Publications Come Together: Surviving — And Thriving — After A Merger

- Publications

Come Together: Surviving — And Thriving — After A Merger

SHARE:

By Lynne Weedall, Neill Whittaker – KPMG Boxwood

Introduction

Businesses merge for many different reasons. Whether it be to increase market share, diversify into different markets, acquire new capabilities, achieve greater scale, reduce costs, respond to changing market dynamics, or purely and simply survival, mergers are usually driven by a strong and compelling rationale.

And sometimes, it works. Disney Pixar and Exxon Mobil are outstanding examples of mergers that created something bigger – and better – than the sum of their parts.

In the U.K, the merger of Dixons and Carphone Warehouse (which we are very proud to have been a part of) is widely held to have been a huge success. In its first full year the merged business recorded a 21% increase in profits, delivering significant shareholder value in the process.

But success stories like these are much more the exception than the rule. All the research indicates that most mergers and acquisitions fail, with different studies putting the failure rate at between 70% and 90%. It’s also estimated that at least half actually destroy value – the AOL / Time Warner and Daimler / Chrysler mergers are among the best known cautionary tales.

Many, such as the proposed merger between AG Barr and Britvic, never make it over the line – but still manage to chew up significant amounts of money and management attention.

The statistics provide little comfort for chief executives considering tying the knot with another business. But while the risks of failure are high, the rewards for success can be enormous.

In this paper, we have drawn on our experience from Dixons Carphone and elsewhere to explore what makes mergers so difficult – and more importantly, what makes a happy few succeed.

Emotion, emotion, emotion

Any change is hard, but a merger is perhaps the most difficult organisational challenge of all. What makes it so challenging is the sheer level of emotion in the system.

Many people have a significant emotional investment in the organisation they work for. But during a merger, many of the things that drive that emotional connection – colleagues, careers, financial security, shared values and a sense of belonging – are put at risk. That can lead to overwhelming feelings of regret, loss, sadness, anger, betrayal, loss of confidence and depression – all powerful emotions that can be difficult to manage and cause people to behave in strange and different ways.

That’s why being in the middle of a merger is like being in an alternative reality – the normal rules don’t apply. Nothing seems the same – because nothing is the same.

Everything is uncertain – office locations, job titles and roles, reward systems, organisational structures, culture and values, the people you work with – they’re all up for discussion.

What used to work no longer works, and things that were easy become hard. Processes that used to be well defined, like how things got approved, how profit was defined, how your performance was measured, and more, become a source of frustration as the two organisations struggle with the day to day details of coming together.

What’s more, it’s likely to get worse before it gets better. At the start of the process the focus is overwhelmingly on the benefits a merger will bring – but as reality sets in, a gradual disillusionment typically sets in. A number of promises and assumptions are made in the push to get the deal over the line. But the promises often turn out to be not quite what they seemed to be, assumptions don’t hold up, and the market evolves. Gradually the initial goodwill disappears, and suspicion and distrust take its place.

Under pressure, both organisations tend to go back to what they know. Sooner or later, one side usually emerges as the dominant partner – and the ‘merger of equals’ starts to feel more like a takeover. When that happens it can be very hard for people from ‘the other side to accept’ – and a major obstacle to moving forward. So what does it take to succeed?

Lessons from the frontline

In most mergers, the focus is on the most visible things such as where the head office will be, which accounting system will be adopted, structures and reporting lines, and branding. But in our experience, what you can’t see is equally, and often more, important.

Anyone who has been through a merger knows it is a rollercoaster ride. At different stages people on both sides will experience excitement, fear, uncertainty, motivation, disillusionment, loss, resentment, hope, anger, loss of confidence and in worse cases even depression.

The magnitude of the change, and the level of ambiguity people have to deal with, can make it an overwhelming experience. It can be unsettling for many, as it creates a huge amount of emotion in the system – which in turn, can lead to loss of engagement and a significant impact on performance. On the other hand for some the emotion can be one of excitement and opportunity.

These ‘unseen’ aspects are often insufficiently acknowledged or managed, yet they can make or break a merger. Here are some observations from our experience ‘in the trenches’ that can help increase the chances of success.

1. Look beyond day one

Most merged organisations fail to think much beyond day one, because an enormous amount of work goes into just getting to that stage. But day one isn’t the finishing line – it’s just the beginning. If you don’t hit the starting line ready to go with a clear idea of how you will keep the momentum going, you run the risk of losing it – and once it’s gone, it’s very hard to get back. At Dixons Carphone, for example, at a very early stage the leadership team had been announced, key branding decisions had been made and a number of merged stores had been opened. All of these actions provided a very clear statement to both customers and staff which helped generate a huge amount of momentum.

“A huge amount of effort goes into getting the deal done and getting to day one. So when you get there, people are tired and want to breathe – but the reality is that the hard work only begins once the bunting has come down.” – Lynne Weedall

2. Be prepared – but be prepared to change

It’s vital to acknowledge from the start that mergers are a journey – and the end destination may not be what you thought it was when you started out. It’s messy and uncertain, and things will change. Understanding that makes the process much easier for both leaders and staff.

In practical terms, that means building flexibility into your planning. Focus on the first six months – agree what will be done in that time and define an interim ‘end state’, which takes the new organisation far enough to help people ‘let go’ of their attachment to the current state. After that, planning should be directional only, as there are too many uncertainties – don’t set yourself up to fail.

Wherever possible, chunk work into distinct phases as much so your people can see progress being made. 100-day plans are good. Set up a plan-do-review-celebrate cycle to make a very big task seem less formidable and keep your team motivated.

3. Lead from the top

Leadership, of course, is always key – but in a merger strong, committed and visible leadership is absolutely vital. In particular:

• Lead by example: Organisations behave like their leaders, so it’s important that they are open and transparent. It’s also important that they set an example by playing nicely with each other. Ideally, the combined leadership team should agree on a code of behaviour to be upheld at all times during the merger process (and afterwards). Time should be set aside to support leaders with the change they are going through – programs like building resilience and 121 coaching really help.

• Prioritise: While their workload increases exponentially during a merger, top leaders in particular need to be as visible as possible. Ruthless prioritisation is essential – as is ‘backfilling’ some key roles to minimise disruption to BAU.

• Reduce uncertainty: At management level there are usually significant levels of duplication, and uncertainty about the future. Left unchecked, this can pose a major risk to BAU and even to the value of the deal. To avoid this act quickly to clarify singly points of accountability, reduce duplication and conflict between similar roles, and reassure and retain key staff. ‘

• Look to the future: The new world may require different behaviours and skills to the old. Investing in re-skilling and at times re-hiring the right skills for the new world is key.

“Two key factors are likely to be out of kilter in a merger situation: the need for the leadership team to define an end state to provide clarity and direction, versus the leadership team going on their own change/strategic journey where their individual and collective thinking may evolve considerably. The challenge is to have sufficient direction and buy-in for the new team to take the first few steps together – things will then evolve but they will be evolving together.” – Neill Whittaker

4. The ‘soft’ issues are every bit as important

People issues are almost always underestimated in mergers. For example, they are rarely or never a part of the due diligence process, but they pose just as much of a threat to success as any other factor. Given the level of emotion that will be in the system, people issues need to be given much more visible and up front attention than they typically are.

Here are some examples of ways of managing the ‘soft’ issues that we found useful in In the Dixons Carphone merger:

- Tools such as culture surveys and change readiness assessments can be useful in undertaking ‘emotional due diligence’ and making the change process smoother.

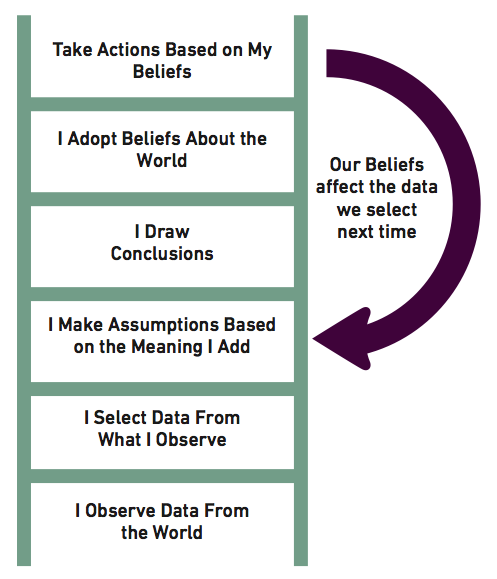

- Helping people understand the process of change is important. There’s a tendency to think that everyone understands this but it’s a very different story when it’s happening to you. Concepts like the ‘trapeze’ model of change are useful to help people understand that ‘letting go’ is difficult and understandable – but it’s necessary to get to the other side. In our experience, the use of existing coaching relationships also worked well in building resilience, as there was already a high level of trust in the relationship.

- ‘Committed listening’ is much more important than ‘committed talking’. Everyone has their own baggage and prejudices, and leaving them at the door is not easy. But for leaders in particular, making the time to listen to other perspectives without pre-judging them is key to bringing the organisation with you.

5. Work it out together

Our experience is that the further away people are from Head Office and the centre of power, the easier the process is. That’s because the closer you are to customers, the less time you spend on theoretical solutions and the more time you spend on simply making it work at a practical level.

For example, the ‘Store within a store’ process at Dixons Carphone got frontline staff from both sides together to figure out how a new, merged store would actually operate – and how we could provide customers with the best possible service. It was highly successful and resulted in a number of merged stores being open on day one, which was a powerful symbol to our customers, our staff and our stakeholders.

The lesson from that experience is that where possible, building culture and capability by delivering is a much more effective option than endless and time consuming analysis.

“The more you focus on the ‘new world’, and what you will build together, the easier it will be for people to let go of the old” – Lynne Weedall

6. Rip the plaster off

Uncertainty is anathema in a merger – so fast and decisive, rather than careful and considered, is a fundamental principle.

The reality is that you only have a small window of no more than 12-18 months to realise the key benefits of the merger before other things get in the way and momentum wanes. You simply need to get on with it.

The key is to act fast and iterate. There is always too much to do, and lots of preconceived ideas and held beliefs that can act as a huge anchor – if you let them. While it may be easier to delay some of the more difficult decisions and changes until later, it only increases uncertainty and prolongs the process of accepting that the world has changed. There is always a price to pay for change, and the longer you leave it the more you have to pay. Ripping the plaster off a wound hurts – but it only hurts once.

It’s important to enable clear and decisive decision making by identifying a single point of accountability for key areas as quickly as possible. And in an inherently volatile environment, be prepared to learn as you go, and don’t be afraid to change course if you need to – but do it quickly.

“There is always a price to pay for the change – and the longer you leave it, the more you have to pay. It is easy in a merger environment to put things off until later – but you will pay so much more in the end.” – Neill Whittaker

7. Get off the dance floor and onto the balcony

‘Getting off the dance floor and onto the balcony’ was a phrase we used often in the Dixons Carphone merger. It referred to the need to take time out every so often to recognise and enjoy what we were achieving along the way. In our experience, informal or spontaneous ideas can work much better than highly planned ‘set-piece’ teambuilding events. For example, one of the things our executives did to was to to on a skiing trip together. There was no formal agenda – it was just an opportunity to get to know each other in a relaxed, informal atmosphere, and it played an important role in bringing the group together as one team.

Building new stories together is an important way to speed up the transition from two separate companies to one new company – so take time out to build those stories along the way.

8. Get the city monkey off your back

Expectations will be high and the city will be watching what happens with interest. The key is to under-promise and over-deliver – and not the other way around. It’s important that you don’t lose sight of business as usual during the process. Separate out the integration from BAU as much as possible, and give serious consideration to backfilling BAU roles to allow key resources to focus on the integration without damaging the core business. And as we’ve already noted, the window for achieving the stated benefits of the merger is a small one, so speed and relentless focus are critical to the integration project.

9. Be very, very sure

Mergers can have a big upside – but they can also be very painful and a massive drag on the business. That’s why the rationale for a merger needs to be absolutely clear and compelling. To go through the level of disruption that a merger brings with it, you need to be very sure that it will create real value for the business.

Your people need to be very sure too – and a key part of the leaders’ role is to help them understand why it’s necessary. ‘Letting go’ of the old organisation is a leap of faith, and your people need a very good reason to do it. Our experience at Dixons Carphone proved that when the going gets tough, having a compelling rationale that your people buy into is what will get you through it.

“The potential loss of talent, goodwill and engagement through a merger process can be huge – so the upside must be huge too. It can’t be marginal; it has to be truly transformational.” – Lynne Weedall

Final thoughts

Mergers are challenging. And given the failure rate, it’s fair to wonder why anyone would consider undertaking one. The answer, of course, is that successful mergers can add enormous value to both parties. When they fail to deliver value, the problem is not usually with the business case, but with the execution.

Many of the principles that underpin successful mergers are common to all successful organisational change – clarity of vision, visible and committed leadership, communication, support and collaboration. The difference in merger situations is that the level of uncertainty is often even higher, timelines are often compressed timelines and there is an increased sense of urgency.

But while all of this creates increased pressure, perhaps the key issue is one of perspective. Mergers are often approached from the viewpoint of structures and processes. The focus is on getting the organisation structure right, getting the branding right, and getting the IT and finance processes right. But while those are all important, in our experience the key – as always – is getting the people issues right.

Appendices

Appendix 1. The Integration

Management Office

Creating an effective Integration Management Office (IMO) is key. As well as providing the project management to keep the integration on track, it should also act as the source of key skills and expertise.

Roles in the IMO should include:

• An IMO lead

• Project support / administration

• Rewards expertise

• Legal / policy expertise

• Culture / leadership resource

• Communications specialist

• Analysts

• A consultation / redeployment team

• HR business partners (at a ratio of around 1:100)

Experience is critical. Mergers are challenging, and ideally the IMO should be staffed by people who have ‘been there, done that’ and can provide practical knowledge and experience in similar situations.

Another key attribute for the IMO is independence. In a highly charged (and sometimes tribal) environment, independence is crucial – but it can be difficult if not impossible to be seen as truly independent if you come from one side or the other. In our experience he use of external consultants with the right skills and experience can be an effective way to bring not only an outside perspective, but also an independent one.

Appendix 2: Observations on the role of HR in mergers

HR has a pivotal role to play in supporting both the business and staff through the merger process. Here are some personal observations on the unique challenges for HR practitioners:

• Look after your own journey. The HR team will be going through it’s own change curve while simultaneously trying to support other people through theirs. It’s a difficult juggling act, which makes it even more important to provide adequate support to enable the HR team to function effectively. Resilience building, change management interventions and team building initiatives can all help.

• Reward Management will be a particular challenge. Harmonising reward systems is always one of the most contentious areas. Expect it to take much longer and require much more resource than you imagine, and resource accordingly.

• Baselining is no picnic either. In fact anything to do with data will also be harder and more complex than you expect, and having a skilled, key resource is essential. But getting it right is key to capturing synergies and measuring success.

• Functional integration is not just a structure exercise. While it’s easy to get caught up in org charts, functional integration is much broader. It’s about understanding how work will actually get done and what actually happens in the system. For that reason, it’s essential to involve finance, IT, the business and operating model specialists as well as HR.

• Ring fence integration resources – particularly key functions like legal, reward and resourcing.

• You cannot over-communicate. Open, adult and regular communication is absolutely essential.Don’t underestimate how much communication is required, or how important it is – especially amongst the leadership. Every nuance will be scrutinised and used to validate or challenge assumptions.

• It needs to come from the top. A dedicated and very credible cultural lead is crucial to success, and so is strong and committed CEO sponsorship.

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter