Publications ‘Protectionism’ In M&A: A Mixed Picture

- Publications

‘Protectionism’ In M&A: A Mixed Picture

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

Background

When a national ‘champion’ is at stake, lively political and media debate often follows, sometimes even where the sector involved is not particularly ‘sensitive’. This is unsurprising in markets facing slow economic growth and, more recently, there has been an interesting interplay between expanding sanctions regimes and policy in this area. But just how often is the national ‘champion’ card played such that cross-border M&A deals are blocked or hampered?

With cross-border M&A deals last year having been at their highest levels since the financial crisis, we look at some recent market trends and developments on ‘protectionism’, as well as some practical considerations. In particular, we focus on those relevant to investing in Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Russia, the UK and the U.S.

What?

While ‘protectionism’ can come in many guises, in this publication we focus on foreign investment restrictions, antitrust regimes and takeover rules which can be used as levers for states or regulators to block or influence the outcome of a deal.

The policies and objectives underpinning these various rules are often quite different and can give rise to unexpected results. Notably, foreign investment restrictions can lack clear scope and this can make it difficult to predict whether a deal is likely to be blocked or require modification. And, in some cases, approval processes and delays can also be significant concerns for investors.

For example, so far, China has not formally used its national security rules adopted in 2011 to stop a foreign company from acquiring control of assets or companies controlled by Chinese entities (these were adopted in what was generally seen as a tit-for-tat response to the 2010 prohibition by U.S. authorities of Huawei’s acquisition of 3 Leaf on alleged U.S. national security grounds). Overall, in fact, restrictions on inbound and outbound investments are being relaxed. But instead, Chinese authorities have flexed their antitrust rules and have applied them very broadly in ways which have been viewed as protecting local industry, particularly, where intellectual property and consumer goods are concerned (see below).

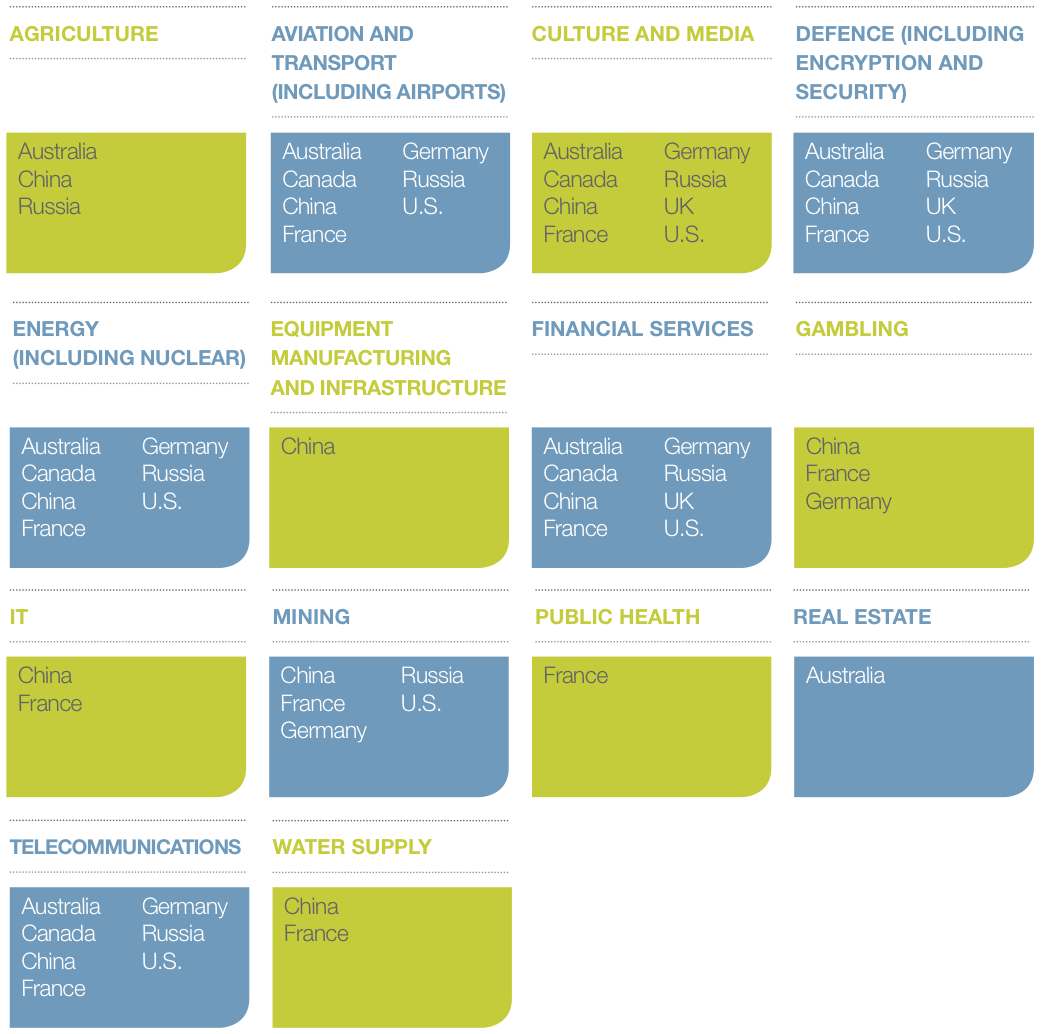

When considering a transaction in certain countries, additional sector-specific rules may apply. The ‘protectionist’ features of these rules vary depending on the country and include foreign ownership limits or increased scrutiny of the proposal as part of the ordinary foreign investment approval process and outright prohibitions on the acquisition.

Recent market trends and developments

When it comes to identifying market trends and sectors that are likely to attract more scrutiny, the picture varies quite considerably both on a national and global level. A state’s policy on foreign investment at any particular point in time will inevitably be influenced by external drivers, such as economic and geo-political factors.

FRANCE

A good example is France, which has adopted a number of recent ‘protectionist’ measures in the wake of an economic slowdown.

It has expanded its controls of foreign investments to energy supply, water supply, transport networks, electronic communication services and public health. This was done at a time when the French government was openly opposed to the proposed acquisition by U.S. conglomerate General Electric of Alstom’s electricity generation assets and indirectly solicited Siemens, a German company, to make a competing offer for Alstom’s assets.

The deal completed with a number of commitments being given by General Electric to France. Bouygues, the main shareholder in Alstom, immediately allowed France to exercise 20% of Alstom’s voting rights through securities lending arrangements and supported France’s appointment of two directors. In parallel, France entered into an agreement with Bouygues giving it certain other rights over part of the Bouygues stake lent to it. These include the right to acquire this stake progressively through several options. On the back of this transaction and of the sale by Vivendi of SFR to Numericable, a company controlled by a Swiss resident, the Autorité des marchés financiers is proposing that rules should be introduced requiring a French listed company to seek shareholder approval for sales of major assets.

Other rules have also been brought in which give a French listed company more protection against a hostile bid (and other steps by a bidder to take de facto control). The introduction of a wide range of measures last year which bypassed usual parliamentary procedures and included those which: require a minimum acceptance threshold of 50%+1 to be included in a public bid; allow a French company to defend a hostile bid by taking frustrating action without shareholder approval; provide more information and consultation rights for targets’ works councils before the launch of a bid; and, controversially, provide automatic double voting rights for longer-term shareholders was seen by many as a sudden injection of economic patriotism into French takeover rules.

RUSSIA

Economic and geo-political factors are continuing to have an important impact on M&A deal execution in Russia. While very few M&A transactions have been formally blocked over the years – most major transactions tend to be cleared before execution – there has been a recent trend for increased ‘protectionism’ in certain sectors, such as media and telecommunications (eg with the lowering of the foreign ownership threshold from 50% to 20% for all mass media and broadcasters from next year onwards).

Other steps which have been taken by the Russian government more generally, and which are viewed as a direct reaction to tensions with western countries, include rule changes requiring personal data of Russian citizens to be processed by servers within Russia and those which require international payment cards to be processed locally.

In contrast, other sectors in Russia have been opened up, such as oil and gas, again as a response to tensions with western countries (and, in particular, EU and U.S. sanctions) but here with the aim of attracting foreign investment to support the economy. Rules have been amended recently to increase the ceiling for an individual foreign state to acquire a stake in a Russian subsoil strategic company from 10% to 25%. And, while previously a hard line was often taken in relation to approvals of sales of major subsoil assets to foreign investors (and, in particular, investors controlled by foreign states), this has softened and has led to a number of cross-border M&A transactions being recently announced, including the proposed sale by Rosneft Oil Company of a minority interest in one of its major upstream assets, Vankorneft, to China’s CNPC in late 2014.

However, this should be put in context. Investment levels in Russia have been decreasing despite government moves to attract foreign investment, which include plans to privatise a number of state-controlled champions in the medium term and the establishment of the Russian Direct investment Fund, which can only co-invest with foreign investors. There are various reasons for this, including the fact that U.S. and EU sanctions targeting Russia have placed a number of restrictions on western companies’ ability to finance and invest in Russia and Eastern Ukraine, particularly in the oil and gas sector. The court ruling in late 2014 to nationalise, in effect, a domestic company’s substantial stake in the large Russian oil company, Bashneft, is contributing to market uncertainty.

Other countries where the picture is mixed and very much depends on the sector involved include Australia, Canada, China and the U.S.

AUSTRALIA

In Australia, there appears to be a two-fold approach towards ‘protectionism’. On the one hand, there seems to be an overall trend for decreasing ‘protectionism’ so long as there is a corresponding potential upside for the Australian economy. For example, in recent years, the Australian government has taken a number of positive steps to attract foreign investment, including entry into bilateral trade agreements with Japan, Chile and South Korea. An equivalent agreement with China is also expected to be signed this year. These agreements, together with existing bilateral agreements with the U.S. and New Zealand, smooth the way for deals involving non-government investors from those countries by raising deal notification thresholds (other than in sensitive sectors).

Another indicator of a trend for decreasing ‘protectionism’ is that only a very small number of transactions have been blocked outright under foreign investment restrictions. This is good news for foreign investors, particularly given the expected spate of privatisations, for example, in the infrastructure and utility spaces.

On the other hand, areas that have drawn particular public and governmental scrutiny lately, and that are earmarked for more stringent measures, are agricultural land, agribusiness and residential real estate.

Recently, a lower approval threshold was introduced for proposed transactions by foreign investors in agricultural land and the government has also announced plans to introduce a foreign ownership register for agricultural land. Separately, a consultation process is underway to introduce a new screening threshold for foreign investment in agribusiness, new foreign investment application fees and substantial fines for breach of the residential real estate foreign investment regime.

CANADA

State-owned entities (SOEs) investing in Canada can expect to see closer scrutiny of their investments in the future. The government will take into account additional factors when deciding whether reviewable acquisitions of control are of net benefit to Canada, including the governance and commercial orientation of the SOE in question. More particularly, a special restriction was put in place a few years ago in relation to Canadian oil sands businesses when, on the back of two SOE acquisitions in this space, the government said that, in future, similar acquisitions would only satisfy the net benefit test in exceptional circumstances.

Another recent contrasting trend has been in the context of the Canadian book publishing sector where there seems to have been a relaxation of strict enforcement of investment restrictions (eg U.S. company HarperCollins Publishers’ acquisition of Torstar Corporation’s Harlequin book publishing and distribution business in 2014).

CHINA

Meanwhile, in China, the overall trend is a loosening of restrictions on inbound and outbound investments. But, some specific sectors such as IP-heavy sectors and/or consumer goods (including telecommunications devices, food and automobiles) are closely guarded. For example, the Ministry of Commerce People’s Republic of China (MOFCOM) conditionally cleared U.S. company Microsoft’s acquisition of Finland’s Nokia’s devices and services business in 2014 and imposed restrictive conditions on both parties in terms of their intellectual property rights. In airing its concerns, it became clear that what MOFCOM was primarily interested in was protecting China’s smartphone industry rather than protecting its users.

The recent decision by China to drop leading foreign technology brands from its approved state purchase lists should be assessed in the same context. And recently China imposed substantial fines on U.S. company Qualcomm and introduced strict pricing limitations for abusive patent licensing practices, creating doubts about the level of legal protection enjoyed by companies already operating in China. More scrutiny is expected in future in these IP-heavy and/or consumer goods sectors.

U.S.

Intervention by the U.S. government to prevent or mitigate foreign investment in the U.S. has generally been limited to national security grounds. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) reviews transactions which could result in control of a U.S. business by a foreign person to determine their effect on national security and which have either been voluntarily notified to it by parties or in respect of which it has launched its own investigation.

Between 2009 and 2013, CFIUS launched an investigation in respect of approximately 40% of transactions which sought CFIUS approval: this represents a significant uptick in the number of investigations by the Obama administration as compared to the last administration. An example of this is when a U.S. company owned by two Chinese nationals, Ralls Corporation, was ordered in 2012 by President Obama to divest four wind farm projects in Oregon because the wind farm sites were too close to a U.S. navy restricted airspace and bombing zone. This was the first Presidential Order to divest in more than 20 years and, although Ralls challenged the Order in a lawsuit, it ultimately divested the foreign ownership of the wind farm projects. Another example which attracted substantial media coverage, albeit some time ago in 2006, involved the state-owned Dubai Ports World’s planned acquisition of P&O, a UK group. While originally approved by President Bush, Congress expressed strong opposition and Dubai Ports bowed to the pressure and withdrew.

A complete divestiture or abandonment of a proposed merger by the foreign investor may not always be required. Mitigation tools may be used to limit or restrict the foreign involvement to allow the transaction to proceed. For example, in 2006, during negotiations with the U.S. government on the Alcatel-Lucent merger, the companies agreed to create an independent U.S. subsidiary, run by U.S. nationals, to handle sensitive government contracts with a special board of independent directors with military or defence experience. The agreement contained provisions to separate certain employees, operations and facilities, as well as restrictions on control by the parent company and on the flow of certain information. Notably, the agreement contained a condition providing the U.S. government with an ongoing right to reopen and unwind or alter the merger if it believes the terms of the mitigation agreements are not being met.

GERMANY

In Germany, investment has been largely welcomed, with foreign investment restrictions only being invoked in very limited circumstances.

UK

Similarly, in the UK, there have been very few cases of active ‘protectionism’. And where the government has stepped in on merger control public interest grounds, this has tended to be due to public security concerns. But this has not stopped other public scrutiny (largely in the form of the media and political debates) of some high-profile bids by overseas bidders for national ‘champions’, some of which has prompted recent regulatory changes and has rekindled the debate about whether a broad public interest test should be reintroduced as the test for assessing UK mergers.

Following U.S. company Kraft’s bid for Cadbury in 2010, rules were introduced to give more power to targets to defend hostile bids, such as rules which limit the period under which a target can be subject to siege from a possible bidder, but some of the more controversial measures debated by politicians, such as raising the approval thresholds for securing change of ownership, requiring bidder shareholder approval on all takeovers and disenfranchising short-term shareholders, were parked. The possible bid by U.S. company Pfizer for AstraZeneca in 2014, also saw a fresh debate taking place around whether the grounds on which the government can intervene under merger control rules should be expanded to include, in this case, protection of R&D and technology.

Independently, new UK takeover rules were introduced to give the regulator enhanced powers to monitor and enforce commitments made by parties either to take or not to take certain action after the end of an offer. This was prompted by commitments made by Pfizer in relation to AstraZeneca regarding, for example, the decision to base key personnel in the UK.

What does this mean in practice?

While ‘protectionist’ tendencies have been increasing in some countries, and/or in particular sectors, and they remain an important consideration in these contexts, the overall proportion of cross-border M&A deals that are blocked or hampered as a result is, in practice, relatively small.

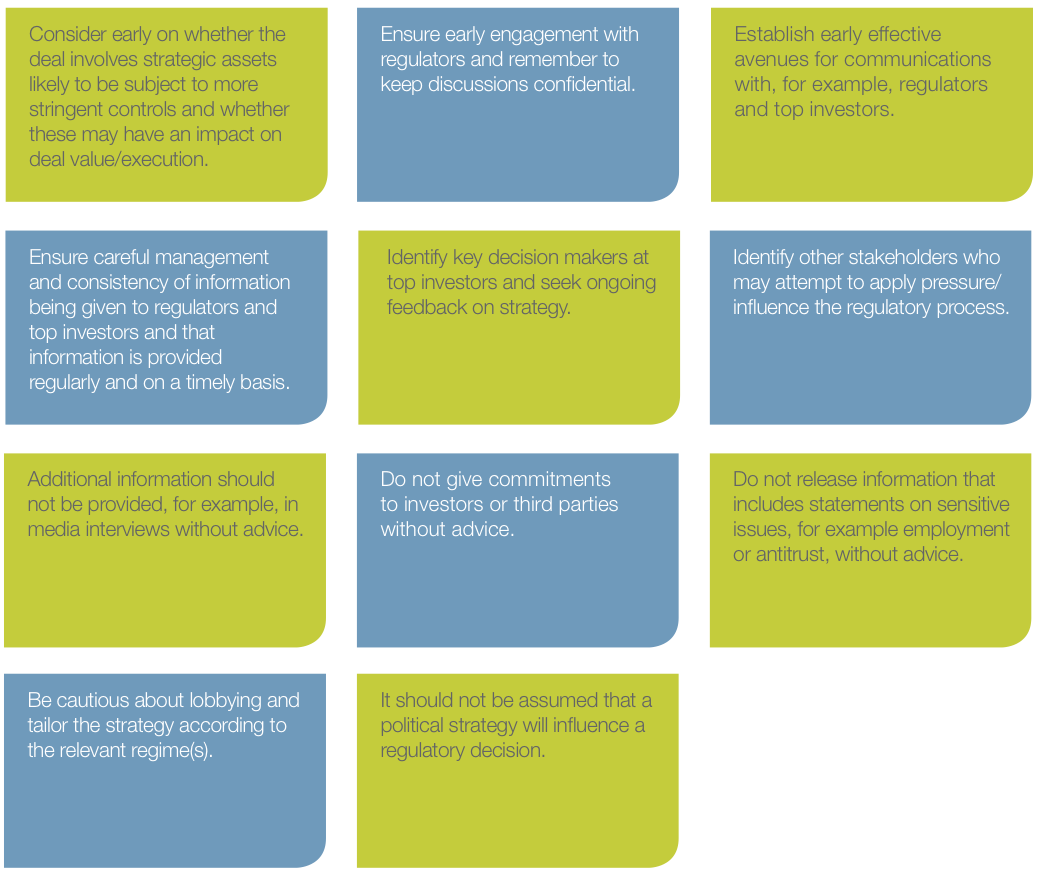

Some practical considerations

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter