Publications Lost in Translation – Avoiding Misadventure in Cross-border M&A

- Publications

Lost in Translation – Avoiding Misadventure in Cross-border M&A

- Bea

SHARE:

By Caroline Firstbrook – Accenture

More and more companies are looking abroad for acquisition targets or merger partners to help them meet their growth aspirations. While transnational deals are not uniquely prone to disaster, they do offer a different mix of opportunities and risks, which need to be understood and managed if the deals are to be successful.

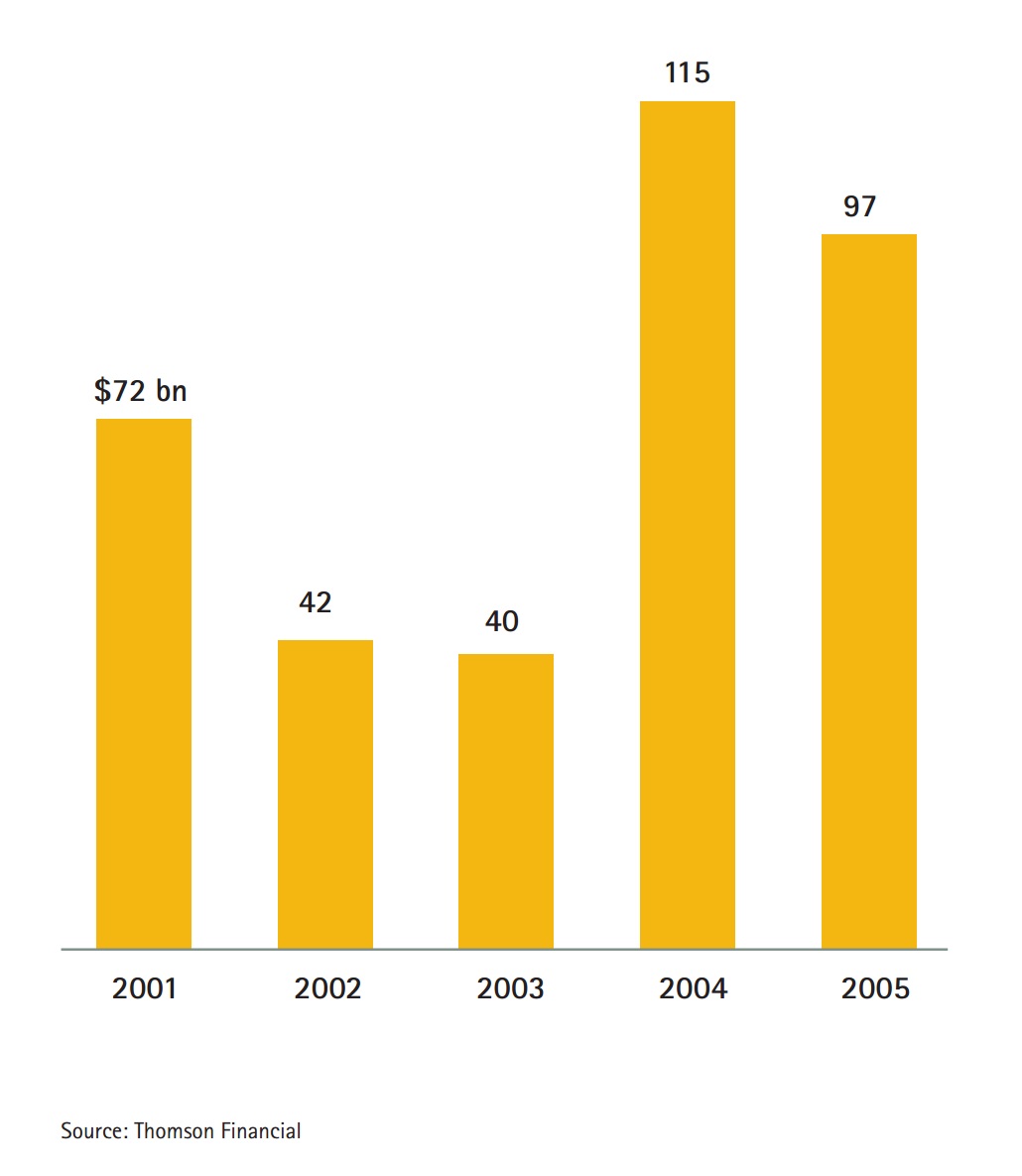

Cross-border M&A activity is booming. In 2005, Europe saw a 58 percent surge in transnational deals; in Japan, cross-border M&A jumped 21 percent, and in India the rise was a staggering 68 percent.

It’s not hard to see why. After years of restructuring, companies are once again cash-rich and confident. Credit is cheap and plentiful. And as industry consolidation reduces the number of viable M&A opportunities at home, more and more companies are looking abroad for acquisition targets or merger partners to help them meet their growth aspirations.

Yet for many, the prospect of acquiring or merging with a company in an unfamiliar market is daunting. Highly publicized fiascos in industries as diverse as automobiles, utilities and entertainment have contributed to a general perception that cross-border deals are a fast track to the destruc- tion of shareholder value.

Of course, transnational deals are not uniquely prone to disaster. There is a large body of evidence that mergers and acquisitions within national markets are more likely to destroy shareholder value than create it. However, cross-border deals offer a different mix of opportunities and risks, which need to be understood and managed if the deals are to be successful.

The pursuit of scale-based cost savings is usually the biggest driver for national deals. But cross-border acquisitions are more often about growth. Ready-made access to customers, products, brands, distribution channels and market knowledge all make acquisitions an appealing option for geographic expansion. Opportunities for revenue growth can arise from the cross selling of products, the exchange of knowledge about markets or technology, or the ability to offer existing customers more comprehensive global coverage. Moreover, when the market in question is developing rapidly, first movers have access to more and better deals than will be available for those that follow.

The key to success lies in understanding exactly what makes cross-border deal making different, and in develop-ing the skills needed to create value.

Accenture has identified four key drivers of success in cross-border M&A. They form part of a lifecycle approach that treats M&A as a holis- tic, integrated process and that is equally valid for national or cross- border deals (see “Mastering the art of value-capture in M&A,” Outlook, February 2005). They focus, however, on the very special risks and opportunities that accompany cross-border transactions.

1. Start with a clear and compelling strategy

The most successful cross-border acquirers begin with a clear view of both the role that cross-border acquisitions will play in their strategy and the type of companies best equipped to fill that role.

This clear strategic logic is well demonstrated by Heineken, one of the world’s leading brewers. Beer drinking in the United States and Western Europe, the Dutch company’s traditional markets, is declining as the population ages. But in much of Eastern Europe and Asia, younger people constitute a large and growing proportion of the population—hence Heineken’s recent spate of local brand, brewery and distribution network acquisitions east of the Elbe and in China. The company, moreover, buys only strong local brands and businesses that can support Heineken’s desired positioning as a premium brand in these markets.

Exel, a global provider of logistics solutions, offers another example of a company with a clear strategy for transnational acquisitions. As manufacturers increasingly operate on a global basis, they need suppliers with operations in all the places they do business, from production through sales. Between 1998 and 2004, Exel made more than 40 acquisitions in markets from Italy to Japan. These not only strengthened the company’s ability to offer integrated global logistics to its largest customers, it also gave Exel access to new cus- tomers, which could then be offered more comprehensive global service.

Overcoming barriers to entry and leapfrogging to a position of market strength was the driving logic for BP’s 2002 acquisition of Veba Oel and its Aral chain of gas stations across Germany and Eastern Europe. In addition to giving BP a leading position in this rapidly growing region, the deal also allowed the company to roll out its premium product and strengthen its brand position throughout Europe.

2. Do your homework

The greatest risks in cross-border transactions arise from the failure to understand the culture, regulatory structure or competitive environment—and sometimes all three considerations—in the target market. These oversights can lead to overly optimistic assumptions about revenue growth or cost-savings opportunities.

In many cases, acquiring companies assume that their detailed knowledge of their own market will translate directly to the target market, and they therefore see little reason to invest in upfront fact-finding. In other cases, where a market is undergoing rapid development, acquirers may decide that there is too much uncertainty for a detailed investigation of the current state of play to be relevant. Or if an acquirer feels pressure to act because a herd mentality takes over, it may decide there simply isn’t time to do its homework.

Whatever the reason, the failure to do homework on an acquisition can lead to costly mistakes. For example, when North American buyers fail to understand Europe’s different labor laws, they make overly optimistic savings projections from headcount reductions at the acquired company. Naïve reliance on the protection offered by contract or intellectual property law in some of the more chaotic developing markets can lead to significant write-offs or even the inadvertent creation of low-cost competitors that benefit from a company’s proprietary knowledge.

Assuming that customers in new markets are fundamentally the same as those at home is another classic mistake. A key driver in the 1998 acquisition of US carmaker Chrysler by Daimler-Benz of Germany was the assumption that product development costs for the joint company could be slashed by developing common models for both markets— an assumption that failed to recognize fundamental differences in road infrastructure, driving habits and customer preferences between Europe and North America.

Proper due diligence can expose these challenges and ensure that they are accurately reflected in synergy estimates and integration plans. The right level of investment in due diligence needs to be tailored to the specific situation. A straightforward investigation of local rules and regulations may be all that is required. But for more complex situations, local advisors who can help explain critical differences in customer needs, competitive behavior or cultural factors will typically repay the investment in their services many times over.

On the rebound

After falling off, cross-border M&A activity has bounced back sharply.

3. Value your new people

Regardless of the rationale for the acquisition, a key asset—many would argue the most important one—in a cross-border acquisition is people. Local market knowledge customer and supplier relationships, technical capabilities, and the influence and reputation of management with employees are all essential levers for extracting value from an acquisition.

The successful integration of an acquired management team requires sensitivity and careful attention to the cultural gaps that exist between acquirer and target, or between merging partners in a cross-border deal. Tolerance for uncertainty, attitudes toward power, cultural biases toward individualism versus collectivism, and preferences for how decisions are made differ widely across national boundaries. Companies that fail to recognize these differences can make costly mistakes that result in the loss of essential skills critical to future success.

Companies that get it right can accelerate the benefits resulting from cross-border acquisitions. Fans of Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Ice Cream, for example, feared that the culture of their favorite ice cream maker would be overwhelmed when Anglo-Dutch giant Unilever bought the company in 2000. But to the surprise of skeptics, Unilever very successfully blended its own culture with that of the boutique ice cream producer. The company maintained the smaller organization’s tradition of quirky new flavors (including Fossil Fuel Original, the Gobfather and Karamel Sutra), expanded distribution and launched new projects dear to the hearts of Ben & Jerry’s traditional customers, including an agricultural program in the Netherlands focused on establishing sustainable dairy farming practices.

The need to protect value in the acquisition has implications for the speed and degree of integration. In general, cross-border acquisitions offer fewer opportunities for cost reduction than national acquisitions, since they are not undertaken to achieve dramatic headcount reductions. Instead, the acquisitions are driven by an interest in gaining market access. Therefore, a light touch to integration, leaving the existing management team to get on with business as usual, may be the safest approach. However, if the acquisition is expected to provide an essential link in the delivery of global services, a faster and more comprehensive approach is needed. In these cases, high-quality execution is essential to minimize attrition in the integration process.

4. Execution, execution, execution

Successful execution begins early— in some cases, long before the deal is done. For example, Exel’s acquisition strategy has depended on the company’s ability to identify and court attractive smaller regional players, many of which were privately owned and whose criteria for selling were much broader than price alone. By entering early into a dialogue with these players, Exel has been able to shape deals that have met those criteria, improving the chances of retaining key management at the acquired companies and avoiding an expensive public sale.

Once a deal has been agreed to in principle, integration planning should begin as early as possible. It’s easy to underestimate the effort involved in any acquisition. Management from both sides are expected to guide a complex integration process in addition to carrying out their continued responsibilities for day-to-day operations. Without careful attention, critical sources of value, like existing customer relationships and distribution channels, are bound to fall through the cracks, with negative consequences for both the integration process and the day-to-day business of the merging companies.

Much hinges on the structuring of the teams tasked with merger integration. When BP bought Veba, an Integration Directorate team designed the overall program, planned all integration-related activities and then tracked their implementation across every relevant business. The challenge was to merge what were effectively three business cultures: Veba and Aral, which had only recently merged themselves; BP Germany; and the BP Group culture, which was to define the ethos of the new organization.

The team had to ensure that BP took operational control of Veba and its subsidiaries within two years, at the same time maintaining day-to-day business continuity and applying BP financial and operational policies across the new organization.

The directorate then had to actually implement new business practices. This involved monthly integration manager meetings and regular face-to-face reviews, which helped keep the program on schedule and deliver performance objectives while continuing to identify and pursue additional synergy opportunities. Remarkably, BP met all its major integration targets on or ahead of schedule, and the synergies delivered during the first year of combined operations exceeded expectations.

A cross-border merger also offers the opportunity to institute changes that might otherwise be difficult to implement. Spanish oil company Repsol saw its 1999 merger with YPF of Argentina as a mandate for dramatic change. The company’s goal was to transform its management and culture from an operation based in one country to a multi- national entity with the flexibility to adapt to different markets.

Repsol YPF designed and implemented a comprehensive new management model that resulted in a transformed organization with updated business processes. The upshot: a more strategically competitive, culturally unified, efficient and client-focused operation, which is also the largest private energy company in Latin America in terms of assets and among the 10 largest such companies in the world.

Finally, to stay ahead of the game, the most successful players invest in distilling and institutionalizing the lessons learned from the process. Cross-border acquisitions are like potato chips—you rarely want just one. By creating repeatable processes and identifying internal experts, sub- sequent acquisitions can be closed faster and integrated quicker and with a higher likelihood of success.

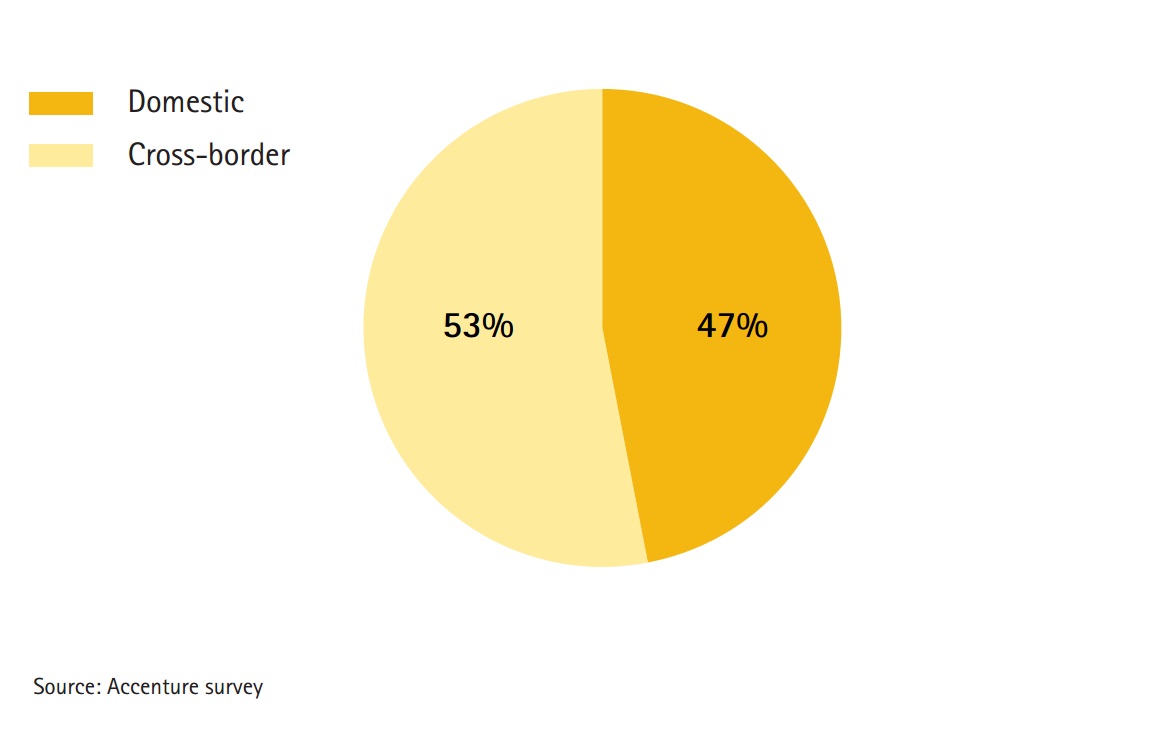

Looking abroad

A little more than half of the mergers or acquisitions recently completed by 508 companies surveyed by Accenture were cross-border deals.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter