Publications Merger Integration: Delivering On The Promise

- Publications

Merger Integration: Delivering On The Promise

- Bea

SHARE:

By Gerry Adolph, Ian Buchanan, Jennifer Hornery, Bill Jackson, John Jones, Torbjorn Kihlstedt, Gary Neilson and Harry Quarls – Booz•Allen & Hamilton

Executive Summary

From airlines to automobiles to advertising, the urge to merge has escalated steadily over the past decade. In 2000 alone there were 9,472 merger and acquisition transactions in the United States — a new record. Although this rush to the altar may have been grounded in solid synergistic potential, all too many of these marriages quickly faltered. Booz•Allen & Hamilton recently conducted a study of deals that closed in 1997 and 1998 and discovered that 53 percent of the deals had failed to deliver their expected results.

Although senior executives devote exhaustive hours to striking the right deal, it is merely the beginning of the long and tortuous merger integration process. In fact, structuring a deal is relatively easy; implementing one is nothing short of heroic. As an executive presiding over a newly merged company, you are inundated with competing priorities and demands. But the most important questions before you are these:

• How do you deliver on the value you promised shareholders and investors while simultaneously “keeping the wheels on the business”?

• In the wake of a merger, how do you successfully integrate operations while maintaining your focus on customers?

Although no one-size-fits-all formula can apply to every company’s unique situation, in our experience four principles are the key to success in merger integration. They all start with the CEO — before the deal closes.

• Communicate a shared vision for value creation.

• Seize defining moments to make explicit choices and trade-offs.

• Simultaneously execute against competing critical imperatives.

• Employ a rigorous integration planning process.

These four key principles will dictate a series of transformational priorities that will, in turn, shape the ongoing game plan and the categorization of day one versus longer-term tasks. This is an iterative process. If senior management sticks to it with rigor and clearly communicates evolving expectations, there is a strong likelihood that they can realize the promise they identified on the day of the merger announcement and keep all their constituencies — customers, shareholders, employees, and others — more than satisfied. This Viewpoint outlines Booz•Allen’s approach to achieving success in merger integration.

Most mergers fail. Though this reality is uncomfortable, it is an indisputable fact. By whatever measure you choose — stock price, revenues, earnings, return on equity — most deals fall short of expectations. Somewhere between the concept of the merger and its execution, the promise fades. Synergies evaporate. Savings vanish. Cultures clash. And the CEO discovers the door.

But why? Surely, no one enters into a merger intending to lose shareholder value. In a few cases, the merger itself was simply ill conceived: the promise was never really there to realize. In most deals, however, it is ambiguous leadership and poor execution that prevent companies from capturing the full value of a merger. Although senior executives devote exhaustive hours to striking the right deal, it is merely the beginning of the long and tortuous merger integration process. In fact, structuring a deal is relatively easy; implementing one is nothing short of heroic.

Although no one-size-fits-all formula can apply to every company’s unique situation, in our experience four principles are the key to success in merger integration. They all start with the CEO — before the deal closes.

1. Communicate a sharedvision for value creation.

2. Seize definingmoments to make explicit choices and trade-offs.

3. Simultaneously execute against competing critical imperatives.

4. Employ a rigorous integration planning process.

This Viewpoint outlines Booz•Allen’s approach to achieving success in merger integration.

A Marriage Made in Purgatory

From airlines to automobiles to advertising, the urge to merge has escalated steadily over the past decade. In 2000 alone there were 9,472 merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions in the United States — a new record. Worldwide, mergers and acquisitions through July 20, 2000 were valued at $1.7 trillion, an 18 percent year-over-year increase.

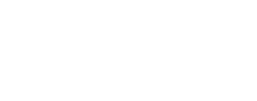

Although this rush to the altar may have been grounded in solid synergistic potential, all too many of these marriages quickly faltered. Booz•Allen & Hamilton recently conducted a study of deals that closed in 1997 and 1998 and discovered that 53 percent of the deals had failed to deliver their expected results. (To assess their post-merger performance fairly and accurately, we intentionally restricted our sample to those deals that had closed two or more years ago.)

“One of the best decisions we made in the merger integration process was to maintain our focus on customer service, even when it meant slowing down the rush to exploit synergies. If we kept our customers satisfied through the integration process, we reasoned, it was worth delaying the savings for a couple months.” — CEO, medical products and services company

Further analysis revealed that the more strategic the rationale for the merger, the greater the likelihood of failure (see Exhibit 1). Of those combinations that were simply intended to establish or exploit scale effects, 55 percent achieved their objectives. However, of those mergers with more strategic motivations (e.g., move upstream or downstream in the value chain, add capabilities, develop a new business model), only 32 percent realized their vision and objectives.

The widely prevalent “merger of equals” was also shown to be more failure prone. According to our analysis,mergers failed almost twice as often when the participants were of comparable size. Although most of the lessons in this Viewpoint are applicable to all deals, we will focus primarily on the issues attending large-scale mergers of comparably sized companies.

Integrating companies is a mammoth undertaking. The tactical issues aretremendous. Indeed, when companies explained why they had not met expectations, more than two thirds cited execution-related reasons — such as loss of key staff, poor due diligence, and delays in communication. Only 32 percent attributed their failure to meet expectations to more strategic concerns such as poor fit or an overly ambitious vision.

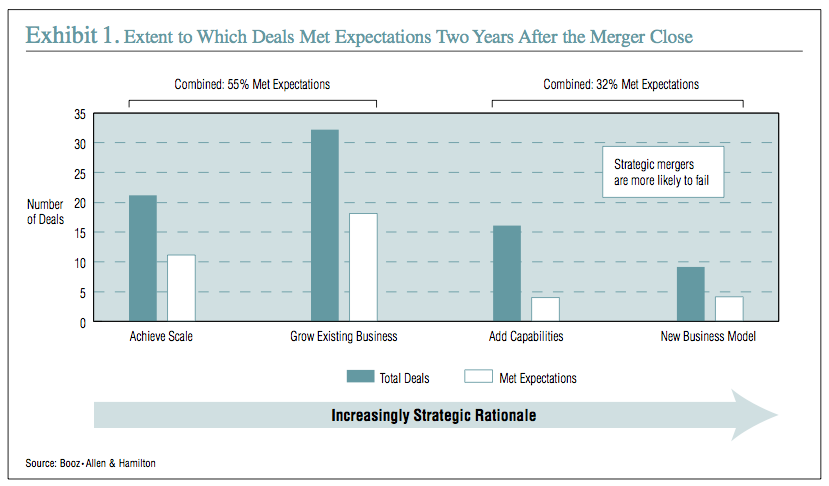

However, whether tactical or strategic, problems in merger performance land on the same doorstep: they are attributed to poor leadership. That is why so many CEOs lose their jobs within two years of the close of an unsuccessful large-scale merger. According to our research, among companies that did not achieve their targets, 42 percent saw the CEO depart within two years. That compares with a 16 percent departure rate among the CEOs of successful mergers (see Exhibit 2).

As an executive presiding over a newly merged company, you are inundated with competing priorities and demands. But the most important questions before you are these:

• How do you deliver on the value you promised shareholders and investors while simultaneously “keeping the wheels on the business”?

• In the wake of a merger, how do you successfully integrate operations while maintaining your focus on customers?

It’s important to start the merger integration process as soon as possible. To be successful, you must sow the seeds of integration well before the deal closes. That means making the following decisions early:

• How will we create value?

• How will we approach and structure the merger?

• How will we lead andmanage the integration?

• What is our peoplestrategy for the transition to the merged organization?

The unique characteristics of the deal will dictate the particular choices you make in each area; there is no one-size-fits-all recipe for successful merger integration. Comprehensive due diligence will inform these early decisions, which will then become the foundation of a rigorous integration planning process. The result: both organizations will be ready to integrate immediately after the merger’s close.

The Four Principles of Success

Our experience helping hundreds of companies throughout the world go through the merger integration process has distilled four key principles of success, all of which start with the CEO (see Exhibit 3).

PRINCIPLE 1: COMMUNICATE A SHARED VISION FOR VALUE CREATION

We have no doubt that every company goes into a merger with a one- or two-sentence description of what the deal is all about. And we have no doubt that a lot of time and effort goes into crafting that statement. However, we suggest that the senior leadership team dig even deeper, beyond the immediate rationale to the real and sustainable sources of value they hope to unleash in the merger, and then be aggressive and open in quantifying and communicating those sources of value to vested parties — employees, customers, and shareholders.

A true shared vision for value creation:

• Specifically identifies sources of value

• Sets high aspirations for financial growth and synergy

• Is shared by both companies’ senior teams

• Is communicated broadly and constantly

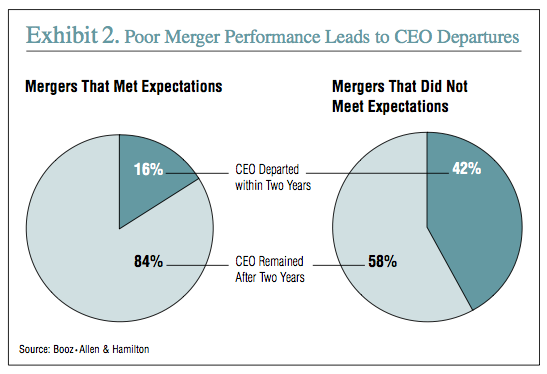

This vision is actionable. It spells out the strategic rationale for the merger and the goals for what the merged company can become. It gives the new leadership team marching orders and allows the organization as a whole to understand the immediate priorities in integrating systems, people, and processes. It sets stretch targets for financial growth and synergy capture (see Exhibit 4) so that the promise of the merger can be fully realized.

“A merger is like a marriage — it’s all about people and their ability to work together in a way that benefits the union. The basis for success includes a common understanding and assessment of what both sides bring to the party, and what the promise of the union is to be.” — CEO, global software developer

Moreover, the vision is truly shared — a notion frequently embraced in public statements but all too often disregarded in practice. Both companies’ senior teams need to understand and support the vision of what the merged company is trying to accomplish in order to realize those goals.

It is imperative that the companies be forthright and consistent in their communication of this shared vision for value creation and then “walk the talk.” The most successful merger integration efforts leverage multiple communication channels and do not underestimate the power of the daily dialogue between supervisor and employee. Constant and updated communications serve as a reality check for employees as they make daily decisions.

Finally, the organization needs to be equipped with the means to translate the words of the vision into deeds to effect a transition and successfully integrate people and assets. For example, we had a client whose vision was to use mergers and acquisitions to become the producer of choice in the premium beverage segment. The company translated that vision into action by developing a three-pronged plan: 1) build a full product portfolio for its distributors, reducing the distributors’ dependence on other suppliers; 2) establish the scale necessary to capture benefit along the full value chain; and 3) wield sufficient clout to alter industry relationships with distributors and retailers.

That clearly articulated rationale had direct implications for the client’s merger planning and execution processes. It called for a rationalization of the supplier base, the development of new relationship management capabilities, and the formation of processes to capture the “best of the best.” It helped senior management in designing the “new” organization, establishing HR policies, and outlining the operations footprint. It was a clear, actionable vision.

PRINCIPLE 2: SEIZE DEFINING MOMENTS TO MAKE EXPLICIT CHOICES AND TRADE-OFFS

Successful merger integration hinges on the senior leadership team’s recognizing key moments of truth in the merger process and acting decisively. They must consciously identify and evaluate all options and make explicit choices and trade-offs, recognizing that some choices will be very clear (given the vision and the characteristics of the deal), while others will require great conviction and fortitude.

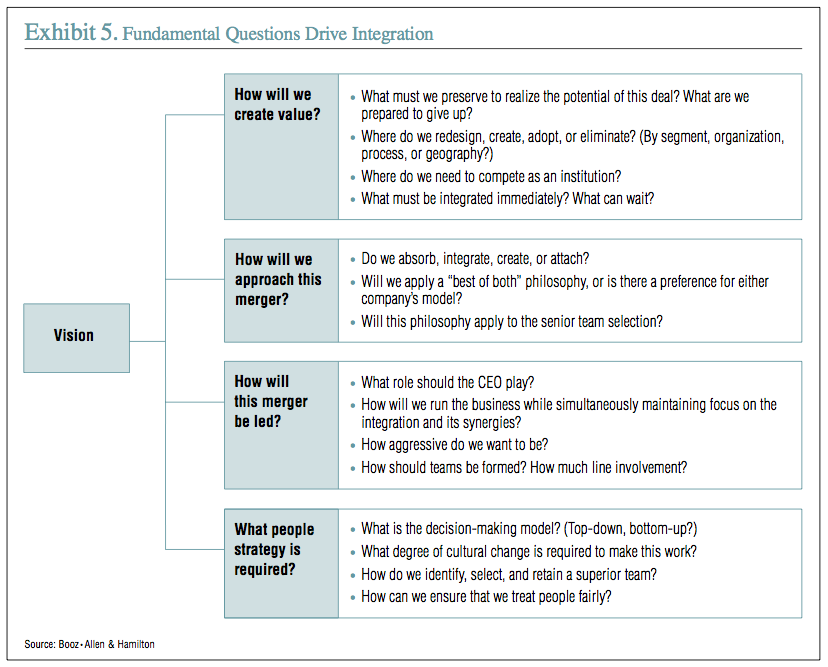

As we indicated in the introduction, four fundamental questions should drive the character and pace of any integration effort (see Exhibit 5).

First, you need to ask the fundamental question “How will we create value?” There will almost certainly be profound trade-offs when you address this question. What will you need to preserve to realize the potential of the deal? And what are you prepared to relinquish in return? Where should you redesign, create, adopt, or eliminate — and should you make these decisions by segment, organization, process, or geography? What are the immediate priorities and what can wait?

The second fundamental question concerns how you approach and structure the merger. Will you absorb, integrate, create, or attach? Will you take a “best of both” approach when it comes to adopting the companies’ practices, or will one company clearly dominate the other? Finally, will this philosophy apply to your selection of the senior team? The nature and strategic intent of the deal will lead to some specific choices. For example, if the deal is a “bolt-on,” in which one company is simply acquiring another’s revenues at a marginal fixed cost, then the integration approach is largely decided: absorb.But most deals of any size — our focus in this Viewpoint — involve a more complex set of competing issues.

Third, you need to ask yourself how the integration should be led. Should the CEO play a prominent role? How will you keep current businesses running smoothly while integrating new assets and realizing synergies? How aggressive do you want to be in exploiting new value? Once again, the nature of the deal and its impact on industry structure will lead to certain choices. As one CEO overseeing a mega-merger in his industry observed, “You have to be willing to bet the firm, and drive every aspect of the integration personally.”

Finally, what people strategy will be required? Will you use a top-down or bottom-up decision-making model? How will you integrate different cultures? How will you retain top performers while treating everyone with fairness and respect?

Some of these choices will be obvious given the nature of the deal. For example, in our experience clients who paid large premiums approach merger integration very aggressively. To recover their investment, they target early wins and exploit synergies immediately. A hostile takeover situation requires an early emphasis on people strategy. Such companies need to retain key talent and ensure knowledge capture. A high-profile deal with some market skepticism will require the CEO to play a visible role in the integration effort. And, depending on the sources of value you have identified, these will necessarily be given the highest priority as you focus resources on creating value post-merger.

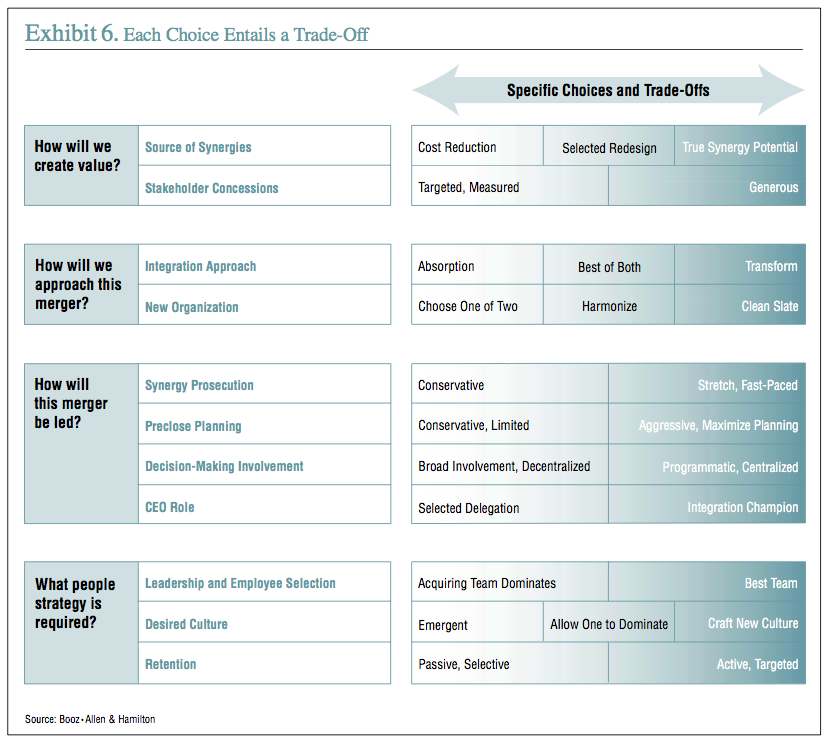

As Exhibit 6 highlights, each choice involves a trade-off.

Whether it concerns the integration approach, the desired culture, or the role of the CEO, each choice is made from a range of options. In exploiting synergies, you can focus simply on reducing existing costs or you can strive to create new primary demand. In developing the new organization, you can choose one model and jettison the other — or clean the slate entirely. In retaining people you can adopt

a passive approach or take a more active stand with targeted individuals. It’s a whole new ball game, and you get to establish the rules… all at once… in real time.

It’s in these CEO-level decisions that the future success of the merger lies. If you can pick your spot in each of these areas and establish a stake before the merger even closes, you’ve gone a long way toward ensuring the effectiveness of your post-merger integration efforts.

PRINCIPLE 3: SIMULTANEOUSLY EXECUTE AGAINST COMPETING CRITICAL IMPERATIVES

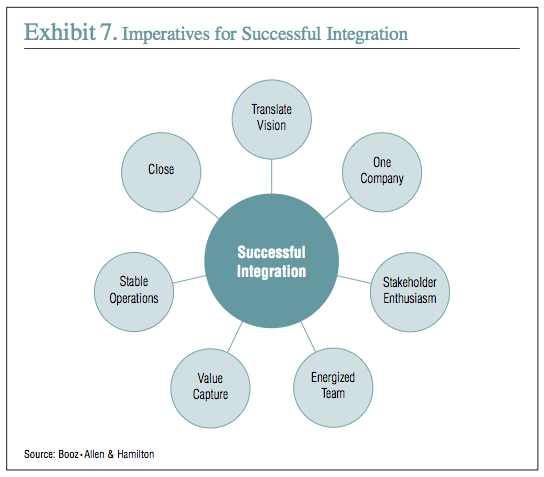

Companies need to balance several critical imperatives simultaneously as they map out and engage in the merger integration process (see Exhibit 7).

Translate the Shared Vision

As we mentioned before, the CEO’s vision must be actionable. The organization must be equipped with the means to translate mere words into deeds to effect a transition and successfully integrate people and assets. The balancing act here is to provide a road map clear enough to allow those implementing the vision to know specifically what they need to do — while not smothering the energy and creativity that it takes to realize the prize (that is, deliver on the commitments made at the time of the announcement).

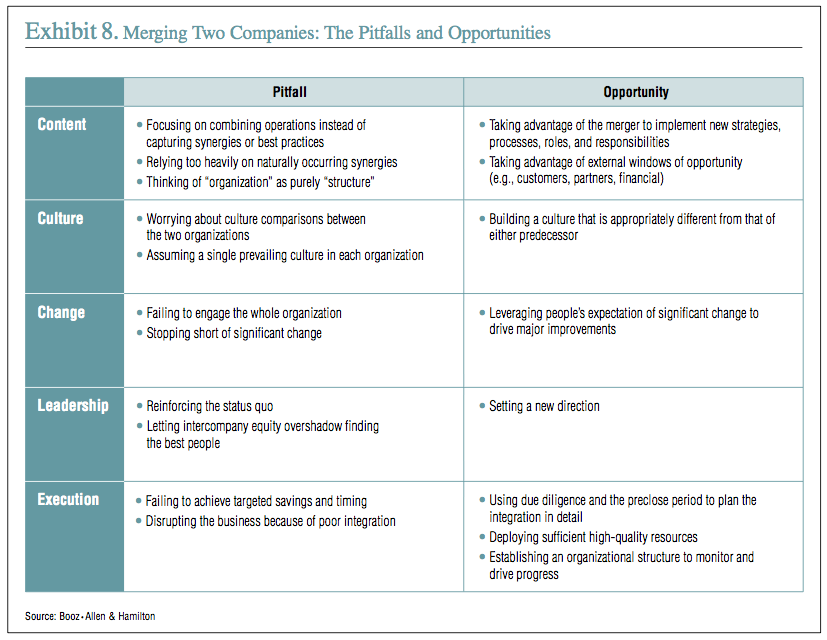

Create One Company

The challenge of creating one company from two formerly independent — and quite often competitive — organizations looms large. Those leading the new organization must quickly move beyond rhetoric to truly combine the two companies and create a single, bigger, and better competitor. The pitfalls are numerous (see Exhibit 8), but the opportunities to create new value are even more prolific.

Build Stakeholder Enthusiasm

In the wake of a merger announcement, CEOs and their senior managers must direct their focus not only within but also outside the organization and rally the enthusiasm of the various stakeholders that the new company will need to succeed. Good intentions do not always translate into good communication, which is unfortunate, since it is critical that key stakeholders — be they shareholders, customers, employees, suppliers, or regulators — fully buy in to the potential of a merger.

Everything communicates, not just press releases and official bulletins. You send a clear message to customers, for example, when you increase prices in the wake of a merger or cause customers to suffer service disruptions. What to say, to whom, when, and by whom are all critical ongoing decisions that need to be made quickly and clearly as part of an overall communications strategy that balances conflicting interests and messages.

It is tempting to tell everyone what they want to hear, but rarely, if ever, is that a feasible or realistic goal. The merger will, necessarily, create winners and losers among your various constituencies. In communicating with each of them, you should emphasize as honestly as possible what’s in it for them — along with the value proposition the newly combined company offers. For those who stand to benefit, regularly demonstrate progress; for those who will be negatively affected by the merger, mitigate fears. Focus first on those stakeholders, particularly customers, who are most at risk.

One Australia-based building products company we spoke with started managing its stakeholders even before it identified a merger partner. The CEO pursued discussions with industry peers while simultaneously preparing the ground with his board and shareholders by educating them on the underlying forces affecting the company and its growth options. This CEO saw this exercise as “earning the right to do a deal.”

Booz•Allen Client Case Study: Building Stakeholder Enthusiasm Client Situation

On the heels of a competitor’s failed acquisition attempt, our client entered tense negotiations with the target, a consumer and health products company.

Actions Taken

A forceful and comprehensive public relations campaign was waged to convince stakeholders of the merits of the deal:

- An aggressive communications program was aimed at institutional investors and the board of the target company, stressing the merits of the deal compared with those offered by the alternative suitor.

- A clear, simple message surrounded all merger communications.

- The company put an emphasis on the speed of closing.

Results

The company received positive press coverage of the deal merits and closed the acquisition expeditiously.

Unleash an Energized Team

Possibly the greatest challenge in merger integration is building an energized and enthusiastic team comprising the best of both organizations. It is the nature of any acquired company to resist directives, and employees at both companies will be consumed with questions about their individual futures in the wake of a merger announcement. Asking them to enlist in your shared vision without first allaying their concerns about where they fit into the new organization is an exercise in futility. Buy-in is a cascading process, so the obvious starting point is the leadership team. The CEO’s selection of his or her senior officers will set the tone for the new organization’s people strategy. Of course, whether people stay is the result of countless decisions made at every level. How positions are filled is as important as who fills them. How positions are “unfilled” is arguably even more important. We’ve seen client situations in which the casual assigning of office space brings entire departments to a halt.

True buy-in comes when employees understand clearly what is being asked of them and what opportunities for personal growth await them if they say yes. What are the career prospects? What are the financial upsides? In short, “What’s in it for me?”

Capture the Value Through Synergies

There will be significant pressure on the CEO and senior management to “realize the prize” in the first year or two. After the deal is paid for, these executives then need to justify it by delivering continuing upside. This is particularly difficult to do while you are trying to avoid a tide of employee departures and make sure your customer orders are filled. The trick is to identify the appropriate combination of short- and long-term synergies that will give external stakeholders faith in your promise of the prize, but that will not sap the organization of energy, thereby sabotaging the promise.

From our research and experience, most stakeholders grant you about six to 12 months to deliver short-term synergies.

Beyond that time, they expect you to start delivering the upsides.

So where do you start looking for this balance of synergies? First, it is critical to develop a solid fact base from which to build. This baseline provides a starting point and will allow teams to map the organizations against one another. Teams should then be given the task of looking for creative ways to improve the way business is done, getting beyond redundancy-based synergies.

Maintain Stable Operations

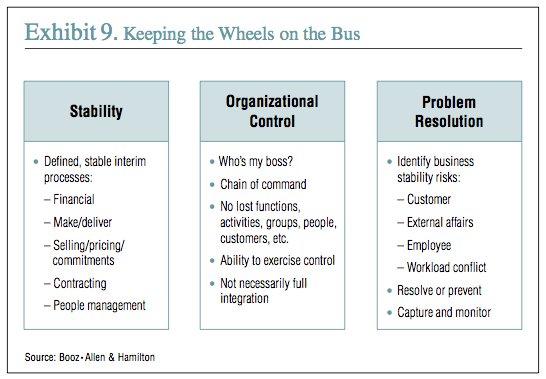

In the midst of mounting external pressures and multiple distractions and conflicts, it is easy for senior executives to lose sight of their primary responsibility: to keep the wheels on the bus. That goal is achieved by focusing on three primary areas: stability, organizational control, and problem resolution (see Exhibit 9).

Both in mergers of equals and in more straightforward acquisitions, a host of issues threaten to bring ongoing operations to a standstill. The key is to establish stable interim processes and controls as well as problem resolution mechanisms, so that there are no debilitating interruptions in service or defections in staff. Where are the risks to continued business stability? What can you do on a contingency basis to address these risks and prevent further escalation? Although integration decisions about the future-state organization and processes may take some time, it is imperative that you immediately resolve outstanding issues such as delegations of authority, payroll, workload conflicts, and pricing — even if that involves a temporary solution.

One individual we interviewed, the CEO of an Australian conglomerate with extensive merger and acquisition experience, recommends appointing risk management czars to identify and address threats to continued business stability. These individuals should be independent of the business units and should report directly to the CEO.

Booz•Allen Client Case Study: Maintaining Stable Operations

Client Situation

Our client in the aerospace and defense industry acquired a company in a similar line of business for a low premium. It was important to ensure minimal disruption to business operations given strict quality and timing requirements on existing key customer contracts.

Actions Taken

It was determined that many sites would ultimately be closed, but the low acquisition premium meant that the client had time to pursue this consolidation strategy more gradually. The client decided to implement consolidation moves over a period of several years after the deal closed.

The CEO also chose to keep the name of the acquired company, and he personally visited manufacturing sites to address management in an effort to ease the turmoil of the acquisition and ensure that people felt included and consulted.

Results

These decisions made for a smooth and successful integration.

Close the Deal

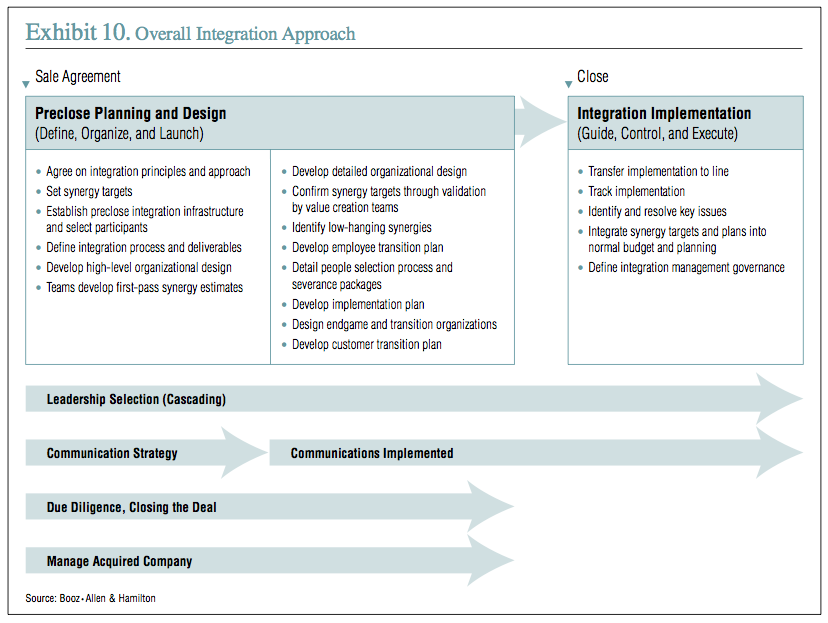

It’s telling that the final imperative is to close the deal; it only serves to emphasize the importance of beginning the post-merger integration process well before the deal is done. As the CEO of the newly combined entity, you will need to make key decisions and address critical imperatives in the period between signing the agreement and consummating the deal (see Exhibit 10). And, in doing so, you will need to balance the interests of all key constituents: shareholders, customers, employees, and regulators, among others.

Although the initial memorandum of understanding will set the broad parameters of the merger, there is often much room for last-minute maneuvering.

Different companies approach these negotiations in various ways, depending on the unique set of regulatory, competitive, and merger-specific issues that pertain to their particular situation. The key levers at your disposal in negotiating final deal terms will include the deal structure, regulatory commitments (e.g., pricing, employment, location of operations), savings targets, timing, and the distribution of risk.

The trick to closing the deal is to achieve a delicate balance between aggressively pursuing the deal consummation and crossing the line on legalities (or rupturing the deal altogether).

PRINCIPLE 4: EMPLOY A RIGOROUS INTEGRATION PLANNING PROCESS

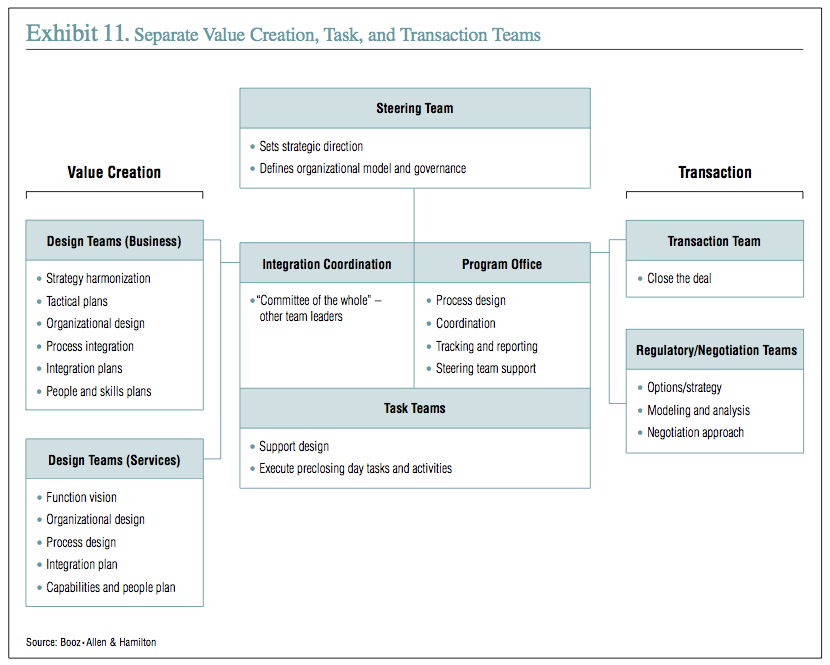

By the time it reaches full swing, the work of post-merger integration is a massive, multifaceted campaign involving every function and business unit along with personnel at multiple levels. But the planning process for this assault starts small and early with a design team staffed by a few select participants. As the merger passes through successive milestones — legal, regulatory, financial — the planning effort gains specificity as more information is shared. What started with one design team proceeds with multiple teams working in parallel. These teams spawn subteams that work on specific initiatives until hundreds of people are involved in the merger integration process. As teams evolve over time, they tackle the work implied by the key principles in greater and greater detail.

The first challenges in the planning process are to determine the right team structure and roles, select the right people for these roles, and decide to what degree you will involve line management. Most integration efforts require some combination of design or value creation teams, task teams, transaction teams — and a dedicated team to ensure that the businesses keep running. Value creation teams are focused on the future organization and the way business will be carried out as well as how to transition from the current state. Task teams, in contrast, are almost solely focused on day one critical activities to support bringing the two organizations together as one. The transaction team understandably focuses on closing the deal and is generally staffed with a cross-section of functional experts from legal, finance, and the different businesses.

In selecting the right people for the roles on these teams, it pays to think about the different skills required for each team. A conscious decision should be made about the ability of one person to fulfill both a value creation team and task team role. This is particularly important for the support functions of human resources, finance, and information technology. The integration support demand on these functions is enormous, yet they also need to be thinking about building an integrated function to support the future organization.

The work of these transaction, task, and value creation teams is then fed into a central program or integration coordination office overseen by a steering committee of high-level executives charged with charting the strategic course of the new enterprise (see Exhibit 11). All teams should be staffed with full-time stars rather than part-time understudies, and these individuals should be given tasks with specific and tangible objectives.

The CEO and top leadership should set aggressive but viable targets with clearly defined deliverables. In the interests of speed and credibility with the Street, the aggressive realization of synergy targets should be amply rewarded, and senior management should encourage as much sharing and collaboration as is legally permissible.

But leaders should take care to temper this zeal with restraint; otherwise, they risk burning out their best employees. We’ve seen clients charge their high performers with significant integration duties pre- and post-merger, without relieving them of their normal line responsibilities, resulting in physical and mental exhaustion and compromised performance.

Booz•Allen Client Case Study: Keeping Transaction and Value Creation Teams Separate

Client Situation

Two leaders in the medical products and services industry announced their decision to merge. The companies had very different operating models and had been pursuing distinctly different strategies.

Actions Taken

The use of integration teams allowed the company to dedicate resources to the merger while keeping the businesses running.

• Line managers maintained their focus on day-to-day operations.

• Full- and part-time integration teams performed the pre- and post-merger work. Integration teams were set up outside the normal organizational structure to remove them from undue influence.

Results

Integration teams were able to produce better solutions to the post-merger problems than line management could have, because:

• The multi disciplinary approach ensured that all functional voices were heard.

• Teams were often given freedom to review even the sacred cows of the organizations.

• The integration teams had an objective way of determining the best solution for the merger of such different organizations.

Pulling It All Together

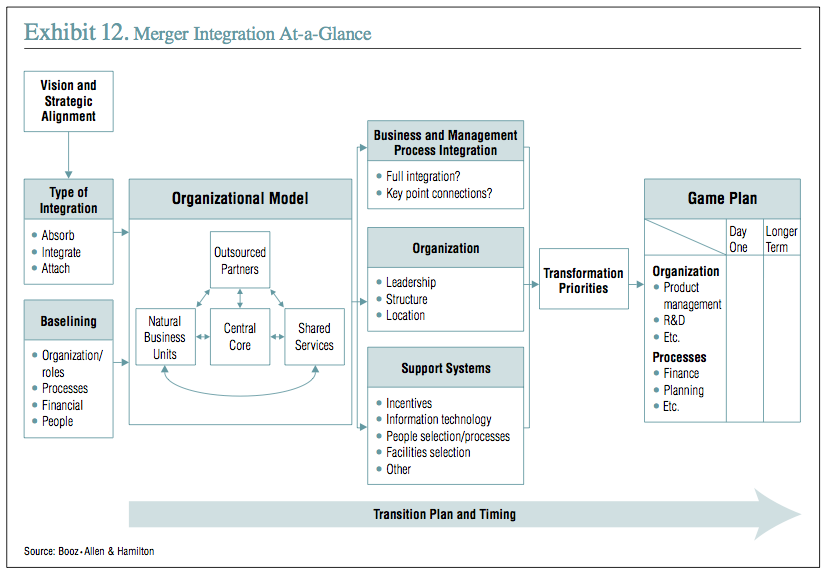

In our experience, the most successful merger integrations begin with a clear and broadly communicated game plan that addresses each of the four principles we’ve just outlined (see Exhibit 12).This game plan is inspired by the shared vision articulated at the time of the merger announcement and the type of integration anticipated, whether it is absorption or a union of equals.

Based on this vision and approach, the game plan will need to address the inevitable organizational issues that will surface. How will the two companies work together? Will new business units be formed? Where will the central core or headquarters operation be located and how will it be staffed? What services will be outsourced and/or rationalized? These are among the explicit choices and trade-offs that need to be resolved at the outset of the merger integration process.

This ongoing organizational model will influence to a great degree how the actual integration implementation unfolds. Guided by the principles we’ve just discussed, companies will make further rounds of choices about business and management processes, organizational structure, and support systems.

These four key principles will dictate a series of transformational priorities that will, in turn, shape the ongoing game plan and the categorization of day one versus longer-term tasks. This is an iterative process. If senior management sticks to it with rigor and clearly communicates evolving expectations, there is a strong likelihood that they can realize the promise they identified on the day of the merger announcement and keep all their constituencies — customers, shareholders, employees, and others — more than satisfied.

e-Merger: Expediting PMI Information Flows

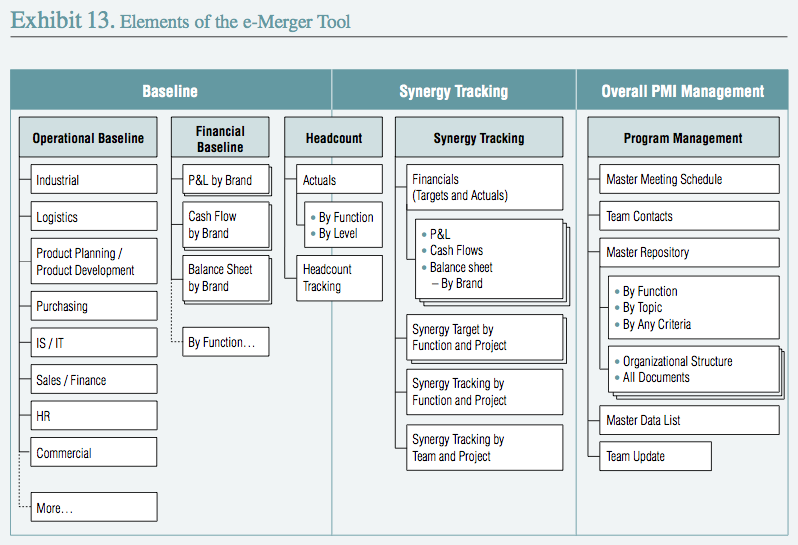

The Internet has an obvious role in post-merger integration (PMI), as it does with most information-intensive processes. At AESTIX, a Booz•Allen & Hamilton subsidiary, we’ve developed a Web-based tool called e-Merger to facilitate preclose planning and post-merger integration work (see Exhibit 13). The e-Merger tool provides baseline, synergy tracking, and program management functionality and dramatically collapses the time frame for a given merger. It also provides a common, secure, and ubiquitous platform for the assembly and dissemination of “clean room” documents. Access is customized to an authorized user’s needs.

e-Merger jump-starts the integration planning process, especially for large multinational companies contending with highly fragmented information, differing accounting standards, and other inconsistencies across geographies. It helps senior executives and managers make better, faster, and more informed strategic and operational decisions.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter