Publications When To Think Alliance

- Publications

When To Think Alliance

- Bea

SHARE:

By David Ernst and Tammy Halevy – McKinsey & Company

In some circumstances, the market seems to reward alliances more richly than mergers and acquisitions. Maybe it knows something that many managers don’t.

Rarely does a day pass when the front pages of the world’s financial publications don’t trumpet the latest corporate alliance. Over the past decade, corporations have transformed themselves from 100 percent owners of their own assets into fuzzy-walled organizations linked with dozens of partners in strategic alliances such as joint ventures, cross-selling agreements, and patent-licensing deals. Alliances are particularly crucial to e-businesses that are in a hurry to access or leverage content, customers, or technology, as well as to all businesses that need to mitigate risk while pursuing growth options.

Our earlier research indicated that alliances have a long-term success rate of about 50 percent, measured in strategic and financial terms. Since the long-term success factors for alliances are well known, smart managers can improve the odds. Nonetheless, the stakes have risen for companies entering into alliances. Besides focusing more and more on short-term performance, investors and analysts are closely watching alliance announcements. Managers should therefore be asking new questions: Do alliance announcements affect share prices? Are these effects correlated with ultimate success? Most important, how can you tell when to use alliances instead of acquisitions and when to use certain deal structures and not others?

To answer these questions, we examined the effect of alliance announcements on the share prices of more than 2,100 companies. This research sample spanned most major countries, all industries, and a variety of alliance structures, including equity joint ventures, contractual alliances, and minority equity stakes accompanied by one or more contractual alliances. Our analysis separated out the abnormal return in the days surrounding each alliance announcement — that is, the change in share price that was not explained by overall market trends (see “How to spot a winner”).

Managers shouldn’t proceed with an alliance without thinking through its implications for share prices.

The results of our analysis, combined with insights gleaned from our wide experience, indicate that it is unwise for managers to proceed with an alliance without thinking through its implications for share prices. First of all, large alliances do move market capitalization. That alone should get managers’ attention. Additionally, we found that alliances are better received than mergers and acquisitions in fast-moving, highly uncertain industries such as electronics, mass media, and software. They are also the preferred choice for companies trying to build new businesses, enter new geographies, or access new distribution channels. Contractual alliances, simple and flexible, are better received by the market than more complicated equity joint ventures. And, finally, when it comes to alliances, it turns out that polygamy pays: multipartner alliances and consortia tend to be quite well received.

Think carefully about your announcement

For large alliances at least, the evidence is unequivocal: they do create shareholder value. Just over half (52 percent) of large alliances caused the share price of the parent to rise or fall by more than one standard deviation of its normal movement, and of these, 70 percent of the price reactions were increases — a “win rate” that is substantially higher than the percentage for acquirers in M&A transactions. (To overcome the usual limitations of data about the size of alliances, we defined large ones as those that created a top-ten player, involved assets of more than $500 million, or included the sale of an equity stake.)

Among alliances as a whole, share prices moved by a comparable extent for only 29 percent of the participants at the time of the alliance announcement, and just half of those were price increases. Since alliances provide a highly tailored way to access capabilities such as specific products or technologies, many deals are small relative to the parents’ overall business and may not provoke much movement in share prices.

Why do big alliances have such impressive success rates? For one thing, big deals attract more scrutiny from the market. They also tend to make companies more likely to invest significant management resources in thinking through the strategy, choosing the partner, developing an appropriate deal structure, and communicating the purpose of the deal to the market.

And managers involved in big alliances tend to follow the lessons identified in this article more often than do managers involved in small ones.

The effects of alliance announcements appear to be a good indicator of longer-term success. Our sample included 25 companies involved in alliances that were extensively covered by reporters and analysts roughly one year later. Analysts and reporters felt that 16 of the partners had fulfilled their strategic and financial objectives in the alliances they had entered; of these, 14 were rewarded with share price increases of more than one standard deviation after the alliance was announced. Commentators regarded the alliances of 9 companies as long-term failures, and 8 of these 9 alliance announcements were associated with a significant decline in share price.

Since the market does respond to alliances and is often right about which of them will create value in the long run, it makes sense to understand how the market arrives at its response. Specifically, when does the market reward alliances over M&A structures? Our evidence suggests that investors and analysts favor alliances for reducing risk and building businesses in turbulent environments as well as for uniting multiple partners. The market also views alliances more favorably when they are simple.

How to spot a winner

As the basis for our analysis, we identified all alliances that were first mentioned in the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and the Japan Economic Newswire from 1996 to 1998. The resulting list comprised 2,050 deals involving 4,583 partners and covering a broad range of industries, geographies, and kinds of alliances. Next, we set aside all deals in which significant information about anything other than the alliance in question (such as acquisitions or earnings) had become public during the period starting five trading days before the announcement and ending five trading days after it. This reduced the list to 2,102 companies that had announced alliances.

Then we used the capital asset-pricing model to determine the change in share price expected for each alliance partner in the absence of any announcement effect, in view of whatever was happening in a major local market index at the time. We observed the price movements of each stock during the 11 days starting 5 trading days before the alliance announcement and ending 5 trading days afterward and subtracted the expected stock price movement (the beta-adjusted market return) from the actual stock price movement. The difference is the abnormal return of each stock — the unexpected component, which contains any market reaction to the alliance itself plus an error term due to random fluctuations. Thus, “abnormal market reaction” is the difference between the actual market reaction to the announcement and the expected market reaction.

We identified a total of 615 winners and losers: companies whose share prices had gone up or down, respectively, by at least one standard deviation during the 11-day period. This standard deviation was based on each particular stock’s random movement over the 90 trading days preceding the 11-day study period. Of the 615 winners and losers, 53 percent moved up by more than one standard deviation and were deemed winners, while the remaining 47 percent moved down by this amount and were deemed losers. The median abnormal value creation for a winner was $560 million on a median market cap of $8 billion; the median loser lost $550 million in market cap. Market successes and failures were distributed across a wide range of alliance types, including nonequity alliances, joint ventures, and equity stakes.

Alliances for change

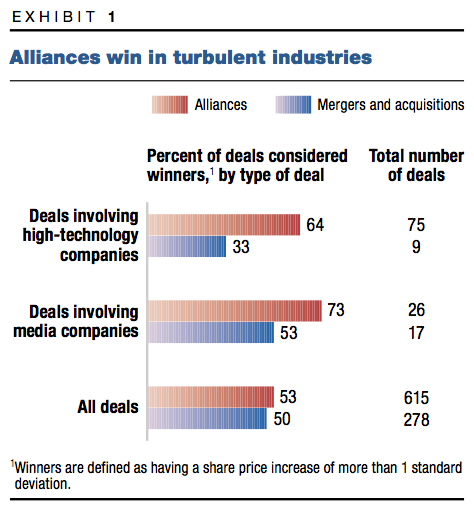

In fast-moving, highly uncertain industries, the market tends to prefer alliances to M&A (Exhibit 1). It rewarded alliances much more richly in electronics, media, and software, for example: nearly three-fourths of the media and entertainment alliance announcements were winners (that is, they raised the announcing company’s stock price by more than one standard deviation), compared with just 53 percent of the acquiring companies in M&A transactions. (In this article, when we discuss returns to M&A deals, we are always talking about returns to the acquirer. The vast majority of alliances are either win-win or lose-lose. By contrast, in many acquisitions the seller gains, while the acquirer often overpays and thus loses share value.)

As technology rapidly transforms the way media companies can reach an increasingly global audience, alliances allow them to leverage their content, enter new geographies, and place several bets rapidly. Why pay an acquisition premium and endure the rigors of postmerger integration when you can get most of the upside by using alliances to leverage intangibles such as content, cartoon characters, and customer relationships? In June 1998, for instance, the US television network NBC announced that it would enter the Internet age through a joint venture with CNET Networks (an Internet media company) to operate the Snap.com portal. Analysts expressed approval, and investors pushed up the stock price of the parent company, General Electric, by more than 4 percent.

Of our sample’s 75 electronics and software companies that made significant alliance announcements, 64 percent were winners, compared with just 33 percent of acquirers involved in M&A transactions in this industry sector. When Displaytech and Hewlett-Packard, for instance, announced an alliance to develop and manufacture display systems for consumer electronics products, HP’s stock climbed by nearly 6 percent and Displaytech’s by more than 17 percent, creating close to $4 billion in value. Likewise, Sony had an abnormal return of 15 percent on a market cap of $33 billion when it announced that it had taken a 5 percent stake in Next Level Communications, a maker of advanced digital-TV set-top devices. (For an example of how critical alliances have become in technology-intensive businesses, see “AOL: Alliances on-line?”)

AOL: Alliances on-line?

To see how important alliances have become in technology-driven industries and how profoundly alliances can contribute to a company’s market value, you need only look at America Online. After fewer than 15 years of existence, AOL has a market value of well over $100 billion ($121.5 billion on August 1, 2000). This startling record of success is attributable, in large part, to AOL’s web of alliances and partnerships, which have helped it become the world’s largest provider of on-line services.

Through a portfolio of partners, AOL gains access to products, content, technology, and global customers — assets that create a network of increasing returns and help explain the company’s prodigious market cap. Each new alliance for content makes AOL more attractive to subscribers, and this in turn attracts more advertisers and content partners.

AOL’s deals have often moved its share price, and many of those deals included in our sample met our definition of winners. In 1997, for example, AOL formed an innovative alliance with Tel-Save to market long-distance service to AOL’s customers. The alliance was received positively by the market.

Likewise, in October 1997, long before AOL acquired Netscape Communications, the two companies announced an alliance to launch a co-branded instant-messaging service. The service notifies users when other registered Instant Messenger users are also on-line. The price of AOL stock jumped by more than 9 percent when this technology-related alliance was announced.

AOL has expanded into both Latin America and Europe through joint ventures. In Latin America, the company entered into a partnership with the Cisneros Group, a winning deal in our analysis. In Europe, a joint venture with Bertelsmann also created significant abnormal value when it was announced.

Alliances for growth

Most of the value created in the US economy in the past decade stemmed from building new businesses rather than squeezing benefits from incumbency in core ones. Alliances for growth can involve new capabilities, new channels, and new geographies.

New capabilities

Building new businesses means assembling a host of new capabilities: products, customer relationships, technologies, and so on. Few organizations, especially those launching e-businesses, can develop these capabilities internally with sufficient speed. Alliances give companies a way to leverage their existing skills while they quickly and flexibly access the capabilities of others. In addition, alliances often involve less capital commitment and risk than do acquisitions — a big advantage in areas in which a company’s management capabilities are unproved.

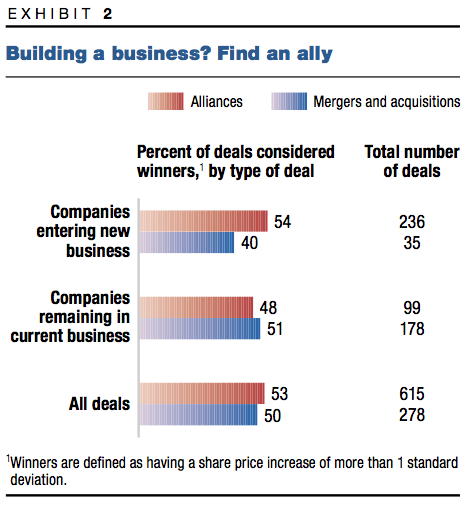

As a result, alliances are generally a preferred vehicle for building a new business. Of the 236 companies that used alliances to do so, 54 percent were rated successes by the market, compared with only 40 percent for acquirers in comparable M&A transactions (Exhibit 2).

The market’s reaction makes sense. When both partners in an alliance are creating a new business, the alliance permits them to share the risk. Nippon Television, Time Warner, and Toshiba, for example, joined forces in a joint venture to produce and distribute digital-TV software on a global basis. The joint-venture announcement was well received by the market.

New channels

Alliances should also be the vehicle of choice for companies seeking to expand sales through new distribution channels. Of the 54 sampled companies that allied in hopes of expanding in this way, 60 percent were deemed successful by the market. When the British bank Abbey National, for instance, teamed up with the grocer Safeway to offer Safeway shoppers in-store financial services, investors responded positively, creating nearly $660 million in value for Abbey National shareholders, or abnormal returns of 4.2 percent. Especially in mature businesses, customer acquisition costs can be much lower for alliances than for go-it-alone strategies.

New geographies

Previous work shows that many companies have used alliances successfully to enter new geographies. Corning, for instance, has used alliances very effectively to enter new geographic markets and achieve a range of other objectives. When the company teamed up with Asahi Glass and Samsung in December 1996 to build a Mexican factory that manufactures glass funnels and panels for color-TV tubes, the announcement was accompanied by a significant share price increase for Corning, which owns 40 percent of the venture.

Networks and consortia

Although lessons about alliances often use marriage as an analogy, the metaphor is flawed: companies are not people, and an alliance that comes to an end is no tragedy. Equally important, companies may benefit from forming multiple or multipartner alliances to meet various needs — not necessarily to the disadvantage of any of the parties.

In particular, multipartner alliances can give their participants targeted access to specific assets of the partners. By contrast, M&A can be highly impractical when three or more partners wish to combine some of their assets; if a two-way merger is costly and disruptive, a three-way merger is more so. And even if the expected benefits of the merger or acquisition are very large, they may pale in comparison with the transaction costs of the deal itself.

Multipartner alliances are particularly attractive for setting standards. The small UK-based software company Psion, for instance, developed an operating system for mobile handheld devices. Psion needed to have its system adopted by industry leaders many times its size. They knew that a standard operating system would stimulate the market for their hardware. So in June 1998, Psion joined forces with Ericsson, Motorola, and Nokia to create Symbian, a joint venture to support the adoption of Psion’s operating system — to the benefit of all parties. The announcement of the joint venture created a combined abnormal return of $10 billion.

Many successful business builders use alliances to put themselves at the center of networks that let them leverage intangible capital

Many of the most successful business builders also use alliances to position themselves at the center of a network in which they can leverage intangible capital without owning many expensive assets. Nokia’s market capitalization, for example, has grown by $253 billion over the past five years. The company has leveraged a broad range of alliances to access manufacturing capacity, to conduct joint R&D, and to make products available to large numbers of customers rapidly. Nokia has joint ventures with Capitel Group in China and Gradiente in Brazil, participates in technology alliances such as Bluetooth and Symbian, and reaches customers through strategic supply arrangements with AT&T, NTT DoCoMo, and Sprint. The announcement of these alliances generally produced a favorable market reception; the Symbian joint venture created nearly $6 billion in abnormal value for Nokia alone.

Simpler is better

Although most of the results of our alliance study addressed situations in which alliances might be preferred to M&A, the study also yielded an interesting bit of wisdom about the types of alliances most favored by the market. After all, a manager’s work doesn’t end with the decision to “do an alliance”; it is also necessary to choose among a variety of structures.

The details of how to structure an alliance are, of course, case specific. Nonetheless, in general the market does seem to prefer simpler and more flexible deal structures. Looking at the alliance announcements that we could classify as winners or losers (that is, ones that were associated with an expected change in the share price greater than one standard deviation), stock prices increased for 68 percent of the companies announcing the sale or purchase of an equity stake and for 56 percent of those forming a contractual alliance involving no equity. But among the joint ventures only 50 percent were winners.

Joint ventures are less well received for several reasons. First, they usually take longer to get going than do contractual alliances. A joint venture is a completely new company, separate from either of the partners and often owning assets contributed by them. It thus requires complex governance structures and a significant commitment of senior management’s time. Furthermore, joint ventures don’t last forever: they have a median life span of seven years, and the arrangements needed to unwind them at the end don’t always go smoothly. So while a joint venture might be the right answer in certain cases, companies considering one should first explore simpler deal structures that capture most of the value at lower cost and with less complexity. Another strike against joint ventures is that analysts often are skeptical of any deal that may complicate the parent company’s future strategic options, and many joint ventures fit this description. After all, a joint venture can compromise the ability to sell a company at a fair acquisition price, and many joint ventures are in fact steps toward a sale to one of the partners.

Therefore, if management wants to proceed with a joint venture — or with a similarly frowned-upon alliance, such as a merger in a fast-moving industry — the announcement should articulate with absolute clarity how the deal fits into the company’s overall strategy. It should also spell out the benefits for the company and its partners, the effects on current partners, and the options that management expects the alliance to create in the future.

Too many managers approach deals with an acquisition mind-set. They should instead be open to alliances, taking to heart the evidence that big ones can really move the market. Smaller deals will also be necessary, but they can be made routine by establishing basic templates that leave senior management free to focus on the relatively few deals that really matter.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter