Publications Not So Fast: Companies Need To Pace Themselves During The Integration Process

- Publications

Not So Fast: Companies Need To Pace Themselves During The Integration Process

- Bea

SHARE:

By Gillis Jonk and Michael Ungerath – A.T. Kearney

Prevailing wisdom says speed in a merger or acquisition is essential to success. Integrate quickly or fail. So why do only a few generate real value? Depending on who you talk to, fewer than 20 to 50 percent of M&As succeed. It’s time to rethink our philosophy on merger integration. Speed, unless pursued selectively, may be less an element of success and more a fatal flaw.

Corporate marriages are still vying for headline space. Bank of America and MBNA. Molson and Coors. Procter & Gamble and Gillette. They’re not only competing with each other, they’re up against the legacy of past mergers. HP fires Carly Fiorina in part for failing to integrate HP and Compaq. And although DaimlerChrysler appears to be on the right track, its stock price rallies still put it at just half its pre-merger value. Wherever you are in the headlines, mergers are a risky business.

With a continuing wave of mergers, everyone agrees that success rests with a speedy integration. Weren’t HP’s problems due to miserably slow information technology integration? Isn’t the first task of merger integration to reconcile divergent operating philosophies? Isn’t there a universal threshold of 100 days?

Moving too quickly in some areas can be just as hazardous as moving too slowly.

Such questions, though over-simplifications, do highlight a key issue. In merger integration, speed counts. But what exactly is merger integration speed and how does it influence integration success? Through research and discussions with executives involved in merger integration efforts, we have developed a nuanced view of speed. We believe that to achieve a successful merger integration, companies should avoid the temptation to emphasise outright speed. Instead, they should look to a set of strategic understandings of speed that center on the following pillars:

There is no absolute merger integration speed. Companies should measure integration speed – and resulting benefits – against the average rate at which the industry as a whole captures integration benefits. Using this measure will help companies not only choose the best merger integration speed but the appropriate mix between acquisition growth and organic growth.

Integration speed requires a selective perspective. Some functions are simply more important to integrate than others – and importance should be defined not by savings potential but by what drives competitive advantage. Understanding the value of these functions and prioritising them can greatly enhance integration success.

Integration can proceed at its own speed – recognise the differences. When you force all parts of the company to march in lockstep, you risk doing more harm than good. Different parts of the company should have a different integration timetable based on their needs. By allowing each part to pursue consolidation and integration at its own speed, or not at all, you unlock greater potential, creating a richer, more value-creating merger.

Of course, outright speed should still drive many aspects of merger integration. Success in ensuring organisational stability, minimising customer defections and meeting regulatory requirements relies heavily on quick, decisive actions. However, as we explore in this article, moving too quickly in some areas can be just as hazardous as moving too slowly.

Speed is relative

The rate of real merger success – expressed in shareholder returns that exceed the peer group – is the subject of much research. And the results are invariably disturbing. Most studies agree that less than 50 percent of mergers succeed; only 20 percent of mergers have unequivocally created value. While such results certainly warrant a thorough examination of how to improve merger integration, they can also be approached in a different way.

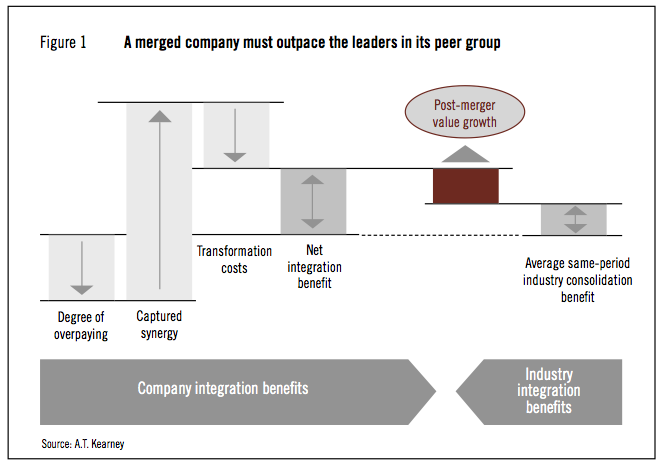

How do mergers create value? To understand how, let’s focus on how mergers improve competitive advantage and ignore for the moment how mergers create financial or market benefits. As Figure 1 illustrates, the starting point is obviously the price paid for the acquired company; a buyer that overpays will have to find compensation in some way. Compensation comes from synergy: the merger creates value through both commercial and operational synergies, minus the one-time transformation costs. So the net integration benefit represents the value created, right? Not exactly.

To properly measure the value of the merger, you must also take into account the average merger integration benefit rate for the entire peer group over the same time period. The true value of the merger is the difference between the two (the red box). In other words, if everybody else achieves the same (relative) merger integration benefits as you, then competitively speaking you’re still at the same level you were before the merger or acquisition. In this context, it’s no wonder only half of all mergers create value when measured against their peer group – those are the half that are above average. The other half performed below average. What else could we expect?

So to create better-than-average value, a merged company must outpace the leaders in its peer group in capturing integration benefits. Unfortunately, this also means that if you keep step with the overall pace of industry consolidation and achieve decent merger synergies, you’re not doing enough. This will merely keep you on par in terms of creating value. And assuming your peers do an acceptable job, the risk is high for falling behind the pack. Failing to capture a few merger synergies, or spending too much to achieve them (for instance, being distracted for too long from serving customers) is all it takes to become one of the negative statistics.

When it comes to merger integration strategies, understanding your industry consolidation ‘clock speed’ – the pace at which consolidation and integration is taking place – is critical. The industry pace will help determine your position relative to acquiring new companies, integrating previous acquisitions, growing organically and increasing competitiveness through business improvements. If you overdo it on the merger and acquisition front, you risk overstepping your company’s ability to consume the acquired companies or incurring excessive transformation costs that drag down business improvement and organic growth. On the other hand, being too passive with M&A activity could result in falling behind the industry average. After all, we can say that 50 percent of mergers fail and we have the data to prove it – but 50 percent of all companies, including those that don’t merge, fall below the median. If we could measure it, we would surely find that 50 percent of decisions not to merge also turn out to be wrong.

As industries pass through their consolidation life cycles, companies will face a different set of merger integration priorities. In the early stages, in which leading players get big quickly in order to stay in the game, the goal of merger integration is to get ready to acquire the next company. For example, during the 1990s, Cisco Systems acquired companies almost on a weekly basis. Cisco postponed full integration, which would have been too disruptive, preventing the company from focusing on its next acquisition. Instead, it established business control, included the acquired company’s offering into its own offering, minimised the business risks, and moved on.

A mix of acquisitive growth and organic growth should always be part of a growth strategy as long as it is industry specific.

Did that represent a failure of merger integration? Hardly. It was a strategic choice to postpone the more profound integration until a time when it could be handled more effectively. Cisco decided to postpone integration because the industry clock speed dictated the need to grow quickly through acquisitions. In such environments, integration strategies should focus on how the company can increase competitiveness the most with the least effort.

During later stages of the consolidation life cycle, however, industry clock speed changes and so must your strategy. Gaining the real benefits of a merger at this point requires more truly integrating the many different parts of the merging companies. As more mature companies find their core activities, merger integration requires divesting and outsourcing those activities that are non-core. Once we appreciate this relativity – that speed can mean different things in different industries or different times – it’s easy to also apply it internally.

At this point, a question often arises about how industry-leading companies that predominantly grow organically – such as WalMart in North America, or Toyota in the global automotive industry – fit into the consolidation picture. Because their growth has very little to do with acquisitions, they cannot be considered among traditional consolidators of their industry. Or can they? As these leaders grow organically, they manage to increase the combined market share of the top three or five players in their industry, which we know is the typical measure for industry concentration. At the same time, as their revenue increases, they are in a better position to leverage their business infrastructures, brands and channel positions – really, to leverage their entire supply chains. In fact, through organic growth, these companies enjoy the same sorts of benefits that merging companies enjoy through synergies. Apparently such benefits can be obtained either by investing in organic growth or by acquiring other companies and investing in the integration. Therefore, a mix of acquisitive growth and organic growth should always be part of a growth strategy as long as it is industry specific.

When it comes to speed, be selective

Merger integration does not happen in a vacuum. As we just noted, it happens within industry dynamics that dictate your company’s growth strategy. But too many companies look at merger integration activities in isolation. They are prioritised based on top-line or bottom-line merger synergies, period. Instead, we need to ask: how can integration efforts contribute to organic growth? How can they aid the overall competitiveness of the business? Merger integration is not a stand-alone riddle to solve. It needs to be an integral part of your overall business strategy.

By taking an overall strategic perspective, you’re able to define speed in relation to your company’s long-term competitiveness, rather than capital markets’ hunger for proof of short-term success. Not all merger integration efforts are equally important, nor do they deserve the same rigor or attention. Resources should be allocated to aspects of integration that contribute to competitiveness, such as brand equity and innovation.

Consider the global brewing industry. Major players such as Heineken, Inbev and SABMiller have gone through a hectic M&A phase of acquiring strings of smaller brewing companies. Most have been selective in their merger integration efforts. For example, Heineken has focused on injecting its global premium brands Heineken and Amstel into new markets through its acquisitions. It has a well-oiled brewing machine set up in Zoetermeer, the Netherlands, and a capable international organisation. So after acquiring a company, Heineken sought to establish effective business control and align commercial operations in potentially overlapping geographic regions. But it didn’t spend much effort on truly integrating the different local brewing activities into a single efficient machine – a time-consuming task. Instead, it took the quicker route of bringing best practices and brewing competencies to the various local brewers. The result was to create value quickly and effectively.

Heineken’s story has some obvious lessons for the merger of P&G and Gillette. When two strong branded companies merge, they need to assess how to leverage their most valuable parts – their brand equity and distribution – as quickly as possible, for example, by using each others’ products and brands in specific geographic regions. Another benefit might be to use each other’s supply chains so as to provide more options to retailers without heavy investments. Also, being able to tap into each others’ innovation pipelines can give a welcome boost to the overall process. But the point is, each of these merger integration projects – as well as several others that the merged company should probably postpone – has its own speed, and the merged company needs to be selective about which ones to invest in.

Does the Heineken story apply also to the now-consummated Molson Coors merger? Not necessarily. Heineken’s successful strategy was built on its unique competitive advantage: the tremendous worldwide brand strength of the Heineken and Amstel labels. The Molson and Coors brands lack that global strength. Furthermore, Heineken executed this strategy during a period when the industry was in a scale-up phase, when its clock speed involved the rapid acquisition of smaller targets. The Molson Coors deal, advertised as a ‘merger of equals’ (although, to us there is no such thing) highlights the industry’s entry into the next phase of its consolidation life cycle. With fewer small acquisition targets available, growth strategies – and thus merger integration speed and priorities – are changing. Molson Coors must do a more complete operational integration, streamlining the infrastructures of its 18 breweries, finding both cost savings and organic growth opportunities. For that matter, Heineken must soon do the same: complete the more comprehensive integration of its new acquisitions to maximise their potential value. It will need to look fully into all strategic and operational merger integration activities. Indeed, no longer solely betting on quick acquisitions, Heineken is now looking to set up new brewing operations in China.

Setting priorities

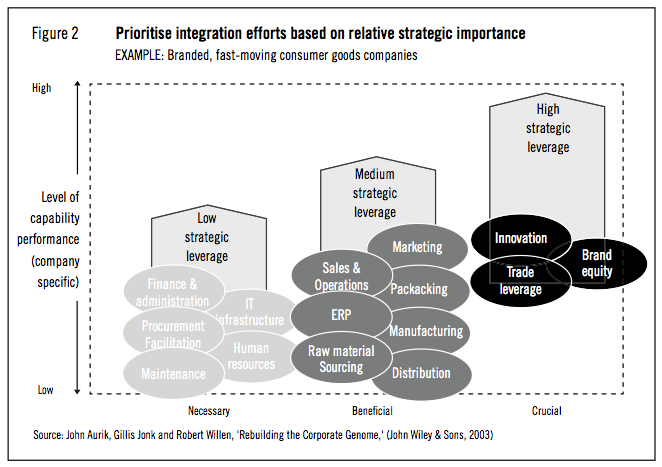

Selective speed suggests that you can set priorities for merger integration. But how do you set these priorities? The answer may be surprising: It’s not the relative size of the different merger benefits – or even the relative ease of achieving them – it’s competitive advantage. If your goal is to achieve overall business success, your priorities must come from your overall business strategy. And of course your overall business strategy is based on maximising competitive advantage.

You have to effectively translate strategic priorities into specific requirements for the different parts of the company’s business, and then ask to what extent integration – as opposed to business optimisation – contributes to achieving these requirements. Then, and only then, can you evaluate this contribution against the potential synergy benefits (and required efforts to gain them) of integration (see Figure 2). The result: certain integration efforts are postponed even though they represent cost savings—because they aren’t key drivers of competitive advantage.

Seems obvious. Surely companies consider strategic objectives in planning integration. Sadly, however, there is often a strong disconnect between pre-merger strategic intent and post-merger management of hundreds of integration projects under the speed-obsessed eye of capital markets.

Sadly there is often a strong disconnect between pre-merger strategic intent and post-merger management of hundreds of integration projects under the speed-obsessed eye of capital markets.

For example, P&G and Gillette seem to have a sound strategic intent: layering their categories to achieve market power. Because they produce different products, there’s no need to alter their manufacturing footprints. They can follow the lead of P&G’s successful 1999 integration of pet-food maker Iams: The company focused on introducing Iams’ products into its competitive advantage in sales and distribution. Meanwhile, cost-cutting synergies were delayed: They waited more than four years to convert Iams’ computer platform. P&G “purposely delayed some changes to avoid taking employees’ eyes off the ball,” explained Iams spokesperson Kelly Vanasse in an interview with the Cincinnati Post.

But P&G’s acquisition of Gillette has a higher profile. With more scrutiny, will P&G be able to withstand capital markets’ pressure to demonstrate across-the-board synergies? Even more pressure has been exerted on the retail marriage of Sears and Kmart, where the predicted synergies in operating costs ($300m a year) outweigh the predicted cross-merchandising opportunities ($200m a year). With such a huge focus on cost cutting, will the new company be able to keep its eye on competitive advantage, and the value of applying merger integration speed selectively?

Actually, the discussions of what exactly comprise the most valuable assets of the new Sears Holdings suggests a third, often overlooked, dimension of merger integration speed – speed differentials.

Recognise the differences

Companies are still stuck in their merger-as-compromise mindset – like the car owner who decides to maximise his assets by welding together a Corvette and a Neon. Often, the merger seeks to integrate two entire companies, rather than individual parts. But if different parts of the value chain have different characteristics, then obviously speed cannot mean the same thing for all. And when two companies merge, they need to think about such ‘differences’ in making their choices.

As an example, consider Handspring’s 2003 acquisition of its main rival Palm Computing, inventor of the handheld computer. At the time, the handheld market in general had lost its momentum and was losing market share to smart phones (cell phones with sufficient power to double as handhelds). The merged company needed to act.

The acquisition could have created one big troubled company in a declining market, and no amount of success at traditional notions of integration could have saved it. Instead, the acquisition created two companies: PalmOne makes hardware; PalmSource makes its operating software. The trigger for the split was that the software powers not just handhelds but also smart phones, including those made by PalmOne’s rivals.

Shareholders saw the opportunity to let the software portion pursue its own speed differential. By going its own way, PalmSource could focus on growing the operating-software business independent of hardware. Handhelds may eventually die out, PalmOne may or may not eventually transition to manufacturing smart phones – but PalmSource is no longer tied down by these dynamics. It can sell software to anybody.

The result: PalmSource has expanded into handsets (the ‘non-smart’ kind of mobile phones). It expanded its geographic reach into China, aided by the acquisition of a company called China MobileSoft. And it’s using the China MobileSoft platform to expand its technology to Linux. PalmSource believes that not only will Linux reduce development costs, but it will serve as a base to expand to software for new products such as embedded devices, appliances and consumer electronics.

What if HP and Compaq had used this sort of reasoning to drive their merger? They could have merged into not one large company, but five different ones:

1. An information technology services business. Standing alone, this company could have pursued customers for its services regardless of the make of hardware. (IBM has allowed its IT services business to do the same thing.)

2. A personal computer manufacturing business. Again, standing alone it can sell to anybody. And again, IBM is doing the same thing, selling its PC manufacturing business to the Chinese PC maker Lenovo Group.

3. A printer manufacturing business, or indeed all non-PC hardware manufacturing. HP already sells printer components to other manufacturers. Why not let this segment pursue its own fate?

4. An HP-branded sales business, selling PCs, printers and handhelds to consumers. This business would capitalise on the HP brand, but source its hardware needs from the best supplier rather than being tied to an in-house supplier.

5. A Compaq-branded sales business with the same philosophy but also selling servers, operating systems and services to corporate customers.

Radical? Sure. And it won’t work everywhere. Breaking up corporate value chains is never easy, and requires a great deal of strategic planning. You need to consider not only the consolidation characteristics of different parts of the value chain, but also the degrees of freedom for separate consolidation. In other words, you need to ask whether the segment can in fact be separated by evaluating the effort of maintaining an additional business, factoring in the valuation implications (for publicly listed companies), and judging the short- and long-term risks to the main business.

A more nuanced view

The nuances of merger integration speed highlight the need for companies to strategically prioritise when planning a merger or acquisition.

When you understand these different types of speed, you can apply the right growth mix, adopt the appropriate selective speed, and tailor separate M&A strategies for individual parts of the business.

This new view leaves plenty of conventional wisdom intact. It is still necessary to have effective program control and track benefits, to provide organisational clarity early on, and to accommodate cultural sensitivities. But the new view does change the focus of integration efforts – whether triggered by an acquisition or a delayed merger transformation – by placing the emphasis firmly onto the company’s growth agenda.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter