Publications Perspectives On Merger Integration

- Publications

Perspectives On Merger Integration

- Bea

SHARE:

A new generation of M&A: A McKinsey perspective on the opportunities and challenges

By Clay Deutsch & Andy West

Despite continued uncertainty, signs point to a surge in M&A activity that will be ambitious in both scope and profile. Even M&A veterans will require new tools for analysis and integration to manage these deals for maximum benefit – new organizational efficiencies, market expansion, employee development, product innovation, and profit. Mergers often accelerate in the second half of a downturn, which is where the economy seems to be these days. Prices are low. Competitors may be weakened. Businesses that may have disdained overtures, likely or unlikely, may be more receptive. Unusual numbers of executives and boards report seeing opportunities to make “once in a lifetime” deals.

At the same time, economic uncertainty has left many organizations cautious. Executives may be excited about the prospects, but their boards may be less convinced and willing to act because they doubt the company’s ability to manage an ambitious deal successfully.

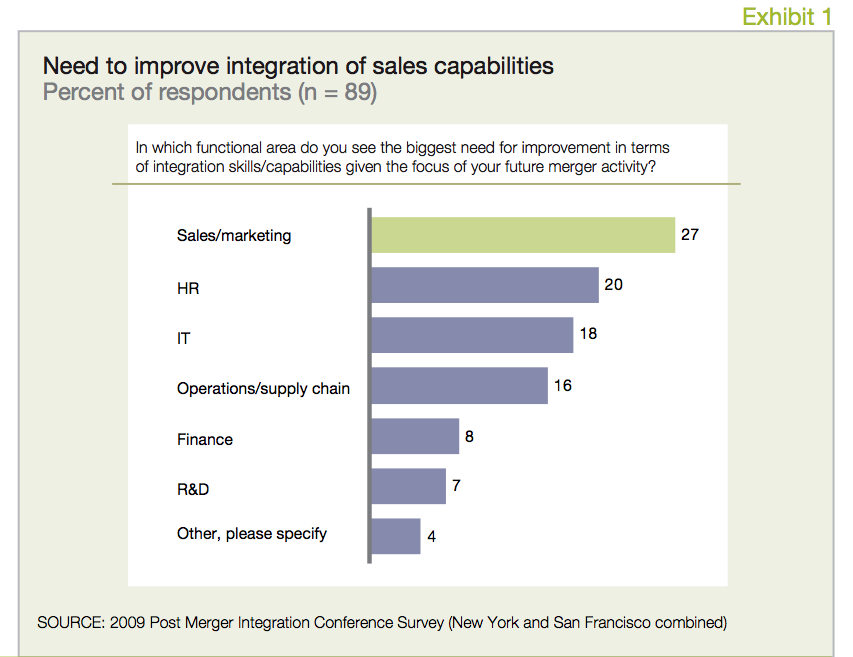

A McKinsey survey of almost 90 M&A professionals conducted in mid 2009 showed new interests and attitudes toward mergers. Nearly half of those surveyed believed the deals they manage would “increase in transaction value” over the next three years. Respondents expressed great interest in using M&A to move beyond existing lines of business into new strategic areas and build their R&D portfolios.

Of course, most acquisitions will remain focused on more traditional sources of value closer to existing lines of business, but any of these deals may bring opportunities to create transformational value that reaches far beyond the potential of conventional integration strategies. The survey and the M&A success of McKinsey clients indicate that transformational value can increase the return on an acquisition 30-100 percent.

Identifying transformational value opportunities and managing mergers that stretch a company’s capabilities in new ways require a dramatic departure from the traditional approach to integration that has emerged as best practice over the past 10-20 years – using templates, checklists, and strong process management to avoid risk. Even now, this approach produces M&A failure rates of 66-75 percent.

These numbers have reinforced the risk-avoidance mindset and encouraged deal assessment focused on answering two questions: Can we afford it? Can we buy it? But, as many acquirers discover to their (and their stockholders‘) dismay, the ability to buy may have nothing at all to do with the capacity to own.

Old vs. new approaches to integration

Building integration capabilities requires a new approach to managing the deal. In the traditional integration approach, the integration leader, teams, and consultants focus on preventing anything bad from happening until the deal is done. In a rapidly paced process, they try to secure a quick close and leave the issue of how to make the combination work for later. They aim to minimize risks and realize the cost savings associated with reducing redundant operations and people.

But many deals need to look beyond the value that justified the transaction, opening the aperture to find new sources of synergies and value. The survey showed that the due diligence in most deals can overlook as much as 50 percent of the potential merger value. Survey respondents also admitted that due diligence is inadequate in more than 40 percent of their deals. Companies clearly need to improve and expand their due diligence.

Great integrators understand that two very different types of value can emerge in most mergers – combinational and transformational. But because identifying and capturing transformational value requires a different and more difficult approach, most deal teams concentrate on the combinational at the expense of the transformational.

Certainly, limiting operational risk is essential to keeping the business running smoothly during integration. But the survey found that too few companies, including very experienced acquirers, are getting even the combinational basics right. They don’t plan and execute a thoughtful, end-to-end integration process. They don’t put the right leadership in place. And they don’t hone the skills needed to realize fully even the most obvious value from the merger.

When companies falter on these fundamentals, they have little chance of identifying and capturing transformational value. Success here requires:

• Deeper, stronger integration skills and intense management commitment

• An integration approach that’s flexible enough to allow leaders hip to pursue sources of transformational value along with combinational value

• Rigorous analysis and integration management that exceed the capability of too many companies and M&A professionals.

In the recovering business environment, more and more companies are considering bold, transformational moves. They will need to expand their M&A capabilities to handle deals outside their existing business lines, do more and/or larger deals, and identify and capture both transformational and combinational sources of value.

This calls for a new methodology and toolkit built around four distinctive capabilities that can close the skills gaps identified in the survey of M&A professionals.

Rigorous analysis of the value potential of the merger

This begins by rejecting the traditional risk-avoidance mindset, recognizing the need to look beyond traditional sources of value and being willing to ask the question, “When we own this asset, what are all the ways we could create value with it?” Taking a more expansive view to identify and quantify synergies requires a systematic approach that can locate value creation opportunities which often exceed due diligence estimates by 30-150 percent.

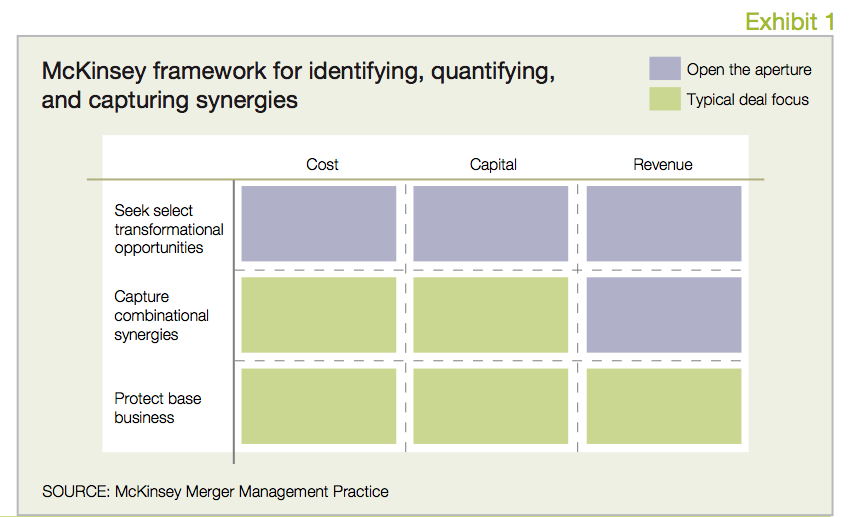

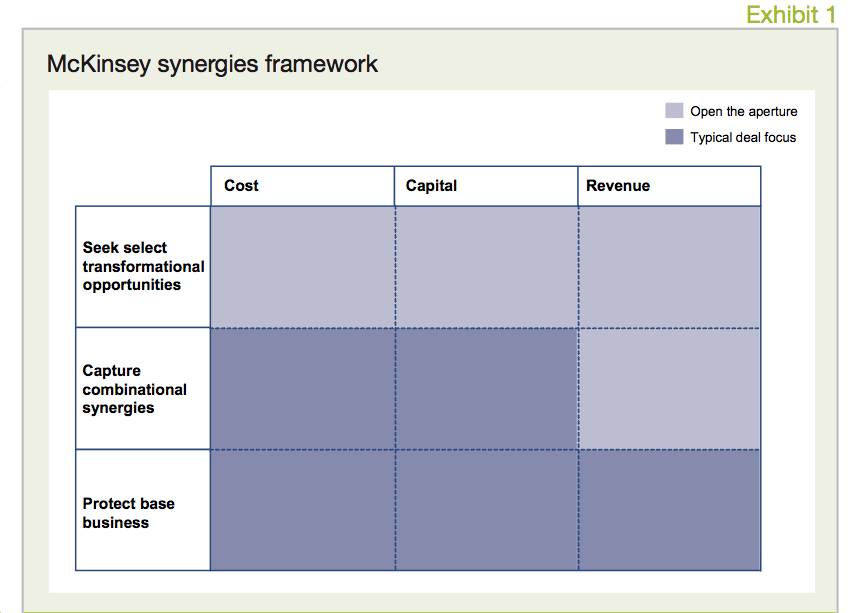

This broader view requires considering three layers of value creation:

• Protecting the base business, which includes efforts to preserve pre-merger value and maintain the core business

• Capturing traditional combinational synergies, which includes efforts to achieve economies of scale and enhanced efficiency

• Seeking select transformational synergies, which are often ignored, but are aimed at radically transforming targeted functions, processes, or business units.

Within each layer, companies have three options for realizing value:

• Capture cost savings by eliminating redundancies and improving efficiencies

• Improve the balance sheet by reducing such things as working capital, fixed assets, and borrowing or funding costs

• Enhance revenue growth by acquiring or building new capabilities (e.g., cross-fertilizing product portfolios, geographies, customer segments, and channels).

Intensive focus on the corporate cultures involved

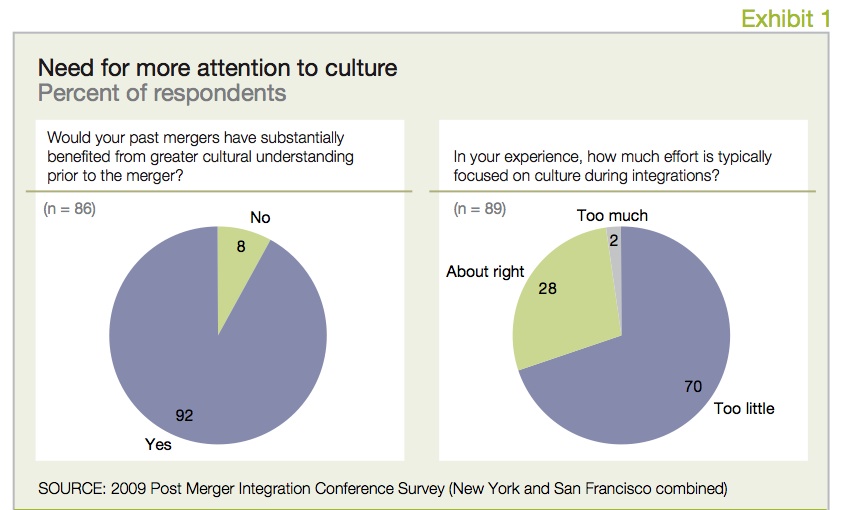

Ninety two percent of the survey respondents said that their deals would “have substantially benefitted from a greater cultural understanding prior to the merger.” Seventy percent conceded that “too little” effort focuses on culture during integration.

Part of the problem may be that, especially when integrating companies are in the same or similar businesses, their top executives tend to assume they are “just like us” and dismiss the need for deep cultural analysis. Likewise, when the CEOs in a deal get along with each other, they tend to assume that their companies will get along equally well. No two companies are cultural twins, and companies seldom get along with each other as easily as their executives might. In fact, the survey establishes that the issue of culture comes down to two fundamental problems: understanding both cultures and providing the right amount and type of leadership.

Culture clearly baffles most merger managers – which is probably the reason that virtually none of them use culture as a screening criterion. But few have had a tool for describing and analyzing carefully defined cultural characteristics for each company. McKinsey teams are bringing just such a tool to their clients, enabling them to understand vulnerabilities and similarities in the ways the businesses run and interact. The analysis pinpoints specifically how the companies differ, what is meaningfully distinct, and how to reconcile important differences.

A better approach to sales integration

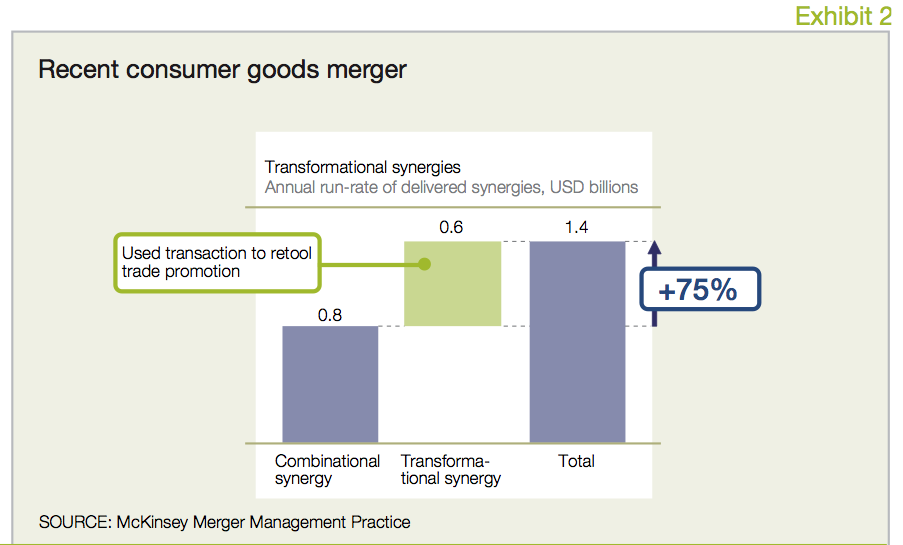

Almost one-third of the survey respondents called combining and developing the sales functions of the merging companies their greatest integration challenge. As M&A focuses increasingly on growth, a powerful sales force will be critical to breakthrough profitability.

Four steps essential to integrating sales forces effectively are often overlooked or missed:

• Share information about the integration process with customers and the sales force. Many companies take the opposite approach and are surprised when post-merger revenue fails to meet expectations.

• Win prominent accounts quickly to build momentum and generate internal confidence in the merger.

• Identify and retain essential support people, as well as sales reps.

• Review the merged portfolio of customers and make tough calls about who warrants new investments and who might be shed or given less attention.

Successful sales force integration also requires excellent execution of the basics, including detailed planning that identifies and taps the best managers and staff, sets ambitious sales targets, creates an effective program for retaining top talent, and spells out the best ways to cultivate the most promising customers. This planning should be an integral part of the merger process that proceeds in parallel with conceiving and valuing the deal, assessing synergies and culture, and devising the end-to-end merger methodology.

A unique period in M&A is looming. It will offer unprecedented opportunities to build new skills and methodologies to get mergers right, recognizing and capturing their transformational value. Successful integration efforts will share two fundamental characteristics: determination to achieve unprecedented goals for value creation and performance and executive courage and commitment to tackle the risks inevitably associated with such ambitions.

Beyond risk avoidance: A McKinsey perspective on creating transformational value from mergers

By James McLetchie & Andy West

Most mergers are doomed from the beginning. Anyone who has researched merger success rates knows that roughly 70 percent of mergers fail. Over time, this statistic has created an entire culture and practice of merger integration focused on avoiding failure: processes, IT solutions, checklists, and workplans, all crafted to ensure that integration avoids doom by sticking to its plan. “Don’t overcomplicate integration” is a common mantra. “Just follow the process and you will not fail” is another.

The problem is that avoiding risk can conflict with realizing the full value at stake in the merger. The issue begins with the fact that due diligence has only limited ability to set accurate expectations of the total synergies available in a deal. A recent McKinsey study found that 42 percent of the time, due diligence conducted before a merger failed to provide an adequate roadmap for capturing synergies and creating value.

In addition, the risk-avoidance mindset usually translates into an intense focus on pure process that can actually hamper an organization’s ability to adapt and capture emerging or unforeseen sources of value from a deal.

For example, in one unsuccessful software deal, a relentless focus on running the process limited discussion of the real opportunity, which lay in leveraging two very different sales models for top line growth. Specifically, integration teams concentrated almost entirely on tracking detailed interdependencies, leading to pages and pages of process analyses. Integration leadership spent relatively little time thinking about the game-changing opportunities to create value, e.g., driving implementation of new but practical approaches to cross-selling. In this case consistent over-attention to process and under-attention to value creation resulted in the merged company’s stock price lagging the market and its primary competitor.

Yet M&A is critical for long-term survival. McKinsey research found that acquirers who truly outperform over time strike the right balance between traditional best practices, or “combinational” activities, and “transformational” activities – those that maintain the flexibility to identify and capture new sources of value which emerge during integration planning.

Great integrators begin by distinguishing between combinational and transformational opportunities and then pursue them in tandem. To generalize, successful integrations capture combinational value, but the best integrators find specific transformational opportunities that go beyond these basic synergies to create tremendous additional value.

Striking the right balance – implementing traditional best practices where appropriate without limiting flexibility where required in the search for value – requires three actions that go beyond risk avoidance:

• Taking an expanded view of value during integration and setting the right stretch aspirations and targets

• Looking beyond current integration approaches to capture targeted opportunities for transformation

• Committing fully to targeted transformational efforts.

One caveat: this article focuses on capturing value from mergers, not pricing them. Acquirers are rightly risk-averse in what they pay for, and pricing inherently risky transformational value into a deal before integration planning has taken place is not necessarily appropriate. But once a deal is concluded, restricting integration planning to the necessarily conservative synergies that formed the basis for the transaction price is equally unwise.

Taking an expanded view of value and setting the right stretch aspirations and targets

To understand the sources of value in deals, we organized all value into two categories – combinational and transformational. While this is an obvious oversimplification, it reflects genuine tendencies in most mergers and enables us to identify characteristics that differentiate truly successful mergers from merely average ones.

Combinational synergies rely on merging operations, resulting in scale economies and/or basic scope economies (for example, cross-selling existing products), as well as protecting value by ensuring business continuity. These synergies are the least risky, easiest to quantify, and most easily managed with a repeatable process (such as synergy benchmarks). They also represent the type of value that is most often the cornerstone of valuations. Not surprisingly, most integrations work predominantly on combinational synergies – often underplaying more complex, more profitable sources of value.

Transformational synergies, in contrast, typically come from unlocking one or more long-standing constraints on a business. This change can come from the impact of the merger itself or the role it plays in “unfreezing” the organization. Transformational synergies represent huge potential for breakthrough performance.

But because transformation involves complexity that often exceeds management’s capacity, it can also bring the business to a grinding halt. Management needs to focus selectively – on a handful of targeted functions, processes, capabilities, or business units that make breakthrough performance possible and financially worthwhile.

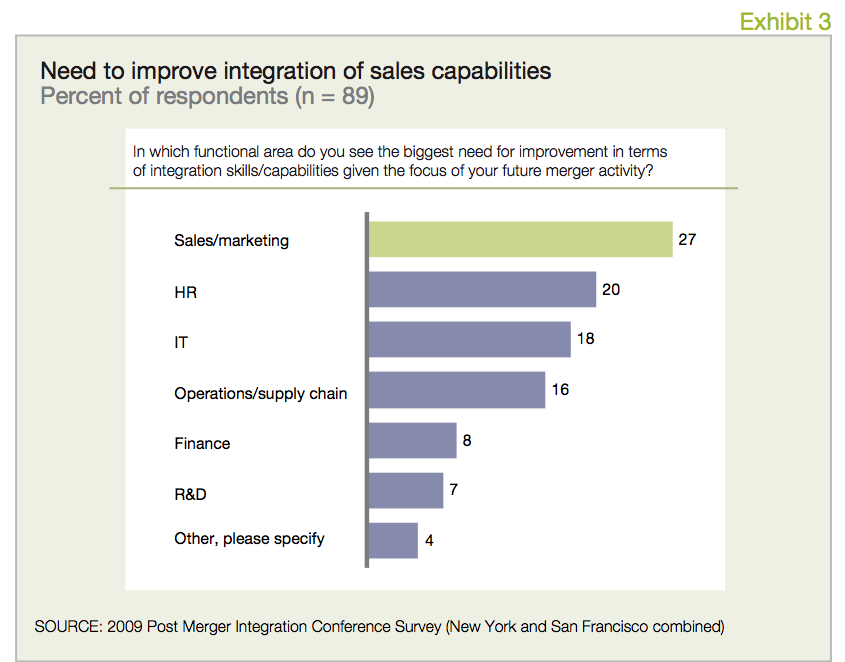

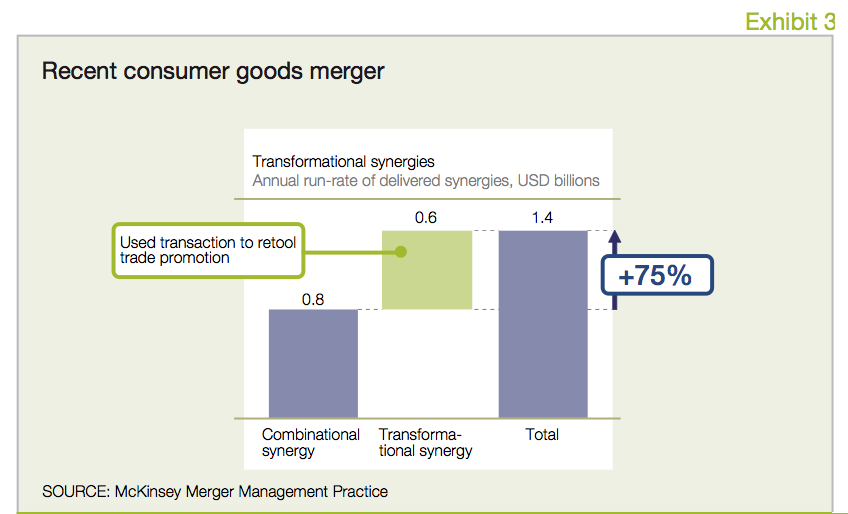

Consider the recent merger of two major consumer goods companies. Recognizing the superiority of the target’s innovative approach to distribution management, the acquirer assigned its top integration team the task of figuring out how to incorporate that approach into its own entrenched distribution practices. Their success boosted the value of the deal 75 percent.

Companies contemplating transformational synergies must assess their readiness to capture each opportunity but must not shy away from an opportunity simply because it looks risky or falls outside a pre- set process or due diligence baseline.

The McKinsey study built a database of large transactions (where the target represented a meaningful enough proportion of the acquirer’s business to affect share price) and identified a subset of companies whose performance improved significantly after a merger or acquisition. Profiling several of these companies in detail showed each able to move beyond combinational sources of value and find something truly transformational to capitalize on.

Consider a recent high tech merger in the top portion of the performance profile. An entrepreneurial, low- cost manufacturer with a presence limited to one region acquired a player with a larger global brand and leveraged that company’s network for high-margin leadership in all markets.

The company not only did an adequate and structured job in approaching the combinational aspects of the merger, but also made significant investments in ensuring the realization of the more transformational aspects of the deal. The company replaced over 35 percent of the senior management team with outsiders expert in realizing the new vision of the organization. Corporate headquarters moved from the acquirer’s geography to a new geography that represented the future of the business. The company also seized the opportunity to radically change its go-to-market model and supplier relationships.

Early realization of significant cost synergies, e.g., procurement and supply chain, funded the more transformational strategic shifts, but the view from the beginning had been that the deal should trigger transformation. The result was major value creation. Whereas the acquirer’s total return to shareholders had lagged the industry by an average of 42 percent in the two years before the merger, it outperformed the industry by 27 percent in the two years after the deal.

Another example is an automotive merger that created tremendous value by rebuilding the acquired company’s traditional relationship-based procurement system, replacing it with a profit model that cut costs dramatically. The combinational aspects of the deal did not go ignored, but they also did not prevent the organization from dismantling a process and program that represented 20 years of operations excellence. The effort helped to define the company as a global player – embracing a new model that represented the next 20 years of procurement excellence.

Simply focusing on bringing existing programs together or absorbing the acquired processes into the parent’s would have been much easier, but would have meant less risky integration at the cost of truly transformational value. The chosen course required radical change in the company’s culture and real leadership and focus by the executive team, but was clearly worth the investment.

Looking beyond current integration approaches to capture targeted opportunities for transformation

Just as combinational and transformational synergies differ in nature, so do approaches to capturing them. For example, the mantra in pursuing combinational value is: simplify, de-risk, be practical, do things fast. Value comes from managing and effectively limiting options, instead of creating new ones, and moving quickly to prevent the integration from distracting attention from “real” business. The focus is on managing process and ensuring that baseline joint operating capabilities are in place on day #1. Best-practice managers seek to:

• Limit the changes in how a business runs before and after legal close

• Focus ruthlessly on hitting announced, typically conservative synergy targets

• Deploy ever more refined process management tools to ensure that, as one leading serial integrator put it, “we never invent anything twice or make the same mistake again.”

Capturing combinational value in these ways is the appropriate territory of classic program management offices.

Transformational approaches, on the other hand, are usually far more fluid and experimental, as they reach into unfamiliar territory and likely involve unusual combinations of people, process, and technology. Transformational value creation can therefore be quite disruptive for those involved.

Transformational activity typically proceeds on a longer timescale, allowing time for brainstorming, testing, piloting, and building capabilities. Maintaining momentum and energy usually requires some early wins to earn permission for transformation, but efforts to capture transformational value are likely to run well beyond the traditional 90 days of integration planning.

The success of transformational approaches typically hangs on:

• Creating across-functional team dedicated to locating breakthrough opportunities

• Setting bold goals for value creation

• Providing incentives with real upside for breakthrough performance.

Capturing transformational synergies demands disproportionate senior executive time. The CEO in the consumer goods merger mentioned above met twice as often and twice as long with the breakthrough team lead than with the leads of the other 12 integration teams; the breakthrough team delivered more than 40 percent of the total synergies.

Setting aspirations involves more than setting a high target – it’s about stretching people along multiple dimensions and rooting the stretch in well-investigated facts. Managers should start by systematically exploring synergy ideas across cost, revenue, and the balance sheet. They should ground the aspirations in analytical insight, not gut feel, to avoid having to negotiate what is or is not a reasonable stretch.

The best examples we uncovered used the analytical process of setting synergies not only to anchor but also to ratchet up aspirations. After reviewing detailed synergy plans and realizing that a different organizational construct could yield far more value, one CEO demanded that certain teams linked to his transformational themes come back with “twice the synergies, delivered in half the time.” While hugely challenged, they delivered. (See the section on cross-functional synergy workshops.)

Transformational efforts typically run in parallel with established integration processes, so each approach can operate at its full potential. To understand how these efforts can work in parallel, consider a global mega-merger with a multi-billion-dollar cost synergy commitment. In a two-day synergy workshop, leaders identified, quantified, and prioritized both combinational and transformational value levers.

The combinational levers included plans for immediate reduction of overlapping headcount and overhead costs and procurement synergies arising from consolidating vendors and reducing duplicative spend on marketing and IT.

The team also defined a number of “model-shifting” initiatives, including a new industry-changing sales force model to deliver more product to customers more efficiently – in other words, having a smaller sales force get more product into customers’ hands. The shared services team located opportunities to redefine the support model far beyond existing practices, capitalizing on opportunities in sales administration, IT, procurement, finance, legal, and even R&D. Other teams found other such “radical” ideas. In all, these ideas generated an additional 30-50 percent in revenue growth and cost reduction opportunities.

The company implemented the sales force model just after deal close and sequenced the shared services changes after a major ERP initiative. By looking at the deal and sources of value early and more comprehensively, integration leadership defined and sequenced the transformational opportunities in line with the immediate combinational plans.

Cross-functional synergy workshops

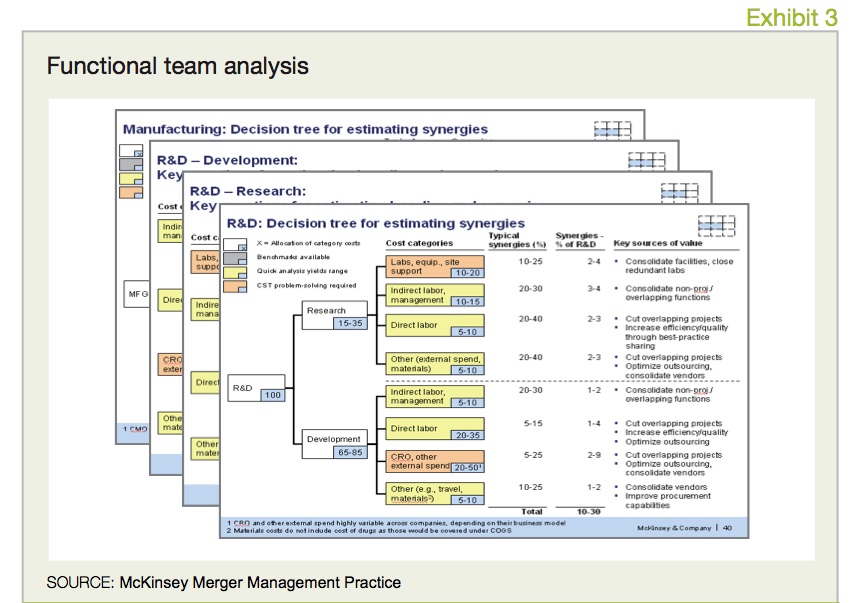

Many companies contemplating their merger options find that they get farther faster by organizing synergy workshops of cross-functional teams than by completing cycle after cycle of business plan templates. In a recent pharmaceutical merger, this approach uncovered almost 40 percent more synergies than a rigorous bottom-up spreadsheet-based approach had identified.

These one- or two-day workshops look for ways to meet synergy targets and then create realistic plans for achieving the targets.

The teams develop initial ideas for reaching the targets, analyze data to see if the ideas will work, and then brainstorm options that might capture even more value. The focus is on new ideas and challenges, not numbers.

The entire group reviews the ideas and agrees on which to pursue. By the end of the workshop, targets are often reset at higher levels, and people have committed to the plans.

These workshops are intense, but people are energized by the opportunity to engage with colleagues in shaping ideas. They leave with much greater ownership of the targets and plans – partially because they had the space to debate concerns about what could and could not work. There’s also a palpable sense of relief at not having to fill in yet another template.

Committing fully to targeted transformational efforts

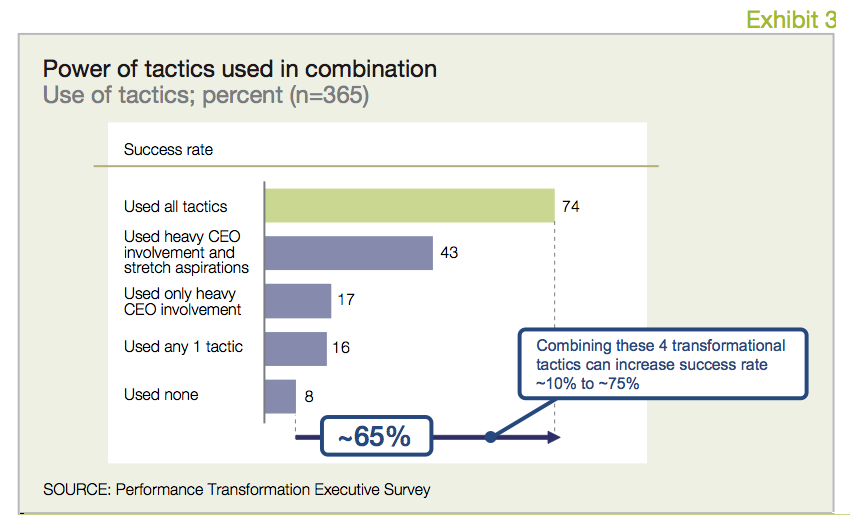

The courage to move beyond risk avoidance is the starting point for creating transformational value in a merger. When pursuing transformational synergies, successful companies expand their core integration approach in four ways:

• The CEO or business unit leader participates actively in the effort to capture transformational value (for example, by personally leading key initiatives).

• The company sets clearly defined stretch aspirations, in financial or operational terms, that represent a genuinely new level of performance.

• Staff feel owners hip for changes, do not focus excessively on process, and are energized and mobilized to develop new ideas to create value.

• The integration has a readily understandable structure, with distinct responsibilities and parallel efforts to pursue combinational and transformational sources of value.

A recent study of over 365 managers involved in 310 deals between 2003 and 2008 found that success requires commitment to employing all four tactics. Mergers that did so were much more likely be self-rated “extremely successful” than those that deployed only one or two tactics.

Mergers offer exciting opportunities to shape new business models, innovate, ramp up growth, and deliver breakthrough performance. While classic integration management is essential for controlling the many risks that mergers create, it often stands in the way of the complex, strategic efforts needed to capture transformational opportunities. Those efforts require unparalleled aspiration and commitment from CEOs and other senior leaders, often repaid with the most memorable moments of their careers.

Opening the aperture 1: A McKinsey perspective on value creation and synergies

By Oliver Engert & Rob Rosiello

Almost 50 percent of the time, due diligence conducted before a merger fails to provide an adequate roadmap to capturing synergies and creating value. Typically compiled in haste, and concentrated on determining fair market value, this outside view often ignores critical sources of additional value offered by synergies between merging companies.

Traditionally, companies merged to achieve scale within an industry or reduce costs. Today many companies turn to mergers for new capabilities or access to adjacent businesses with which they may have limited experience. They need to open the aperture, looking beyond the traditional sources to achieve maximum value. They need to answer the question, “Now that we own this asset, what are all the ways we could create value with it?”

Identifying and quantifying synergies requires a systematic approach. McKinsey has developed a framework to guide the effort. This framework can help companies locate value creation opportunities that exceed due diligence estimates by 30-150 percent.

Overview of the framework

Putting new emphasis on transformation and revenue, the framework opens the aperture so companies consider the full range of opportunities to derive maximum value from any merger.

Layers of value creation

The framework defines three layers of value creation:

• Protect the base business: efforts to preserve pre-merger value and maintain the core business

• Capture combinational synergies: traditional value creation efforts to achieve economies of scale and enhanced efficiency

• Seek select transformational synergies: often ignored, often capability-based opportunities to create value by radically transforming targeted functions, processes, or business units.

Levers of value creation

Within each layer of value creation, companies can pull three levers to realize value:

• Cost: capture cost savings by eliminating redundancies and improving efficiencies

• Capital: improve the balance sheet by reducing such things as working capital, fixed assets, and borrowing or funding costs

• Revenue: enhance revenue growth by acquiring or building new capabilities (e.g., cross-fertilizing product portfolios, geographies, customer segments, and channels).

Of course, cost, capital, and revenue opportunities differ by value creation layer. But mapping the full range of opportunities reveals the entire landscape of synergies that a merger might tap to create value. (See the section on four types of synergy targets.)

Protect the base business

This is not as straightforward as it sounds. McKinsey research has found that acquirers typically see sales decline eight percent in the quarter after announcing the deal.

Companies with significant merger experience avoid this pitfall by concentrating on:

• Keeping the business running, including maintaining accountability for current-year results and making the investments required to sustain quality

• Separating integration efforts from running the business, with integration managed by an integration office staffed with high-caliber people

• Shortening the post-announcement, pre-close period and announcing the new management team as early as possible

• Retaining customers and important talent through shared aspirations, clear communication,and appropriate incentives.

But their zeal to achieve due diligence targets often makes even experienced companies myopic. They overinvest executive attention and integration talent in that effort, failing to protect the base business or organize clean teams that could scope the full landscape of value creation opportunities so the combined company could begin to profit on day #1.

Capture combinational opportunities

Most efforts to capture combinational synergies focus, at least initially, on cost and capital. These efforts typically exceed “expected” short-term estimates. But because they rely on across-the-board rules of thumb and ratios, they often underestimate savings, leaving money on the table. One company met its due diligence targets six months ahead of schedule. But a new business unit head who arrived at that point found 20 percent more than originally estimated by taking a clean-sheet approach.

Meanwhile, a company focused only on cost and capital is overlooking the growth opportunities represented by revenue synergies. Historically, many companies shied away from the uncertainty and risk associated with these synergies early in merger planning. But when less of a merger’s value lies in cost or scale, revenue synergies loom larger in value creation and need immediate attention. In many industries a one percent increase in revenue growth creates more value than a one percent increase in EBIT. Failure to consider revenue synergies from the start may delay realization of any value from them by a year or more.

Companies that avoid this pitfall often organize cross-functional teams to define ways to meet synergy targets and develop realistic plans for achieving the targets.

Four types of synergy targets

1 Targets announced publicly

2 Targets requiring minimum achievement above announced targets

3 Targets set top-down and bottom-up to exceed minimum achievement targets

4 Aspirational targets

Seek select transformational opportunities

Transformational synergies represent huge potential for breakthrough performance. But because transformation involves complexity that often exceeds management’s capacity, it can bring the business to a grinding halt. Management needs to focus selectively – on a handful of targeted functions, processes, capabilities, or business units that make breakthrough performance possible and financially worthwhile.

Consider the recent merger of two major consumer goods companies. Recognizing the superiority of the target’s innovative approach to distribution management, the acquirer assigned its top integration team the task of figuring out how to incorporate that approach into its own entrenched distribution practices. Their success boosted the value of the deal 75 percent.

Such success typically requires creating a team dedicated to locating breakthrough opportunities, setting bold goals for value creation, and providing incentives with real upside for breakthrough performance. Capturing transformational synergies requires disproportionate senior executive time. The CEO in the consumer goods merger met twice as often and twice as long with the breakthrough team lead than with the leads of the other 12 integration teams. The breakthrough team delivered more than 40 percent of the total synergies.

Companies contemplating transformational synergies must assess their readiness to capture each opportunity:

• Will we have the capabilities and financial means required for success?

• Do we have enough appetite for risk and full executive commitment?

• Can we stay the course until we realize value?

• Are we willing to break some glass to capture the opportunities?

With economic recovery looming, interest in mergers is reawakening as companies seek new ways to benefit from the upturn. The McKinsey framework for identifying and quantifying synergies can help ensure they weigh and balance all their options for realizing value from a merger.

Opening the aperture 2: A practical guide to capturing synergies and creating value in mergers

By Oliver Engert, Eileen Kelly, & Rob Rosiello

Most companies contemplate mergers with great ambitions, but their vision quickly narrows to cost. Best-practice companies, on the other hand, keep their eye on the big picture and apply the thinking mapped in the McKinsey framework to identify, quantify, and capture synergies. Using this approach effectively requires following a disciplined, systematic process.

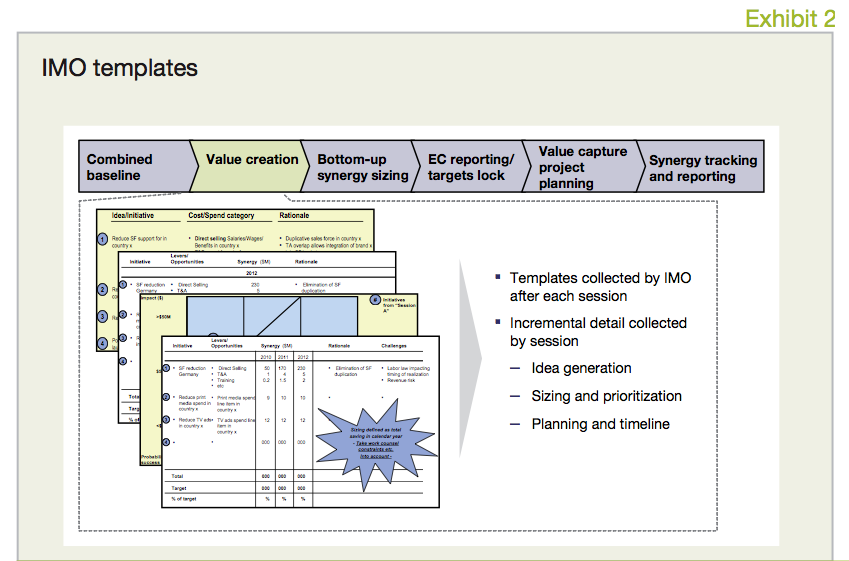

This process involves six steps for capturing value, from creating a combined company baseline to defining rigorous mechanisms for tracking and reporting synergies captured. This process starts as soon as the deal is announced to ensure that the new company begins to realize value on day #1.

The first two steps, typically the first 45 days, are critical but often get short shrift. This is the time for leadership to define the vision needed for integration to succeed. Even the financial exercise of step #1 represents an opportunity to set the tone of the merger by urging candor and constructive challenges.

1. Combined baseline

This step develops an overview of operating expenses, revenue, and the balance sheet for the combined company before factoring any synergies into the picture. The overview lays the foundation for identifying opportunities to create value, assigning them to appropriate owners, and planning ways to execute and then track and report results. Many CEOs and even more CFOs tell us they wish they had taken the time to develop a more robust baseline. As one CFO reflected, “If you don’t have a robust baseline, it’s like building a skyscraper on quicksand.”

Creating the baseline is often time-consuming, as getting information on the target company and allocating expenses to the right function or organization can be difficult – and politically charged as competition for budget can be fierce. But the effort pays off because integration proceeds with a clear, shared sense of the financial landscape.

2. Value creation summit

The summit is an equally critical step in the process. It helps keep the aperture open, encouraging people to put aside initial perspectives from due diligence, to apply a rigorous synergy framework, and to look beyond traditional sources to achieve maximum value. The summit provides a forum for the collaboration and creative thinking needed to generate rich ideas for synergies that promise to create real value, especially ideas that can lead to breakthrough performance. The summit brings together the acquirer’s integration leadership, the leaders and content experts of the functional teams, and McKinsey industry, integration, and functional experts to think top-down about potential synergies.

The summit generates:

• A prioritized list of opportunities that reflects the irrelative size

• A list of value creation opportunities that looks beyond cost to consider capital and revenue opportunities

• A high-level implementation plan that maps the timing of capturing synergies, including three or four milestones.

The Integration Management Office (IMO) provides templates for these deliverables to ensure consistent efforts across functional teams. This consistency is important to sizing synergies, setting priorities, balancing efforts, and tracking progress.

3. Bottom-up synergy sizing

The functional teams take the synergies identified as high priorities during the summit and further refine them by thinking bottom-up. The teams detail the components of the synergies established by the top-down thinking of the summit and determine the component-level synergy potential.

Looking more deeply into synergies yields richer, more specific insights, especially important interdependencies to explore and the time likely needed to realize each opportunity. Companies often underestimate the time and resources needed to capture an opportunity. This step helps them avoid that pitfall.

4. Executive Committee reporting/targets lock

The Executive Committee and IMO leadership regroup to review the output of the first three steps and set final synergy targets. This marks an important point in integration planning, as the focus now shifts from what value to capture to how and when to capture it. Leadership should take the integration pulse and launch any actions needed to sustain momentum and ensure accountability.

5. Value capture project planning

Under the direction of the IMO, the functional teams define initiatives to achieve synergy targets. The IMO plays a central role in aligning team priorities and resolving cross-team dependency issues, as well as developing cross-functional, value-capture teams for the most significant opportunities. The IMO also creates a dashboard to help senior management monitor integration performance.

The most critical component of value capture project planning is establishing ownership of the targets and plans. Passing the targets and plans down to the line isn’t enough. Each business unit leader must help drive the planning process forward, including assuming responsibility for targets and plans.

6. Synergy tracking and reporting

After deal close, rigorous tracking at the team and executive levels keeps initiatives on track and locates new sources of value. At this point team members often get distracted by the demands of their “day jobs,” but systematic and timely review of progress against goals remains essential to ensuring full realization of the potential value of the deal.

As economic recovery looms and companies look to mergers as a way to benefit from the upturn, they need to understand their options. The McKinsey process can help them weigh and balance opportunities to realize value from a merger.

Next-generation integration management office: A McKinsey perspective on organizing integrations to create value

Mergers offer tremendous opportunity to create and sustain breakthrough value, especially for companies that get three mutually reinforcing attributes right: pursue transformational as well as combinational sources of value; target a new level of synergies; and understand and address the merging companies’ points of cultural incompatibility.

The traditional program management office (PMO), focused on process, is poorly suited to handling the complex, often disruptive change typically needed to achieve breakthrough value in a merger. Instead, CEOs must establish a new breed of integration management office (IMO) – viewed, designed, and operated as a highly empowered vehicle to realize deal strategy and deliver value.

Profile of the IMO

This value-focused IMO should report directly to a CEO-led Steering Committee and be staffed with the company’s top performers. Indeed, it should be conceived as a vehicle to test and reveal the “leadership of tomorrow.” The IMO experience gives these future leaders significant exposure across the entire organization.

For this reason, the IMO team requires careful selection: in McKinsey’s experience, more than 70 percent of integration leaders assume more senior roles post-IMO. At one high tech company, senior leaders must have served as an integration leader on their path to the executive suite.

In addition to having top-caliber leadership, strong IMOs share three characteristics:

• They can conduct the rigorous analysis needed to support aggressive, stretch synergy aspirations.

• They take the lead in generating ideas for creating value and constantly re-energizing the integration process around ambitious goals. For example, in a year-long merger process between two multinationals, the IMO held a major global event every 6-8 weeks, bringing together key players to develop ideas and build momentum.

• They do not see process management as their primary focus, but they nonetheless apply rigorous mechanisms to track progress against milestones and hold people accountable for achieving results.

The central task of the IMO is to orchestrate pursuit of the major value creation opportunities presented by the merger. For example, a global healthcare IMO accelerated the combined company baseline to drive 40 percent higher targets through comprehensive analysis of projects.

Supporting IMO roles

Supporting this objective, the IMO must play several other roles. It must manage the complexity inherent in most mergers, building robust yet simple processes that surface and resolve thorny issues and facilitate value creation.

Further, the IMO should take the lead in identifying and developing the capabilities needed enterprise-wide to capture transformational value opportunities, such as a step-change in customer intimacy or a radically enhanced supplier negotiation capability. Indeed, the best acquirers have used mergers and the integration structure to build unique organizational capabilities for the future – well beyond the immediate needs of the integration.

An often overlooked but highly impactful role of the IMO is to address organizational compatibility, or culture, issues. It can take the lead in understanding and assessing the culture of the merging entities “going in,” especially the cultural incompatibilities that represent the greatest obstacles to deal success and performance. This intelligence should inform integration design, the choice and profile of integration leadership, and ultimately the way the IMO runs day to day – as well as the broader organizational design and governance model for the merged entity.

In a global mega-merger, the CEO and his integration leadership faced an incumbent culture where functions operated as silos, using meetings for “extreme collaboration” – code for slow decision making. The IMO needed to address this problem early, since 50 percent of synergies were expected in year #1. Accordingly, the IMO “forced” cross-functional interaction and rapid decision making – for example, organizing targeted special teams (legal entity, branding, product labeling, and so on) to handle cross-cutting strategic or value capture initiatives.

The new culture was also expected to drive rapid decision making. Eventually, the weekly IMO meetings held integration leaders accountable for decisions and timelines more aggressively than the general company culture. While this approach was tough at first, the front line of future leaders and the IMO itself became highly visible role models of the new, “can-do” culture.

What, then, does a next-generation IMO look like in practice? Its purview is cross-functional, as it must drive decisions across functions, business units, and divisions at a faster pace than the current organizational construct allows. For this reason, the IMO should be a microcosm of the existing company and governance model, with its own empowered “CEO” (Integration Leader), “CFO” (Value Creation Lead), and Executive Committee (Steering Committee).

The IMO is the “orchestra” of the deal: an ensemble of different talents playing their “instruments” together in a coordinated sequence, led by a respected “conductor,” in a highly visible performance that – at its best – delivers work worthy of a standing ovation. (The author wishes to acknowledge Sarena Lin’s contribution to this article)

Integrating sales operations in a merger:A McKinsey perspective on four essential steps

By Ajay Gupta, Tom Stephenson, & Andy West

Make no mistake: mergers are challenging. But they can provide organizations with transformative possibilities. One of the biggest opportunities – integration of sales forces – is central to ensuring revenue growth and capturing the value that mergers promise but often fail to realize.

Yet integrating sales forces ranks among the hardest parts of a merger to execute – a fact not lost on senior executives.

Mergers generate anxiety inside and outside the companies involved, and competitors happily exploit such fears to woo star salespeople and poach customers. Nonetheless, savvy companies embrace the opportunity to build a new sales organization that is more than the sum of its parts.

Four steps are essential to facilitating successful integration of sales operations:

• Understanding the importance of sharing information about the integration process with customers and the sales force tops the list. Many companies take the opposite approach and are surprised when post-merger revenue fails to meet expectations.

• The combined sales team must quickly win prominent accounts to build momentum and internal confidence in the merger.

• The executives running the integration effort must recognize the need to identify and retain essential support people, as well as sales reps.

• Senior managers should review the merged portfolio of customers and make tough calls about who warrants new investments and who might be shed or given less attention.

With careful planning and implementation, acquiring companies can revitalize not only their own organizations but also their relationships with customers. (The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Sophie Birshan, Kameron Kordestani, and Sunil Rayan to this article)

Overcommunicate

Some companies try to shield their customers from messy merger-related activities, such as changes in organizational structures and roles, customer engagement rules, and customer support. But most customers are willing and even eager to help a merging organization reshape itself. They prefer to participate in – rather than learn after the fact – the coming changes.

Mergers therefore give companies a chance to improve relationships with customers and address their unfulfilled needs. Many organizations are loath to make new commitments during a time of transition – they believe that management has enough issues to resolve without involving customers in the merger process. Yet such discussions are critical in determining what a merger can and can’t achieve and the role customers can play in shaping that outcome.

Leading companies therefore take an expansive view of their relationships with customers, discussing not only the details of the sales relationship – the nuts and bolts of what’s bought and sold and at what prices – but also such issues as contracting, delivery, support, and even the frequency of meetings between executives from both sides. Communicating openly and involving customers make them feel that their needs and expectations are being addressed and make them a party to merger success.

Consider what happened at a networking equipment company that found its customers worried about its postmerger product road map – the schedule specifying product ranges, prices, release dates, and other such details. Competitors fed this anxiety by questioning which products the merged company would support after integration, implying that there was too much uncertainty to do business with the company. In response, the company developed an integrated product road map before the merger even closed, so it could work with customers and launch a campaign to publicize its revamped product lineup as soon as the deal was completed.

That experience conveys another valuable lesson: involve salespeople in the integration process. Because most of them need to maintain a laser-like focus on revenue targets and compensation in order to succeed, many companies seek to protect them at this point so they can concentrate on customers and continue to make sales.

The problem is that customers and salespeople react negatively to ambiguity. Uncertainty about the organization’s structure, customer engagement rules, product road map, or operational details can all slow revenue generation as customers spend time discussing the issues and planning for the worst. Without firm direction, salespeople trying to quiet these concerns may give answers that are ultimately inconsistent with the developing integration plan, so the reps seem out of the loop or the organization looks unresponsive or incompetent. Sales reps also need reassurance about internal issues, such as how they will be compensated and who will cover which accounts. Otherwise, high performers may defect to competitors.

In short, ambiguity – not the distraction of integration itself – is the fundamental enemy. Best-practice acquirers define, as specifically as possible, how the merged organization will eventually look and how integration will proceed. Managers can’t know all the answers, but they should describe their intentions and the criteria for decisions and commit to answering the field’s questions at a specific pace and timing.

Best-practice acquirers also track progress carefully. They monitor the sales integration process closely: following not only lagging indicators, such as revenue, but also leading indicators, such as how much training on new products is happening, how long deals take to close, how often prices or contracts must be altered, how much sales shrink, and how many customers previously served by both merging companies are won or lost.

Build sales momentum

Best-practice integrators know that the first 100 days after a merger closes are critical to demonstrating its value and tangible benefits to the sales force, customers, and investors. These companies focus on winning a few critical large transactions early as proof-of-concept cases, using the full weight of the top team, product development, salespeople, and technical support.

Sales of products identified as quick wins – those most easily sold initially to customers of both merging companies – provide an immediate, focused experience for the sales force. At the outset, sales performance incentives should target such transactions.

In the case of a semiconductor merger, for example, much of the deal’s value reflected the possibility of integrating products into a combined chip set. Because the merging companies persuaded a few key customers to commit quickly to this vision, sales reps felt reassured that the deal was sound and would help them succeed both in sales volume and compensation. The early sales in turn generated enthusiasm and revenue momentum among other customers as well.

One barrier to achieving such early sales success is the time needed to bring together the merging companies’ back-office systems and processes, particularly IT and finance – a problem that can hamper the execution of orders. Excitement around a deal typically lasts six to nine months, not long enough for operations and IT to build a strong, integrated foundation for sales systems and processes.

The challenge of such long-term planning can put a deal’s early sales momentum at risk. Leading integrators accept the reality that momentum and a seamless transition may require temporary plug-and-play solutions for IT and finance. These workarounds ensure that sales reps can make forecasts, enter joint orders, gain pricing approval, manage exceptions and orders that need to be expedited, and troubleshoot issues in sales crediting and compensation. Longer term, the merged company will have time to cherry-pick each organization’s strongest processes, methodologies, and tools.

Look beyond sales reps

There is little argument that retaining top sales force talent is critical, and it’s easy to use pure revenue statistics to decide who stays and who goes in any integration effort. Yet all organizations employ certain people whose contributions are less easily measured but who are nevertheless the glue of a high-performing sales team.

Best-practice integrators identify these people and their place in the organization’s internal network and target them for retention. They may, for instance, be sales support staff in functional areas like IT and finance who have unique and specific technical expertise in sales processing or approval.

In many start-ups and medium-sized enterprises, some people play many roles. Organizations can map such an internal network by using a variety of techniques to ensure that the people who hold it together stay. Otherwise, an overly rigid or out-of-touch HR process for categorizing employees risks losing the richness of these relationships.

Finally, companies must consider the sequence for unveiling the integrated sales unit and selecting staff for retention. Reorganizing the frontline sales staff and back-office support simultaneously can disrupt customer service significantly. Deferring changes in support functions until account coverage and related matters have been resolved may help ensure uninterrupted customer service.

Review the customer portfolio

Most sales organizations in a merger focus on retaining all customers, regardless of expense. That’s natural, given the heightened awareness of competitors’ actions and the desire to show that the company is meeting revenue expectations. But mergers provide an opportunity to refocus on the most important and promising customers and to allocate resources to meet their needs more fully.

While altering long-standing customer relationships is never easy, best-practice integrators use the merger process to evaluate a portfolio critically. To ensure that they focus on the most profitable accounts, they examine the true cost of serving customers – support activities as well as sales rep time. They explore options for reallocating account resources, which may mean reducing coverage for customers receiving top-tier service because of historical relationships rather than profitability. And these integrators are willing to have difficult conversations with customers – discussing contracts, terms and conditions, pricing, and anything else that affects account profitability.

Sometimes, a company must be willing to shed customers. A technology company, for example, acquired a smaller firm that had been using its engineering team as a quasi-sales force. Customers had come to expect customization of products for them. Once the two organizations merged, the acquirer refocused the team on core engineering. The decision cost some sales to smaller customers, but the increased engineering productivity more than offset the net effect on profitability.

Integrating sales organizations is never easy. But companies can make real progress by involving customers and employees in the merger process, generating momentum by quickly winning key accounts, retaining critical staff, and serving the right customers in the right way. These steps can ensure that the sales force helps, rather than hinders, a merger’s overall success.

Case study: Rapid sales force integration

Following a merger, executives must decide how fast to integrate sales forces. Moving too quickly invites a clash of corporate cultures, sagging morale, and lost sales momentum. Moving too slowly leaves employees and customers in limbo, with competitors only too willing to poach accounts and top salespeople.

The president of one leading medical-device company chose sooner rather than later. He set the ambitious goal of presenting a single face to customers within eight weeks after closing a merger with a rival. Within two months of the deal’s close, senior management had to decide the fate of more than 300 sales reps and accounts totaling several hundred million dollars.

The aggressive timeline called for careful, systematic, and rigorous planning. Immediately after the merger announcement, the leadership of the two companies’ sales operations went to work. Both companies had a record of solid performance and a strong culture, yet differences were already apparent.

• One company had a highly entrepreneurial ethos. Its frontline sales reps had more leeway and authority to get deals done and celebrated great performance more exuberantly.

• The other company was more low-key and measured. Roles were better defined, corporate oversight was greater, and employees regarded their merger partners as a bit brash.

The companies had different approaches to staff compensation and performance reviews, so directly comparing the sales records of reps was impossible.

Yet common ground emerged. Over the course of several meetings among sales leaders from both companies after deal announcement, the business objectives and goals of a larger, more powerful combined sales force emerged. The leaders agreed on a new selling model – for instance, the larger combined sales force could focus more intensely on physicians in offices, while maintaining the traditional focus on hospitals.

The meetings used a technology that monitors audience responses in real time to help each side understand the other’s culture, which proved critical in determining how to unite the two teams. These cultural awareness sessions also helped the leaders work with sales reps and managers from both compa- nies to retain the swagger while strengthening oversight.

Special clean teams examined both companies’ current and projected sales data to see how effective the merged entity could be. A new performance-ranking system enabled direct comparison of reps, allowing the clean teams to create a first blueprint for integration (with leadership oversight). The blueprint included a new territory structure and sales rep organization, defining who would cover which region and how the new entity would ultimately serve customers in a way that minimized disruption for them and the organization.

Meanwhile, sales leaders began planning the thorny aspects of integration, such as compensation and benefits, training require- ments, and support functions. They developed a day-by-day plan for the activities required once the merger closed. Problems that the clean teams couldn’t resolve were noted, so the combined sales teams could address them after the close.

Within three weeks of the deal’s closing, the combined company had already implemented integrated policies on field compensation, benefits, relocation, and separation. In another two weeks, executives had established the complete integrated deployment of the combined sales forces, taking the clean- team output as a starting point and refining it in workshops.

Retention offers to managers and sales reps went out quickly. A national sales meeting assembled the combined organization and helped forge a new identity and culture. Accelerated training of sales reps on the expanded product portfolio began, and plans were set to transfer relationships for each account and sales rep. In the weeks after the merger closed, a war room oversaw the sales integration process, tracking sales and customer service performance, monitoring competitors, and following the attrition or competitive poaching of sales reps.

The process wasn’t easy. The pace of sales integration meant that key personnel from both companies did double or even triple duty, and the risk of burnout required constant monitoring. While the combined organization’s leaders communicated and shared constant feedback, cultural differences and the sometimes bruised egos of sales reps had to be addressed and decisions made rapidly. Customers had to be kept informed about the progress of the effort to feel they had an investment in it, and sales reps needed quick wins to feel that the merger was paying off and to maintain sales momentum.

The net result of all this activity was reduction in many of the risks usually associated with integrating sales forces. Uncertainty among reps about the merger’s impact on them declined, making overtures from competitors less appealing and ensuring that top sales talent remained – competitors don’t try to poach also-rans. Effective communication mitigated customer uncertainty, and the aggressive deadline set an end date for the upheaval. Quick sales wins, coupled with an expanded product portfolio and greater coverage, proved the logic of the deal to employees and customers, minimizing the risk that they would see it as a mistake. The effort met the president’s deadline: eight weeks after the merger closed, an integrated sales force was in place, with one face to the customer, and the combined company’s revenue growth accelerated.

Assessing cultural compatibility: A McKinsey perspective on getting practical about culture in M&A

By Oliver Engert, Neel Gandhi, William Schaninger, & Jocelyn So

Executives know instinctively that corporate culture matters in capturing value from M&A. In a recent survey by McKinsey and the Conference Board, 50 percent said that “cultural fit” lies at the heart of a value-enhancing merger, and 25 percent called its absence the key reason a merger had failed. But 80 percent also admitted that culture is hard to define.

Therein lies the rub. How can you address cultural problems, if you don’t know what you’re trying to fix? Hardly surprising then, that most executives feel more comfortable dealing with costs and synergies than culture, despite the potential of culture to enhance or destroy merger value.

In addition, CEOs all too often return from the deal table convinced that the companies’ cultures are similar and will be easy to combine. They miss the opportunity to use the merger as a catalyst to shift culture – both in the new organization and the acquiring company.

McKinsey has proprietary tools that split culture into specific, measurable components and link those components to more than 100 actions management can take to mitigate cultural risks. Most importantly, companies can apply a version of this tool outside-in, before even announcing a deal.

A practical approach to culture

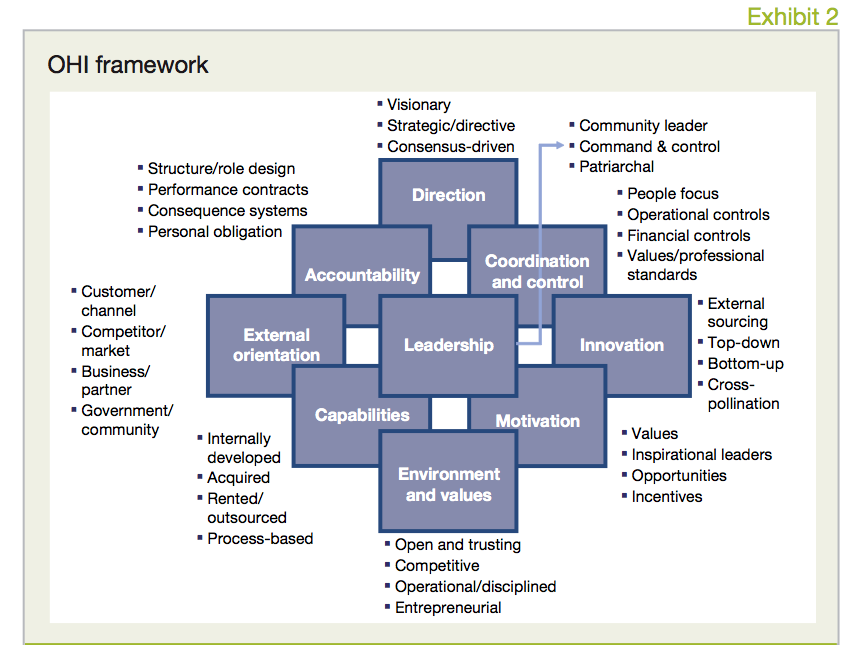

At McKinsey, we take a practical approach to understanding and tackling cultural issues. Rather than thinking about norms, rites, or employee satisfaction – terms commonly used to discuss culture – we urge executives to focus on management practices: “the way we do things around here.”

A company’s leadership style, the extent to which it holds employees accountable for their performance, its approach to innovation or building and maintaining external relationships – these are the management choices that define an organization’s culture and shape its performance. Merging companies that have incompatible cultures because their management practices drive conflicting behaviors risk loss of the best performers, a messy and prolonged integration period, and, ultimately, failure to capture merger value and synergies.

Viewing culture as the result of certain management practices makes it tangible and actionable. Merging companies can readily assess their cultural differences and find ways to address them, thanks to tools that make cultural due diligence as central to the merger process as financial and legal checklists. This high-level assessment can happen during the deal process, giving executives time to design the merger in a way that builds on cultural assets and mitigates the risks of cultural clash. (The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Sophie Birshan, Kameron Kordestani, and Sunil Rayan to this article)

Scientific assessment

Many approaches to assessing and addressing cultural issues are flawed. Many rely on leaders’ instincts. McKinsey research shows that managers in about 50 percent of merging companies read their organization’s culture very differently than other employees do, typically exaggerating the significance of their own leadership style.

Many CEOs of merging firms believe the integration will be relatively easy just because they get on well personally. They underestimate the challenges that different management practices create for most employees.

Other approaches rely on focus groups and employee satisfaction surveys, but these can prove inadequate. Although they can locate conflicting behaviors and may make people feel better for awhile, they cannot reveal the root causes of the behaviors and so do not provide insights into what management can do about them.

Thorough organizational surveys, like McKinsey’s Organizational Health Index (OHI), deliver a more robust diagnosis.

The OHI produces detailed, quantitative analysis of company performance in nine broad management practices, enabling statistically significant comparisons between companies that establish their cultural compatibility.

Such a rigorous survey requires substantial commitment of time and organizational resources. It also requires access to employees of both the target and the acquirer at a time when they may be feeling anxious or when the absence of public knowledge of the deal makes access impossible. So the question becomes, how can you measure cultural compatibility accurately without a full survey?

The answer is, an outside-in analysis that relies on relevant markers. This analysis uses publicly available information to assess the management of both companies. It can happen before the deal, remain confidential, take less than a week to complete, and does not require access to the target.

Companies signal their management approach to the outside world in many ways: corporate websites, annual reports, speeches, news articles, blogs, stock market filings, recruiting, and mission statements, to name a few. All of this is potential fodder for an outside-in analysis, providing a basis for building a company profile that mimics the results of a full survey. While it cannot match the analytical depth of a full survey, it makes an effective and accurate barometer of company culture.

McKinsey teams have conducted more than 20 outside-in assessments of merging companies where they had no prior knowledge. Many of these companies had already done full OHI surveys. The teams identified the same major areas of potential cultural friction that the OHI survey had found and that later became real issues in the merger process.

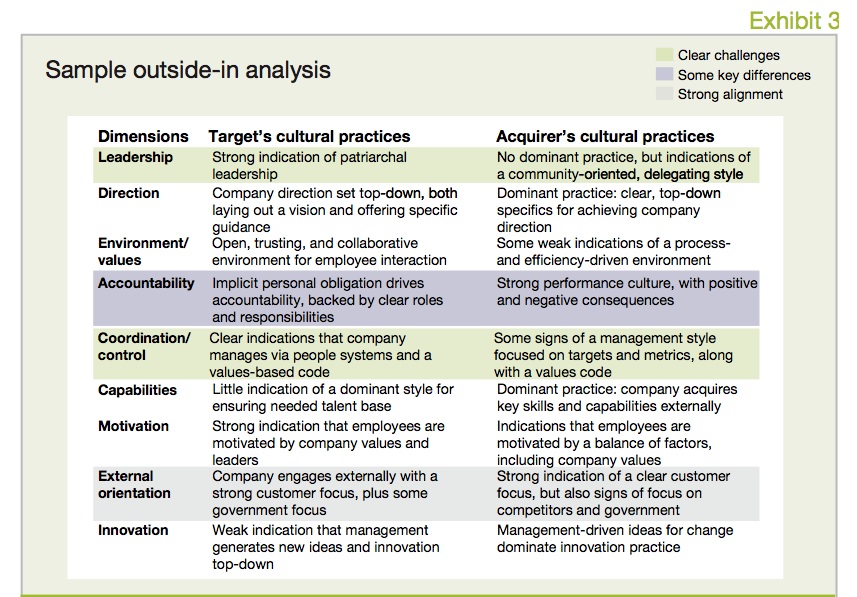

To see how an outside-in analysis works, consider the recent merger of two consumer companies. The analysis revealed clear cultural challenges in leadership and coordination/control, potential conflict in accountability, and strong cultural alignment in external orientation.

The analysis showed that:

• Company A had a patriarchal leadership style, driven by the owners and managers of this old, family-run business. Employees looked to the owners for vision and leadership and felt an emotional stake in the company.

• Company B, the acquirer, had a more “community” leadership style. The small corporate center was relatively hands-off, delegating authority and avoiding personality cults built around leaders.

With the former owners of Company A no longer involved, the merged entity risked Company A employees distrusting the new leadership and feeling uncertain about who would provide direction. The merger needed appropriate “interventions” to sustain employee motivation, especially among former employees of Company A, and organizational momentum.

Analysis of management practices around coordination/control and accountability found that Company A lacked the strong performance measurement systems of the acquirer, relying instead on employees’ sense of duty and loyalty. This potential cultural conflict cut both ways.

• Company A employees might resist strict measurement, perceiving a loss of personal involvement in a company that only cared about “making the numbers.”

• Company B employees might feel disgruntled if the performance management system became less robust and, in their minds, unfair.

This conflict might lower productivity and lose the most valued employees.

The analysis also revealed an opportunity in the way both companies thought about and managed external stakeholders. Both had a strong customer focus that could support integration and value creation. Employees from both companies were likely to respond well to the idea that the merger benefitted customers, and building cross-functional integration teams around customers could integrate and motivate all employees.

Intervention

With accurate data on cultural compatibility, what action should leaders take? In extreme cases, they might cancel the deal, as two industrial transportation companies did recently. The acquirer understood that the incompatibility posed too great an obstacle to performance and pursued other opportunities.

The outcome of a compatibility assessment is usually less dire and informs planning of a targeted approach to changing the management practices that produce cultural conflict. The leaders of the merging companies have two intervention options: standard integration interventions and tailored cultural interventions.

Standard integration interventions apply in any merger. They tend to focus on integration structure and alignment of the top team on “the way we do things around here.” How leaders handle these interventions influences the organization’s culture because their actions demonstrate strong cultural intent.

Take organizational design, for example.

• A broadly inclusive process, where senior management just provides design principles and multiple management levels develop the design, signals consensus-oriented leadership.

• A top-down process, where senior leaders design the entire organization with little input from others, signals a command-and-control leadership culture.

Talent assessment and selection offers another example. The criteria used – hard performance metrics or more subjective metrics like employee willingness to collaborate with colleagues – shape the organization’s culture going forward.

No culture is “right,” and different choices fit different circumstances. But choices must apply consistently so aligning the top team around cultural choices is a critical standard integration intervention. Unless senior leaders are excellent role models, the rest of the organization will not internalize the change.

Tailored cultural interventions address the specific findings of the outside-in analysis and focus on changing targeted behaviors. Many organizational actions can influence each fundamental element of culture. For example, more than a dozen interventions can affect management of accountability within a company.

In the merger of the two consumer companies, where the organizational compatibility assessment flagged accountability as an issue, the acquirer (Company B) decided to bring its strong performance measurement ethos to the new company.

The creation of regional manager roles with broad decision rights and strict P&L accountability pushed accountability much lower in the organization than Company A had done, sending a clear cultural message to employees. Corporate leaders made accountability a theme in most top-team communications from the start of the integration process. And the company conducted training – for all employees, but aimed at the former employees of Company A – in how to assess performance, conduct a performance dialogue, and deliver a performance review.

In another example, two merging pharmaceutical companies discovered major differences in the impact of leadership style on decision making during integration planning. The new company embedded decision-making rights and rules in high-level governance processes and highlighted the changes to major company committees as a sign of broader cultural change.

Ultimately, such choices have far greater impact on a merged company’s culture than any number of focus groups or mission statements can achieve on their own. But whatever interventions a company chooses, leaders must make them mutually reinforcing. Otherwise, conflicting signals negate the intended impact.

Cultural interventions must also be woven into the larger integration effort. Too often companies approach culture as a separate, HR-driven integration activity. This frequently makes line employees resist cultural efforts, perceiving them as a distraction from the real, value-capture-oriented work of integration. By weaving culture into core integration activities like organization design, communications, and value capture, leaders forestall these objections.

Thinking about cultural conflicts and opportunities in terms of management practices makes culture easier to define, identify, and tackle. Managers should avail themselves of tools that can help perform these tasks, whether an outside-in analysis that surfaces cultural issues even before deal close or a more thorough, fine-tuned OHI survey.

These tools offer a systematic way to diagnose and address cultural issues in a merger. Every integration action, from announcement to combination, has impact on corporate culture and therefore value. Executives need to understand the cultural compatibility of companies planning to merge as early as possible.

Opening the Aperture 3: A McKinsey perspective on finding and prioritizing synergies

By Oliver Engert, Eileen Kelly, & Rob Rosiello

Best-practice companies explore the full range of opportunities to achieve maximum value from every merger. They take the broad view mapped in the McKinsey framework to identify, quantify, prioritize, and capture synergies and value.

But these companies also realize that opportunities to create value differ by deal type, and they tailor their search for synergies accordingly.

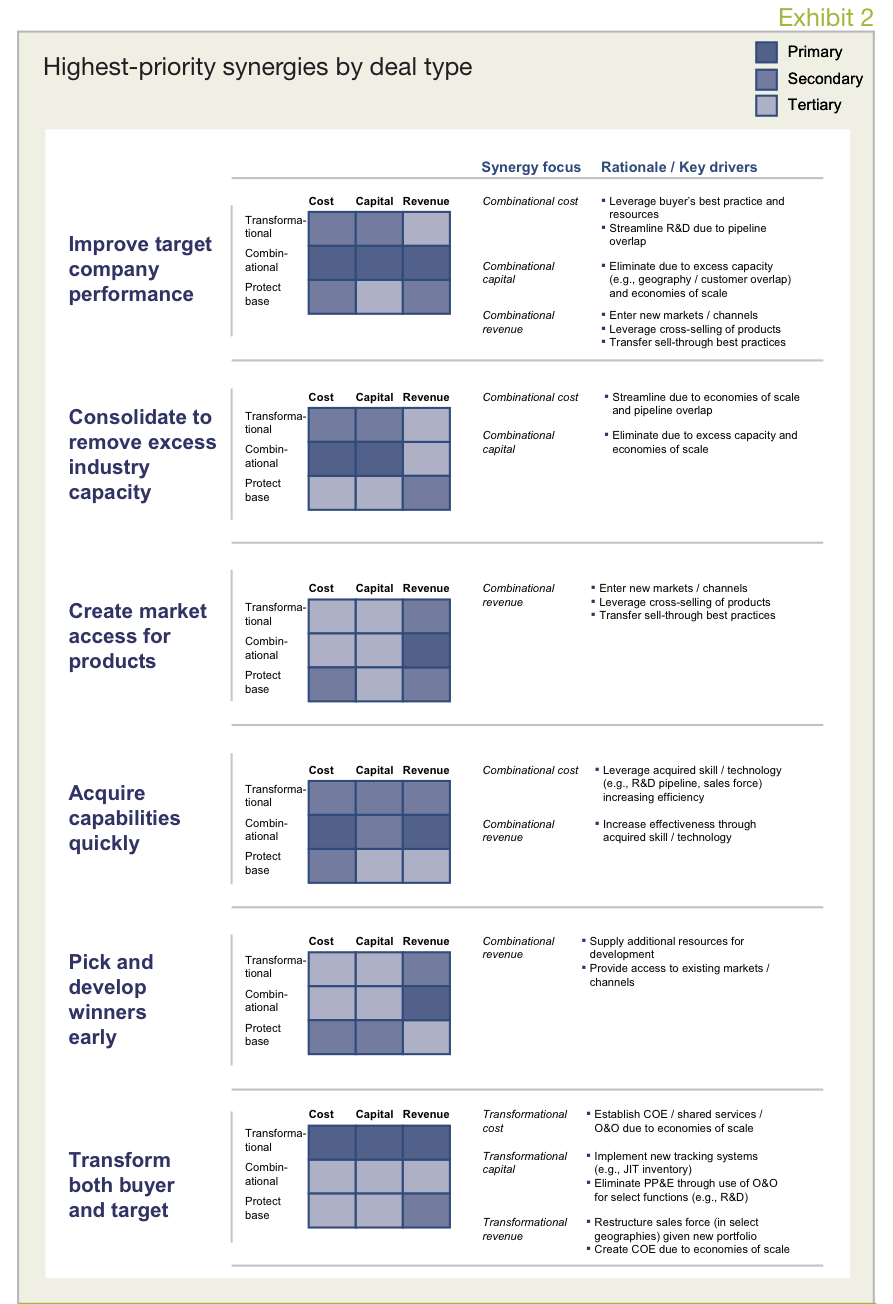

Six deal types and their opportunities to create value

McKinsey has identified six deal types. Each requires asking different questions to locate their most likely synergies:

• Improve target company performance. The buyer leverages their superior capabilities to improve the target’s operations.

– What superior capabilities does the buyer possess?

– How can the buyer transfer these capabilities to the target?

• Consolidate to remove excess industry capacity. The combined company rationalizes commercialization to increase efficiency, prioritizes initiatives (e.g., R&D efforts), leverages economies of scale (e.g., back office consolidation), and cuts duplicative overhead.

– Where is there excess overlap in the operating model?

• Create market access for products. The combined company uses its existing capabilities and capacity to sell through to new markets or geographies more effectively.

– What market entry advantages does the buyer or the target have (e.g., channel access)?

– How would additional resources affect sales?

• Acquire capabilities or technologies quickly. The buyer leverages the target’s capabilities, gaining access to skills or technologies more quickly than it could in-house.

– What skills or technologies does the target have?

– How can the buyer leverage these capabilities?

• Pick and develop winners early. The buyer provides resources to promising targets.

– What does the target need to succeed? What are the risks?

– What capabilities does the buyer have that can help the target succeed?

• Transform both buyer and target. An industry-changing deal transforms the combined company into a superior company.

– How much transformation is the buyer willing to undertake?

– Which specific opportunities would create transformation?

– What specific challenges could disrupt business during the transformation?

Unfortunately, many companies, and industries, look only to their traditional deal types, which they know how to pursue, and they leave money on the table as a result. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, typically merge for industry consolidation or quick acquisition of capabilities or technologies. Opening the aperture and exploring less traditional transformational deals could uncover additional opportunities to create value.

The highest-priority synergy opportunities by deal type

To encourage broader thinking, McKinsey has mapped synergy opportunities by deal type. The chart shows the most likely, and therefore highest-priority, synergies in each type of deal. Not surprisingly, opportunities in the combinational category of value creation are most common, but their focus extends well beyond cost.

Of course, any company contemplating a merger should explore all its synergy opportunities, but the mapping can provide a sound starting point for prioritization.

As companies look to mergers for benefits beyond scale or cost reduction, they need to consider a broader range of opportunities – more types of deals and more sources of synergies. The McKinsey mapping can help them weigh and balance opportunities to create maximum value from a merger.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter