Publications M&A Deal Evaluation: Challenging Metrics Myths

- Publications

M&A Deal Evaluation: Challenging Metrics Myths

SHARE:

By Bob Haas, Angus Hodgson – A.T. Kearney

In the world of mergers and acquisitions, emphasis is often placed on evaluation metrics that look as if they tell the story, but they can be misleading.

The presentation was over. The CEO of a global business-services group had been part of a due diligence process to advise on whether or not to proceed with a major European acquisition. Our job was to help the CEO and the board answer some important questions: Was the target company a good fit? How did synergies stack up against the risks? Did the target company’s sector show potential for growth?

Our findings were less than encouraging. They suggested limited growth going forward, and even though the potential for synergies was good, the risks were significant, and there were doubts about the company’s ability to deliver those synergies.

As we walked out of the meeting, the CEO was digesting all that he had just heard and contemplating the board’s likely reaction to our findings. Then he spoke: “Well, there’s one thing we can say about this acquisition — it’s highly earnings accretive.”

An argument to support the myth that EPS accretion equates to value creation is that “some people believe it does” — a misperception that is then priced into the stock.

What does that mean? Does the fact that a deal is accretive necessarily mean that it’s a good move? Conversely, are deals that dilute earnings per share (EPS) necessarily bad moves? Should we even use EPS as a measure by which to evaluate an M&A transaction?

In this paper, we discuss findings from our research into the metrics and analyses most frequently used to evaluate proposed mergers and acquisitions. The research introduced a surprising insight: The impact on EPS is by far the most emphasized metric used to evaluate proposed M&A transactions between public companies.

With this in mind, we look at two common and related myths surrounding EPS and demonstrate why these are at best unhelpful and at worst potentially misleading. We also examine what business leaders and market analysts should focus on instead. As always, our advice is pragmatic: Stick to the business fundamentals.

How Do They Get It So Wrong?

It is widely recognized that a significant percentage of M&A transactions fail to deliver value to shareholders. What goes wrong? How is it that acquisitions on average seem to create negligible returns? It can be tempting to blame poor merger integration for the meager returns, and certainly the execution of an integration can have a major impact on whether or not a transaction is regarded as successful. However, it may also be useful to consider if the deal was worth doing in the first place. Maybe some transactions should never have happened.

With this in mind, A.T. Kearney joined forces with the UK’s Investor Relations Society (IR Society) to understand exactly which metrics and analyses get the most emphasis in evaluating proposed M&A transactions. Maybe the solution to the question of “what goes wrong” lies in the tools used to filter (and one would hope eliminate) value-destroying transactions from those that create value.

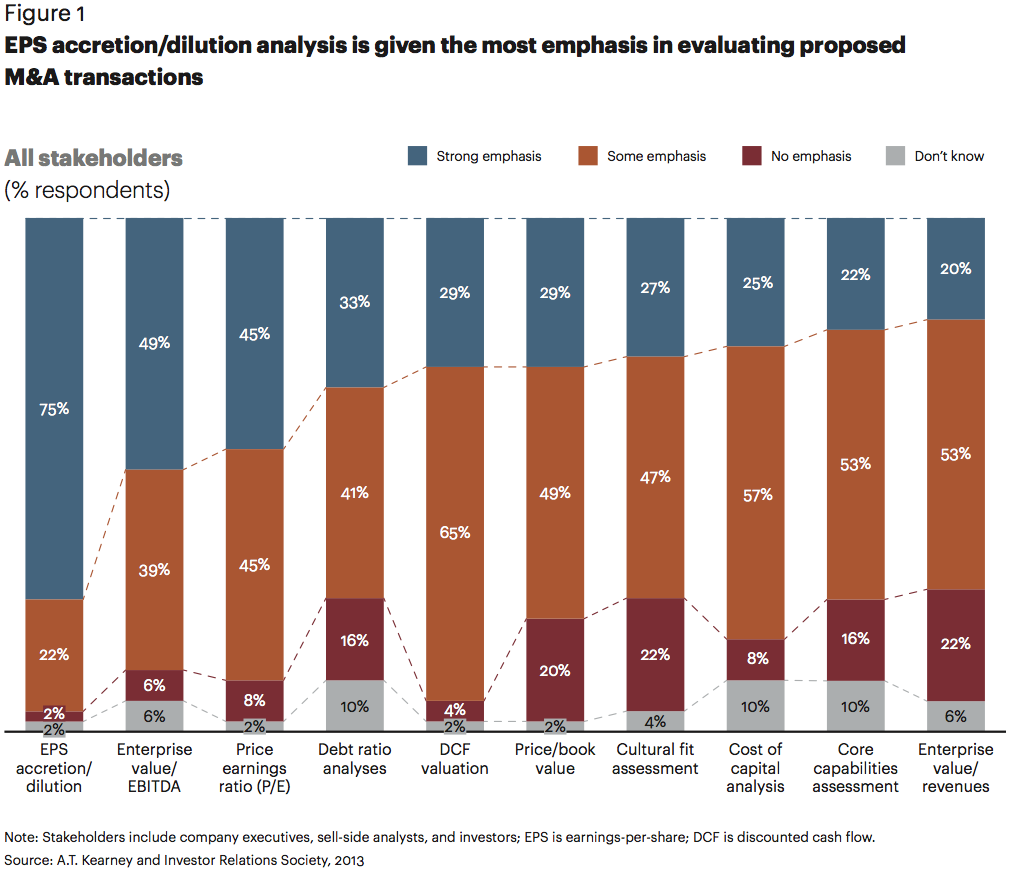

Investor Relations professionals were surveyed to gauge the views of key stakeholders — company executives, sell-side analysts, and investors—on 10 frequently used metrics and analyses (see “M&A Metrics — Why the Difference in Emphasis?”). We found that EPS analysis is used most, and by a wide margin: 75 percent of respondents ranked it in the “strong emphasis” category, fully 26 points ahead of enterprise value/EBITDA, the number two rated metric (see figure 1).

M&A Metrics: Why the Difference in Emphasis?

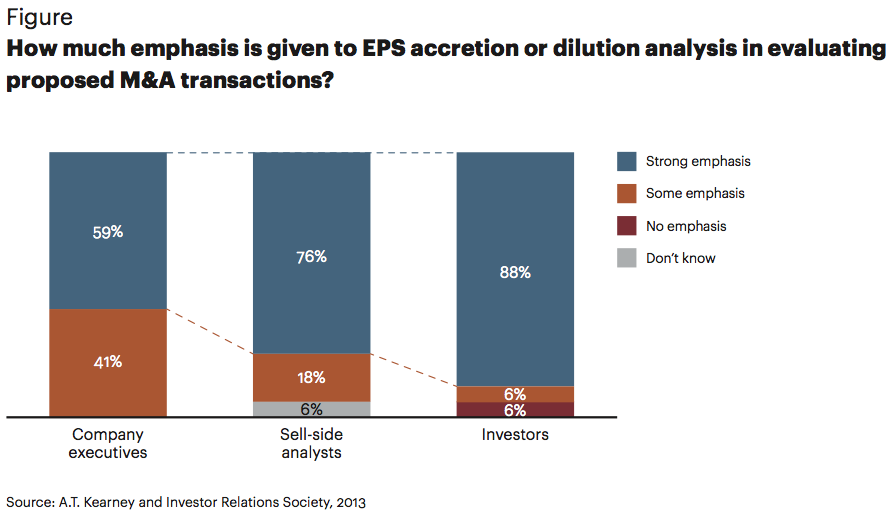

To learn how different stakeholder groups view earnings-per-share (EPS) analysis as a metric for evaluating mergers and acquisitions, members of the UK-based Investor Relations Society were surveyed regarding the emphasis that key stakeholders (company executives, sell-side analysts, and investors) give to 10 frequently used metrics and analyses. All stakeholders have “skin in the game” but, as it turns out, significantly different perspectives on the extent to which they emphasize EPS analysis. The biggest contrast was among those who strongly emphasize EPS — company executives (59 percent) and investors (88 percent). Sell-side analysts were in the middle at 76 percent (see figure).

Perhaps these results are not so surprising. Company executives are likely to take a more all-encompassing, or perhaps more strategic, view of a merger’s impact. But should that be the case? Shouldn’t all parties be striving for the same objective assessment of a deal’s benefits and the extent to which it will strengthen competitive position and ultimately, generate shareholder value through increased cash flow?

This raises an interesting question: Which group is more correct? Our answer is that while company executives place significantly less emphasis on EPS analysis, all three groups pay far more attention to the metric than it merits.

What Exactly Is EPS Accretion and EPS Dilution?

Before we go any further, let’s define what we mean by EPS accretion and EPS dilution. A company’s EPS — again, earnings per share — is simply the total profit allocated to each outstanding share.

EPS growth can be achieved either organically or inorganically through M&A activity, and few would argue that organic EPS growth is anything other than a positive indicator. EPS growth delivered through M&A activity, that is, EPS accretion, is fundamentally different. Yet there are some commonly held beliefs — or, more accurately, myths — to suggest this distinction is not fully understood by many experienced investment professionals, including some company executives (see “The Lingering Myth of EPS Accretion”).

Two myths are widely believed:

- EPS accretive transactions create value.

- EPS dilutive transactions destroy value.

As we will see, neither of these preconceptions stands up to scrutiny. Why then do so many executives and others persist in using EPS analysis to evaluate M&A transactions?

The answer comes down to views about valuation. A company’s stock is frequently valued on the basis of its EPS by applying a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio. Based on the assumption that an acquiring company’s P/E ratio will stay the same after an acquisition, if earnings per share increase, then the company’s overall value will increase, ostensibly as a result of the deal.

The Lingering Myth of EPS Accretion

In an examination of 30 acquisitions performed and announced by publicly owned companies, 68 percent referred to the merger’s potential impact on EPS. The prominence given to this metric at the announcement reinforces the lingering belief that EPS is a proxy for value creation.

The EPS accretion myth has lingered for a long time. Here’s why. At first glance, EPS accretion appears to be a simple, and therefore appealing, way to determine or communicate whether or not a transaction will create value. In fact, it is logically and mathematically flawed.

Large mergers and acquisitions almost always involve the high drama of risk and reward for the parties involved. M&A can make—or break—a n executive’s reputation or career, and multimillion-dollar fees and bonuses can be won or lost. Given all that, no wonder every possible argument supporting M&A deals is applied by those trying to make them happen.

This is precisely why analysts and other stakeholders need accurate evaluation tools: to make sure all the arguments for making the deal hold water. Despite the frequency with which EPS accretion is alluded to or used to bolster arguments for the deal, the metric doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

What’s the Catch?

But, there’s a catch. To understand it you need to consider the fundamentals of why one company has a higher P/E ratio than another in the first place. It is because the market believes the earnings of the company with the higher P/E ratio — call it Company A — will rise faster than those of the company with a lower P/E ratio (Company B). Now suppose Company A buys Company B, using its stock as the acquisition currency. As a result of the purchase the EPS of the combined company will be higher than that of Company A had it not made the acquisition — thus the transaction is EPS accretive for Company A.

They call it the “bootstrap game.” If companies can fool investors by buying a company with lower P/E rated stocks, then why not continue to do so?

But being EPS accretive comes with a downside — and that’s the catch. The newly combined company will also have a lower earnings growth rate than Company A would have had as a standalone company. So while the EPS of the post-acquisition company will be higher than that of the pre-acquisition Company A, its P/E ratio will be lower due to its acquisition of the lower-P/E rated Company B.

In fact, the reduction in the P/E ratio, all other things being equal, will exactly counterbalance the impact of the higher EPS. The result is that the valuation of the newly combined company will reflect the blended higher EPS and lower P/E ratio of the two original companies. In other words, no value is created.

A key reason for doing an M&A deal is, of course, the synergies that can result. By increasing the new entity’s combined earnings, synergies can add enough value to make the combined company worth more than the two individual companies were before the merger. It is important to note that the increased value results from the synergies created, not from the deal being EPS accretive or dilutive. It is quite possible that highly dilutive deals offer the greatest opportunities for delivering synergies.

An argument sometimes put forward to support the myth that EPS accretion equates to value creation is that “people believe it does.” This becomes reality as the misperception is priced into the stock.

Richard A. Brealey and Stewart C. Myers write about this idea in their seminal textbook, Principles of Corporate Finance. They call it the “bootstrap game.” If companies can fool investors by buying a company with lower P/E rated stocks, then why not continue to do so? The flaw in the bootstrap game is the need to keep the market fooled, hoping it doesn’t notice that the acquiring company’s earnings growth potential is becoming progressively more diluted.

The inevitable result of pursuing such a strategy to its logical conclusion by continuing to acquire lower P/E rated companies is clear: In the same way a Ponzi scheme must eventually fail due to the lack of underlying value creation, the P/E multiple of the acquiring company must fall as it becomes increasingly evident to the market that no value is created.

What’s the Alternative for Evaluating Proposed Mergers?

Our advice for evaluating a proposed merger is characteristically pragmatic: Stick to the fundamentals. M&A can deliver significant competitive advantage and value to shareholders, but the criteria by which to assess just how much must answer fundamental business questions:

- Is the proposed merger strategically logical?

- Will it deliver cost, revenue, or other financial synergies?

- Will it build management or other capabilities?

- Is the combined company capable of delivering the synergies?

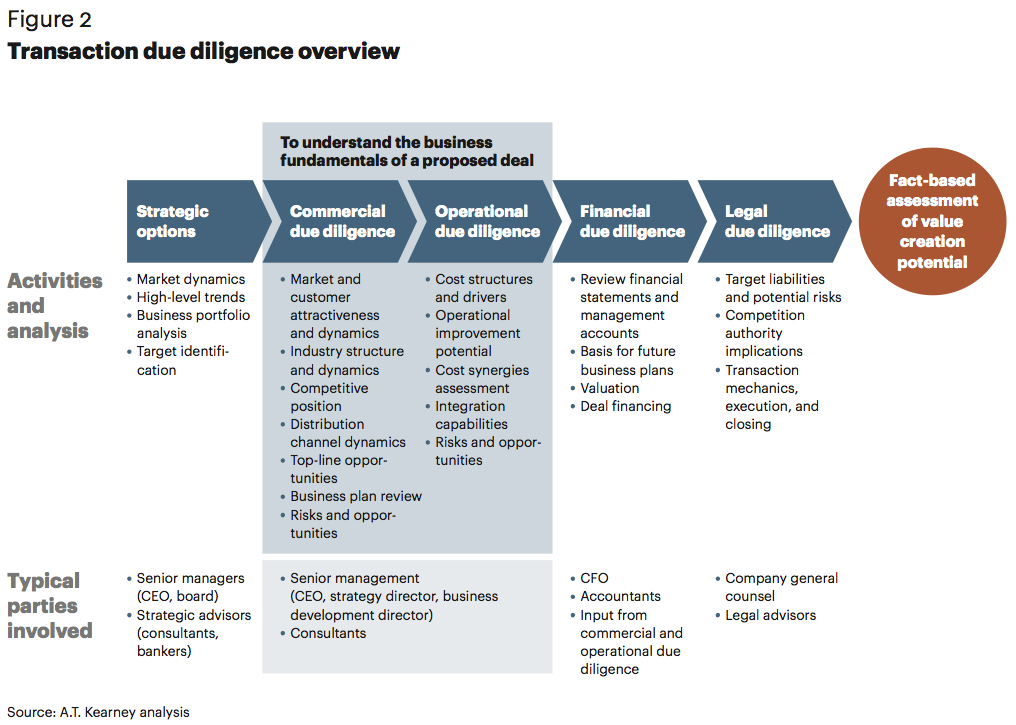

A thorough, fact-based due diligence is the best way to answer these questions (see figure 2).

Accretion or dilution is a fact of doing deals, but is not a measure of potential value creation. For that, you need to examine the deal’s business fundamentals.

Of course, there is also a role for using many of the M&A metrics and analyses described in figure 1 as part of an overall assessment. These can play a complementary role in developing a full perspective on a transaction. Used in isolation, however, and without a clear understanding of their limitations, they have a tendency to give a very limited view of the real potential for value creation.

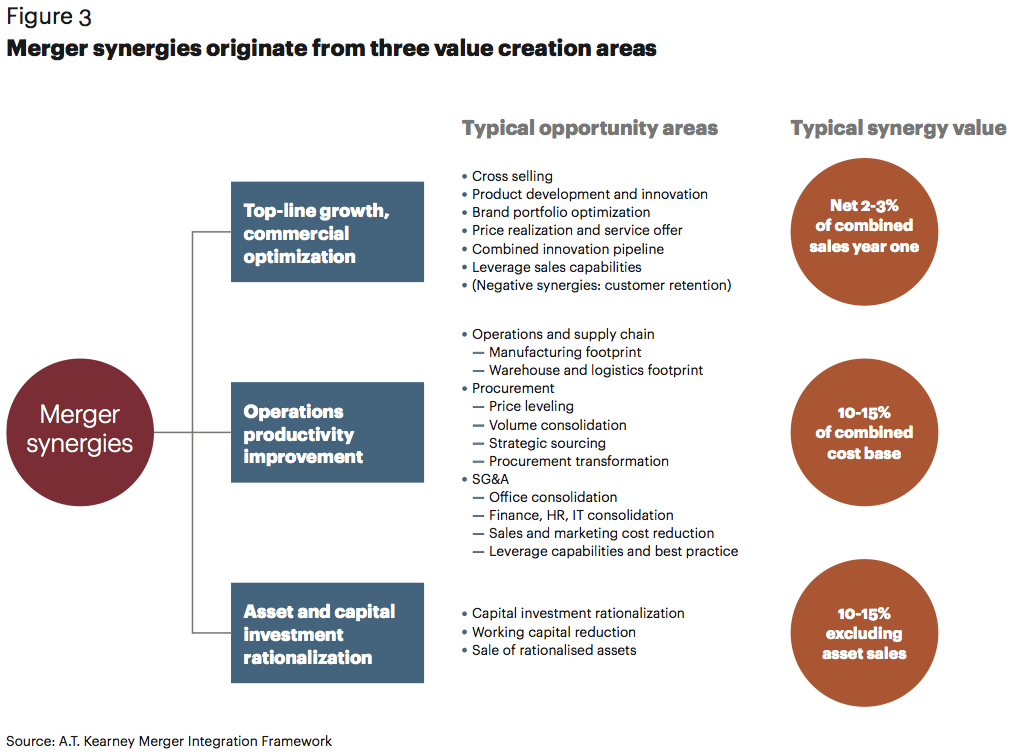

Ultimately, any value an M&A transaction creates must translate into future cash flow, resulting from synergies in three value-creation areas: topline growth, operations productivity, and asset and capital investment rationalizations (see figure 3).

And then there’s the crucial question of how much to pay for a deal and who will realize the value it creates. If the net present value (NPV) of future synergies is paid to the selling shareholders in an acquisition price premium, even the most synergistic of mergers can result in value destruction for the acquirer’s shareholders. Always consider who will be the winners in an M&A transaction—the final outcome is rarely the same for all parties.

EPS Myths Revisited

The moral of the story is this: Too often, too much emphasis is placed on whether a deal is EPS accretive or dilutive. These are time-honored metrics that appear sensible but in reality do not answer the most important question: Should we do the deal? Let’s review the two commonly held myths and why they don’t work as M&A evaluation measures.

EPS-accretive transactions create value. Not necessarily. Accretion is a relative measure that simply shows the company being acquired has a lower P/E rated stock.

EPS-dilutive transactions are value destroying. Again, not necessarily. In fact, EPS-dilutive transactions can increase value when the target company has good growth potential and the strategic logic for the deal is strong.

The fact is that EPS analysis is not a useful tool for evaluating the merits of proposed M&A transactions. Accretion or dilution is a fact of doing deals but is not a measure of potential value creation. For that, you need to examine the deal’s business fundamentals.

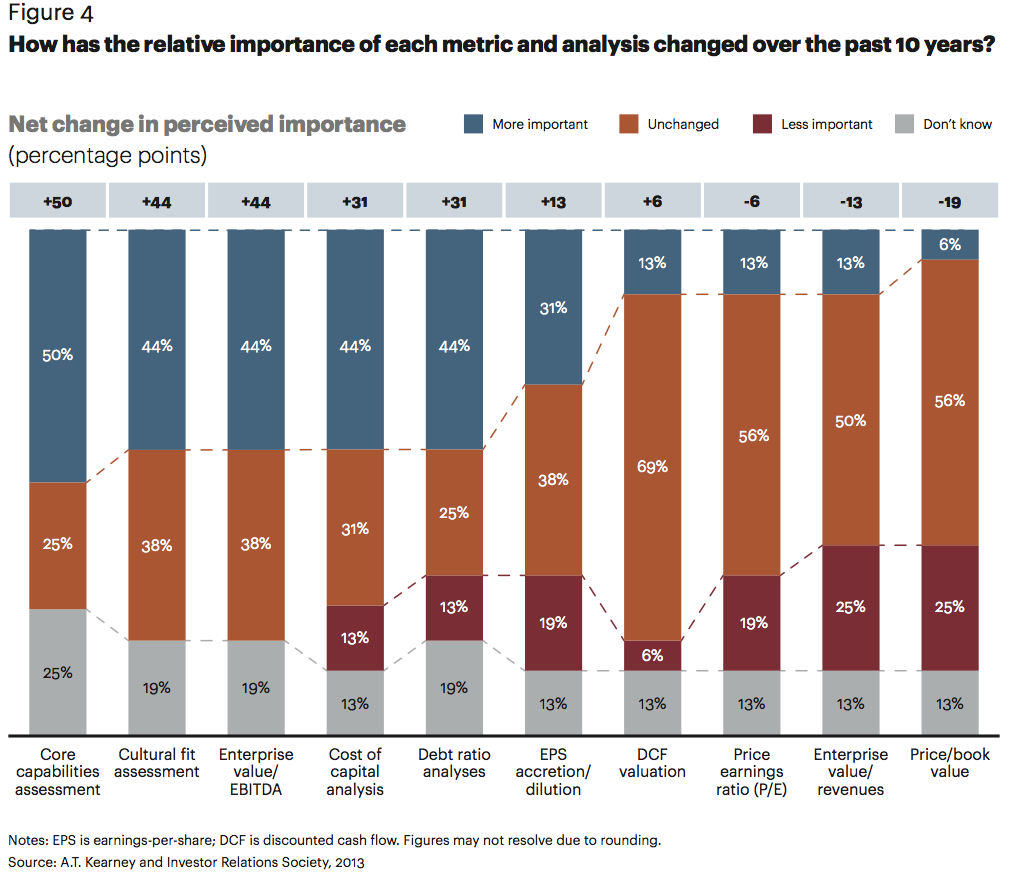

Our research reveals one more insight: how the emphasis given to the different metrics and analyses has changed over the past decade. Two measures, core capabilities and cultural fit, the most qualitative among the 10 examined, are among the top measures that have “become more important” in the past decade (see figure 4). This suggests stakeholders are becoming increasingly aware of the conditions necessary for merged organizations to deliver sustained value after the deal has closed and the merger integration process begins.

Quick and Easy Shortcuts Can Be Misleading

This is not to say a proposed transaction’s impact on EPS isn’t important. It is something that needs to be understood and communicated to investors. The fact remains, however, that doing an EPS-accretive deal is easy—simply buy a company with a lower P/E-rated stock than your own. So the next time someone says or implies that an M&A deal is a good one because it is EPS accretive, ask why the market gave the target company’s stock a lower rating in the first place. To truly understand whether a proposed acquisition will create value requires evaluating the strategic rationale for making the deal, and if it will deliver enough synergies to create value. As with many things in life, quick and easy answers can be misleading.

(The authors wish to thank their colleagues Oliver Lawson and Olga Wittig and the Investor Relations Society for their support.)

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter