Publications Driving Banks’ Value Through M&A

- Publications

Driving Banks’ Value Through M&A

SHARE:

Strategic Mergers And Acquisitions Are Reshaping European Banking

M&A activity in the financial services industry has increased significantly over the last few years. The crisis in the financial markets is now providing additional momentum for M&A activity, with a number of very sizeable institutions suddenly up for sale. Whether their goal is to simply acquire a competitor at a low price, to enter new growth markets, to consolidate mature markets at the national or European level or to restructure the value chain, more and more banks are considering M&A as a normal strategic instrument. But with some studies putting the failure rate of mergers and acquisitions as high as 50%, how can banks manage post-merger integration successfully to realize true growth in value?

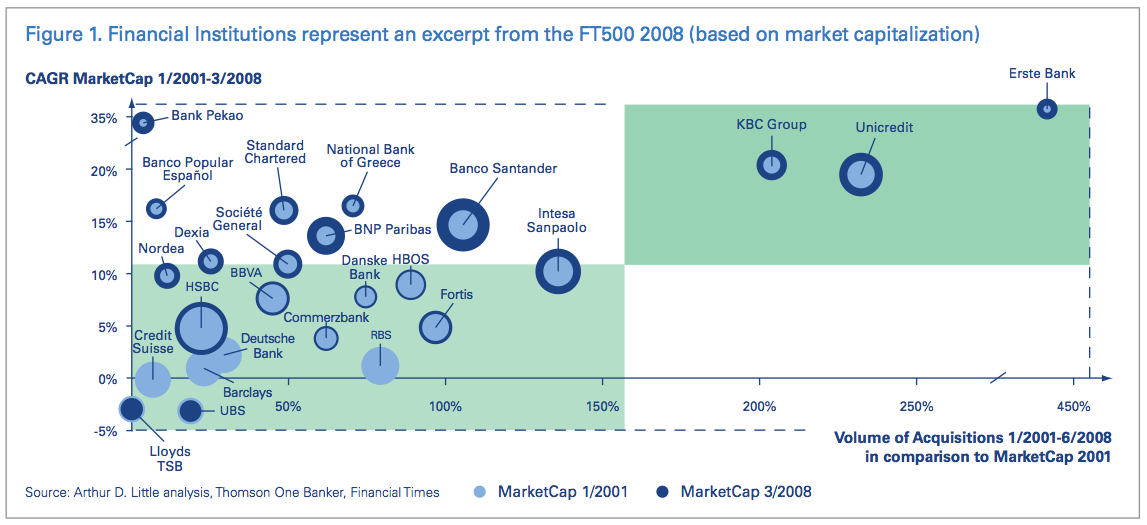

In recent years, mega-deals have helped to reshape the banking landscape, catapulting some banks to the very top of the global league table in terms of market capitalization. UniCredit is a perfect example. In the 2001 FT 500, the bank ranked 29th among European financial services firms in terms of market capitalization. Two landmark acquisitions (HVB/Bank Austria and Capitalia), together with several medium-sized and smaller acquisitions as well as a strong presence in Eastern Europe, propelled UniCredit to #4 in 2007. At the opposite end of the spectrum, banks such as Deutsche Bank, UBS, Credit Suisse and Lloyds TSB, which have been less active in M&A, stagnated or even shrank in terms of market value.

Arthur D. Little’s analysis of European banks in the FT500 index shows a strong correlation between M&A activity and growth in market capitalization (see figure 1).

A closer look at the nature of the deals in the banking sector reveals three main drivers: geographic expansion into growth markets in Central and Eastern Europe, consolidation in mature markets, and restructuring of the value chain.

Geographic expansion: going East

As a result of the banking industry privatization in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the region has been a boom market over the last ten years. A number of Western European banks have seized this unique opportunity and built a presence in several countries in the region via acquisition.

UniCredit now has the strongest position in CEE. Through its acquisition of HypoVereinsbank, the bank added the sizable portfolio of Bank Austria subsidiaries in the East to its own Eastern Europe portfolio.

Similarly, several less prominent banks with small home markets have managed to build a respectable presence in CEE, including Raiffeisen International and Erste Bank from Austria as well as KBC from Belgium. Erste Bank, for example, has developed from a small national institution with a market capitalization of only €2.3 billion at the beginning of 2001 into one of the biggest players in the Eastern European market, increasing its market capitalization to a peak of €20 billion in 2008 (before the collapse of the financial markets).

Consolidating mature markets

Consolidation has been a recurring theme in some European countries, e. g. with UniCredit/Capitalia and Intesa/San Paolo in Italy or Crédit Agricole/Crédit Lyonnais in France. In Germany, where the market is fragmented due to the traditional three-tier banking system, consolidation mergers have been expected for many years. But even taking into account the acquisition of Dresdner Bank by rival Commerzbank, the need for further consolidation (e.g. Postbank, Landesbanken) is undisputed. Further consolidation has taken place cross-border, including: Santander/Abbey National, UniCredit/HVB, BNP Paribas/BNL, Crédit Mutuel/Citibank Germany, and the acquisition of ABN Amro by a consortium of Royal Bank of Scotland, Santander and Fortis.

In consolidation mergers, cost synergies are typically the main driver but revenue synergies are usually required on top to justify the price paid for acquisitions. Integrating large parts of the organizations, aligning processes, streamlining distribution networks and product portfolios, and, above all, migrating to one common IT platform are among the many challenges faced by the merging banks.

Restructuring the value chain

In recent years, many financial institutions have (re-)focused on their core competences. As a result, those parts of the value chain that are no longer considered a core competence are being spun off and eventually sold. This has been the case with the transaction units of many banks. In Germany, several Landesbanken, DZ Bank and WGZ Bank, as well as the savings banks have spun off their transaction banking units which, after a series of mergers, have become dwpbank – now serving savings banks, the cooperative banks and several others. Another series of mergers has brought about Equens in the Netherlands, serving banks including Citigroup, ING Bank, DZ Bank and Fortis.

Similarly, many banks have decided to focus on distributing asset management products through their established channels to their proprietary customer base and to leave the “production” to specialist asset managers. Again, scale benefits drive the consolidation. Specialist subsidiaries of Crédit Agricole/Banca Intesa and UBS/Hana Bank (South Korea), for example, have merged to take full advantage of joint operations. A comparable consideration also played a role in the takeover of ABN Amro.

Getting down to business

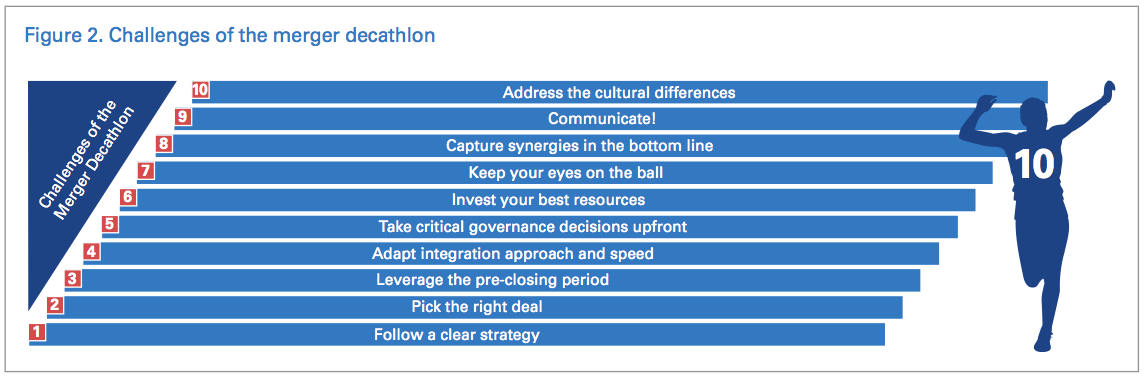

Whatever the strategic goal driving an acquisition, a successful deal by no means guarantees a successful integration. Various studies put the failure rate of mergers and acquisitions at 50% or even higher. Soft factors, such as cultural differences or lack of communication, are frequently quoted among the primary reasons for failure. While these factors do have a significant impact, much more is required to turn a merger into a real success story. To master the challenges of the “merger decathlon” (see figure 2), organizations and individuals have to excel in a broad range of disciplines.

That any merger should follow a clear strategy may sound trivial. But to many merging companies, synergy targets are much easier to define than a compelling strategic logic. This may be one of the reasons why the German Landesbanken find it so difficult to agree on a common consolidation path.

Picking the right deal involves two distinct steps: identifying the best target and performing a thorough due diligence. This includes assessing strategic and cultural fit, verifying intrinsic value and the potential for value creation, and fully understanding the risks involved. The risk dimension is often particularly challenging for banks ranging from credit and valuation risks to IT-related risks as well as the risk of losing large clients or key employees with critical know-how.

It is increasingly common for acquirers to leverage the pre-closing period to develop the high-level organization and governance structure, prepare the integration program and validate synergy assumptions.

Because no two mergers are exactly alike, it is necessary to adapt the integration approach and speed to the specific situation. In the merger of two German Landesbanken, for example, one of the guiding principles defined by the Board at the outset was “integration before optimization”. The idea was to postpone optimization initiatives in order to speed up the integration and avoid disruption to ongoing operations.

In banking mergers, taking critical decisions upfront includes choosing the future IT platform, in addition to taking the key decisions necessary for all successful mergers: announcing the high-level organization structure, determining the desired degree of integration and nominating the top management team.

In any efficient organization, it is difficult to invest your best resources in a project that is not contributing directly to the business. But managers who have led major integration projects agree that this is perhaps the most important requirement for merger success. Having said that, it is equally important to keep your eyes on the ball, i.e. to ensure that business development, customer service delivery and operational excellence are not compromised during the integration process. While merging banks are changing logos, introducing new branch concepts, streamlining product portfolios, and re-arranging sales forces, their customers will watch performance very closely and may turn their backs if their expectations are not met. At the same time, competitors will step up their efforts to lure away the banks’ best customers and merger value may be destroyed even before the first synergies are captured.

To convert synergy potential into real value, integration teams must translate the opportunities identified into action. Only when redundant IT systems are shut down, duplicate branches closed and staff in overhead functions reduced, is it possible to capture synergies in the bottom line.

It may be common sense but cannot be repeated often enough: communicate! Managers and staff, customers, suppliers and service providers, shareholders and regulators – all have questions and worries about how they will be affected by the merger. In addition to one-way information, personal meetings and other two-way channels are an indispensable means of understanding the mood of stakeholders and giving them a sense of involvement. Lack of communication can put the entire merger at risk.

Finally, in banking organizations, which rely so heavily on smooth interaction and cooperation, addressing the cultural differences is paramount to avoiding disruption to service, maintaining effective risk management and capturing synergies from cross-selling.

Looking ahead: M&A is here to stay

The banking industry is far less consolidated than many other industries. However, the global financial crisis can be expected to increase the rate at which further consolidation takes place. Our research of the European banking market leads us to conclude that within the next three years, as many as ten of today’s top 50 banks will have disappeared. At the end of 2008, several deals among the top 50 European banks (by market cap) had either been announced or were rumored. In addition, six of the top 50 banks had lost more than 80% of their end-of-2007 value.

Banking consolidation in Germany is finally gaining momentum. We can expect to see cross-border acquisitions of local champions in small home markets in the Nordic region, Austria and Benelux. Further value chain restructuring and unbundling of distribution and “production” will also generate more deals.

In other industries, national champions in emerging markets, such as Russia, China and India, have begun to acquire established Western companies. Commerzbank was able to fend off Chinese bidders and secure a deal with Dresdner, but Chinese acquirers will surely return at the next opportunity. In the same vein, Deutsche Bank recognized that it needs to become more active in M&A in order to prevent Postbank becoming yet another German bank acquired by a foreign competitor.

The winners of tomorrow are likely to be the anti-cyclical buyers of today, as the savings and loans banking crisis back in the US in the late 80’s / early 90’s proved. But whether the next M&A wave will create real value depends on how well the merging parties perform in the merger decathlon. Only those that excel in the ten key challenges can expect to secure true growth in value.

Lessons from the 1980s

In the late eighties, the US faced a severe banking crisis, triggered by unexpected price drops in the real estate markets, under-secured mortgages and unprofessional management of interest rate risk. Record losses and weak equity ratios among the banks saw the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) foreclose some 1,700 savings & loans associations. In 1989, the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) was founded to sell off the partly insolvent entities. As a result, between 1989 and 1991 alone, 843 banking mergers and acquisitions took place at a value of US$21 billion.

An Arthur D. Little study, which measured the cumulative stock returns around the announcement dates of the buying banks, found that the stock prices of the acquired banks almost always increased. The buyers ́ prices usually developed between -40% and +20% and remained stable on average. The smaller the target bank relative to the acquirer, the more likely the merger was to succeed, since cultural integration and management control could be achieved more quickly.

Mergers within one state were more successful than mergers with banks in another state. However, where acquisitions were supported by the RTC market-entry mergers into other states were clearly the best deal. The mergers that produced large regional and super-regional banks with balance sheets of around US$30 billion were most successful because they provided scale efficiencies.

The stronger the balance sheet, the more successful the new bank was. The smaller the control premium paid upfront, the more successful the merger proved to be. So good negotiation and solid evaluation paid off. The more shares the buyer’s management team held, the more successful further acquisitions were likely to be.

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter