Publications Sales Process Management: The Early Bird Advantage

- Publications

Sales Process Management: The Early Bird Advantage

- Bea

SHARE:

By Neil Dhar, Mark Ross – PricewaterhouseCoopers

Remember how unpleasant it was the last time you did business with an unprepared seller? Their team was long on data, but short on analysis, with a data room organized to appeal more to lawyers than businessmen. To make matters worse, the seller could not keep up with information requests. And access to management was limited, so you couldn’t get the answers you needed or cut through the red tape.

Although the buying process was painful, costly and time-consuming, you were able to use gaps in the seller’s information to gain exclusivity, demand post-close adjustments and ultimately acquire the business for a very attractive price.

It’s been some time since you bought that company and you’re getting ready to sell some of its non-essential operations or perhaps the entire unit. But deep down inside, you realize that your own divestiture process is no better than what you typically encounter when making acquisitions. And unless you fix it, there’s a very good chance that a savvy buyer will triumph the next time you put a business up for sale.

To win on the exit as well as the acquisition and avoid mistakes and omissions that diminish the value of sell side deals, you’ll need to become a prepared seller with a more disciplined framework and the necessary resources for preparing and presenting businesses for sale. This is especially true when a sophisticated buyer such as another private equity firm, hedge fund or industry leader is sitting on the other side of the negotiating table.

Breaking up is harder to do

With a white-hot M&A market, record cash levels and high multiples, it’s easy to overlook the fact that divestitures will become more complex in years to come. The sheer size and number of participants in recent club deals, as well as joint ventures between private equity and corporate buyers may lend themselves to a broader range of divestiture options going forward. While the exit of choice may still be the sale of an entire business to a corporate buyer willing to pay the full fair market price, in a growing number of instances multiple carve-outs at different points in the ownership cycle may be necessary or yield better returns, albeit at greater risk.

For example, a private equity firm buying a large manufacturer of industrial products might decide to quickly unload underperforming or redundant properties, especially if the commercial real estate market is strong. The remaining operations could then be restructured and sold, or taken public as a single entity.

Or a more complex strategy might be pursued, such as merging the newly acquired unit with one of the firm’s manufacturing platforms, or realigning/consolidating all of the firm’s manufacturing operations and selling them as more than one company. In some instances, the divestiture strategy of choice could even be an alliance with a potential corporate buyer who might bring complementary skill sets to the venture, such as improved logistics or supply chain management.

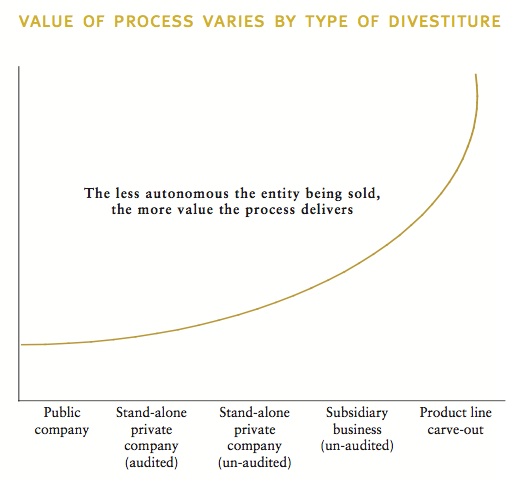

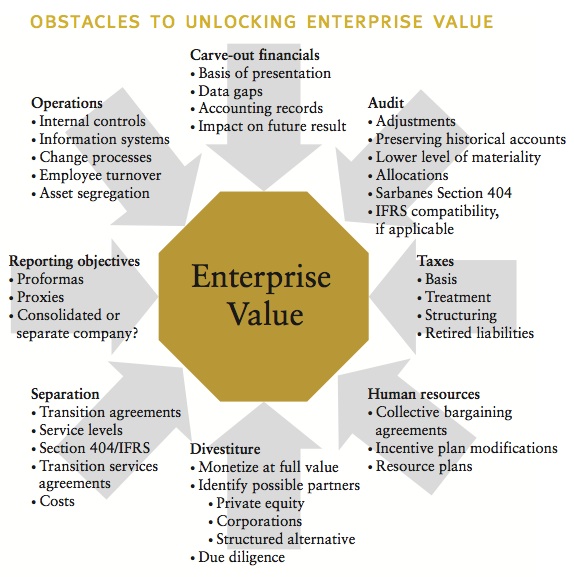

Each of these alternatives raises difficult separation, accounting and structuring issues. Getting the information you need to evaluate your options early, make swift but informed strategic decisions, and present the business in a manner that highlights its value requires a well-structured, well-resourced divestiture process. This process analyzes the business from a buyer’s perspective with a focus on careful preparation, dedicated project management and speed. It also should have the capacity and flexibility to analyze alternative divestiture scenarios from several perspectives at an early stage, and address a broad range of accounting, tax, transition, benefits, compensation and risk management issues in sufficient depth.

Designing a better process

1. Strategic considerations

The best processes begin with strategic decisions on which businesses to divest and when. For purposes of discussion, the term “businesses” is not limited to intact portfolio companies, but also includes divisions of these companies, product lines, or even baskets of assets drawn from multiple companies.

Many firms employ a systematic, ongoing, portfolio review process to identify appropriate divestiture candidates based on financial, operating and commercial parameters such as (i) a business is maturing or becoming ripe for sale because of restructuring or market factors, (ii) a business requires an infusion of capital or specialized knowledge that lies beyond the capacity of portfolio company or firm management, or (iii) the business is part of a larger acquisition and does not fit with the strategic plan of the firm or its platform companies.

Once a tentative decision is made to exit a business, the process begins with validating the case for separation and launching the planning process. This may entail obtaining preliminary answers to questions such as:

• What’s the best type of exit for my investors, and is it realistic?

• Which buyers in which markets are most likely to be willing and able to pay full price, and what are their needs and issues likely to be?

• Would a strategic partner add value, and which candidates are best fits for the business to be divested?

• What scope of diligence on prospective buyers or partners is needed from both a financial and commercial perspective?

• Which deal structures strike the best balance between buyer and seller needs?

2. Financial preparation and presentation

Since you’ll need financial information to finalize your divestiture strategy, preparation should begin as soon as you’ve identified some strategic options. The goal from the outset is presenting financial information in a manner that accurately reflects the value of the business to a potential buyer. Even when you’re selling a stand-alone business with audited financial statements, it is necessary to review and adjust the historical presentation of financial information to reflect the post-sale economics of the business. This entails validating the quality of earnings and normalizing them to eliminate charges the buyer will not incur. These include management fees your firm has charged to the business, and non-recurring expenses such as restructuring provisions or legal settlements that will not affect the business going forward.

At this stage, it is also critical to assess tax consequences the proposed deal structure could present for the buyer, and to diagnose, quantify and rectify (or at least explain) conditions that could give the buyer negotiating leverage, such insufficient working capital, historically low levels of capital and maintenance spending, strained supplier relationships, adverse margin or price trends, and projections that do not make sense given historical results. Often, bridges between past and projected results can be built simply by adding back the difference between actual and allocated costs.

For example, a media company subsidiary initially projected that EBITDA would increase 19 percent in the current year after rising only 12 and 8 percent in the previous two years. But when allocations and expenses that would be redundant to the buyer were removed, EBITDA would actually increase 21 percent in the current year versus 16 and 19 percent in the two prior years – proof that the division had performed much more consistently than management accounts indicated.

Extracting and presenting financial information that accurately reflects a target’s value gets more complicated when the target is a carve-out that doesn’t have separate financials. “Carve-out” is a generic term for any transaction that separates a smaller entity from a larger, consolidated business. Such transactions include sales of product lines, spin-offs [with or without IPOs], split-offs, equity carve-outs or the creation of tracking stock.

The overall goal of carve-out accounting is to present the historical financial results of the separated business as if it always has been a stand-alone company. This entails apportioning earnings, profits and the impact of past acquisitions and divestitures, as well as all costs of doing business including direct expenses such as selling costs; overhead such as office rent; corporate services like accounting, legal and marketing; and shared expenses such as pensions and benefits, insurance, taxes, impairment charges, debt and interest. As it is not always possible to attribute specific expenses to a carve-out entity, the SEC allows companies to allocate such costs using the incremental or proportional cost method, provided management explains the method used and asserts that it is reasonable.

Carve-out accounting requires considerable judgment, as no specific guidance governs the composition of a carved-out entity, and the sum of the parts does not equal the whole. It is therefore advisable to engage a divestiture advisor as soon as the decision to pursue such a transaction has been made. A divestiture advisor can help a firm uncover and explain information gaps, resolve technical accounting issues, and adopt a deal structure that reduces tax consequences for buyer and seller. They can also supply specialized resources such as actuaries to handle pension allocations and risk management professionals to estimate stand-alone insurance costs and obligations. By identifying potential deal-breakers early, recommending remediation strategies, ensuring that all the numbers hang together, and advising on the management of the entire sales process, divestiture advisors free deal principals to spend their time where it adds the most value, on marketing the deal to a select group of prospective buyers.

Carve-out financial statements in and of themselves will not suffice in all cases. They must be audited if the divestiture target will raise money through an IPO or public debt offering. When the target would represent a significant acquisition by a US public company, carve-out financial statements must not only be audited, but may also have to demonstrate Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 readiness, or at least identify where the control gaps lie and how they might be resolved. Similarly, if the prospective buyer is a European or Asian multinational, a private equity firm may have to present carve-out information according to International Financial

Reporting Standards (IFRS) and be prepared to address any unexpected differences between IFRS and US GAAP results. Taking these steps early in the divestiture process can strengthen the seller’s position by expanding the universe of willing buyers and increasing the likelihood of a smooth close with no last minute “surprises”.

Should an IPO ensue, a divestiture advisor can also help portfolio company management avoid the pitfalls of the registration process by anticipating and advising on the resolution of issues likely to surface during the SEC’s review, issues that can lead to an embarrassing restatement late in the process when the consequences are material to the deal.

3. Transition considerations

An actual carve-out involves the segregation and transition of certain previously shared corporate systems and services from the seller to the buyer. While perhaps not a priority in a seller’s market, developing a plan to meet the buyer’s transition service needs in a smooth and cost-effective manner can pave the way for a speedy and lucrative sale, especially when the assets being sold are less than prime or the market has passed its peak. Planning a smooth transition entails:

• Conducting a gap analysis that evaluates each prospective buyer’s operating issues and transitional service requirements against the divestiture target’s current operations and support functions;

• Reviewing the estimated cost of transitional services, one- time charges, and stranded costs;

• Assessing transferability issues with contracts and licenses; and

• Providing guidance on the critical components to include in transition service agreements (eg. service levels, dispute resolution, confidentiality, termination rights).

A transition services plan will describe the buyer’s Day 1 requirements, and spell out service levels, associated costs, and the recommended project management structure, along with a timeline for transitioning people and services. It will also address the seller’s stranded cost issues and present a run-off plan for non-transitioned assets including facilities, systems, contracts and other assets. Put simply, a well-designed transition services arrangement can add value for buyer and seller alike, making it more likely that the buyer will have a smoother transition to ownership, and giving the seller additional leverage during the negotiating process.

Enhancing the divestiture process may not seem like a priority when so many corporate and financial buyers have record levels of cash to invest in acquisitions. But firms who realize and plan for the more complex strategic, accounting and transition challenges likely to face future sellers will indeed reap the rewards that come to early birds.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter