Publications Taxation Of Cross-Border Mergers And Acquisitions: Canada 2016

- Publications

Taxation Of Cross-Border Mergers And Acquisitions: Canada 2016

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

Introduction

Although not defined by statute, the phrase ‘mergers and acquisitions’ (M&A) is used in Canada to describe combinations of business enterprises by means of an acquisition or other combination technique, such as an amalgamation, that is allowed under applicable corporate law. A merger or acquisition involving shares of a Canadian company or its assets can be completed in a number of ways, depending on the type of consideration to be paid, tax and financing considerations, as well as corporate law and regulatory issues.

The M&A market in Canada has maintained steady, slow growth. Since the last edition of this report, tax developments relating to M&A have been limited. This report begins with an overview of recent developments in the Canadian tax environment for M&A and then addresses the principal issues that face prospective purchasers of Canadian companies and their assets.

Recent developments

Treaty shopping and base erosion and profit shifting

The Department of Finance (Canada) has announced a domestic treaty-shopping rule. The rule has not been enacted, and no draft legislation has been released. However, the rule will likely include a provision that a conduit is presumed to be abusive in the absence of support to the contrary.

In addition, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) seeks to target structures involving the use of entities formed in specific treaty countries to avoid or reduce withholding tax (WHT) or that avoid capital gains tax. Canada is a member of the OECD and will give serious consideration to any OECD initiatives. Recently, the Department of Finance commented on the OECD’s Action Plan on BEPS without providing any concrete proposals or guidance but emphasizing that preserving the competitiveness of Canada’s tax system remains a priority.

As a result, international structures are subject to greater scrutiny from tax authorities.

Stock options

If properly structured, the taxable benefit associated with employee stock options may be subject to favorable tax treatment through a deduction of 50 percent of the taxable benefit. Part of the recently elected federal government’s platform was to increase taxes on employee stock options by eliminating the deduction in respect of employee stock option benefits in excess of 100,00 Canadian dollars (CAD) annually. Details of the new stock option regime have not been announced, but the federal government has indicated that existing employee stock options would be grandfathered and the changes would only take effect once announced.

Goodwill amortization

Under current law, 75 percent of the purchase price of goodwill and certain other intangibles form part of a special tax pool for eligible capital property, which is amortizable on a declining balance basis at the rate of 7 percent annually. Recently, the Department of Finance indicated its intention to replace this regime with a new class of depreciable property for capital cost allowance purposes. Expenditures would be added to the class at a 100 percent inclusion rate, and the pool would be amortizable at the rate of 5 percent annually. Transitional rules for existing eligible capital property pools are expected; however, no draft legislation has been released.

Intercorporate dividend recharacterization rules

A vendor of shares may prefer to recognize part of the gain as an intercorporate dividend (e.g. received by a holding corporation) rather than as proceeds of disposition in order to reduce the overall rate of taxation realized by the vendor. However, anti-avoidance rules may apply to recharacterize such intercorporate dividends as proceeds of disposition giving rise to a capital gain, in general terms, to the extent the intercorporate dividend is attributable to something other than tax-paid retained earnings. The scope of these anti-avoidance recharacterization rules was significantly expanded in 2015, which will impact vendor divestiture planning and other reorganization transactions.

Foreign affiliate dumping rules

The foreign affiliate dumping (FAD) rules aim to curtail the use of Canada’s foreign affiliate (FA) system where the relevant Canadian company (referred to as a ‘CRIC’) is controlled by a non-resident corporation. Generally, the FAD rules are engaged where a CRIC makes an investment in an FA.

The term ‘investment’ is broadly defined for purposes of the FAD rules. Where a foreign-controlled CRIC makes an investment in an FA, one of the following two results generally arise:

- The paid-up capital of cross-border classes of shares is suppressed or reduced by the amount of the investment.

- The CRIC is deemed to have paid a dividend to its non-resident parent equal to the fair market value of any property transferred (excluding shares of the CRIC itself), obligation assumed or benefit conferred by the CRIC that is considered to be related to the FA investment.

Both results create WHT implications. There are a few exceptions to the FAD rules that could apply.

The FAD rules continue to have significant implications for acquisitions of Canadian corporations with significant foreign subsidiaries. The application of the FAD rules to any situation requires an in-depth understanding of the relevant specific provisions.

Thin capitalization

Canadian thin capitalization rules have been tightened in recent years. Changes include the following:

- The debt-to-equity ratio was decreased from 2:1 to 1.5:1.

- Debt owed by partnerships (with a Canadian resident member) is now considered for purposes of the thin capitalization rules.

- Disallowed excess interest expense is treated as a deemed dividend subject to WHT.

- The rules were extended to Canadian resident trusts and certain non-resident corporations and non-resident trusts that carry on business in Canada, as well as partnerships where one of the aforementioned entities is a partner.

- Back-to-back loan rules were introduced.

Corporate loss trading

In March 2013, measures were introduced to further restrict the trading of tax attributes among arm’s length persons. The ‘attribute trading restriction’ is an anti-avoidance rule that supports the existing loss restriction rules that apply on the acquisition of control of a corporation. Under the new rules, an acquisition of control is deemed to occur where a person (or group of persons), without otherwise acquiring control of the corporation, acquires shares of a corporation that have more than 75 percent of the fair market value of all the shares of the corporation, where it is reasonable to conclude that one of the main reasons for not acquiring control was to avoid any of the restrictions that would have been imposed on the corporation’s tax attributes.

At the same time, rules were introduced to extend the loss streaming and related acquisition of control rules to trusts where there is a ‘loss restriction event’. A ‘loss restriction event’ occurs when a person or partnership becomes a majority-interest beneficiary of the trust or a group of persons becomes a majority-interest group of beneficiaries of the trust.

Upstream loans

These rules generally require an income inclusion in Canada where a foreign affiliate (or a partnership of which a foreign affiliate is a member) of a Canadian taxpayer (Canco) makes a loan to a person (or partnership) that is a ‘specified debtor’ in respect of Canco, and the loan remains outstanding for more than 2 years. Recently revised coming-into-force measures provide grandfathered loans with a 5-year repayment period. The loan then becomes subject to the 2-year repayment period, so grandfathered loans generally must be repaid by 19 August 2016 to avoid being subject to the new rules.

Asset purchase or share purchase

An acquisition of a business may take many different forms. The most common way is the purchase of assets or shares. There are many significant differences in the tax implications of an acquisition of assets versus shares. The choice largely depends on the purchaser’s and vendor’s tax positions and preferences.

Typically, a vendor would prefer to sell shares, since it would expect capital gains treatment on the sale (50 percent inclusion rate for tax purposes) and may be entitled to a capital gains exemption. In contrast, a sale of assets could result in additional tax from recapture of capital cost allowances (tax depreciation) and double taxation of sale proceeds when they are extracted from the corporation.

A purchaser would typically prefer to acquire assets, since the tax cost of the assets would be stepped up to fair market value, resulting in a higher tax shield, as opposed to inheriting the historical tax shield.

The following sections discuss in more detail some of the major income tax issues that should be reviewed when considering a purchase of assets or shares. Other non-tax issues should also be considered.

In addition, the last section of this report summarizes certain advantages and disadvantages of an asset versus share purchase.

Purchase of assets

An asset purchase generally results in an increase to fair market value in the cost basis of the acquired assets for capital gains tax and depreciation purposes, although this increase is likely to be taxable to the vendor. Further, an asset purchase enables a purchaser to avoid assuming the vendor’s tax liabilities and historical attributes in respect of the assets.

Purchase price allocation

A purchase and sale agreement relating to the acquisition of business assets usually includes a specific allocation of the purchase price between the various assets acquired. To the extent that the acquisition is between arm’s length parties, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) generally accepts the purchase price allocation as set out in the purchase and sales agreement. However, where one party to the transaction does not have a vested interest in the allocation of the purchase price, the CRA may seek to adjust the allocation if it believes that it does not reflect the relative fair market values of the assets.

In the case of transfers between non-arm’s length parties, the transaction is deemed to take place at fair market value for Canadian tax purposes. In reviewing such transactions, the CRA would be concerned that the aggregate purchase price and the allocation of the price to specific assets are in accordance with the related fair market values.To avoid possible adverse reassessments, a price adjustment clause is often used in non-arm’s length transactions to ensure that any adjustment of the sale price is also reflected in an adjustment of the purchase price. Such a clause may purport to provide for retroactive adjustments to the purchase price if the CRA successfully challenges the fair market value or the related allocations.

Goodwill

For Canadian tax purposes, 75 percent of the amount paid for goodwill and other capital expenditures for similar intangible property on the acquisition of a business as a going concern is deductible on a declining-balance basis. The amortization rate is 7 percent of the unamortized balance at the end of each year. On a subsequent disposal of the goodwill, a recapture of amounts previously deducted can result. Any recapture of previously deducted amounts is fully included in income, and any amount realized in excess of the original cost is included in income at a 50 percent inclusion rate.

Recently, the Department of Finance Canada indicated its intention to replace this regime with a new class of depreciable property for capital cost allowance purposes. Expenditures would be added to the new class at a 100 percent inclusion rate, and the pool would be amortizable at the rate of 5 percent annually. Transitional rules for existing eligible capital property pools are expected; however, no draft legislation has been released.

Depreciation

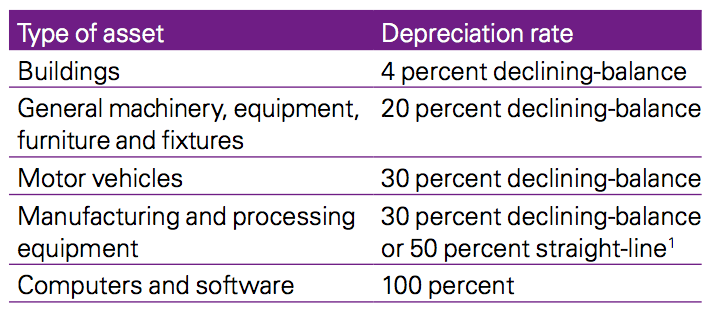

The cost of most tangible assets acquired, other than land, can be depreciated for Canadian tax purposes. Each type of property acquired must be included in a particular class of assets for capital cost allowance purposes. The rates of depreciation, which vary by class, are generally intended to be indicative of the useful lives of the assets included in the specific class. Rates for some of the more common classes of assets are as follows:

(1. The 50 percent rate applies to M&P equipment acquired before 2016. Certain requirements must be satisfied for the 30 percent rate.)

Tax depreciation is usually calculated on a declining-balance basis by multiplying the depreciation rate by the closing balance in the account (essentially, cost less accumulated depreciation and sale proceeds). The amount of depreciation that can be claimed in the year that assets are acquired is generally limited to 50 percent of the amount otherwise determined. In addition, the amount of depreciation otherwise available is prorated for a short taxation year.

On a disposal of depreciable property, any amounts previously deducted as depreciation could be recaptured and included in income when the closing balance of the account becomes negative. Additionally, any proceeds realized over the original cost are treated as a capital gain that is included in income at a 50 percent inclusion rate.

The cost of intangible assets with a limited life may also be depreciated for tax purposes. For example, the cost of licenses, franchises and concessions may be depreciated over the life of the asset. Patents or a right to use patented information for a limited or unlimited period may be depreciated on a 25 percent declining-balance basis. Alternatively, limited life patents can be depreciated over the life of the asset. Premiums paid to acquire leases or the cost of leasehold improvements are generally deducted over the life of the lease.

Tax attributes

On a sale of assets, any existing losses remain with the corporate vendor and generally may be used by the vendor to offset capital gains or income realized on the asset sale. Likewise, a vendor’s depreciation pools are not transferred to the purchaser on an asset acquisition.

Indirect taxes (value added tax and provincial sales tax)

Canada has a federal valued added tax (VAT) known as the goods and services tax (GST). GST is a 5 percent tax levied on the supply of most goods and services in Canada. Five participating provinces (Ontario, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Newfoundland) have harmonized their provincial sales taxes (PST) with GST to create the harmonized sales tax (HST). HST generally applies to the same base of goods and services as GST, but at rates of between 13 and 15 percent for supplies made in the harmonized provinces (the rate depends on the province in which the supply is made). Quebec also has a VAT, called Quebec Sales Tax (QST), which is similar but not identical to the GST and HST. The QST rate is 9.975 percent. Three provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan) impose PST on goods and certain services at the rate of between 5 and 8 percent.

The sale of business assets by a registered person constitutes a supply of goods for GST/HST purposes and, as a general rule, the tax would have to be collected. However, where a registered person makes a supply of a business or part of a business and the recipient is a GST/HST registrant and is acquiring all or substantially all of the property that can reasonably be regarded as being necessary to carry on the business or part of the business, no GST/HST is charged on the purchase price, provided a joint election is made. As long as the assets sold are part of a going concern of the vendor that will continue to be carried on commercially by the purchaser, this relieving provision should apply. Where the relieving provision does not apply, the tax is charged based on the consideration for the assets sold. However, not all assets are subject to GST/ HST (e.g. sale of accounts receivable) and special rules apply to real property and to related-party transactions.

Where GST/HST does apply, the purchaser should be able to recover the tax paid to the vendor through a refund mechanism called an ‘input tax credit’, provided the purchaser is registered for GST/HST at the time the assets are deemed to have been supplied and the purchaser is using the assets in its commercial activities.

The sale of tangible assets located in a PST province may be subject to PST depending on the type and/or use of the tangible asset. Other PST-related obligations may apply on the transfer of tangible assets (such as clearance certificates). Generally, PST is a non-recoverable tax.

Transfer taxes

Most of the provinces impose land transfer taxes on transfers of real property: land, buildings and other improvements. The rates of land transfer tax vary by province and range from 0.25 to 2 percent of the consideration for the real property transferred. Certain exemptions from land transfer taxes apply to non-arm’s length transactions (non-arm’s length exemption). No stamp or transfer duties are generally payable on the transfer of shares. Some of the provinces may impose land transfer tax if a transfer of shares occurs within a certain period after the transfer of real property that was eligible for a non-arm’s length exemption.

Purchase of shares

The following sections discuss some issues that should be considered when acquiring a target company’s shares.

Tax indemnities and warranties

A purchaser of a target company’s shares assumes the historic tax liabilities of target.Therefore, the purchase and sale agreement for the share usually contains representations and warranties regarding the tax status of the target company, the breach of which gives rise to indemnification by the vendor. Whether the indemnity is subject to any cap or basket usually forms part of the business negotiation. Given the historic tax liabilities that may carry over to the purchaser on a sale of shares, it is customary for the purchaser to initiate a tax due diligence process that would incorporate a review of the target’s tax affairs, notwithstanding that the vendor may provide indemnities and warranties.

In a public company takeover, the target company may allow the purchaser a suitable due diligence period and make available to the purchaser most financial and corporate information. Typically, this due diligence process would include an in-depth review of the tax affairs of the target company by the advisors of the purchaser.

In a hostile takeover of a public company, a due diligence review normally would not be carried out.

Ability to step-up tax cost

On an acquisition of assets, the total purchase price is allocated to the specific assets acquired, based on their respective fair market value, as negotiated by the parties. Depending on the allocation, a step-up in the tax basis of the acquired assets is available. On an acquisition of shares, there is generally no increase in the tax basis of the assets of the target company and no goodwill is recognized for tax purposes.

The tax basis of certain non-depreciable capital properties owned by the target company can be increased if the target company is amalgamated with or wound up into the Canadian acquisition company. This is often referred to as a ‘bump’. Properties eligible for the bump include shares of subsidiaries of the target company, partnership interests (to the extent of accrued gains on underlying capital property) and land.

The bump cannot exceed the fair market value of the eligible property at the time the target company was acquired.The total bump is limited to the excess of the purchase price of the shares of the target company over the net tax cost of the assets of the target company. Additionally, the bump room on shares of foreign affiliates is subject to specific limitations based on the tax-free surplus balances of the foreign affiliates. Accordingly, taxpayers need to calculate the surplus balances of foreign affiliates of the Canadian target entity and make appropriate tax elections to utilize the surplus balances to reduce the proceeds received. Under an administrative position, the CRA will not challenge surplus calculations (or the lack thereof) of foreign affiliates that are moved out from under Canada within a reasonable time if certain other conditions are met. Accordingly, in certain cases, it may not be necessary to conduct surplus calculations.

The bump rules are extremely complex, and careful planning is required to ensure the bump will be available. In certain cases, obtaining a bump is a critical aspect of the transaction. For example, the target company may operate three lines of business through three subsidiaries. If the non-resident acquirer only desires to acquire and operate two of the businesses, a bump may be desirable to minimize the taxes on the sale of the non-desired assets.

Typically, to structure a bump, a Canadian acquisition company could acquire the target company, after which the target would be wound up into or merged with the Canadian acquisition company. The tax basis of the shares of the subsidiary operating the unwanted business could be bumped to their fair market value (subject to the restrictions described earlier) and sold to a third party without income tax consequences (if the bump is available).

When a bump is to be obtained on the tax basis of the assets of the target, the purchaser may request representations or covenants from the vendor that it has not and will not enter transactions that could adversely affect the bump.

Tax losses

A Canadian company may carry forward two primary types of losses: net capital losses and non-capital (or business) losses. Capital losses are incurred on the disposal of capital property. Half of such losses must be deducted against the taxable portion of capital gains (50 percent) realized in the year, with any excess loss being available for carry forward or back as a net capital loss. Net capital losses may be carried back 3 years or forward indefinitely, but they may only be used to reduce taxable capital gains in these periods. Non-capital losses (NOL) are generally business or property losses that may be carried back 3 years or forward 20 years and generally applied against income from any source.

On a sale of assets, any existing losses remain with the corporate vendor, which can generally use them to offset any capital gains or income realized on the asset sale.

On a share sale that results in an acquisition of control of the target corporation, a deemed tax year-end is triggered immediately before the acquisition. A number of specific rules determine the carry forward and use of pre-acquisition losses, as discussed below. Generally, accrued capital losses on capital assets of the corporation are deemed realized, which results in a write-down of capital property to its fair market value. Net capital losses may not be carried forward after an acquisition of control, so planning should be undertaken to utilize such losses if possible.

On an acquisition of control, accrued terminal losses on depreciable properties are deemed realized and bad debts must be written-off. These deductions from income in the taxation period that ends at the time of the acquisition of control may increase the target corporation’s non-capital losses. Non-capital losses are only deductible following an acquisition of control within the carry forward period if certain requirements are met. Non-capital losses from carrying on a business may be deductible after the acquisition of control if the business that sustained the losses continues to be carried on with a reasonable expectation of profit. However, such losses are deductible only to the extent of the corporation’s income from the loss business or similar businesses. Similarly, on a liquidation of an acquired company or the amalgamation of the acquired company with its parent, the pre-acquisition non-capital losses are deductible by the parent but only against income from the business of the acquired corporation in which the losses arose or from a similar business.

Non-capital losses that do not arise from carrying on a business (referred to as ‘property losses’) cannot be used after an acquisition of control. Thus, planning should be undertaken to utilize such losses if possible.

Despite the above-noted rules, the target company may elect to trigger accrued gains on depreciable and non-depreciable capital property to offset any net capital or non-capital losses either carried forward or deemed realized on the acquisition of control that would otherwise expire. The general effect of these rules is to allow a corporation, before the change of control, to convert net capital losses or non-capital losses existing or accrued at that time into a higher cost base for capital assets that have current values that exceed their tax basis.

Pre-sale dividend

In certain cases, the vendor may prefer to realize part of the value of their investment as income by means of a pre-sale dividend and hence reduce the proceeds of sale. This planning may be subject to the section 55 anti-avoidance rules. If the rules apply, the dividend is deemed to be proceeds of disposal and thus give rise to a capital gain rather than a dividend. However, if the dividend can be attributed to ‘safe income on hand’ (generally, retained earnings already subjected to tax), these anti-avoidance rules should not apply. The scope of these anti-avoidance rules has been significantly expanded in recent years.

Transfer taxes

No stamp or indirect taxes are payable on a transfer of shares.

However, for an asset sale, most provinces impose land transfer taxes on transfers of real property (e.g. land, buildings, improvements), and sales taxes (e.g., PST, GST, HST) may apply.

Tax clearances

The CRA does not give clearance certificates confirming whether a potential target company has any arrears of tax owing or is involved in any audit or dispute relating to prior audits. It is recommended that comprehensive tax due diligence be performed on a Canadian target corporation.

Clearance from the tax authorities is not required for a merger or acquisition except in certain circumstances where the vendor is a non-resident. Where a non-resident disposes of taxable Canadian property, the vendor may have obligations under section 116 of the Income Tax Act.

Taxable Canadian property includes:

- Canadian real property

- assets used in carrying on business in Canada

- Canadian private company shares that derive more than 50 percent of their value from certain Canadian property

- shares of Canadian public companies where certain ownership thresholds are satisfied and which primarily derive their value from taxable Canadian property.

Unless the disposed taxable Canadian property is a ‘treaty-protected property’ and the purchaser provides the requisite notice to the CRA, a purchaser is required to remit funds to the CRA equal to a portion of the purchase price (25 or 50 percent), unless the non-resident vendor provides an appropriate clearance certificate. As the purchaser is entitled to withhold from the purchase price in order to fund its remittance obligation, it is important to deal with these issues in the legal documentation.

In addition to any clearance certificate compliance obligations, a non-resident vendor is also required to file a Canadian tax return reporting the disposition (subject to certain exceptions for treaty-exempt property).

Choice of acquisition vehicle

Several potential acquisition vehicles are available to a foreign purchaser. Tax factors often influence the choice. The following vehicles may be used to acquire either the shares or assets of a Canadian target company.

Local holding company

The use of a Canadian acquisition company to acquire either assets or shares of a Canadian target company is common.

A Canadian acquisition company is often used when a non-resident acquires shares of a Canadian target corporation. On a share acquisition, the use of a Canadian acquisition company may be advantageous for financing the acquisition or for deferring Canadian WHT on distributions in the form of a return of paid-up capital (as discussed below). In addition, a deferral of WHT can be achieved where there are minority Canadian shareholders of the acquired company (e.g. employees, public shareholders) and dividends are paid on a regular basis. The foreign parent may not require its share of the dividends to be repatriated and can defer Canadian WHT by using a Canadian holding company.

A return of paid-up capital (generally, the amount for which the shares were originally issued to the original holder) is not subject to income tax or WHT. Therefore, if a non-resident acquires a Canadian target company directly, the amount paid to acquire the shares of the target company can only be returned to the non-resident free of WHT to the extent of any existing paid-up capital. If the non-resident incorporates a Canadian acquisition company, the tax basis and paid-up capital of the shares of the acquisition company should both be equal to the purchase price (assuming no debt financing). The paid-up capital of the acquisition company can be repatriated to the non-resident parent free of Canadian WHT.

After the share purchase, the Canadian acquisition company and the target company may be amalgamated (i.e. merged; see discussion under company law). An amalgamation of the two entities will be useful for debt financing (to ‘push down’ the interest expense against the operating assets), since Canada does not have tax-consolidation.

An amalgamation of the acquisition and target companies results in deemed year-ends immediately before the amalgamation for both companies. As discussed later in this report, a deemed year-end also occurs when control of a company is acquired. To potentially avoid extra year-ends, the amalgamation could be effected on the same day as the share acquisition so the deemed year-ends coincide (depending on all relevant transactions).

Foreign parent company

The foreign parent company may choose to make the acquisition directly, perhaps to shelter its own taxable profits with the financing costs (at the parent level), but there are two main disadvantages to this approach:

- The parent inherits the historical paid-up capital instead of having a paid-up capital equal to the purchase price. In some cases, historical paid-up capital could exceed the purchase price, for example, where the target corporation has declined in value.

- It would be more difficult to push debt into Canada or leverage Canada.

As discussed earlier in this report, paid-up capital is advantageous from a Canadian tax perspective when a distribution is made through a return of capital, since it does not attract Canadian WHT. Therefore, an intermediary holding company resident in a favorable treaty country is preferable to a foreign parent company from a Canadian tax perspective.

Non-resident intermediate holding company

A treaty country intermediary shareholder may be advantageous in certain cases, depending on the jurisdiction of incorporation of the non-resident purchaser. Canada has an extensive tax treaty network. The treaty WHT rates vary from 5 to 25 percent on dividends and from 0 to 15 percent on interest (see this report’s discussion on WHT on debt.) The domestic Canadian withholding rate is 25 percent for non-treaty countries.

Some treaties provide greater protection against Canadian capital gains tax on the disposal of shares of a Canadian company than the normal Canadian taxation rules that apply to disposals by non-residents. As a result, the use of a treaty country intermediary to make the acquisition may be useful in certain circumstances. As with all international tax planning, it is necessary to consider treaty-shopping provisions in the treaties, substance requirements and domestic anti-avoidance rules.

Local branch

The use of a branch to acquire assets of a target company yields similar results to forming a Canadian company, assuming the acquisition creates a permanent establishment in Canada. The rate of federal and provincial income tax is approximately the same for a branch as for a Canadian corporation. In addition, a branch tax generally is imposed on profits derived by non-resident corporations from carrying on business in Canada and not reinvested in Canada. The branch tax parallels the dividend WHT that would be paid if the Canadian business were carried on in a Canadian corporation and profits were repatriated by paying dividends to its non-resident parent. Accordingly, the branch tax base is generally intended to approximate the after-tax Canadian earnings that are not reinvested in the Canadian business.

However, in the case of a Canadian subsidiary, the timing of distributions subject to WHT can be controlled, but branch tax is exigible on an annual basis. Some of Canada’s tax treaties provide an exemption from branch tax on a fixed amount of accumulated income (e.g. CAD 500,000).

In certain cases, it is advantageous for a non-resident corporation starting a business in Canada initially to carry on business as a branch, because of the ability to use start-up losses against the non-resident parent’s domestic income or the availability of a partial treaty exemption from branch tax. Subsequently, the branch can be incorporated and a tax rollover may be available.

Joint venture

Where an acquisition is made in conjunction with another foreign or domestic party, a special-purpose vehicle, such as a partnership or joint venture, may be considered. However, the use of such a vehicle still requires fundamental decisions as to whether the participant in the partnership or joint venture should be a branch of the foreign corporation or a Canadian subsidiary and whether a treaty country intermediary should be used.

Incorporation offers the advantages of limited liability by virtue of a separate legal existence of the corporate entity from its members. A limited partnership may offer similar protection, but a limited partner cannot participate in the management of the partnership. A general partnership results in the joint and several liability of each partner for all of the partnership liabilities, although limited liability protection can be offered by using a single-purpose domestic corporation to act as partner.

The primary advantage of using joint ventures or partnerships to make acquisitions with other parties is that losses realized by a joint venture or a partnership are included in the taxable income calculation of the joint venturers or partners. In contrast, corporate tax-consolidation is not permitted for Canadian tax purposes, so losses incurred by a corporate entity must be used by that entity and generally can only be transferred to another Canadian company in the group on liquidation, amalgamation or, potentially, through a complex loss-utilization transaction.

Choice of acquisition funding

A purchaser using a Canadian acquisition vehicle to carry out an acquisition for cash needs to decide whether to fund the vehicle with debt, equity or a hybrid instrument that combines the characteristics of both. The principles underlying these approaches are discussed below.

Debt

The principal advantage of acquiring shares of a corporation through debt financing is the potential tax-deductibility of interest (and other related financing fees). The combined federal and provincial corporate tax rates in Canada may be higher than in some other countries. As a result, it may be desirable to have financing costs relating to Canadian acquisitions deductible in Canada against income that would otherwise be taxable at the Canadian rates and subject to Canadian WHT on repatriation. Since there is no tax-consolidation, it is important that any financing costs be incurred by the entity that is generating income.

The Canadian rules relating to interest deductibility generally permit a purchaser to obtain a deduction for interest expense on acquisition debt. Interest on money borrowed by a Canadian acquisition company to acquire the shares of a target company is generally fully deductible. However, the acquisition company may not have sufficient income against which the interest expense can be deducted, which could result in unused interest deductions. To the extent that the target company is subsequently liquidated into or amalgamated with the acquisition company, the interest on the acquisition debt should be deductible against the profits generated by the business of the target company.

The main restriction on acquisition debt funding obtained from a non-resident related party is in the thin capitalization rules. Interest on the portion of debt owed by a Canadian corporation (target company) to certain non-residents that exceeds 1.5 times the shareholder’s equity of the Canadian target company is not deductible. The interest that relates to the portion of the debt below the 1.5:1 debt-to-equity threshold is generally deductible. Interest that relates to the portion of the debt above the 1.5:1 debt-to-equity threshold is treated as a deemed dividend subject to WHT.

The thin capitalization rules apply if the shareholder is a specified shareholder, which includes non-resident shareholders and other related parties who together own at least 25 percent of the voting shares or 25 percent of the fair market value of all the shares in the company.

Deductibility of interest

Canada has rigid interest deductibility rules — interest expense is not automatically deductible. Interest is deductible for Canadian tax purposes if it is paid pursuant to a legal obligation to pay interest and relates to:

- borrowed money used to earn income, or

- an amount payable for property acquired for the purpose of earning income.

In computing business income, accrued interest is generally fully deductible for tax purposes, although compound interest is only deductible when paid. Some financing fees are generally deductible over 5 years for tax purposes while others must be capitalized and amortized at a rate of 7 percent per year on a declining basis.

Where shares of a company are redeemed for a value in excess of paid-up capital and retained earnings, or dividends are paid in excess of retained earnings, interest expense incurred to fund such redemptions or dividends may not be tax-deductible.

Interest-free loans made between Canadian corporations generally do not give rise to any adverse tax consequences. Similarly, interest-free loans made by a non-resident shareholder to a Canadian company generally do not give rise to adverse Canadian tax consequences. However, in the case of interest-free loans made by a Canadian company to a related non-resident that remain outstanding for more than 1 year, interest income will be imputed to the Canadian company, subject to certain exceptions. Further, such a loan to a non-resident shareholder is treated as a dividend to the non-resident shareholder and subject to WHT if outstanding for more than 1 full taxation year. The non-resident shareholder may be permitted to claim a refund of the WHT paid when the interest-free loan is repaid, provided the repayment is not part of a series of loans or other transactions and repayments.

Withholding tax on debt and methods to reduce or eliminate it

Interest paid by a Canadian resident corporation to a non-arm’s length non-resident lender is subject to WHT. The domestic rate of withholding is 25 percent. However, the rate is generally reduced under Canada’s tax treaties to 10 or 15 percent. Under the Canada-US tax treaty, the rate could be reduced to 0 percent if the recipient qualifies for treaty benefits.

WHT does not apply to non-participating interest paid to an arm’s length, non-resident lender. WHT also generally does not apply where the non-resident lender receives the interest in connection with a fixed place of business in Canada, in which case the lender would be subject to normal Canadian income tax.

Because Canadian WHT applies only at the time of payment or crediting, WHT can be deferred to the extent that interest is not actually paid or credited. However, interest that is accrued by a Canadian-resident taxpayer and owed to a non-arm’s length, non-resident is not deductible by the Canadian-resident corporation if payment is not made within 2 years from the end of the taxation year in which the interest accrued.

Checklist for debt funding

- The use of bank debt may be advantageous for several reasons: no thin capitalization rules, no transfer pricing problems on the interest rate, and no WHT on interest payments.

- If the debt is funded from a related party, consider whether the 1.5:1 debt-to equity thin capitalization restrictions apply. WHT may apply on the interest paid.

- Consider whether the level of profits will enable tax relief for interest payments to be effective.

- Consider whether interest-free loans would have interest imputed if loans from a Canadian corporation to a non-resident are outstanding for more than 1 year.

- Consider whether a deemed dividend exists when loans from a Canadian corporation to a non-resident remain outstanding for more than a year.

- Consider whether there is an income inclusion to the Canadian corporation on upstream loans made by its foreign affiliates.

- If the debt borrowed by the Canadian target company to redeem shares exceeds paid-up capital and retained earnings or dividends are paid in excess of retained earnings, interest expense incurred to fund the excess amounts relating to such distributions may not be tax-deductible.

- Consider whether transfer pricing principles could apply to interest rates charged on related-party debts.

- Consider whether there are cash flow issues and whether interest payments made on related party debt may be deferred for 2 years.

Equity

A purchaser may use equity to fund its acquisition. The amount of equity depends on the purchaser’s preference. Canada does not have any stamp duties.

Dividends paid by a Canadian company to a corporate shareholder resident in Canada generally are not subject to income tax for the recipient or WHT for the payer, although a refundable tax applies to private companies receiving dividends on portfolio investments. Special rules may apply to dividends paid on preferred shares, in which case there is a form of advance corporation tax (discussed later). Payments of dividends are not deductible by the payer for income tax purposes.

Canadian tax rules permit deferred transfers and amalgamations where certain conditions are met. Some commonly used tax-deferred reorganizations and mergers provisions are as follows:

- A transfer of assets to a corporation results in a taxable disposition of the assets at fair market value. However, if the transferor and transferee make a joint election, potentially all or a portion of a gain on the transfer of eligible assets can be deferred. This election permits a tax-deferred transfer or rollover of property to a taxable Canadian corporation as long as the transferor receives shares as part of the consideration for the transfer. The adjusted cost base of the shares they receive should equal the adjusted cost base of the assets transferred (assuming no non-share consideration is received). The deferred income or capital gain arises only when the shares are sold in an arm’s length transaction. However, double taxation is inherent in the rollover since the transferee corporation also inherits the adjusted base of the assets received as its adjusted base of those assets.

- A similar election is available for a transfer of assets to a partnership.

- A rollover is also available for a shareholder of a corporation who exchanges:

— shares of a corporation for shares of the corporation or exercises a conversion right to convert debt into shares of a corporation (no election required)

— shares of one taxable Canadian corporation for shares of another taxable Canadian corporation (no election required); this provision is most often used in a takeover where arm’s length shareholders of one corporation exchanges shares for shares of the purchasing corporation.

The section of the Income Tax Act governing the rollover prescribes, among other things, the type of property eligible for transfer, whether the transferor can receive anything other than shares in return and whether an election is required.

In the event of an amalgamation (merger) of two Canadian taxable corporations, a tax-deferred rollover may be available in which no immediate tax implications should arise for the corporations and their shareholders, provided certain conditions are met. If all the conditions are met, the rollover provision should apply automatically without an election.

While the amalgamation generally should rollover the principal tax attributes of the predecessor corporations to the amalgamated entity, each predecessor corporation will experience a deemed year-end immediately before the amalgamation. The deemed year-end will age by 1 year any loss carry forwards. Other provisions related to the timing of a year-end should be considered, including the proration of amounts in a short taxation year. This tax-deferred rollover generally allows the corporations and shareholder to be in a tax-neutral position.

If the merger is a vertical amalgamation (between a parent and its wholly owned subsidiary), two additional planning opportunities may be available: utilization of post-amalgamation losses to recover taxes paid by the predecessor parent and access to the ‘bump’ (as discussed earlier), subject to certain conditions.

A tax-deferred wind-up is also available if certain conditions are met (i.e. the subsidiary must be a taxable Canadian corporation of which at least 90 percent of each class of shares is owned by another Canadian taxable corporation). This tax-deferred wind-up is similar to the tax-deferred amalgamation except there is no deemed year-end.

Hybrids

The Canadian tax treatment of a financial security, either as a share or as a debt obligation, is largely determined by the legal form of the security as established by the applicable corporate law. A dividend payment on a share is generally treated as a dividend regardless of the nature of the share (i.e. common or preferred). An interest payment on a debt obligation is generally considered to be interest for tax purposes, although its tax-deductibility may be limited.

The Canadian tax authorities generally characterize a financial security issued by a foreign corporation as either debt or equity in accordance with the corporate law of the jurisdiction in which the security is issued, having regard to Canadian commercial law principles. The tax treatment of the security in the foreign jurisdiction, however, is irrelevant when it is inconsistent with the characterization under the relevant Canadian corporate law.

Discounted securities

If a company has issued a debt security at a discount and pays an amount in satisfaction of the debt security that exceeds proceeds received by the company on the issuance of security, the company may deduct all or a specified portion of the excess in certain circumstances.

Deferred settlement

To the extent that all or a portion of the purchase price is represented by debt that is not due to the vendor until after the end of the year, a reserve may be available to defer a portion of the gain that is taxable to the vendor. For disposals of shares, the reserve is limited to 5 years. At least one-fifth of the gain must be included in the vendor’s income in each year of disposal and the immediately following 4 years. For capital gains arising from a sale of assets, the same type of reserve is available to the extent that a portion of the consideration relating to capital property is not due to the vendor until after the end of the year. This reserve is not available for recaptured depreciation. For non-capital property, a 3-year reserve on the portion of the profit from the sale relating to proceeds not yet payable may be available. No reserve is available on the sale of goodwill. Reserves on certain disposals of property among related parties could be denied.

Other considerations

Concerns of the seller

Sale of assets

In an asset sale, a main concern of the vendor is the possible recapture of depreciation if depreciable assets are sold for more than their tax values. As discussed earlier, only 50 percent of the gain on goodwill and other non-depreciable capital properties may be included in income. (However, a company may have previously amortized purchased goodwill or intangibles, in which case recapture would arise.) Therefore, the vendor will be concerned with the relative allocation of the purchase price to minimize the recovery of depreciation compared with the gains from capital property or goodwill.

PST and GST/HST are generally collectible by the vendor from the purchaser on an asset sale. To the extent these taxes are not collected (in the absence of an appropriate exemption), the vendor is liable for such taxes plus interest. Land transfer tax is also payable by the purchaser to the appropriate government authority.

Sale of shares

A Canadian-resident vendor is taxable on 50 percent of any capital gains realized on a sale of shares. An exemption may be available to individuals for a portion of the gains realized on shares of qualifying private corporations. Prior to a share sale, shareholders owning more than 10 percent of the outstanding shares of a private company may undertake planning steps to crystallize the accumulated earnings of the target company through the payment of tax-free intercorporate dividends to a holding company. Such planning aims to increase the adjusted cost base of the vendor’s shares, thereby reducing the vendor’s capital gain arising on the sale.

Other concerns primarily relate to the negotiating process. The vendor will want to ensure that all intangible and contingent assets are recognized and taken into account in arriving at the purchase price, including any losses or other attributes in the company that may be used by the purchaser. Similarly, any tax indemnities and warranties (as discussed earlier) are a significant part of the negotiation process.

Taxable versus deferred sale

In the case of both an asset sale and a share sale, the vendor will be concerned about whether to structure the transaction primarily as a taxable or tax-deferred disposal. Generally, in order for the sale to be tax-deferred, the vendor must receive shares of the acquisition vehicle. In both an asset and a share sale, the vendor can defer recognition of gains by receiving cash or debt (‘boot’) up to the tax basis of the assets or shares disposed and shares of the purchaser for the balance of the purchase price. These transactions may be structured in a variety of ways.

Vendor’s preference regarding assets versus shares

Since a purchaser prefers an asset deal, a vendor may require a higher purchase price to sell assets rather than shares, due to the potentially higher tax cost on the sale of assets. The purchaser may pay more for assets but should obtain some tax relief through higher depreciation and amortization.

Company law and accounting

Although not defined by statute, the term ‘M&A’ is used in Canada to describe combinations of business enterprises by means of an acquisition or other combination techniques, such as amalgamation, that are allowed under company law. A merger or acquisition involving shares of a Canadian company or its assets can be completed in a number of ways depending on the type of consideration to be paid (generally cash, shares, or other securities), tax and financing considerations, and company law and regulatory issues.

The applicable company law that governs a Canadian corporation depends on the jurisdiction of incorporation. A corporation can be incorporated under either the federal Canada Business Corporations Act (CBCA) or one of the provincial corporation statutes.

Canadian federal and provincial company laws provide for the statutory amalgamation of two or more predecessor companies into a single entity, provided each is governed by the same corporate statute. Thus, to amalgamate a corporation incorporated under provincial company law with another corporation incorporated under different provincial company law (or under federal company law), one corporation must be continued from its original jurisdiction into the other corporate jurisdiction (if allowed under its governing company law). Under Canadian company law, an amalgamated corporation essentially represents a continuation of each predecessor corporation, including all of their property rights and liabilities (neither predecessor is considered as a ‘survivor’ of the other).

Company law generally does not require that each shareholder of a predecessor corporation becomes a shareholder of the amalgamated corporation. Thus, it is possible to structure a triangular amalgamation whereby shares of the parent company of one predecessor corporation are issued to shareholders of the other predecessor corporation on amalgamation.

Canadian accounting standards for business combinations generally align with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and require the acquisition of a business to be accounted for using business combination accounting, unless the acquisition represents a transaction between companies under common control. The net assets acquired are brought onto the consolidated balance sheet at their fair values, and goodwill arises to the extent that the consideration given exceeds the aggregate of these values. Goodwill is not amortized through the profit or loss account; it is subject to a mandatory annual impairment test. Business combination accounting also applies to purchases of assets, provided such assets constitute a business. Acquisitions of assets not constituting a business do not give rise to goodwill.

Group relief/consolidation

There is no tax-consolidation in Canada. Within a corporate group, it is advantageous to ensure that a situation does not arise where losses are incurred in one company and profits in another. It is possible to effect tax-deferred mergers of companies through liquidations of wholly owned subsidiaries or amalgamations of related companies whereby assets can be transferred at their tax basis and accumulated losses can be transferred to the parent on liquidation or to the amalgamated company. In addition, more complex loss-utilization structures can be implemented within a corporate group.

As discussed earlier, where a Canadian operating company is acquired by a Canadian acquisition company, it may be necessary to merge the acquiring and operating companies so that the interest on any acquisition debt is deductible against the profits of the operating company.

Transfer pricing

Canadian transfer pricing rules require a taxpayer transacting with a non-arm’s length non-resident to use arm’s length transfer prices and terms, and comply with certain contemporaneous documentation requirements. Failure to use arm’s length transfer prices may result in a transfer pricing adjustment and penalties, including penalties for insufficient contemporaneous documentation.

After the acquisition, intercompany balances and arrangements between a foreign parent and its Canadian subsidiary that do not reflect arm’s length terms may be subject to adjustment or re-characterization under Canada’s transfer pricing rules.

Dual residency

All corporations governed by Canadian corporate statutes are deemed to be residents of Canada for tax purposes.There is little advantage in seeking to establish a Canadian company as a dual resident company.

Foreign investments of a local target company

Canada has comprehensive rules that impute income to a Canadian-resident shareholder in respect of foreign affiliates of the shareholder that earn investment income or income from a business other than an active business. As a result, a Canadian company is generally not the most efficient entity through which to hold international investments, unless the Canadian entities operate active businesses.

Comparison of asset and share purchases

Advantages of asset purchases

- A step-up in the tax basis of assets for capital gains purposes and depreciation purposes is obtained.

- A portion of the purchase price can be depreciated or amortized for tax purposes.

- A deduction is gained for inventory purchased at higher than book value.

- It can be contractually determined which liabilities the purchaser will assume.

- Possible to acquire only part of a business.

- Flexibility in financing options.

- Profitable operations can be absorbed by loss companies in the acquirer’s group, provided certain planning is undertaken, gaining the ability to use the losses.

Disadvantages of asset purchases

- Possible need to renegotiate supply, employment and technology agreements.

- An asset sale may be less attractive to the vendor, thereby increasing the purchase price.

- Transfer taxes on real property, GST/HST and PST on assets may be payable.

- Benefit of any losses incurred by the target company or any other tax attributes remains with vendor.

Advantages of share purchases

- Usually more attractive to the vendor, so the price may be lower.

- Purchaser may benefit from tax losses and other tax attributes of the target company.

- Purchaser may gain the benefit of existing supply and technology contracts.

- Purchaser does not have to pay transfer taxes on shares acquired.

Disdvantages of share purchases

- Purchaser acquires unrealized tax liability for depreciation recovery on the difference between original cost and tax book value of assets.

- Purchaser is liable for all contingent and actual liabilities of the target company.

- No deduction for the excess of purchase price over tax value of assets.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter