Publications Avoiding post-merger blues

- Publications

Avoiding post-merger blues

SHARE:

By Ralf C. Schläpfer and Gustav Baldinger. – BearingPoint

Cultural differences pose serious business risks for any company engaged in merger and acquisition activity. Alexa Fletcher, BearingPoint research fellow, identifies five management priorities that corporate leaders should focus on to help reduce these risks and enhance returns.

In 1998, Daimler-Benz bought a highly profitable U.S. automaker—a company enjoying record sales of light trucks, vans and large sedans. In as few as three years later, Chrysler was hemorrhaging money. Market capitalization of the combined DaimlerChrysler had not budged and expected synergies with its new German parent company were nowhere to be found. “What happened to the dynamic, can-do cowboy culture I bought?” lamented former Daimler CEO Jürgen Schrempp.

What happened, according to numerous observers, amounted to a textbook case of cultural misalignment. Chrysler had long seen itself as a bold innovator of vehicles for middle-class Americans and a plucky survivor of four brushes with near-bankruptcy. (Call it water.) Daimler, by contrast, stood for uncompromising quality and disciplined German engineering. (Oil, meet water.)

The two companies distrusted one another from the start, to the point that some Daimler executives publicly vowed that they would never be seen in a Chrysler vehicle. Distrust likely fueled the business woes that faced the partnership, such as the fierce resistance by Daimler executives to link product development across the two organizations. One analyst observed that the merged organization operated like two independent companies that simply added together their numbers on the balance sheet—and not much else.

The cultural divide was reflected not only in the two groups’ products but also in their management styles. Daimler-Benz fostered a formal, highly structured work environment; Chrysler took pride in its more relaxed, freewheeling approach. Not surprisingly, as Daimler asserted dominance over the combined companies, Chrysler began a steep downturn, with widespread departures among key executives and engineers, growing discontent among the rank-and-file, and mounting hostility between Stuttgart and Detroit.

After nearly a decade of organizational turmoil and plunging profits, Daimler sold its Chrysler division in May 2007, formally dissolving a union hailed as one of the worst mergers in history.

The same sad story plays out time and again in the aftermath of large—and small—scale corporate mergers. Although companies see merger and acquisition (M&A) activity as an essential means of growth and innovation, some 55 percent to 77 percent of completed M&As fail to meet the strategic and fiscal objectives that initially justified the deal.

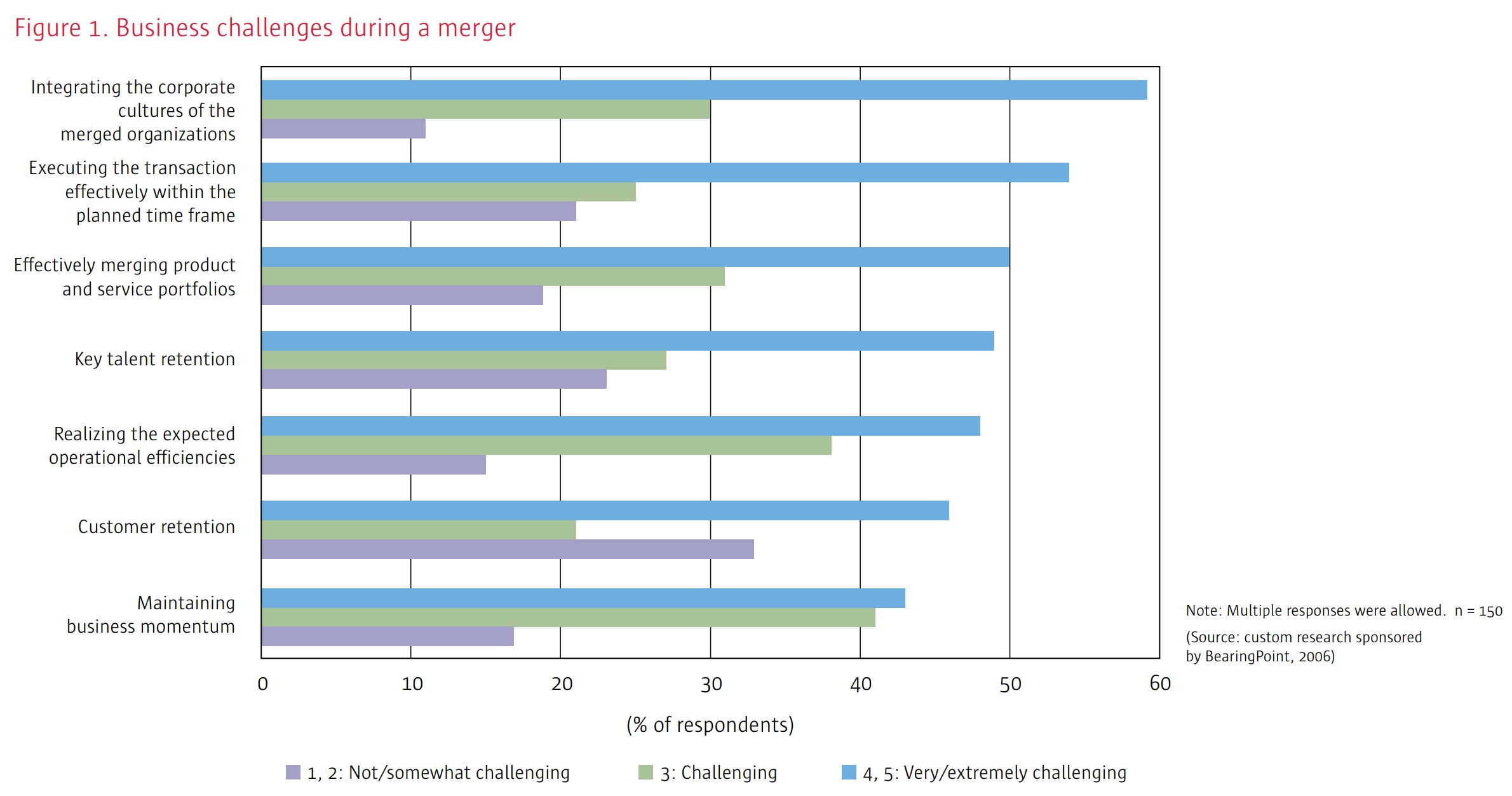

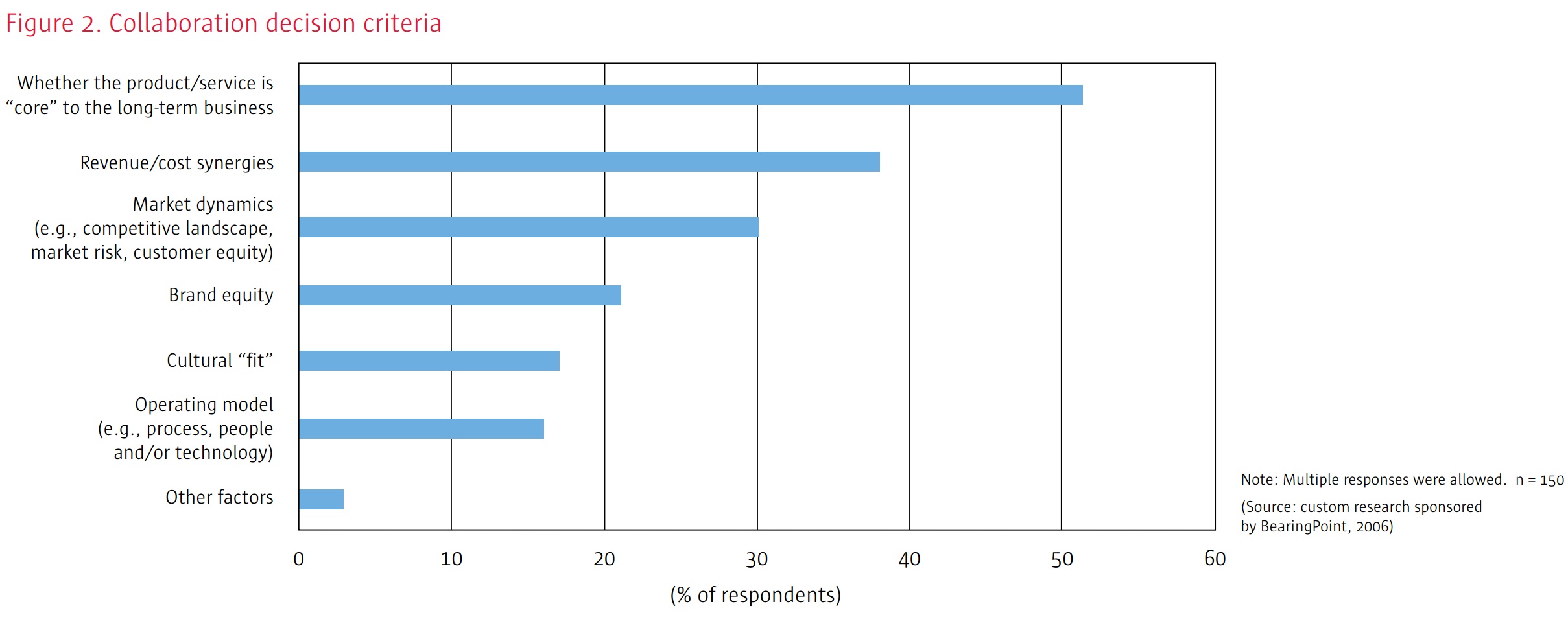

In a survey commissioned by BearingPoint, 150 C-level executives in multiple industries were asked about the most significant business challenges they faced during a merger. Cultural integration ranked at the top of the list (Figure 1), yet respondents admit that it’s among the last things they consider when deciding whether to attempt a new merger, acquisition or alliance (Figure 2).

Spotting cultural land mines

Cultural differences may appear subjective and difficult to measure, but our research and experience suggests that it is possible to systematically identify and analyze them. There are five key areas of potential cultural incompatibility that, left unattended, are likely to create business risk for organizations merging or forming new partnerships. These five key areas of concern are:

- Leadership

- Governance

- Communication

- Business processes

- Performance management and reward systems

Unlike most cultural integration frameworks that focus solely on issues of leadership, communication and incentives, our framework is more operational. It helps leaders specify potential points of friction in business processes and governance models. Organizations that actively manage their corporate cultures should focus on these five areas as early as possible in the merger, acquisition or alliance process. At the same time, they can work with their new partners to develop cultural integration strategies that help both companies resolve key differences effectively, thereby reducing the associated business risks.

By taking a proactive, disciplined approach to cultural integration, companies can accelerate the integration process and realize the transaction’s inherent benefits more quickly. In one highly successful example, a large multinational conglomerate entering a Korean joint venture organized a series of executive workshops, beginning with an introduction to Korean business culture. The process culminated in the design and establishment of a carefully structured approach to determining the venture’s governance, human resource and communication practices. The workshops provided a critical venue where members of both management teams could discuss potential areas of cultural incompatibility and consider how best to address them. As a result, the venture moved forward with minimal conflicts and exceeded first-year revenue expectations.

Alternatively, companies that ignore cultural issues during the pre-merger and integration planning phases of a deal often wind up reacting to these issues in impromptu fashion, sometimes destroying much of the merger’s potential value in the process. In the case of DaimlerChrysler, the $36 billion merger brought together the world’s most profitable and cost-efficient carmaker at the time (Chrysler) with the world’s premier luxury carmaker (Daimler). News of the “merger of equals” that was expected to create a global automotive powerhouse got investors’ attention, nearly tripling both companies’ stock prices. Yet, the clash of these companies’ cultures, paired with the exodus of Chrysler executives who built the big profits and products of the 1990s, left DaimlerChrysler with a chaotic American operation, a plunging stock price and billions of dollars in losses. Only two years after the merger, the combined company was worth less than Daimler-Benz had been before the merger.

Conflict area no. 1: Leadership

As with DaimlerChrysler and numerous other less-than-successful business alliances, leadership compatibility issues can be paramount. One company’s executives may favor a command-and-control style, whereas leaders at the other organization prefer a more hands-off approach. Indeed, every company’s leadership style can seem unique. However, when senior leaders sitting at the same table motivate their staffs and resolve conflicts in diverse ways, the resulting friction often creates additional risks—for example, a lack of commitment to new company goals on the part of middle managers or a high level of turnover among key employee groups.

Despite the qualitative nature of such differences, companies can begin identifying areas of incompatibility in leadership practices even before the deal is closed. They can pose the right questions to company leaders, senior staff and mid-level managers—on both sides of the fence—and then compare the results. For instance, “How do leaders in your organization drive and assess results?” “What types of leaders tend to advance in your company?” “How would you describe the leadership style in your organization?” “When differences of opinion exist among senior staff, how are these differences resolved?”

Conflict area no. 2: Governance

As recent events have illustrated, effective corporate governance requires much more than a system of checks and balances to protect stakeholder interests. It must encompass the way decisions are made in each part of the company and across organizational boundaries. This includes the work of such governing bodies as program management steering committees, councils that oversee the work of support functions, corporate governance boards and even new product development committees. At the same time, however, corporate governance is about people and the way individual leaders make and carry out decisions within each organization.

Conflict area no. 3: Communication

Communication, an essential task of leadership in any organization, is critical during a merger given the inherent uncertainties on the part of employees and customers. However, communication styles vary widely among companies, and what has worked for one may not work for another. Attitudes about confidentiality, preferences for formal versus informal channels and the frequency of communications may all come into play.

With employees in particular, insufficient or inconsistent guidance on such key issues as organizational restructuring, customer relations and changes in financial policies can create unnecessary business risk. By anticipating these risks well in advance, the acquiring company’s leadership can decide whether to invest in proactive integration tactics, such as the use of two-way communication channels, that can be leveraged to reinforce values, goals, policies and procedures throughout the organization.

Conflict area no. 4: Business processes

Companies in the throes of a merger invariably seek ways to realize new efficiencies through integrated functions and procedures. They may consolidate plants or branch offices, centralize purchasing to leverage their buying power or consolidate back-office functions. No matter how necessary these changes, however, they almost always entail the adoption of new business processes that may themselves become sources of contention.

Besides different leadership styles, governance models and communication preferences, most companies also have distinct ways of developing, updating and enforcing core business processes, which must be understood and respected during the integration phase. Changes in the way companies handle these tasks require strong leadership, supported by careful and frequent communications to verify that employees, customers and vendors understand and accept them. If changes in core business processes and process interdependencies are not deliberately and systematically thought through during the integration planning phase, organizations risk internal breakdowns in the quality of products and services and may provide incorrect or untimely data to customers, suppliers

and service providers.

Conflict area no. 5: Performance management and reward systems

It hardly needs saying that people in companies yoked together in a merger can resent their new colleagues in comparable positions who are receiving significantly more compensation or recognition. Differences in the way the acquiring and target companies evaluate and reward employee performance are important and, if overlooked, can lead to morale issues, undesired turnover, inconsistent performance and a decline in overall employee productivity.

Thus, merger integration plans should include efforts to harmonize performance metrics and compensation systems where possible, while explaining important differences when necessary. Newly merged companies must help employees understand that their different recognition and reward systems are fair, even if not always uniform across the organization.

Disparities in sales incentive systems can create particularly sticky problems. The issue warrants close attention because the loss of key sales staff can also mean the loss of important customer relationships, which can immediately affect the company’s value. Even outside the sales group, however, incentive systems are tied closely to employee retention.

If a design engineer working on product development receives incentive payouts less frequently than his new co-workers, he may decide quickly that the grass is greener at a competing firm, taking his great ideas—and some of the firm’s intellectual capital—with him as he walks out the door.

Determining the scope of your cultural integration effort

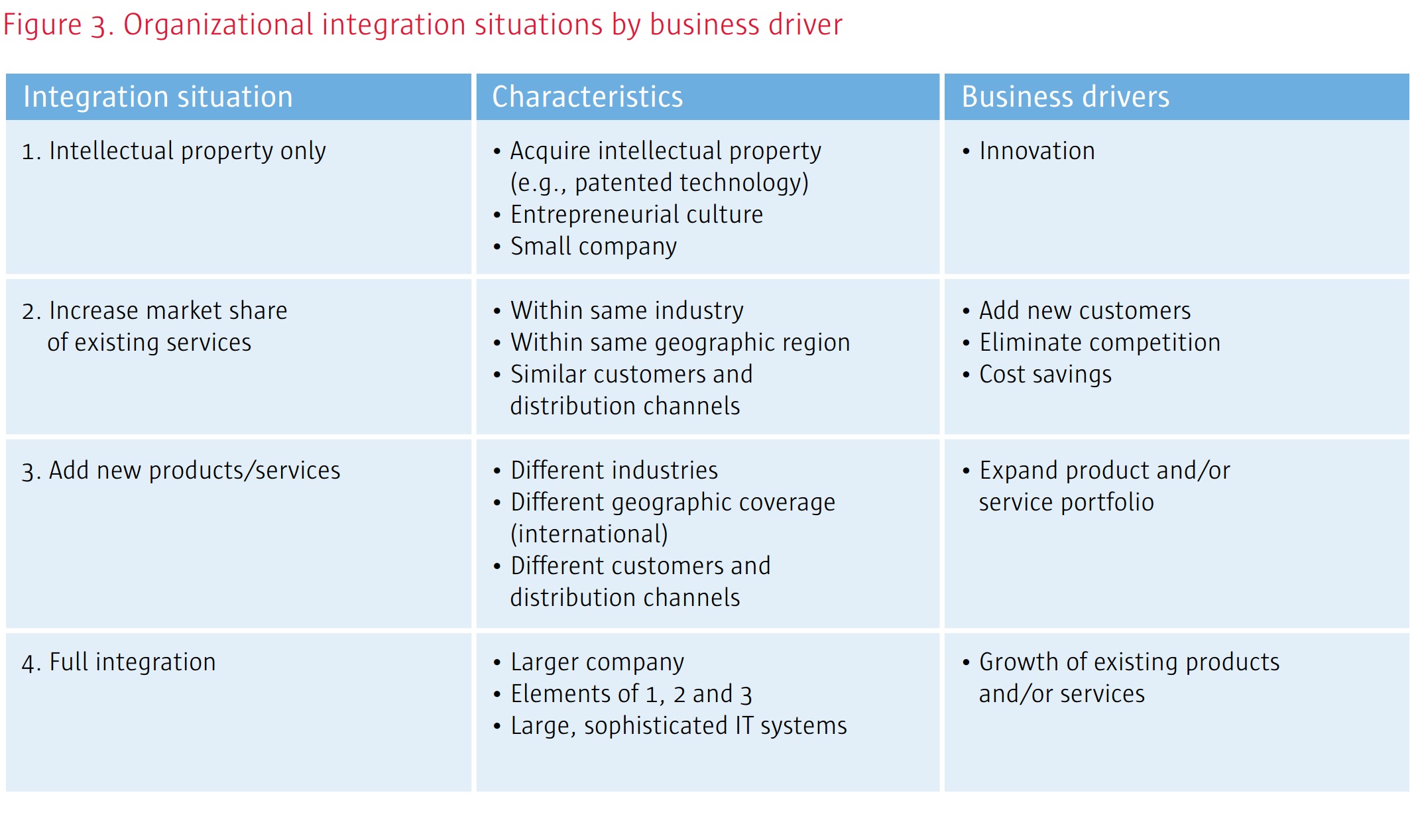

Most companies pursuing growth through M&A activity understand that the success of each deal depends on numerous factors—such as business drivers, relative size of the target, prevailing market conditions and financial considerations. They also know that different approaches to growth entail different organizational integration challenges, each with distinct cultural implications. As the scope of the integration effort increases, so do the potential incompatibilities in each of the five areas identified.

For example, if a company is being purchased solely for the purpose of obtaining its intellectual property (Figure 3), the transaction may require limited cultural integration or none whatsoever. However, if the acquiring company’s goal is to expand its portfolio of products and services, the extent of the integration effort will be broader in scope because of the potential for cultural conflict in multiple areas. Given the high probability of cultural derailment during the merger integration process, corporate leaders should begin to assess the scope of the cultural integration effort as early as possible.

Evaluating cultures before the deal closes

In a few instances, companies engaged in ongoing M&A activity incorporate cultural evaluation criteria into their overall model for assessing potential targets. Division leaders within a large, diversified technology company, contemplating whether to pursue the acquisition of a profitable, family-owned high technology firm, contracted for a preliminary cultural assessment—with their target’s consent. As a result, they determined that full integration, including changes to the firm’s existing organization structure and human resources processes, could impact employee productivity and retention significantly. Instead, they decided to pursue minimal integration and serve primarily as “stewards” in the new relationship, an approach they felt would lower their risk and preserve the deal’s value.

In our experience, opportunities to complete a meaningful cultural assessment during the acquisition strategy phase are often limited. However, openings to pursue this work during the due diligence phase are frequently overlooked. To effectively take advantage of this window, the executive team initiating the transaction should complete a self-assessment before due diligence begins, using a questionnaire designed to capture organizational information around each of the five areas identified. With this self-assessment in hand, executives can use the due diligence period to solicit the potential new partner’s responses to the same questions. This step is critical because most important cultural information cannot be gleaned from documents or spreadsheets; it can only be elicited through dialogue with members of the other company’s leadership team.

Based on the information gathered from both organizations, a cultural compatibility profile can be created, identifying both similarities and differences between the two organizations in each of the five areas. This profile can highlight areas where significant differences exist, along with the business risks that might arise if incompatibilities are left unaddressed. These risks can vary greatly and may include executive turnover, faulty internal decisionmaking processes and the loss of key customer relationships.

Key findings from this preliminary cultural assessment should be included in an initial due diligence report and circulated for review and comment among members of the executive team initiating the transaction. It’s important to note that these findings will need to be validated further with a broader audience, should the deal close, when the overall integration planning process begins.

A cultural compatibility profile can highlight areas where significant differences exist, along with the business risks that might arise if incompatibilities are left unaddressed.

Once a team has been named to lead development of the overall cultural integration strategy, work can begin to define and implement the initiatives needed to address areas of significant cultural incompatibility.

Moving from assessment to action

Once both organizations get the green light to move ahead with integration planning, their tasks become more daunting. Typically, the process includes executive-level work sessions where results of the initial cultural assessment can be shared in confidence with senior team members. Key outputs from these facilitated discussions should include:

- Possible revision and, ultimately, validation of the cultural compatibility profile.

- Confirmation of the associated business risks.

- Risk prioritization and definition of related business impacts.

- Identification of the core team responsible for leading the development and implementation of the overall cultural integration strategy.

The approach taken by a defense electronics company that recently oversaw business unit integration in multiple European locations provides a good example of how these sessions can work. Through a series of carefully crafted executive workshops, members of the new leadership team created a shared vision for the organization, including a common platform for new product development. They explored differences in leadership style and strategies to manage them—no small task, given the different nationalities seated at the table. Finally, they worked together to create and deliver a set of key messages for their new organization, a step that was immediately visible to employees and helped pave the way for subsequent integration efforts.

Once a team has been named to lead development of the overall cultural integration strategy, work can begin to define and implement the initiatives needed to address areas of significant cultural incompatibility. These might range from establishing processes to delegating responsibilities clearly during the integration phase to defining how to transition effectively to a common sales incentive plan. Regardless of the initiative, executives should make sure it’s designed to help the new organization mitigate an identified business risk effectively. Each initiative’s results should be measured by this standard as well.

Cultural integration issues pose significant business risks in any merger, acquisition or joint venture. Looking out for these risks at the earliest stages of the deal process, however, can help business leaders greatly improve the odds that the transaction will create, rather than destroy, shareholder value. Through careful planning and prioritization, they can better manage the human side of business integration—a risk that will probably never go away completely, given the complex dynamics of people in every organization.

First steps

Regardless of whether you’re a CEO of a large company considering the acquisition of one of your suppliers or a human resources executive ready to embark on a due diligence effort, here are four steps that you can take today to help your organization reduce culturally driven business risks going forward:

- Don’t underestimate the business impact of cultural differences—they can make or break the transaction. For many professionals, cultural integration work is at best unfamiliar territory. Beyond the obvious risk of unwanted turnover, the connection between cultural differences and other forms of business risk isn’t always clear. These factors contribute to the tendency to underestimate the business impact of cultural conflict. Because cultural incompatibility can erode or destroy shareholder value, it’s wise to spend time upfront to learn more about this topic and how to approach it.

- Start the cultural analysis process earlier rather than later—preferably before the deal is proposed. By taking stock of potential cultural differences early on, your leadership team can gain insights to help move forward critical conversations with a potential partner more quickly. This intelligence can also help lay the groundwork to shape integration strategies before closing the deal, rather than starting from scratch once the ink is dry.

- Synthesize cultural integration tasks with the overall work effort. During the target identification, due diligence and integration planning processes, try to integrate culture-related tasks into the overall work effort as much as possible instead of treating them as separate, stand-alone responsibilities. This can help avoid unnecessary duplication of effort and allow your colleagues to leverage cultural insights on a real-time basis for their teams.

- Develop initiatives with clear outcomes in mind—and measure the results. The initiatives you develop to address cultural differences should be designed with clear, measurable outcomes in mind that can help mitigate specific business risks. To verify that these outcomes are achieved, performance metrics should be used to measure their progress on a regular basis. Keeping this in mind helps position your organization to make the right investments in cultural integration work that can deliver real business value.

Companies can work with their new partners to develop cultural integration strategies that help both organizations resolve key differences effectively, thereby reducing the associated business risks and preserving—or creating—business value.

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter