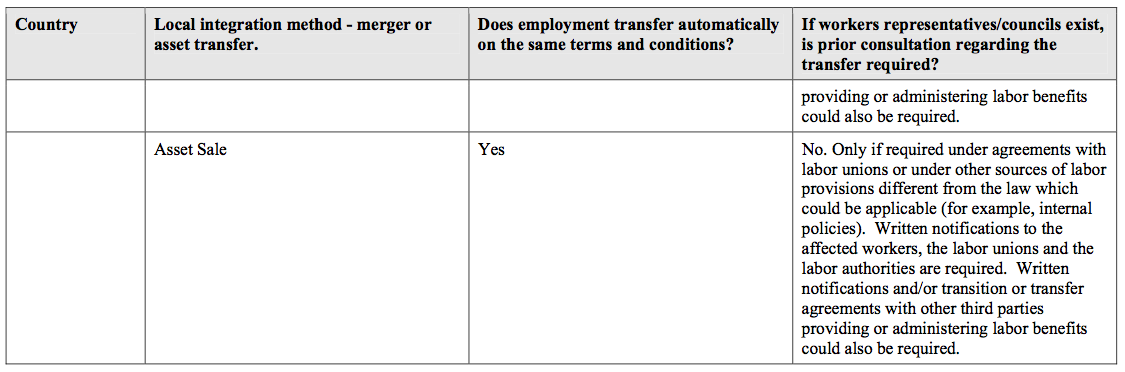

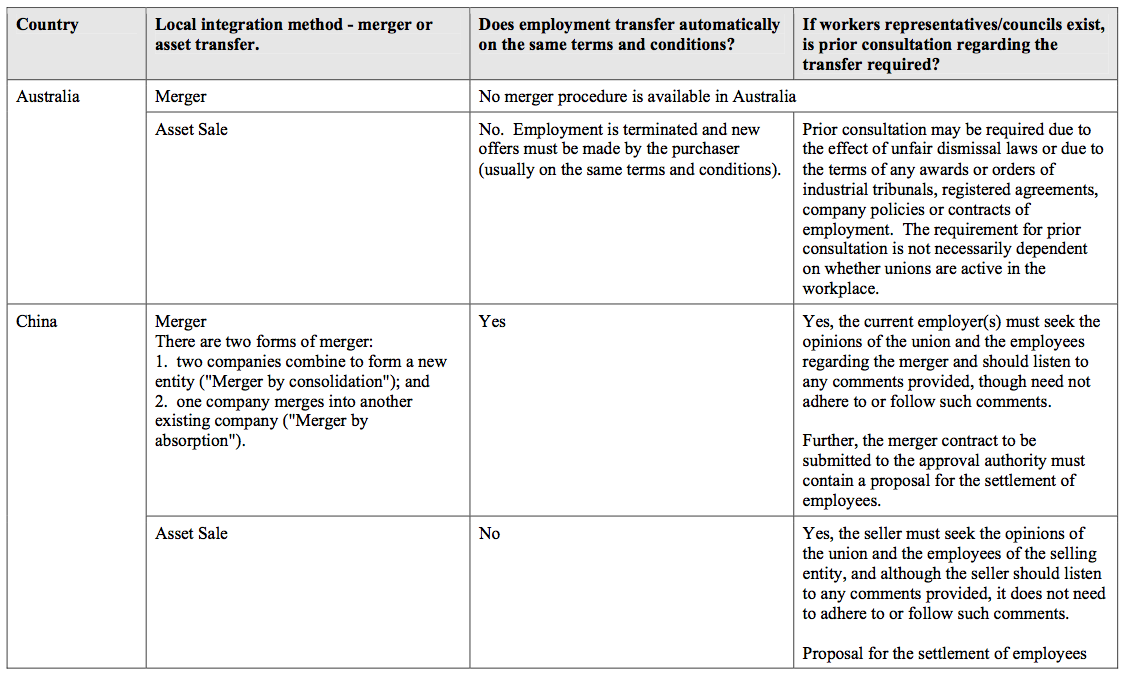

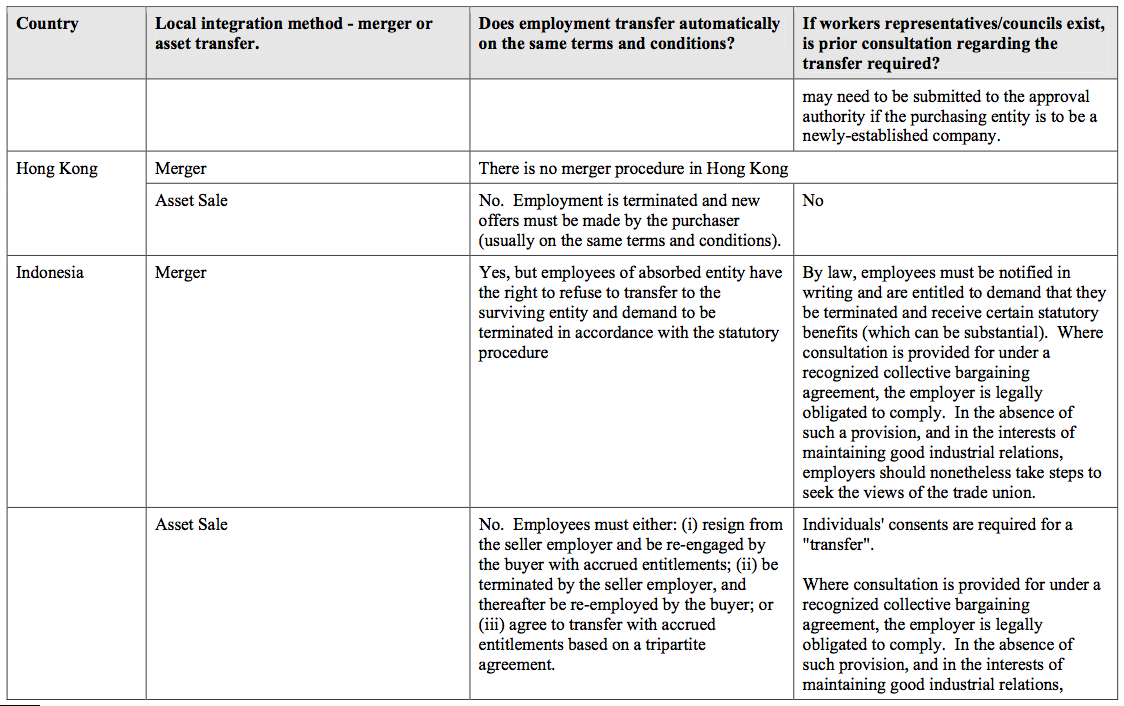

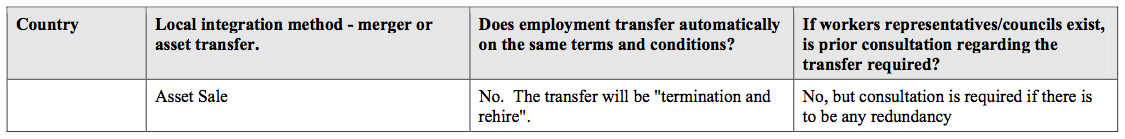

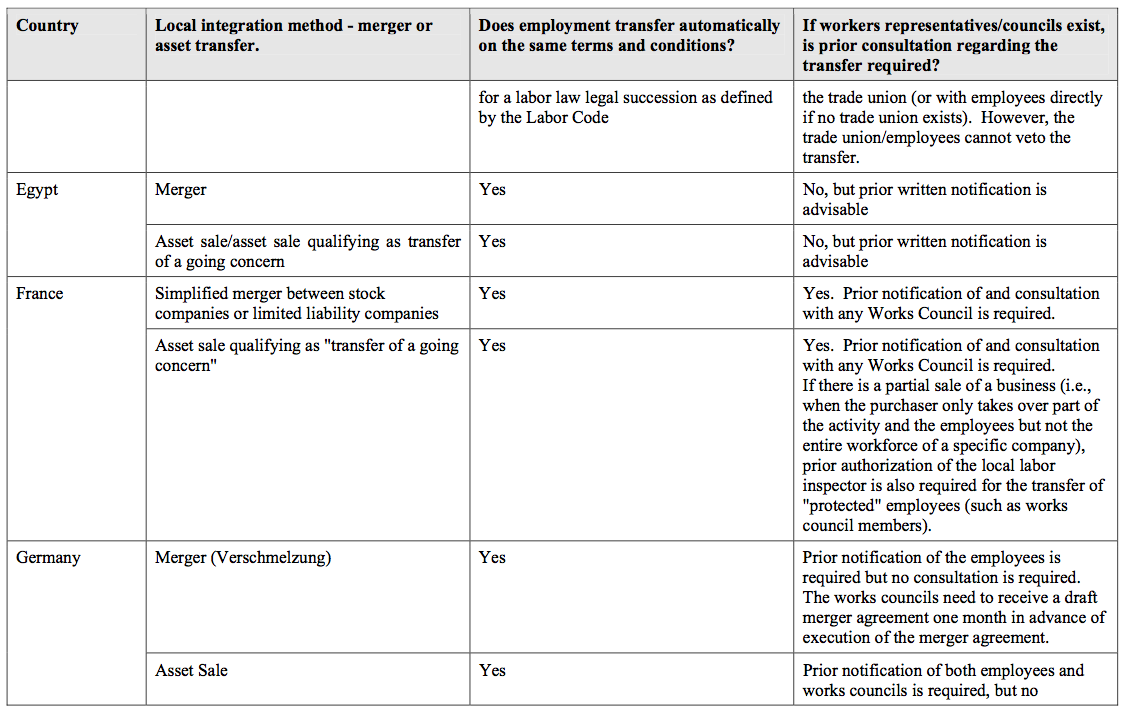

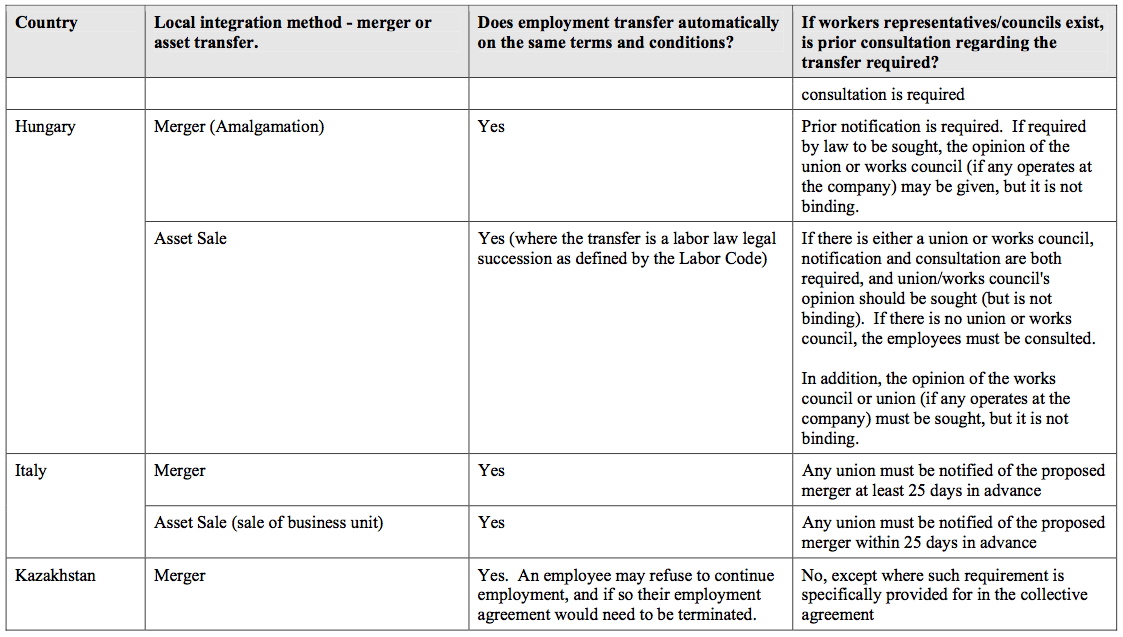

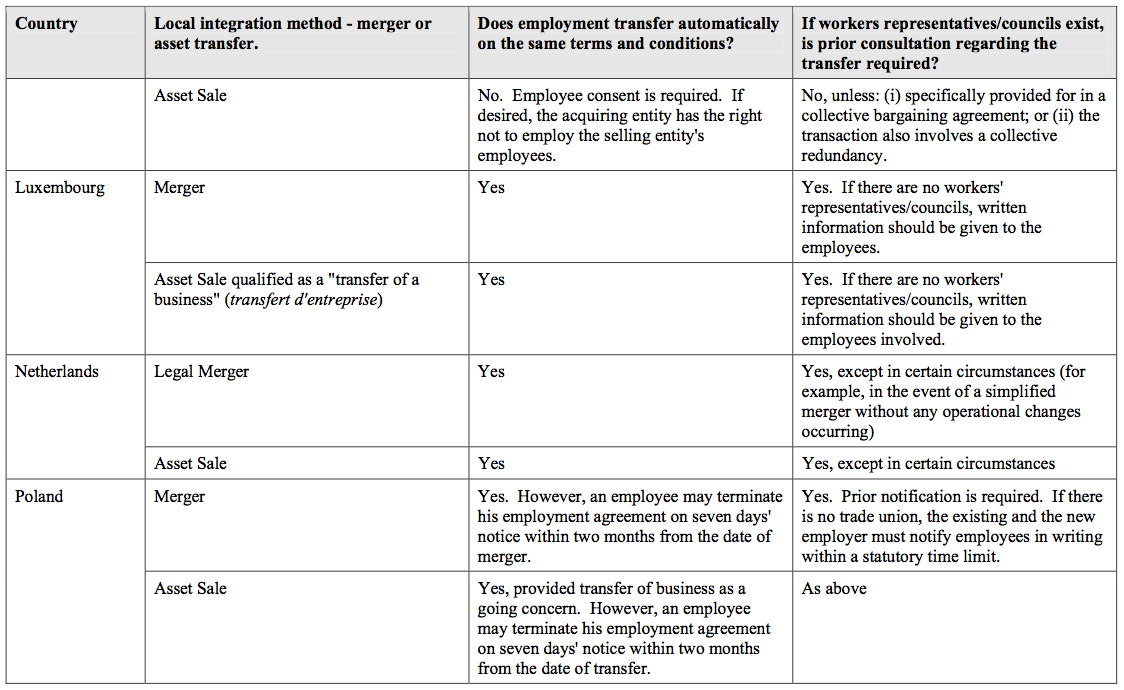

2.11 Legal Factors in Employment

Where the integration involves an asset transfer, it will normally be necessary to take some additional steps to transfer employees. Commonly this will be by termination and rehire, but in some jurisdictions, mainly in the EU, the employees may transfer automatically by law. In a merger or asset transfer (and very occasionally on a share transfer) there may also be obligations to inform and potentially consult with employee representatives such as works councils or trade unions.

In some cases, those bodies have a right not only to be informed and consulted but also to deliver an opinion on the plans for the local integration before they are finalized and implemented, and it may be a significant violation of local law to make changes in the management of the local company or undertake an integration transaction without formally consulting with them. Due diligence should therefore obtain details of all employee representatives, unions etc. and input as to the employee relationship environment in each country, as time for information and consultation should be built into the step plan.

One of the common objectives of a business acquisition followed by an integration is that duplicate functions can be eliminated, thereby streamlining the operation of the combined businesses. In addition, there is often a desire to harmonize the compensation packages, benefits, and working conditions of the workforce.

In many jurisdictions, workers have significant protection from changes to working conditions, benefits and dismissal. In those countries, if an employer changes an employee’s working conditions or terminates an employee in connection with an acquisition and the subsequent local integration, the employee can be entitled to compensation or reinstatement. It may even be the case that changes to employment terms are simply ineffective, allowing the employees to demand the old terms at any time.

2.12 Changes in Executive Leadership

In the aftermath of an acquisition, some of the executives of the target company, and possibly also of the acquiring company, may leave. If these individuals are serving as officers or directors of local subsidiaries, they must be replaced so that it is possible to continue to take corporate actions at the subsidiary level to effect the integration. A similar issue arises with respect to individual employees who are serving as nominee shareholders to satisfy minimum shareholder or resident shareholder requirements in a particular jurisdiction. If these individuals have left employment with the company, they may have to be tracked down to sign share transfer or other documents.

2.13 Minimizing Delays and Notices

In many jurisdictions, government or tax clearances are required prior to the merger or liquidation of the local entities. Even in jurisdictions where government clearances are not required, public notices are often necessary and statutory waiting periods often apply. These formalities can delay the integration. Accordingly, it is important to identify the jurisdictions where immediate integration is desired so that the required applications and notices can be filed as soon as possible.

In cases where there are statutory or practical delays in implementing the integration, alternative strategies may be available for dealing with the delays to minimize operational inconvenience or tax exposure, including:

- having one company operate the other’s business under a management contract during the interim period;

- selling the business to the surviving company, with a subsequent merger to eliminate the empty company; and

- making the merger retroactive for tax and/or accounting purposes under local law.

In any case where the delay is significant or there is a strategic objective to have the local businesses integrate on a particular date, for example, these alternatives should be explored.

2.14 Required Corporate Compliance Processes

The due diligence exercise may highlight deficiencies with the corporate compliance status of the group and so it may be necessary to take corrective action before integration can be started or concluded. For example, if acquired subsidiaries are technically insolvent or have not complied with their annual corporate filing or other maintenance requirements, it will typically be necessary to correct these deficiencies before any significant integration steps, such as mergers or liquidations, can be undertaken.

Integrations are frequently delayed because the entities that are to be eliminated have not been properly maintained and there is a need to create statutory accounts, hold remedial annual meetings and make the necessary delinquent tax and corporate filings. These problems can be compounded if local company directors have left, and it can be difficult to persuade management to serve on the boards of local subsidiaries that are not in compliance with their obligations. Further details are set out in Section 8 Compliance and Risk Management.

2.15 Management of Branches & Subsidiaries

It is important not to overlook any branches, representative offices and other business registrations of entities that are disappearing in the integration. In many cases, it would be a mistake simply to merge one subsidiary into another on the assumption that any branches of the disappearing entity will automatically become branches of the merged entity. Many government authorities view a branch as being a branch of a specific entity and, if that entity disappears in a merger, the survivor will have to register a new branch to account for its assets and activities in the jurisdiction.

In some cases, merging an entity before de-registering its branch or representative office can cause great difficulties with the authorities in the jurisdiction where the branch was registered, as these authorities will treat the branch as continuing to exist, and continuing to have ongoing filing and other obligations, until it is formally de-registered. Furthermore, the process of de-registration may be greatly hindered or may be technically impossible if the entity no longer exists.

Similar complications can ensue if it is assumed that shares of subsidiaries will automatically transfer when the original parent company is merged into another group company. Effecting the local legal transfer of the shares of the subsidiaries can be problematic if not identified and planned in advance.

2.16 Authority for Corporate Approvals

Integrations typically involve extraordinary or non-routine transactions (for example the sale of all of a subsidiary’s assets to an affiliate). The individual directors or officers of the entities involved may not have the necessary corporate authority to effect those transactions. Therefore, it is often necessary to consult applicable local law and the articles of association or other constitutional documents of the entities involved to determine if there are any corporate restrictions on the proposed transactions, and then to take appropriate steps to authorize the transactions, such as adopting board resolutions, shareholder resolutions or amending the constitutional documents. Thorough documentation recording corporate decisions assists in memorializing the background to decisions and can be helpful where the transactions are reviewed as part of accounting or tax audits.

SECTION 3: TAX MATTERS

1. Introduction

1.1 Tax Planning Goals

When planning a post-acquisition integration project it is imperative that management and their advisors consider the tax issues at an early stage to determine the type and magnitude of tax risks and identify tax planning opportunities. Management and the advisors should consider at an early stage how tax planning goals will be balanced with business factors when developing a plan for the structure of the integration.

Many factors influence the tax structuring options available when planning an integration, for example: the existing tax attributes of the companies; tax planning already undertaken; the future strategic plans for the new group; anticipated changes in the local and global tax environment; the tax audit profile of the companies; planned flotations, spin-offs and further acquisitions.

In some situations, management may wish to actively take advantage of tax planning opportunities the integration may create in order to enhance the after tax cash flow. It may, for example, be the stated intention of management to reorganize the shareholding structure of the group to allow for tax efficient repatriation of earnings in foreign subsidiaries to the parent company, to create a global group cash management function, or to minimize the group’s global effective tax rate. In terms of the latter goal, post-acquisition tax planning will, first and foremost, seek to convert and allocate the purchase consideration to tax amortisable asset capitalisation. The second priority will be to push down any leverage incurred in financing the purchase consideration to local entities and thereby reduce their pre- tax earnings.

For planning purposes it is normally straightforward to assess the tax costs of achieving the business objectives of the integration. Tax costs (or tax planning savings) are treated like any other business cost (or benefit) and form part of the cost/benefit analysis that management undertakes when formulating the integration plans.

One difficulty usually experienced by management during the early stage of an integration project is putting a number on the expected tax costs or expected tax planning benefits. It may not be until the fine details of the integration plans are settled that tax issues and costs can be accurately identified. An unexpected tax cost to an integration can be a bitter pill to swallow and emphasizes the need for careful and detailed planning, not only at a local level, but also with a view to global issues.

1.2 Valuable Tax Attributes

In many cases either one or both local subsidiaries may have valuable tax attributes, such as accumulated tax losses (NOLs). Preserving these tax attributes is likely to be an important goal of any integration project. However, it will always be important to weigh the value of tax attributes (taking into account projected profitability of the integrated business and loss expiry rules) against the business costs of preserving the losses. In some jurisdictions, for example, a business lease between the two operating subsidiaries may have advantages over a merger from an NOL preservation perspective, but the lease can be a more difficult structure from an ongoing accounting and business perspective. Which structure is chosen will also depend on the relative value of preserving tax attributes as against the cost of implementing a more cumbersome integration structure.

Where preservation of tax attributes is an important goal, invariably local tax laws contain anti- avoidance legislation which can limit the transfer of the existing NOLs from one group company to another or their use within a group of companies. In the context of a post-acquisition integration project, the operation of these rules must be examined in three circumstances.

First, the original acquisition of the target group by the acquiring group may mean that the existing NOLs have already been lost, are restricted in some way, or cannot be used against profits of the acquiring or a surviving company in the same jurisdiction. In the UK, for example, where a change in the ultimate shareholder of a UK company coincides within three years with a major change in the business of the company, NOLs can be cancelled.

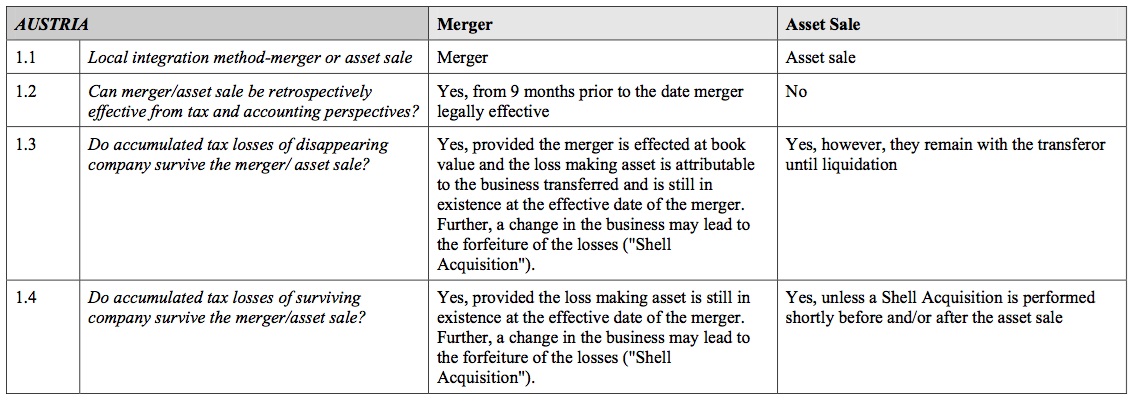

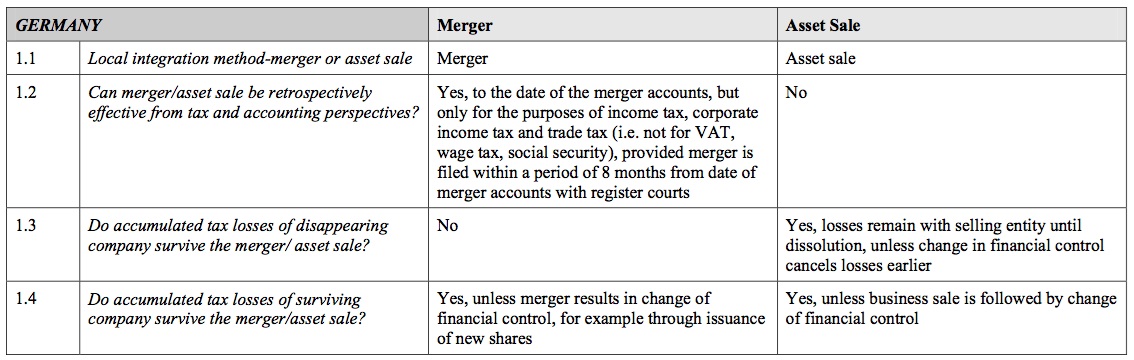

Second, in some jurisdictions share-prepositioning steps can have an impact on tax attributes. In Germany, for example, the transfer of a direct or indirect interest in a German company can (absent a specific relief or exemption) result in the carry forward of NOLs being restricted, or even prohibited. This means that share transfers a long way up the ownership chain that do not involve any German companies directly can impact on the preservation of tax attributes in the German companies. It is therefore crucial, in planning a reorganization, to consider the impact of each step on the integration plan in every jurisdiction. Austria is a good example of a country which preserves losses in most acquisition and integration situations.

Third, in many jurisdictions the manner in which the asset transfer is executed will have an impact on whether the NOLs survive. For instance, in many jurisdictions, the NOLs of the acquiring subsidiary are preserved, but the NOLs of the selling company are restricted. Thus, it may be beneficial to make the company with the NOLs the buying company in the integration. In fact, in many countries, a mere change in the business may be sufficient to restrict or eliminate the NOLs (for example the UK and Australia).

One final point to note in this area is that it is often possible to obtain a binding advance ruling from the relevant tax authority confirming that NOLs will be unaffected by the integration steps (or, where relevant, carry over into the integrated entity. Indeed, in some jurisdictions and circumstances, obtaining a pre-transaction ruling is a prerequisite for NOLs to survive.

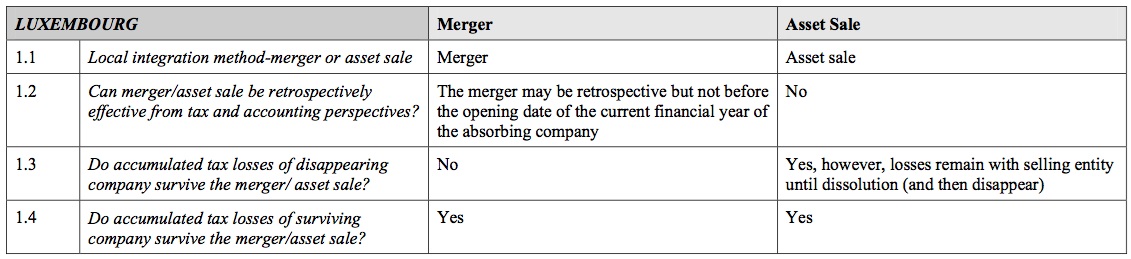

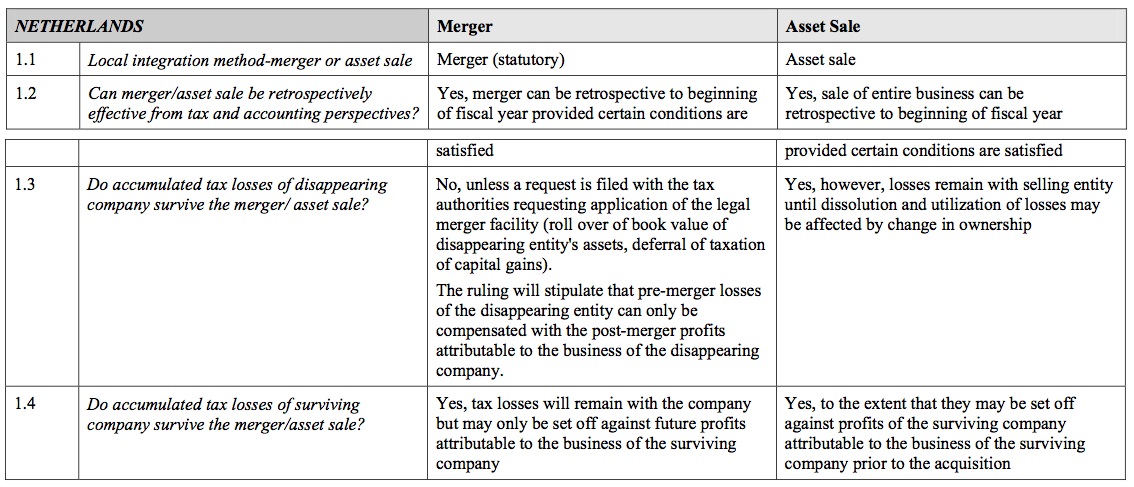

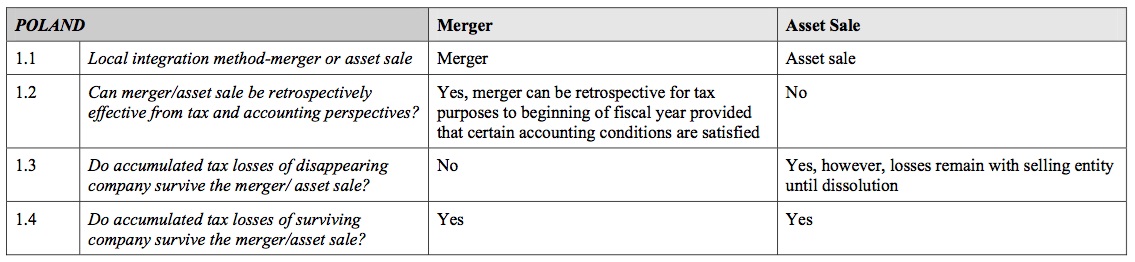

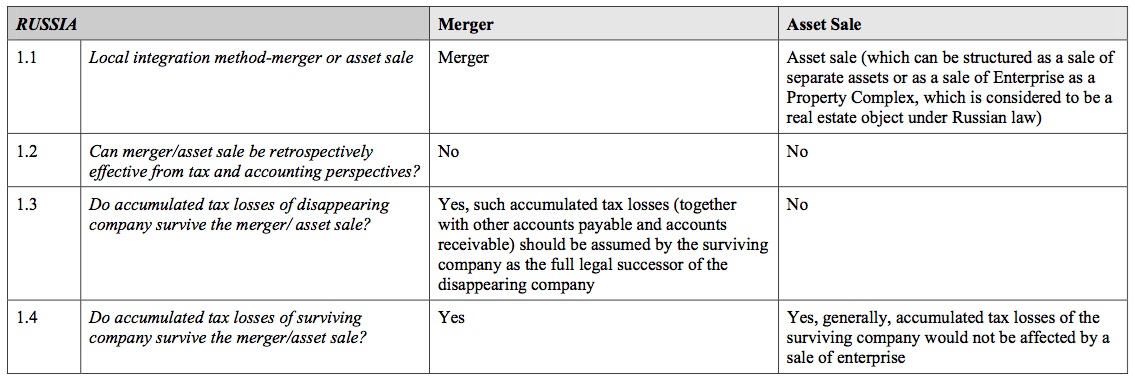

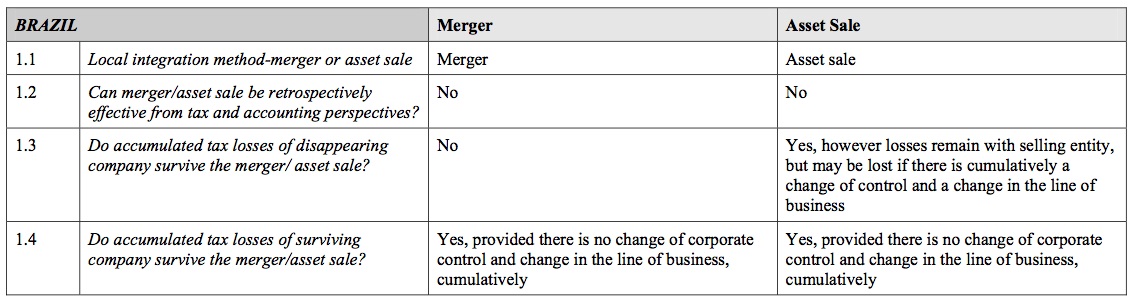

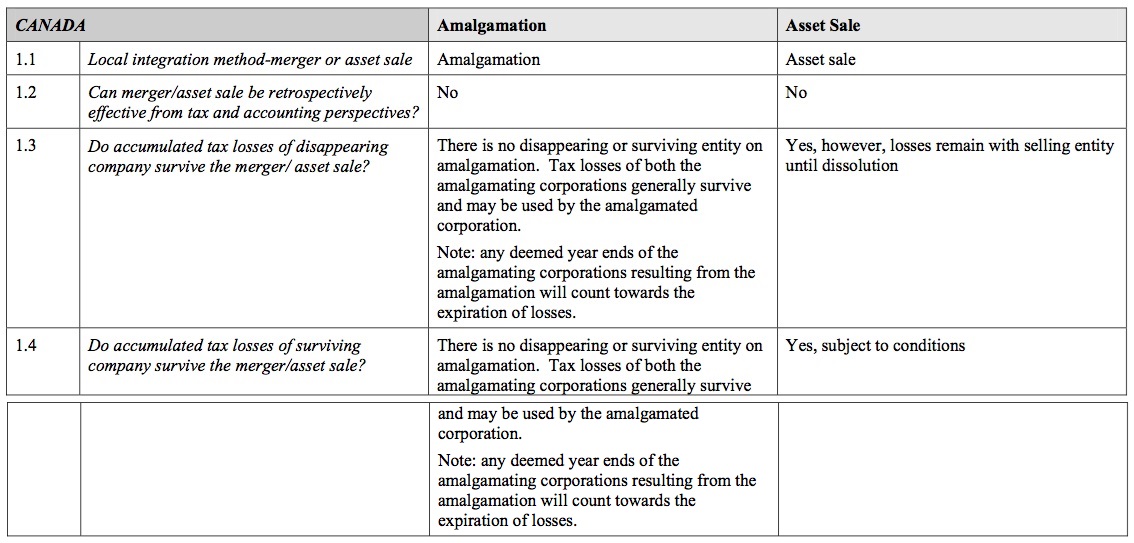

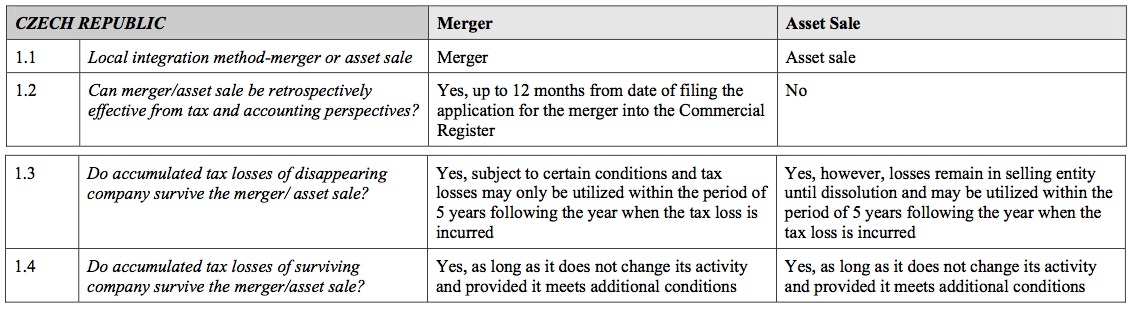

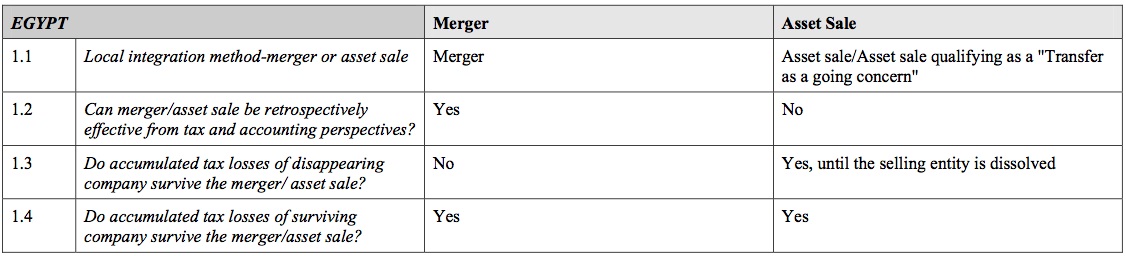

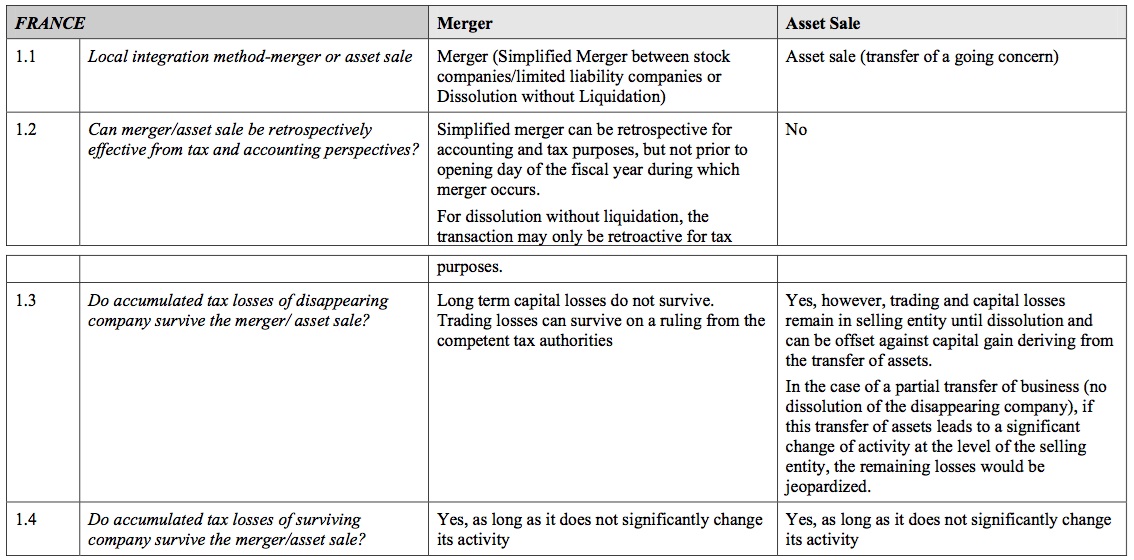

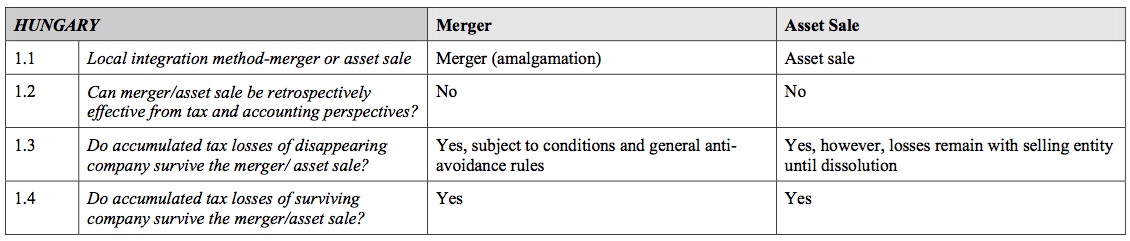

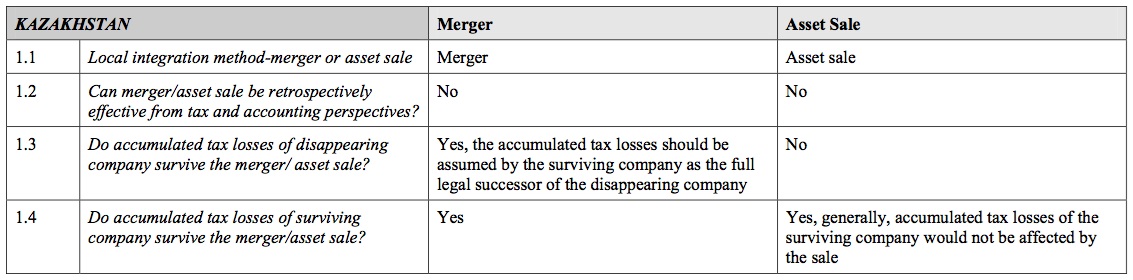

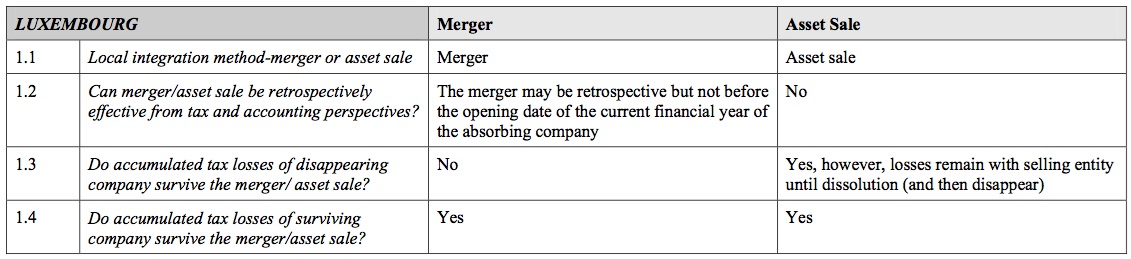

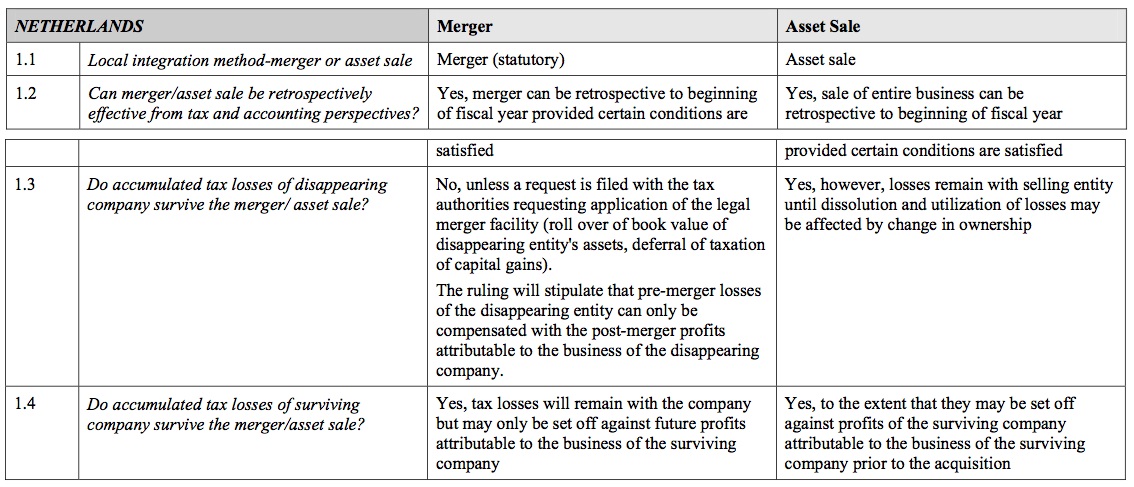

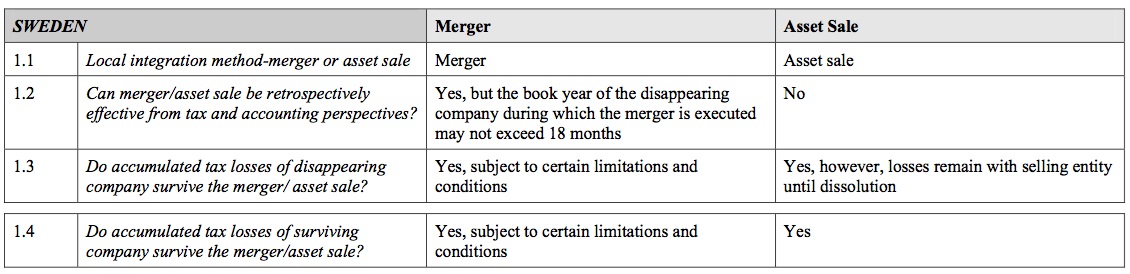

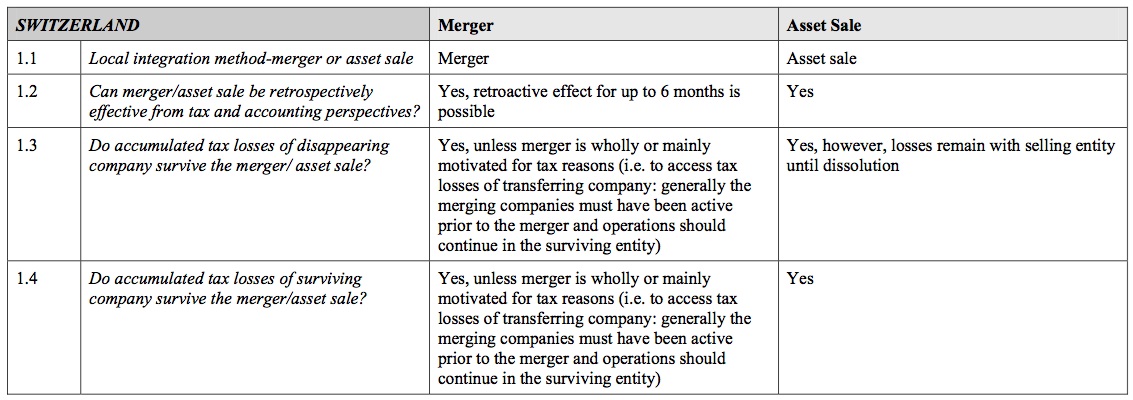

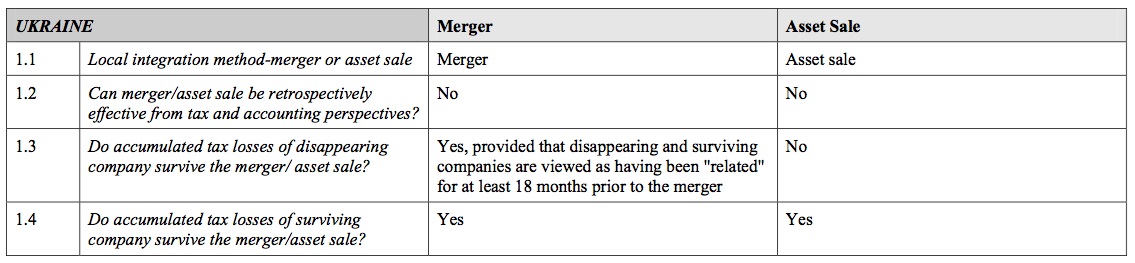

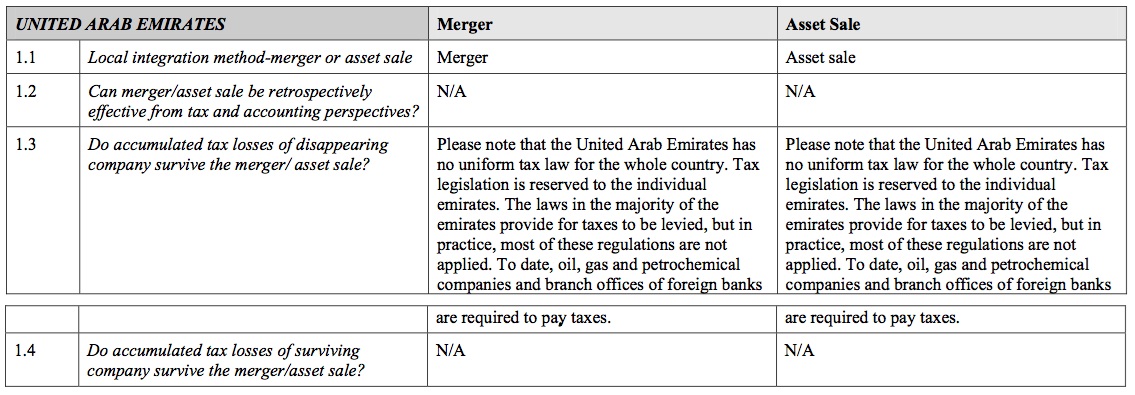

The treatment of NOLs in various jurisdictions is summarized at the end of this section.

2. Creation of Branches & Subsidiaries

As explained in more detail in paragraph 2.10 of Section 2, there are a number of advantages to achieving a parent/subsidiary or brother/sister subsidiary relationship prior to an integration. The methods to achieve this relationship include:

- the acquiring company contributing its foreign subsidiaries downstream to the target company;

- the target company distributing its subsidiaries upstream to the acquiring company; or

- the shares of the subsidiaries being sold within the organisation

2.1 Downstream Contributions

The immediate tax consequences of downstream contributions must be considered at three levels. The first level is the tax treatment in the home jurisdiction of the company making the contribution. In many jurisdictions, which include traditional holding company jurisdictions such as Luxembourg and the Netherlands, participation exemptions should allow such contributions to be made tax-free. In other jurisdictions the contribution may have to be structured as a tax-free reorganization either because the jurisdiction does not have a participation exemption or the participation exemption does not apply, where, for example, a qualifying holding period has not been satisfied – which can often be the case in post-acquisition integration projects. Such a tax-free reorganization would usually involve the issue of shares by the company which is receiving the contribution

The next level to consider is the tax treatment for the company receiving the contribution; i.e., is the receipt of the contribution a taxable event? For example, a contribution to a Japanese company without the issue of shares gives rise to a taxable receipt for the Japanese company equal to the fair market value of the shares contributed. In other jurisdictions, for example Switzerland, the contribution may be subject to capital duty.

The third level to be considered from a tax perspective is the tax treatment in the jurisdiction of incorporation of the company being contributed. Is the transfer of legal ownership in the contributed company subject to local transfer taxes, notarial fees and/or registration fees? Does that jurisdiction seek to levy tax on a non-resident shareholder disposing of shares in a company incorporated in that jurisdiction? The taxing rights of the local jurisdiction may be limited under double tax treaties entered into with the jurisdiction in which the company making the contribution is resident, but this is not always the case. Mexico, for example, taxes non-resident shareholders disposing of shares in Mexican companies, and the Mexico-Germany tax treaty allows the Mexican tax authorities to tax gains arising on a disposal of Mexican shares by a German company. Subject to limited exemptions, China, similarly, taxes non-resident shareholders on the disposal of shares in Chinese companies.

2.2 Upstream Distributions

It is usually easier from a corporate law perspective to contribute shares in companies downstream. However, for a variety of other reasons, it may be preferable to distribute shares in companies upstream. From a corporate law perspective, an upstream distribution can be achieved either by declaring a dividend out of distributable reserves, or by way of a capital reduction, the latter being likely to be a more cumbersome, time consuming and costly procedure. Again, tax effects may be seen at three levels. Firstly, is the distribution taxable in the jurisdiction of the company receiving the distribution? Secondly, at the level of the company making the distribution there are two issues to consider, is the distribution subject to withholding tax in the jurisdiction of the company making the distribution and, is the distribution a taxable disposal of the shares? This second issue can be a difficult one as many countries, such as the United States, have complex requirements which must be satisfied for an upstream distribution to be tax free. At the third level the tax consequences in the jurisdiction of incorporation of the company being distributed must be considered (see the issues discussed in paragraph 2.1 above).

2.3 Sale of Stock within the Corporation

The third option is to sell the company directly to another company, which can immediately achieve the relevant parent/subsidiary or brother/sister relationship. This method is sometimes the simplest, especially where a complicated group structure means distributions and/or contributions are impractical. The tax issues discussed above are again relevant.

The sale method can also have other beneficial effects, which can include cash repatriation and the opportunity to leverage local companies with debt.

A company in a particular jurisdiction may be cash rich. This situation may have arisen because current cash generating operations are being used to reduce an earnings deficit on its balance sheet; the parent company has decided not to repatriate cash using dividends because it would become trapped in an intermediate subsidiary that has an earnings deficit (a so-called “dividend blocker”); or it is not tax efficient to distribute profits, either because of the effect of non-creditable withholding taxes or high tax charges in the home jurisdiction of the parent or any intermediate company. The sale of shares in a company or of the underlying business and assets of a company can be used to extract surplus cash out of these types of subsidiaries. In the case of an asset sale, the cash may be further extracted from the company selling the assets either by way of a liquidation, or by utilizing any realized profits on the sale of its assets to declare a dividend.

A sale of shares and/or assets to another company within the group may achieve other benefits. For example, where the original acquisition has been substantially funded by debt, the borrowing company may not have sufficient domestic tax capacity to absorb deductions for the entire financing costs. A primary objective in this situation is to enable maximum tax relief to be obtained for the funding costs in those jurisdictions which have companies with significant tax capacity and this can be achieved by the borrowing company selling shares in subsidiaries (and/or assets) to relevant local subsidiaries with tax capacity.

It is important to examine whether local law will permit a deduction in respect of interest paid in connection with a debt incurred in such a manner. Some countries disallow the deduction in certain circumstances. For example, Singapore does not permit deductions for debts incurred to acquire assets that produce income which is not taxable in Singapore. This includes shares in Singaporean and foreign companies. However, in Singapore it is possible to obtain a deduction for debt incurred to purchase a Singaporean business. In many jurisdictions deductions are not permitted for debt which is incurred for the sole purpose of creating tax deductions. The integration project itself can provide a commercial business purpose for this type of planning.

Other techniques which may be used to create tax deductible interest in a local jurisdiction might include declaring a dividend and leaving the dividend amount outstanding as a debt or undertaking a capital reduction with the payment left outstanding as a debt.

The sale of assets and/or shares across the group also provides an opportunity to rationalize or make more tax efficient the group’s intercompany debt position. For example, a company may assign an intercompany receivable as consideration for the purchase of an asset and/or shares.

3. Tax Issues

3.1 Tax Decrees and Authorizations

Tax authorities in many jurisdictions make provision for binding advance rulings confirming the tax treatment of a transaction in advance of it being implemented. As tax rules around the world become increasingly complex, and the financial reporting requirements associated with the disclosure of uncertain tax positions become more onerous, obtaining certainty as to the tax treatment of a particular transaction as early as possible will often be hugely advantageous. On the other hand, rulings can be costly and time consuming to prepare. Moreover, applying for rulings can lead to audits by local tax authorities, which can impose additional burdens on internal resources that are already stretched by the integration planning and implementation process.

The following factors should be considered in determining whether or not to seek a ruling:

- is an advance ruling necessary to achieve the intended tax result? In France, for example, NOLs will not transfer on a merger unless a prior advance ruling is obtained from the French tax authorities;

- how important is obtaining certainty in advance of the transaction? Groups that are subject to US financial reporting requirements may place a higher premium on certainty than groups that are not;

- is a ruling the only way to obtain the level of certainty required? Where the tax rules relating to a particular transaction are fairly clear, an opinion from third party advisors may provide sufficient comfort on any points of uncertainty;

- how much will the ruling cost? Tax authorities in some jurisdictions (for example Germany) can charge a substantial fee for providing advance tax rulings;

- how long will it take to get the ruling? Tax authorities in some jurisdictions (for example the UK) commit to providing a response to ruling requests within a certain time-frame, whereas others are not obligated to respond at all. This can lead to the ruling process holding up the timing of the transaction as a whole;

- how much disclosure is required? Most tax authorities require that the taxpayer fully disclose all of the details of the transaction before they provide a ruling. Where a new operating or transfer pricing structure is being implemented, the group may feel that early disclosure may result in a less advantageous tax result (for example where the advance agreement will be based on potentially unreliable forecast data); and

- can the ruling be relied upon? Some rulings are more binding than others. In some jurisdictions, a “ruling” is, in reality, merely a written indication of the way in which the tax authorities are likely to view the transaction, which can be departed from on audit.

3.2 Managing Real Estate Tax Transfers

Many jurisdictions impose transfer taxes on the transfer of real estate. Some (for example Germany) also impose transfer taxes on the (direct or indirect) transfer of shares in companies that own real estate in that jurisdiction. As real estate transfer taxes tend not to be deductible for tax purposes nor creditable in the jurisdiction of a parent entity, they generally represent a real out-of-pocket cost to the company.

In many jurisdictions (for example the Netherlands), real estate transfer tax only applies to an indirect transfer of real estate where the company whose shares are transferred is considered “real estate rich”. This can create a tension between commercial considerations, which will sometimes militate towards holding real estate in a separate legal entity to ring-fence liability, and tax considerations, which might suggest holding real estate in an operating entity so that the value of other assets “swamps” the value of the real estate, preventing the company from being considered “real estate rich”.

In practice, exemptions are often available where the real estate (or an interest in the real estate) is transferred within an associated group of companies, which limit the impact of real estate transfer taxes in the context of intra-group reorganizations. For example, the transfer of a company incorporated in New South Wales, Australia is subject to a 0.6% stamp duty, but relief is granted where the transferor and transferee company have been associated for at least 12 months prior to the transfer. However, some jurisdictions (for example Germany) have extremely limited exemptions. In these jurisdictions, it is often necessary to consider bespoke transfer tax mitigation structures to limit the incidence of real estate transfer tax.

3.3 Intellectual Property Migration

Intellectual property represents an important and valuable asset for many groups. Where such assets are owned by entities in high-tax jurisdictions, this can have a significant effect on the group’s overall effective tax rate. Post-acquisition integration often provides a good platform for a reconsideration and rationalisation of a group’s IP holding structure, which in turn can create material tax efficiencies.

Even where IP migration is not an option, it is sometimes possible to structure a merger or business transfer in a way that gives rise to goodwill that can be amortized for tax purposes by the acquiring entity, thus eroding the local tax base post-integration.

3.4 Tax Financial Structure

Post-acquisition integration also often provides an ideal opportunity to rationalize or make more tax efficient the group’s financing structure. For example, a company may assign an intercompany receivable as consideration for the purchase of an asset and/or shares, or may sell assets and/or shares across the group in exchange for debt, as discussed at paragraph 2.3 above. In some cases, it may be possible to make use of “hybrid” instruments in these transactions, the effect of which is that a deduction is available in respect of “interest” paid by the debtor, whereas the return on the instrument is regarded as a tax-exempt return on equity in the hands of the creditor.

In all cases where more tax efficient financing is aimed for, local thin capitalisation limits have to be observed in the planning to avoid “vagabonding” interest i.e. creating interest costs which are not deductible anywhere.

4. Integration Framework for Local Operations

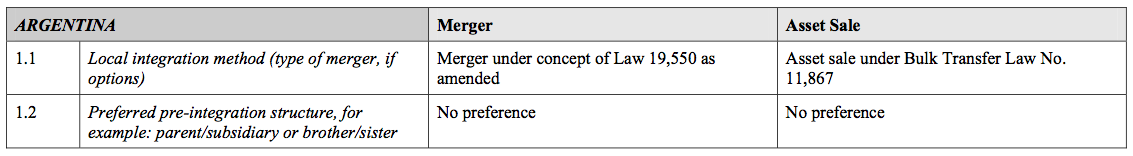

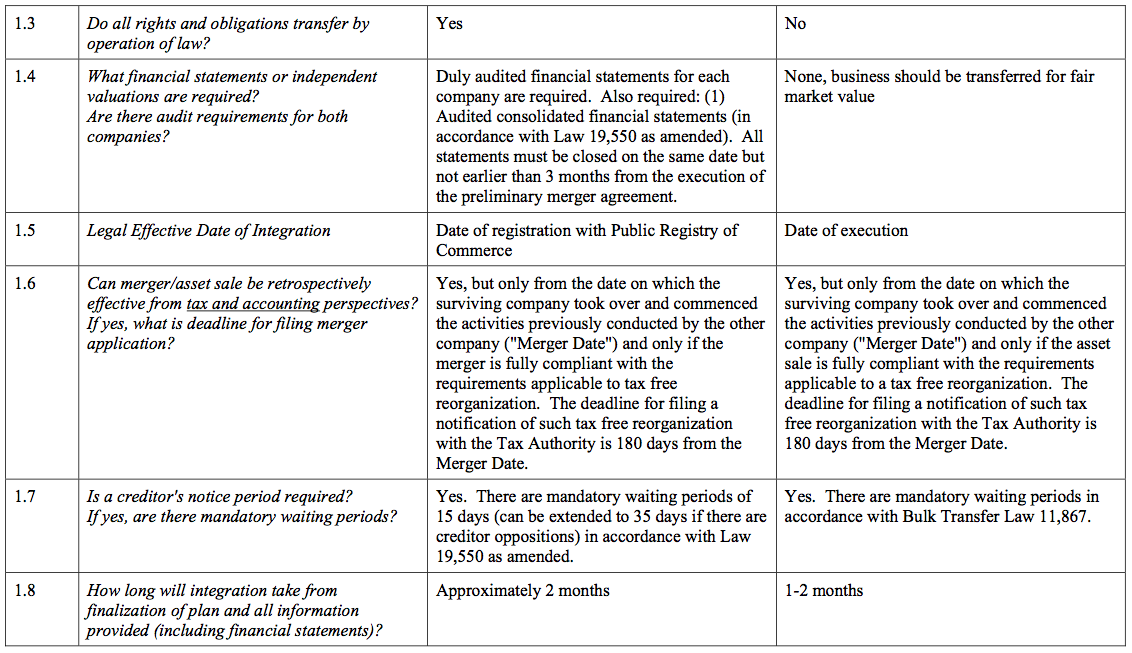

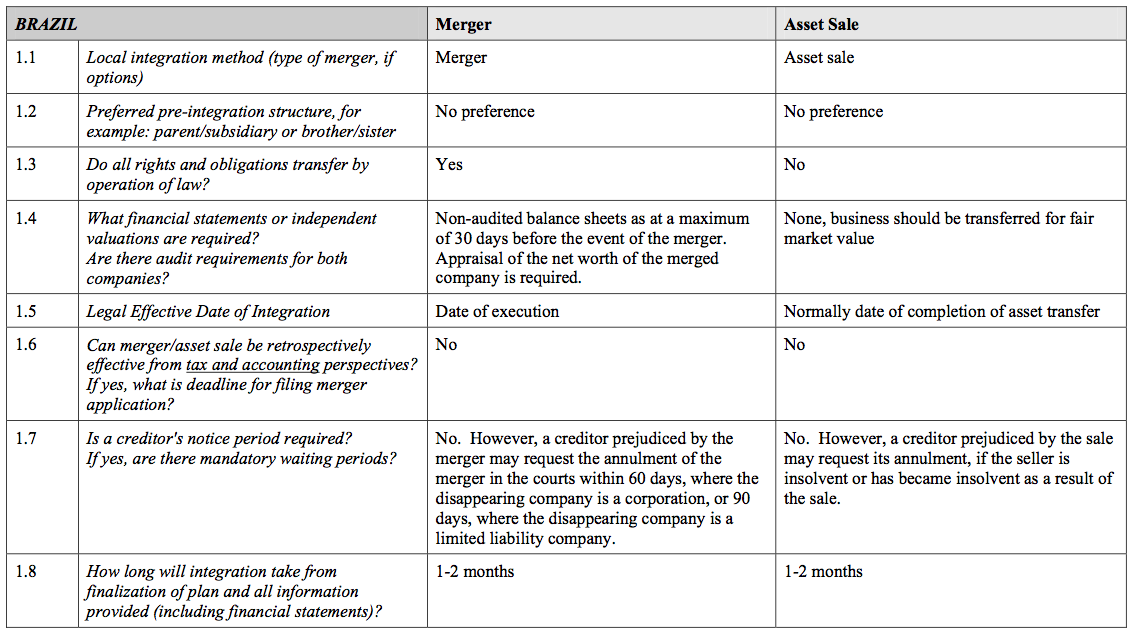

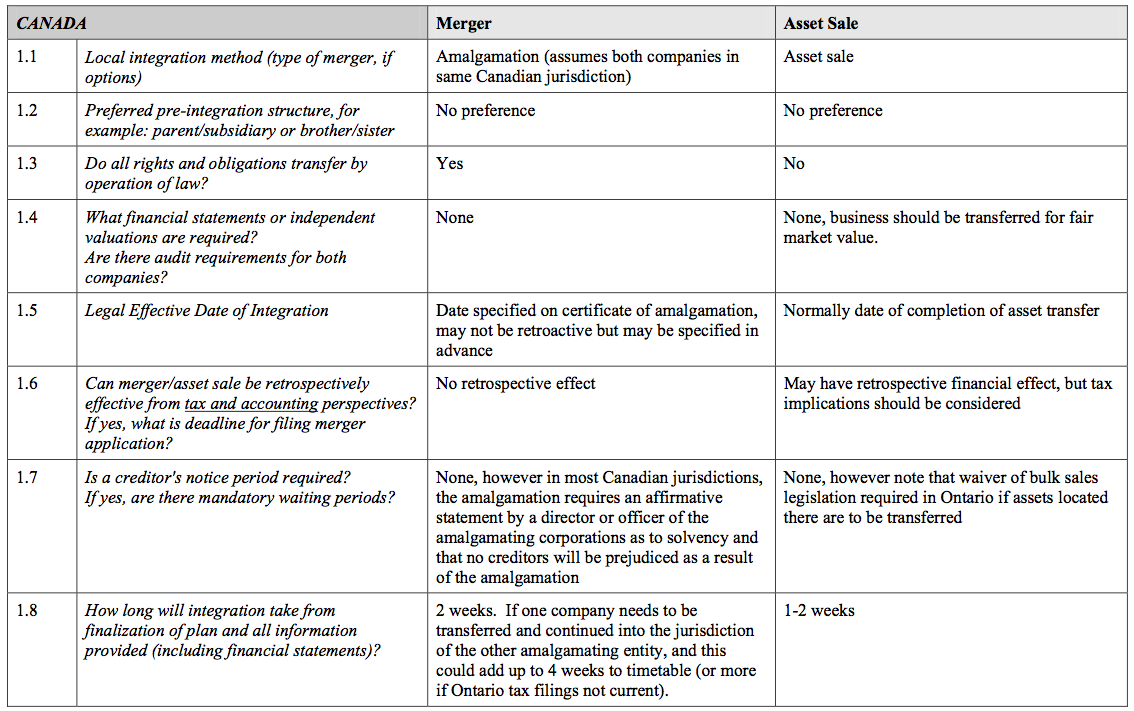

There are two basic methods available to integrate operations in local jurisdictions: either a statutory merger under local law; or the sale of business from one subsidiary to another in the same jurisdiction with a subsequent liquidation of the seller. A summary of these integration methods in thirty three jurisdictions is set out in Section 10.

4.1 Sale, Consolidation, and Liquidation of Business

The simplest approach to achieve the consolidation of operations is often to sell the business of one foreign subsidiary to the other subsidiary in the same jurisdiction. The selling company is subsequently liquidated. In most common law jurisdictions, including the United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa and Singapore, either no simplified statutory merger regime exists or if a regime exists it is, for practical reasons, not commonly used. In these jurisdictions a business sale and liquidation is the only available way to integrate the businesses. The tax goal in carrying out such transactions is to minimize or eliminate any tax charge and if possible to retain any valuable tax attributes of the local seller and the local buyer. To achieve this goal it is usually necessary to have the seller and the buyer either in a group arrangement or consolidated for local tax purposes. In certain jurisdictions this may only be possible if one local company directly owns the other or they are both owned by a common parent company in the same jurisdiction. In the United Kingdom and Australia the tax rules allow for common ownership to be traced through foreign corporations, which can eliminate the need to undertake any share restructuring prior to the consolidation.

When transferring assets from one company to another it is likely that the assets will be treated for tax purposes as being sold for their fair market value unless the asset can be transferred from one group company to another on a tax-neutral basis pursuant to local tax group or consolidation rules.

Management should always consider whether they wish to take advantage of these regimes or whether a better result can be achieved by ensuring that the rules do not apply. The tax impact of the sale of assets out of the country, in particular if IP and/or goodwill/customer relations etc. are included, has to be carefully considered from the perspective of exposure to “transfer of functions” taxation under OECD principles and even tighter local rules, such as those applicable in Germany.

The transfer of trading stock and work in progress from one company to another company in the same jurisdiction will normally give rise to a revenue profit. Local tax rules may allow for such assets to be transferred at their original acquisition cost, although consideration should always be given as to whether existing NOLs within the selling company might be used (always subject to local minimum taxation rules, if any) to set off against any profits arising from a sale at fair market value. This allows the buying company to achieve a step-up in its tax base cost in these assets and is a useful technique if the transfer of NOLs from the local selling company to the local buying company is not possible.

The selling company may have been depreciating its capital assets for tax and accounting purposes. The effects of any intercompany sale upon tax depreciation claims should be considered. In some jurisdictions, opportunities exist for pre-acquisition tax depreciation allowances to be disclaimed and deferred to a post-acquisition period. This can be useful to help mitigate the loss of NOLs, which can occur as a result of the original acquisition or the post-acquisition integration. In some situations companies may not want NOLs or other tax attributes to transfer as part of an asset sale to the identified surviving company, for example a US parent company may have been utilising in the US the NOLs of a foreign branch. If the foreign branch NOLs transfer to a foreign subsidiary of the US parent company as a matter of local law, the US parent may be faced with the recapture of the US tax savings generated as a result of using its foreign branch’s NOLs in the US.

In most jurisdictions the sale of assets from one company to another will be subject to value added tax or a similar tax. Usually such tax charged by the selling company to the buying company is creditable to the buying company, however, this can give rise to a cash flow disadvantage to the group when carrying out such transactions in a large number of jurisdictions. In many jurisdictions, and this is certainly true for EU member countries, transfers of businesses as a going concern are ignored for VAT purposes.

Stamp duties can considerably add to the cost of a local asset sale, especially when valuable real estate is being transferred from one company to the other. Fortunately, reliefs are usually available. Any such reliefs may dictate the manner in which the sale takes place, for example it may be structured as an assets-for-shares sale or the sale may have to be delayed until a particular group relationship has been in place for a relevant holding period.

4.2 Local Statutory Merger

When available, the recommended approach is often to use a statutory merger under local law. Such a transaction will typically (though not always) be tax-free from a local tax perspective, although post merger conditions may also apply. Depending upon the jurisdiction, the tax attributes of the target or absorbed company may or may not carry over. In particular, in a number of jurisdictions the future availability of the NOLs of the absorbed company will be restricted or lost entirely. In such jurisdictions, it is often preferable to make the company with the NOLs the survivor, if possible within the objectives of the integration and under local law.

Real estate transfer taxes are still chargeable on mergers in many jurisdictions, and these costs may dictate that the company with no real estate or the least valuable real estate is the disappearing company in a merger.

Again the local tax treatment of a merger is just one consideration. The tax treatment on a global level should always be considered. When two local companies merge whilst in a brother/sister relationship, or a local parent company merges downstream and into its local subsidiary, any foreign shareholder is likely to be treated as disposing of its shares in the disappearing company for foreign tax purposes. It may be that there is no foreign tax charge because of a relevant participation exemption, the application of the EU Merger Directive, foreign tax laws classifying the merger as a tax-free reorganization, the utilisation of existing NOLs by the foreign company, or simply because the foreign shareholder has a base cost in the disappearing local entity equal to its market value as a result of the prior transfer to it of the shares in the disappearing company as part of the integration planning.

In many jurisdictions, a merger will have a retroactive effective date for tax or accounting purposes. A retroactive effective date can allow for earlier consolidation and utilization of favorable tax attributes, such as NOLs.

The desirability of utilizing merger regimes from a tax perspective must be weighed against operational objectives, which sometimes can be frustrated by the merger process. Merger regimes often require the preparation and filing of recent balance sheets or full accounts of at least the absorbed company and in many cases these accounts will need to be audited. The time required to prepare such accounts, combined with mandatory waiting periods to protect creditors after a public notification has been made can frustrate the operational need to combine the local business of the target company with that of the acquiror quickly so that business efficiencies and management control are achieved.

Finally, a comparatively recent development is the EU cross-border merger which can be used to simplify corporate structures in the EU and economize on compliance costs. In this scenario, a company in one member country can be merged cross-border into another company, leaving behind a branch, for tax purposes a permanent establishment, with the assets and liabilities of and the business as formerly conducted by the merged entity. In most cases such merger can be conducted without realisation of taxable income, although other tax attributes such as NOLs may not remain available in some countries (for example Germany), although they remain available in others (for example Austria).

4.3 Alternative Approach to Business Consolidation & Merger

Many jurisdictions have some form of group or consolidated tax regime that can be used as an alternative to a tax-free asset sale or merger (for example UK group relief, French consolidation, and German Organschaft). Essentially, this approach allows the two operations to share NOLs and to obtain the benefits of consolidation from a tax perspective, but it does not consolidate activities on a business and operational level. Thus, this approach is not recommended where an actual consolidation is desirable and can be completed. This method can be effective if there are limited overlapping activities or redundancies, structural tax constraints or costs preventing operational consolidation.

Another alternative to an actual consolidation is a lease by one company of its entire business to the other company. This approach does allow the parties to consolidate on an operational level. For transfer pricing purposes the lessor must earn an arm’s length profit on the leased business.

This structure may be useful in two particular circumstances. The first situation is where the surviving company in a jurisdiction wishes to use the assets of the disappearing company in its business, but cannot immediately acquire them. This may be because permits, licenses, or leases cannot be assigned without consent, or the companies are not yet in the optimum structural relationship from a tax perspective to consummate a business sale.

In France, Germany, Austria, and certain other jurisdictions the business lease is a method used to prevent the company which is identified as the disappearing company prematurely being treated as disposing of its assets to the surviving company as a result of the surviving company utilizing such assets in its business prior to their legal transfer.

Such a deemed disposal of assets can have unfortunate tax consequences if the companies are not in the correct relationship at the time and negate the benefit of a subsequent tax-free merger.

The second scenario is where trading NOLs in the disappearing company will not transfer to the surviving company. It may be possible to use these NOLs effectively by claiming a deduction for the leasing expense in the surviving company and off-setting the NOLs in the disappearing company against its leasing profits.

5. Conclusion

As the above discussion demonstrates, the steps for integrating duplicate entities are similar and follow established patterns. The patterns are relatively well known and thus planning typically focuses on the preparatory steps to the integrations. These preparatory steps should allow the taxpayer to maximize the benefit of the domestic and foreign tax attributes, avoid unnecessary costs such as stamp taxes, and take advantage of one-time benefits. More importantly, this process allows the group to structure itself in a tax efficient manner that yields benefits for years to come. Although every integration project involves some new and unique planning issues, this chapter should serve as a road map for approaching the process, identifying the opportunities, and avoiding the pitfalls.

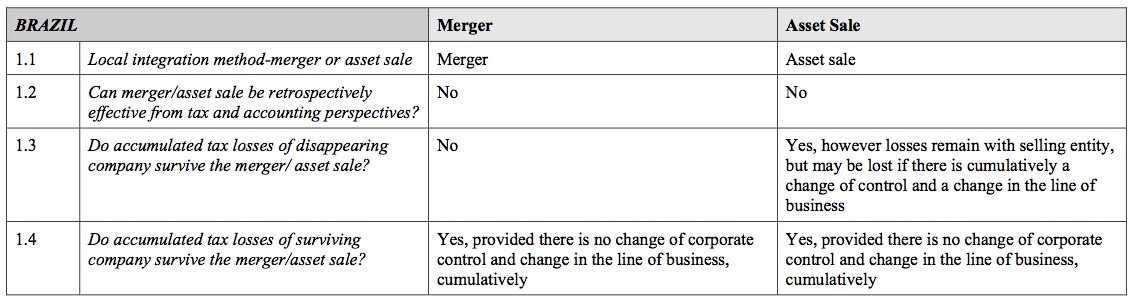

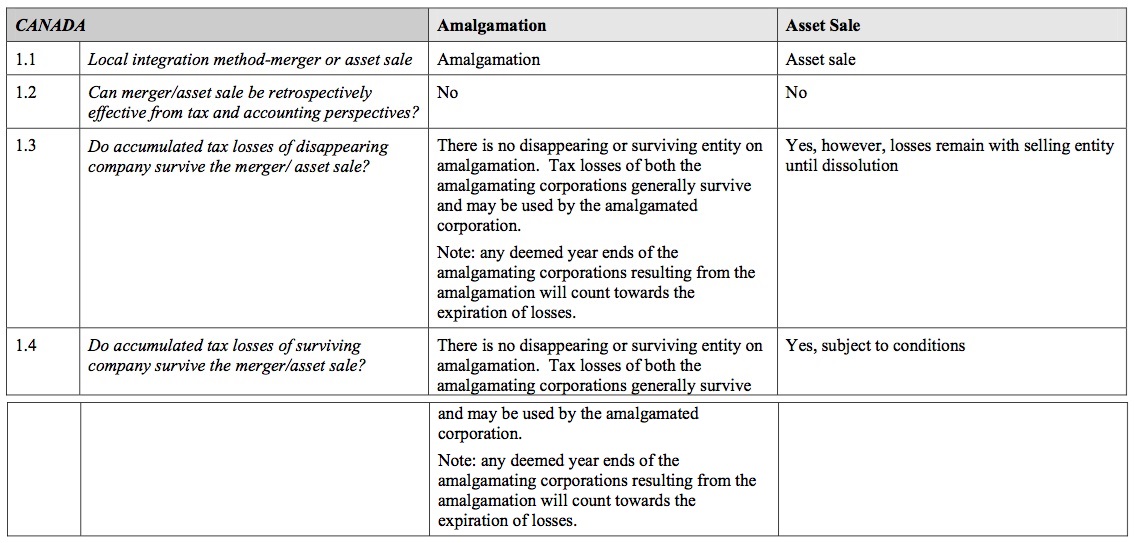

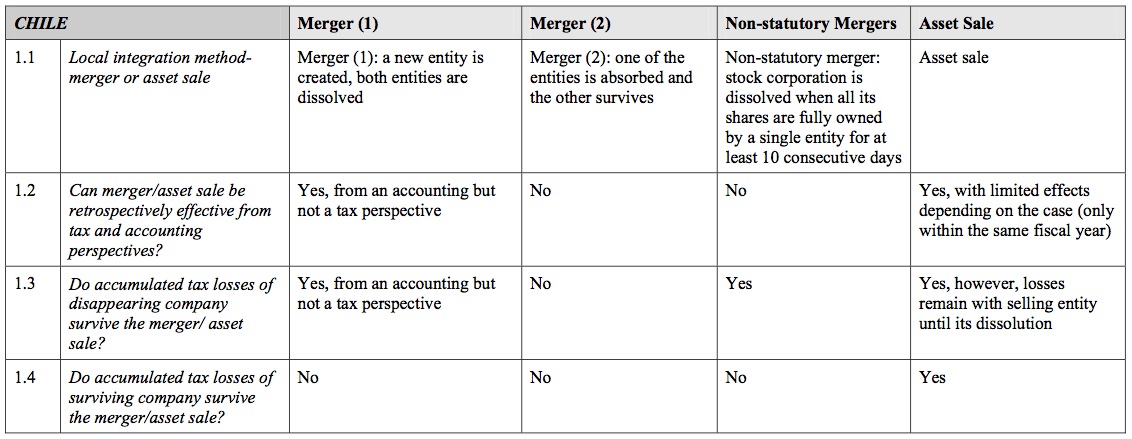

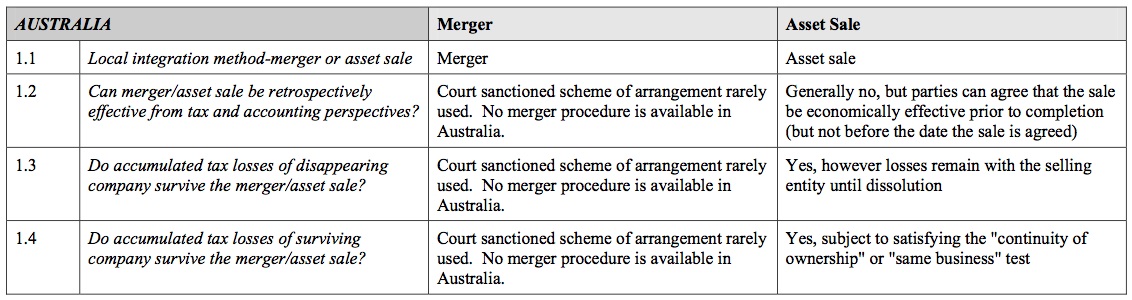

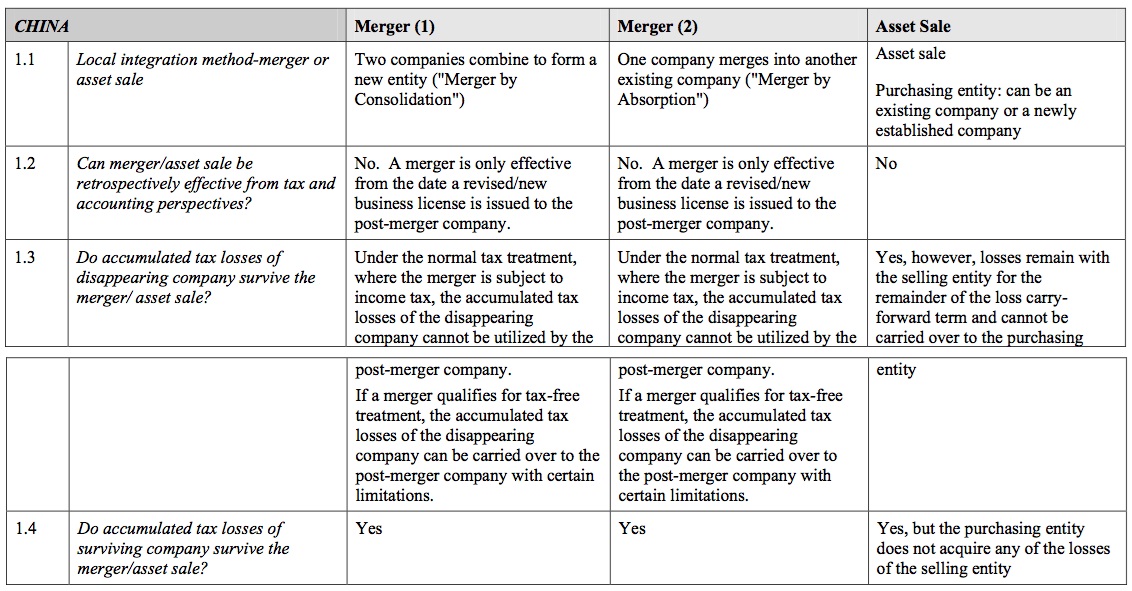

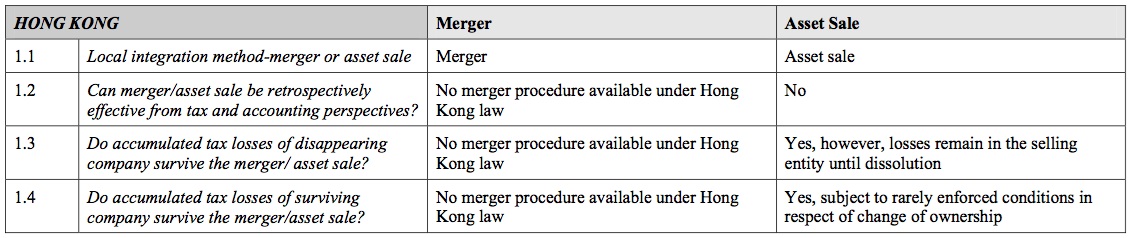

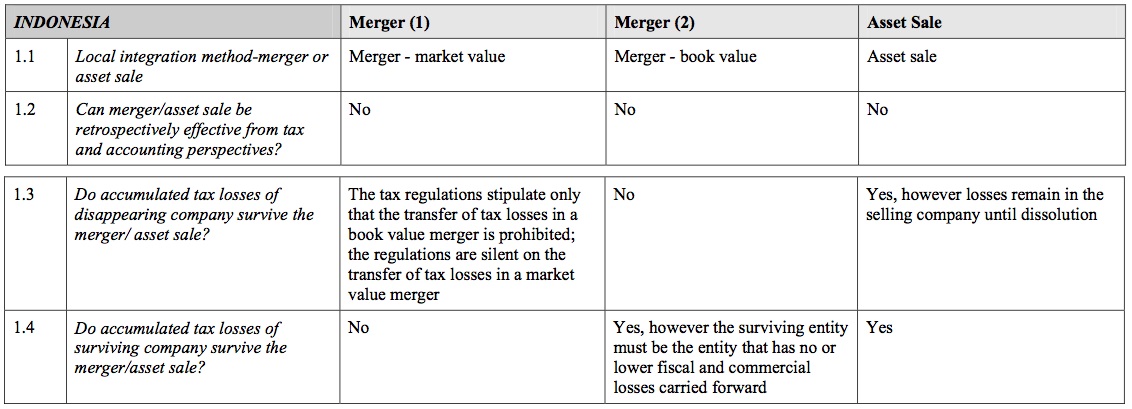

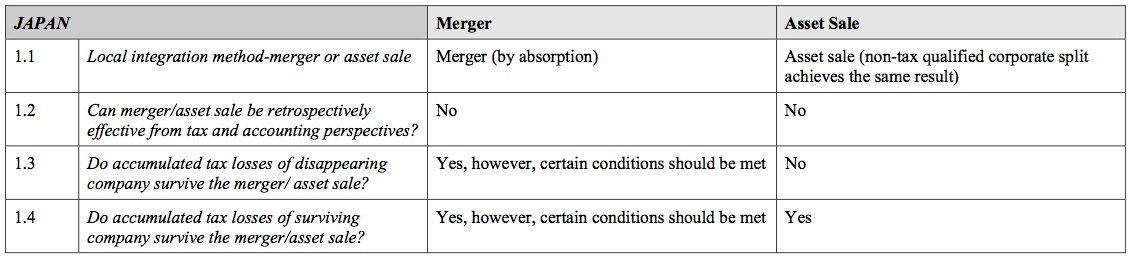

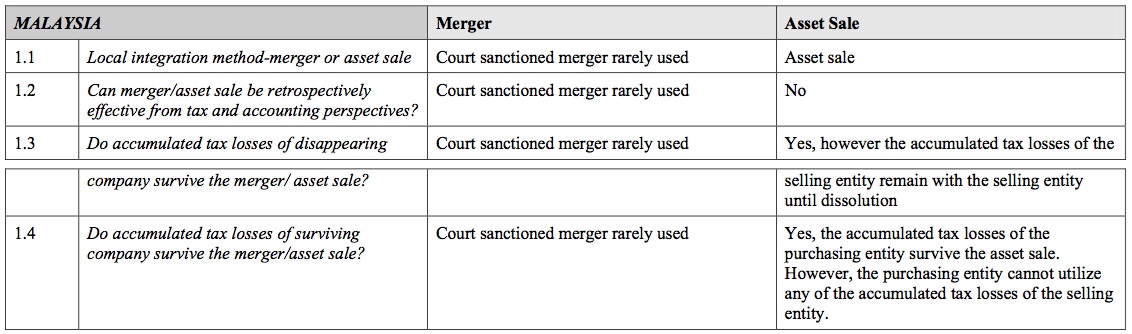

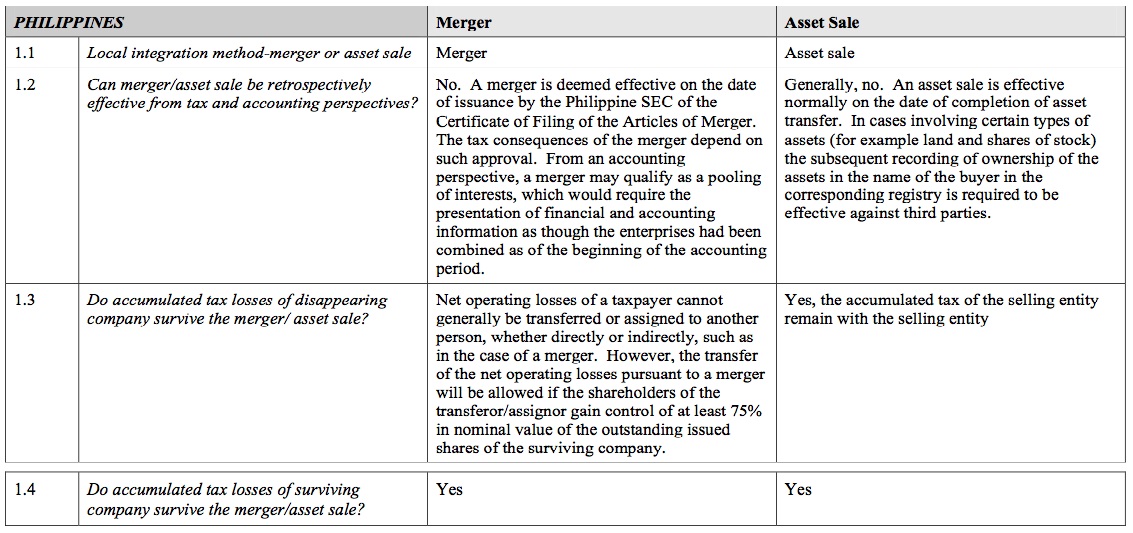

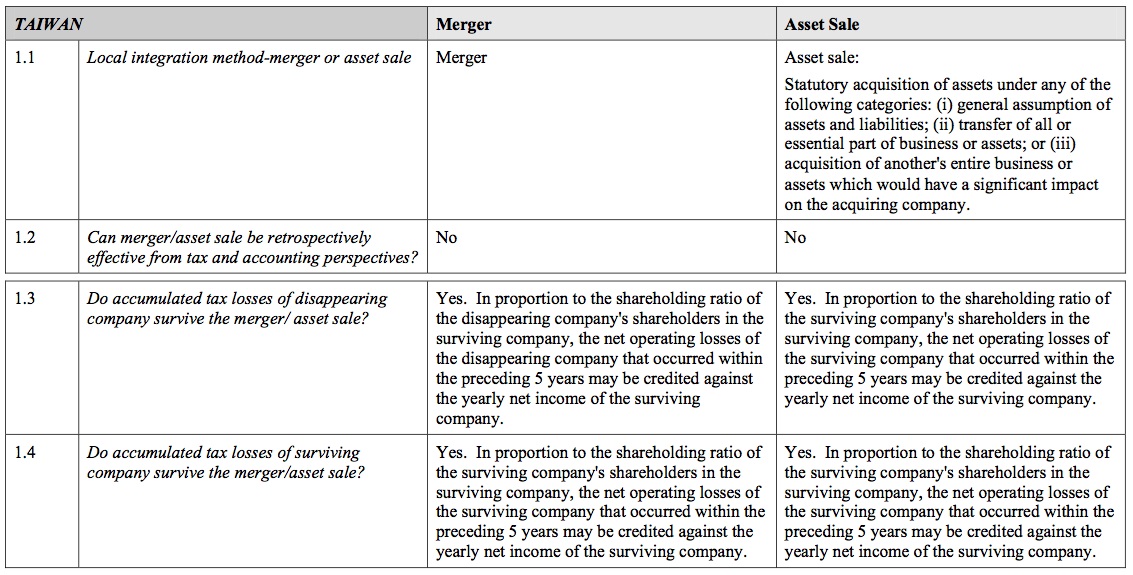

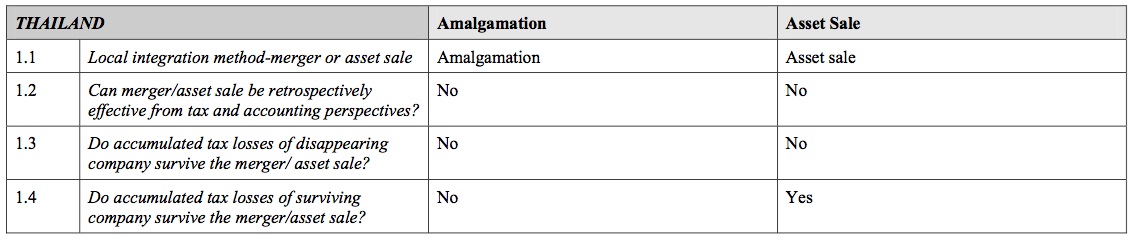

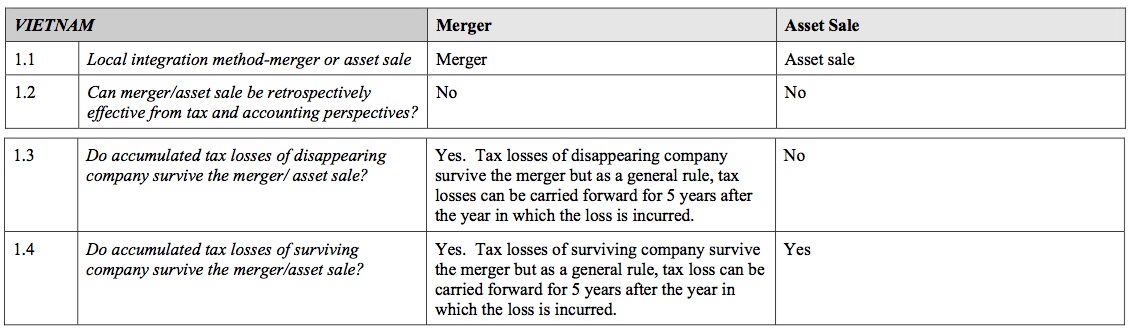

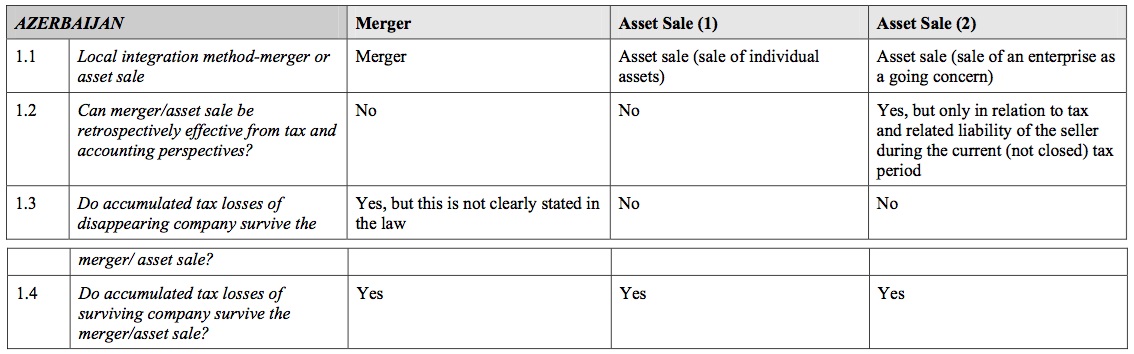

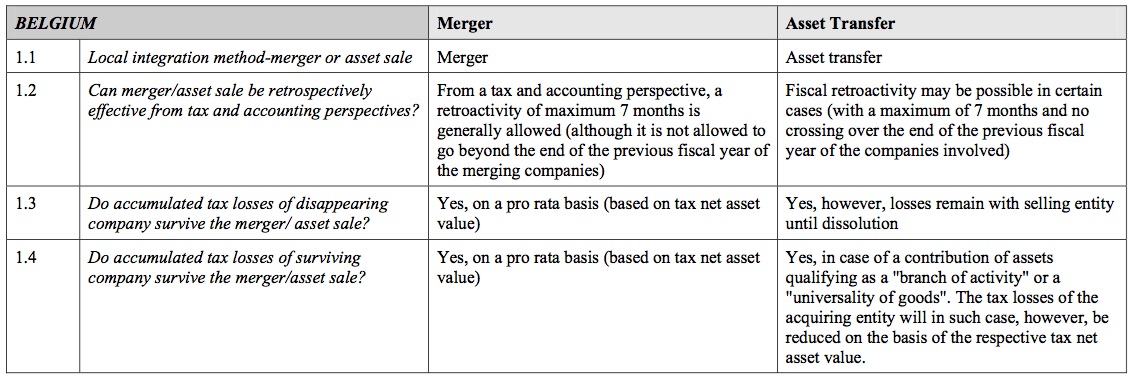

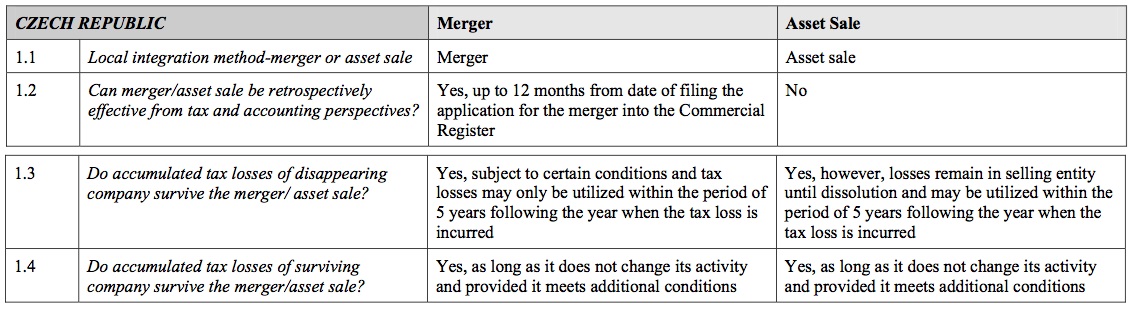

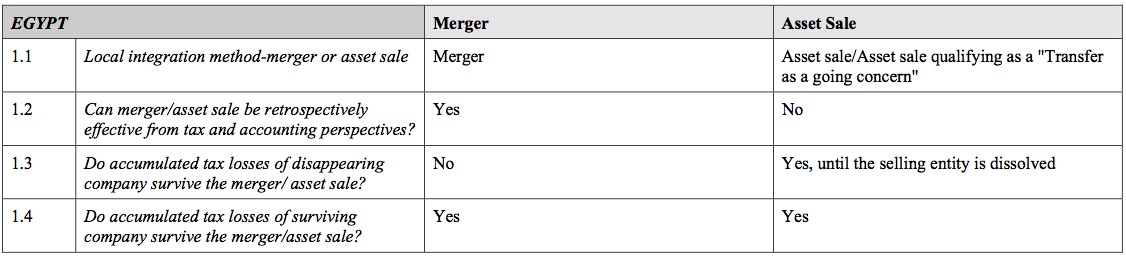

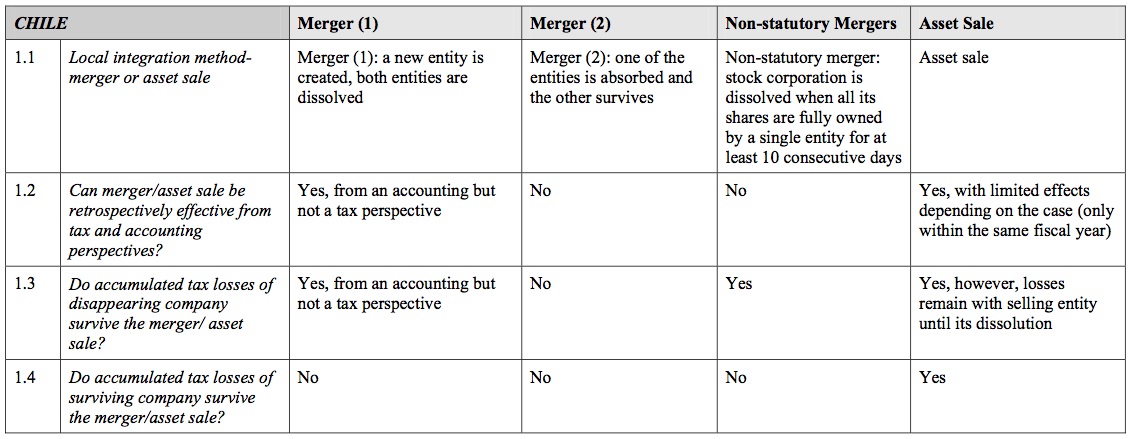

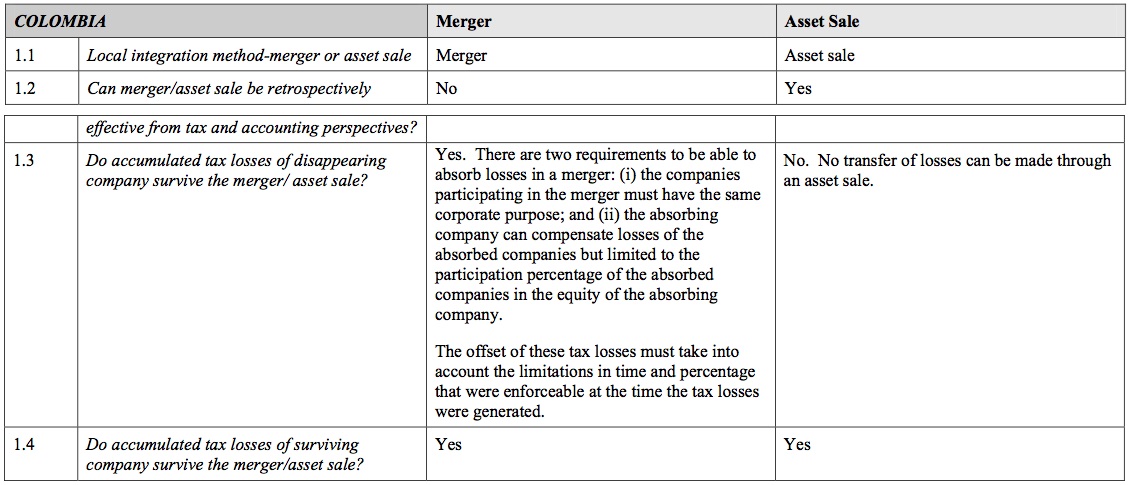

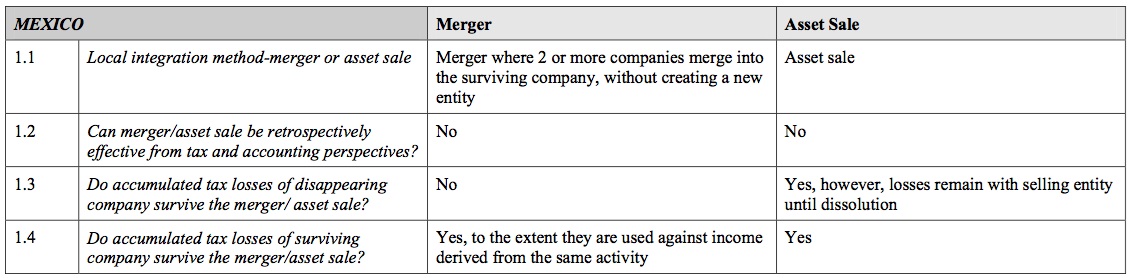

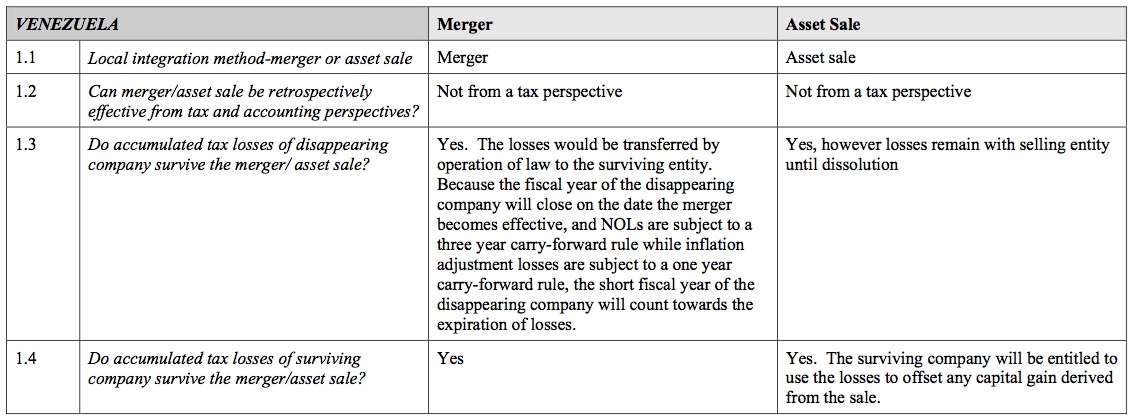

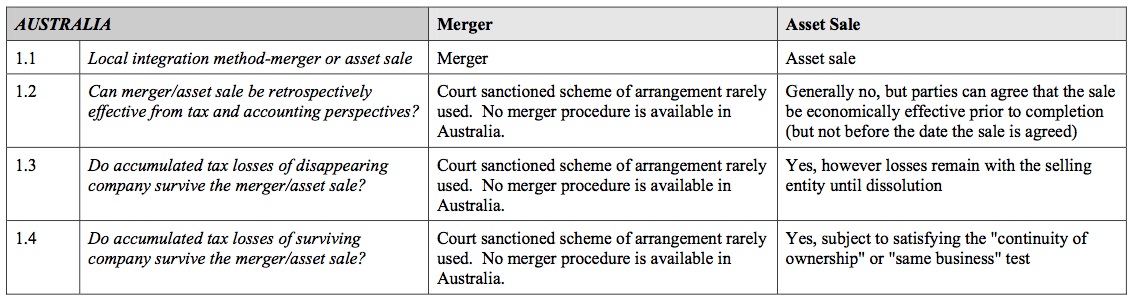

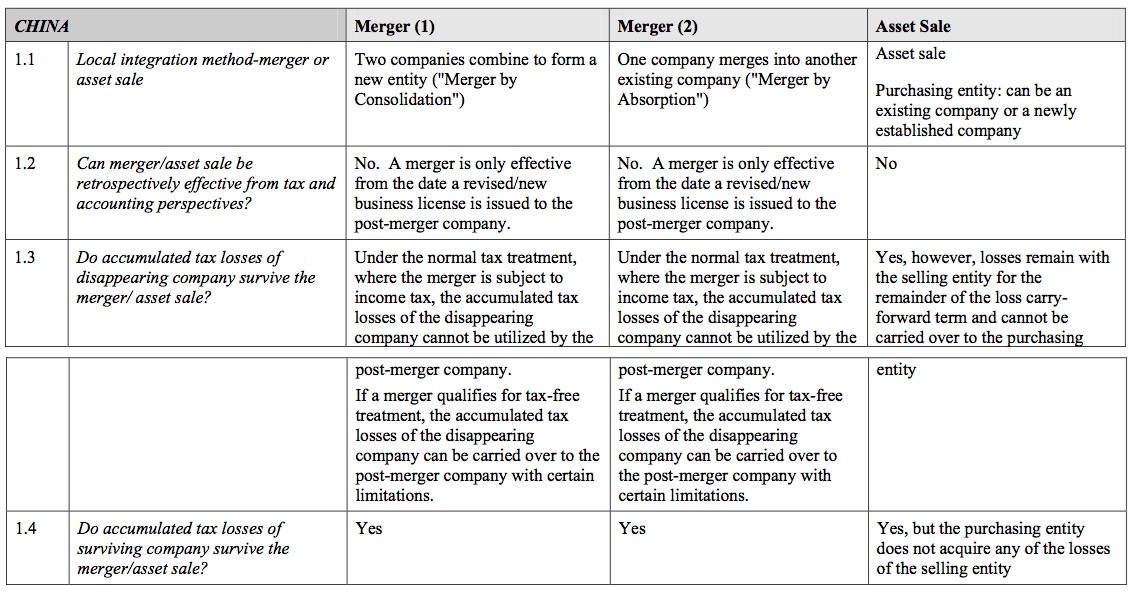

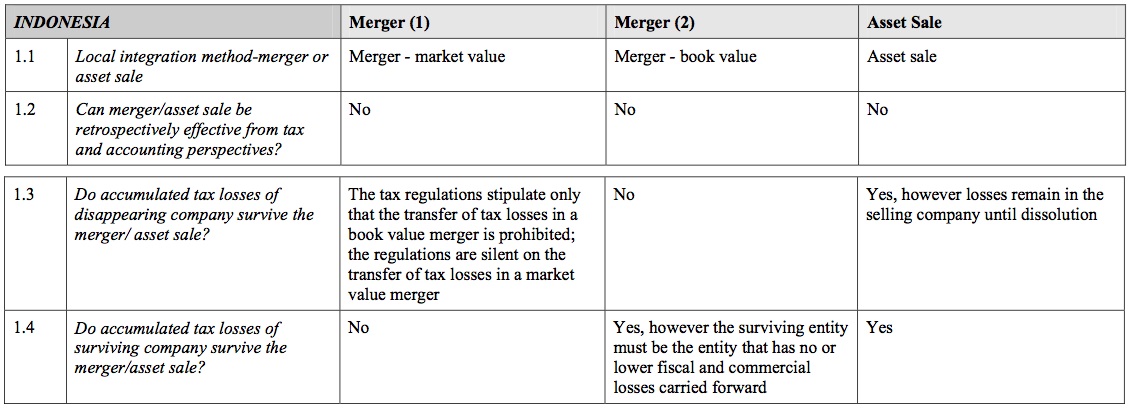

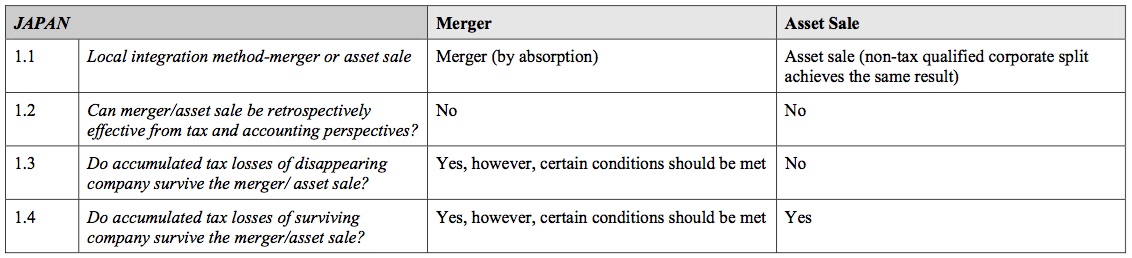

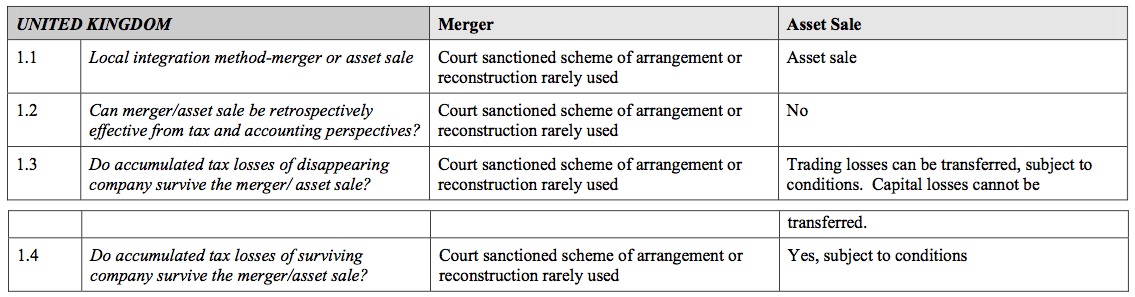

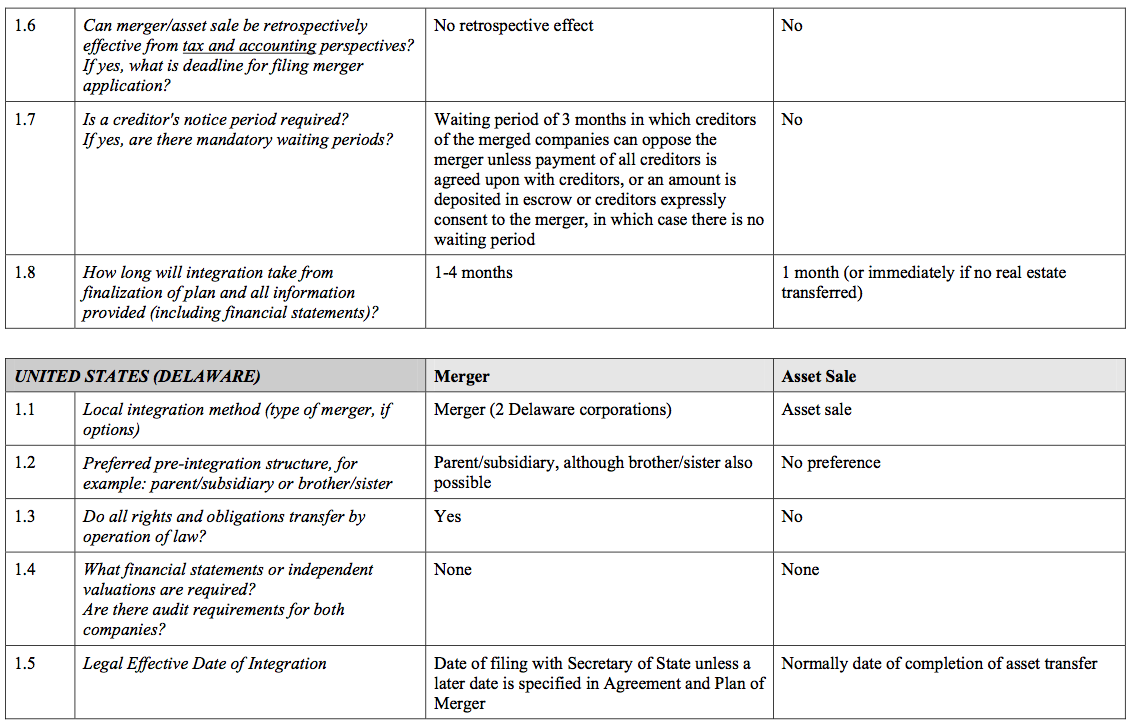

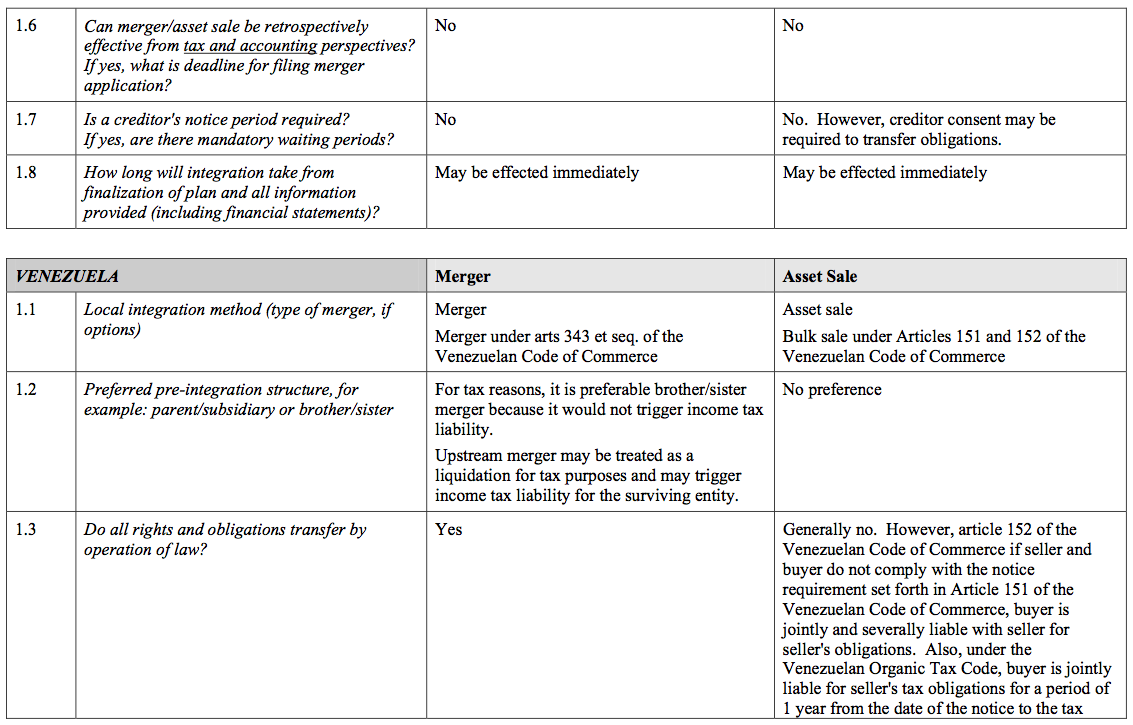

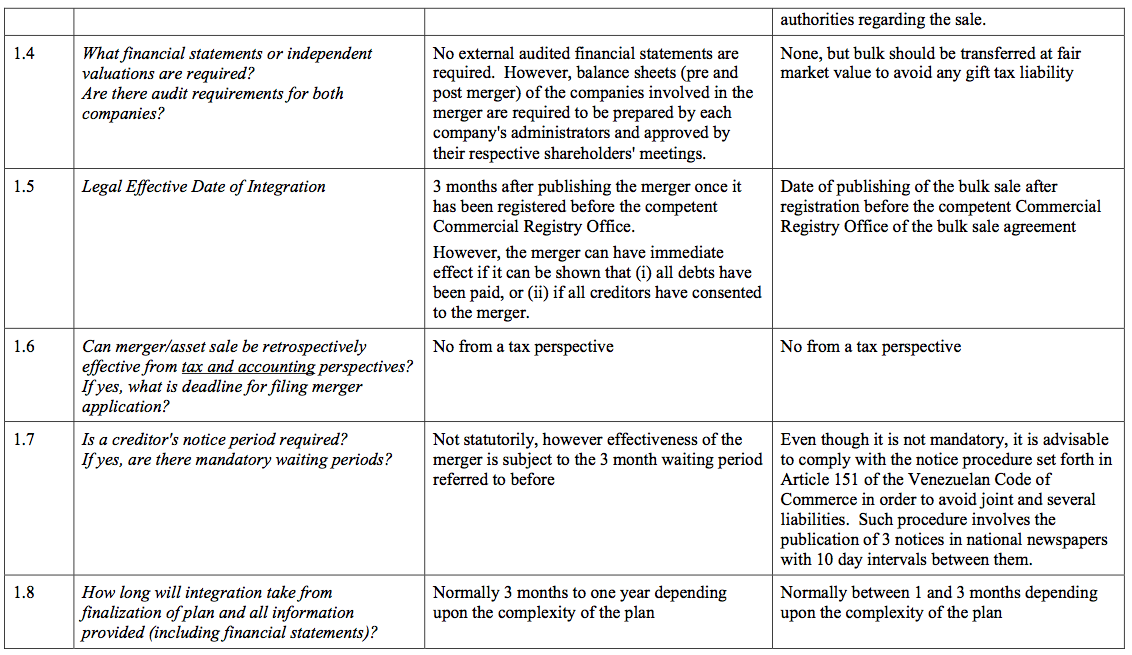

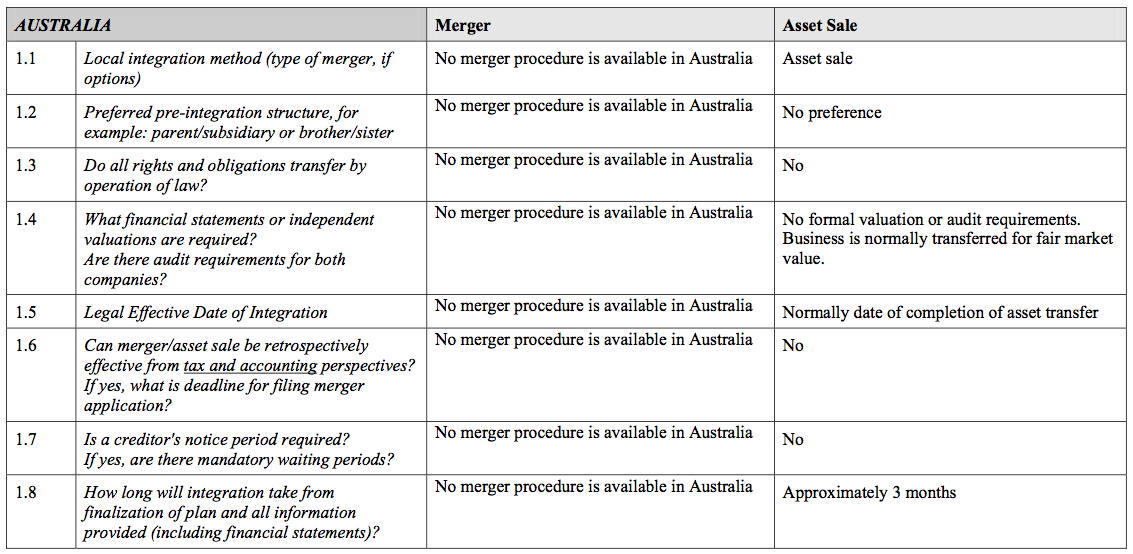

Analyzing Its Retroactive Effects and Tax Losses

When one multinational company acquires another company and its international subsidiaries, a key aspect of the integration of the two multinational groups is to consolidate duplicate operating companies so that there is only one operating company in each country. The following summary of integration methods has been prepared on the following assumptions.

(1) Each company is a 100% subsidiary of the same parent company or one is a 100% subsidiary of the other (subject to any mandatory minority shareholding interests).

(2) The surviving company of the integration will be one of the original operating companies, not a newly incorporated company. Alternate methods are available in many jurisdictions and this summary should not be relied on instead of obtaining specific legal advice.

1. AMERICAS

Brazil

Canada

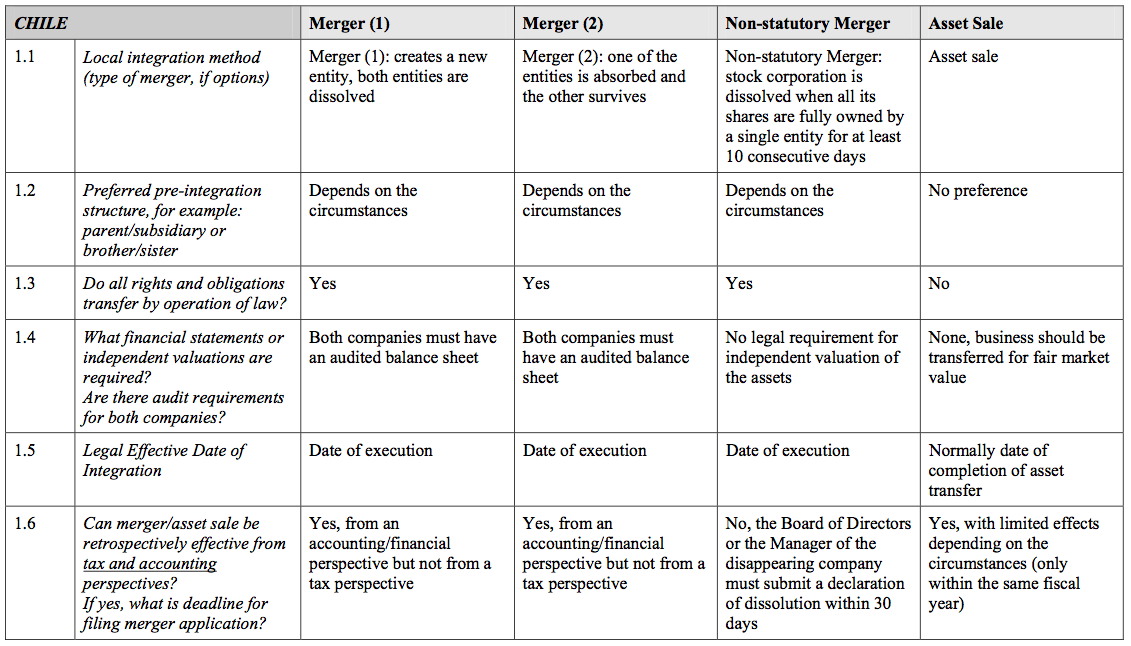

Chile

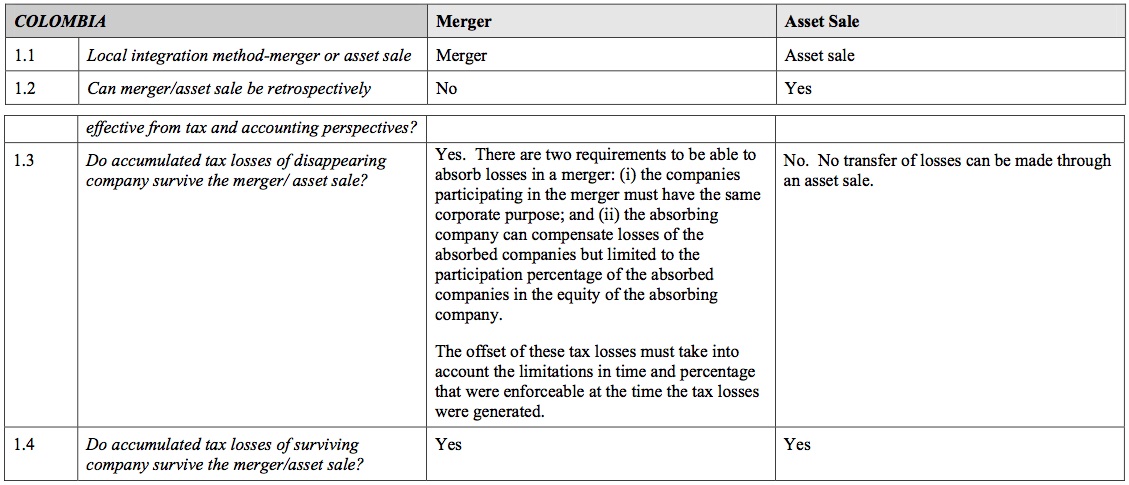

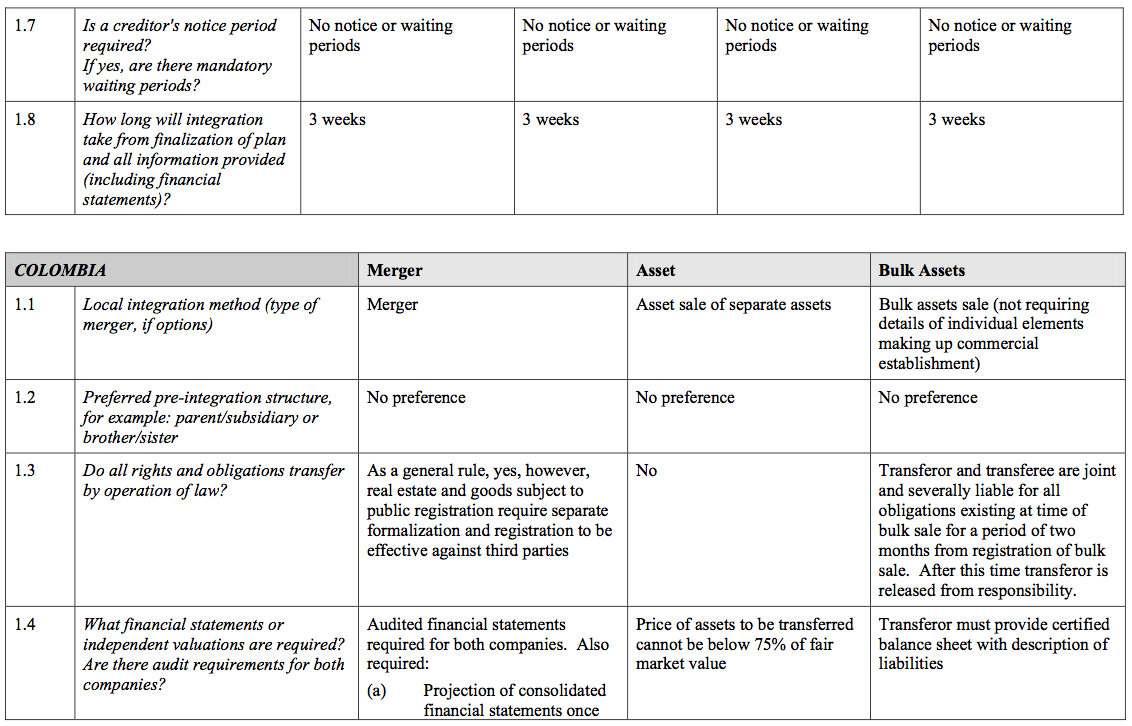

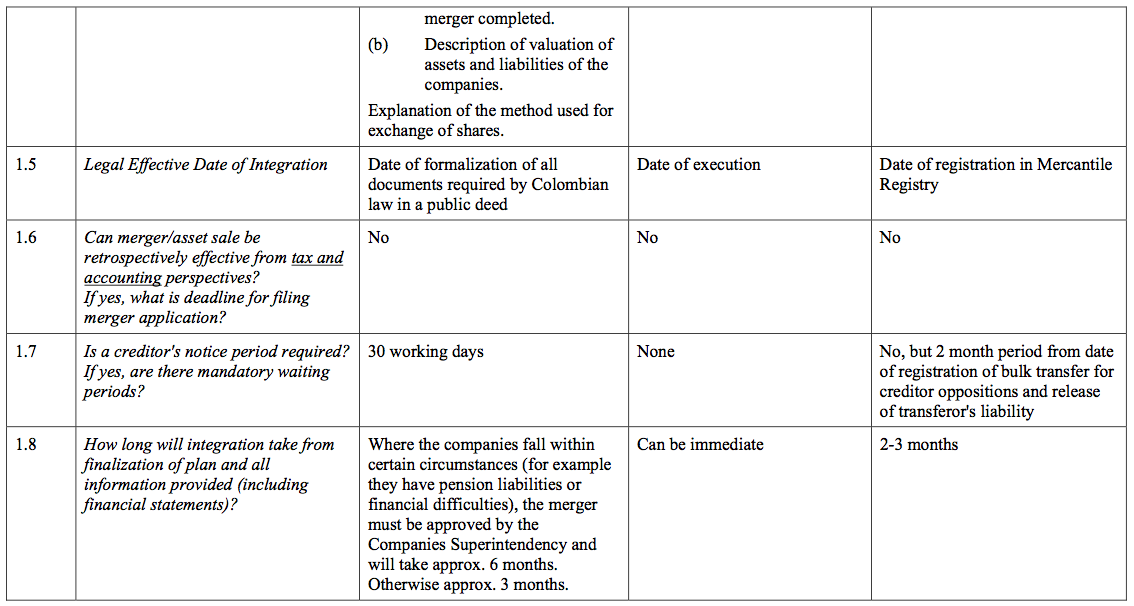

Colombia

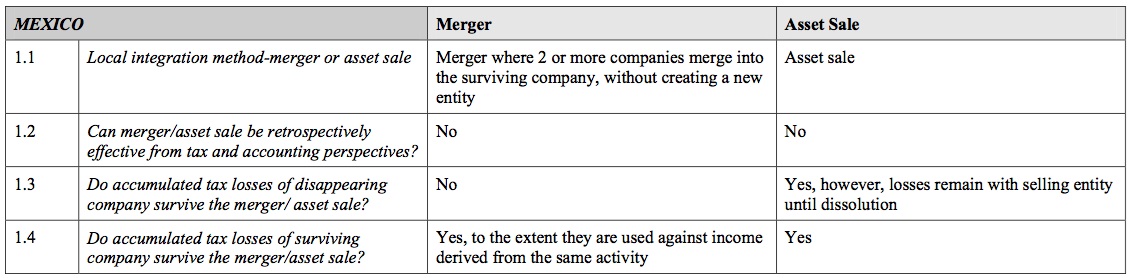

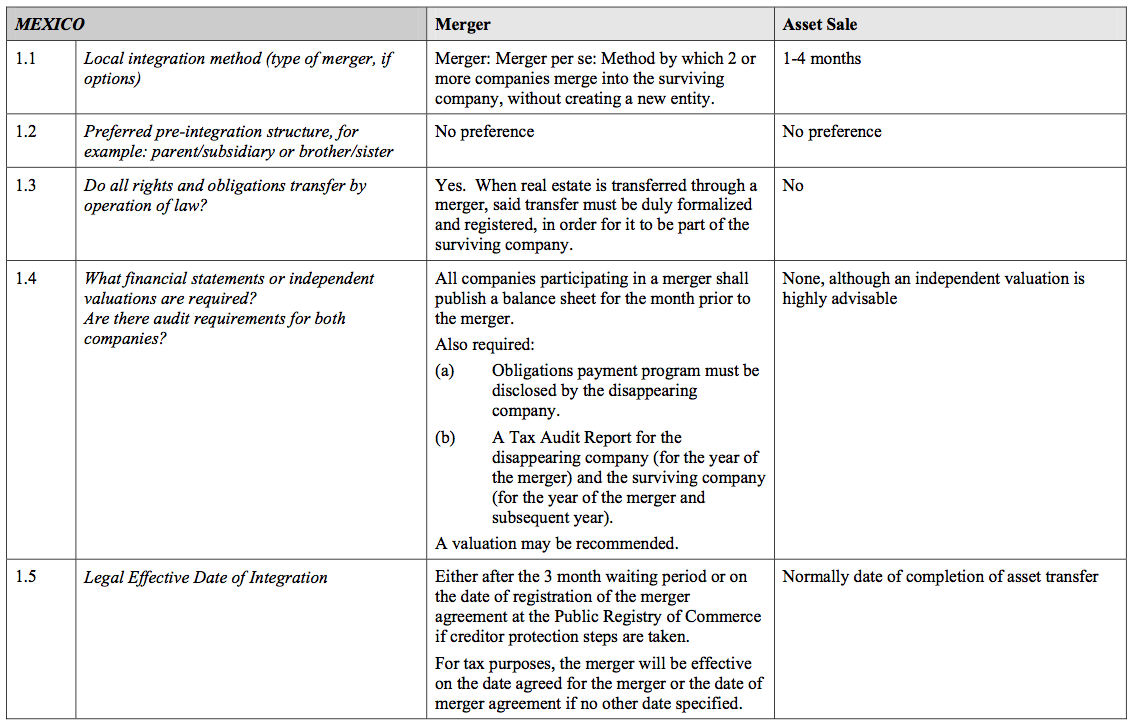

Mexico

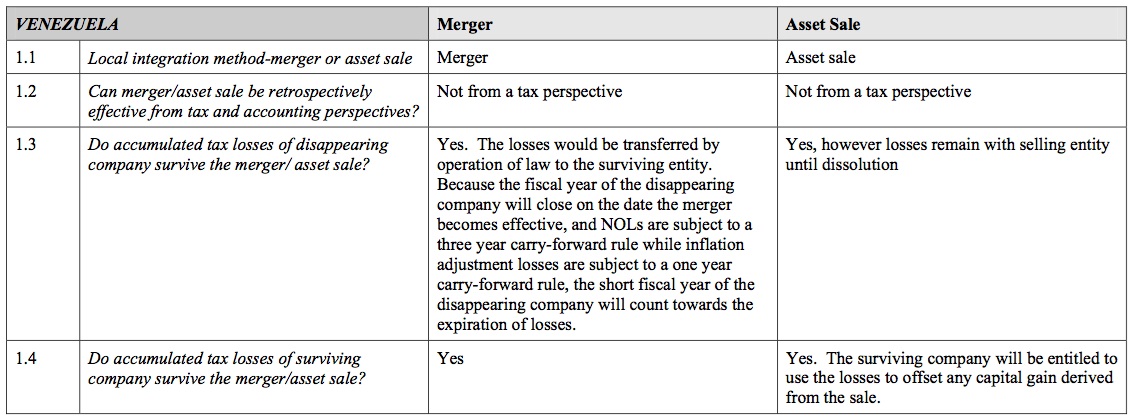

Venezuela

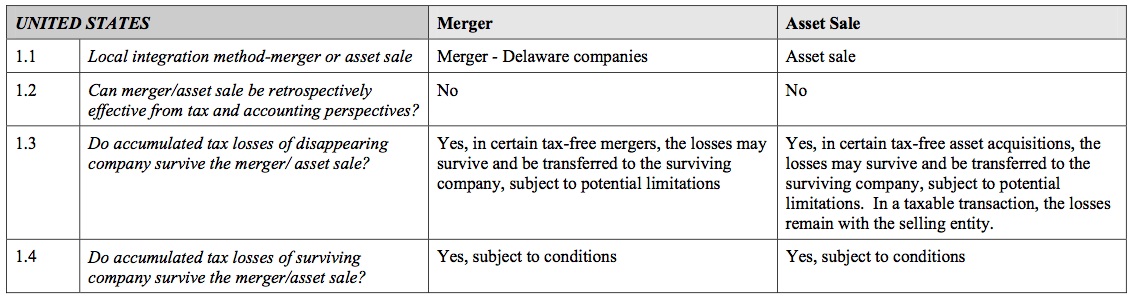

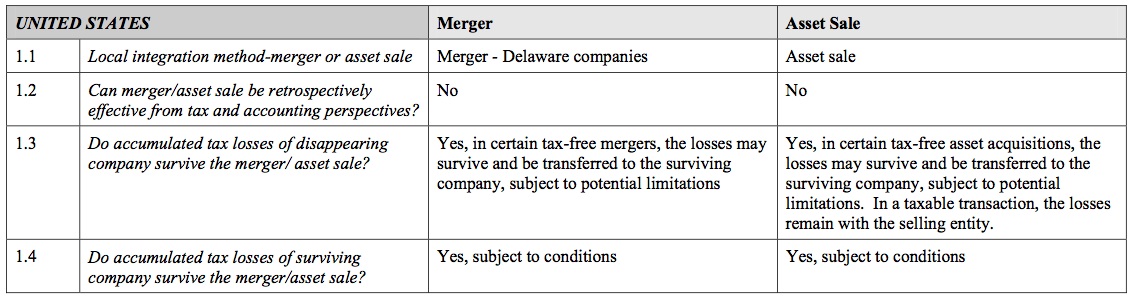

United States

2. ASIA PACIFIC REGION

Australia

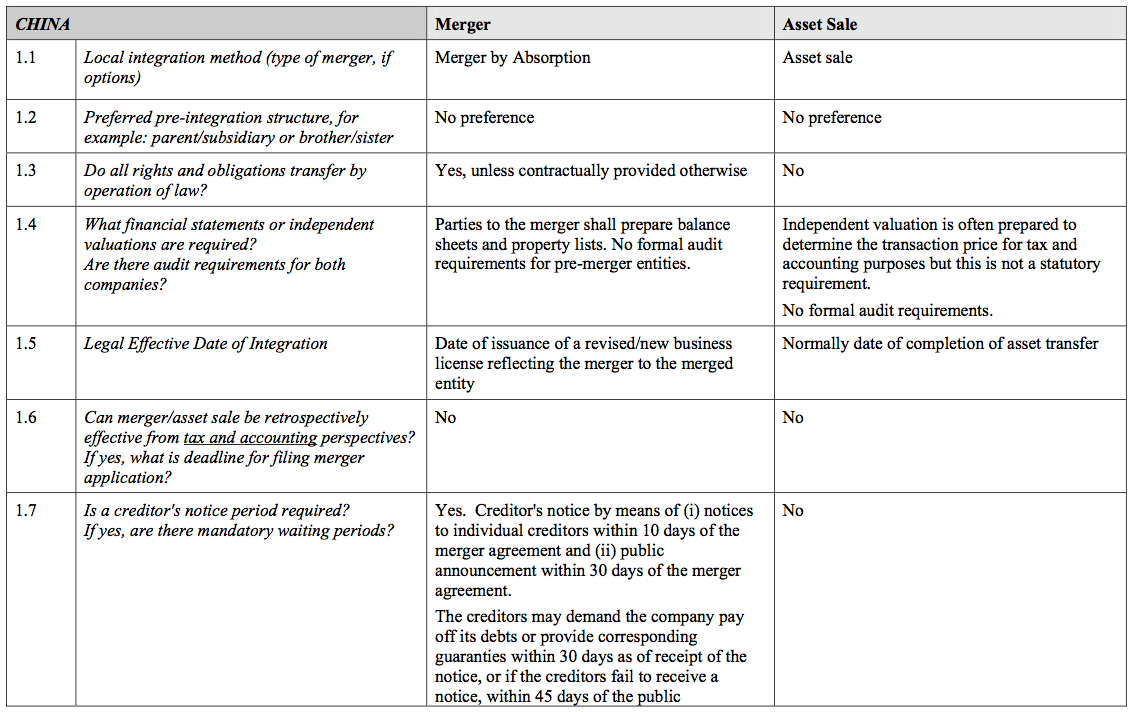

China

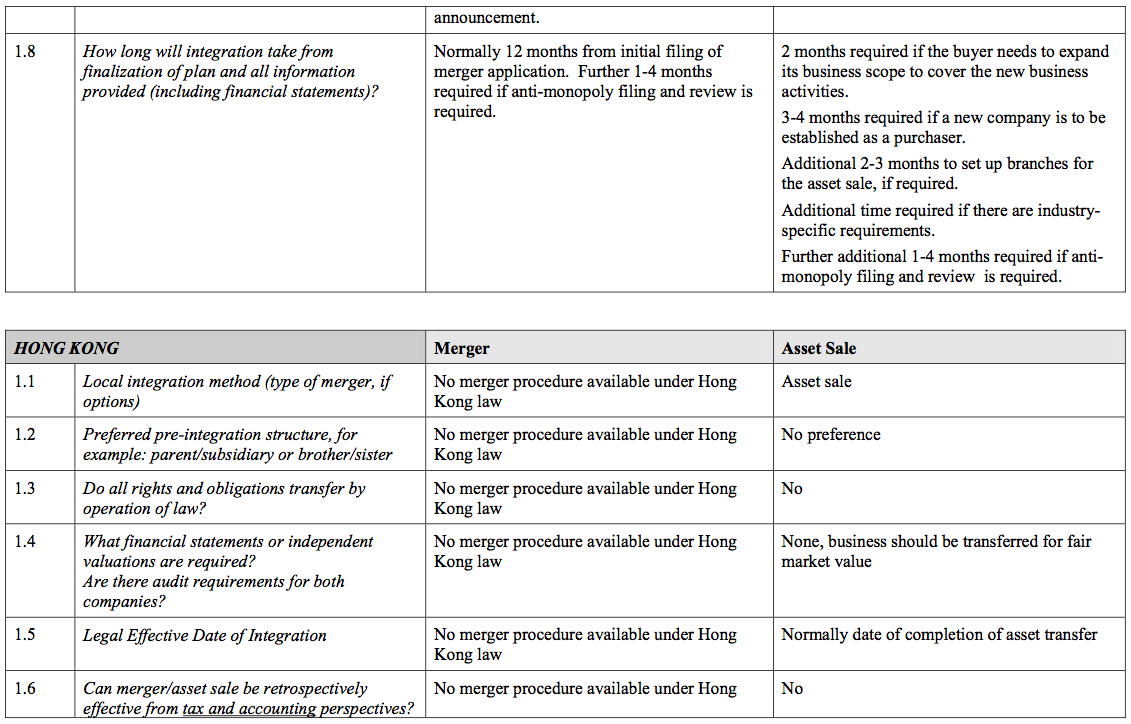

Hong Kong

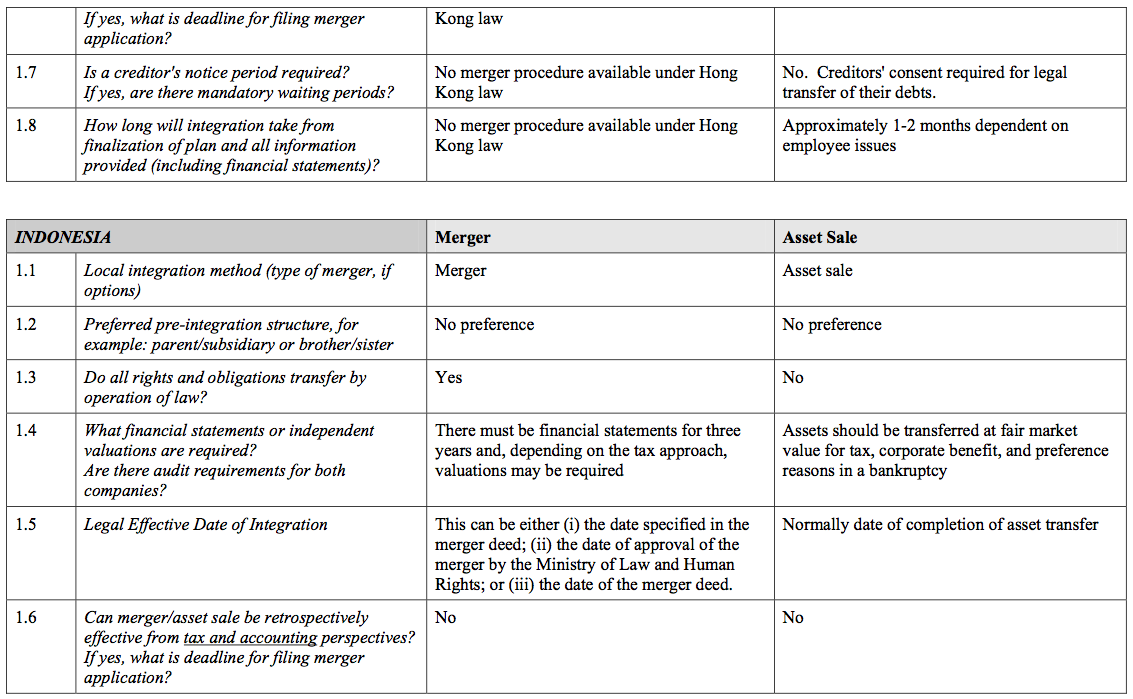

Indonesia

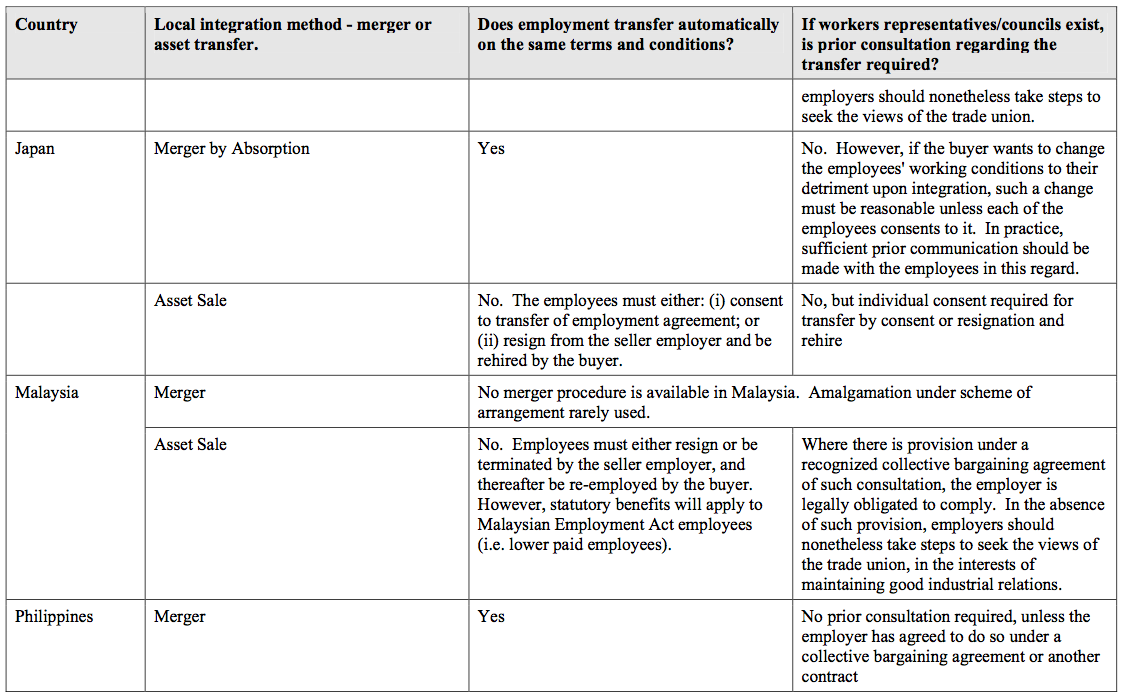

Japan

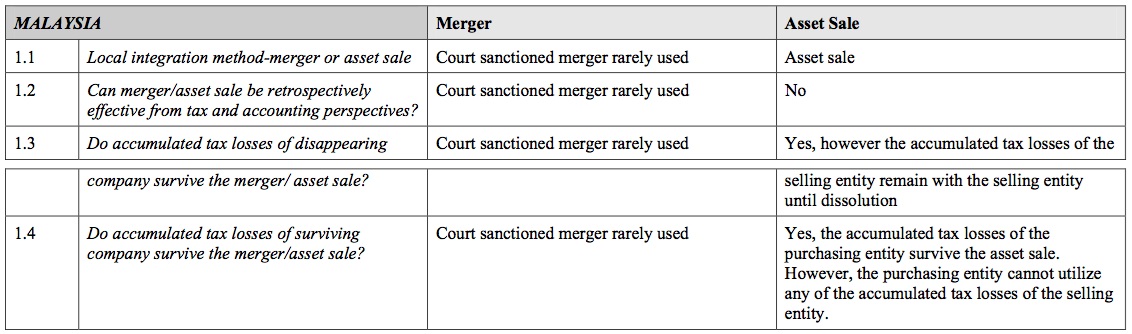

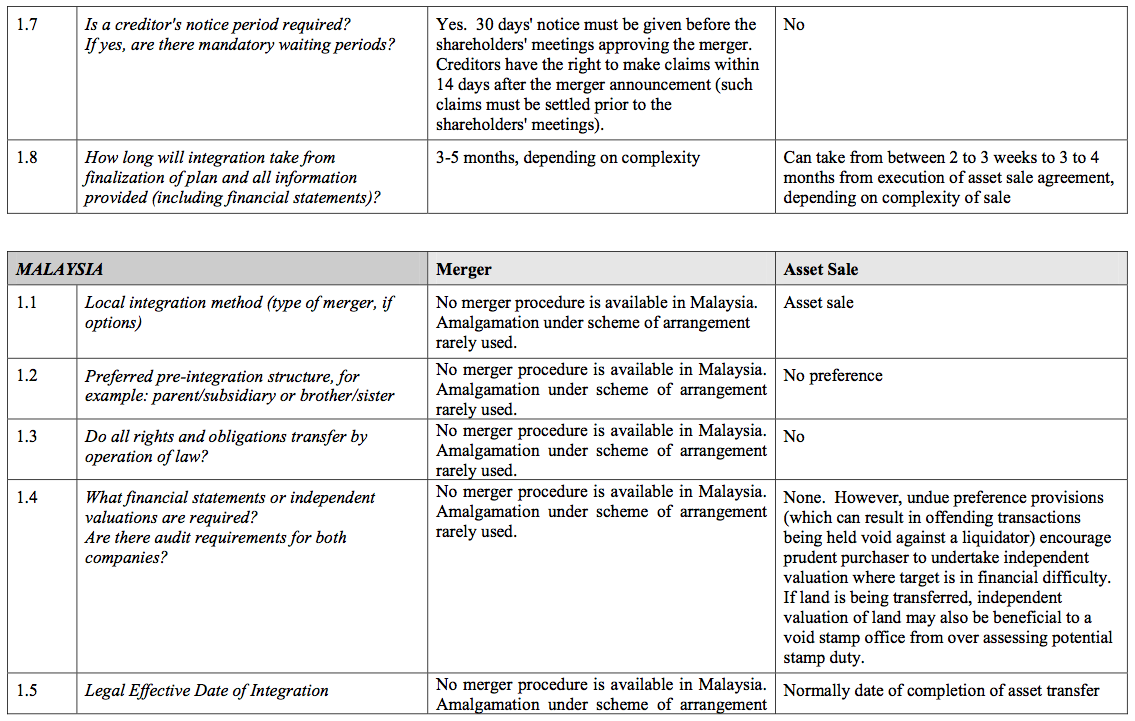

Malaysia

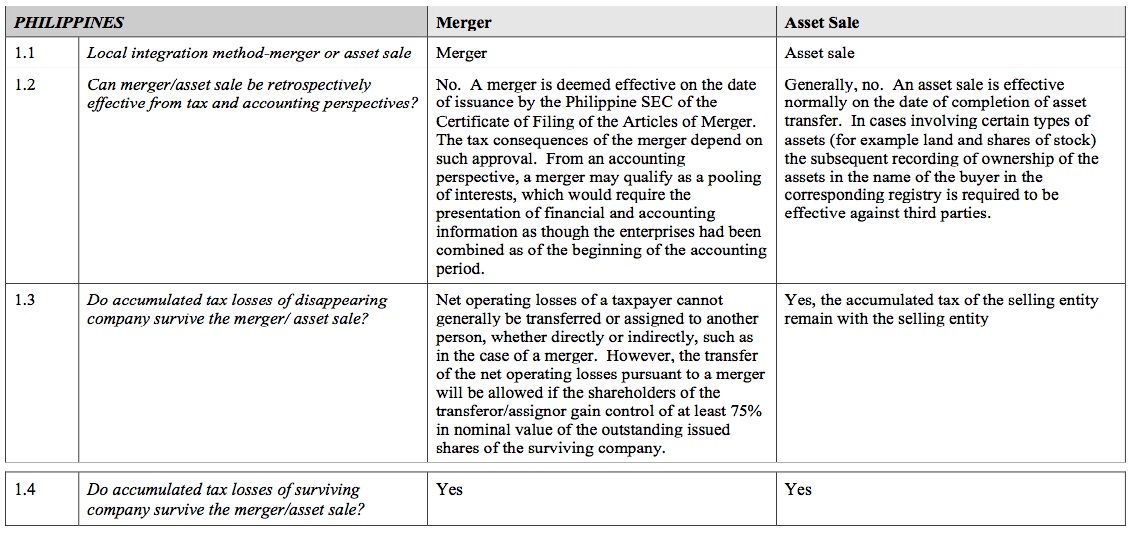

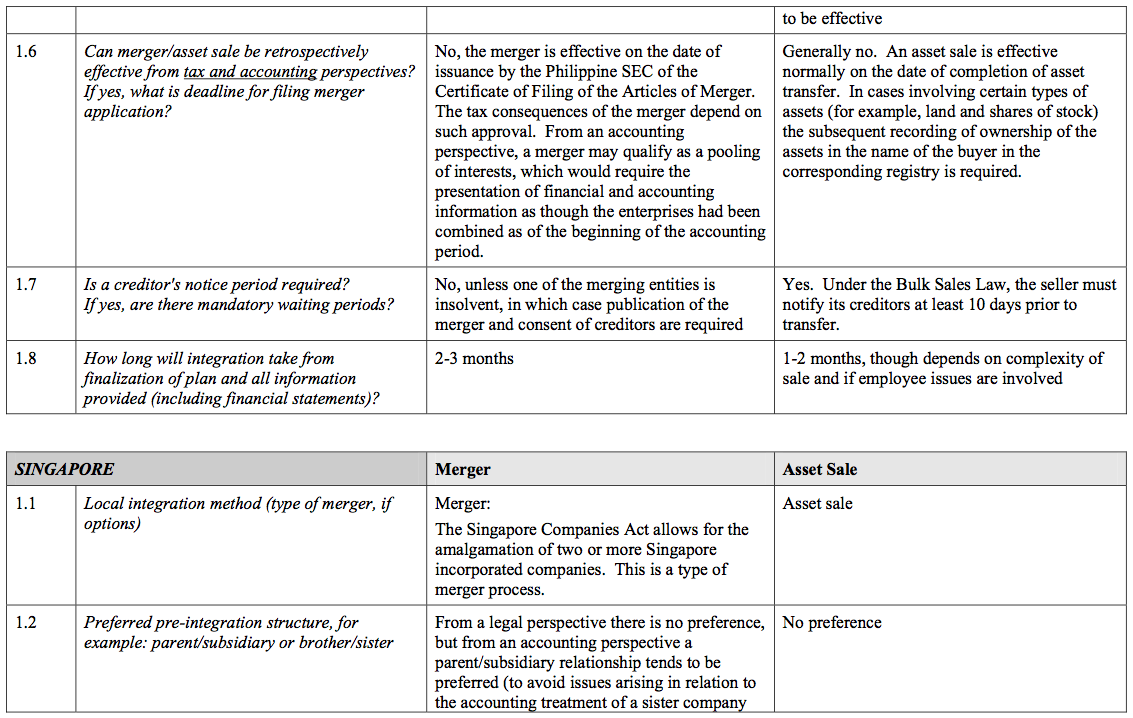

Philippines

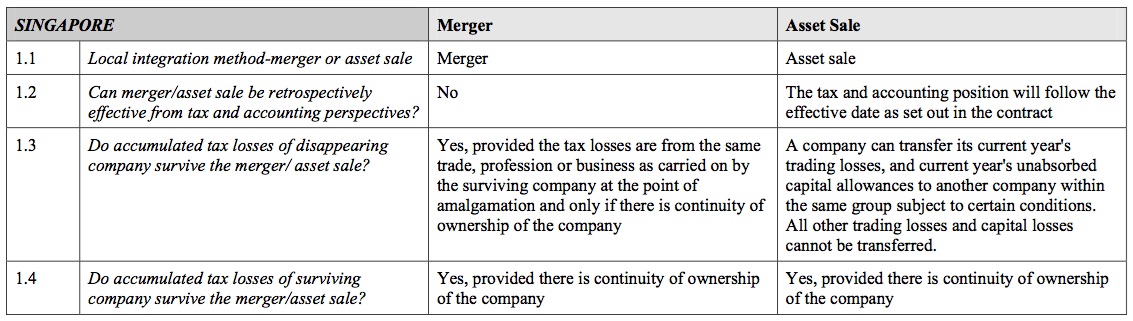

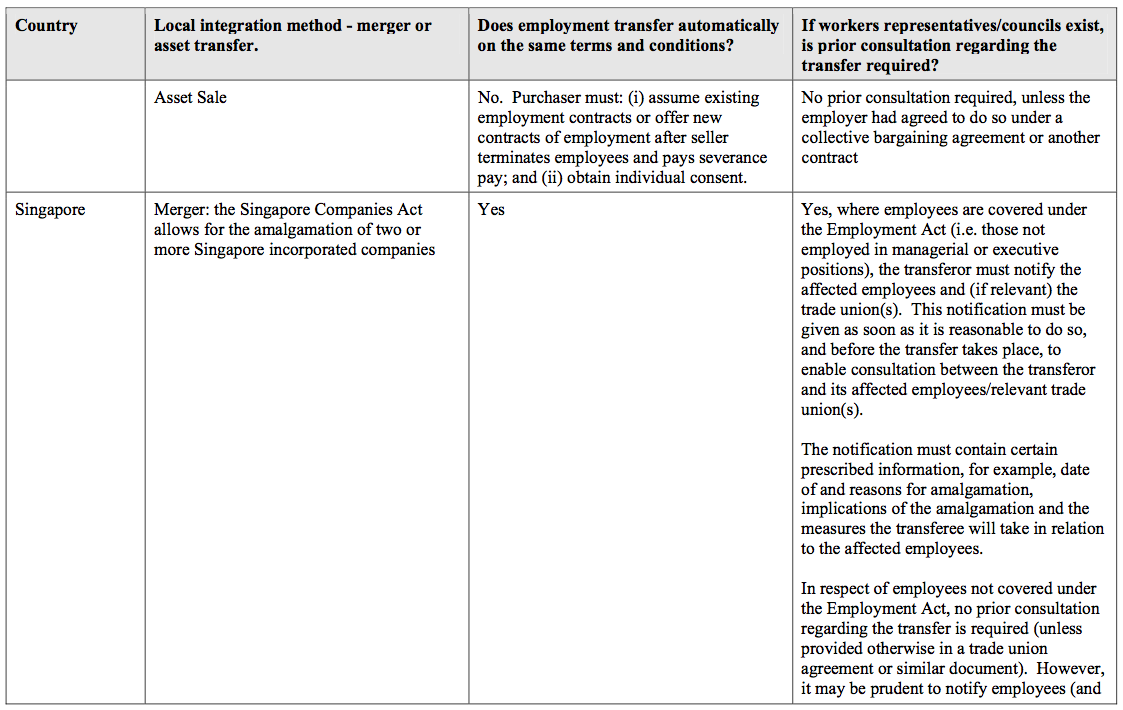

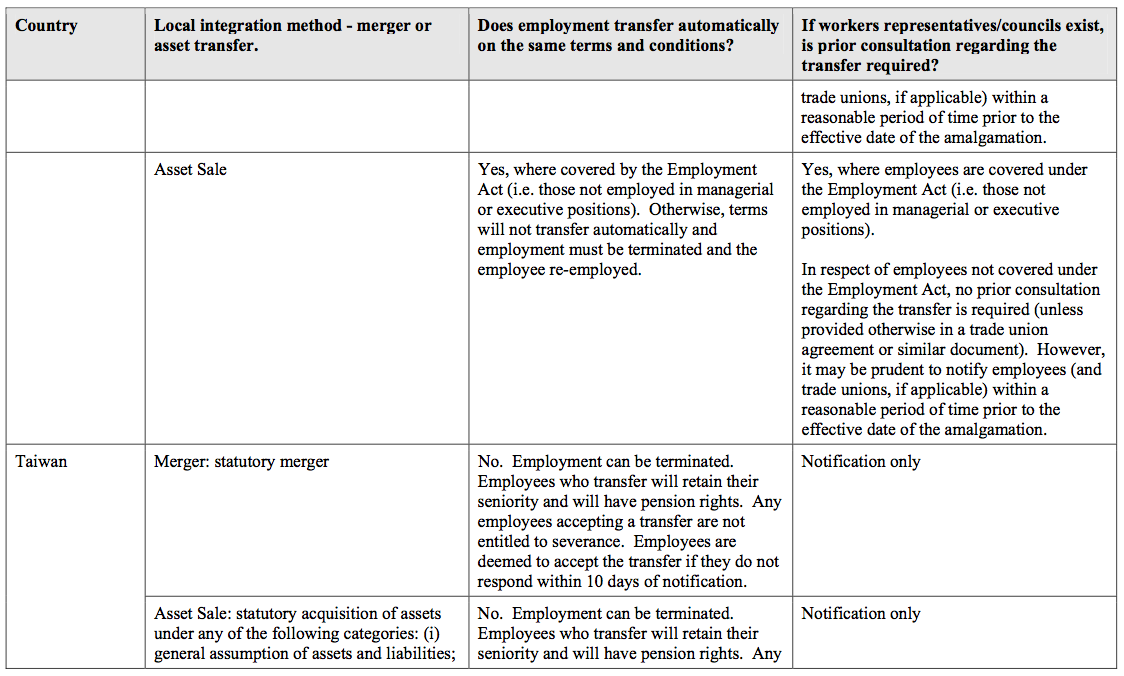

Singapore

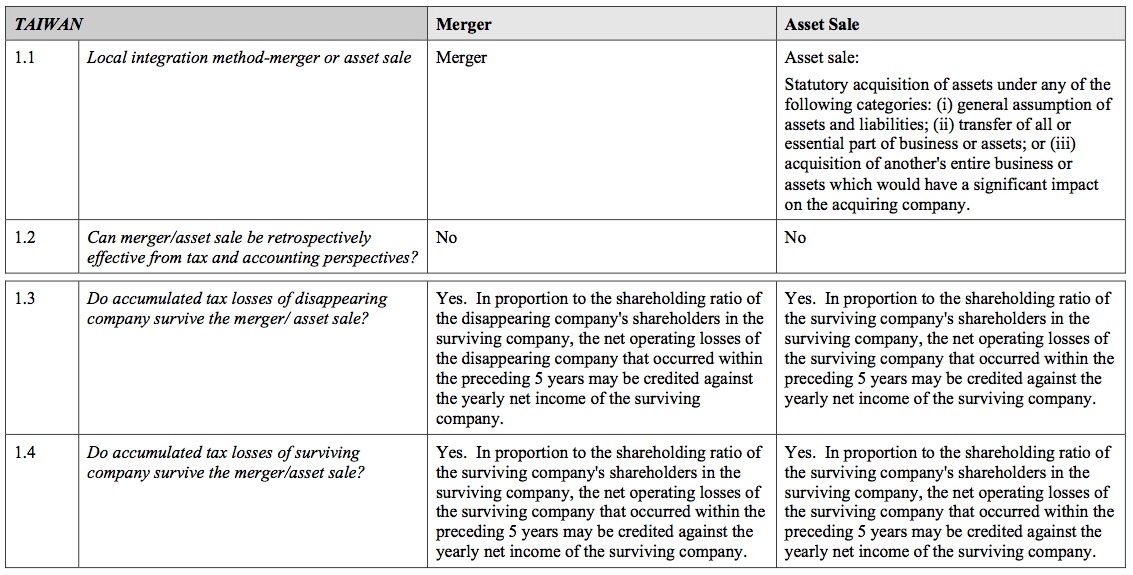

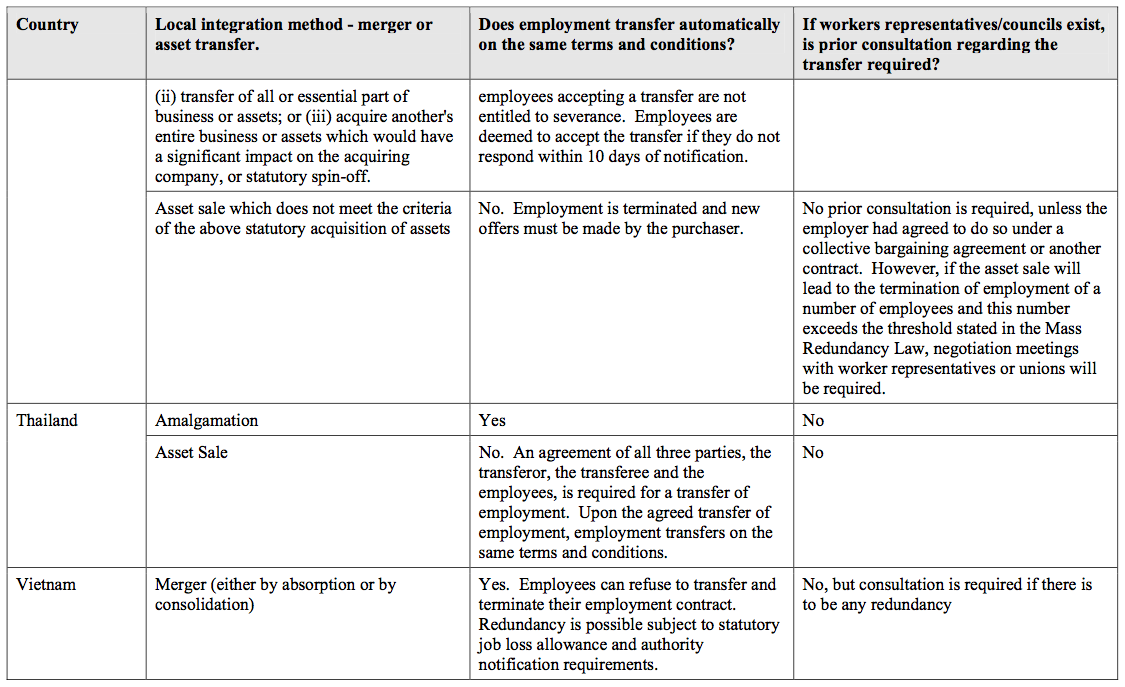

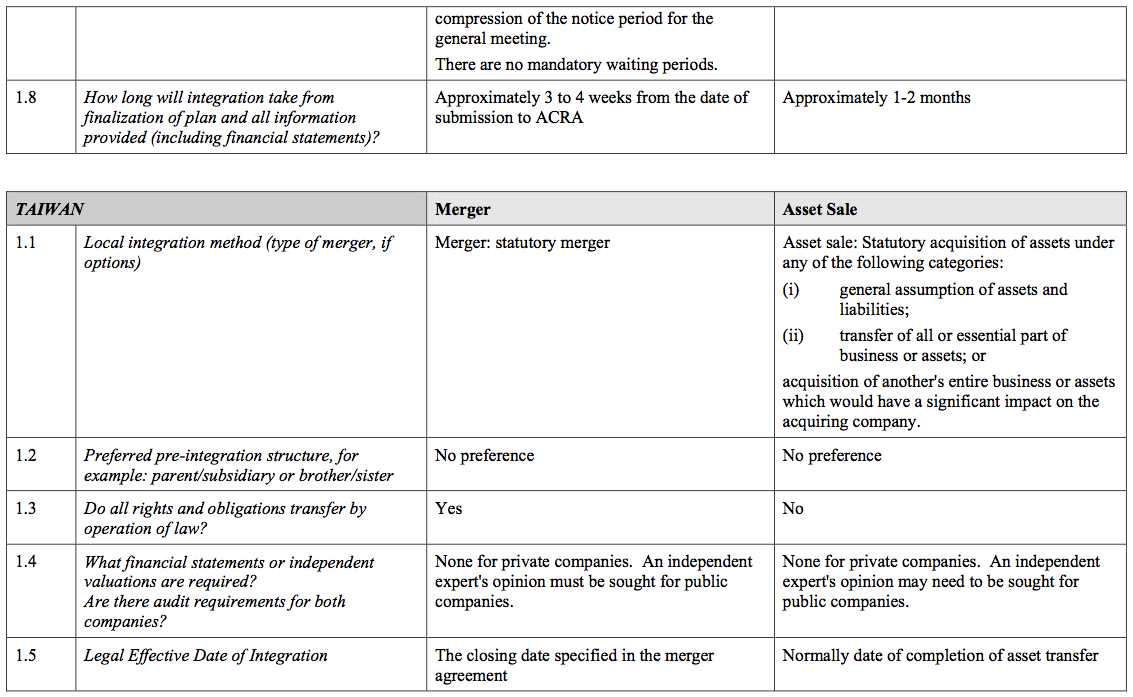

Taiwan

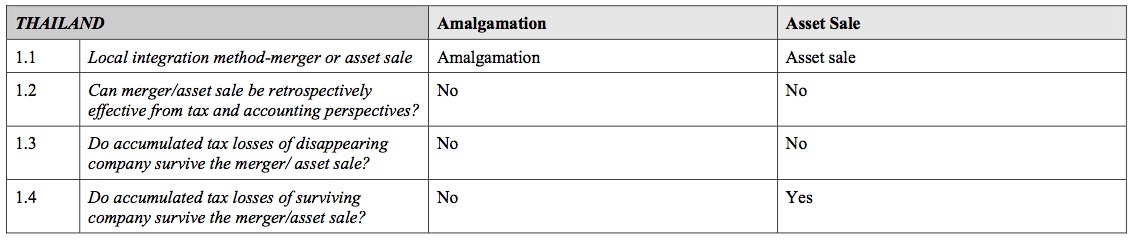

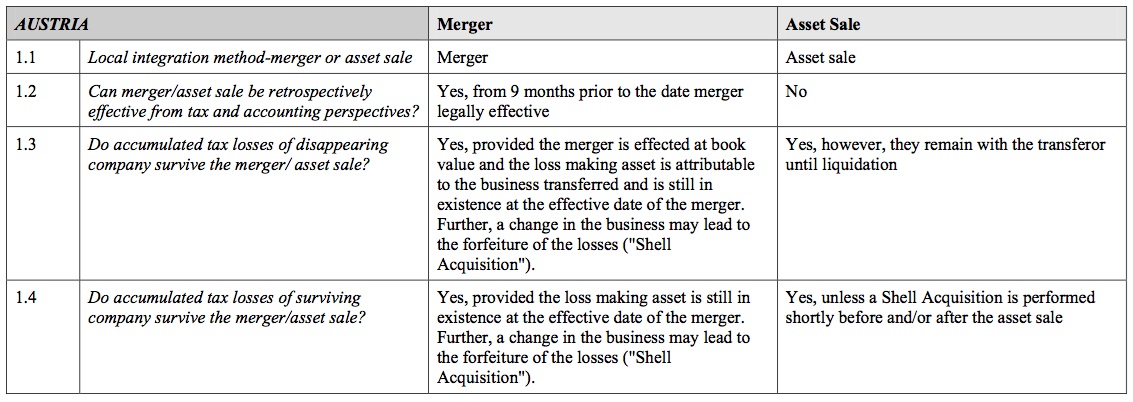

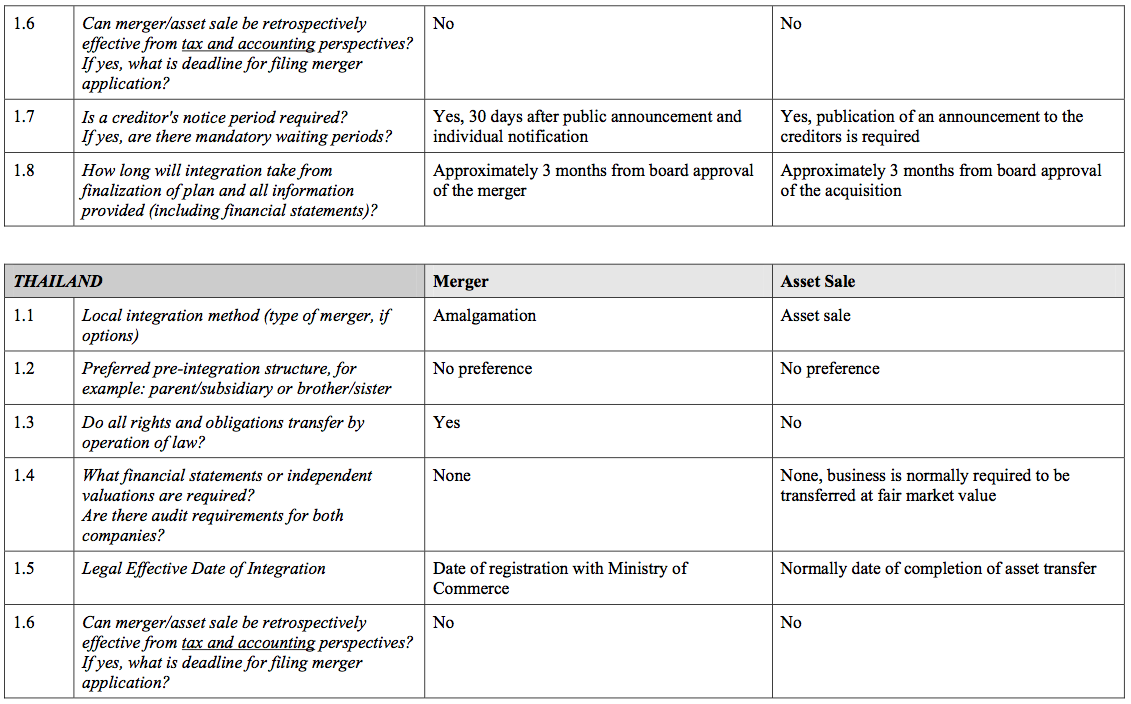

Thailand

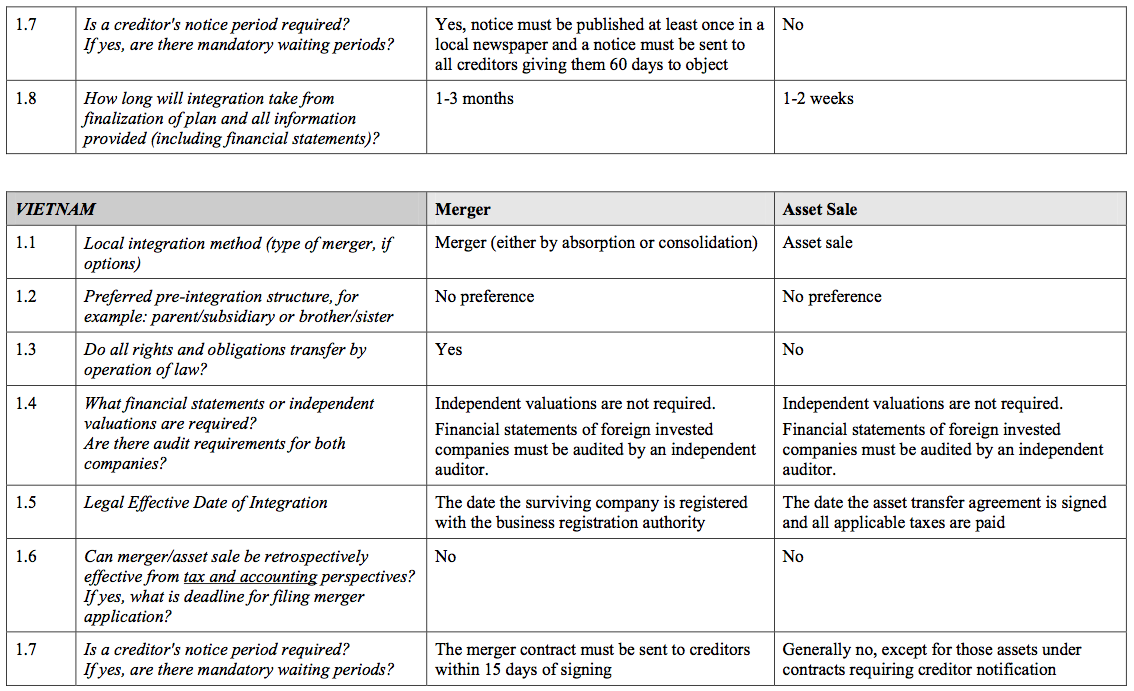

Vietnam

3. EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA

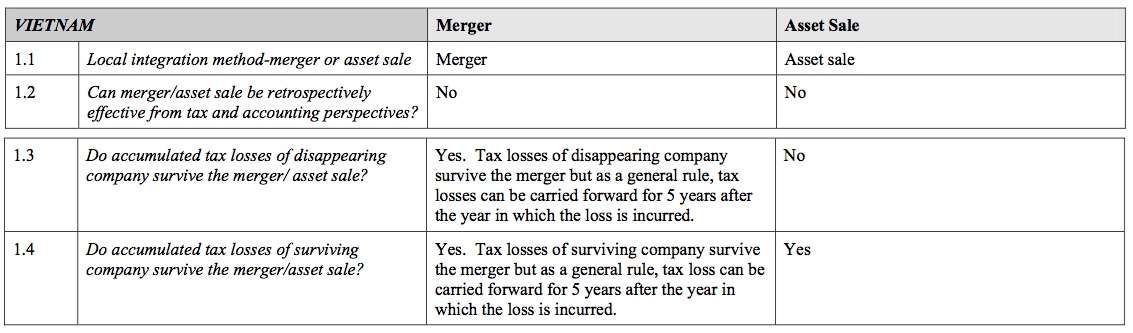

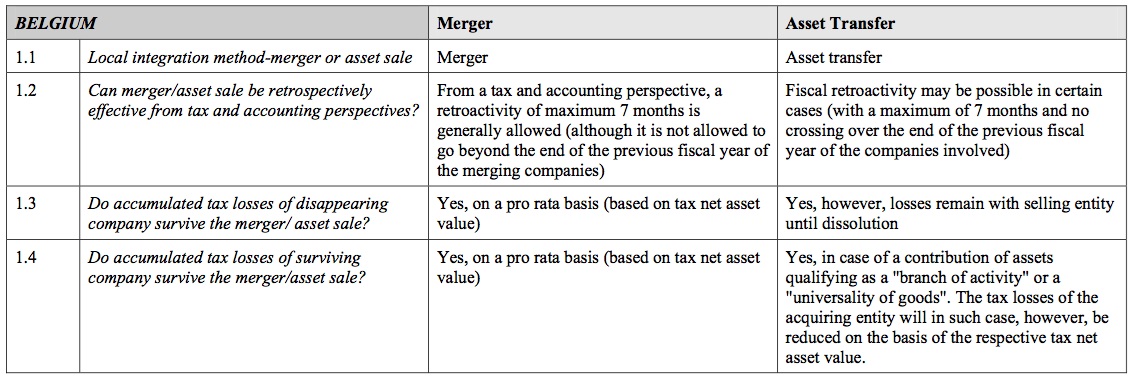

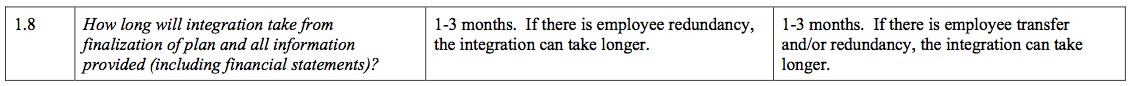

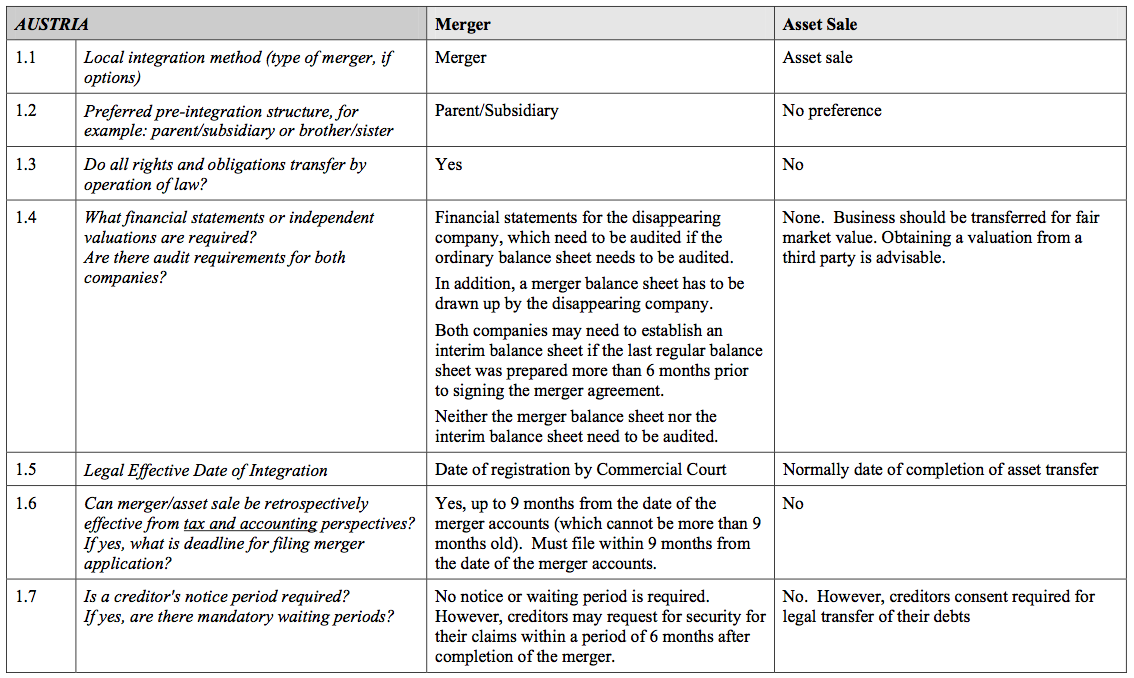

Austria

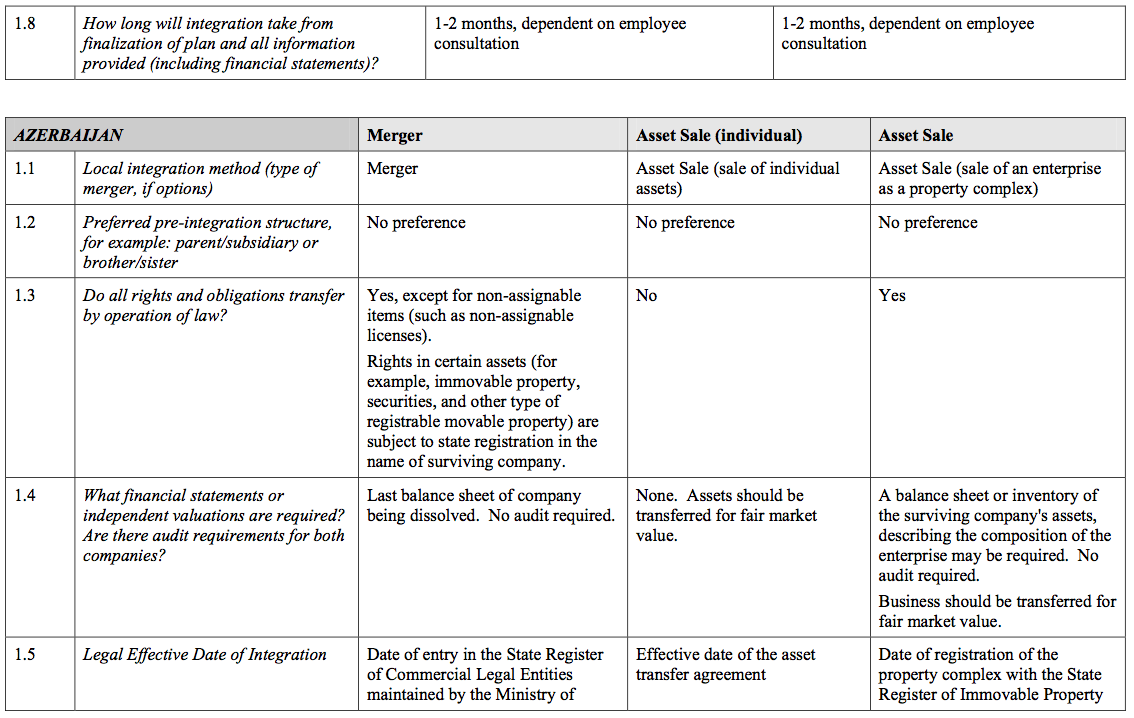

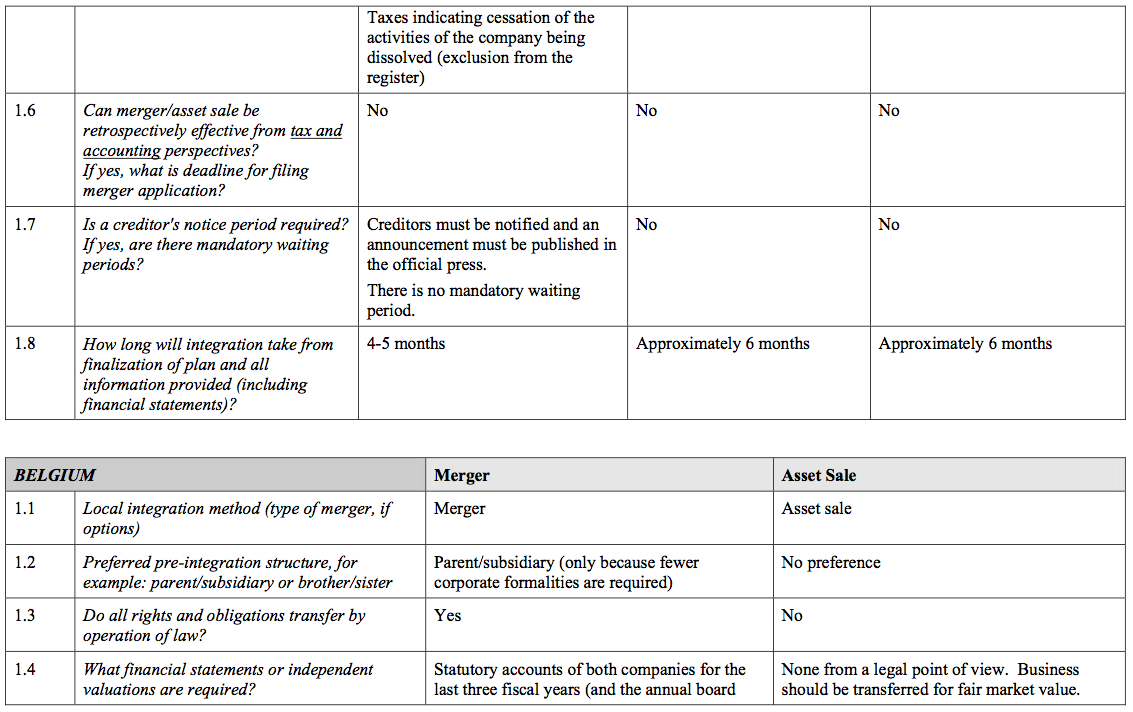

Azerbaijan

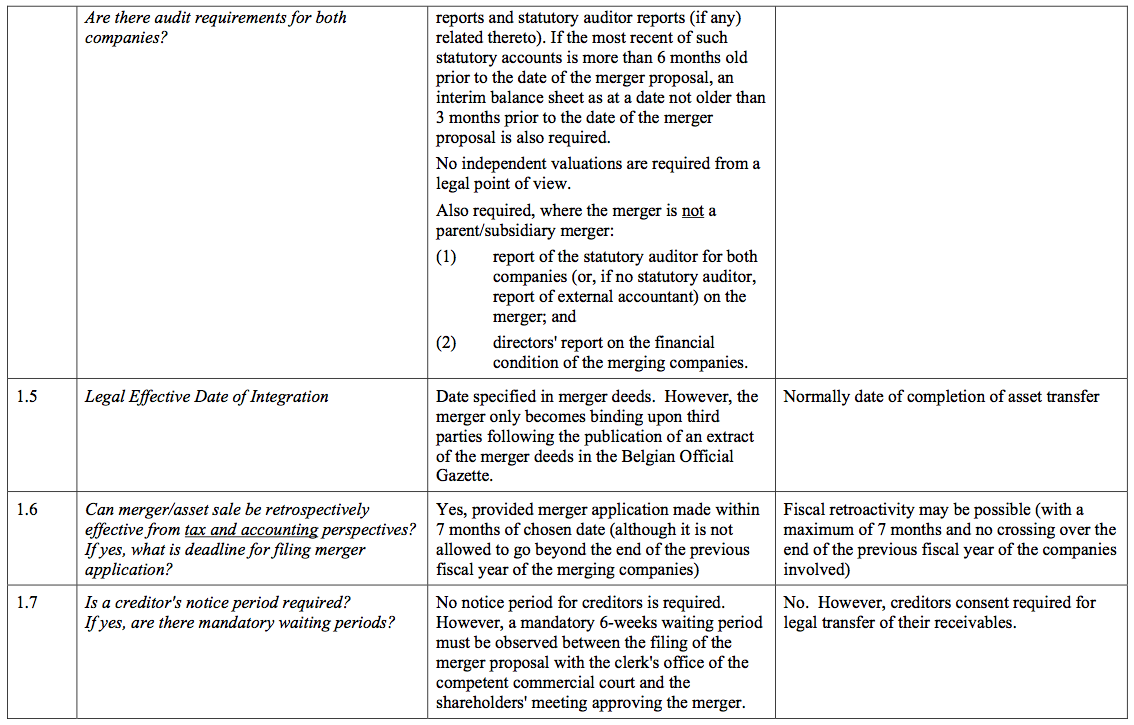

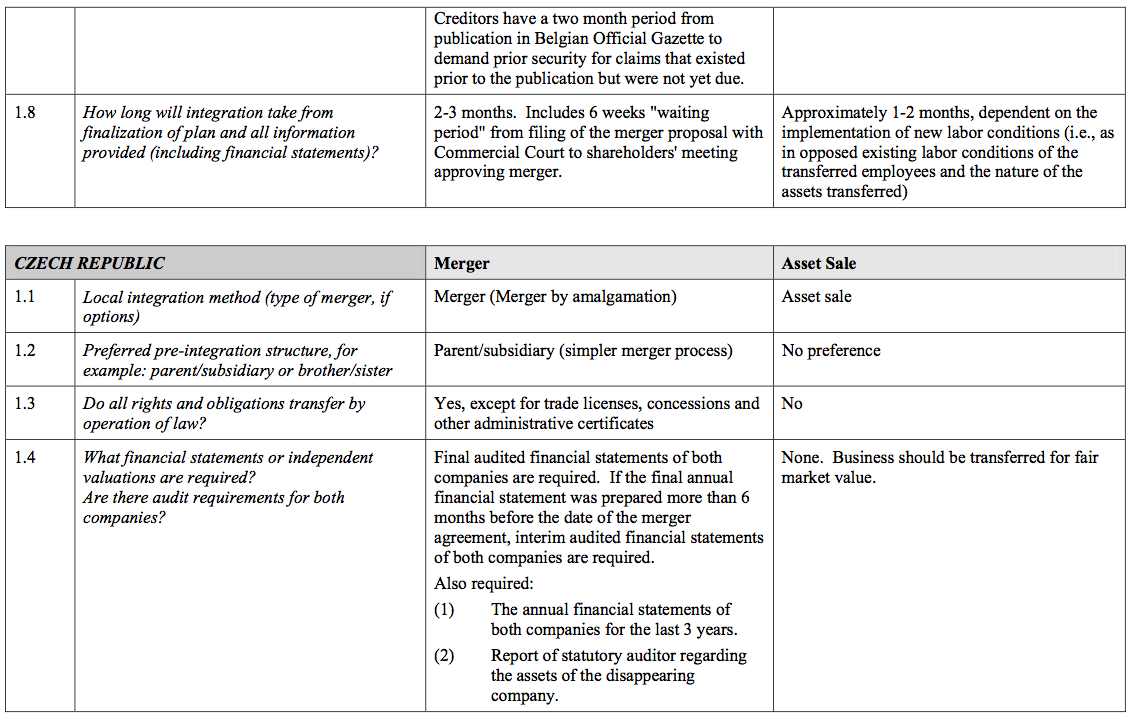

Belgium

Czech Republic

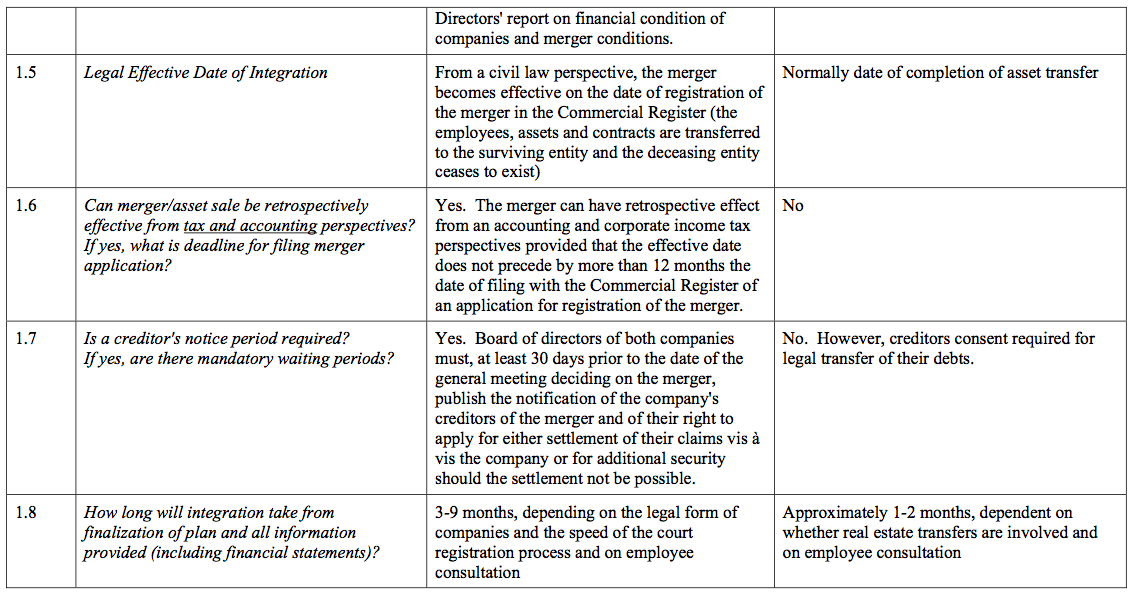

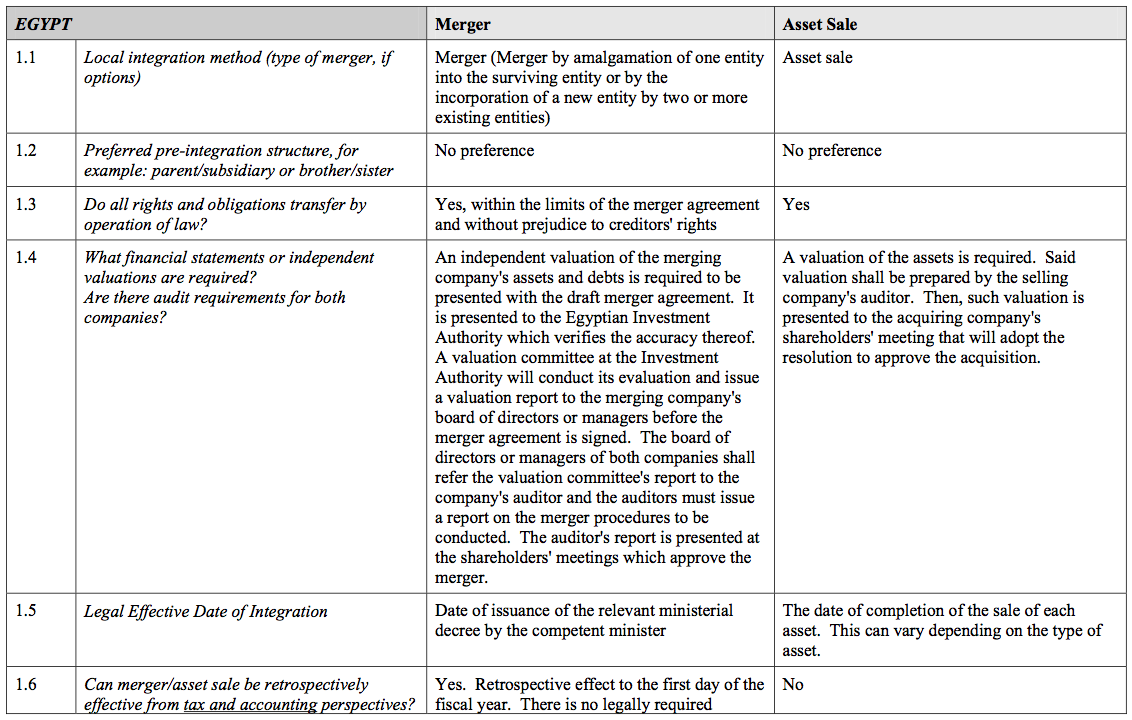

Egypt

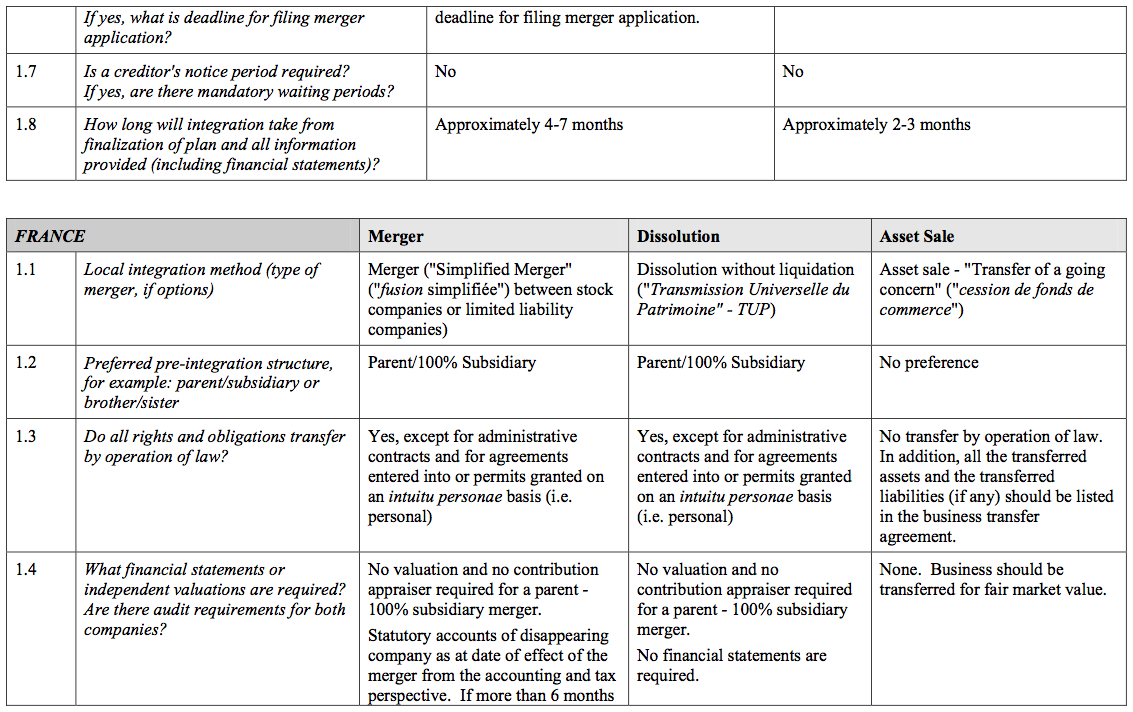

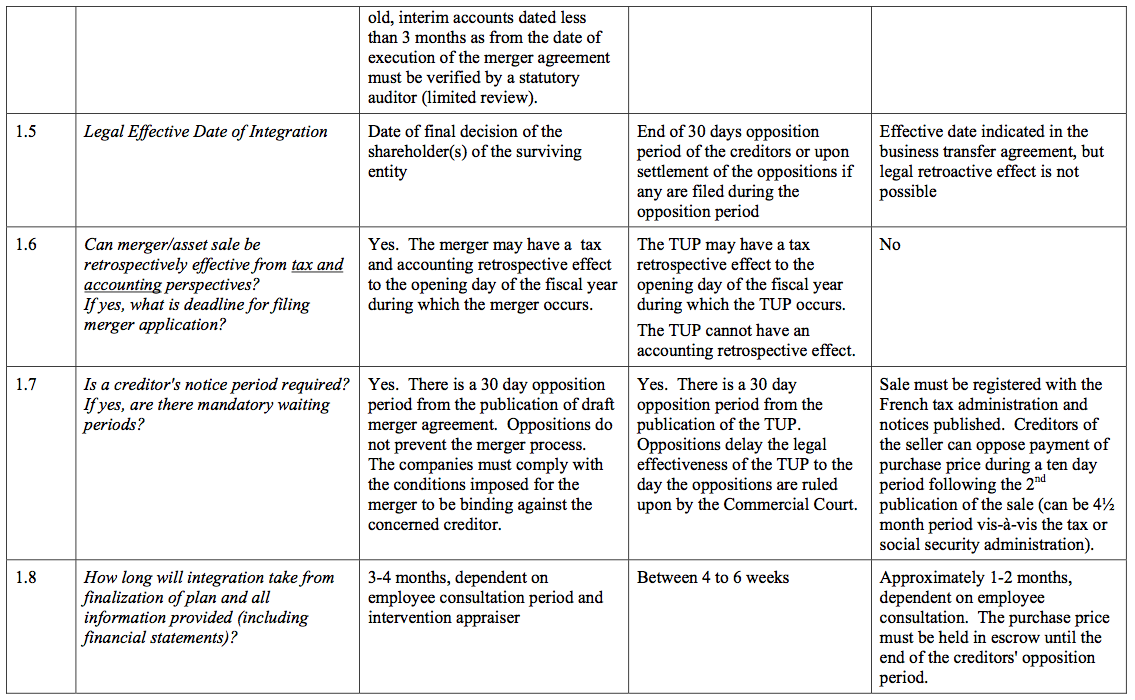

France

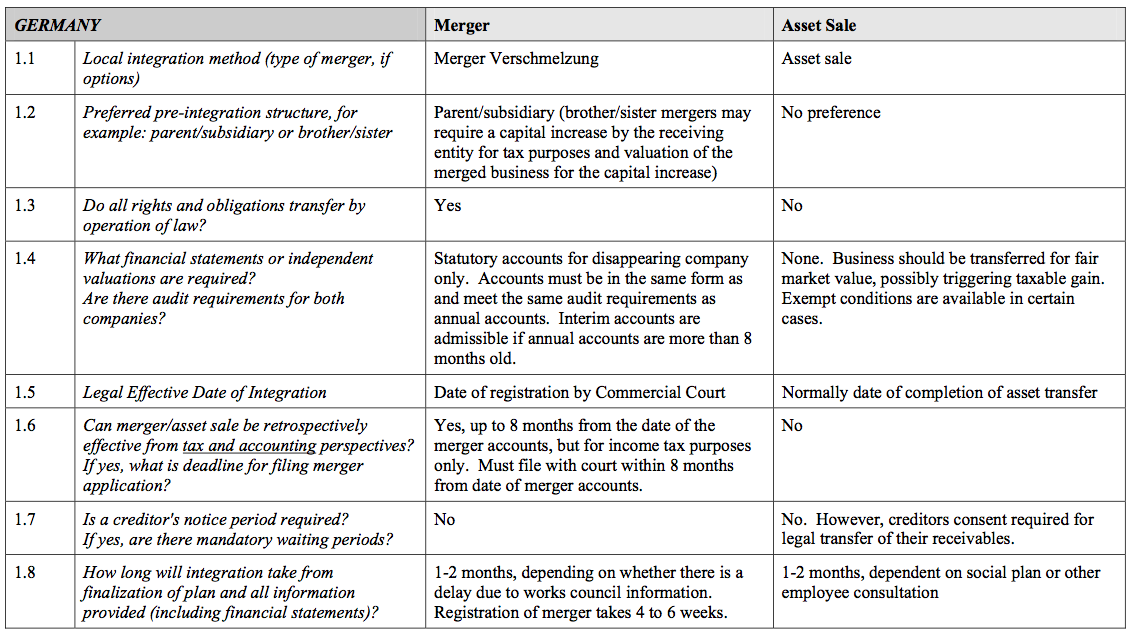

Germany

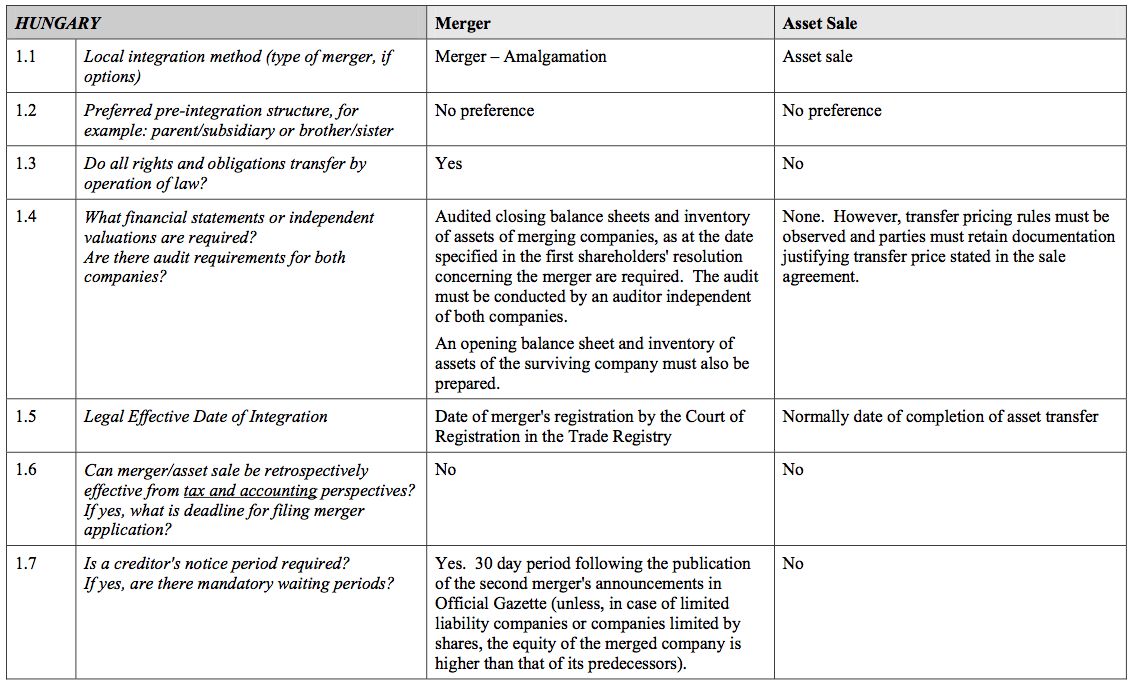

Hungary

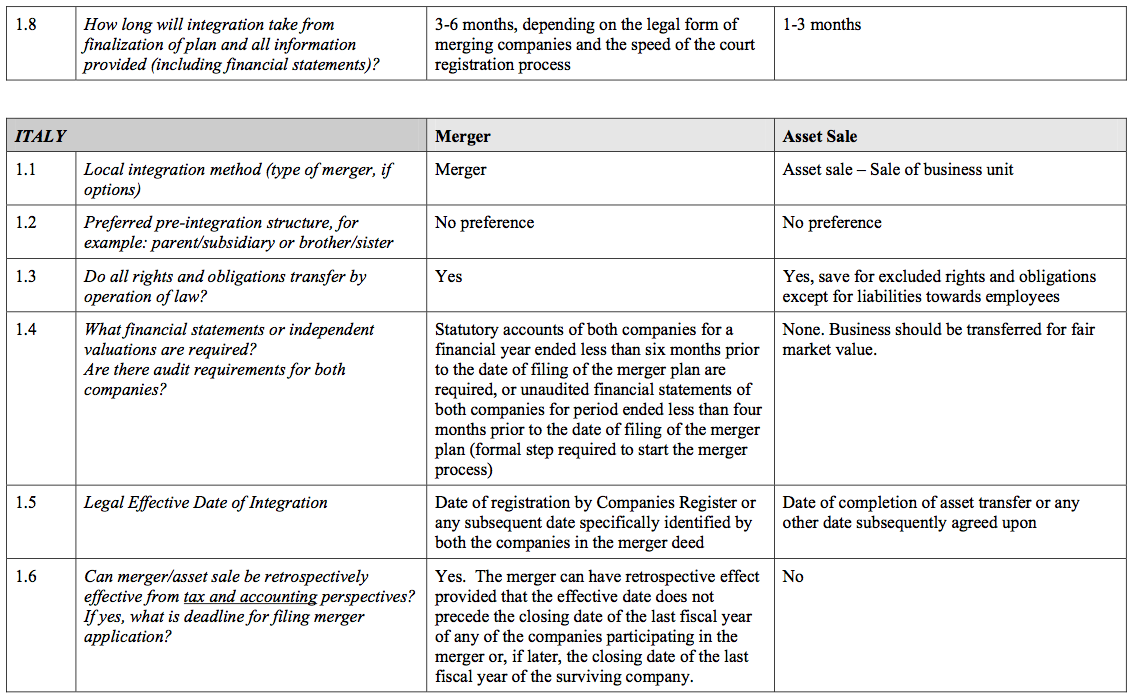

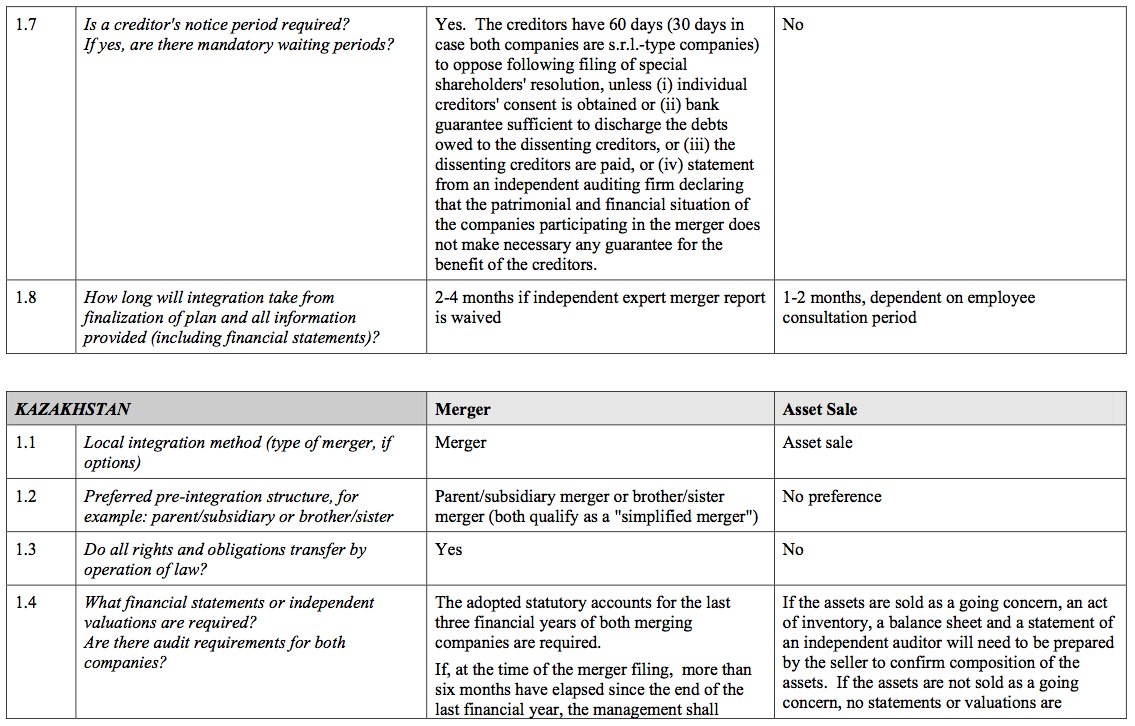

Italy

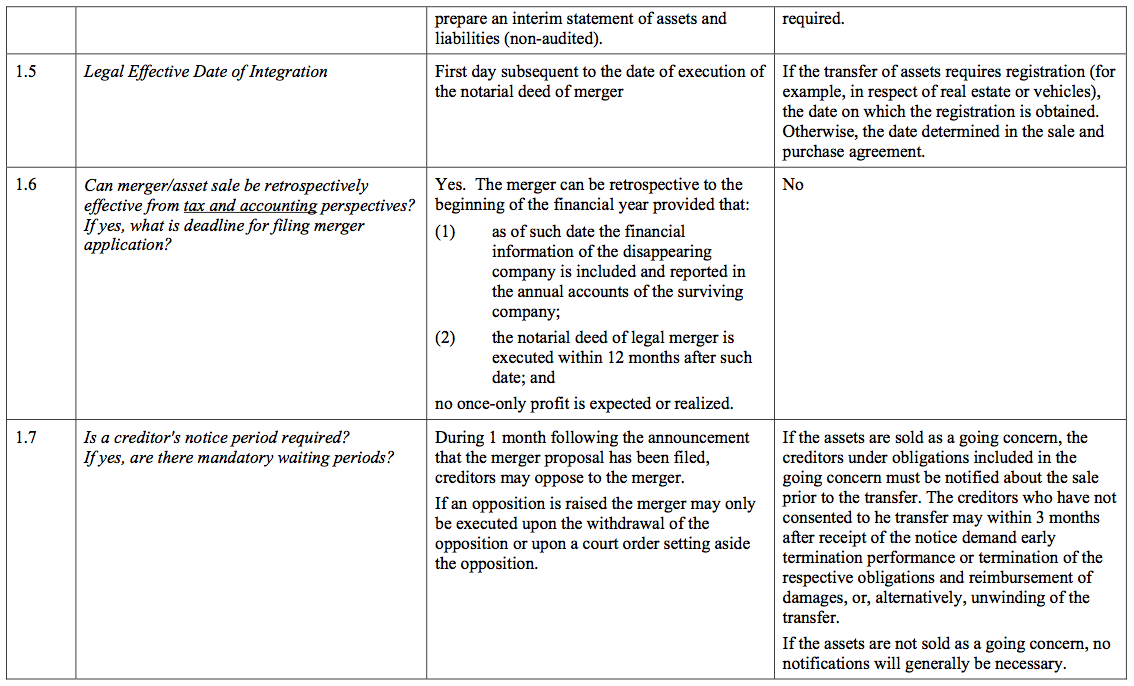

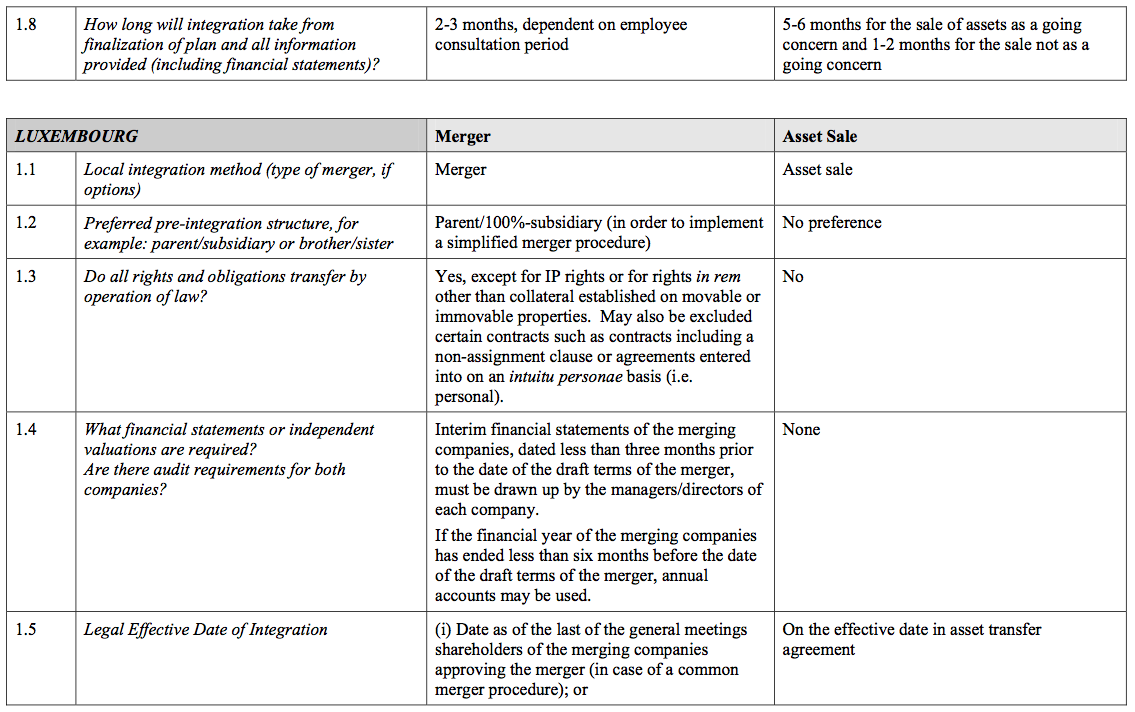

Kazakhstan

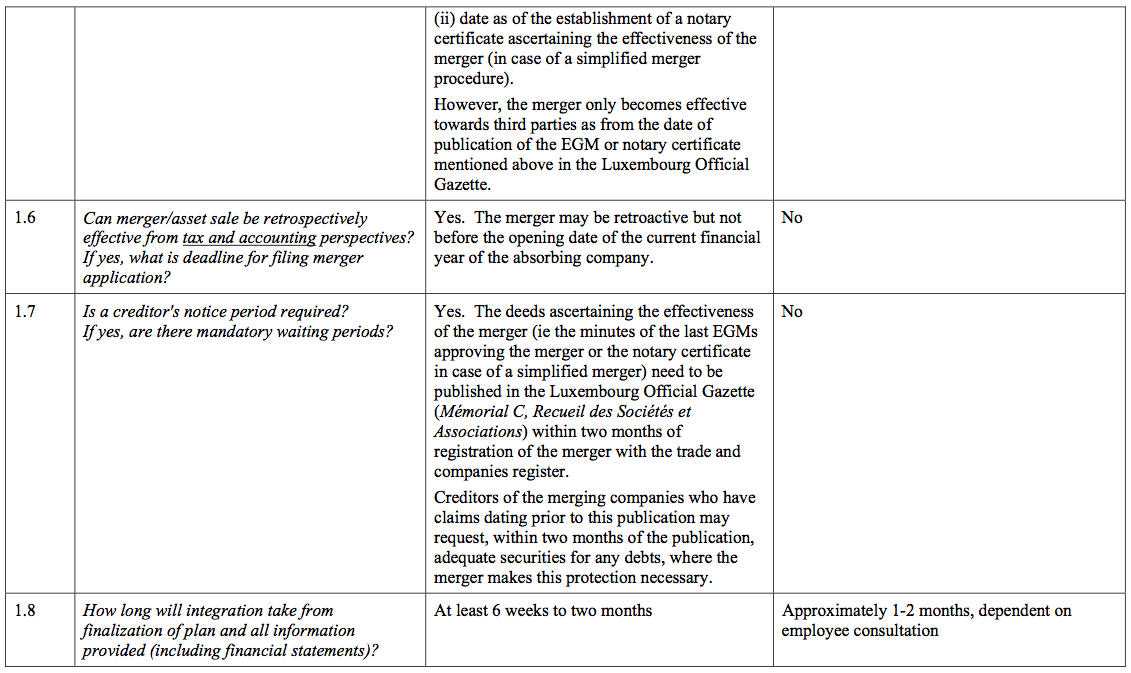

Luxembourg

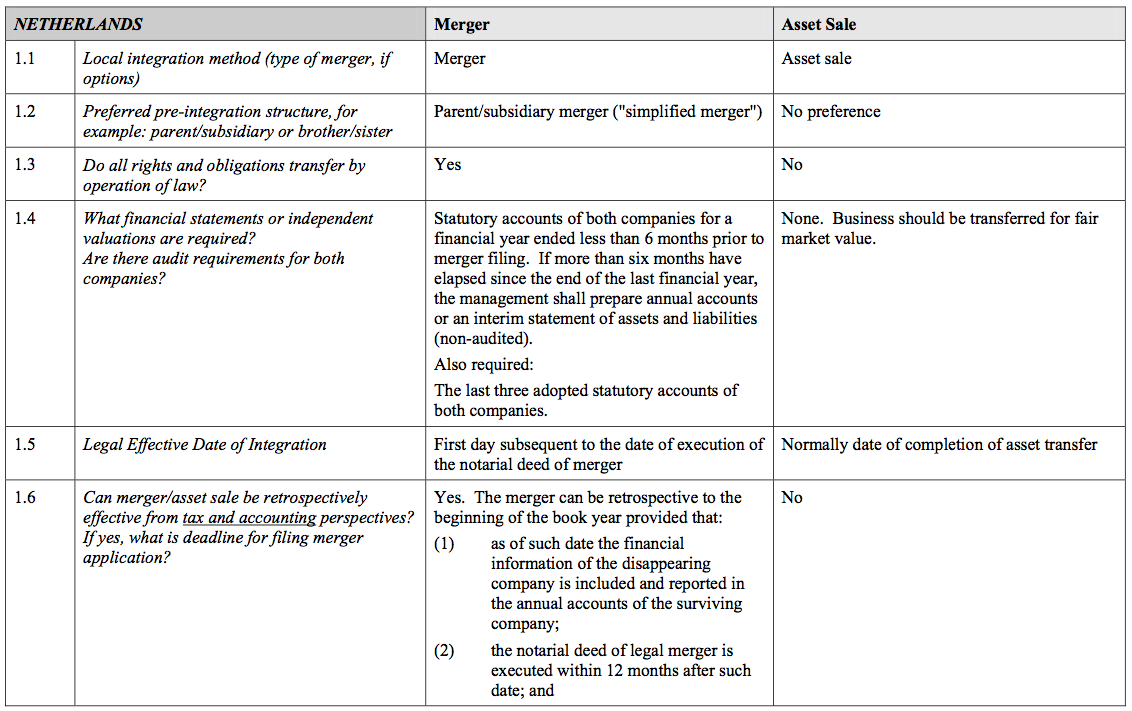

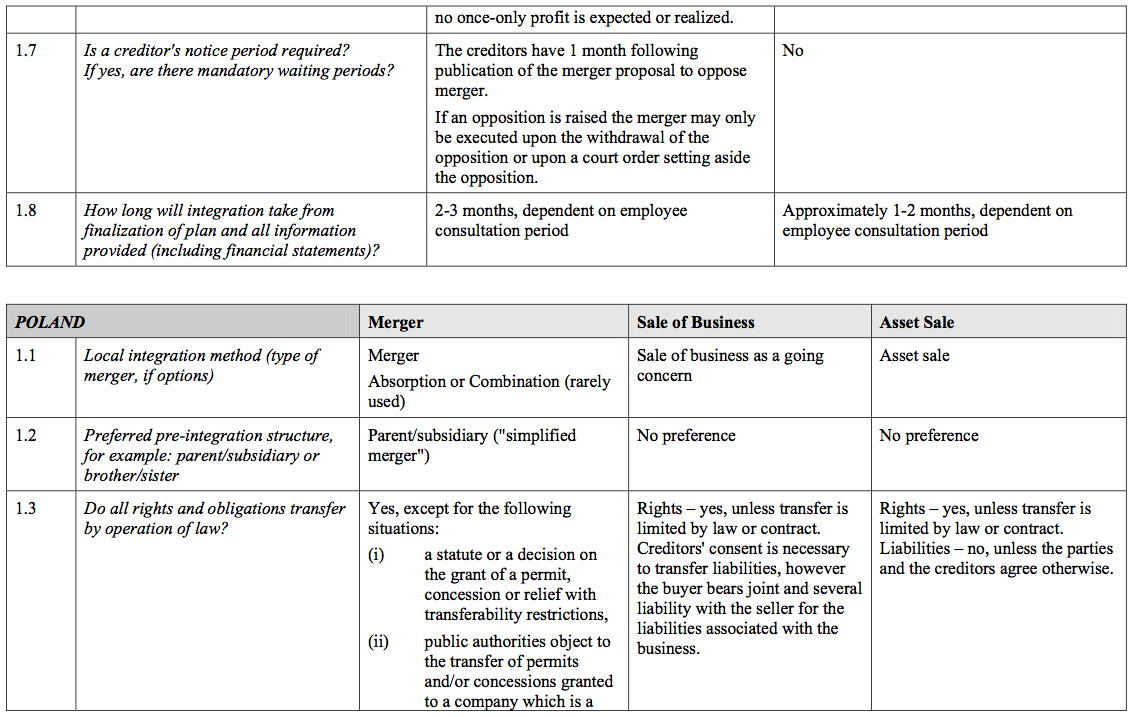

Netherlands

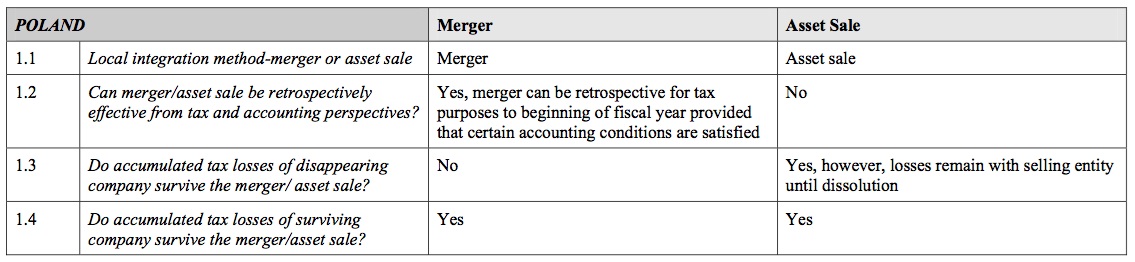

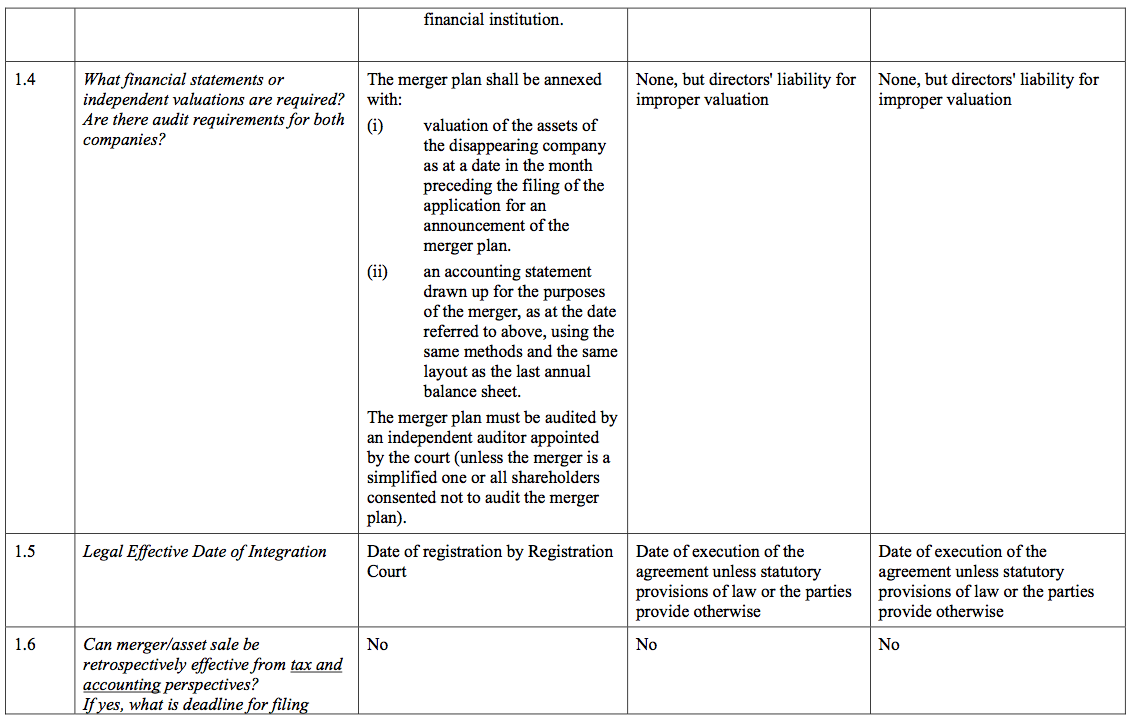

Poland

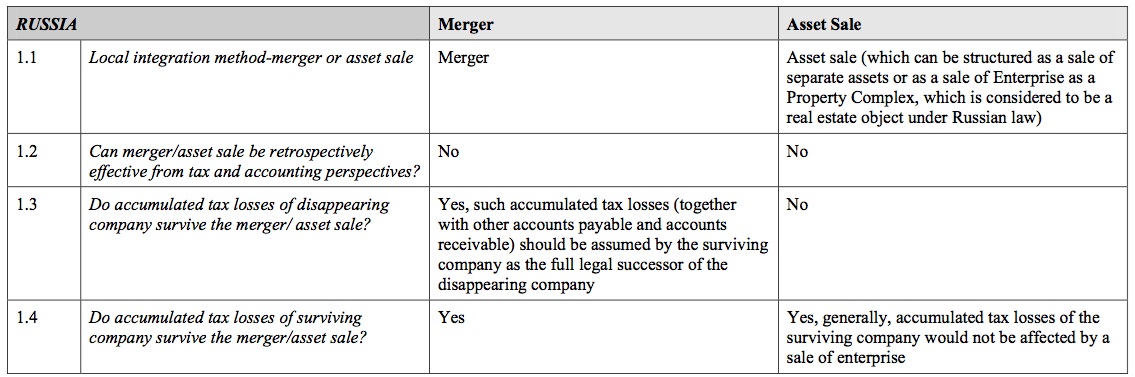

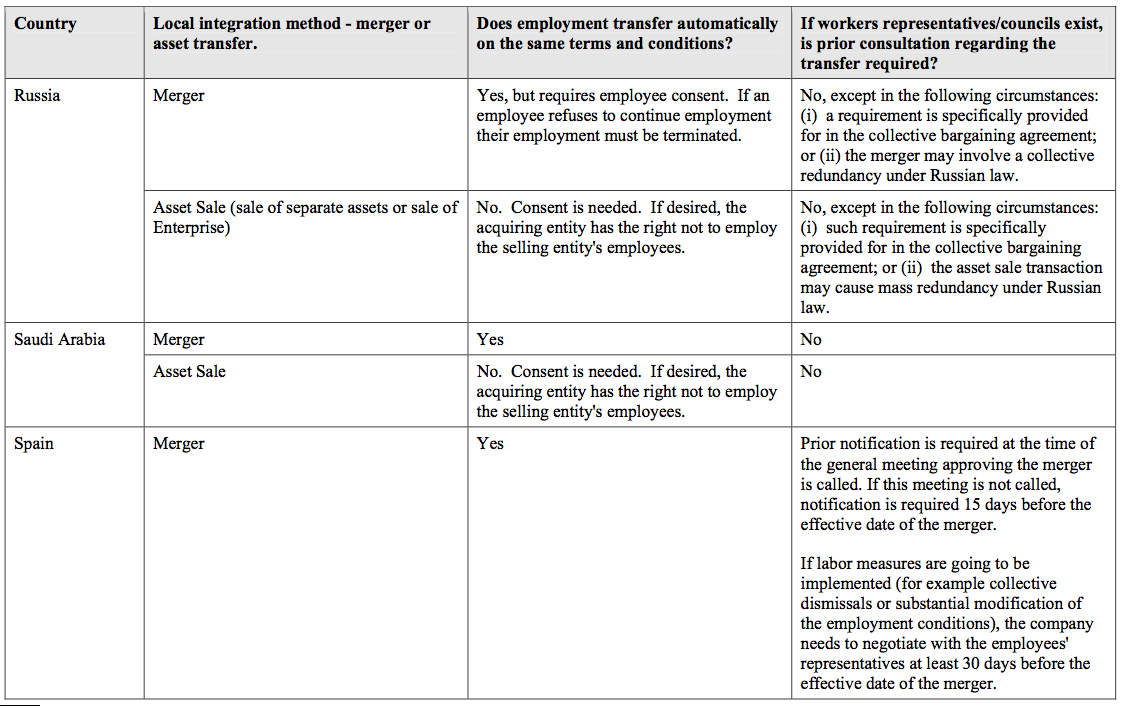

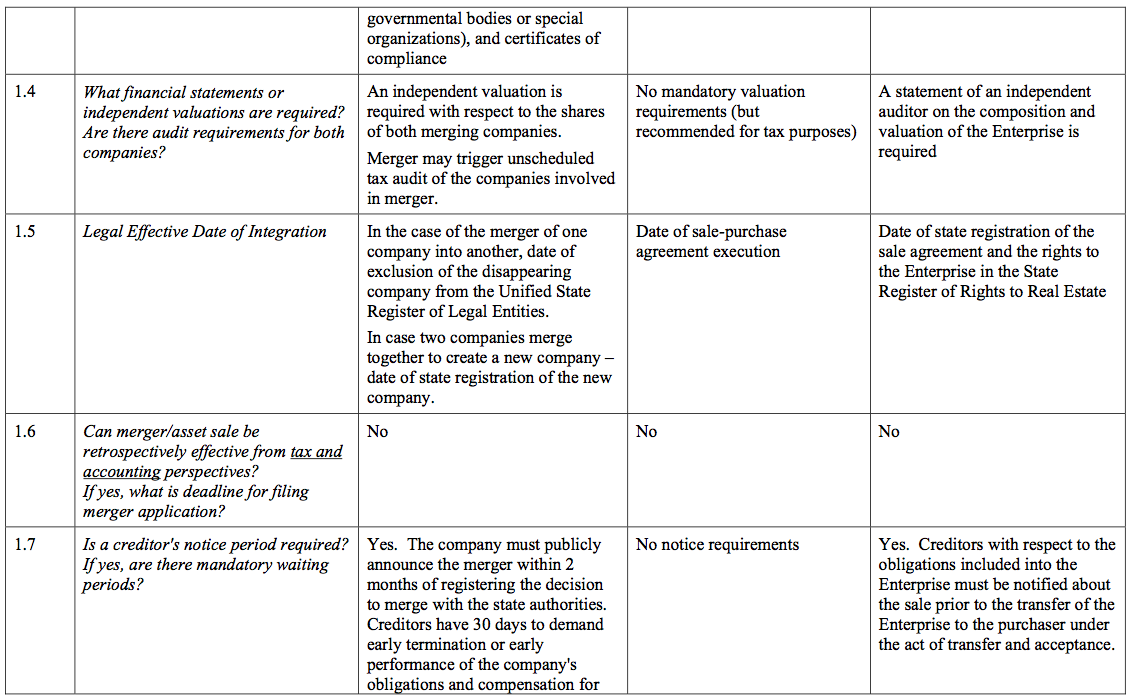

Russia

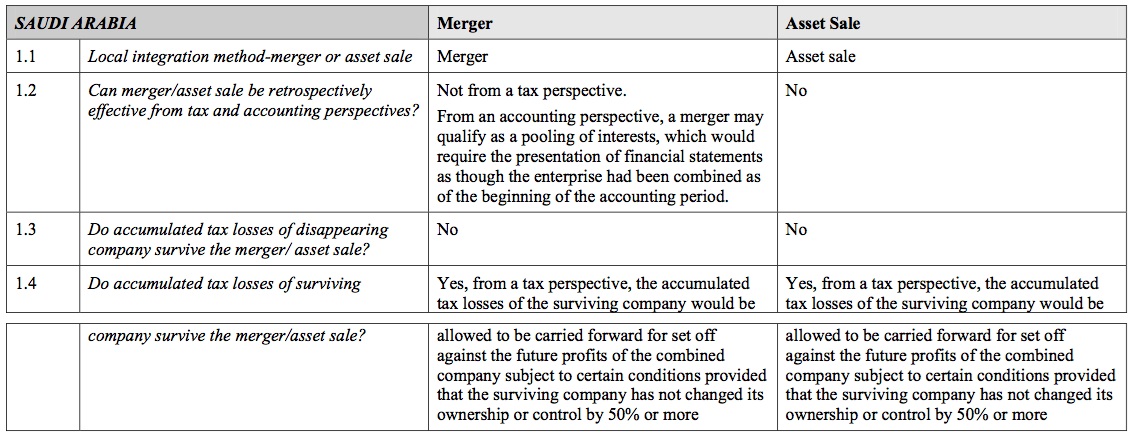

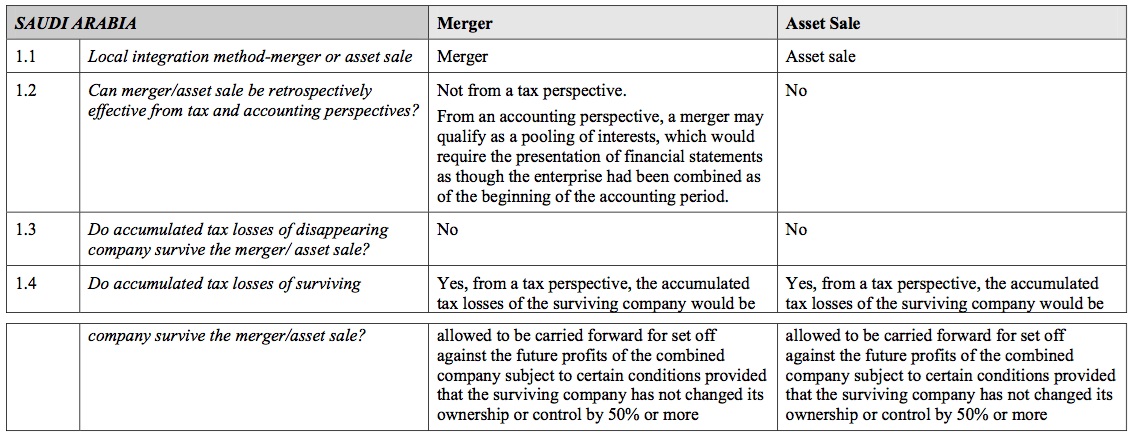

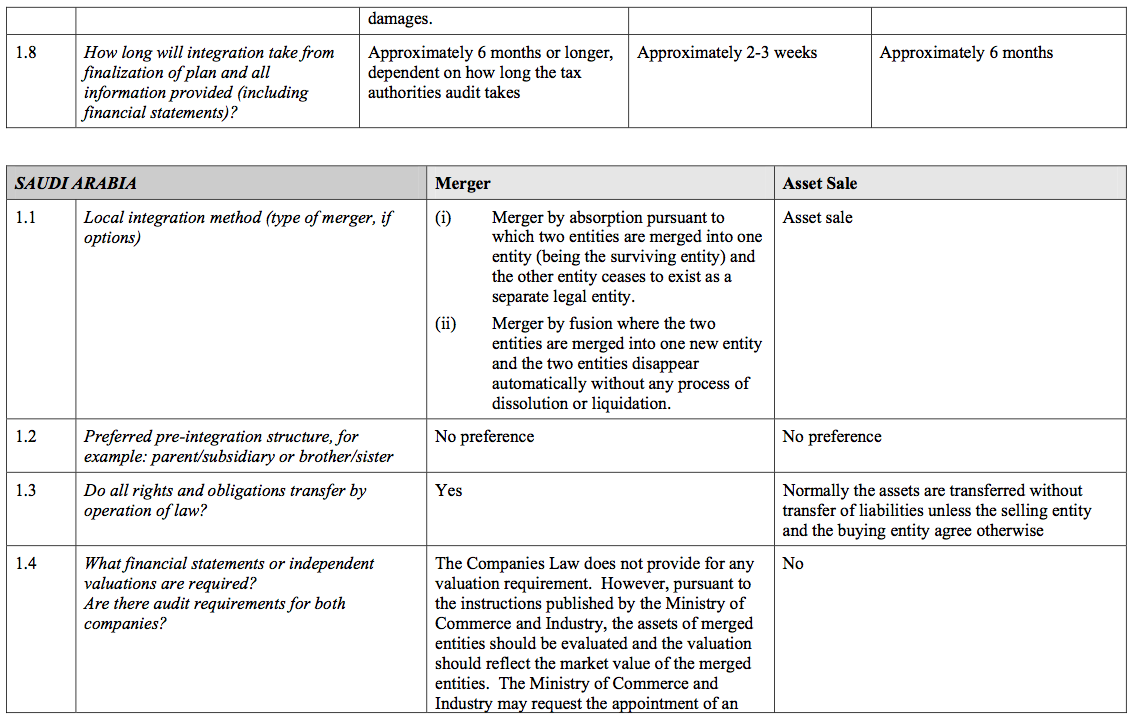

Saudi Arabia

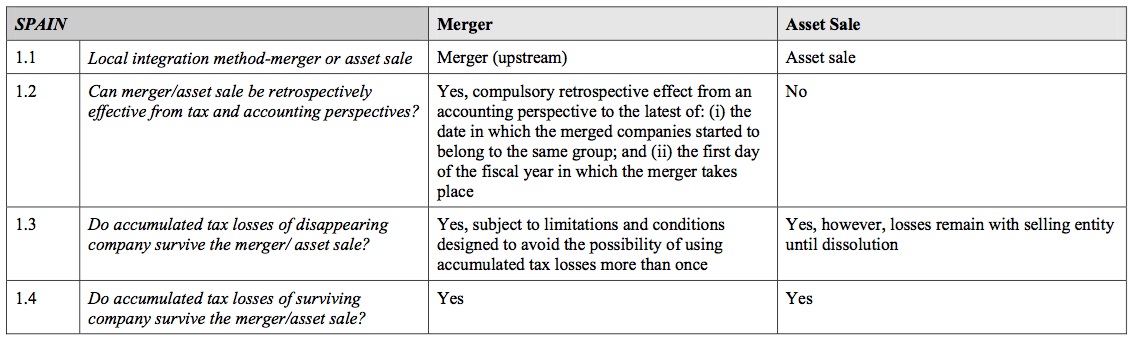

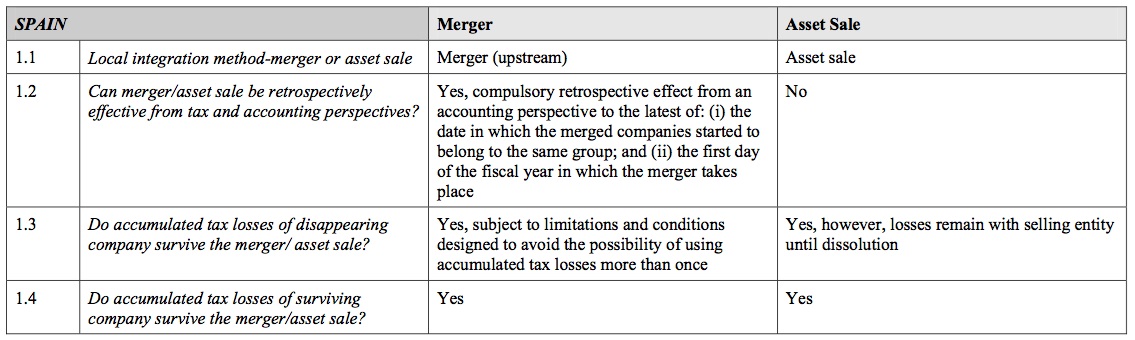

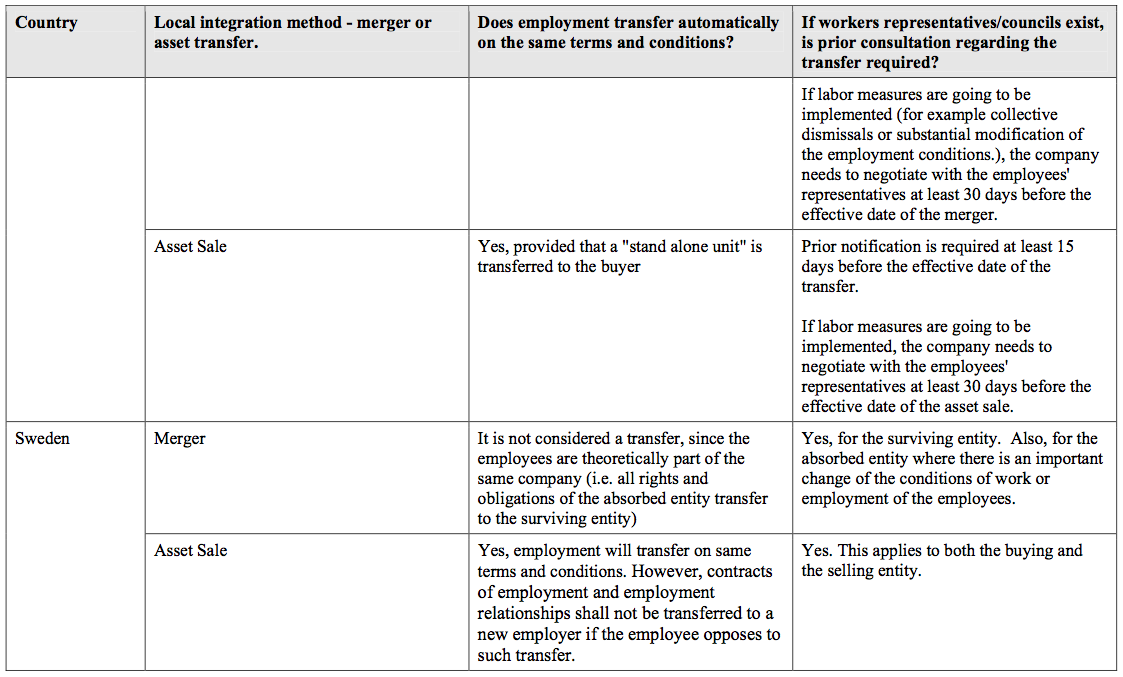

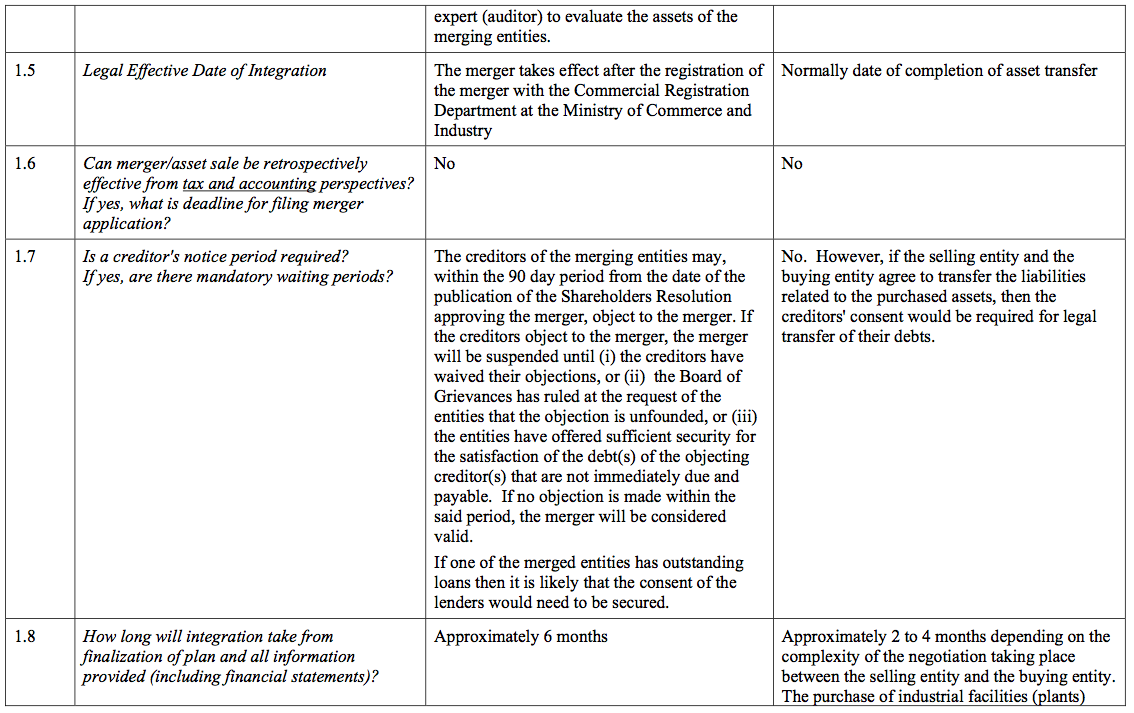

Spain

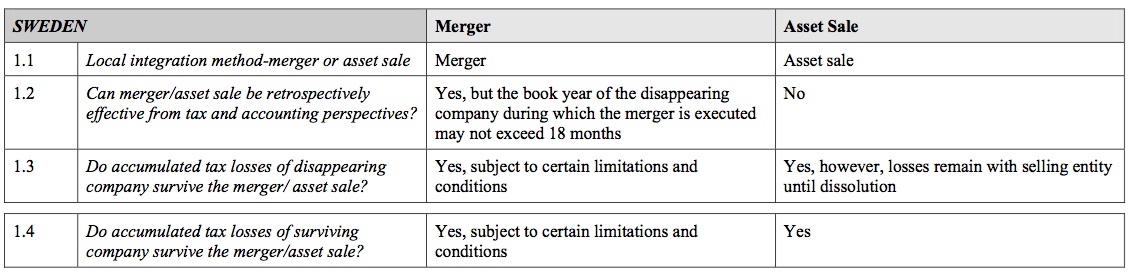

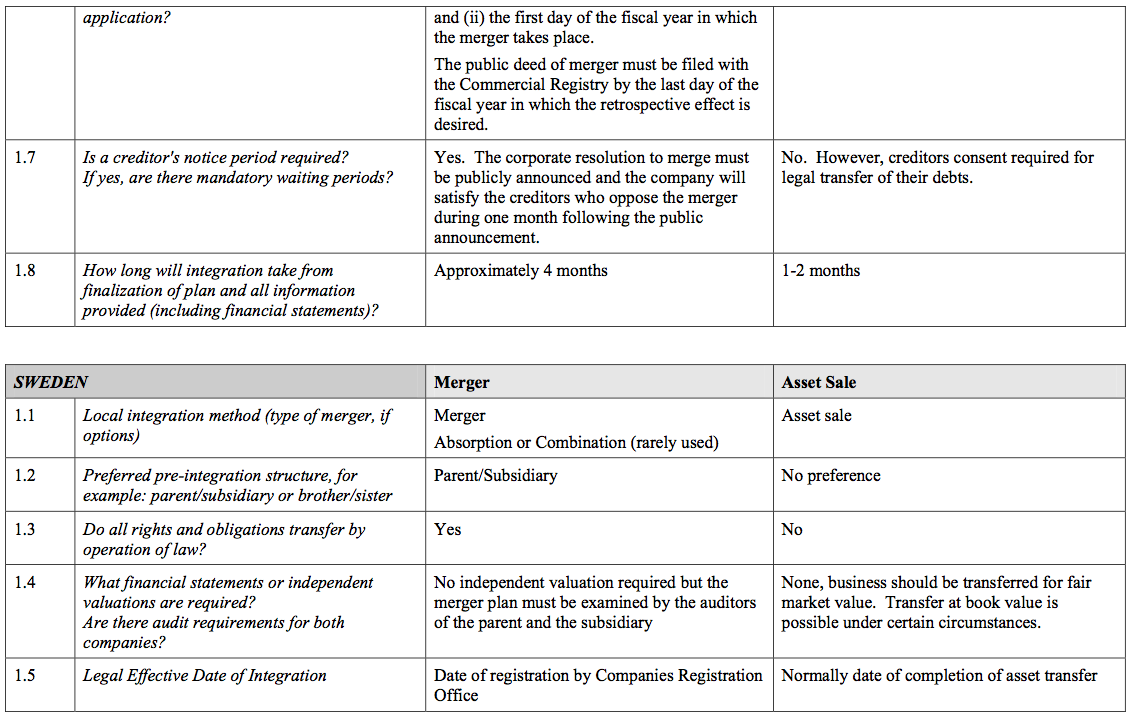

Sweden

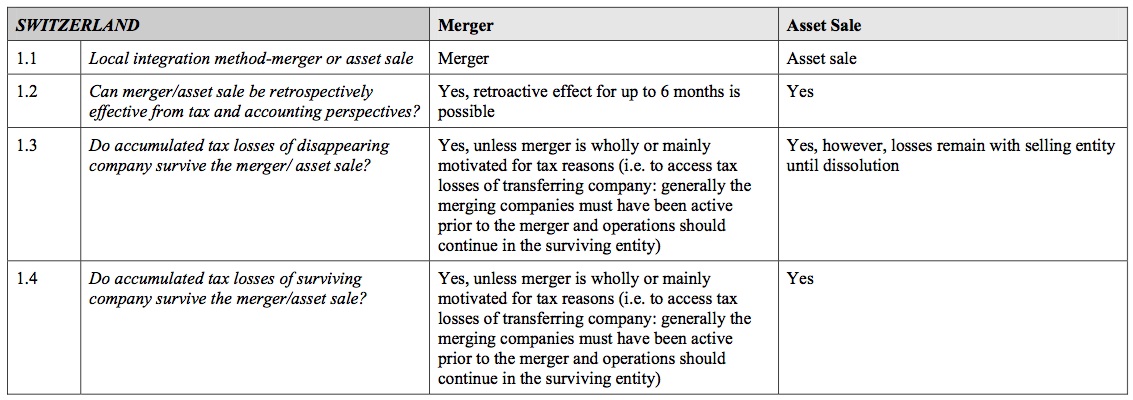

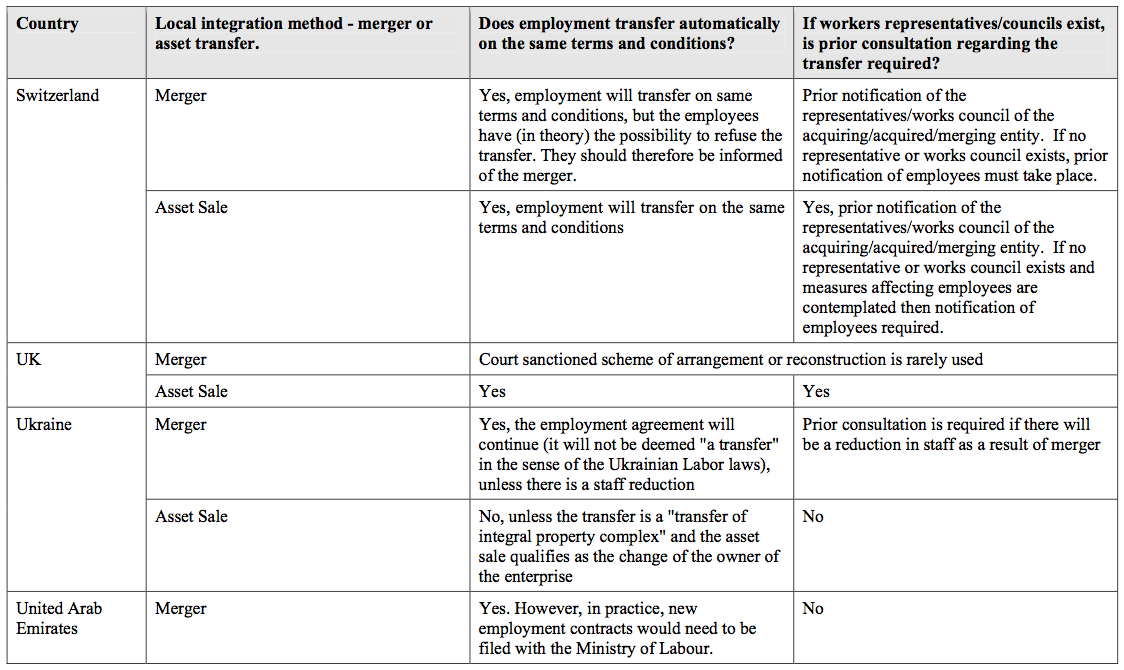

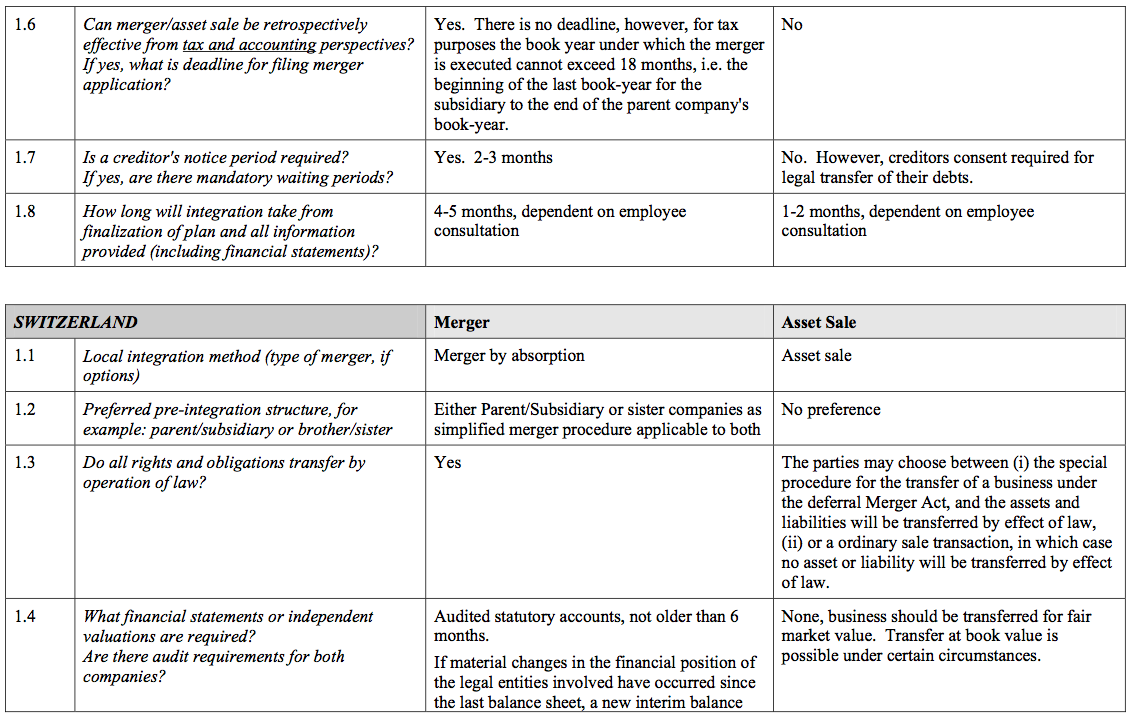

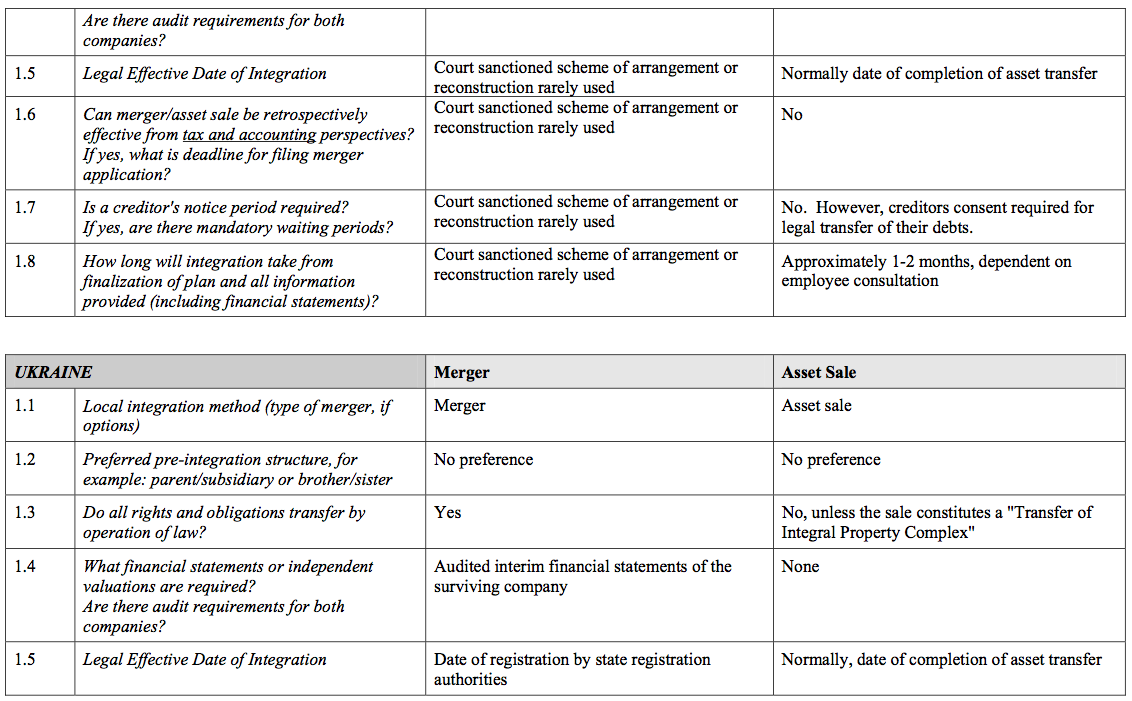

Switzerland

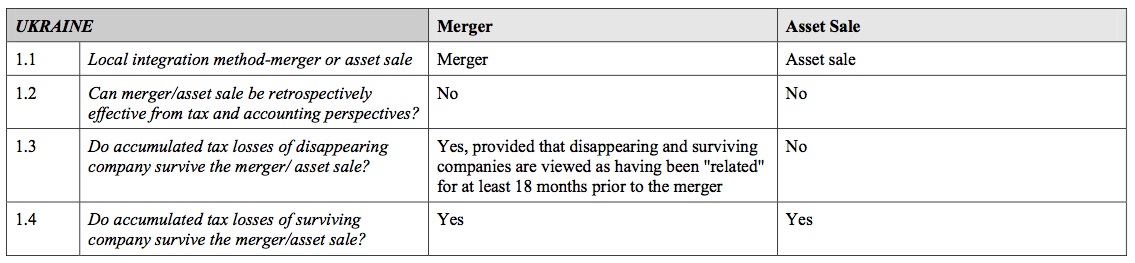

Ukraine

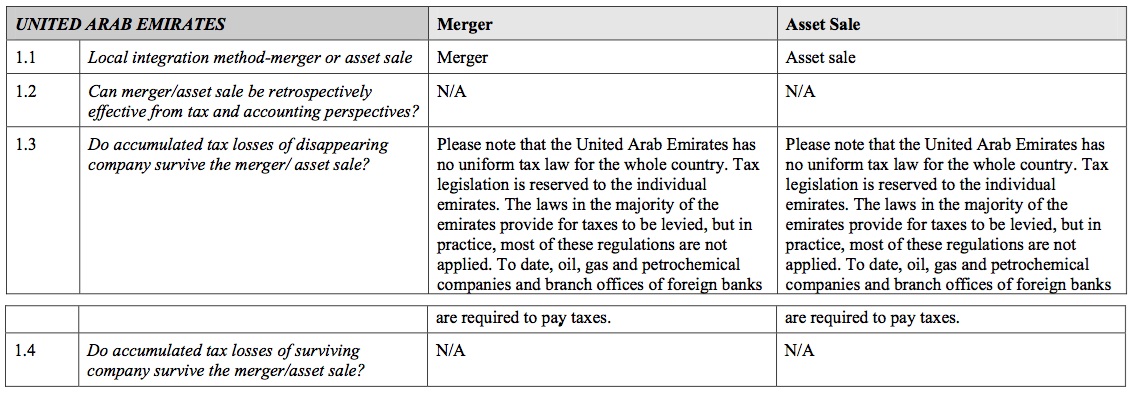

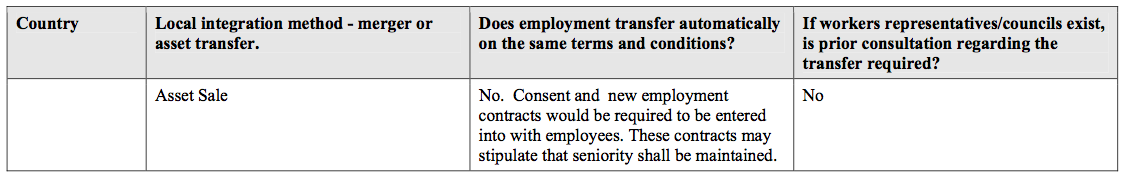

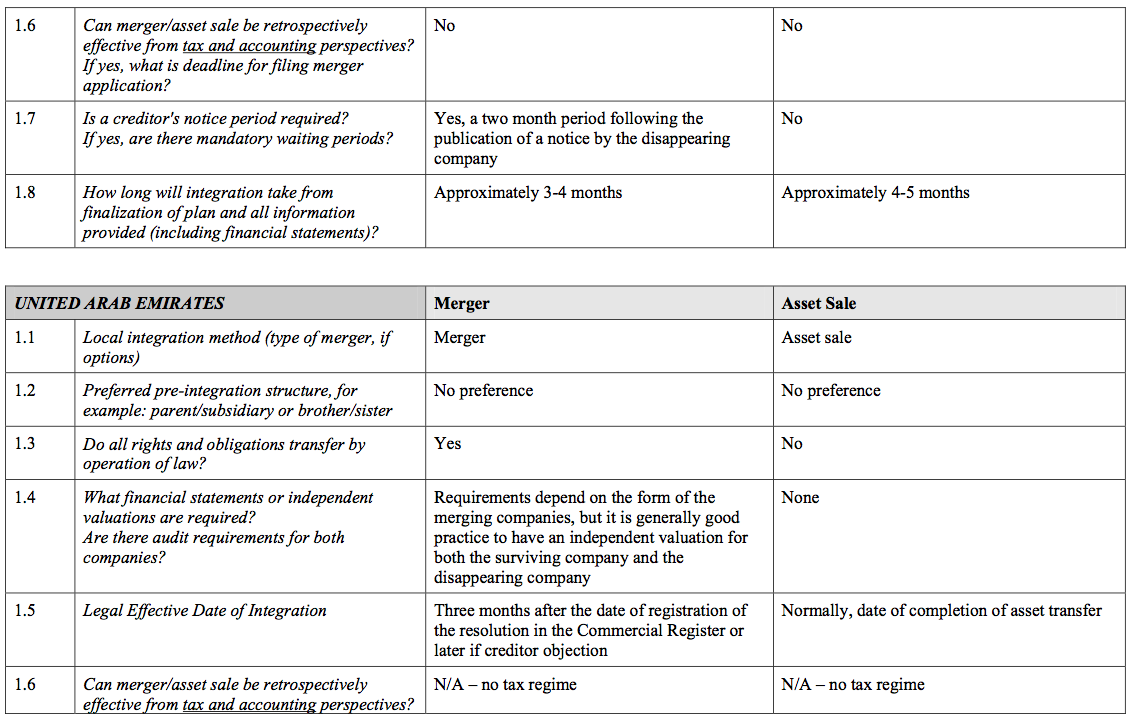

United Arab Emirates

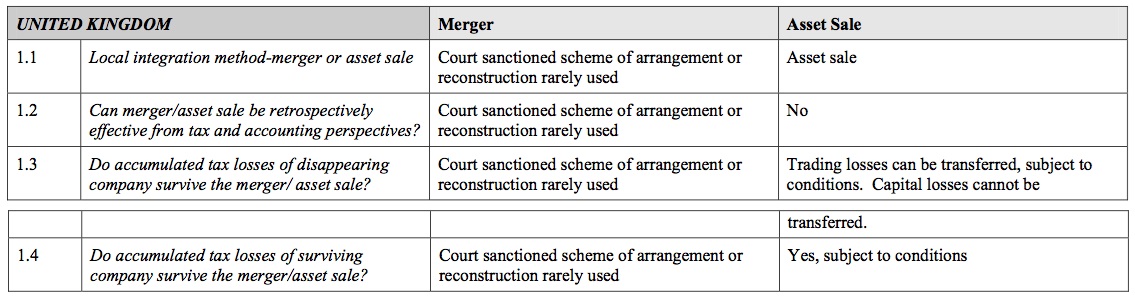

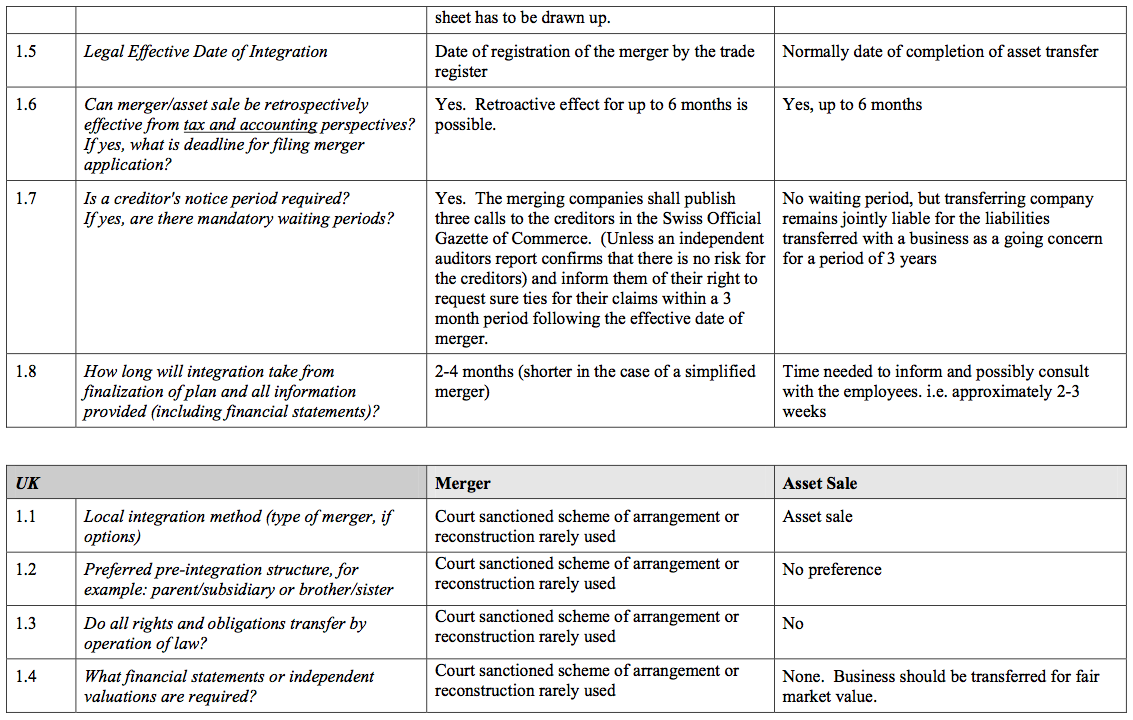

United Kingdom

SECTION 4: A COMPREHENSIVE INTEGRATION CHECKLIST

A. Data Collection Phase

1. Identification of Strategic and Key Objectives

1.1 What are the company’s business goals?

1.2 What are the company’s priorities?

1.3 What are the company’s plans for employee transfers and reductions in workforce?

1.4 What are the company’s timing and sequencing priorities?

1.5 Are there entities that should not be integrated, or should the integration method be driven by isolation of liabilities considerations (for example, environmental)?

1.6 What are the constraints to moving assets, entities and people?

2. Key Information Gathering

2.1 What countries do the businesses operate in?

2.2 Where are the revenues being earned?

2.3 Where are the taxes being paid?

2.4 Where are the tax attributes (for example, accumulated tax losses, tax credits, tax holidays)?

2.5 Where are the tangible assets?

2.6 Where are the intangible assets?

2.7 What are the company’s and the newly-acquired target’s current operating models and transfer pricing policies?

3. Local Due Diligence Review

3.1 Following the identification of the high level strategic objectives and characteristics of the group, the next stage is a more detailed information gathering phase.

3.2 Identify information obtained as part of the due diligence process conducted for the original acquisition of the target’s parent company.

3.3 Company information (see Exhibit A at the end of Section 4 for detailed checklist).

3.4 Branch and Representative/Liaison Offices information (see Exhibit B at the end of Section 4 for detailed checklist).

3.5 Details of any works council/union/employee representation, including regional forums such as European Works Councils, and any employee change in control/severance plans that may trigger benefits on an integration.

4. Technology

4.1 Audit and evaluate IT systems and the requirements of the participating entities, including impact on supply chain and financial reporting.

4.2 Carefully plan IT integration.

4.3 Prepare the groundwork to ensure that the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), invoicing and accounting IT systems are capable of and are properly configured to begin processing transactions for the newly integrated entities, for example:

- if the acquired subsidiaries are using a different order processing and invoicing software, ensure that after the integration the acquired company products can be properly invoiced under the pre-existing order processing and invoicing software.

4.4 Ensure that IT systems are configured to accommodate any changes in the order flow or other intercompany commercial arrangements that may be planned as part of the integration, for example:

- switching to a commissionaire structure from a buy-sell distributor arrangement.

5. Regulatory and Antitrust Issues

5.1 Does the integration require any merger control notification or approval?

5.2 If merger control approval was obtained prior to closing of acquisition, does it cover post-acquisition integration?

5.3 If information will be exchanged prior to closing and/or during a merger control suspension period, is the information to be exchanged:

- permitted information;

- controlled information; or

- prohibited information?

(See Section 8 for further details.)

5.4 Does integration require any foreign investment approvals or registrations? For example:

- registration of new shareholders.

5.5 Does integration require any exchange control notices or approvals?

5.6 Do local laws require the surviving entity to obtain:

- general;

- asset-specific; or

- industry-specific governmental permits, licenses or approvals to continue the merging/transferring entity’s business, for example:

- general laws and regulations governing general business licenses and permits, transfer of intellectual and real property, or industry-specific laws and regulations covering areas such as defense, media, food and drug, health, safety, pharmaceutical, utilities, brokering, banking, securities.

5.7 Has the merging/transferring entity received any governmental subsidies, grants or other incentives?

- if so, does the integration require notice to or approval by the relevant government agency?

6.1 Review, integrate and update corporate compliance programs for example:

- Sarbanes-Oxley (including auditor independence, certification and reporting, directors’ loans, ethics, whistle blower protection and document retention issues);

- Foreign Corrupt Practices Act;

- boycott;

- export controls;

- bribery/corruption;

- money laundering;

- antitrust/competition;

- corporate governance.

B. Strategic Integration Mapping

7. Integration Method

The information gathering phase will allow planning to commence on the local integration methods.

7.1 Identify local integration method:

- does local law provide for a statutory merger; or

- will the integration have to be accomplished by means of a business/asset transfer with subsequent dissolution?

7.2 Identify surviving entity after careful consideration of all relevant factors, for example:

- preservation of tax attributes;

- liabilities of participating entities;

- impact on employees and employee representative bodies;

- internal operational and “political” considerations.

7.3 What is the preferred pre-integration structure? Should the entities to be integrated be structured as:

- brother/sister; or

- parent/subsidiary prior to the integration?

7.4 What documentation is required to effect the proposed integration? for example:

- notarial deeds;

- asset sale agreements;

- registrations with the commercial registry or trade register, amendments of share registers.

7.5 Will the chosen integration method require the establishment of new entities?

- if yes, consider the impact on timing, as in some jurisdictions, the establishment of a new entity may take several months and may also require new VAT registrations.

7.6 Will the chosen integration method require the registration of new branches, as in the case of a merger, branches of the merging entity may not automatically transfer to the surviving entity?