Publications M&A Beyond Borders: Opportunities And Risks

- Publications

M&A Beyond Borders: Opportunities And Risks

- Bea

SHARE:

By Marsh, Mercer, Kroll (EIU, MMC)

About the survey

The Economist Intelligence Unit surveyed 670 executives in January 2008 about their attitudes to cross-border mergers and acquisitions. The survey and paper were sponsored by Marsh, Mercer and Kroll. Respondents represent a range of different regions, with approximately 30% from Asia-Pacific; one-quarter each from Europe and North America; and the remainder from the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Executives questioned represent a range of company sizes, with approximately 50% reporting annual revenues of more than US$500m and the remainder under that threshold. Approximately 50% of respondents were C-level or board-level executives and the remainder were senior executives.

The Economist Intelligence Unit conducted the survey and wrote the paper. The findings expressed in this summary do not necessarily reflect the views of our sponsors. Our thanks go to the survey respondents for their time and insight.

Highlights

To complement the findings from the Economist Intelligence Unit’s survey, experienced M&A practitioners from Marsh, Mercer and Kroll have contributed their observations on the challenges and opportunities available to both strategic and financial deal makers. Their insights are organised in the following pages by geographic region.

Emerging market corporations are confident to do deals

Emerging market corporations are now more confident in their pursuit of M&A. Chinese, Indian and Russian companies have been prolific in venturing outside their domestic markets to do deals, demonstrating that they are well-managed, efficient and globally competitive. Many of them have recently had initial public offerings on stock exchanges – not so much to raise capital as to demonstrate greater transparency, dispel perceptions of reputational issues and effectively pave the way for future M&A deals.

Some geographic areas require careful analysis of political and security risks

Terrorism, political instability, corruption, kidnapping. All are issues that may need to be considered, as acquirers look to emerging markets for raw materials, low-cost manufacturing and new markets. The downside of these dangers is evident, yet uncertainty creates opportunities for those willing to take calculated risks in some areas of Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and parts of Asia and Eastern Europe. Partnering with trusted advisers on the ground can be the difference between success and failure.

Workforce issues vary substantially around the globe

How feasible is a post-deal workforce reduction? Are local employment regulations loose or tight? Can people be shifted to performance-based pay? Everyone knows about strict lay-off and employment rules in France, Germany and Italy, but acquirers seeking opportunities in parts of Latin America, Africa and the Middle East will find some of the same. Global deal makers need to understand the rules and industry practices.

Consideration of environmental issues must be reflected in the deal

Around the world, governments are making rapid and sometimes sweeping changes to environmental legislation. While the degree of environmental litigation and statutory enforcement in some countries still lags well behind North America and Europe, deal makers should be mindful of greater regulatory scrutiny of their operations, stricter enforcement of environmental legislation and the extent of environmental liabilities they may assume in a merger or acquisition.

Redefining due diligence as M&A goes global

Due diligence is, fundamentally, a risk management activity, yet in many markets risk and insurance reviews are excluded from a bidder’s due diligence. This can be a dangerous oversight, as deal makers may underestimate the liabilities and risks they inherit and overestimate the insurance assets of the target company. This is particularly true in cross-border acquisitions, where determining the true cost of risks requires a more forensic analysis and a solid grounding in the local risk management culture as opposed to a mere confirmatory review.

Insurance capital can be used to overcome deal-specific concerns

Investing in an unfamiliar country can make even the most straightforward venture seem risky, particularly when an acquirer is being asked to accept a level of warranty and indemnity (or representations and warranties) recourse from the seller that is significantly below the overall transaction price. Increasingly, deal makers are strengthening their negotiations by tapping into warranty and indemnity insurance to avert lengthy negotiations or even potentially deal-breaking situations.

People matter in every phase of the M&A process

Since almost 0% of corporate revenues are spent on people (salaries, benefits, hiring costs, etc.), deal makers must pay close attention to human capital issues in every phase of the M&A process – and the earlier the better. In Japan, for example, a deal that fails to demonstrate tangible benefits for target company employees, not just the acquirer’s shareholders, may not get off the ground. In China, wage inflation is becoming a serious problem for owners, and India is fast running short of technically trained people.

M&A goes global: the geography of deal flow

The world of M&A has gone global. Twenty years ago, much activity would have been focused on the domestic or local market, but companies today are increasingly seeking targets in more far-flung destinations. The rapid development of some countries in Asia, the Middle East and Latin America has created a whole host of new opportunities for acquirers in these regions, while at the same time turning local companies into acquirers in their own right. This world map charts the predicted direction/ level of outward and inward M&A deal flow, with figures for appetites based on our survey.

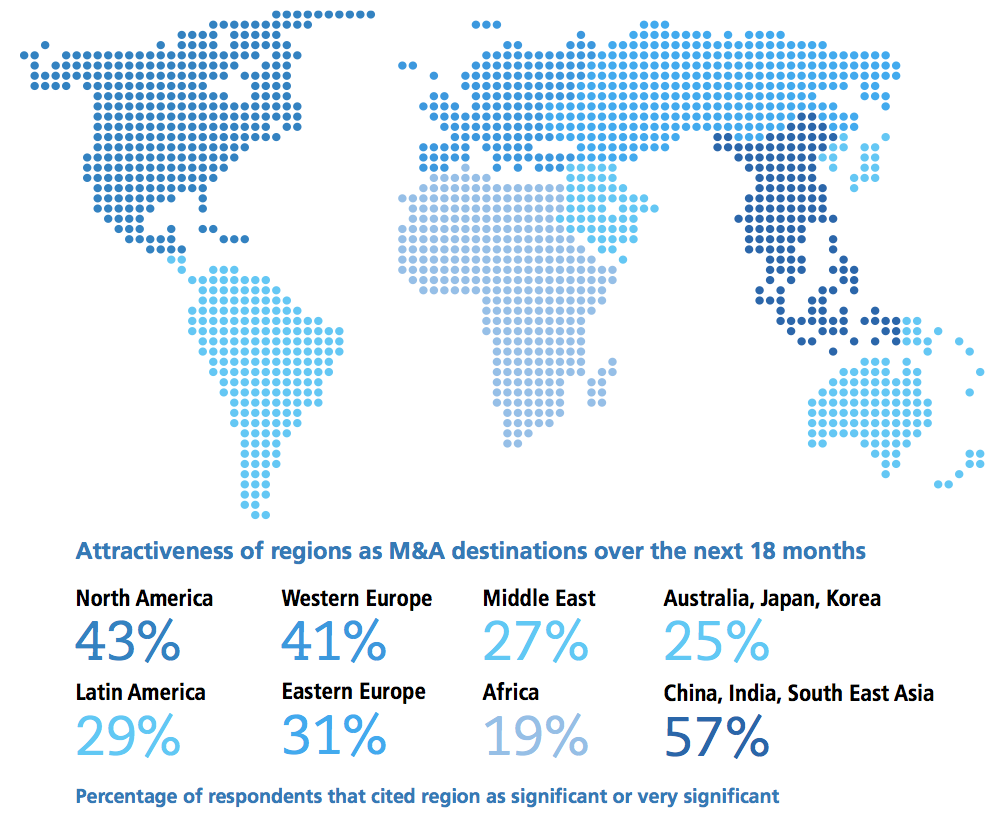

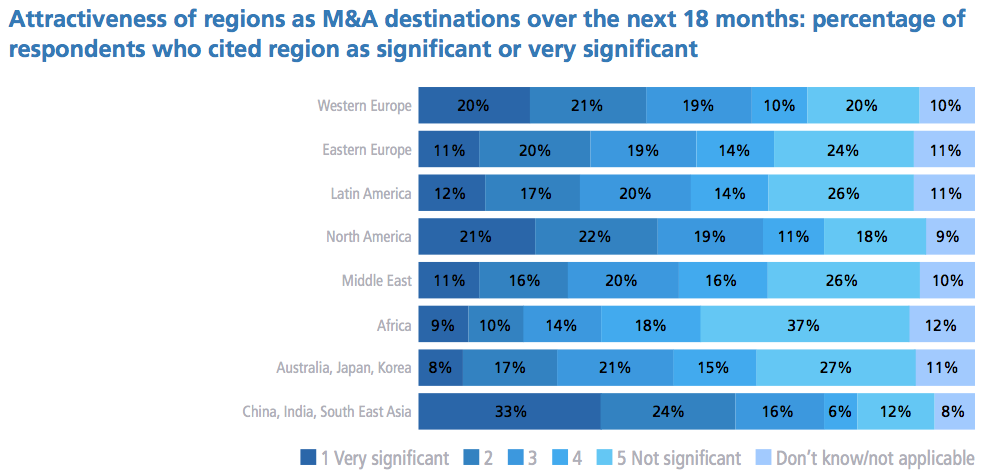

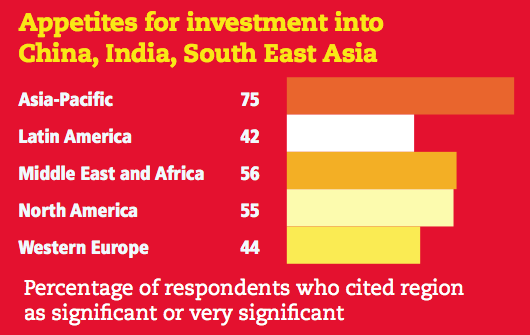

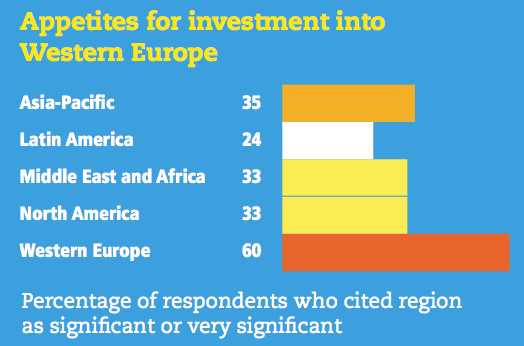

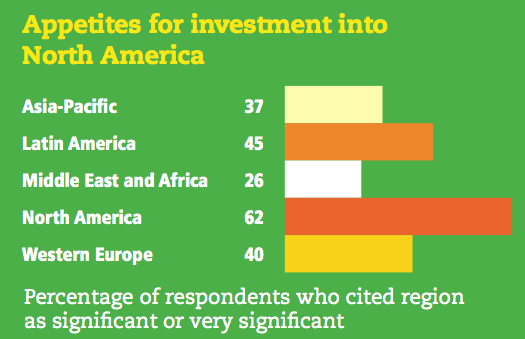

On the surface, the main message of the survey seems to be that M&A money is headed for the rapidly developing economies of China, India and South East Asia. Nearly six in ten respondents say that these countries would figure significantly or very significantly in their companies’ M&A strategies, well ahead of the figures for the next two regions, North America (43%) and Western Europe (41%).

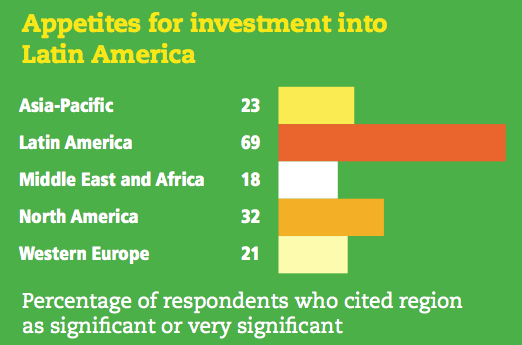

While in aggregate, developing Asia is the region that generates the most interest, a closer examination of the regional results reveals a more nuanced picture. For each regional set of respondents, the preference is to invest in the home region first. This is true for both developed and developing markets and is likely to reflect a desire to conduct transactions in a culture and business environment that is familiar. Domestic and cross-border transactions may have different objectives: the former may still be undertaken to achieve superior buying power or operational efficiency, while the latter is more likely to be sought in order to pursue geographical growth strategies.

The greater appetite of smaller firms for M&A over the next 18 months is likely to reinforce the preference for the local. In our survey, smaller companies in North America and Europe are strongly attached to their home markets, while larger ones are more likely to have an interest in China, India and South East Asia. With scale comes an ability to conduct more ambitious deals, along with the resources required to integrate successfully across borders.

Nevertheless, cross-border M&A deals in the mid-market are also becoming more commonplace. The most active sectors include energy, mining, financial services, and power and utilities. The trend for M&A deals among smaller and medium-sized companies is likely to intensify as a result of more attractive valuations in the wake of the credit crisis, with both trade and financial buyers certain to be on the hunt for potential targets.

The tremendous growth of the economies of India, China and South East Asia is clearly attracting investment. And yet the flow also represents a degree of anomalous risk-taking. In general, M&A flows reflect perceived risks, with more money going to perceived safer destinations. But India, China and South East Asia are exceptions to the rule. As noted below, they are perceived as being among the riskiest destinations according to a number of measures, and are surpassed only by Africa in this regard. The potential rewards will have to be great to match these risks, and companies pursuing M&A strategies in the region will need to play extremely close attention to a broad range of risks that may lie outside of their familiar experience.

A pursuit of growth: the rationale for M&A

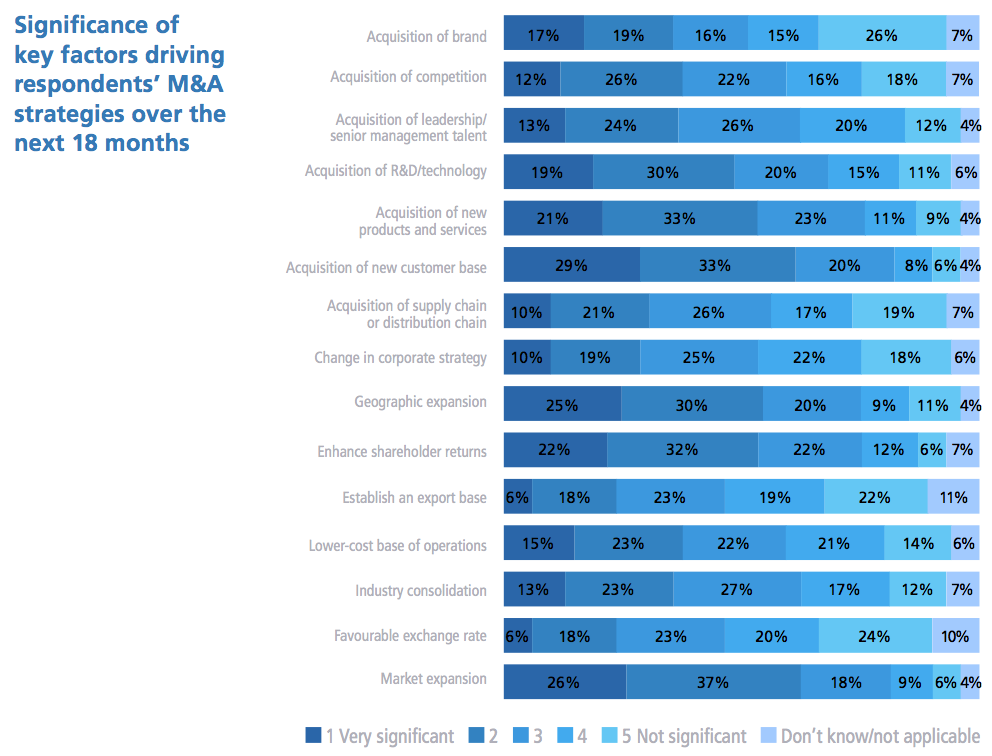

Companies currently see M&A as a tool for offence rather than defence. Whereas these transactions previously may have been undertaken to achieve economies of scale or erect a defence against predators, they are now seen as a valid strategy for pursuing market or geographic growth strategies. Indeed, market expansion was the leading motive for M&A activity, with 63% calling it a significant factor, followed closely by acquisition of a new customer base (which 62% saw as significant) and geographic expansion (which 55% felt was significant). The emphasis on growth was consistent across all regions and this broad desire to use M&A to secure larger markets suggests that companies around the world may be finding organic growth insufficient to continue to meet performance goals and the demands from shareholders.

Opportunity and risk in cross-border transactions

An appetite for M&A, despite clouds on the horizon

Recent evidence suggests that the credit crisis has already had a dramatic impact on the volumes and ambition of global mergers and acquisitions. Several large transactions have been put on hold, and data for the second half of 2007 revealed that deal volumes were substantially lower than for the first half.

Yet, set against this current environment, deals are still taking place and optimism around the growth potential of M&A remains strong. Despite a fall in volumes, 2007 was still a record year for M&A, with global transactions reaching US$4,740bn. And, as Microsoft’s US$44bn bid for Yahoo! suggests, it may be too soon to say that the mega-deals of the past few years are entirely a thing of the past.

In the mid-market in particular, deal flow is expected to remain strong. Many private equity firms are retreating into smaller deals, where high levels of debt may not be required, or are deploying funds to developing markets, where deals are more likely to be medium-sized. The pipeline for deals emanating from corporate buyers in the mid-market is also expected to remain strong. These transactions tend to be conducted for strategic reasons, and are less likely to rely on high levels of leverage than those undertaken by financial buyers.

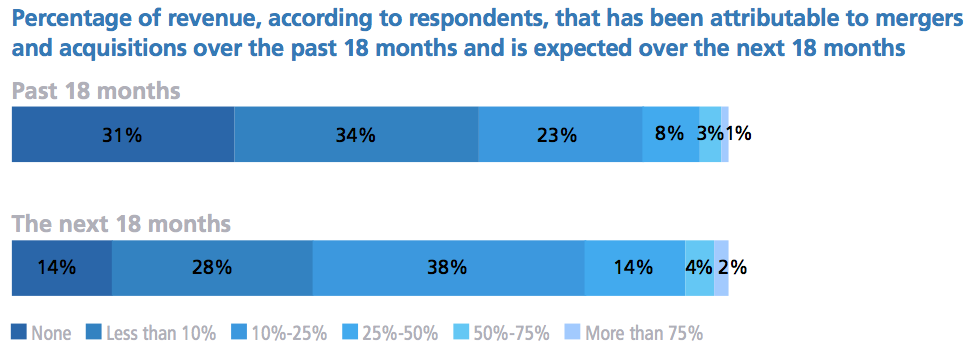

Among the 670 respondents questioned for the Economist Intelligence Unit’s survey, conducted on behalf of Marsh, Mercer and Kroll for this report, appetites for future growth from M&A appear strong. On average, respondents say that 12% of their revenue growth over the past 18 months has come from mergers and acquisitions – and that they expect this to increase to 18% over the next year and a half.

In the mid-market, deal flow is expected to remain strong

The numbers also suggest that recent history, as much as financial considerations, affects the extent to which companies will rely on M&A in future. For example, large European firms, on average, attribute more than one-fifth of their revenue growth over the past 18 months to M&A, but they expect this to drop to 14%. Such companies may simply be digesting their acquisitions, or recent experience may have tempered their views about the potential gains available.

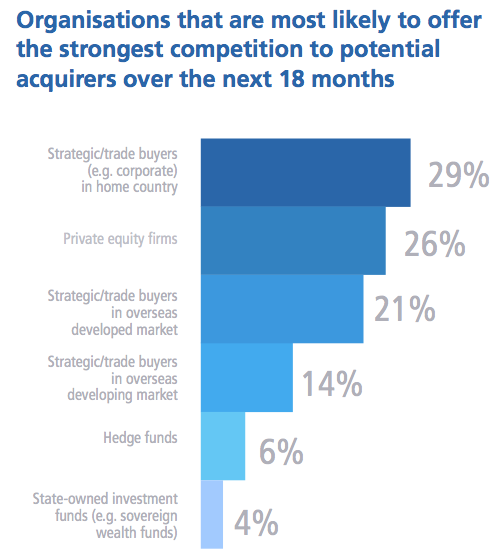

Strategic buyers

In pursuing M&A targets, corporates see their peers as the main adversaries. Nearly two-thirds point to strategic buyers of some description as the strongest competition on any potential acquisitions, versus 36% identifying financial buyers. The strength of strategic buyers in the current market is likely to reflect a number of trends: the strong balance sheets of potential acquirers; increasingly attractive valuations; and the scaling back of private equity ambitions. The strongest competitor for potential acquirers that was cited was strategic buyers in the respondent’s own home market. This reflects the tendency of companies to focus their attention on markets they know well. Yet an increasingly global market place has engendered global M&A flows. In total,35% of respondents consider strategic buyers from elsewhere in the world as their main M&A competitors–and of these more than four in ten worry about buyers coming from the developing rather than the developed world. Last year, India’s Tata Steel successfully bid for the Anglo-Dutch steelmaker Corus for£6.2bn. More recently, theUS$14bn pre-dawn raid by China’s Chinalco to interfere with BHP Billiton’s take over of Rio Tinto has been a particularly dramatic case in point.

Private equity may not have the headline-grabbing role in M&A markets that it did just a year ago, but it remains a substantial player. Although the volume of deals in the second half of 2007 dropped considerably compared with the first half, there is still plenty of private equity activity, especially among small and mid-sized companies. Leading private equity firms such as KKR and Blackstone are now competing with mid-sized funds in seeking out deals among smaller and medium-sized companies. And an article in the February 29 edition of the Financial Times suggested that firms such as Apollo, Blackstone and KKR were in the process of raising tens of billions of dollars for new funds, with growing allocations from sovereign wealth funds.

Appetites for future growth from M&A appear strong

- Companies in the Asia-Pacific region expect to rely most heavily on an M&A growth strategy, with the share of revenue growth for which M&A is responsible predicted to grow from 11% to 19%. North American respondents are looking for a similar increase, from 10% to 17%, while Europeans expect revenue growth from M&A to remain flat at an average of 13%.

- Smaller and medium-sized companies have higher expectations from M&A than larger ones do. Those with annual revenues under US$500m hope to see the contribution of M&A to growth double, from 9% to 18%, while the biggest firms–those with revenues exceeding $10bn – expect a slight decrease, from 14% to 13%.

- Expectations vary between sectors as well. At one extreme, information technology and media executives hope that M&A’s contribution to growth will double from 10% to 20%, while manufacturers foresee a small shift, from 13% to 16%.

Private equity remains a substantial player in M&A markets

Out of the financial buyers, private equity is by far the most frequently cited source of M&A competition and is second only to home market strategic buyers. Among Asia-Pacific respondents, private equity was seen as the strongest competition of all. Most commentators forecast continued growth for private equity in the region, especially if, as has been the case so far, Asian banks can avoid the huge write-downs associated with the credit crisis that have been seen in the US and Europe.

Private equity versus strategic buyers

Survey respondents rate strategic buyers as fiercer deal competitors than private equity firms. But don’t count private equity out! Private equity firms have been raising more and more investment capital. In 2007, US private equity firms alone raked in a record $302bn across 415 funds, and some industry watchers predict 2008 to be another record-setting year, driven by government investment funds and by perceived investment opportunities in emerging markets that have so far escaped the downturn threatening the US and Europe.

Despite the current credit malaise and rising borrowing rates, the McKinsey Global Institute projects that the industry’s total assets under management may double by 2012 to $1.4trn. That rising tide of private equity cash will have to find a home in the transaction marketplace, and corporates will find themselves competing with private equity for deals.

The leverage private equity firms secure may be at lower multiples in 2008 than during the first half of 2007; however, the price of many potential targets may drop due to economic conditions, leaving private equity to continue being a significant force in 2008’s deal landscape.

For their part, strategic buyers may pull back from the transaction marketplace in 2008 if the economic environment continues to sour, preferring to conserve cash and support their share prices through share buybacks.

So before you count private equity out, remember one thing: private equity firms exist to do deals, whatever the economic environment, whereas strategic buyers have broader agendas.

Broadening markets constitutes one approach to enhancing growth

Shareholder value

Another widely cited motive for M&A was enhancement of shareholder value, which was considered significant by 54% of companies. Although transactions of this nature are by no means guaranteed to achieve this goal, the majority of respondents to our survey claimed some success in this area. Among those who had completed such deals, 64% indicated that their last cross-border M&A transaction – often the most difficult kind – had enhanced shareholder value.

Broadening markets and increasing the customer base constitute one approach to enhancing growth; selling better widgets is another. Just over half of respondents said that the acquisition of new products and services was a significant factor driving M&A. Although 49% cited the acquisition of R&D as a significant factor, 61% of respondents from both IT and media – industries that are heavily reliant on intellectual property – saw it as significant. Figures were similarly high for the pharmaceuticals sector. In both cases, these factors were at or near the top of all reasons for M&A activity.

Global heat chart: Risk environment

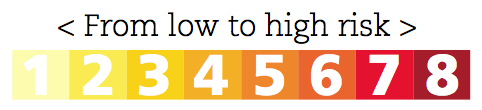

The global heat chart illustrates how survey respondents perceive a range of risk categories associated with investing in key regions of the world. Regions with the highest score are those where respondents perceive the greatest level of risk in the context of existing or potential cross-border transactions. The scale runs from 1 to 8, where 1 is lowest risk and 8 is highest risk.

The broad expectations about risk in these zones can help to explain the opportunities in cross-border M&A

Relative regional risk

Every cross-border transactions carries risk, but the severity and nature of those risks varies widely from region to region. In our survey, respondents were asked to consider risk issues associated with cross-border transactions in eight different regions: North America; Latin America; Western Europe; Middle East; China, India and South East Asia; Eastern Europe; and Japan, Australia and Korea. One caveat that should be mentioned is that this approach clearly requires respondents to comment on areas that are politically, economically and culturally heterogeneous. Nevertheless, the broad expectations about risk in these zones can help to explain the opportunities and challenges involved in cross-border M&A.

Risk and reward

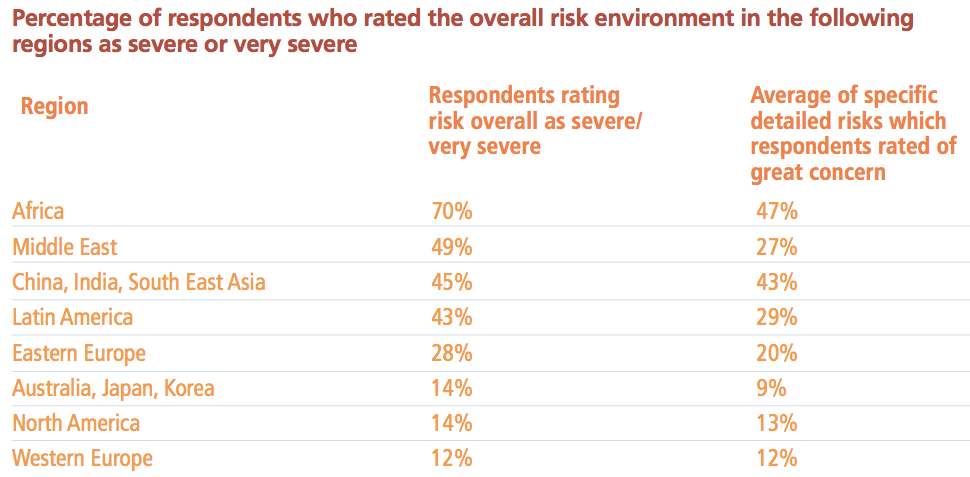

It comes as no surprise that, broadly speaking, respondents divide the world’s regions into two: less risky developed economies and riskier developing ones. The proportion of respondents rating the overall risk environment of a region as severe or very severe dramatically splits the wealthier geographies, including North America, Western Europe and select developed Asia-Pacific states (Japan, Australia and Korea) from the developing ones, with Eastern Europe caught in between. Moreover, this pattern of low risk in the developed world and high risk elsewhere repeats itself when respondents consider specific risks. The important exception to this rule is the threat of protectionist sentiment, where there is far less correlation with the wealth of the economy than with other risks. Although respondents see protectionism as a major concern in China, India and South East Asia, the developed markets of Western Europe, North America and the developed Asia-Pacific are very close behind. There is a similar trend with the litigation culture and environmental liabilities – both of which figure highly in developed countries, and especially in North America.

Africa

Our survey indicates that Africa is considered the riskiest region in the world, both overall and in terms of most of the specific issues. Deal volumes within the region, or into the region from elsewhere in the world, remain small, but are rising steadily. Evidence that there are growing expectations from African M&A can be seen in the recent acquisition by Standard Chartered of a stake in First Africa, a boutique M&A house based in Johannesburg and Nairobi.

South Africa in particular has seen record figures for M&A over the past five years. Around one-fifth of this activity in value, and one-third in deal numbers, arises from the government’s Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) initiative, which is designed to encourage black ownership of business. Although some foreign investors have been put off by the attendant regulations, a code of BEE good practice promulgated in 2007 should at least bring greater clarity.

Despite this trend, the region still faces many problems, according to our respondents. The most significant is perceived as being, simply, a lack of some of the basic necessities of modern business. The continent’s inadequate physical infrastructure, such as ports or railways, is a great worry and causes respondents to give this risk a very high score of eight – the highest in the entire survey. Even in South Africa, the continent’s most developed country, infrastructure issues can be highly problematic. In January, the country experienced a series of power cuts as Eskom, the state-owned power utility, cut supplies to homes and businesses across the country in response to an electricity shortage. These shortages are expected to last until 2013.

Key aspects of business infrastructure, such as risk management, corporate governance and reporting, are also perceived as being weak in Africa as a whole and each attracts a score of seven. A closely related problem is the difficulty in attracting the required management and worker talent – without the fundamental human resources in place, any significant improvement in business capabilities is likely to be slow to materialise.

Politics and economics are also deemed to pose high risks. The region scores highest out of all the regions studied for traditional political risk, currency volatility and market volatility. It also attracts the highest score for perceptions of bribery and corruption. According to Transparency International, 19 of the 40 countries considered the worst for corruption are on the continent and 45% of all residents seeking public services last year were asked for a bribe.

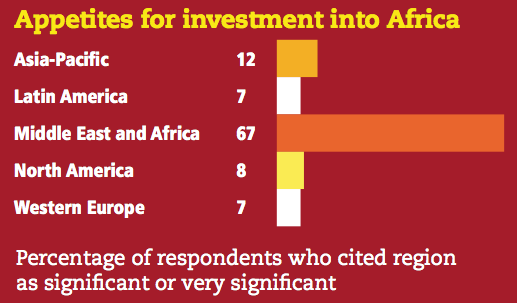

The one bright spot is that the region is seen as the least protectionist for any company wishing to invest there. This, coupled with the continent’s rich natural resources, has attracted a stream of investment in recent years. Although the region is seen by respondents as the least attractive investment destination, one in five still ranked it as significant to their near-term M&A strategy. To understand why, it is important not to let the overall picture obscure the bright spots. Africa has 54 countries, whose conditions range from the lawless anarchy of failed states to rapid development and relative wealth, such as that witnessed in Botswana and South Africa. Written by the Economist Intelligence Unit

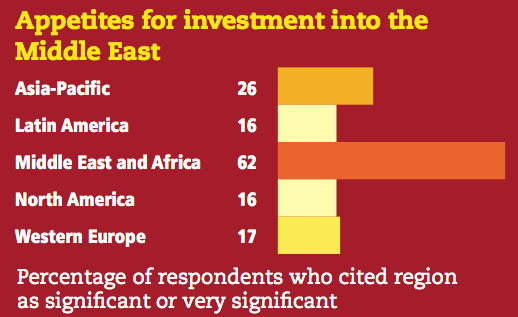

Appetites for investing in Africa are highest within the region itself and among Middle East investors. Elsewhere in the world, appetites seem somewhat muted, although there is some interest from investors in Asia-Pacific.

Scanning Africa’s horizon

Elections are planned in eight African states in 2008: Angola, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea, Mauritius, Rwanda, Swaziland, Zimbabwe and Cote d’Ivoire. This would seem to be good news – but alleged electoral fraud in Nigeria, post-election violence in Kenya, and conflicts in Chad, Sudan and the oil-rich Niger Delta have dimmed prospects for what many had hoped would be a more democratic continent. Nor have external efforts had much success. The summit of EU and African heads in December 2007 was supposed to herald a “new partnership”. Instead, deep divisions over free trade have cast a shadow over commercial relations which could produce tariff increases that would devastate some African economies.

Despite all the bad news, one can point to areas of economic vitality and a more hopeful future: Angola is anticipating 21% GDP growth in 2008 (albeit a GDP per capita of only $3,820) and Equatorial Guinea predicts 11% growth – a rate higher than China’s. Mozambique has shown outstanding economic growth since its civil war ended in 1992. Its GDP growth has averaged 8% per year over the past ten years. According to the UN Economic Commission for Africa, the region’s economies are expected to grow by an average of over 5% in 2008. That rate is higher than the EU’s and far outstrips that of the US. Overseas investors have noticed some silver in the dark clouds that hang over much of Africa. China, hungry for raw material resources, is making significant investments in Africa’s mineral wealth.

Political instability means that there are obvious downsides to longer-term business investments in Africa. However, uncertainty presents opportunities for those willing to take calculated risks. Both elements – risk and potential reward – must be understood in the present and the foreseeable future. To be successful, investors require excellent risk-assessment skills and risk management strategies.

Risk management in the context of Africa’s political instability involves both transferring the financial consequences to others, such as the insurance market, and applying risk mitigation measures, such as business continuity and security. Insurers view the political risks in terms of violence (civil strife, sabotage, terrorism and strikes) as well as host-government interference (expropriation and embargoes) and currency inconvertibility. These risks play significant roles in African affairs and are likely to do so in the future.

The price of political instability in Africa is reflected in high rates of crime, corruption, unemployment and disease. Overcoming these problems will only occur with better national governance, but it will not be quick. In the meantime, there is the potential for strategic, risk-savvy buyers to gain commercial advantages. M&A activity in Africa must be seen in this light.

The state of corruption

Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for a mere 2%-3% of global GDP and cross-border trade. However, Africa has the majority of the world’s unexploited natural resources, and its lack of development presents investment opportunities in telecommunications, banking and infrastructure.

The continent is not, however, a deal-free zone. South Africa has a highly developed financial system and its companies have enough capital to do large-scale M&A, especially in mining. The country also has two mobile phone companies that dominate the African market; both are active acquirers. Elsewhere in the region, strong commodities prices are creating an unprecedented number of M&A opportunities. This is especially true among African resource companies, primarily in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where a recent round of mining company mergers and takeovers has occurred. Meanwhile, high oil revenues and a recapitalised financial services sector have boosted M&A in Nigeria, especially in banking and telecommunications.

The region would be doing much better were it not for the bribery, corruption and absence of transparency that plagues so much of the continent, where key sectors of the economy are state-controlled. Corruption is particularly high in natural resources projects, where international companies often find themselves under pressure to bid for concessions with, or award contracts to, local companies linked to top government officials. In Nigeria, for example, a number of oil concessions have been granted to politically connected companies; this has led to controversy and, in some cases, cancelled awards. Angola, for its part, has a rapidly expanding oil- and mining-based economy, but widely reported links between the country’s political and business elites makes the choice of local partner a sensitive matter for outside investors.

The best-known data source on global corruption is Transparency International’s (TI) annual index, which ranks countries according to perceptions of corruption. Another TI publication, the Bribe Payers Index, should be required reading for all investors in the developing world; it serves as a reminder that it takes two sides to make a corrupt deal.

Key people challenges when acquiring in emerging markets

1. Fast-tracking high performers

There is immense untapped talent on the African continent. The challenge is to create sustainable, accelerated career development programmes for the high performers. Failure to do so will restrict business growth opportunities.

2. Attracting and retaining key talent

The need for self-funded and meaningful short-, medium- and long-term employee incentive schemes is becoming evident. Employers are regularly expected to compete for and retain skills on a “weak” currency base against major currencies.

3. Total rewards (Compensation, benefits, careers):

Companies entering new markets may need to apply a different profile of the workforce. An employer’s Total Rewards strategy must drive performance and simultaneously attract and retain the required talent to meet future business priorities at an affordable and sustainable cost.

The underlying theme in successful M&A transactions in Africa is to rapidly migrate from mere administrative/transactional HR departments to business partners of strategic importance on the deal team.

Dealing out the personal touch

Risk and potential reward must be understood in the present and forseeable future

There is a tendency for industries on the continent to support HR programmes that are common to all companies in those industries yet different from those found in other industries. The reason for this is that multiple-employer institutions have been established to facilitate both the financing and delivery of these HR programmes for employers in a given industry. The greatest programme commonality is found in the energy sector, with pharmaceutical companies beginning to follow this model.

Economic impact

Both a country’s economy and its government will have a clear impact on the workforce, and security is a major concern in many African countries. In Nigeria, for example, armed attacks and the kidnapping of oil company employees have occurred with disturbing regularity. Several large multinationals have established guarded compounds for employees, especially expatriates, to deal with the security problem. Employee turnover, on the other hand, is low due to a scarcity of employment opportunities for indigenous personnel. Training and development, especially for middle management positions, is a key task for companies in Africa.

Risk is not the only challenge faced by acquirers in Africa. In many cases, they must deal with a lack of credible data on employee and benefit-compensation structures. Hiring and retaining talented people is often expensive, due to security concerns and a lack of access to modern medical facilities. Nevertheless, investors are being attracted into the region, which has an abundance of natural resources needed by the developed world.

Middle East

Overall, respondents consider the Middle East to be the second-riskiest region of those in the survey, but on a number of specific risks it scored slightly better, although by no means well. But it is a disparate region, encompassing countries with relatively good business environments and those with extremely poor conditions for foreign investors. In general, however, the trend towards liberalisation of state-owned industries and the reduction of trade barriers is encouraging greater levels of investment.

By far the leading concern in this area is political risk, with a score of five, exceeded only by Africa.

Respondents also highlight organisational cultural differences as being another notable risk factor. This risk scores five out of a possible ten – higher than any region in the survey apart from China, India and South East Asia. The large extent to which wealth in much of the region remains in family companies may partly explain this perception. This structural phenomenon can also be a powerful barrier to M&A, as families will retain strong voting rights that prevent takeover.

Although the proportion of businesses that are family-owned in the Middle East is similar to that in Asia, or even Italy and Spain, there is a key difference in terms of the size of those family companies. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development reports that the 20 largest companies in each of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco and most of the Gulf States are family-owned. The role of a minority investor in such a situation presents obvious challenges.

While political risk and organisational cultural differences in the Middle East are certainly a concern, other factors are less problematic. For example, infrastructure, currency instability and problems with the intellectual property regime attract lower scores than in most other emerging market regions. Written by the Economist Intelligence Unit

Aside from investors within the region, there are strong appetites for investing in the Middle East from respondents in Asia-Pacific, suggesting that the desire to build a “new Silk Road” is strong.

Bridging the gulf

The past few years have seen the rise of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs): state-owned investment bodies with enormous assets and interests around the world. As the sub-prime crisis broke, their influence became clear. The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, the largest SWF of them all, with estimated assets of some $1.2trn, quietly injected $7.5bn into Citigroup’s deflated balance sheet, which will convert into a 4.9% equity stake. The Kuwait Investment Authority extended a further $3bn to Citigroup and $2bn to Merrill Lynch in return for three-year convertible paper.

But they have not had things all their own way. In 2006, in the face of opposition from US lawmakers, Dubai-government-owned Dubai Ports World gave up control of the US ports it had bought through its acquisition of the UK’s P&O. Early in 2007, other Dubai-owned investment vehicles saw attempts to buy New Zealand’s Auckland International Airport and OMX, the northern European bourse operator, stymied on political grounds.

While the sub-prime crisis may have encouraged the West to turn a blind eye, once the panic has passed the issues will return. In the Gulf, the SWFs have some $2trn of assets and, with oil prices and production at current levels, they are continuing to generate massive cash surpluses. European assets offer diversification but, given that Gulf SWFs’ currencies are pegged directly to the dollar, also look expensive. US assets feel attractively priced but are potentially politically more charged. So it is no surprise that an increasing asset allocation is being diverted East rather than West. Swelling liquidity is encouraging the Gulf SWFs to look at ever larger transactions, which are easier to find in the US and Europe, and an appreciation of the comparative comfort of mature markets has been sustained.

The debate has some way to run and a collision appears increasingly likely. Both sides need some education. Politicians, business leaders and the media in the West need to work harder to understand the SWFs, the governments that control them and the political economy that underpins them. Equally, the Gulf’s SWFs may need to work a little harder to explain their agenda and demonstrate their long history of political independence in their investments.

Realities and risk management in the Middle East

In many countries in the Middle East, the divide between Sunni and Shiite has become ever more apparent. This has enabled critics to claim that a powerful Iranian-led Shiite strategic entity has emerged, giving rise to a fear in many Sunni-dominated Arab states about what this may mean for them.

The potential for sectarian unrest and change in the region’s strategic balance has resulted in the realisation by many states of the need for a rapprochement with Iran. This has been illustrated most notably by the Arab countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – which groups Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – building trade relations with Tehran and charting an economic course with a potential for mending ties. With as many as 500,000 Iranian expatriates now living in the United Arab Emirates, for example, and about 10,000 part-Iranian-owned firms, it is not surprising that Iran is the main destination for exports from Dubai.

The new geopolitical alignments, coupled with the traditional animosities, especially over the Palestinians, make for a volatile region. They also make one that can both deter foreign investment and bring new opportunities. The defence sector has long attracted Western interest but, in recent years, so have the construction and financial sectors in particular. In return, investment by Arab countries in the Western financial system has brought the two regions’ brokers together.

Businesses should focus on seizing M&A opportunities as they arise, while ensuring that appropriate risk-based due diligence is conducted not just in the political risk arena but also in the economic, societal and strategic risk environments. Additionally business and risk management plans need to be put in place that can cater for a sudden and unexpected turn in events. Adopting this “best-in-class” approach to risk assessment will derive competitive advantage, manage volatility, instil stakeholder confidence and protect the tangible and intangible assets of the business.

In recognition of the potential for volatility of the region, companies in the Middle East have generally been receptive to the idea of embedding best-practice risk management into business routine. This is particularly true for the highly regulated sectors of energy, financial services, telecommunications and construction markets in the Gulf Region – many are looking at how to adopt a more focused approach to risk management in their business planning. The markets for these services are substantial, with enormous increases in demand, so the consequences of disruption are widespread and systemic. Thus, organisations looking towards the region as a target for investment or acquisition can, over time, expect to receive a positive response to questions on the quality of risk management capability. In the interim there is no substitute to ensuring that not only financial due diligence is conducted but also a risk management-based assessment looking at exposures that could prevent the achievement of target company objectives, projected rates of return or exit strategies.

Human capital issues in the Middle East

The level of external investment in Middle Eastern countries continues to grow, despite a moderately high level of perceived risk, as member countries become more open to globalisation, make business dealings more transparent and modernise their capital markets. And there is certainly plenty of capital in some Middle Eastern organisations to finance deals. Turkey, for example, has been the destination for some of the major private equity firms in the past few years.

Companies interested in M&A in the Middle East should be prepared for challenges on the people side of their transactions. These include the following:

- There is a shortage of senior managers, which has produced a merry-go-round of talent and, in many cases, a bidding-up of executive compensation. The rise of transactions in this region in the past three years has exacerbated the talent shortage. At the same time, executives who have the skill and experience to develop and implement M&A strategy may not be familiar with the people issues inherent in business transactions.

- Reliable labour market data is in short supply in all sectors – and at all levels of employment – limiting the ability of acquirers to evaluate the workforce of potential targets.

- Organisational cultural differences exist between domestic Middle Eastern companies and those that have a broader multinational reach and perspective, making integration even more complex and uncertain.

A “best-in-class” approach to risk assessment can manage volatility, instil stakeholder confidence and protect the tangible and intangible assets of the business.

China, India, South East Asia

The countries in this diverse group currently attract more interest from overseas investors than anywhere else in the world, but while the potential rewards are certainly significant, so too are the risks.

The risk profile of this region exceeds that of much of the developing world across a range of measures. Respondents from within the Asia-Pacific region itself are more likely than those from elsewhere to rate these countries as risky on every detailed measure except – understandably enough – unfamiliarity of organisational culture.

By aggregate measures, the area scores as the second- or third-riskiest in the survey. When asked about specific risks, respondents scored this region most highly for:

- problems with red tape/bureaucracy;

- protectionist sentiment;

- organisational cultural differences;

- problems with intellectual property regime; and

- environmental liabilities – known and unknown.

Intellectual property risk has long been a concern in the region, especially in China, although the country’s accession to the World Trade Organisation may go a long way towards reducing the problem. The gradual opening up of sectors such as domestic commerce, financial services, insurance and tourism is underway. Geographical restrictions on where foreign companies are allowed to set up operations will also be relaxed in the next few years. Despite this trend, concerns about the operating environment are likely to linger for some years. For example, environmental liabilities in a region that is experiencing rapid industrial and economic growth can be considerable, while problems with red tape and bureaucracy, although easing slightly as businesses and governments become more efficient, will take many years to fully unravel.

India’s potential to attract increased FDI inflows is vast, although poor infrastructure, bureaucratic challenges and interdepartmental wrangling will slow the pace of opening in many sectors. The infrastructure, energy, telecoms, information technology and insurance sectors are likely to be the main magnets for FDI. Producers and assemblers of cars and automotive components are also re-evaluating India’s potential, as are biotechnology firms. The skilled, English-speaking workforce has been a significant attraction for investment, particularly in the IT sector.

When this group of countries does not achieve the highest score for a particular risk category, it either ranks second or third when compared with other regions. The only risk for which the region attracts a score of less than four out of ten is litigation culture. There is simply no risk that is considered low in these countries compared to other parts of the world.

Despite the perceived risks of investing in this region, the massive level of M&A flow suggests that the expected reward is much stronger. We are witnessing a fundamental realignment of the global business landscape, with companies all around the world eyeing the huge potential of these countries and ramping up their investment and presence accordingly. Whereas previously, investments made in these countries tended to be resource-based to take advantage of inexpensive labour, today they are more likely to be made on the basis of the growing spending power of the huge populations in these countries. Written by the Economist Intelligence Unit

Appetites for investing in this region are strong throughout the world. No other region attracts such widespread interest.

Keeping it in the family

Asia is undergoing fundamental change, driven by enormous socio-economic development in China and India in particular.

Traditionally, much of the wealth creation in Asia has been linked to large family-controlled conglomerates. Successful family companies combined entrepreneurship and an understanding of the links between political and economic power to amass enormous wealth.

The transfer of stewardship of these conglomerates from the founding generation to the next is generating new challenges for Asia’s dynastic families. It also offers significant opportunities for international investors as conglomerates are restructured to make more efficient use of their capital.

Scions of Asia’s tycoons are often educated abroad and are comfortable with Western business practices and standards. They are keen to engage the help of professional management as well as to tap into international capital, both to provide fresh funds for the next phase of business development and to access the international standards of corporate governance that normally accompany such investment.

While the opportunities in Asia are significant, international investors, be they private equity firms, portfolio managers or corporations, need to be attuned to the risks associated with investing in or acquiring from a family-controlled conglomerate. These risks include a clear understanding of the role the family plays throughout the business empire, including the importance of political connections within the business operations and the extent to which a company may be adversely affected by such issues as weak intellectual property regimes, rapidly changing environmental regulations and liabilities untraceable through public records. Thorough research and due diligence are fundamental to understanding the risks inherent in such investments.

The introduction of Western standards of corporate governance into an Asian conglomerate needs to be handled sensitively. Successful acquirers have combined new governance and accounting practices with the traditional Asian values of corporate identity and pride and trust of management.

A Sino-Indian talent crunch

In China, where relationships count for so much, acquirers must focus on maintaining relationships in the post-close period. Losing important relationships with customers, suppliers and government regulators can destroy the deal’s value.

Perhaps the best way to keep those relationships intact is to retain competent pre-deal talent and provide clear incentives to succeed. Talent retention, however, is not easy in China’s booming economy. Good managers and technical professionals enjoy tremendous mobility. In 2007, for example, the turnover rate among young professionals (ages 25-35) was a startling 67%. As domestic companies have caught up with multinationals in terms of total rewards (compensation, benefits and careers), foreign enterprises need to manage their talent with more care and attention than ever before.

The most effective talent-retention vehicles are:

- individualised career development plans;

- competitive pay;

- overseas assignments;

- training programmes; and

- improved communication between managers and employees.

Westerners who enter the Chinese market for business ownership should also be prepared for eye-popping wage inflation, which is about 10% and even more for highly skilled employees. With those wage rate increases, China is likely to lose its low-cost wage advantage over the next three or four years.

India offers a contrasting case on the wage front. Like its larger neighbour, India faces a talent shortfall despite its capacity to turn out technically trained people. In the IT sector alone, a shortfall of half a million professionals is forecast by 2010. Nevertheless, a Mercer report, China & India: Comparative HR Advantages, released in February 2007 indicates that compensation in India is significantly lower than in China, and variable pay is more common for all Indian job positions surveyed. Many Indian organisations in sectors such as IT, financial services, insurance, civil aviation, automotive and infrastructure – the so-called sunrise industries that have seen growth in excess of 20% to 30% over the past few years – are taking initiatives to address potential talent shortages. These include:

- increased spending on employee capability development;

- hiring from alternative channels (for example, hiring high school graduates with vocational training in lieu of engineers, and training them in software development, etc.);

- recruiting from so-called Tier 2 cities such as Baroda, Chandigarh, Pune, Coimbatore, Trivandrum and Jaipur to ensure employee engagement and productivity at lower costs; and

- using variable pay (including bonus plans, stock options and long-term incentives) to counter continually rising wages.

The recent Mercer Asia-Pacific Total Rewards Survey 2007 found that India’s young workforce, although demanding higher salaries, is increasingly attracted to organisations that offer career growth opportunities and “role models” at higher organisational levels. Given the rapidly developing markets, the latter point has encouraged organisations to give upward-moving managers a fair degree of training in management and leadership skills.

Has the tide turned for polluters in Asia?

Hardly a day goes by that the environmental problems in Asia fail to make international news. Headline stories have included the potential impact of poor air quality on the forthcoming Beijing Olympics, Asian exports that have been recalled as a result of product contamination, and several major industrial incidents that have severely polluted the environment. What companies may fail to realise is that this publicity, together with an increasingly vociferous green lobby, is driving rapid and sweeping environmental regulatory changes, which, if ignored, pose a serious threat to the performance of businesses in the region.

The Chinese government has introduced a raft of measures designed to improve environmental quality.

Product recalls are hugely expensive for companies and can damage their reputations

While the degree of environmental litigation and statutory enforcement in China still lags well behind North America and Europe, companies are now seeing much greater regulatory scrutiny of their operations and stricter enforcement of environmental legislation, particularly in the richer Chinese provinces and prefectures.

With over 2,000 environmental, health and safety regulations, achieving full compliance with any real certainty is a major challenge. But it is a challenge that should be taken seriously. Several firms have been shut down in recent months on environmental grounds. Companies face greater financial penalties, with higher fines proposed for firms found liable for water pollution incidents. Companies look set to bear 20% to 30% of the direct economic costs of an incident and all of the costs for containment and clean-up.

Under the “green credit policy”, firms that fail to pass an environmental assessment or implement China’s environmental protection regulations may be disqualified from receiving loans from any financial institution. Companies that have already obtained loans but are later discovered to have violated the environmental regulations may have to return their loans. The Chinese government may also involve the financial sector yet further in its environmental plans if it goes ahead with a compulsory environmental impairment liability insurance programme.

Greater environmental awareness in China has spawned increasingly active non-governmental organisations such as the Beijing-based Institute of Public and Environment Affairs (IPEA), which frequently names and shames companies for alleged environmental violations.

Foreign businesses looking to invest in the region should be particularly mindful of the evolving legislative landscape and the environmental liabilities they may assume in a merger or acquisition.

Manufacturing and the quality fade

As China and India continue their ascents as manufacturing giants, acquirers that target the region’s manufacturing sector should exercise greater caution. They could find themselves on the wrong end of costly product recalls. During the first half of 2007 alone, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission issued 152 product recalls, 68% of which involved items made in China. Those recalls were costly, both for the Western brands that outsourced the manufacturing and also for owners of the Asian contract manufacturers that shipped the sub-standard goods.

Quality breakdowns are often a result of “quality fade”. Quality fade occurs when financially strapped factories take short-cuts to reduce their operating costs and improve profit margins. Here’s how it works. A product company creates specifications for the design, regulatory compliance and safety of a toy, appliance or other item. Those “specs” are then incorporated into a contract and purchase order with a manufacturer. Typically, the first production samples supplied by manufacturers are made in strict accordance with contract specifications. Everything appears up to spec. However, the manufacturer cuts corners to reduce costs during successive production runs without notifying the customer, and the customer does not conduct sufficient independent product testing to notice subtle and progressive changes in the product. The result in some cases is an unsafe product – and a product recall.

Product recalls, on average, are hugely expensive for companies and their reputations. The question is: how can companies involved in M&A transactions in Asia protect themselves? They can do so by requiring process change protocols, a subset of Six Sigma manufacturing techniques. Process change protocol procedures should detail the analysis and documentation that are necessary for a supplier to make changes to the materials they are using in production. Changes to a supplied material should be defined as: alterations to the product itself; alterations to the method of manufacturing or packaging; or the manufacturing location.

Alterations should also be classified as process, design, source and engineering or deviation change requests. Changes should be based on the most adverse effect created in the processing of the material or in its handling or foreseeable use. If this process is created with attention to the chain of command for early notification and the approval process, fewer product recalls will occur due to quality fade.

Keeping an eye on the prize

Firms have different reasons for conducting due diligence and the depth of work undertaken varies widely. Companies give different levels of value and criticality to the due diligence process, resulting in varying levels and quality of reports obtained – each one can answer certain questions, but very often shortchanging the due diligence process brings significant risk of issues getting missed.

A basic screening report that looks at public records merely demonstrates that a company conducted due diligence. The reports can catch glaring issues such as an outstanding criminal warrant, but because they only look at the name matches of subjects, they can be incomplete when faced with common or high-profile subject names. Therefore they often provide a false sense of comfort and raise more questions than they answer.

The red flag report offers a more balanced view and is used by clients that conduct several due diligence investigations over time. The reports use an investigative methodology and the findings are thoroughly analysed to get a better understanding of potential issues and areas that may require further investigation.

For firms entering transactions in emerging markets, in-depth due diligence is a must because the availability and quality of public records varies tremendously. In the Middle East, for example, public records are essentially non-existent, so the key to successful transactions is relationships. Consequently, thorough due diligence calls for a much deeper understanding of the key relationships and abilities of the individuals involved.

Australia, Japan, Korea

As a group, these developed countries in the Asia-Pacific region are perceived as the safest investment destinations, with few respondents considering either the overall environment or any particular issue to be cause for concern. The only notable risks are protectionist sentiment and organisational cultural differences, although the extent to which these and other risks are a problem will vary from country to country, given their heterogeneity in terms of business environment and culture.

Appetites for cross-border M&A flows into Australia remain strong, despite recent setbacks with deals, such as the collapse of the bid by a private equity consortium for Qantas, the national airline, and the withdrawal by another consortium from a battle for Coles, a grocery retailer. The country’s resources sector remains a likely source of deals, with dozens of mid-sized companies in sectors such as mining and power and utilities seeking domestic mergers to protect themselves from resource-hungry companies from countries such as China and Russia.

In South Korea, 2007 was a record year for M&A deals, with activity reaching US$73.8bn, according to Thomson Financial. The coming years are also expected to see relatively strong transaction volumes as the government continues its policy of selling stakes in recently restructured companies. In early March, for example, creditors in South Korea agreed to accelerate the sale of Hyundai Engineering & Construction, which is likely to result in one of the biggest M&A deals in the country this year.

Despite this positive outlook, a number of factors continue to deter large-scale foreign investment, including residual hostility towards foreign ownership of South Korean assets on the part of ordinary South Koreans; the continued lack of corporate transparency; and, particularly since early 2003, increased labour militancy.

Investment, however, is about reward as well as risk. Although South Korea’s economy grew at 4.8% per year between 2002 and 2006, and Australia’s at a lower but still respectable 3.3%, GDP growth in Japan, the world’s second-largest economy, averaged just 1.7% in the same period. The country continues to recover from the disastrous post-bubble correction of the 1990s, but progress has been slow. Moreover, the Japanese have dubbed last year “the year of deception”: the stock market fell by 10% and recently the authorities even had to revise down announced GDP growth figures from 2.1% to 1.3%. Those considering Japan as an investment destination will need confidence in the available rewards to take advantage of the low-risk environment there. Written by the Economist Intelligence Unit

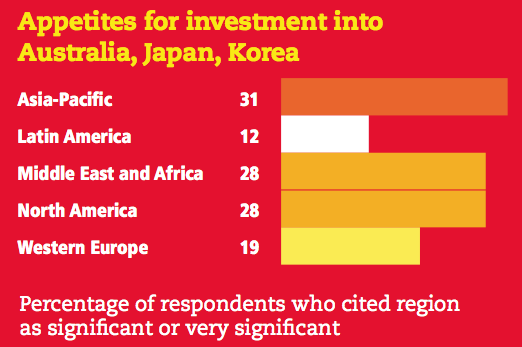

Appetites for investing in the countries of developed Asia are less strong than those for investing in developing Asia, although interest from outside the region is most likely to come from Middle East and Africa and from North America.

Japan’s new deal for investors

Japan opened a wide door to foreign investors in 2007 with its revision of a major piece of regulatory legislation. In so-called triangular mergers, the law makes it possible for foreign-owned companies to invest in Japanese companies by means of stock-for-stock exchanges with the Japanese subsidiaries of those companies. Coupled with the country’s low interest rates, a favourable financing condition has ensued, attracting more foreign investors to Japan’s energetic M&A market.

Disclosure and clarity

Japan’s evolving regulatory environment brings greater disclosure and clarity to what had been a murky financial arena. The Financial Instruments and Exchange Law (the Law) was enacted in 2006, with the primary objective of bringing the country’s financial markets into conformity with global standards. Often referred to as J-SOX, the Law aims to protect retail investors, improve the efficiency of product offerings, and enhance market accessibility and functionality. In so doing, it should serve to create greater confidence among investors, both foreign and domestic, with the aim of attracting more equity capital to the Japanese securities market.

Beginning in April 2008, the Law makes financial reporting of “internal control” compulsory for stock-listed companies. For investors, this requirement will enhance transparency and clarity with respect to the financial projections, risks and potential losses associated with target companies. The Law stipulates four core objectives for internal control: operational effectiveness and efficiency, reliability of financial reporting, compliance with applicable laws and regulations, and safeguarding of assets.

In an M&A scenario, accurate valuation of the target company’s business and assets would be a required under “safeguarding of assets”. This not only means protection of physical assets, but extends to proper and accountable acquisition or disposal of tangible and intangible assets: real estate, intellectual property, human resources, liabilities and risk are all within its scope.

The “safeguarding of assets” requirement applies to all interested parties – in this case, to the business owner (or seller) and to the potential purchaser. Therefore, both undervaluation of a target by investors and overvaluation by sellers are unacceptable under the Law. Consequently, financial evaluation should verify all factors that could affect the true value of a target business. Projected financial profitability and loss are the obvious areas of concern, but the risk exposure of the target businesses should not be overlooked, as it could have a major financial impact if risk were to materialise as a loss. Risk categories can be many, depending on the company – trade credit, a long-tailed environmental liability and product liability, to name but a few.

The regulation environment

Anyone contemplating an investment in Japan should welcome these regulations. The Law will bring investors fairer deals and the information they need to make informed decisions. Knowing the risk environment that surrounds acquisition targets, thanks to risk due diligence, can help investors make wiser choices.

Employee well-being and Japanese M&A success

Japan has become one of M&A’s hot spots, with funds from the United States, Europe and domestic corporations fanning the flames. Foreign deal makers improve the odds of success here when they recognise important facts about the people side of organisations. Foremost among these is that the Japanese workplace is as much a social as an economic enterprise. A transaction that threatens that social system – such as a lay-off – is likely to create resistance, particularly when the buyer is non-Japanese.

Coping with human capital risk in Japan

A second point for outsiders to recognise is that Japanese organisational culture values the well-being of employees as much as that of shareholders. Acquisitions made over the objections of employees and other stakeholders could face post-deal resistance on the work floor. The way to overcome resistance, by both corporate leaders and employees, is for the acquirer to demonstrate the value of the transaction to all parties, including employees. Unless a deal can demonstrate benefits from restructuring, genuine synergies, the addition of new technology or some other value, it might struggle to generate employee support. While post-deal profitability is the universal measure of M&A success, employee morale and engagement are also key measures of success in Japan.

Deal makers should also take into consideration that Japan has an ageing population and the lowest birth rate among industrial countries. In line with this, official projections describe a population decline of 21% during the next 50 years (from roughly 132 million to 105 million).

The ageing population will impact the labour markets, consumption and the stock market. Population decline also has important implications for corporate human resources in Japan.

Planning for compensation in Australia

Organisations considering an Australian acquisition should know that the employee health and safety obligations they will inherit, in addition to compensation costs for injured workers, may be major factors in compliance and valuation.

Further, variation in the laws of Australia’s eight states and territories make analysis, measurement and treatment of workers’ compensation a challenge for In high-risk employment categories, the total cost of risk for workers’ compensation can be significant would-be acquirers. Safety practices, accident frequency rates, claims costs and related factors have an impact on the cost of insuring for workers’ compensation and, ultimately, on EBITDA and the valuation of the target company. Key features of this complex system include workers’ compensation and statutory schemes.

Statutory schemes mainly have cost calculation models that use gazetted classification rates by industry, with actuarial loading factors to project final cost of claims. In underwritten states, guidance rates are issued by the Regulatory Agency; licensed insurers, however, have the flexibility to determine final pricing for individual employers.

While all jurisdictions provide for costs of medical treatment and lost wages, some provide a schedule of payments for certain degrees of injury; others allow common-law claims for pain and suffering. Individual jurisdictions are increasingly grouping related companies for the purposes of premium calculation. Most jurisdictions allow large, financially secure employers to obtain self-insurance licenses.

In high-risk employment categories such as mining, construction, natural resource extraction and heavy engineering, the total cost of risk for workers’ compensation can be significant. This is particularly true in statutory states with fixed-cost models; substantial changes in workers’ compensation premiums can occur in these jurisdictions within a one-year period.

Workers’ compensation can create unique challenges or scenarios for an M&A transaction, including the following:

- Acquiring an organisation that is a “carve out” from a business that has a workers’ compensation self-insurance licence. In effect, the target will lose the benefits of having access to the self-insurance provided by its parent company. In lieu of self-insurance, the acquirer must factor the costs of conventional statutory insurance into its financial model.

- A cost/benefit study of the target becoming self-insured, including the time frame for achieving a self-insurance licence. Such a strategy can, over the lifetime of an investment, produce significant bottom-line benefits.

- Projecting likely future workers’ compensation costs when the target has an adverse claims history, for both the target’s costs and, if applicable, the purchaser’s costs if it has other businesses in Australia.

- Assessing potential cost reductions through workforce risk management strategies. We have seen companies trim up to 30% of the workers’ compensation costs through such strategies. An acquirer must, naturally, go beyond development of strategies; it must also plan for post-acquisition implementation.

The cost of employee health and safety and workers’ compensation is substantial for many businesses. Effective due diligence can help an acquirer construct a picture of this cost and create an effective plan for managing it going forward.

Eastern Europe

Survey respondents perceive Eastern Europe’s risk environment to be halfway between the developed and developing worlds. It scores notably better than any other region in the latter group, but rarely attains the same levels as the former, despite the European Union membership of many of these countries. Overall, the results bode relatively well for future investment, in particular from Western Europe.

Eastern Europe is gradually emerging as an attractive region in which to seek M&A targets. In 2006, the region displaced Latin America and the Caribbean as the second-most-important emerging market destination for FDI after developing Asia. Large-scale privatisation within many countries, along with growing confidence among acquirers as the result of EU expansion, should continue to drive transactions within the region.

No specific risk stands out as high. Nevertheless, a significant number of issues do require more attention if Eastern Europe wants to have a risk profile similar to those of its Western neighbours and other developed states (see chart).

Most of these factors, however, should improve over time, especially for the European Union member states, where intellectual property, corporate governance and risk management regulations have already converged with those of their Western neighbours, and where EU funds are likely to help with infrastructure.

Moreover, in the case of some risks, Eastern Europe has more than caught up with wealthier regions, according to respondents. On cultural issues, it scores better than North America, largely because of the divergence in concern towards attitudes on litigation. In addition, protectionist sentiment and workforce inflexibility were seen as less of a worry than in Western Europe. These sentiments reflect a pro-business approach in the region that has also manifested itself in areas such as the widespread experimentation with flat taxes. Written by the Economist Intelligence Unit

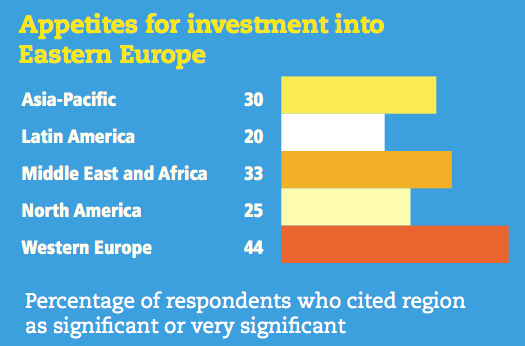

Fast-developing Eastern Europe attracts strong appetites for investment from Western Europe. There also appears to be interest in building links among respondents from Middle East and Africa.

Operating outside the comfort zone

Central Eastern Europe (CEE) is perceived by many as one of the most fertile areas of investment opportunity. Confidence in the region is strong among both domestic corporations and multinationals contemplating investments.

Multinational corporations are often more cautious in their initial CEE forays than they are in making US or Western European deals, but this caution is not particular to CEE; unfamiliarity can make even the most straightforward venture seem risky. For a domestic acquisition, a company is often comfortable with receiving a level of warranty and indemnity recourse from the seller that is significantly below the overall transaction price, particularly in jurisdictions where aggressive auctions are prevalent. A first-time acquirer in the CEE, however, may think again when a seller offers limited financial recourse against a possible breach of a warranty or indemnity. The buyer in those cases may assess available options and conclude that:

- Recourse is so limited that the deal cannot be completed;

- It could be comfortable with the level of financial recourse, but only if the transaction price were reduced commensurately; or

- Alternative mechanisms of recourse are available.

Pressure to make an acquisition in a region perceived as “hot”, such as CEE, can influence deal makers to view completion as an absolute must. Reducing the offering prices – particularly in M&A hotspots such as financial services, technology, media and telecommunications – can eliminate an acquirer as a viable bidder. In those cases, a corporate buyer must seek alternative ways of obtaining the financial recourse that it would otherwise receive from the seller. Most corporate acquirers struggle to find an alternative method of risk mitigation.

However, many sophisticated deal makers accept the limited financial recourse offered by sellers and obtain additional recourse from third-party insurers in the form of a warranty and indemnity insurance policy. The insurance policy is triggered if and when sellers breach their warranties or indemnities; and will respond once the seller’s financial cap has been extinguished. This type of solution will have the added benefit of allaying concerns over the strength of a seller’s balance sheet, and ultimate ability to rely on the warranty recourse mechanism.

For most corporate acquirers, the most comfortable position from a risk mitigation perspective occurs when a financially strong seller provides warranties across a broad spectrum of topics and caps its liability at an amount acceptable to the buyer. This may not always be achievable or, indeed, commercially feasible in a region as competitive as CEE. However, corporate investors armed with the full range of M&A tools can often achieve successful outcomes.

Unfamiliarity can make even the most straightforward venture seem risky

Workforce behaviours in old and new Europe

Deal makers who venture into CEE (or the EE zone, if we include Russia, the CIS and Turkey) face a number of human capital issues typically not found in the West. For starters, businesspeople from outside the region are seldom familiar with the structure of its organisations (newly privatised, family-owned, etc.), area labour laws, the relative ease of restructuring and workforce skills and experience (especially managerial).

In terms of due diligence, buyers in the region also face a lack of data depth and transparency. In CEE countries that have already joined the EU – for example, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland – data is as good as that found in the West, although historical data is generally less reliable. In Russia and ex-CIS countries such as Ukraine, however, data may be difficult to obtain, and what can be obtained may not be reliable. There are also problems with “phantom” staff, off-the-book payments and other irregularities. Each of these requires attention if the full confidence of outside investors is to be gained.

Acquirers should also understand the pros and cons of the region’s workforce. Employees accustomed to the old Eastern bloc practices may have difficulty adapting to a Western workplace. On the plus side, however, many younger workers are well-educated, have good English language skills, are hungry to learn and succeed, and carry less workforce “baggage” than their Western counterparts.

Post-deal integration challenges the acquirer on several HR fronts. First, modern performance management strategies (let alone systems) are rare. Few workers have any experience with a culture of employee empowerment and performance-aligned rewards – the type of culture that encourages commitment, continual improvement and high productivity. Most workers, especially older ones, have been accustomed to command-and-control management. Skill shortages can also create post-deal problems. Talent poaching in the wake of transactions has been observable, particularly in the banking sectors of Russia and Ukraine.

Many younger workers are well-educated, have good English language skills, are hungry to learn and succeed, and carry less workforce “baggage” than their Western counterparts

Western Europe

Overall, Western Europe is regarded as one of the world’s safest investment destinations, with two-thirds rating the risk environment there as having low or very low severity.

The trend for cross-border M&A in the region has been underpinned by relatively low interest rates, the competitive pressures for restructuring and consolidation and the increasing sophistication of financial markets. Some of the world’s largest recent cross-border deals have been between European companies, including the acquisition of Scottish Power by the Spanish utility Iberdrola for US$28.9bn in 2007, and the acquisition of the Spanish energy company Endesa by the Italian utility Enel for US$11bn. Deals are also reaching down into the mid-sized sector – the German Mittelstand, for example, where companies are predominantly family-owned, is starting to become more acquisitive after years of shunning M&A.

The region nevertheless has several issues that raise concerns. The most striking is protectionism, which scores four on the risk chart and is only exceeded by China, India and South East Asia. Although the French government is often singled out as a perpetrator of this problem, whether for making patriotic statements about French industry or for its broad use of the concept of strategic industries (such as to protect yoghurt maker Danone from PepsiCo), other European states are no strangers to preventing foreign takeovers. In recent years, for example, Spanish governments have been quite willing to support the idea of “national champions” in given industries and the German government (now that the European courts have struck down its “VW law”, which effectively prevented VW being bought) is looking at ways to revive at least parts of the law – much to the consternation of Porsche, which owns 31% of the company and is seeking to raise its stake.

Some of the world’s largest recent cross-border deals have been between European companies

Unfamiliar or restrictive workplace laws also score highly for Western Europe. The combination of employee protection, relatively high employment taxes and social payments, which together constitute the European Social Model, continue to deter would-be investors. And despite attempts to modify these laws in recent years, the status quo has strong defenders among some politicians in leading EU states – notably Germany, France and Italy.

Similarly, the EU has developed the most progressive, or indeed stringent, approaches to quantifying the value of environmental liabilities for which organisations are accountable. The Environmental Liabilities Directive, which came into force in 2007, enshrines a “polluter pays” principle, which means that whoever caused the damage will be held liable.