Publications Revisiting And Reinforcing The Farmers Fox Theory: A Study (Test) Of Three Cases Of Cross-Border Inbound Acquisition Transactions

- Publications

Revisiting And Reinforcing The Farmers Fox Theory: A Study (Test) Of Three Cases Of Cross-Border Inbound Acquisition Transactions

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By K.S. Reddy, En Xie, Rajat Agrawal

Abstract

This paper aims to revisit and reinforce the early development of Farmers Fox Theory (Reddy et al., 2014a) by analysing three cases in the cross-border inbound acquisitions stream. A qualitative case method is adopted to explore the findings from the sample cases, which are the Vodafone–Hutchison telecom deal, the Bharti Airtel–MTN broken telecom deal, and the Vedanta–Cairn India oil deal. We highlight discussions on organizational factors, due diligence issues, deal characteristics, and country-specific determinants. Importantly, we test various theories propounded in the economics and management literature, and establish an interdisciplinary setting to both redefine the theory and reframe the propositions. The study eventually suggests that government officials’ erratic nature and the ruling political party’s influence were found to be severe in foreign inward deals characterized by a higher bid value, a listed target company, cash payments, and stronger government control in the industry. The findings of this research not only help researchers in strategy and international business but also managers participating in cross-border negotiations.

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical underpinnings

From the lens of development economics theory, international organizations and economic researchers have classified the given economic condition into the two groups of developed and developing countries. While supporting this streak, scholars from sociology, political, and legal studies have improved the definition of the economy on the basis of regulatory governance and political institutions. The two approaches suggest that developed economies have better quality laws, regulations, and institutions, which results in rich economic performance. In contrast, developing economies are characterized by poor economic results, lower quality institutions, no significant expertise in public administration, highly corrupt government officials, erratic behaviour of institutions, and high political intervention. In this vein, Lucas (1990) postulated ‘why capital does not flow from rich to poor countries’ and suggested that the weak institutional environment is one of the important determinants of insufficient capital flows from rich to poor nations. We propose that this postulation represents an institutional dichotomous characteristic of a developing economy, which scholars coined the ‘Lucas paradox’ (Alfaro et al., 2008). Theoretically, a given country has two investment options to doing business in other countries, namely direct international investment and portfolio investment. The direct investment allows the investor to enter a foreign country through a greenfield investment and/or mergers and acquisitions. Alternative entry mode choices include exporting, franchising, and licensing, among others.

Through the 1985–1991 economic and institutional policy reforms, developing countries have improved their economic indicators, regulatory laws, and business culture, thereby attracting significant overseas investments in various industries. In other words, significant financial and non-financial benefits have spread from developed to developing economies through overseas investment reforms. For instance, the benefits are seen in business models, education, management expertise, technology, culture, living standards, and so forth. Following the globalization and liberalization programmes, the distance between countries has shortened, markets have integrated, and communication costs have declined sharply, together leading to the closer integration of societies (Stiglitz, 2004). At the same time, multinational corporations (MNCs) from developed economies have increased their investments in developing countries through the preferred method of foreign market entry of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) [in addition to greenfield investments]. This method offers numerous benefits, ranging from ownership to location advantages, and attracts significant risks, especially economic, regulatory, and political shocks (Bris and Cabolis, 2008, Kiymaz, 2009, Meschi and Métais, 2006 and Rossi and Volpin, 2004). For instance, the extant M&A research reported that 83% of deals failed to create shareholder value and 53% actually destroyed value (as cited in Marks and Mirvis, 2011:162). For international deals, the failure rate ranges from 45% to 67% (Mukherji et al., 2013). Yet, the world market for corporate control activities substantially improved during 1991–2012, particularly from the sixth merger wave starting in 2003 (Feito-Ruiz and Menéndez-Requejo, 2011). For example, the worldwide number of cross-border deals (deal value) increased at a massive growth rate of 241% (1360%), from 1582 (US$21.09 billion) in 1991 to 5400 (US$308.06 billion) in 2012. For the Asian market, sales in terms of number of deals (deal value) notably improved at a significant growth rate of 908% (1818%), from 79 (US$1.54 billion) in 1991 to 796 (US$29.48 billion) in 2012. Conversely, purchases in terms of number of deals (deal value) drastically increased at a considerable growth rate of 833% (3521%), from 82 (US$2.20 billion) in 1991 to 765 (US$79.78 billion) in 2012. However, the percentage of the value of cross-border deals arising from foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows for 1991–2012 grew at an average annual rate of 37% for worldwide countries and 13% for the Asian market (UNCTAD, 2013).

Herewith, we postulate that cross-border inward investments declined at a shocking rate for both the Asian and the Indian market, whereas outward investments massively increased given lower asset valuations in developed markets and to escape from home country institutional barriers (Reddy et al., 2014b and Witt and Lewin, 2007). In addition to mounting overseas acquisitions in emerging markets, we notice that inbound and outbound deals are often litigated or are induced by institutional shocks in the host country when they are characterized by higher valuation, cash payments, and strong government control over the industry. For instance, Zhang et al. (2011:226) reported that 68.7% of worldwide acquisition attempts were completed during 1982–2009, of which 210,183 deals were not completed (460,710 deals completed) out of 670,893 acquisition events. Thus, this paper intends to analyse those litigated inbound deals associated with the Asian emerging market of India.

Extant international business (IB) and finance studies found that a country’s constitutional framework, political and legal environment, bilateral trade relations, and culture play an important role in cross-border trade and investment deals for both ex-ante and ex-post performance. For example, Alguacil et al., 2011, Barbopoulos et al., 2012, Bris and Cabolis, 2008, Erel et al., 2012, Francis et al., 2008, di Giovanni, 2005, Huizinga and Voget, 2009 and Hur et al., 2011, and Rossi and Volpin (2004) suggested that legal infrastructure, corporate governance practices, financial markets development, the level of investor protection, the quality of accounting and reporting standards, and socio-cultural factors are the key determinants that affect the completion of cross-border M&A. Further, macroeconomic factors, including gross domestic product, the tax system and tax incentives, the exchange rate, and the inflation rate, have a significant impact on overseas acquisitions (Blonigen, 1997, Hebous et al., 2011, Pablo, 2009, Scholes and Wolfson, 1990 and Uddin and Boateng, 2011). Moskalev (2010) found that a number of overseas investment projects significantly improved with respect to the progress made by a host country’s legal enforcement of foreign investors. Importantly, local political events including general elections affect both inbound and outbound FDI flows (Ezeoha and Ogamba, 2010, Schöllhammer and Nigh, 1984 and Schöllhammer and Nigh, 1986), and physical distance affects foreign investments (Rose, 2000). Overall, value-creating strategies, such as mergers, acquisitions, and strategic joint ventures, promote corporate governance and institutional development (Alba et al., 2009 and Martynova and Renneboog, 2008b).

With these prior studies in mind, we examine cross-border inbound acquisitions to the emerging country of India through a legitimate method of qualitative research, that is, case study research. Thus, we engage in a deep investigation into why cross-border inbound deals in India are frequently litigated. Before we explain the research framework, we present the factors that determine the success of cross-border M&As. Existing literature on cross-border M&A transactions suggests that firm-specific, deal-specific, and country-specific determinants influence both the negotiation process and post-merger integration. Then, we conduct the research and draw conclusions for the following broad research inquiry: how do host country characteristics affect the completion of international acquisition? Altogether, we attempt to revisit and reinforce the Farmers Fox Theory through an in-depth analysis (test) of three cases of cross-border inbound deals. Prior development of this theory was primarily propounded on the basis of evidence from a single case and inadequate testing of the theory (Reddy et al., 2014a).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The balance of Section 1 presents the research motivation, the research question, objectives, and scope and contribution. Section 2 describes the research design with a special emphasis on the multiple case study method. Section 3 discusses key insights drawn from the cross-case analysis. Section 4 describes testing the theory and the case proofs. Section 5 outlines the major research task, which is to revisit and reinforce the Farmers Fox Theory. Section 6 concludes this study.

1.2. Research motivation

A significant number of previous studies examined cross-border acquisitions through the lens of finance, economics, and strategic management, whereas a small number of studies investigated M&A in the IB field. By and large, academic and industry researchers analysed stock returns around the announcement, post-merger operating performance, and integration determinants. These studies inferred that on-going scholars have significant scope for studying pre-merger negotiations, determinants of deal completion, and the influence of host country institutional attributes. Indeed, seven tracks that appeared in the cross-border M&A stream motivated us to pursue this research. At the outset, foreign market entry choices are an important research focus in the IB and strategy fields (Chapman, 2003 and Hopkins, 1999). First, cross-border M&A largely remains underexplored compared with domestic M&A, and more theoretical and empirical research is needed to improve the current state of the literature (Bertrand and Betschinger, 2012, Hur et al., 2011 and Shimizu et al., 2004). Second, inadequate research exists on deal completion that enables the study of factors affecting the success of cross-border inbound acquisitions (Ahammad and Glaister, 2013, Reis et al., 2013 and Zhang et al., 2011). Third, most of the existing literature was built on the developed economies setting of the United States and the United Kingdom (Bertrand and Zuniga, 2006), which may be used to investigate deals in emerging economies to both support the existing theory and add new streaks to the literature (Barbopoulos et al., 2014, Bertrand and Betschinger, 2012, Francis et al., 2014, Kim, 2009, Malhotra et al., 2011 and Zhu, 2011). Fourth, the M&A stream is one of the prominent research areas that attracts scholars from various disciplines, including economics, strategy, finance, accounting, sociology, law, and politics. However, the field needs to be deeply analysed through the creation of an ‘interdisciplinary’ environment and not by engaging in ‘multidisciplinary research’ (Bengtsson and Larsson, 2012 and Cantwell and Brannen, 2011). Fifth, a vast quantity of M&A research is empirically driven and ignores qualitative research approaches. For example, Haleblian et al. (2009) reviewed the M&A research published between 1992 and 2007 and found that only 3% out of 167 research publication articles used the case study method. Thus, we adopted the qualitative case study method in this research. Sixth, most of the existing theories were developed on the basis of advanced countries’ behaviour; however, these theories should also be tested in emerging markets environments and a new theory should be developed in the given setting (Hoskisson et al., 2000).

Finally yet importantly, recent studies focused on and analysed how institutional distance, economic nationalism, and political behaviour affect the completion of cross-border acquisitions (Geppert et al., 2013, Lin et al., 2009, Serdar Dinc and Erel, 2013, Wan and Wong, 2009, Zhang and He, 2014 and Zhang et al., 2011). In a recent survey paper, Ferreira et al. (2014) showed bibliometric results for the extant strategy and IB studies on M&A research during the 1980–2010 period. They mentioned that ‘institutional theory has been remarkably absent from M&A research …, and suggested that emerging markets institutional authorities’ behaviour and government intervention in overseas acquisitions’ could be most relevant for further research. In addition, an analysis of deals with India is important for several reasons (Lebedev et al., 2015, Mukherji et al., 2013, Peng et al., 2008, Reddy et al., 2013 and Reddy, 2015). For example, emerging markets provide a unique setting (Bruton et al., 2008) in which to test existing theories because they characterize growing markets, improving economic performance, cheap labour, and some extent of liberalized regulations and governance standards [high levels of politicking, social crime, corruption, the erratic nature of government officials, and other foreignness issues]. In short, they behave differently from developed markets in many aspects, such as culture, technology, quality of law, income, living standards, and status of the economy (Stiglitz, 2004). Importantly, we find an emergent research interest in emerging countries such as China and India. For instance, a recent article by Xu and Meyer (2013) found that a total of 161 emerging economy-related papers were published during 2006–2010 compared with 99 in 2001–2005 (63% overall increase). Their results infer that stylish theoretical and empirical research is required on Indian businesses, which could shed light on strategies of emerging market firms, including outbound acquisitions, internationalization, and direct international investments – to name a few. In sum, this study aims to achieve research goals that likely recognize high-impact research in management studies (Alvesson and Sandberg, 2013).

1.3. Research synthesis

Qualitative case study investigations in the M&A stream are scanty, and the subject is largely dominated by quantitative research. At the same time, the analysis of cases between different borders requires adequate time and expertise, which depend on researcher quality. In this study, we adopted multi-case research to both test existing theories responsible for the M&A stream and to build a new theory from the emerging markets phenomenon. Nevertheless, a few studies examined international acquisitions involving emerging market enterprises, but they largely used empirical research tools (Agbloyor et al., 2013, Al Rahahleh and Wei, 2012, Chen et al., 2009, Francis et al., 2014 and Malhotra et al., 2011). Conversely, a small number of studies analysed international acquisition cases (primary/secondary data) in both developed and emerging markets (Geppert et al., 2013, Halsall, 2008, Meyer and Altenborg, 2007, Meyer and Altenborg, 2008 and Wan and Wong, 2009). Importantly, a significant knowledge gap exists in the M&A stream, which gives scholars the opportunity to investigate international acquisition processes and completions, especially when firms from developed markets seek to acquire firms in developing countries (Bertrand and Betschinger, 2012, Epstein, 2005, Reis et al., 2013, Serdar Dinc and Erel, 2013 and Zhang et al., 2011). Therefore, the Asian emerging market of India has been chosen as a sophisticated research setting for many reasons. Using archival data, we developed three cases in cross-border inbound acquisitions representing India and, thereby, designed a conjectural framework for a cross-case analysis. The cases selected for research meet the criteria of case study research. For instance, the cases should answer either why/how or both (Yin, 2003).

1.4. Research question

The objective of research should be a multi-level, multi-discipline ‘unified’ theory (Buckley and Lessard, 2005:595). Indeed, matching the methodology to the research question is central to any research effort (as cited in Nicholson and Kiel, 2007). Qualitative researchers suggested that the formulation of a research question is the most crucial phase in studies employing case study research (Tsang, 2013 and Yin, 2003). While supporting this streak, we also postulate that a given research question should be accompanied by research arguments that are unexplored in the literature. In contrast, finding a research gap or formulating a research question in the M&A subject is not easy given the massive size and extensive coverage of the literature since it was unveiled in the 19th century (Martynova and Renneboog, 2008a). Albeit, we find significant knowledge gaps when scholars started drawing attention to emerging markets behaviour, and such attention has increased appreciably after the special issue publication of the Academy of Management Journal ( Hoskisson et al., 2000). In particular, two special issue sequels suggested that scholars from developed and emerging markets are keen to examine different strategies that affect firm performance through the lens of different theories, namely the resource-based view, transaction cost economics, the eclectic paradigm, and institutional theory ( Wright et al., 2005 and Xu and Meyer, 2013). Importantly, recent studies examined institutional distance, political intervention, and nationalism in cross-border M&A transactions ( Ferreira et al., 2014, Meyer et al., 2009 and Reis et al., 2013), and this research trend/focus is expected to improve and attract other emerging markets scholars. For instance, Meyer et al. (2009) noted that institutional differences influence ‘how foreign firms adapt entry strategies when entering emerging countries’. Similarly, Serdar Dinc and Erel (2013) raised a research query: ‘do governments really resist the acquisition of domestic companies by foreign companies?’ Xu and Meyer (2013) also discussed institutional aspects and linked theory to the emerging markets context. In sum, we approach emerging markets through research on a qualitative case study that develops better sponsorship in formulating the following research question.

How (does) the host country institutional framework influence the completion of a cross-border inbound acquisition that focuses on the ‘success of the negotiations and the time required for completion’?

in turn,

How (does) a national weak regulatory and legal framework affect overseas inbound acquisitions, both referring to ‘acquirer/target and the host country’s sovereign income’?

Taking things forward, the study posits

Do we need a new theory to explain the statutory behaviour of emerging economies around inbound investments/acquisitions and the impact on their sovereign revenue?

1.5. Research objectives

The focal objective of this multi-case study research is to ‘build new theory’. To accomplish this goal, we set the following secondary or prerequisite tasks on the basis of the extant literature that addresses cross-border M&A, the phenomenon related to emerging market India, and the cases chosen for research:

♦ To examine the host country’s institutional laws that uncover an international taxation plea in a completed cross-border inbound acquisition;

♦ To investigate the impact of financial markets regulations and provisions on border-crossing inbound deals that result in delays, and then are completed or are unsuccessful;

♦ To study the adverse behaviour of public administration and political intervention in overseas inbound deals that became delayed, and then are completed or are unsuccessful; and

♦ To test existing theories propounded in various disciplines while supporting adequate case(s) evidence.

In addition to reinforcing the theory, we also suggest testable propositions for initiating further research on cross-border M&A in other emerging market settings.

1.6. Research scope and contribution

It is worth stating that the M&A field is an interdisciplinary event, which allows a scholar to study a particular knowledge gap with an in-depth focus that enriches the literature by focussing on different disciplines. The scope of the research is prone to be broad and engages in an analysis from the lens of different disciplines – economics, corporate finance, strategic management, organization studies, sociology, law, and, importantly, IB. For example, we test novel theories propounded in various disciplines, such as the resource-based view theory, liability of foreignness, information asymmetry theory, market efficiency theory, institutional theory, organizational learning theory, and so forth. Because of the widespread theoretical backdrop, the research contribution is significant and vital to the current state of knowledge. Thus, we examine the impact of the host country’s institutional environment (e.g. financial markets, and taxation, and political involvement) on cross-border inbound acquisitions for various reasons: deals characterize higher valuations and cash payments, the acquirer belongs to a developed country, and the industry is largely controlled by public sector enterprises. We also postulate how a weak regulatory system adversely affects a given host country’s sovereign revenue whilst promising benefits to the acquirer and/or target firm in overseas inbound deals.

This unique effort entails using qualitative case research to analyse the impact of institutional determinants on cross-border inbound acquisitions when hosted by the emerging market of India. Nevertheless, this study is among the few to examine Indian M&A deals (domestic/overseas) through case study research because it tests existing theory and builds new theory. Further, this study is exceptional in the extensive M&A literature because of its interdisciplinary setting and its theory building through the new multi-case research procedure. Therefore, the contribution of this research is fourfold. First, we consider the emerging market behaviour of India as a potential research setting to study the impact of institutional and legal environments on cross-border deals. Second, a multi-case investigation enhances the current knowledge on pre-merger negotiations (deal completion) when transactions occur between developed and developing countries, and addresses higher valuations, cash payments, and more government control in the industry. Third, we discover a new method of multi-case research design to both overcome research obstacles (e.g. data collection) and study the emerging markets phenomenon. Lastly, we propose a new theory and suggest propositions for enhancing the current knowledge and initiating further research on the ‘impact of institutional distance and political intervention in cross-border deals’, which in turn should explain the ‘host or home country economic benefits’. In addition, the findings of the research have strategic implications for multinational managers, economic policy, the legal framework, and society.

2. Research design: multiple case study method

Unlike empirical studies, qualitative research has had a markedly different methodological rhythm for various reasons, including rigour and quality. Indeed, qualitative researchers review the exhaustive literature in the given field to strengthen their research arguments. Qualitative research is a form of scientific inquiry that aims to understand ‘complex social processes … and characterizes organizational processes, dynamics, and describes social interactions and elicits individual attitudes and preferences’ (Curry et al., 2009:1442–1443). Qualitative research is helpful in business research when analysing critical issues that remain unclear in quantitative research (Eriksson and Kovalainen, 2008). However, qualitative research has been underutilized in the management discipline. For instance, regrettably, IB is still depicted as ‘empirically driven, a theoretical field that fails to go much beyond the descriptive’ (Shenkar, 2004:165). Therefore, we chose qualitative case study research to achieve our research goals. Case study research (CSR) aims to investigate and analyse the unique nature of an organizational environment in a real-life setting on the basis of single or multiple cases that are carefully bounded by time and place (Conrad and Serlin, 2006, Miles and Huberman, 1994, Stake, 1995, Yin, 1994 and Yin, 2003). When commenting on sampling, Yin (1994) suggested that case researchers might use a single case or multiple cases that depend on the purpose of the research – whether testing or developing theory. The problem with single cases is the limitations in generalizability and several information-processing biases (Eisenhardt, 1989). Importantly, case studies provide rich and in-depth evidence with which to develop theories and offer theoretical constructs and testable propositions in an emergent research area. Subsequent studies advanced Eisenhardt’s concept (Bengtsson and Larsson, 2012, Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007 and Hoon, 2013). Whereas theory building from multiple cases typically yields theories that are more robust, generalizable, and testable than the single-case research … ‘theory-building research using cases typically answers questions addressing “how” and “why” in unexplored research areas’ (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). The case study method has become an increasingly popular and relevant research strategy in business management studies (Hoon, 2013). In sum, the case study method is the best recognized and a highly motivated approach that allows a researcher to deeply study and ‘look up’ critical and complicated business transactions – unsuccessful M&A deals. For example, Fang et al. (2004) and Meyer and Altenborg, 2007 and Meyer and Altenborg, 2008 analysed the failed merger between two Scandinavian telecom companies: Telia of Sweden and Telenor of Norway. Wan and Wong (2009) analysed an unsuccessful takeover of Unocal (United States) by CNOOC‘s (China). Conversely, a few studies examined multiple cases using various theoretical frameworks (Geppert et al., 2013, Liu and Zhang, 2014 and Riad and Vaara, 2011). At the outset, extant social sciences and theoretical management concepts and empirical literature have been largely determined on the basis of western (developed) economies’ institutional context. In the recent past, many researchers argued that western theories are inadequate for studying the emerging markets phenomenon and described the problems related to data collection, data analysis, and theory development. We also (experience) find that major problems exist in emerging markets (e.g. India, Pakistan) that are accountable for data collection, especially primary data (interview/survey) (Dieleman and Sachs, 2008, Dhanaraj and Khanna, 2011, Hoskisson et al., 2000, Malik and Kotabe, 2009 and Reddy and Agrawal, 2012). The quality of either qualitative research or quantitative research depends on the rigour (or approachability) of the research carried out by the researcher in a given setting (Yin, 1994 and Yin, 2003). In sum, qualitative case researchers argued that sample cases or units of analysis should offer a sophisticated research setting to test extant theory and to improve/build the theory. Indeed, a multi-case research design provides a significant theoretical backdrop relative to the single case environment. We adopted the multi-case research method and developed ‘special’ tasks to build new theory and enhance the knowledge of the M&A field. 2.1. Sample cases The focal research question in this study is: does a host country’s weak regulatory system benefit both the acquirer and the target firm in cross-border (inbound) acquisitions? To enhance this question, we derive two equated sub-research questions, i.e. why and how (Yin, 2003). In the current setting, why were cross-border inbound acquisition deals delayed or called off? How does a host country’s regulatory system affect the acquirer and the target firms involved in cross-border inbound transactions? To examine these research questions, an interdisciplinary theoretical background is being set up (for suggestions and framework: see Cheng et al., 2009; Reddy, 2014). Following the pattern matching observations of cases, we select three deals that were particularly affected by the host country’s institutional laws for mergers, acquisitions, listing norms, and international taxation. The cases were the Vodafone–Hutchison tax litigation deal and the Bharti Airtel–MTN broken deal in the telecom sector, and the Vedanta–Cairn India delayed deal in oil and gas exploration. Thus, the common pattern in all three cases is regulatory laws and provisions, and political intervention. To the best of our knowledge from the media, two of the three cases were highly represented in all leading TV channels (e.g. CNBC, TV18, and ET Now) and finance-related daily news (e.g. Economic Times, Business Standard, Business Line, and Financial Express). Further, they appeared in international finance-related dailies, such as the Financial Times and Reuters, and in official reports from leading accounting agencies, such as KPMG, Deloitte, and other host-country registered trading brokers. Finally yet importantly, one of the three cases was long-time awaited and challenged a tax petition in the apex court of India. Moreover, emergent research on cross-border M&As’ ‘completion’ in emerging markets (Muehlfeld et al., 2012, Zhang and He, 2014 and Zhang et al., 2011) and economic nationalism and institutional factors around international direct investments (Dikova et al., 2010 and Serdar Dinc and Erel, 2013) have stimulated a study that investigates ‘complex, intercultural, institutional and cross-border negotiations’ for both new knowledge creation and theory development. In fact, a study on merger/acquisition failure deals in the international setting provides a unique setup in which to perform in-depth and systematic analysis of a single case or across cases. For example, Fang et al. (2004) and Meyer and Altenborg, 2007 and Meyer and Altenborg, 2008 explored the problems of incompatible strategies (national cultures) and the disintegrating effects of equality in foreign mergers using a failed merger between two state-owned telecom firms in Scandinavian countries, i.e. Telia of Sweden and Telenor of Norway. Wan and Wong (2009) investigated the economic impact of political barriers and deeply analysed the stock price changes of other U.S. oil firms attributable to CNOOC’s (China) unsuccessful takeover of Unocal (United States). Similarly, three cross-border inbound acquisitions were critically examined in light of the host country’s institutional setup and the acquiring firms’ behaviour. Unlike previous studies, the uniqueness of the deals are as follows: (i) a deal that completed, but was litigated for long-time in the sample country’s jurisdiction because of international taxes and succeeded in favour of the acquirer, (ii) a deal that engaged in extended merger talks in the first round, was renegotiated in the second round, and then was called off because of the deal structure, national identity, and dual listing norms, and (iii) a deal that was delayed and slowly materialized because of contract laws and open offers issues. In particular, two deals were related to the telecom business and the remaining deal was associated with the oil and gas industry. A common thread in all three inbound-acquisition deals was weak institutional laws and procedures, and erratic behaviour by government officials. In essence, big-capitalists, politicians, and the government more closely influence telecom and capital goods industries compared with other businesses, which usually captures significant asymmetric information. In this vein, Wan and Wong (2009) mentioned that ‘barriers are particularly high in the energy sector but low in sectors not involving critical infrastructure’. As such, the sample cases provide a rich setting in which to study institutional laws, political intervention, and government involvement in inbound direct investment deals. The main characteristics of the sample cases were as follows: (a) cross-border inbound acquisitions involving India as the host country, (b) two cases related to the telecom business and the remaining case related to oil and gas exploration, (c) one case out of two delayed cases was found to be successful and the remaining case was legally challenged after completion, (d) all cases received public attention (were paid special attention), and (e) all cases were affected by the host country’s institutional, legal, political, and financial markets environment. 2.2. Sampling time The sampling time of the cases is as follows:

• Case 1: Starting date December 2006 – Closing date March 2012, for a total sampling time of 64 months (backward search and observation);

• Case 2: Starting date February 2008 – Closing date November 2009, for a total sampling time of 22 months (backward search); and

• Case 3: Starting date August 2010 – Closing date December 2011, for a total sampling time of 17 months (forward search and observation).

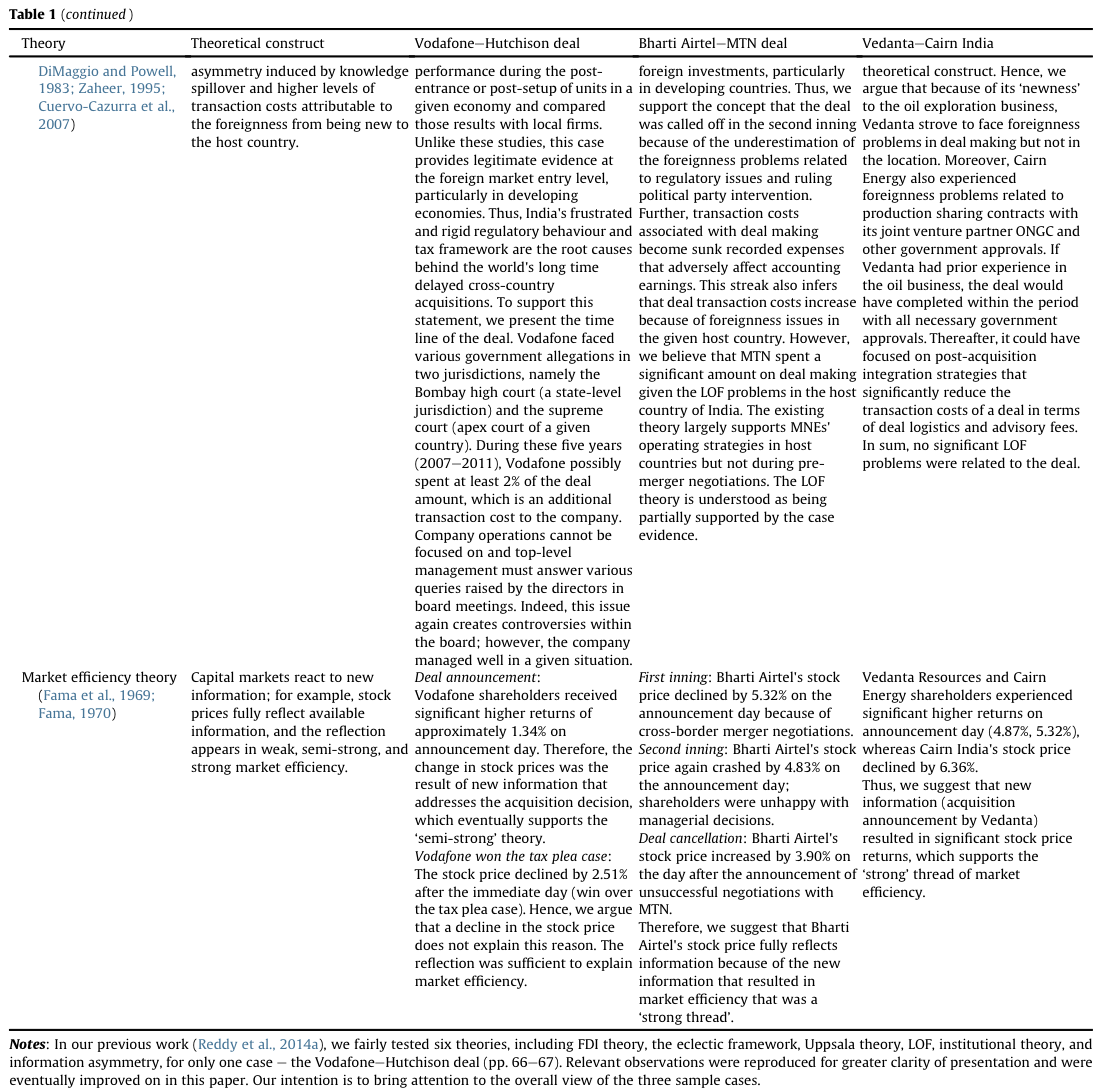

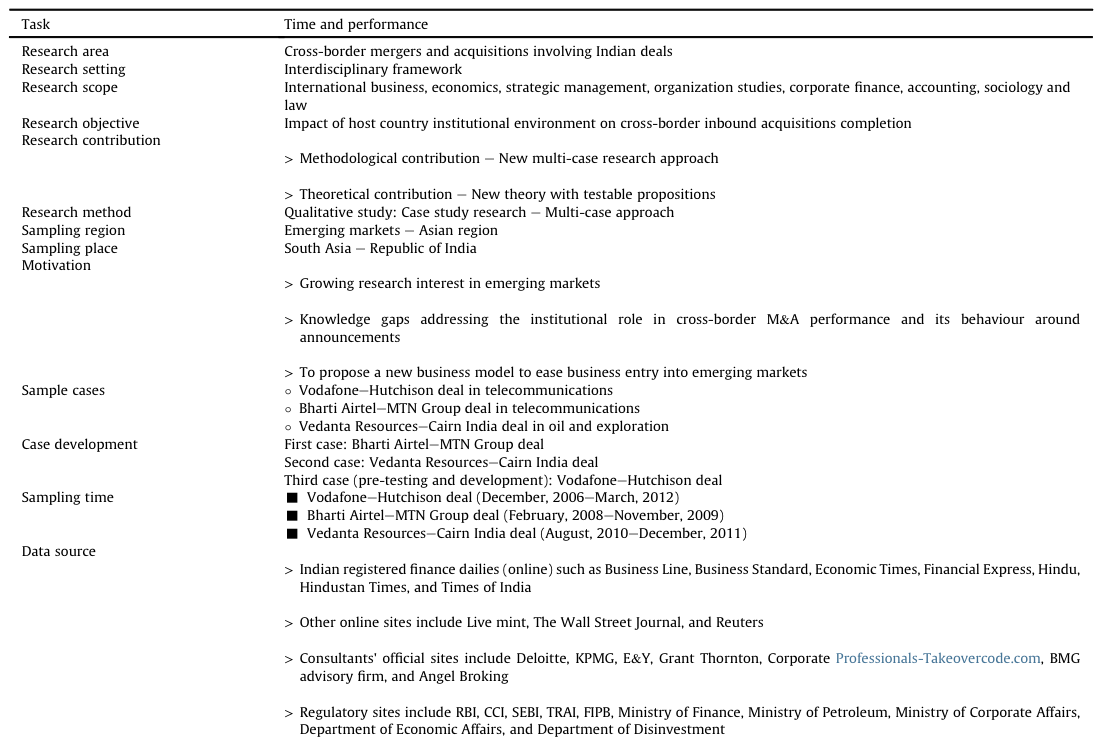

The starting date indicates the date on which the deal announcement first appeared in any of the national finance dailies (e.g. Economic Times, Business Line, Financial Express, or Business Standard). It should be noted that news might have appeared before the acquirer made a formal announcement. The closing date is the date on which negative news/a final decision was published in any the previously mentioned finance dailies. We also checked the news with each respected company’s web news, notices, and reports (e.g. annual reports) to confirm the authenticity of the data. In fact, we created a Google Alerts to immediately obtain the news about specific deals as they appeared on the World Wide Web. Thus, the interval time of news delivery is ‘daily’. The total sampling time represents ‘five years and four months’. 2.3. Case study protocol A case study protocol records a set of actions and procedures adopted in the given case method to ensure the trustworthiness of the findings. For example, Yin (1994:41) suggested that researchers should develop a well-considered set of actions rather than use ‘subjective’ judgements. The development of these actions, such as acknowledging the mail, is useful particularly in a qualitative research environment (Gibbert and Ruigrok, 2010). We cautiously recorded every event of the doctoral research in electronic files, including sample cases, case development, sampling time, data source, data collection, case writing, and case publications, among others (see Appendix A).

3. Cross-case analysis: key discussions

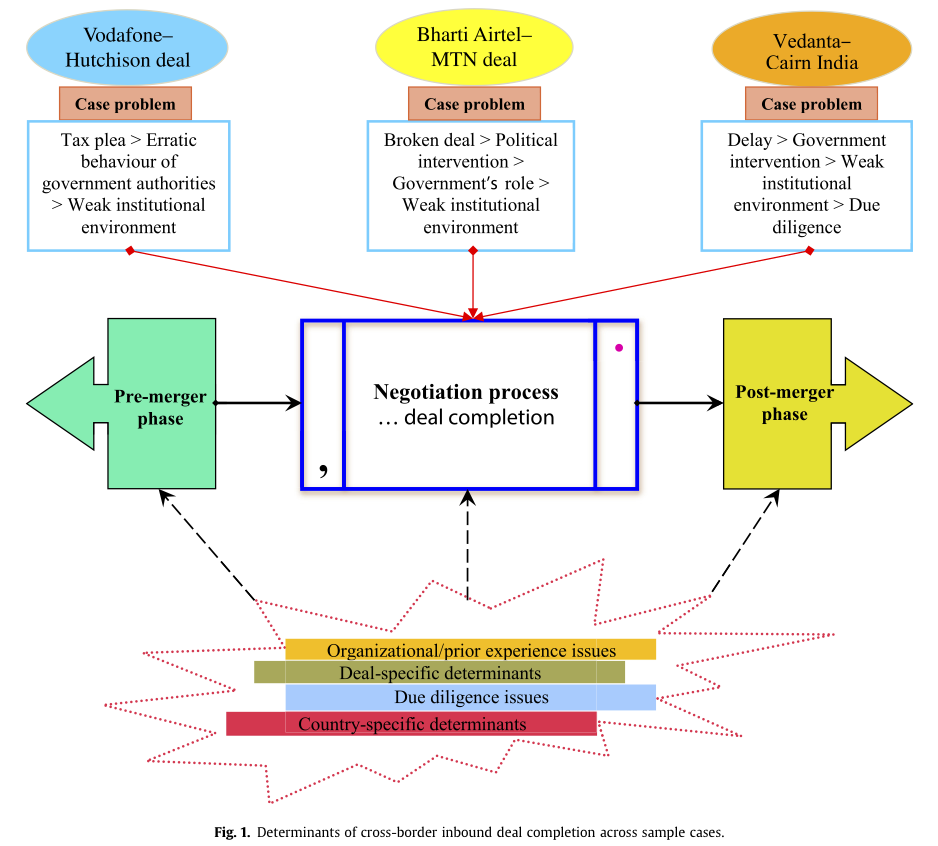

Using the extant literature and multiple case analyses, we seek to discuss the key factors that determine the success or failure of an international acquisition. However, we notice that some findings are common across nations irrespective of the developed or developing status of the host country, whereas few observations are ‘special’ if the acquisitions are hosted by emerging economies such as India. Therefore, acquiring firm managers and M&A advisory firms should pay more attention to these special factors when a target firm is associated with a developing nation. We discuss the common and the special determinants through four strands: organizational issues, deal characteristics, due diligence, and external barriers (Fig. 1).

3.1. Organizational issues

Prior researchers suggested that deal completion is also influenced by firm-specific variables, such as relevant business, firm size, management expertise, and previous acquisition experience. We support the theoretical notion that overseas acquisition success not only depends on firm size and related businesses but also on a firm’s previous acquisition experience in the related business, market, and level. For example, the Bharti Airtel–MTN telecom deal was called off because of both external and internal factors. Internal factors, such as the firm’s international outlook and prior deal experience, might cause the deal to be delayed and/or not completed. Moreover, although deep pockets and business expertise in the telecom business existed, the deal became unsuccessful because of a lack of professionalism in deal making. In contrast, the Vedanta–Cairn India deal was delayed but was later completed after all government approvals were obtained. We realize that deals are also delayed if the acquiring firm has no experience in the relevant business of the target firm. However, diversified business groups achieve deal success because of their conglomerate’s diversification, group size, and availability of cash reserves. Therefore, large companies can sustain themselves in both related and unrelated businesses. Importantly, firms participating in overseas acquisitions involving emerging economies will gain relevant experience in deal making, acquire additional skills to complete the proposed deal, and learn from the failures and successes of negotiations. Further, the experience gained in emerging economies is expected to result in positive future acquisition performance. In sum, the acquiring firm that has prior acquisition experience, an international outlook, related businesses, and deep pockets may record success in subsequent deals, such as the Vodafone–Hutchison deal. In this case, we suggest that these success factors enabled Vodafone to successfully complete the Hutchison acquisition, prepare for entry into India, and win the tax plea even after a long delay in judgement. Nevertheless, organizations do not stop their learning because of success or failure but, instead, learn and gain knowledge continuously to overcome various obstacles in the future.

3.2. Deal-specific issues

Few studies suggested that a deal’s structure in terms of type of deal, payment structure, and M&A advisors’ expertise affects its completion. We seek to answer why (how) a deal’s structure determines its success. For the case analysis, deal structure has been discussed more as an ‘ownership strategy’ in finance rather than a ‘general strategy’ in strategic management or IB. We provide two reasons for this classification. Firstly, what percentage of equity should be acquired to gain control over the target firm? Secondly, what payment mode (cash, stock, or both) should the acquiring firm adopt without diluting ownership and control benefits? Further, the payment mode is influenced by the accounting and taxation laws in the given host economy (Epstein, 2005). Logically, if the acquiring firm wants full control over the target firm, then it should pay cash to the target firm’s shareholders. Assuming that the acquiring firm paid or issued stock to the target firm’s shareholders, then one could see the dilution in ownership that leads to questions of who has better control over the target firm and who will enjoy the firm’s earnings. For example, the Bharti Airtel–MTN telecom deal failed to materialize because of its deal structure. Both firms wanted to control the post-merger entity by giving the company a dual listing in India and South Africa. In addition to the benefits of a dual listing, both firms would face agency and information asymmetry problems. The impact of the dual listing would cause payment options to change, thereby attracting regulatory obstacles (e.g. open offers) and other issues (e.g. political intervention). If they could have perceived an acquisition strategy other than a merger, the deal would have completed with a better ownership and control mechanism, a cash payment, a non-compete agreement, and others. Conversely, because of prior international deal experience in developed economies, Vodafone avoided paying capital gain taxes to the Indian government after acquiring the Hutchison equity stake in CGP Investments, thus controlling Hutchison-Essar Ltd. From these observations, we suggest that good deals save significant transaction costs, whereas bad deals create numerous inherent problems that lead to broken pre-merger negotiations or post-merger integration. Following the Vodafone strategy, Vedanta Resources obtained controlling rights in Cairn India by acquiring Cairn Energy‘s equity stake. Hence, Vedanta could not avoid paying taxes to the government because of the greenfield investment made by Cairn Energy when it entered India. Therefore, we suggest that the acquiring firm’s managers and M&A advisory firms should be aware of the qualitative attributes of deal characteristics, such as ownership and control benefits, payment modes, non-compete agreements, cross-listings, break-up fees, and so forth. In addition, M&A advisors should work to complete deals that lead to significant advisory fees and commissions.

3.3. Due diligence issues

Previous studies suggested that due diligence issues also determine the success of deals in domestic and overseas settings. Due diligence is an examination of the target’s business for various reasons, including capital structure, ownership rights, product profiles, contingent contracts, legal disputes, taxation disputes, and financial performance (Epstein, 2005). In the given research, the Vedanta–Cairn India deal attracted due diligence problems, particularly the royalty payment controversy between Cairn Energy, ONGC, and the Ministry of Petroleum. Further, the deal was delayed because ONGC has pre-emptive rights in one of the oil fields owned by Cairn India. For that reason, Cairn Energy strove to obtain approvals from the respective government departments and the petroleum ministry. Thus, we suggest that acquiring firm managers should not exploit funds at the expense of shareholder commitment. In other words, the M&A advisory team and the acquiring firm’s due diligence team should inspect and clarify any issues before finalizing, agreeing to, and transferring payment.

3.4. Country-specific determinants

Accessible literature on direct international investments and overseas M&As performed in various national settings found that the economic, financial, legal, regulatory, governmental, political, cultural, and geographical factors affect both pre-acquisition completion and post-acquisition integration. In particular, the behaviour of the host country’s government authorities, strong political institutions cum political stability, rule of law, control of corruption, and white collar crimes and regulatory quality together create a favourable institutional environment that allows foreign firms to invest in the given economy (Reis et al., 2013 and Stein and Daude, 2001). At the same time, the environment allows foreign firms to reduce transaction costs during the market entry process. Reis et al. (2013) suggested that developed country MNCs must face institutional difficulties (law, corruption, crime, political intervention) when making deals with target firms in developing countries. For instance, a typical case in the Indian court system takes approximately 20 years to come to a final decision (as cited in Armour and Lele, 2008). As such, we examine foreign acquisitions at the acquisition process or deal completion stage. For example, two out of the three cases – Vodafone–Hutchison and Vedanta–Cairn India – faced external difficulties, such as underdeveloped laws, legal formalities, erratic behaviour of government officials, and political intervention. This streak supports the empirical finding of Reis et al. (2013) through the fact that both Vedanta and Vodafone were based in the developed country of the United Kingdom and then invested in the developing economy of India. Given its international outlook, prior deal experience, and management expertise, Vodafone and Vedanta triumphed over the regulatory hurdles and then successfully completed the deals. By and large, the Bharti Airtel–MTN deal faced severe institutional hurdles, such as an open offers programme, dual listing norms, and shareholder rights. The deal was called off ‘twice’ and, thereby, the companies decided not to renegotiate in the future. In this vein, we are not convinced that the cultural distance between India and South Africa truly influenced merger negotiations (because the two countries have good economic and social relations). If so, the deal should have been revoked in the first inning. Given the home country’s strict regulations, Bharti Airtel acquired Kuwait-based Zain Telecom and gained a business opportunity over the African market. On the basis of the case analysis, we suggest that government officials’ erratic nature and the ruling political party’s influence will be stronger in foreign inward deals characterized by higher bid values, a listed company, and cash payments. The strong reason behind such an influence could be a ‘personal financial and/or non-financial benefit’, which is behind the screen and under the table. Given the institutional dichotomy, inward acquisitions are typically delayed and/or fail without any public announcement being made. Lastly, bidding managers and M&A advisors should pay more attention to the host country’s ruling political party and other institutional factors when making long-term investments in countries such as India and China. Geographical factors such as distance and culture do not explain the sample cases.

4. Theory testing and case illustrations

Strategy, IB, and finance researchers explored the phenomenon of a firm reporting significant growth when choosing a corporate inorganic model versus an organic model. For instance, growth can be viewed in terms of synergies’ market share, profitability, competitive advantage, economies of scale, new market experiences, and so forth. The model identified in this research is an ‘acquisition’ and a cross-border deal. In addition, U.S.- and UK-based – and other developed-country-based – multinationals internationalized their operations, corporate ownership, and products and services through mergers and/or acquisitions. Similarly, recent research on emerging economies illustrated that emerging-market firms are adopting and, thereby, following past and current strategies of developed-country MNCs for survival and excellence.

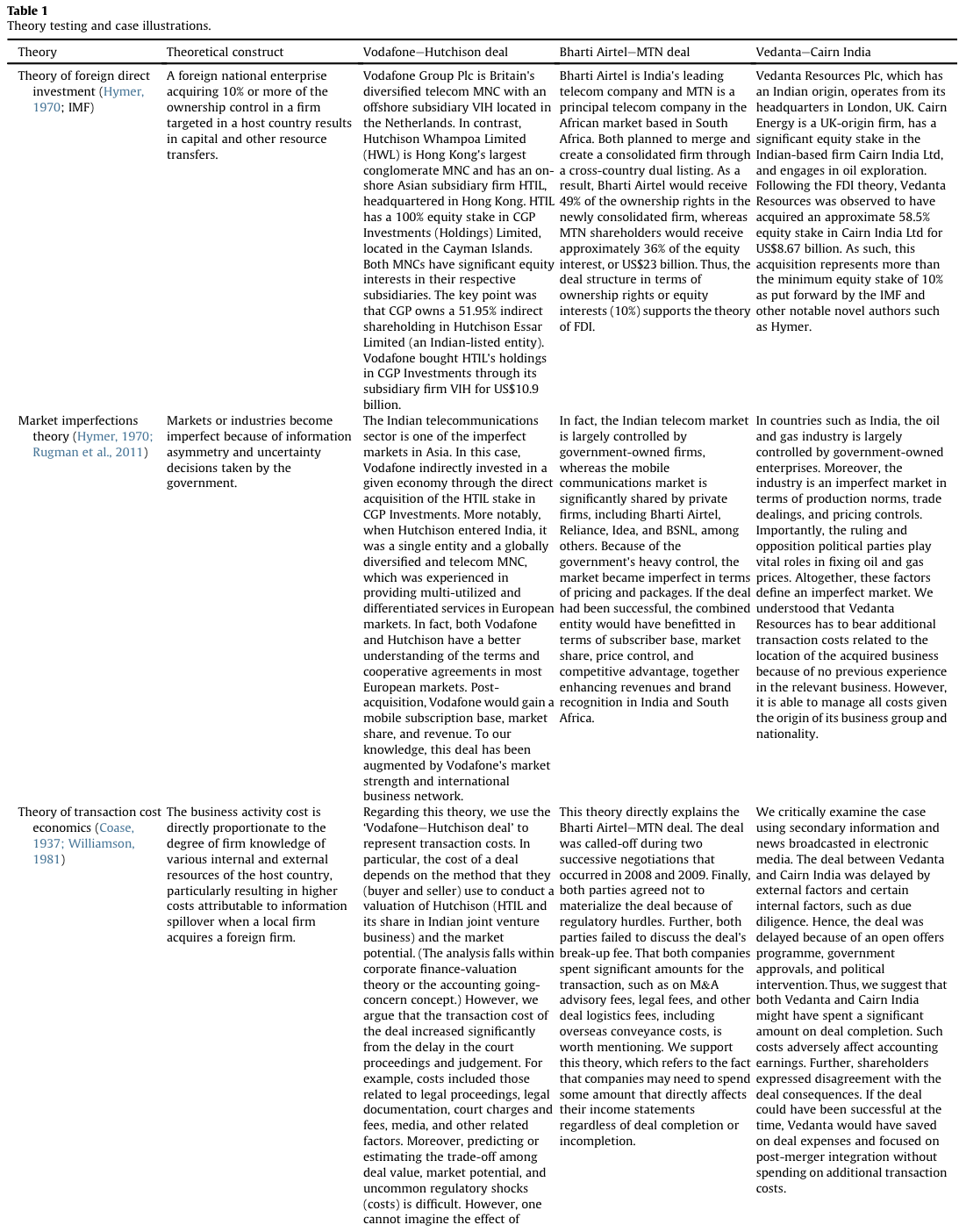

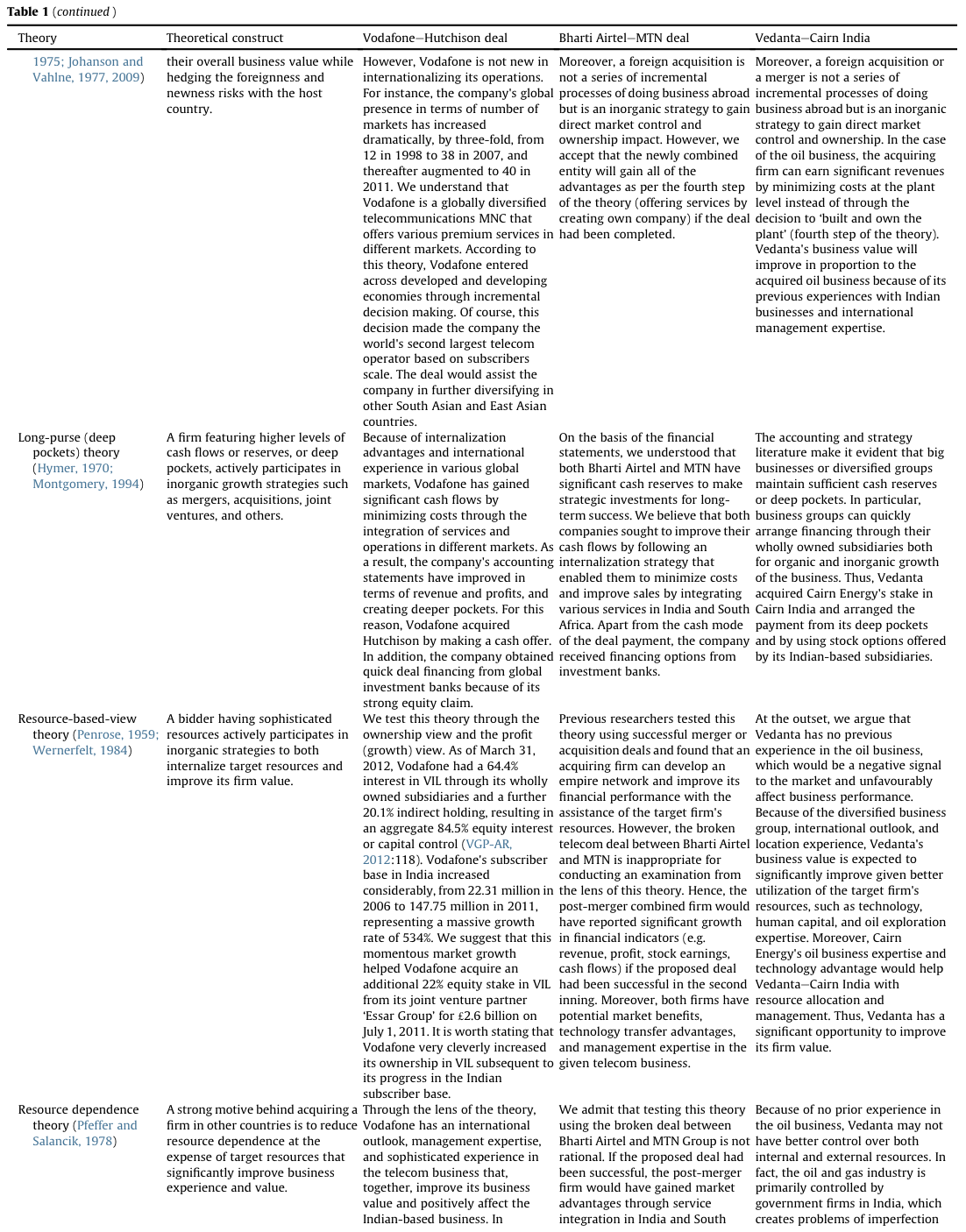

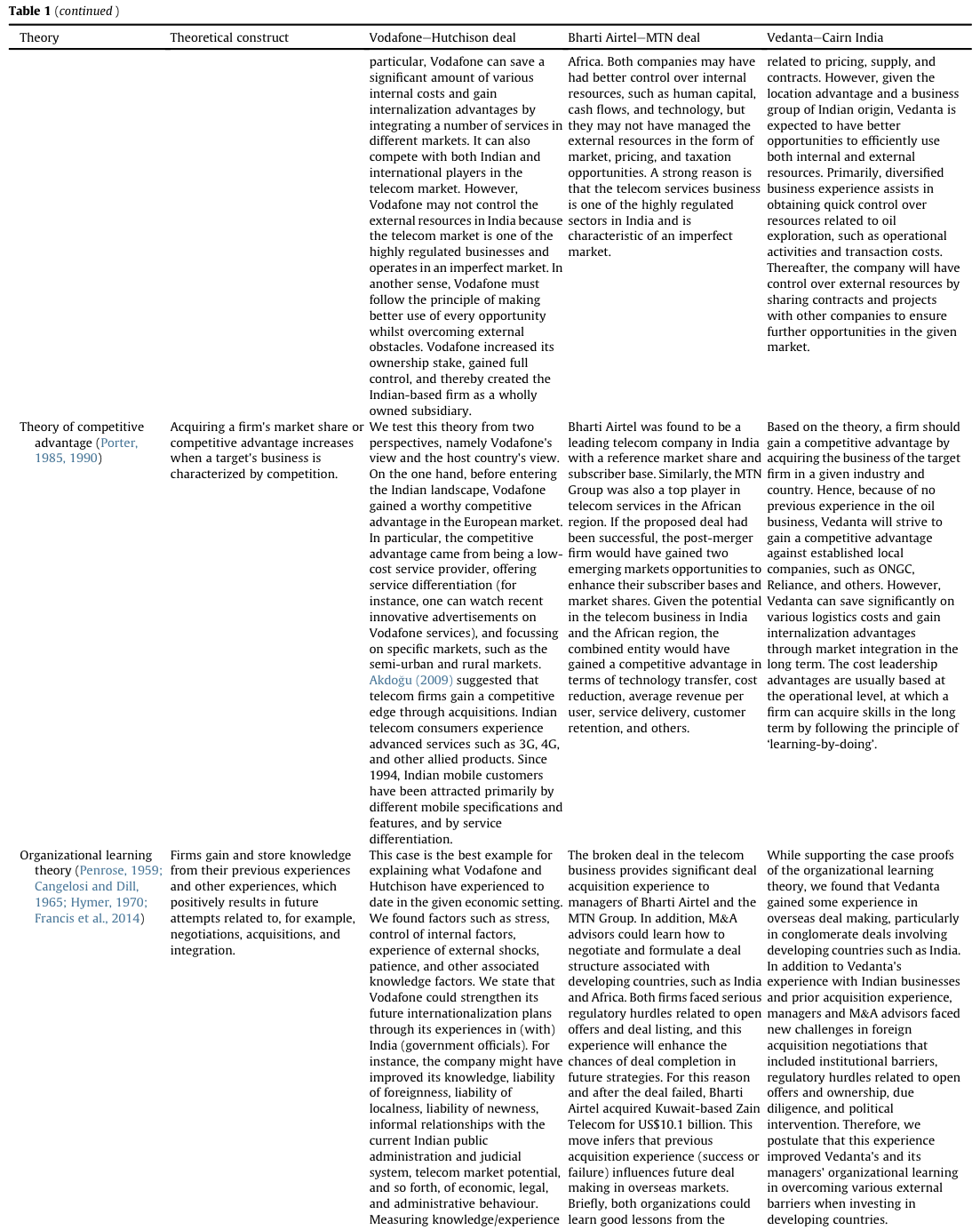

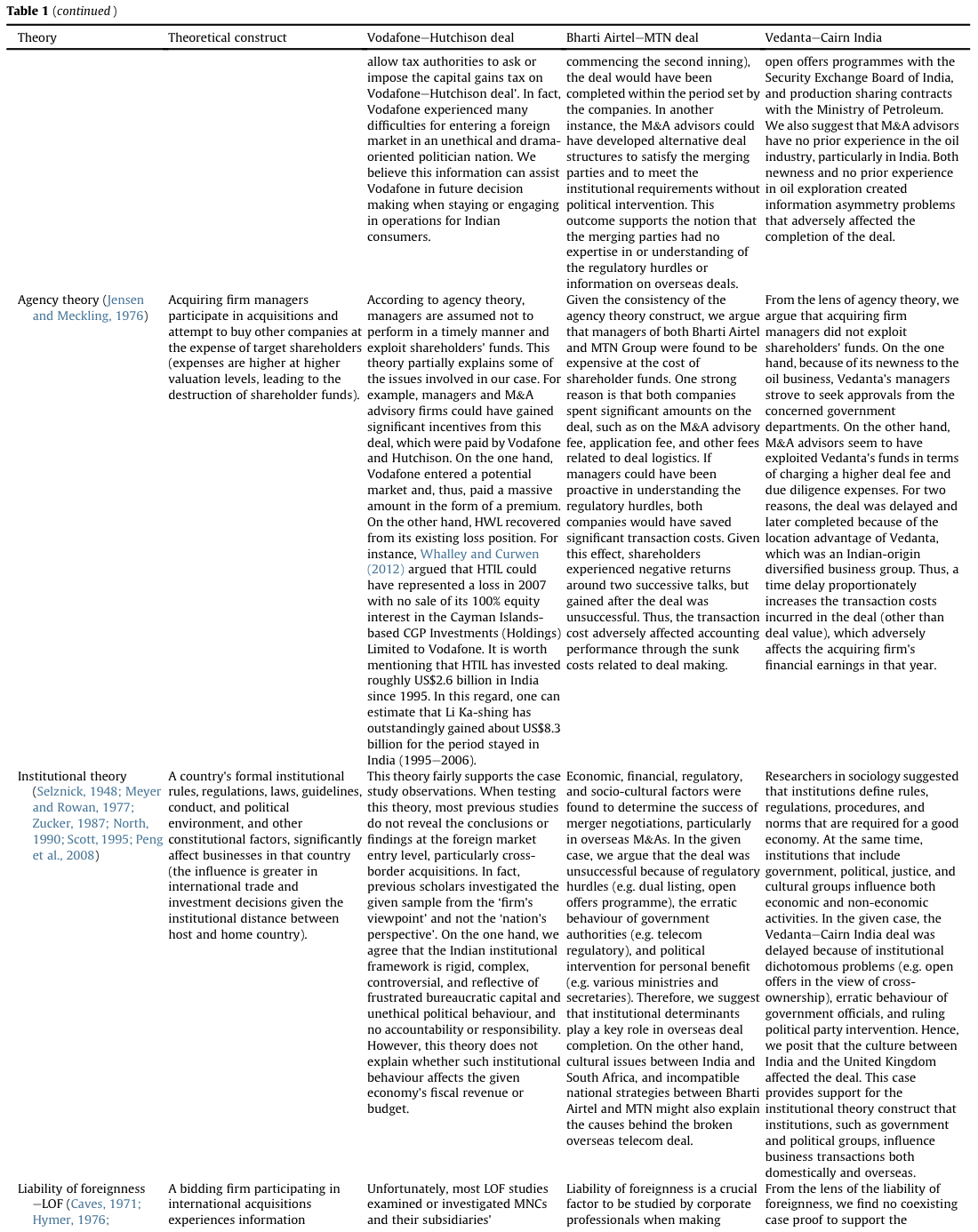

This section aims to test 17 theories propounded in different business research disciplines, such as the Caves and Hymer theory of FDI, Dunning’s eclectic theory, the Uppsala theory of firm internationalization, Penrose’s resource-based-view theory, North’s institutional theory, Hymer’s thought of liability of foreignness, Jensen and Meckling’s agency theory, and Fama’s market efficiency theory, to cite a few (Table 1). We also look up an important theorem of ‘learning-by-doing’ in organization studies. Special tasks such as pre-testing (Reddy et al., 2014a), revisiting the post-testing task, and reinforcing theoretical constructs in this paper will improve the current knowledge that refers to the impact of institutional distance on cross-border M&A completion.

5. Farmers Fox Theory: revisited and reinforced

As mentioned in previous sections, a few recent studies tested and advanced the knowledge of the resource-based view, transaction cost economics, and agency and institutional theories (Xu and Meyer, 2013). Albeit, scholars suggested that emerging markets represent unique settings that offer the ability to obtain fresh insights to expand the theory (Bruton et al., 2008) and to develop new theories and testable propositions. For example, Wright et al. (2005:24) suggested an important research argument: ‘to what extent do problems arising from institutional differences increase transaction and agency costs and lead to exit by foreign entrants?’ Similarly, Xu and Meyer (2013) also stressed the importance of studying institutional perspectives in foreign market entry strategies in emerging markets whilst linking theory to the context. Further, recent papers published in leading finance and IB journals discussed the significance of institutional distance and economic nationalism in cross-border M&As (Barbopoulos et al., 2014, Hur et al., 2011, Reis et al., 2013, Serdar Dinc and Erel, 2013, Wan, 2005 and Wang, 2013). Therefore, we realize that new theories based on the emerging markets phenomenon should draw more attention to the institutional environment and its impact on the internationalization process. In this vein, Hur et al. (2011) tested the hypothesis ‘the quality of host countries’ institutions positively affects the cross-border M&A inflows’. Nagano (2013) also tested the hypothesis that ‘an enhancement of IPR protection law in the host-country encourages inward greenfield FDI and that of SHR protection law promotes cross-border M&A’. Reis et al. (2013) propounded a few testable propositions in light of institutional distance and cross-border M&A completion.

With these studies in mind, we establish a triangular association between systemic multi-case analysis, extant M&A literature, and theory testing. Before introducing new theory, the case study protocol is to disclose missing threads in the existing literature. We find very few research questions, but they were largely unexplored in emerging markets phenomenon that raised new avenues to enhance the literature in IB, strategy, and economics. For example, Lucas (1990) argued, ‘why does not capital flow from developed (rich) to developing (poor) countries’, and developed the theorem using the Indian setting. Lucas postulated that developing countries were not able to receive investments from rich countries because of weak regulatory laws (e.g. investor protection, financial disclosures, ownership rights) and their poor implementation. Lucas mainly argued that sovereign risk (e.g. political) and asymmetric information are higher in poor countries because of improper laws and weaker regulatory enforcement that negatively affect foreign inflows when receiving from rich nations. Further, Lucas also discussed the external advantages of human capital (labour), technology transfers, and imperfect market conditions. Alfaro et al. (2008) empirically tested the theory and considered a sample of 50 countries during the 1971–1998 period and suggested that institutional quality has been a major determinant in explaining the Lucas paradox. In such cases, we argue that poor countries are losing significant economic (e.g. taxes) and non-economic incentives (e.g. skills and expertise) because of the erratic nature of their administration, political intervention, and unsecured investor rights. The missing link is that poor countries are allowing foreign investments but are severely losing economic benefits, such as revenue taxes, capital gains taxes, and border taxes, in addition to weak governance. This streak seems to be an old argument; however, no previous study postulated that a given country’s government needs to face economic (revenue) risk because of weak institutional laws. Thus, we seek to develop a new theory on the basis of the research question: how (does) a poor county hosting foreign investments undergo economic loss while profiting the host party (acquirer or target)? Indeed, some important arguments that previous scholars raised also support the research question. For instance, Reis et al. (2013) developed several theoretical constructs to explain how institutional distance (government, political, and social) affects the likelihood of completing an overseas deal. These constructs are propounded as the ‘Farmers Fox theory’, which postulates:

‘a given country’s weak (loopholes in) financial and tax regulatory system benefits both the acquirer and the target firm in cross-border acquisitions based on two assumptions: first, one must have some experience within the given economic and regulatory environment or some kind of alliance with a local firm; second, the other one should be new to the economy where the target firm is registered or associated. In the given situation, this economic behaviour adversely affects that country’s fiscal income or revenue’.

In other words, a country that characterizes weak institutional laws, a high level of corruption, severe politicking (ruling political party intervention), hosting foreign direct investments, or inviting foreign MNCs through the acquisition method may have to the record a loss of economic incentives such as international taxes, cross-listing fees, and taxes on overseas revenues. In that case, the acquirer and/or target should enjoy such economic benefits without paying for them to the sovereign of the host country – indicating economic loss (profit) to the host country (acquirer, target, or both). In fact, the economic loss will be higher if the acquirer or target firm is associated with a developed country. However, a few limitations need to be checked before testing this theory in future research (refer to Reddy et al., 2014a:61–62).

5.1. Building testable propositions

We suggest testable propositions for further research in the cross-border M&A stream of emerging markets, which will advance the current knowledge on foreign acquisitions when researchers empirically test a large sample. The constructs are being developed on the basis of the research argument that overseas inbound investment deals in the form of acquisitions or mergers are delayed, and then become successes or failures for two important reasons that reflect the responsibility of the host country: (i) erratic behaviour of the sovereign (government officials, ruling political party) and (ii) weak institutional laws related to financial markets and taxation. Following this streak, the proposed theory posits that the acquirer or target firm enjoys economic benefits whilst the host country government experiences an economic loss resulting from supposedly lawful revenue.

On the basis of the understanding and research experience, we seek to present a weak regulatory system, along with evidence of the responsibility of international organizations, including the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, The Heritage Foundation, and Transparency International, to cite a few. In this vein, Lucas (1990) also postulated that developing countries characterize a poor economy and do not have sound institutional laws related to investor protection, intellectual property rights, ownership patterns, listing procedures, and so forth of legal, administrative, and policy implementation issues. In addition, some scholars argued that developing economies (so-called emerging markets) do not have sophisticated laws for anti-corruption, crime, social welfare, judgement delivery, and others. Several economic and law scholars suggested that corruption is one of the major economic barriers that adversely affects the economic development of a country, reflecting actions such as wasteful government spending and discouraging foreign inward investments (Tanzi and Davoodi, 1998).

According to the Transparency International-CPI report-2011, Russia was the most corrupt country (2.4) among the BRIC group, followed by India (3.1), China (3.6), and Brazil (3.8). In particular, the degree of corruption in India has declined in terms of CPI, from 2.7 in 2001 to 3.1 in 2011. The World Economic Forum (WEF) defined financial development in its Financial Development Report (WEF-FDR, 2012) ‘as the factors, policies, and institutions that lead to effective financial intermediation and markets, as well as deep and broad access to capital and financial services’ (p. xiii). Financial development is measured using factors such as size, depth, access, and the efficiency and stability of a financial system, which includes its markets, intermediaries, range of assets, institutions, and regulations (p. 4). The report was developed on the seven pillars of institutional environment, business environment, financial stability, banking financial services, non-banking financial services, financial markets, and financial access. In this paper, the institutional environment refers to financial sector liberalization, corporate governance, legal and regulatory issues, and contract enforcement. The rank for India based on the Financial Development Index was 40 in 2012, up from 36 in 2011. The change in rank for other BRIC economies was Brazil (32 from 30), China (23 from 19), and Russia (39). These results indicate that a lower rank infers more development. For example, Hong Kong secured the first rank, followed by the United States, the United Kingdom, and so forth. In terms of institutional environment, India placed 56 compared with Brazil (46), China (35), and Russia (59). In particular, the Heritage Foundation (THF) publishes the Index of Economic Freedom, which included a sample of 184 countries for its 2012 report (THF and WSJ, 2012). The objective of the index is ‘to evaluate the rule of law, the intrusiveness of government, regulatory efficiency, and the openness of markets’. The grades and ranks are usually based on 10 pillars of freedom, such as Property Rights, Freedom from Corruption, Fiscal Freedom, Government Spending, Business Freedom, Labour Freedom, Monetary Freedom, Trade Freedom, Investment Freedom, and Financial Freedom. India was ranked 123, Brazil 99, China 138, and Russia 144.

An official reference of the Doing Business 2012/2013 Report, a co-publication of The World Bank and the International Finance Corporation, presented quantitative indicators on the business environment and regulations for 185 countries (The World Bank and IFC, 2012 and The World Bank and IFC, 2013). The report computes an index value on the basis of 11 topics, such as starting a business, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property, getting credit, protecting investors, paying taxes, trading across borders, enforcing contracts, resolving insolvency, and employing workers. The given economy, India, was found to be in the lower middle-income category and its rank for ease of doing business fairly improved by seven points, from 139 in 2011 to 132 in 2012 and 2013. Brazil went from 126 to 130, China remained at 91, and Russia went from 120 to 112. Other indicators for India during 2012–2013 are as follows: starting a business (166–173), dealing with construction permits (181–182), obtaining electricity (98–105), registering property (97–94), obtaining credit (40–23), protecting investors (46–49), paying taxes (147–152), trading across borders (109–127), enforcing contracts (182–184), and resolving insolvency (128–116). For instance, to enforce a contract, one should wait at least 1420 days in India compared with Brazil at 731 days, China at 406 days, and Russia at 281 days, decreasing to 270 days and obtaining approval from 46 departments (procedures). Further, India ranked 166–173 for starting a business, relative to Brazil (120–121), China (151), and Russia (111–101).

The World Economic Forum also publishes the Global Competitiveness Report every year, in which it defined competitiveness as the set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine a country’s productivity level. The Global Competitiveness Index (GCI) is computed on the basis of 12 pillars of competitiveness: institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication, and innovation. For the 2013–14 Global Competitiveness Report (WEF-GCR, 2013), India was found to be one of the 38 factor-driven economies in that group (the other two groups were efficiency-driven and innovation-driven). In a sample of 148 countries, India ranked 60 for competitiveness, whereas Brazil was 56, China was 29, and Russia was 64. In the case of institutions, macroeconomic environment, and financial market development, India ranked 72, 110, and 19 compared with Brazil at 80, 75, and 50, China at 47, 10, and 54, and Russia at 121, 19, and 121.

These indicators suggest that India fairly improved its economic performance but was seriously affected by a weak institutional framework, including higher levels of corruption and political intervention. Therefore, the major theoretical foundation is that ‘in a given period, when a country’s regulatory system fails to improve in line with a similar group of countries, or fails to amend specific rules and guidelines for a public good, and when a system is highly corrupted by the known political instability and bureaucrats inefficiency, together leads to delay or break both public and business-purpose legal procedures – is described as weak regulatory system’; and this institutional dichotomy attribute adversely affects government fiscal income whilst benefitting other stakeholders (as mentioned in Reddy et al., 2014a:62).

Herewith, the propositions are redefined as follows. Firstly, we derive a few insights into the behaviour of the ruling political party and ministries in service during the announcement of cross-border inbound acquisitions. The service ministries and ruling political party officials interfered in two out of the three cases (Bharti Airtel–MTN and Vedanta–Cairn India). These entities were also noted as typically interfering if an overseas inbound acquisition is characterized by a high bid value and cash payment. In fact, the intervention is stronger if a deal has a higher valuation, cash payment, an acquiring firm from a developed country, and is in an industry largely accounted for by government-owned companies. Of central note is that many industries in India are controlled by public-sector undertakings, such as oil, gas, petroleum, power, railways, telecommunications, and so forth. Further, ownership in public and private limited companies is primarily held by family members. We find that the Bharti Airtel–MTN deal was valued at approximately US$23 billion and the Vedanta–Cairn India deal was valued at approximately US$8.67 billion. While supporting the politicking attribute, the Chairman of Bharti Airtel and top-level managers of MTN entered into negotiations with ruling political party officials, the telecom ministry, and other bureaucratic administrators. The Chairman of Vedanta Resources also met officials who have control over government approval issues related to the Cairn India deal. The common finding is that all three deals were larger in terms of deal value, which influenced the ruling party politicians to seek self-benefit (e.g. corruption). Given this consistency, we put forward a proposition for encouraging research on the market for overseas investments and acquisitions around the political uncertainty related to the host country’s domestic elections.

Proposition 1.1.

The host country’s ruling political party and respected service ministries interfere in foreign inward acquisitions or investments that characterize a high bid value and a cash payment.

Proposition 1.2.

The host country’s ruling political party’s and respected service ministries’ intervention is ‘more active’ in foreign inward acquisitions or investments flowing from developed countries and that are characterized by a high bid value and a cash payment.

Proposition 1.3.

The host country’s ruling political party’s and respected service ministries’ intervention is ‘more active’ in foreign inward acquisitions or investments characterized by a high bid value if that industry is largely controlled by government-owned or public-sector enterprises.

In addition to the interference by the ruling political party and respected service ministries, the behaviour of a given host country’s government officials and respected service institutions also influences the completion of the deal. In any country, the common practice is for government officials (e.g. department of revenue, central board of direct taxes) and regulatory authorities to receive applications regarding overseas investments; therefore, they are responsible for inspecting and approving such proposals. Interestingly, the erratic behaviour of regulatory agencies and governmental officials was injected into all three deals. For example, the Vodafone–Hutchison deal was litigated for approximately five years, after which Vodafone finally won the tax plea case in the apex court. Conversely, the Vedanta–Cairn India deal was delayed because of the open offers programme under the SEBI‘s takeover code and Cairn Energy’s production sharing contract with the public-sector undertaking of ONGC (of course, royalty payments). The deal was finally completed 16 months after the announcement of the acquisition. Further, institutional officers intermittently interfere in overseas inward acquisitions featuring higher bid values and cash payments. This interference is stronger if an acquirer belongs to a developed country and the industry is primarily controlled by public-sector undertakings. Following this, we develop a proposition to initiate new research on institutional distance (e.g. working culture among government departments) around overseas acquisition announcements.

Proposition 2.1.

The host country’s government officials and respected service institutions show erratic behaviour in foreign inward acquisitions or investments that are characterized by high bid value and cash payments.

Proposition 2.2.

The host country’s government officials and respected service institutions’ erratic behaviour is ‘more’ in foreign inward acquisitions or investments flowing from developed countries that are characterized by high bid value and cash payments.

Proposition 2.3.

The host country’s government officials and respected service institutions’ erratic behaviour will be ‘more’ in foreign inward acquisitions or investments characterized by a high bid value if that industry is largely controlled by government-owned or public-sector enterprises.

Using these constructs, we argue that border-crossing inward deals usually take more time compared with the actual time required to obtain government approvals. In other words, deals featuring higher valuations are delayed because of improper laws (e.g. cross-listing, open offers, ownership rights, investor protection, accounting standards). In effect, the inconsistent behaviour of government officials affects such deals. In some instances, such deals need more time to obtain sovereign approval when the investment is from a developed country. This situation is true in this case research. For instance, Bharti Airtel and MTN Group could have created a consolidated entity if the Indian government has a legal update on dual listings or cross listings. Realistically, no government wants to lose its control on any business or trade. Hence, the Indian government deregulated many industrial policies and, thereby, disinvested a significant number of public sector undertakings. For example, Vedanta acquired full control of Bharat Aluminium Company Limited, which was a loss-making unit that turned into a profit-making unit after a few years of integration. In this vein, we notice an interesting finding – an overseas deal characterized by a higher bid value and cash payments is delayed if that business is largely proclaimed by government enterprises. However, such deals require more time when an acquirer comes from a developed country. Further, the Vodafone–Hutchison and Vedanta–Cairn India deals (including legal issues) were severely delayed, and then became successes because both acquiring firms were registered in the United Kingdom, the advanced country. As such, Vodafone–Hutchison was one of the worst time-delayed cross-country deals in the world economy. The deal was initiated in December 2006, announced to the media in February 2007, and completed in May 2007. Tax authorities filed a petition in the given country’s state jurisdiction […] and, finally, the Supreme Court of India provided a judgement in January 2012. In sum, for Vodafone, the transaction consumed approximately 62 months. In contrast, Bharti Airtel wanted to merge with South African-based MTN Group. The deal was delayed and then cancelled during two rounds of negotiations (2008–2009) because of regulatory hurdles that were largely controlled by the SEBI and the Ministry of Finance. For instance, the hurdles refer to dual listing norms and complex deal structures involving open offers. The reality of the case is as follows: ‘the given country’s regulatory system does not define what a dual listing is’. With such insightful evidence, we suggest a set of constructs to investigate ‘deal announcement to deal completion (number of days)’ between domestic and overseas acquisitions in developed and developing nations.

Proposition 3.1.

Cross-border inward acquisitions (time required to obtain approval from the government) become delayed, and then are completed or broken because of weak institutional laws related to investor protection, cross-listings and intellectual property rights, and institutional officials’ erratic behaviour, if such deals are characterized by higher valuations.

Proposition 3.2.

Cross-border inward acquisitions require more time to obtain approvals from necessary government departments, causing delays in such deals. If such deals are characterized by high bid value and the investment is from a developed country, the they are completed or broken because of weak institutional laws related to investor protection, cross-listings and intellectual property rights, and institutional officials’ erratic behaviour.

Proposition 3.3.

Cross-border inward acquisitions characterized by higher bid values and that are in an industry largely controlled by government-owned firms (time required to obtain approval from the government) become delayed, and then are completed or broken because of weak institutional laws related to investor protection, cross-listings and intellectual property rights, and institutional officials’ erratic behaviour.

Proposition 3.4.

Cross-border inward acquisitions characterized by a high bid value, an investment from a developed country, and in an industry largely controlled by government-owned enterprises require more time to obtain approvals from necessary government departments, causing delays in such deals, which are then completed or broken because of weak institutional laws related to investor protection, cross-listings and intellectual property rights, and institutional officials’ erratic behaviour.

Following the previous argument, we explain the behaviour of acquisition costs attributable to delays in deals being completed or that are unsuccessful. Acquiring a publicly listed firm results in higher acquisition costs than when acquiring a privately held firm. Indeed, acquiring a firm in a foreign country also results in significant higher costs (e.g. border taxes, legal fee, registration fee, advisory fee, corporate gains taxes) compared with the costs involved in domestic deals. From a practical sense, the acquiring firm is responsible for bearing a significant portion of the acquisition costs that range between 2% and 5% of the deal value. Of course, this cost is directly associated with the deal completion process related to the time required to obtain government approval. In other words, the acquiring firm must bear all transaction costs until it obtains approval from government authorities, such as the high court, the relevant ministry (e.g. telecom), and regulatory bodies (e.g. SEBI, CCI). Therefore, acquisition costs increase when a deal is delayed or unsuccessful because of the weak laws related to securities markets and investor protection, and the inconsistent behaviour of sovereign departments, assuming higher valuations and cash payments. In some instances, acquiring firms must allocate more funds for acquisitions when an investment is from a developed country and the industry is largely controlled by government firms. Although we support this streak, we acknowledge that Vodafone incurred significant costs, such as communication costs, legal proceedings costs, and other associated costs, during 2007–2012 because of the delay in receiving a judgement. Conversely, both Bharti Airtel and MTN Group spent significant funds during two innings; however, such expenses had to be recorded as ‘sunk costs’ given the unsuccessful negotiations. Therefore, we recommend a proposition for initiating further investigation into transaction costs around delayed, successful, and incomplete deals between domestic and overseas entities.

Proposition 4.1.

If deals are characterized by high bid values, acquiring firms’ acquisition costs increase in proportion to the deal completion process (time required to obtain government approvals) given weak institutional laws related to investor protection, cross-listings, intellectual property rights, and institutional officials’ erratic behaviour.

Proposition 4.2.

Acquiring firms’ acquisition costs are ‘more’ (more than the proportion of the deal completion process) given weak institutional laws related to investor protection, cross-listings, intellectual property rights, and institutional officials’ erratic behaviour, if the deals are characterized by high bid values, investments are from developed countries, and the industry is largely controlled by public sector enterprises.

Finally, we reach the focal point – how do unsuccessful deals affect the given host country’s revenue or income? Extant studies suggested that an international direct investment from a developed economy largely benefits the host country’s economy in terms of incentives such as new capital creation, industrial development, new job creation, the supply of goods, better utilization of resources, enhanced skills and expertise, transfer of technology and revenue to the sovereign, and so forth. At the same time, such an investment adversely affects market conditions, the pricing of goods and services, competition, the survival of local firms, and other uncertainties. On the basis of multiple case research, we argue that a country that invites foreign investment (FDI or the acquisition route) loses economic benefits such as taxes on revenues, border taxes, capital gains taxes on cash deals, and non-economic benefits including technology transfers when the number of incomplete deals or withdrawals increases because of weak institutional laws, politicking, and the irrational behaviour of government officials. In other words, an increase in the number of incomplete deals adversely affects the fiscal revenue of the country inviting foreign investments. Furthermore, the economic loss is high if an acquisition is characterized by a higher valuation, cash payment, an acquirer from a developed nation, and an industry that is largely directed by state-owned enterprises. Vodafone benefitted from avoiding a capital gains tax through a landmark judgement by India’s apex court, which stated that existing tax guidelines do not allow tax authorities to impose capital gains taxes on Vodafone in the Vodafone–Hutchison deal. As a result, Vodafone benefited by approximately 20% of the given deal amount (US$10.9 billion), or US$2.18 billion. By and large, Hutchison-Whampoa Limited (HWL) also benefited from the premium value that Vodafone paid. In reality, HWL had invested approximately US$2.6 billion in India since 1995 and sold to Vodafone for US$10.9 billion, for a benefit of US$8.3 billion, per se. In the paradigm of international laws, only an acquiring firm is liable for paying taxes and not the target firm. In sum, both acquirer and target benefited because of loopholes in the given country’s institutional setting. In contrast, the sovereign might have lost fiscal revenue in the form of corporate taxes, listing fees, cross-listing fees, and border taxes because of the unsuccessful Bharti Airtel–MTN Group transaction. Both cases were found to be true given weak laws related to securities markets, investor protection, and border taxes. In addition to losing capital inflows into India, capital flowed outward when Bharti Airtel acquired Kuwait-based Zain Telecom [after breakup talks with MTN]. Given these constructive arguments, we recommend a proposition for improving the current knowledge on ‘nationalism and institutional dichotomy’ in cross-border inbound investments.

Proposition 5.1.

A country’s sovereign expected revenue declines in proportion to an increase in the number of unsuccessful international deals.

Proposition 5.2.

A country’s sovereign expected revenue declines ‘more’ than the proportional increase in the number of unsuccessful international deals, if such deals are characterized by high bid value, cash payment, an investment flowing from developed countries, and an industry largely controlled by public-sector enterprises.

Proposition 5.3.

The acquirer and/or target firm benefits (e.g. from undervaluation of domestic firms, capital gains taxes on cash acquisitions) in cross-border inbound acquisitions because of a host country’s weak financial markets and tax regulatory environment.

In addition, this construct is strengthened if future scholars undertake the composite proposition put forwarded by Reis et al. (2013): ‘A greater difference between acquirer and target nations’ (i) economic institutions; (ii) political distance; and (iii) social institutions ‘(a) reduces the likelihood of completing an announced M&A deal and (b) lengthens the period from announcement to completion/withdrawal of the M&A deal’.

Lastly, we propose that developed country-based firms, such as Vodafone, Vedanta, and Cairn Energy, acquired good knowledge on the given country’s constitutional system, weaknesses in the regulatory setting, tactics for approaching public administration authorities and bureaucrats, relations among politicians, bureaucrats, industry associations, jurisdictions, media, and the public, and the market potential for its survival. Thus, acquiring a firm in a developing country such as India is a learning experience for developed country MNCs when engaging in future deals in that country or other nations. Researchers in IB, strategy, finance, accounting, and economics are advised to test these theoretical propositions, which advance the understanding of the theory.