Publications Post Merger Integration: Hard Data, Hard Truths

- Publications

Post Merger Integration: Hard Data, Hard Truths

- Bea

SHARE:

By Johannes Gerds and Freddy Strottmann with Pakshalika Jayaprakash – Deloitte

The numbers don’t lie. Many top corporate managers are faced with the challenge of a post merger integration (PMI) at least once in their career. And empirical studies indicate that one of every two PMI efforts fares poorly. These statistics are particularly telling given that mergers and acquisitions have been a staple management instrument for almost a century now and that there has been growing professionalism in corporate M&A efforts over the last decade: practically every transaction is accompanied by due diligence, with the increased involvement of external specialists such as lawyers, auditors, tax consultants and investment bankers. Yet challenges with post merger integration are consistently high and the resultant threat to a company’s performance perhaps higher than it needs to be.

There are no hard and fast rules to ensure that a given merger will result in corporate wedded bliss. But we have found that quantitative analysis — something PMI managers have largely overlooked — can evoke both surprising questions and even more revelatory answers. Certain post merger integration scenarios, which we describe below, can create very difficult starting points for the companies and the managers involved. If a company faces one of the less favorable scenarios, it becomes doubly important to assess the likely causes of difficulty and to address these proactively and thoroughly.

In an empirical examination of one of the world’s largest PMI databases by the authors and the University of Muenster in Germany, a set of risk factors have emerged that are statistically significant — as opposed to just hearsay — in influencing PMI success, as defined by criteria described below. These factors also can be used to help determine the types of “risk profiles” that pertain to a merger, each profile having a unique statistical likelihood even before any integration measures have been implemented. Identifying the risk profiles before closing a deal is thus crucial.

Extrapolating from our quantitative analysis, certain PMI myths emerged that can influence both the effectiveness of the PMI process and the comparative difficulty in realizing the value of the merger – proposed or imminent. Using statistical analysis in an effort to minimize risks and discard outdated notions can help an organization stack their odds in favor of a more successful post merger integration.

Hard data, hard truths

The literature on merger successes is voluminous but for the most part anecdotal. No doubt these lessons learned can be helpful in minimizing mistakes and improving execution. Where they fall short, however, is in failing to make use of the quantity of data available from a vast collective experience in post merger integration. Simply put, we have witnessed a lot of good and bad merger aftermaths and know it is possible to approach the next one armed with a quantitative understanding of the risks involved.

We have conducted a comprehensive empirical analysis, based on an evaluation of one of the world’s largest PMI databases, built up over a period of six years by the authors in a joint research effort with the University of Muenster, a leading university in Germany. Containing more than 45,000 data points from post merger transactions in all important sectors worldwide, the database uses a representative global sample—from Europe (61 percent), Americas (28 percent) and the Asia Pacific region (11 percent)—of all key industries: services and manufacturing, comprising both large enterprises and mid-sized companies.

How can we quantify merger success? Many studies use capital market-based indicators. But doubts are emerging as to how to isolate the single effect of a post merger integration on share prices. How can we separate this specific effect from other influences – e.g. increased raw material prices or altered demand behavior? And even if a clear answer to the M&A success question could be provided on the basis of share prices, how can the effects that relate exclusively to the PMI (and not, for example, to pre-merger factors like an inflated purchase price) be filtered out of a share price–based statement of risk?

We began by defining PMI success based not on share prices but on the extent to which targets like cost synergies, cross selling or know-how transfer were met. But, for a true merger success, reaching these targets alone isn’t enough. Factors like implementation costs going over budget or key personnel leaving the company in droves may result in major delays, even as key targets are attained. We thus extended our definition of PMI success to include criteria such as implementation efficiency and social compatibility – seen in the company’s management systems, its underlying ideology, and in its relationship with employees (for example, employee participation, working hours, pay, health and social security benefits, etc.)

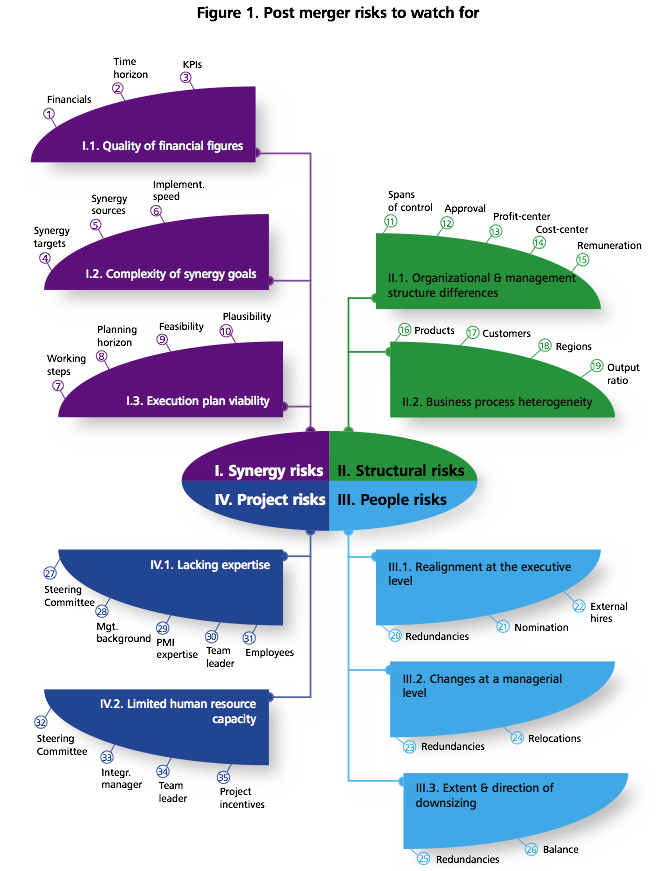

Our team examined over 300 factors discussed as potential risks. At its core, our research identified those factors that influence the post merger risk based on solid statistical criteria. When the number-crunching frenzy had ended, we found only 35 factors within four categories to be statistically significant in influencing PMI success. These ranged from skimpy financial figures to organizational and leadership friction to dearth of expertise (see figure 1).

We then statistically condensed these 35 factors into four categories of risks—synergy, structure, people and project—that can undermine the success of post merger integration. Synergy risks comprise all factors stemming from inadequate synergy realization planning, while structural risks arise from mismatched organizational structures and processes. People risks refer to factors based on personnel resistance. Project risks, the last category, involve project-related obstacles to post merger integration.

Drawing from these four categories of risks, it is possible to assess in advance the comparative difficulty of a specific post merger integration. Our analysis suggests that post merger integrations differ fundamentally in terms of risk profile as well as success potential, and that managers face very different post merger challenges.

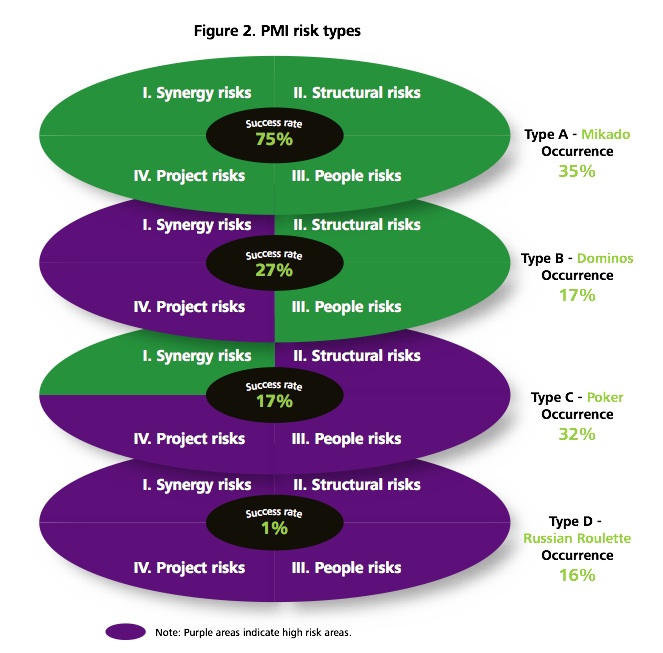

Faced with the challenge of a post merger integration, managers are confronted by one of four risk types, each derived from empirical analysis of our PMI database. Each is named with an allusion to the type of challenges it poses. Each is defined by the levels of risk in the four categories just described: synergy, structure, people and project. Going a step further, we can calculate how a particular merger is to be rated in each of these risk classes by assessing the underlying factors via benchmarking with our PMI database. This lends some structure to what can be an otherwise well-intended but unsubstantiated assessment.

First the good news: 35 percent of all PMIs evaluated were of the low-risk variety we call Mikado. Three times out of four, these PMIs ended well, in that they met our criteria for success. We saw no more than low to moderate levels of risk in any of the four risk classes (synergy, structure, people and project). The flat risk profile points to a high probability of success, but these kinds of transactions are by no means risk free. In the game Mikado (also known as “pick-up sticks”), the main challenge is mastering the skill to pick up one stick after another from the complex jumble of colored sticks without touching the rest of the pile. The larger the pile, the more intricate the challenge and the harder it is to keep track of things. As in the game, Mikado post merger activities were above all about having the right, delicate touch.

Less encouragingly, another one third or so of post merger managers we evaluated were forced into what we call thePoker variety of merger. In our study, these types of transactions had an 83 percent failure rate, in that they did not meet one or more of our criteria and posed very high post merger risks in three of the four risk classes: structure, people and project. The Poker-variety mergers were marked with a high degree of heterogeneity in both organizational and process structure. The need to recognize and assess different forms of staff resistance suggests a parallel to the card game, where success often depends on being able to realistically size up opponents’ hands and strategies by scrutinizing their card playing and betting habits. In terms of project risks, almost all Poker transactions evaluated were marked with insufficient human resource capabilities: they were understaffed and suffered from inadequate expertise from the acquiring company.

Mikado and Poker are the most common variations of PMI scenarios, occurring two-thirds of the time in our study. The remaining one-third of integration projects were distributed between the other two risk types: Dominos and Russian roulette.

Representing 17 percent of all PMI efforts we evaluated, Dominos mergers were symbolized by high synergy and project risks, with relatively minor threats stemming from structure. Also, especially compared to Poker, people risks were quite marginal for this merger type; there was likely no resistance from managers and employees. Because risk levels are significantly lower than Poker deals, management’s success rate with Dominos was considerably higher at 27 percent, yet still far from the 75 percent success rate for Mikado.

The riskiest type of PMI transaction, the Russian roulette, accounted for approximately 16 percent, or one in six, of PMI situations evaluated. Within Russian roulette, the following risk areas were more prevalent than in any of the other three merger types: low quality of financial figures, vast organizational and management differences, severe top management resistance and low execution plan viability. Fully 90 percent of efforts evaluated that fell into this risk type lacked a viable execution plan.

With dangers in all four risk classes, the Russian roulette mergers we evaluated failed 99 times out of 100 – a rate higher even than that of its namesake. It is important, therefore, to recognize the circumstances leading to this type more than any other and manage accordingly.

Defining the factors

Expressing these 35 factors with sufficient rigor required precise definitions. For example:

The quality of financial figures was defined as the number of previous fiscal years for which P&L statements and balance sheets were available for the pre-merger companies. In addition, we analyzed the type of metrics available in the standard management reporting (such as EBIT, Free Cash Flow or ROCE).

We operationalized execution plan viability by analyzing integration steps that were performed (e.g. actions taken to retain key personnel and / or in training), thus separating statistically top performing companies from average ones. Our research included the number of months covered by the integration plan and the number of people involved in the integration planning process from both the buyer and the target companies.

Organizational and management structural differences included measurable factors like span of control, managers’ remuneration schemes and the percentage of employees working in a profit center or cost center. As for business process heterogeneity, we measured this through the revenue split by customer segments, regions and product groups.

Changes at the managerial level included factors that are easily measurable such as scope of redundancies and the magnitude of relocations as a percentage of management positions.

We defined the integration manager’s experience—or lack of it—as the number of PMI projects that he or she had conducted in the past. At the steering committee level, we calculated the percentage of steering committee members that had previously conducted large scale organizational transformation projects.

Limited human resource capacity was also measured along the organization for the steering committee, integration manager, team leader and project teams. The major question we asked: What percentage of time did they dedicate to project work?

PMI myth versus PMI reality

Beyond enabling us to assess the overall factors impacting a successful post merger integration effort, the data point to some common misconceptions. With only 35 factors proving to be statistically significant, this suggests that more than 270 factors widely and often emotionally discussed in the business community—like merger-of-equals, size of target company, size of buyer, corporate mergers—don’t quantitatively nudge the pendulum toward success. What’s more, it suggests that prevailing wisdom and intuition have, for decades now, lured post merger management efforts down more than a few false avenues.

Myth 1: The faster, the better

Sixty percent of the managers we interviewed felt that the faster the integration process is implemented, the better the prospects of realizing synergies and ultimately of PMI success. Yet according to our analysis, this is untrue.

Our analysis indicates that the underlying factors driving synergy risks are mainly three: first, the poor quality of financial figures – common when buying start-ups or carve-outs, as figures to validate and project the operational performance are often unavailable due to missing operational history. Integration hazards also increase with the complexity of implementing synergy goals. For example, realizing tax advantages through a merger may be a less complex goal than realizing cross-selling synergies required to align the entire value chain from product portfolio, sales, marketing, supply chain, distribution, production and R&D. The third risk driver arises from inadequate implementation planning, which overlooks important integration steps such as employee training, alignment of incentives or IT systems, and involvement of line management sufficiently early in the process.

The margin for error, both in assessing synergies and in capturing them, can be slender to the point that even minute mistakes can wipe out projected economic benefits. But take your time and do it right and the results can be gratifying.

The margin for error, both in assessing synergies and in capturing them, can be slender to the point that even minute mistakes can wipe out projected economic benefits. But take your time and do it right and the results can be gratifying. We saw this in the merger of two global high tech companies where operational management from both sides were heavily involved in the integration planning process; the final tally stood at 1,500 managers, representing about one percent of the entire personnel. Due to the vast involvement of operational experts, realized synergies exceeded the target plans by more than $1 billion.

Myth 2: National mergers are less risky than cross-border mergers

Twenty eight percent of managers interviewed agreed with this view – yet statistics suggest otherwise.

Our analysis shows that PMI risks are driven not primarily by external factors like the nationality of the buyer or target but by internal structural risks. These risks fall into two broad categories: those arising from differences in the organizational and management structures and those with their origins in dissimilar business processes. Structural incompatibility can exist, for example, because of conflicting degrees of centralization in decision making. Differences in core processes, however, ultimately reflect the disparities in companies’ market and business requirements, perhaps as a consequence of divergent market orientations in products, customer groups and sales regions.

…fully 64 percent of managers interviewed believe that resistance tends to be low at the top management level and high at the worker level. But our findings show that post merger integration projects face resistance at all levels, from regular workers to middle and top management.

The union of two European engineering companies is a prime example of a merger that brought together companies with very different structures – a business unit of a much larger corporation and a stand alone company. The business unit had a more decentralized management approach with responsibilities delegated within functional areas such as procurement and IT. In contrast, the stand alone company had a more centralized approach with a strong corporate headquarters retaining control over IT, finance, procurement and HR. Bringing these two disparate structures together without reconciling these differences almost destroyed the new company. Sales plummeted and key people left, unable to adjust to the new corporate structure. Within three years the company collapsed, to be swiftly scooped up by a competitor.

Myth 3: Employee resistance is the largest integration barrier

There’s no doubt that people risks lie at the heart of many PMI failures, given the multiple, complex ways they can manifest. Yet these risks are misunderstood: fully 64 percent of managers interviewed believe that resistance tends to be low at the top management level and high at the worker level. But our findings show that post merger integration projects face resistance at all levels, from regular workers to middle and top management. Perhaps counterintuitively, resistance is especially high at the top management level. This is likely because personnel risks in terms of layoffs are more pronounced at the management level as the new company will probably shy away from retaining two marketing heads or two finance managers on the organization chart.

The magnitude of people risks is influenced by the extent of redundancies: the larger the proportion of layoffs and thus the danger of losing one’s job, the greater the hostility to a PMI. However, there are other factors amplifying people risks, such as the delayed selection of NewCo management or a larger-scale relocation of jobs requiring managers to travel extensively or even relocate. The unbalanced distribution of downsizing between the merged organizations intensifies the scope of employee-related risks; the emergence of a winner-loser mentality inevitably leads to resistance among staff who believe that their units drew the short straw when jobs were sacrificed.

Management issues get all the more murky when a corporation acquires a founder-led company that has conflicting management and organizational approaches. A deeply embedded culture or one that is idiosyncratic and personality-driven can result in power struggles that draw attention away from vital decisions concerning the integration. Then there’s the elephant-in-the-room question: What to do with the founder?

What are your PMI success chances?

The following questions can serve as a starting point for those contemplating integration in the wake of a merger. If your leadership team can answer all nine questions concerning your next PMI transaction, that bodes well. If there are gaps in your company’s responses, or some grey areas, then the prospects for a successful PMI may well be reduced. And an abundance of blanks on the answer sheet suggest that the risks may overwhelm a team’s strongest efforts. Your company’s best bet for success would lie in identifying and resolving these issues early in the post merger integration process.

1. Are the financial figures for the transaction sound?

• Are the NewCo’s planning timeframe and budget sufficient to actually complete the execution of essential integration measures (such as integrating the IT systems)?

• Does reporting promptly deliver the key figures required to continually measure PMI progress and success?

2. Have the synergy goals been mapped out in enough detail?

• How broad can the scope of change be in the individual business areas without overburdening the organization or endangering day-to-day business?

• In what areas are synergies targeted? How fast are the synergy targets to be realized?

3. Has the implementation concept a sufficient operational foundation?

• Does the integration concept embrace all the essential implementation steps such as employee training and harmonizing incentive systems and IT systems?

• Was line management of the acquiring company—and depending on the context, also of the target company—closely involved in the process of confirming synergies?

• Likewise, what operational risks did line management discuss when synergies were being evaluated (e.g. negative impact on current business)?

4. Do the corporate structures fit well together?

• Do the companies differ in terms of the span of control and degree of decision-making centralization?

• Does the decision-making leeway, in terms of profit and cost centers, differ between buyer and target?

• How dissimilar are the compensation and incentive structures (e.g., the variable portion of remuneration)?

5. Are core processes similar?

• To what extent do the companies diverge in terms of their product and market orientation? Where do they overlap?

• What differences exist in core activities such as market development, order processing, production of goods and services or extent of outsourcing?

6. Has a management concept been worked out?

• What criteria will be used to choose the new management team and when will names be announced? Which executive positions are expendable?

• Will the existing team be augmented by external managers (in order to foster restructuring efforts)?

• How can top performers at the target company be identified early on and their commitment to the new company secured? Which areas are likely to face particularly strong resistance from management?

7. Have the required staff-related measures been itemized?

• How are job cuts distributed between the buyer and target companies? What share of the reductions cannot be made in a “socially acceptable” fashion?

• How much financial room for maneuver is there to provide incentives for voluntary solutions? What additional schemes (e.g., outplacement center, applicant training) are feasible to help redundant employees in their job search?

8. Is adequate PMI expertise available?

• According to what criteria and processes are the integration project organizations staffed?

• Do these project members, especially those from the integration management team and steering committees, have enough experience with post merger integrations? And to what extent are their experiences gained from past integrations available (e.g., documented in handbooks)?

9. Is there enough human resource capacity on hand?

• How are ongoing projects prioritized in relation to the post merger integration? In what areas is there a dual burden (e.g. due to successive acquisitions)?

• Which PMI task forces need to be formed and staffed by higher-up managers (e.g. second- or third-rank management)?

Myth 4: Soft factors are more important than hard factors

Forty-six percent of the management interviewed share the opinion that soft factors like motivating people are more essential to merger success than hard factors like project management. Our analysis suggests that it is important to address both soft and hard factors. Even if a merger appears to pose little risk in terms of synergy, structure or people, project risks can still undermine a PMI. If a formal project organization to integrate the target company is not established, for example, there is a strong likelihood of exceeding the initial expected investment.

Post merger integration has long been treated as an art. While there are aspects of the deal and subsequent execution that undoubtedly will benefit from the deft touch of a talented leadership team, it never hurts to know the odds.

Know-how shortcomings—whether an overall lack of expertise or, if experts do exist, their being too busy or unwilling to dedicate themselves to the integration efforts—can also hinder a project team in dealing with integration challenges. Most companies do not possess the right skill set for post merger integration, largely because there is no need for an organization to have PMI know-how until it finds itself facing a PMI. These skills are highly specific and not something that, for example, a sales manager needs for day-to-day work. Yet PMI know-how is critical for line managers as they will lead the implementation charge, and it is essential that managers are recruited from the companies being merged. The lesser the PMI experience of line management in both organizations, the higher the project risks. External support can be invaluable, but it is not a substitute.

Even in cases where companies possess PMI know-how, these managers are usually not available to take on a post merger integration. This is because, typically, those with PMI skills are highly valued and likely to be put in charge of other initiatives and functions. Most companies are happy to delegate any available manager to the job, no matter what his or her skill set. Of course, project risks increase with less skilled management time dedicated to the post merger integration.

Numbers over myth

Post merger integration has long been treated as an art. While there are aspects of the deal and subsequent execution that undoubtedly will benefit from the deft touch of a talented leadership team, it never hurts to know the odds.

Our research on the PMI database does not provide lockstep marching orders on the road to success – mergers have never been a cookbook process. It does, however, highlight with quantitative rigor the risks that can make an inherently difficult process harder still. There are few certainties in life or mergers. But with clarity around which factors matter and which seem to be hearsay, we can make better informed decisions and stack the odds in our favor.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter