Publications Mergers In A Low-Oil-Price Environment: Proceed With Caution

- Publications

Mergers In A Low-Oil-Price Environment: Proceed With Caution

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Bob Evans, Scott Nyquist, Kassia Yanosek– McKinsey & Company

Contributors: Kelly Hsu, Hyder Kazimi, Parker Meeks, Kabir Melwani, Joe Quoyeser, Matt Rogers, Paul Sheng

A deal deluge typically follows an oil-price collapse — but hasn’t always created value. Past cycles teach that deals enabling players to lower costs will probably be most valuable in today’s volatile oil-price world.

Unlike what happened during previous oil-price collapses, M&A activity has been limited since prices started to fall in 2014. But the signs are that M&A activity may be building, and oil-company management teams should think about what deal strategies they should pursue. The oil-price trend has historically been one of the most important determinants of how value is created in the oil and gas industry, and some M&A strategies that worked in the rising-price environment over the past 15 years may not work in today’s market. In this article, we look at the industry’s M&A performance across cycles back to 1986 and identify strategies that could help oil and gas companies create value through the price trough, measured by total returns to shareholders (TRS).

The next M&A wave may be starting to break

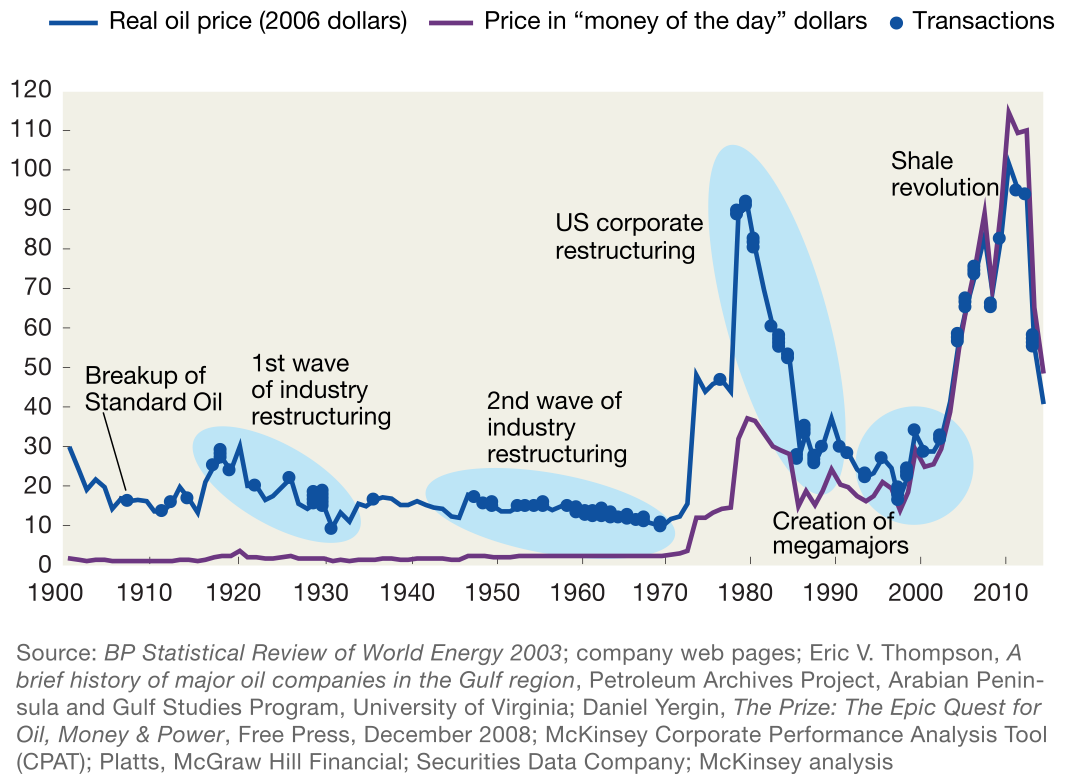

Most commodity industries are prone to consolidation during the downside of the cycle, when supply surpluses accumulate, prices fall, and competition heats up. The oil and gas industry is no exception (Exhibit 1). In the 1998–2000 price trough, more than 25 deals greater than $1 billion in value were executed in North America alone, including the BP–Amoco, Exxon–Mobil, and Chevron–Texaco megamergers. In total, this wave of deal making amounted to more than $350 billion in just over two years. It took another decade to match the same amount of deal volume in North American exploration and production (E&P).

Oil prices are recovering a bit from a 12-year low in January (below $30 a barrel) but remain well under the levels of most of the past decade. There are signs of rising M&A activity, even though few deals have been executed so far. Over the past year, bid–ask spreads have been too wide for deals to proceed. However, this could change, given the increasing signs of vulnerability among the weaker players in the market.

First, industry-wide leverage has risen significantly over the past three years, and it is particularly high for independent E&P companies with exposure to US shale production. This group’s leverage has spiked—with debt at nearly ten times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization—indicating an increasing likelihood of restructuring for the most indebted players. Second, pricing hedges are beginning to come off. As a result, it is possible that there will be oil and gas companies available at distress prices, either because they are in Chapter 11 (continuing to operate while restructuring their debt) or because their market valuations will sink to such low levels that they could be attractive acquisition candidates, even if the buyer has to reach agreement with their bond holders as part of the deal.

Exhibit 1. Historically, oil price down cycles have led to an increase in M&A activity.

It’s not easy to create value through M&A in the oil industry

Companies will clearly want to be on the lookout for how to use this time of transition to strengthen their competitive position through M&A. Successful oil and gas M&A obeys many of the same rules that should prevail in any other industry, beginning with not overpaying. But oil-price volatility adds a unique element to the mix. Oil-price levels have a powerful influence on most aspects of the industry’s performance, as the profitability figures of the past year make clear, and M&A performance is no exception. The industry therefore should be careful about the lessons it takes from its M&A experience during the period of rising and high oil prices in the nearly 15 years to 2014.

This view is supported by research we have undertaken on E&P M&A in the United States over the past 30 years. The research segmented deals into the four themes that characterize most deal activity—megamergers, increasing basin or regional density, entering new geographies, and entering new resource types. We contrasted the value- creation performance of the deal themes under the two main pricing environments in force during the period: low prices from 1986 to 1998 and rising prices from 1998 to 2014 (with the exception of 2008 to 2009). (For a more detailed discussion of the methodology, see the sidebar, “Keeping track of value creation through oil and gas M&A in the United States since 1986.”)

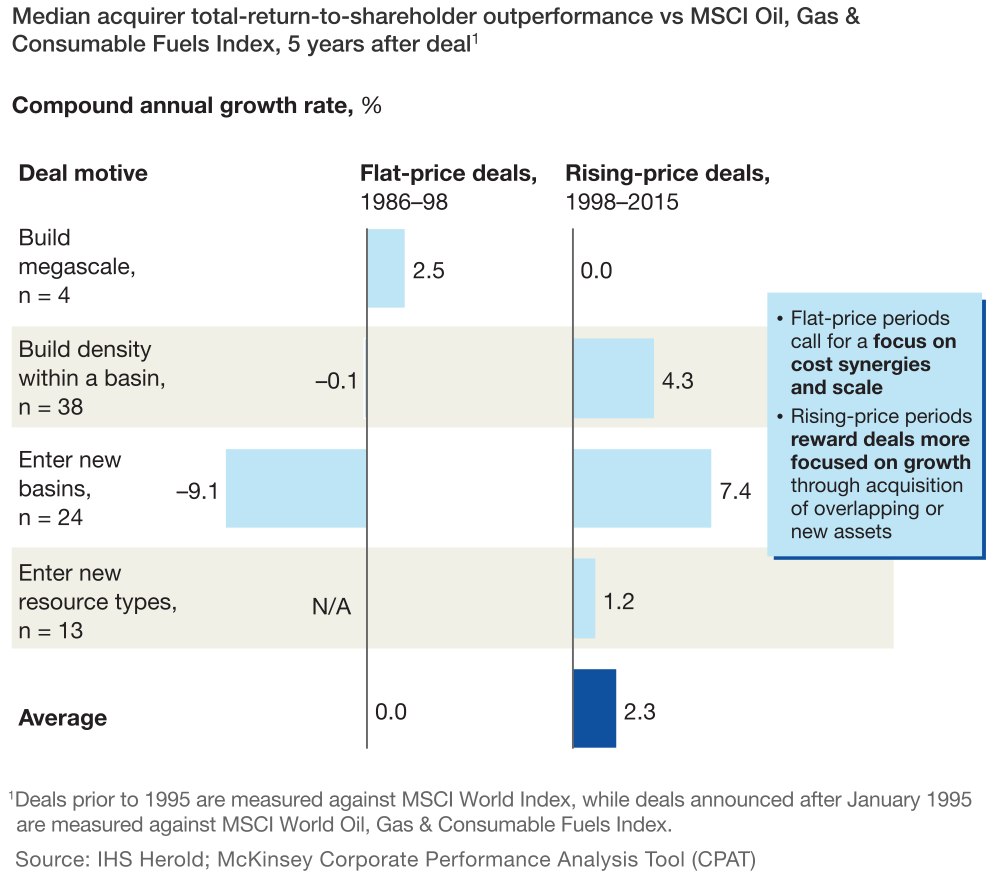

There have certainly been a number of successful deals struck throughout the period. But the research shows that on balance, the oil and gas industry’s ability to create value from M&A has been mixed, and that value creation is particularly challenging when deals are struck during oil-price down cycles (Exhibit 2). Of all the deals evaluated for the 1986–98 period, only megadeals outperformed their market index five years after announcement. Periods of flat prices appear to call for a focus on cost synergies and scale. In contrast, in the 1998–2014 period, when prices were generally rising, more than 60 percent of all deal types outperformed their market index five years after announcement. Not surprisingly, this kind of rising-price environment rewarded deals more focused on growth through acquisitions of overlapping or new assets. However, with prices at low levels again, this historical perspective suggests we are back in less-favorable territory for value creation through M&A.

Exhibit 2. Buyer beware if we return to a 1990s steady state of flatter oil prices, although basin-building deals appear to be the lower-risk option.

What the historical data show about value-creating moves

Since deal strategies that may have been successful over the past 15 years of rising prices may not be successful in a “lower for longer” oil-price world, what pointers do the historical data provide about which M&A strategies might be robust under all pricing scenarios, including today’s depressed pricing environment?

It’s useful to go back to basics on how value is created in the oil and gas industry, and M&A’s role in it. In periods of a strong market and rising oil prices, growth is the dominant driver of value creation. However, in flat or depressed oil and gas markets, growth is fundamentally challenged. Improvements to returns on invested capital (ROIC), including cost reductions and raising capital efficiency, are usually more effective approaches to unlocking value. Our research on upstream North American companies bears this out: the data show a strong correlation between total returns to shareholders and ROIC in the 1992–98 period, when oil prices were flat and low, and a weaker correlation after 1998, which marked the beginning of the next oil-price up cycle.

M&A in oil and gas typically creates value where it leads to reductions in costs and increases in capital efficiency, and where an acquirer brings superior insights on the value-generating potential of the purchased assets—while always in the background there is the influence of oil prices.

When we look in more detail at the historical record of the four categories of deal themes to see what insights might be applicable to future M&A strategies, we find these concepts being repeatedly validated. While any one deal may have multiple value drivers, most deals have a main theme, and this is how we’ve categorized them.

Megadeals

What underpinned the value creation achieved by the megadeals of the low-oil-price period? Large mergers have historically created value through cost reduction at the corporate, region or country, and basin levels. Acquirers captured synergies, such as overhead reductions, and optimized the combined portfolios to favor the most competitive and capital-efficient projects. This resulted in significant improvements in returns on invested capital, and that in turn translated into shareholder returns in excess of the market index. Further, the expanded breadth of the combined company’s portfolio—both geographically and in resource types—helped extend reach, which facilitated growth and diversified the risk of megaprojects. As oil prices rebounded and growth took off, this was rewarded in equity markets.

Take the merger of Exxon and Mobil, announced in 1998. Its strong focus on executing a postmerger-integration program enabled the company to capture $10 billion in synergies and efficiencies within five years, more than three times greater than the $2.8 billion savings estimated when the deal was announced. The savings resulted from job cuts and putting in place stricter, centralized controls on capital spending and allocation across the postmerger company—upstream, downstream, and technology. Over the following decade the deal opened the path for significant growth, a notable example being expansion in the liquefied-natural-gas business.

In the rising-price period, there were no megadeals to be included in our data sample. But a number of major acquisitions in the period used value-creation levers similar to those of the earlier period. For example, Anadarko Petroleum’s acquisitions in 2006 of Kerr-McGee and Western Gas Partners for $23 billion created large-scale positions in the deepwater Gulf of Mexico and Rockies, each of which provided cost-savings opportunities and growth potential. Postmerger, Anadarko made substantial divestments to strengthen its finances and improve the quality of its resulting portfolio, setting the company up for a decade of organic growth. In today’s environment, any large-scale acquisitions that do occur are likely to create the opportunity for significant cost reductions using these same levers.

Basin- and regional-density deals

The data show that deals increasing basin or regional density in a low-oil-price environment created value more or less in line with the benchmark, while in the rising-price period, these regional transactions outperformed the benchmark. In principle, such deals facilitate cost-reduction opportunities because the acquirers are already established operators in the area. They know the geography and geology, the practices, and the people (internal and external) necessary to maximize production from these assets. In addition, they can capture synergies by cutting regional overhead costs, consolidating vendor contracts within basins (where many onshore providers are regional rather than national), and optimizing overlapping operations (for example, increasing the efficiency of pumpers and other parts of the supply chain).

Chevron’s $18 billion acquisition of Unocal, in 2005, highlights characteristics of a successful deal that increased regional density. In Thailand, Chevron consolidated acreage under the Unocal manufacturing model for drilling, which enabled it to increase volumes and reduce costs significantly. In the Gulf of Mexico, acquiring Unocal put Chevron in a position to move from exploiting individual wells to integrated hub development. This enabled Chevron to make much more efficient use of its capital, reducing costs. While the acquisition was regarded in the industry as having a high deal premium, other factors that boosted value creation included Chevron’s insights on the acquired resource’s potential based on the acreage it already controlled, strong merger-management execution, and the benefit of a rising-oil-price environment.

Entering new basins

This theme entails entering new basins within a company’s existing resource type — such as a shale producer entering new North American onshore basins or a Gulf of Mexico deepwater operator expanding to foreign offshore basins. Our data show a clear contrast in performance between the two pricing environments, with the most successful deals occurring during periods of rising prices, and the most value destroying, decisively, in periods of flat or depressed prices. By nature, such deals offer few cost-reduction opportunities, as there are limited synergies in operations for the acquirer to tap. In a rising-price environment, however, a lack of cost synergies may be offset by the overall value created by higher and expanding margins coming from top-line growth. Other value-creation levers may be at play as well—for example, if the acquirer sees greater potential in a resource than its current owner does.

Examples of successful deals abound from the past 15 years—for instance, Encana’s $2.7 billion acquisition of Tom Brown, in 2004, which established its gas-production position in a number of new basins in the US Rocky Mountains and Texas. On the other hand, an example of what can go wrong during the flat-price period is Burlington’s $3 billion acquisition of Louisiana Land & Exploration, in 1997. The acquirer expanded in areas including Louisiana, the Gulf of Mexico, Wyoming, and overseas, but overpaid for mature assets, with no opportunities for synergy capture to help returns. Burlington lagged behind its index by 7 percent over the next five years, and was itself acquired in 2006.

Entering new resource types

This theme is typically a portfolio-expansion strategy, such as an onshore producer seeking to add offshore operations or a company with conventional operations entering unconventional gas and shale-oil basins. Our data set does not have examples of such deals during the period of depressed oil prices. There have been a number of value-creating deals in the rising-price period, but there are also a number of examples of companies encountering difficulties even in this environment.

Foreign companies that have entered North America to build exposure to unconventional shale assets provide mostly cautionary tales. Some of these companies lacked the expertise for local land acquisition (a competitive advantage for most high-performing shale producers) and needed to climb the learning curve to gain the capabilities to be an efficient producer. As a result, these transactions were value destroying.

By their nature, deals defined by this theme do not offer the kind of cost-reduction opportunities that can help ROIC performance in a period of low oil prices.

What are the implications for M&A strategies and practices today?

“This is the sixth downturn of my career” is a familiar refrain in our conversations with senior industry executives. However, much has changed in the industry since the last downturn, with the ranks of the major companies radically thinned, while the shale-oil boom, in combination with plentiful credit, has launched hundreds of mom-and-pop producers to create a whole new branch of the industry. A review of deals over the last cycle is necessary but not sufficient. As the industry works to find its bearings, here are five guidelines to help oil-market participants.

- Be clear on the strategy. Companies should define their rationale for M&A activity as part of their corporate strategy before focusing on deal sourcing. Investment themes should seek to achieve a strategic imperative and complement a company’s competitive edge. How does this deal fit with what you want to look like long term? How will the acquisition supplement your organic growth? Are you a “better owner” than competing buyers? Further, different themes may be appropriate for different types of players, depending on their structure, appetite for risk, and oil-price outlook. There are a number of different deal types that also may be appropriate, for example asset transactions, mergers of equals, or a series of small bolt-on acquisitions.

- Identify value through a rigorous due-diligence process. Many executives place too much emphasis on simply looking at whether a transaction is accretive or dilutive of the acquirer’s earnings per share or on basing deal value on market multiples. Instead, they should conduct a due-diligence process focused on a granular understanding of the assets’ resource potential, the target’s business model and operations, and value potential under varied market scenarios. This approach allows the acquirer to gauge the real-world viability of the operating model, including upside and downside scenarios. Are the forecast growth rates and estimates of returns on invested capital consistent with those of similar historical periods? What “black swan” scenarios should you consider? Do your pro-forma analyses consider competitiveness against other resource types?

- Focus on identifying cost and capital synergies up front. Regardless of the strategic intent underlying the deal, in today’s price environment executives should work hard to identify opportunities to cut costs and improve capital efficiency. All deals are likely to present the opportunity to create value through overhead cost reduction at the company, region, and basin and field levels. This should be a focus of the due-diligence process. What capabilities do you have that are complementary to the target? What opportunities are there to combine infrastructure within a region or basin?

- Don’t bid away the value in the deal process. Winning acquirers establish a rigorous deal process with clear decision stage gates, as well as a clear understanding of important risks or upside opportunities. This approach allows companies to avoid overpaying, forfeiting potential value. In addition, good acquirers are less likely to waste resources on deals the market previously deemed unattractive and more likely to focus solely on objective measures of value creation. Are the downside risks in the deal and the implications on valuation clear? How will that influence the approach to negotiations? Is a robust deal process in place, with clear “walk away” rules established?

- Plan postmerger integration early and execute rigorously. Winners make critical decisions about integration governance and value potential well ahead of the close. They also make beating, not just meeting, the value-creation pro-forma target results part of the postmerger plans and associated management incentives. They do all this while at the same time recognizing that oil and gas is a people business, and winning the hearts and minds of key employees at acquisition targets is essential to success. Empowering the integration-management office (IMO) to update and exceed the synergy target, and executing quickly at the start of the integration, are important factors in maximizing value creation. Putting a senior leader in charge of the integration is also an important success factor, particularly for larger transactions. Is the IMO designed to capture maximum value? Can the IMO be launched on the day the deal is announced and be completed rapidly? If the answer is no, value leakage is inevitable.

Another big wave of M&A activity in the oil and gas industry could soon break. As leading players in the sector plan their moves, they should recognize that deals offering cost-reduction opportunities are likely to create the most value in a lower-for-longer oil-price environment. At the same time, excellence in M&A practices throughout the deal process—from the identification of opportunities to postmerger integration—will remain an important contributor to value creation.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter