Publications Leading Through Transition: Perspectives On The People Side Of M&A

- Publications

Leading Through Transition: Perspectives On The People Side Of M&A

- Bea

SHARE:

By Deloitte

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) present both opportunities and challenges for the executive team charged with leading the organization through these transactions. M&A activities drive significant change within your organization and can create complex situations, especially when it comes to managing employee transition. After all, getting it right with your organizations’ greatest asset — your people — is critical to Day One success and beyond.

This compendium is intended to provide company leaders with a deep dive into the human capital complexities you are likely to face during an M&A transaction. The articles explore many of the common people-related integration challenges and offer recommendations for how to approach these situations to meet your organization’s specific needs.

Section 1: Due Diligence

Learn as much as you can as quickly as you can in order to make the appropriate decisions.

The Top 10 Myths of Human Capital Due Diligence

By David Carney, Eileen Fernandes, John Fiore and Glen Lipkin

Due diligence is the thorough investigation an acquirer performs prior to purchasing a target company. Insightful and material due diligence prior to consummating the deal greatly increases the likelihood that the acquirer will achieve the expected strategic goals and synergies. It is important to learn as much as you can as quickly as you can, so the due diligence team can make the appropriate decision.

Human capital due diligence is an important piece of the overall due diligence process, yet for some reason it is too often underestimated or undervalued. Thorough human capital due diligence is much more than just benefits and compensation analysis. It is a critical component of an effective merger and acquisition (M&A). The fact is, personnel-related expenses are typically the largest selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expense items on the income statement of most companies — correctly identifying significant cost increases and hidden liabilities could account for millions of dollars in a transaction.

It may look like an imported sports car, but it runs like a lawnmower.

In a number of ways, the due diligence process is similar to buying a car. It is very tempting to look at a nice, bright, shiny car and say: “I will take that!” But remember — you do not want it just to look good. You will be spending a lot of time with the car, and it needs to run well. And for most individuals, a car is a significant investment. So before you buy, you need to check under the hood, pump the brakes, and kick the tires or you might end up still on foot! Let’s take a look at 10 of the biggest M&A — and carbuying — myths.

Myth #1: Human capital, tax, finance, accounting, legal — we all speak the same lingo

I can drive it, surely I can fix it

Human Resources (HR) due diligence is tightly linked to the due diligence efforts of tax, finance, and accounting. Just because everyone on the team is skilled at due diligence does not mean that they necessarily will understand each other’s findings. Each functional due diligence team needs to understand all the valuation assumptions, how its work will influence the Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA) pricing model, and how its work integrates into the larger puzzle. Traditional and extended human capital due diligence teams often find it easier to report their findings in their “native human capital tongue,” which may be a different language than what the rest of the team expects and understands. Mechanics who fix domestic vehicles are not always the most appropriate choice to fix imports! Because all due diligence findings are eventually quantitative and represented in certain broader financial metrics, the human capital due diligence teams need to be sure that various items, such as pension expense, errors and omissions (E&O), directors and officers liability insurance (D&O), incurred but not reported losses (IBNR), and per employee, per year cost (PEPY), are converted to financial metrics, such as EBITDA and pro forma statements. The often technical human capital due diligence also needs to be represented in the universally understood financial language.

Keys to achieving results:

• Understand on what basis the company is being valued.

• Work closely and communicate effectively with everyone on the team.

Myth #2: Human capital due diligence work is stressful and repetitive — it is not worth the effort

Finding the car of my dreams is not worth the effort, what I have now is fine

Mergers and acquisitions create highly visible opportunities for the acquirer, the target, and the professional services firms that support them. With high risk comes high reward: due diligence projects often entail long hours filled with operational details and a frustrating lack of information. However, those long and intense hours are often offset when a deal closes, and the newly established entity or merged company goes through a seamless transition, and successfully starts realizing the deal rationale.

Conducting human capital due diligence is a beneficial training ground for all parties involved, and the acquirer, the target, and the professional services firms benefit. Going through the due diligence process, all parties benefit from the knowledge exhange in working with highly skilled and knowledgeable project teammates and leaders of their specialty. Human capital due diligence provides clients the benefit of working with industry-leading professionals and benefit from their functional knowledge both deep and broad.

Keys to achieving results:

• Set the tone for your team on the deal. Is it a sprint or a marathon?

• Become a sponge — you’ll gain a wealth of knowledge working with accomplished individuals.

Myth #3: Benefits and compensation. What is the big deal? Why bother?

The engine looks nice and shiny; I’m sure the car runs great

It is critical to understand that personnel-related expenses are typically the largest expense item on the company’s income statement. Correctly identifying significant cost increases and hidden liabilities could account for millions of dollars in a transaction. Human capital financial due diligence evaluates several areas within HR and other related functions. Human capital due diligence specialists have broad and deep experience in a wide variety of areas — much more than an HR generalist. Legal liability is a technical area with many codes and acronyms, such as PBGC, 280G, 162(m), CIC, Section 75, etc. Due diligence teams need to look at legacy liabilities, such as pensions; post retirement medical, health care, and insurance costs; parachute payments; and deferred compensation plans — to name just a few.

Keys to achieving results:

• Don’t underestimate the risks inherent in the “benefits and compensation” line.

• Understanding the feasibility to transfer financial statement risks.

Myth #4: Diligence is diligence, regardless of whether it is for a strategic or financial buyer

Buying a car for myself is the same as buying one for my spouse

Professional services firms thrive on developing effective, innovative, and insightful methods and approaches that can be applied repeatedly to various clients. While leveraging leading practices and sticking with what has worked in the past usually works well, this “one-size-fits-all” approach may not always work in due diligence. M&A deals are divided according to the type of investor buying the company. “Financial” buyers are individuals or investment companies (for example, private equity funds) seeking acquisitions that provide favorable cash flow. “Strategic” (also referred to as “corporate”) buyers are companies seeking to acquire other companies to acquire operational economies, additional market share, technology, or some other synergy. Understanding the environment provides the due diligence team with the appropriate focus to uncover material findings. For example, while strategic deals may focus more on culture, leadership, and synergies, financial deals may focus solely on costs.

Keys to achieving results:

• Know and understand your buyer.

• Prepare for the end at the beginning.

Myth #5: A dollar equals a dollar

Cars are maintenance free, no need for me to budget money for repairs and upkeep

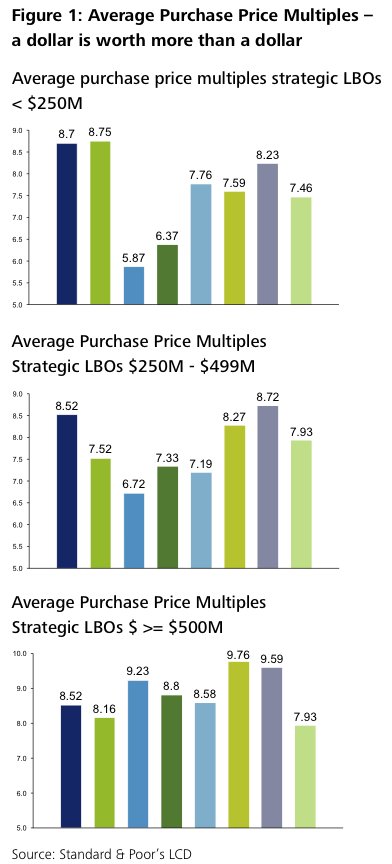

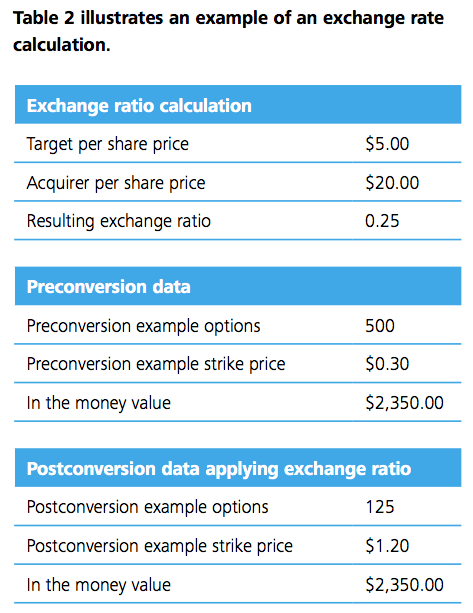

The path to pricing a company is lengthy and complicated. It requires hundreds of pages of financial modeling and a web of strategic and operational analyses. Boiled down to its simplest form, the price that the buyer and seller eventually agree upon is generally a multiple of EBITDA. Because this multiple is greater than one (see below), a dollar is worth more than a dollar because each uncovered dollar could affect the purchase price by $5-$10.

Keys to achieving results

• Understand the general multiples.

• Keep perspective.

Myth #6: Size does not matter

SUV or roadster – a car is “just” a car

Great market conditions and enormous amounts of available cheap debt have brought investing into a brave new world. Multibillion dollar strategic buyers and private equity investors alike have the leverage to make deals topping over $30B.1

At the same time, while the top end is increasing, there are smaller companies and literally hundreds of private equity funds making countless deals of $1B or less.2 Before focusing on what is material, you need to understand the considerations around the size of the deal. For example, a $100M payment due on change in control is crucially material as it could kill a $1B deal. However, in a multibillion- dollar deal, $100M could be pennies on share value.

Keys to achieving results

• Evaluate the environment and assumptions and have perspective.

• Don’t sweat the small stuff (unless the deal size requires it).

Myth #7: We’re HR benefits specialists — there’s no need to mix with the bean counters

I do not need to check with other family members before buying a car

In a simple world, everyone sits in an assigned cubicle and works within the scope of his or her own job. But in today’s virtual and highly interconnected world, global companies are interdependent — sharing resources, programs, and systems. It is integral to overall due diligence results for the human capital diligence team to work side by side with the accounting, tax, finance, and legal diligence teams. Financial and accounting teams will have data HR may not have access to, such as detailed trial balances and cash flow statements. There may be overlap with certain legal and tax issues; so it is important to complement and not duplicate. Working as one team is critical to identifying and managing interdependencies.

Keys to achieving results

• Work together to assemble all the pieces.

• Organize centrally and work as one team.

Myth #8: Online data rooms make life so much easier

Buying a car online takes just two “clicks”

There’s no question that advances in technology have dramatically changed the way we work. Software programs and electronic tools are designed to facilitate cooperation and increase efficiency and productivity. On M&A deals, data rooms are an integral part of the due diligence process. A traditional data room is literally an actual room — secure and continually monitored — where advisers visit to inspect and report on the various documents and data available. Often only one bidder at a time is allowed, and in large due diligence processes, teams have to be flown in across the world to remain available throughout the process. An alternative is a virtual data room — an online repository with limited users, controlled access, and restricted functionality for forwarding, copying, or printing. There are pros and cons to both kinds of data rooms, so do not automatically assume that online data rooms will make your life easier.

Online data rooms can control costs, save valuable travel time, and give the due diligence team members the ability to sleep in their own beds at night. However, being able to meet face-to-face with the target, or physically meeting with your team members in a war room, can create an environment that is more conducive to open communication and can lead to additional valuable insight. Therefore, while online data rooms may allow you to work 24×7, both options should be considered based on circumstances of the deal at hand.

Keys to achieving results

• Do not assume all online data rooms are the same.

• Be flexible.

Myth #9: I will get all the data I need

Car brochures tell me everything I need to make an informed buying decision

Due diligence often sounds easier than it is — the team goes in, asks for all the documents, reviews them, writes a report, and voila, DONE! In reality, it is rather amusing (or scary) that multibillion-dollar companies lack documentation ranging from an accurate count and roster of all employees to inventory of all benefits programs, to documented policies and business processes. Even if you do receive the desired documents, it will often be 10 minutes before your report

is due. To add to that, it is important to note that timing is everything. The typical conversion rate for document response in M&A years is 1 day = 1 week — kind of like dog years. Therefore, be ready to go with the flow and be alert 24×7 — treat every discussion with management as your one and only bite at the apple. You will quickly learn to live with incomplete data and use your own judgment to fill in the gaps. Just be sure to clearly document the holes and any assumptions you have made.

Keys to achieving results

• Establish a two-way dialogue.

• Work with the target team, not against it.

• Show the target you are serious about the process.

Myth #10: It won’t hurt if I just tell a few people what I am working on — it is so cool!

Telling the car dealer how much I am willing to pay doesn’t put me at a competitive disadvantage

There is no doubt that M&A projects are attractive and prestigious — high risk/high reward, high input/high output. It provides you with an opportunity to work in a high-stakes, highly visible environment involving top specialists in the field. It is natural to want to share the excitement with friends and family. However, that may be a very costly and detrimental mistake. In today’s business environment of extra scrutiny and attention to ethics, the person you try to impress could cost you big time. To control the integrity of the deal price and avoid irrational movements within the company and the market, M&A deals are highly confidential until publicly announced. As professionals, our commitment to integrity is our code and must be honored 100% of the time.

Here is a real-life example of what could happen otherwise. Early in March 2007, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission announced that it had frozen $5.3 million in profits from unusual patterns in trading of a large energy company’s options a few days before the February 26 announcement of its leveraged buyout. Regulatory organizations closely monitor activity globally, and irregular patterns on call options and stocks purchases are detected and prosecuted, as in this case. Do the “front-page test” before sharing your excitement about work — how would you react to reading about your actions on the front page of The New York Times?

Keys to achieving results

• Integrity

• Integrity

• Integrity

Conclusion

Although due diligence is routinely performed when acquiring or selling a company, it is often conducted too quickly or too narrowly, focusing primarily on how a company has historically performed financially. And while financial, legal, and environmental due diligence is critical to the effectiveness of any acquisition, it is not everything that needs to be considered. A multidisciplinary approach — one that includes human capital — is far more powerful and revealing.

The bottom-line: human capital due diligence is a critical results factor when it comes to M&A. Human capital due diligence can significantly increase the likelihood that a deal will meet its objectives.

Anatomy of Acquisitions

A guide to Human Resources Management contributions in the early phase of a buy-side transaction

Mergers, acquisitions, spin-ins, spin-outs, divestments, joint ventures, and strategic partnerships each represent business transactions outside a company’s normal course of business. A fundamental problem exists in every transaction for human resources (HR) practitioners on the frontline: they contribute too little to the transaction at the point in time where they would add the most value. The objective of this article is to put transaction activities and HR management accountability into a practical context so that HR practitioners can more effectively engage, accept accountability, and contribute to the transaction process from beginning to end.

There are seven flags outlined here that indicate where the effectiveness of the HR contribution is compromised and five points for HR organizations to consider when building competency in nontraditional business transactions. This is not intended to be a detailed review of the HR process, but rather an overview of a portion of the transaction process rarely viewed by HR practitioners. There are many nuances and specifics beyond this discussion that should be explored by any HR practitioner beginning a project.

1. & 2. A transaction project presents unique HR challenges to both the buying and selling companies. If an HR team is unaware of a strategic gap in the company, then consider this red flag number one. If the HR team does not know how the people strategy incorporates nontraditional business requirements, consider this red flag number two.

HR Accountability

Confirm your people strategy accommodates or recognizes the potential for nontraditional business relationships. Acquisitions, joint ventures, and strategic partnerships will demand similar competencies to complete the transaction effectively, but the people strategy will differ significantly.

3. Once a business team has settled on a business transaction as the solution to the problem, searching for a suitable target ensues. If the project is a surprise to the HR team, this would be red flag number three.

HR Accountability

Know the labor market in which your target competes for talent. Alert the HR team, shared services teams, and other HR stakeholders with the potential of a significant project that will test their individual capabilities, as well as the HR organization’s standard operating practices.

4. Target company identification is usually based on technical or market factors that close the strategic gap in the existing company’s product or market strategy. A preliminary valuation and one-sided assessment of the target begins, and will conclude, when the company is comfortable, economic value is established for the target, and certain terms of an agreement are accounted for (i.e., the negotiation strategy is understood). If the HR team does not have an educated guess at all human capital value drivers with the target before taking a recommendation to the corporate board, consider this to be red flag number four.

HR Accountability

Know your target, its leaders, and their interests and motivations. Know what it will take to retain intellectual capital, restructure the company, integrate infrastructure, and quickly establish new employment relationships.

At this point, HR infrastructure is not on the radar. Stay out of the details and work to the business case. Do not wait for a formal due diligence period. Later this article outlines where all of the groundwork for key decisions that determine 80 percent of the transaction’s value will be determined, before you reach formal due diligence and negotiation.

5. The company takes its recommendations to the proper corporate body to get approval to move ahead with economic issues, terms and conditions, and other unique considerations.

HR Accountability

Economics will include such factors as the value of the transaction to employees, the value of any retention to be applied to employees, the rationale for such a value, executive compensation issues, employment relationships, restructuring, impacts to the existing HR infrastructure, etc. If the approving corporate body does not have visibility to these costs, consider this red flag number five.

6. The company’s recommendations are approved. The company may now approach the target and begin to implement its negotiation strategy. An outcome of early negotiations is a Letter of Intent or a similar document and an agreement that the two parties will negotiate exclusively for a specific period of time. If the HR team is still out of the loop at this point in time, consider this red flag number six.

HR Accountability

As noted earlier, 80 percent of the groundwork for key decisions is laid before a formal due diligence period. A Letter of Intent may propose the disposition of things like employee stock options, employee benefits, treatment of executives, restructuring, employment agreements, and the disposition of any unique items, such as change in control agreements, promissory notes, or acceleration of equity. There may be some administrative items included here, such as protections under IRS Section 280G(a) and some covenants regarding confidentiality and maintenance of standard operations in the time period between negotiations and due diligence.

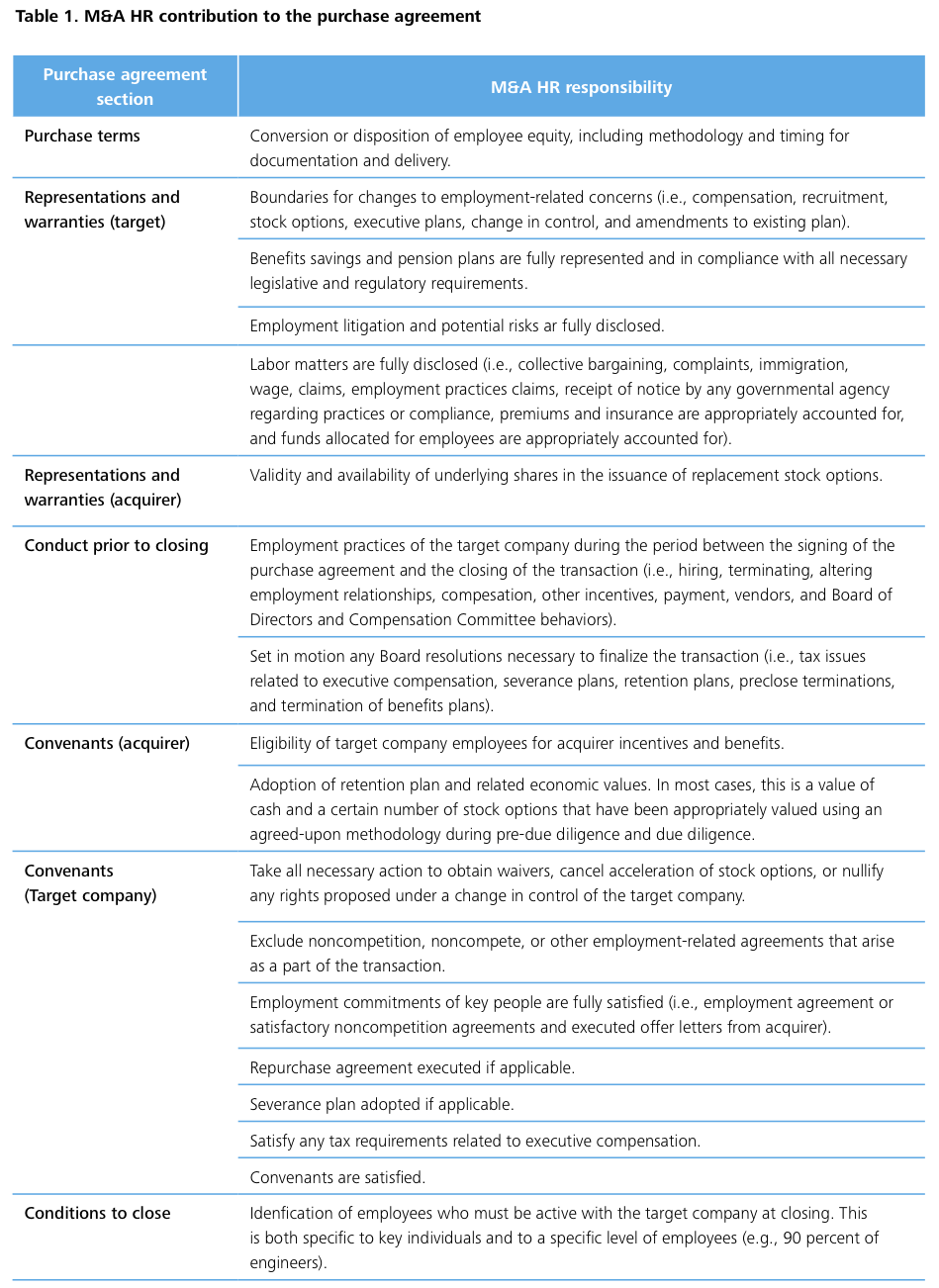

7. Upon agreement of the terms, both parties will agree to a formal due diligence process. This will be completed in the period of exclusivity. Concurrent with due diligence will be a variety of critical negotiations.

HR Accountability

As a contributor to formal due diligence, HR validates all of the preliminary work already underway in the project analysis, identifies potential risk to the business plan, identifies liabilities, formalizes an integration framework for HR infrastructure, engages communication efforts, and provides organizational stability for the company.

As a contributor to negotiations, HR will define the employment characteristics for the new team and its executives allocate and structure retention funds, conduct a pro forma restructuring of the company, set terms in the purchase agreement around the disposition of employee equity, treatment of employees postclosing, representation and warranties by the target, covenants to guide operations between signing the deal and closing the deal, and other unique characteristics that arise as a part of the deal.

If HR is evaluating only potential risks and liabilities in the infrastructure of HR services, consider this red flag number seven.

As due diligence concludes and negotiations are completed, the project will be publicly announced, but will not be complete until several weeks or months later when the necessary administrative and legal obstacles are closed and the negotiated value of the deal is transferred from the acquirer to the target.

Know your target, its leaders, and their interests and motivations.

Key take aways

1. Loose documentation of processes

Focus on what is important and how you get there. Do this with a Corporate Development person or your business unit management team. Find experienced HR teams to benchmark against. There are different models for different types of transactions and corporate styles.

2. Develop acquisition competency throughout the HR organization

If you have a shared services platform, find a resource that you can draw on as needed and be confident that you understand each other’s requirements in terms of flexibility in the mainstream systems.

3. Build an HR acquisition toolbox

Build a template for your positions in preliminary evaluations, negotiations, structure of contracts, integration plans, communications, restructuring, executive arrangements, retention, etc.

4. Facilitate and lead integration processes

Act as a single point of accountability for HR integration. Line HR must take ownership and accountability for the results of the integration, solve problems, handle the unique deals and surprises, and lead change. The tendency is to abdicate functional integration activities to other people and spread the accountability too far. This will most likely result in a loss of credibility for the Line HR person.

5. Resource projects properly

Transactions are the most intense work most people will ever do. Find people who have tolerance, judgment, open minds, an ability to solve problems, and who are generally fun and interesting. Once you find them, align them to you and reward and recognize them beyond their expectations. You will almost certainly work them harder than you anticipate.

Where’s HR?

Positioning Human Resources as a strategic due diligence partner

By Glen Lipkin, Nick Franklin and Lisa Scheiring

The days leading up to mergers and acquisition (M&A) deals are intense. The due diligence team is focused on scrutinizing financials, negotiating terms, and plotting strategies. It is tempting to reduce one of the biggest risk areas — human resources (HR) — into a number-crunching exercise focused on identifying potential financial risks and synergy opportunities, such as maximizing headcount reductions to generate compensation and benefit savings.

But the financial risks related to an organization’s people are the tip of the iceberg. While more difficult to quantify, factoring in people-related risks and providing a successful approach is critical to succeed in these areas:

• Structural risks: Organization design and selection must be pinned down to prepare for a successful Day One and beyond. This includes planning a phased approached to headcount reductions so that business as usual is not disrupted by the transition.

• Talent risks: Talent retention strategies and costs must be factored into the plan. People with critical knowledge and skills must be identified and strategies developed for keeping them onboard. Otherwise, you may lose key people just when you need them most.

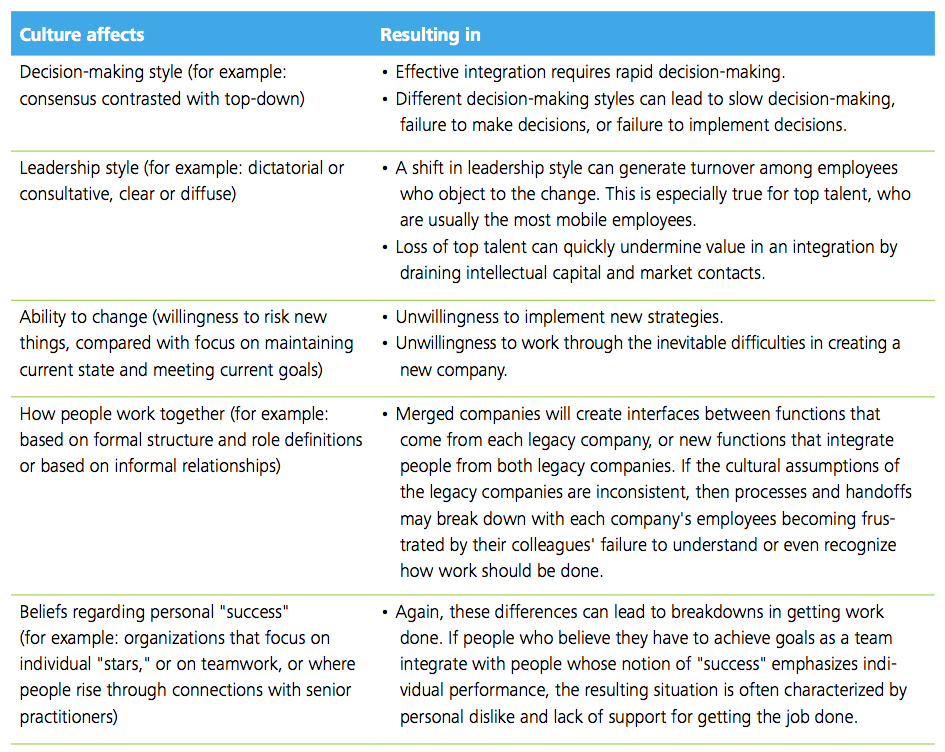

• Cultural risks: When two companies merge, cultural conflicts are inevitable, which may undermine the best-laid integration plans. It’s important to identify cultural differences, such as leadership styles, decision-making processes, receptiveness to change, work-styles, personal interactions, and believes around personal success. When a preliminary cultural analysis is conducted before signing, the due diligence team can better pinpoint possible hurdles that will hinder synergy capture and a smooth transition.

As a HR leader, you understand that oversimplifying people-related risks can lead to inaccurate integration planning scenarios, poor synergy predictions, unexpected costs, and loss of critical talent. So how do you become a strategic M&A partner who is engaged early in the deal process? And how do you build a respected HR M&A team that will help your organization capture people-related value in this deal — and subsequent ones? The following four-step approach should be considered in your efforts to get into the game.

Oversimplifying people-related risks can lead to inaccurate integration planning scenarios, poor synergy predictions, unexpected costs, and loss of critical talent.

Step One: Partner with the corporate development team

Typically, your company’s corporate development team drives M&A activity by developing the overarching strategy and identifying potential acquisition targets. HR should build a partnership with corporate development so that you will be engaged with them during target screening — or even strategy development. By understanding the deal team’s M&A objectives, you can provide insight into potential people-related challenges that could affect their decisions. For example, your company’s strategic direction may require adding a new business to the organization’s portfolio, growing a current line of business vertically or horizontally, or perhaps expanding into new global markets. Each scenario has a different impact on the people needs of the organization.

With this strategic perspective, your HR team can better support the due diligence team by helping identify information that must be collected from targeted companies to project people-related costs, integration issues, and synergies. Understanding the strategy behind the deal will also provide HR with a foundation for developing an organizational structure for a combined company that will be consistent with the strategic vision.

Step Two: Rightsize your HR M&A team

Whether your company is dabbling in M&A or has identified acquisitions as a primary growth strategy, you will need a capable and efficient HR M&A team. But this does not happen overnight; it requires support, training, and time to develop M&A knowledge and experience.

The frequency and complexity of the M&A transactions that the team is expected to handle will dictate the appropriate number of team members and the capabilities and tools they will need to be successful. There is a broad spectrum of possible team models that you can adopt. For example, if your company’s strategy is to execute a one-time deal, you may choose to use existing HR staff members on an ad hoc basis. On the other hand, if your company’s strategy involves complex, ongoing M&A activity, you may develop a dedicated staff of M&A HR professionals.

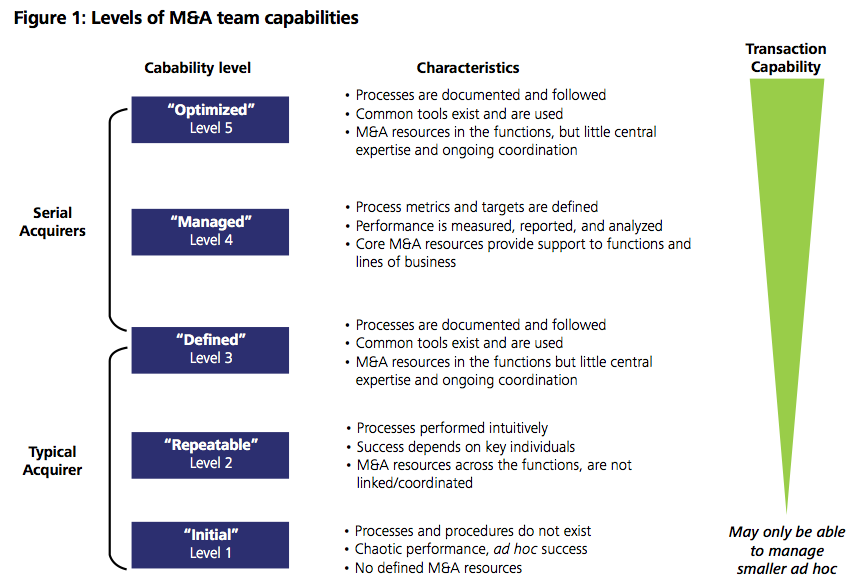

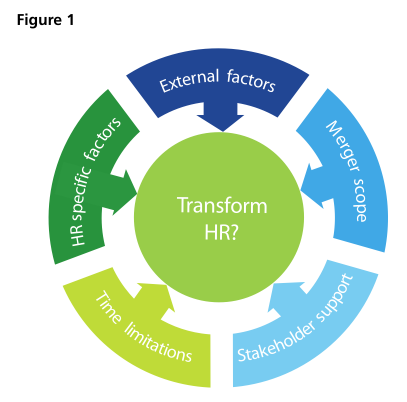

Of course, there are many team variations between these two extremes. Figure 1 illustrates the range of possible M&A team capabilities. Inexperienced teams will probably perform at Level 1 or 2, with limited capabilities that could result in inconsistent performance. As the team expands and gains M&A expertise, they should move up the scale in effectiveness and ability to handle more complex transactions. A team’s progress can be accelerated by providing outside support with M&A experience, knowledge, skills, tools, and training.

Step Three: Find high-potential team members and develop them

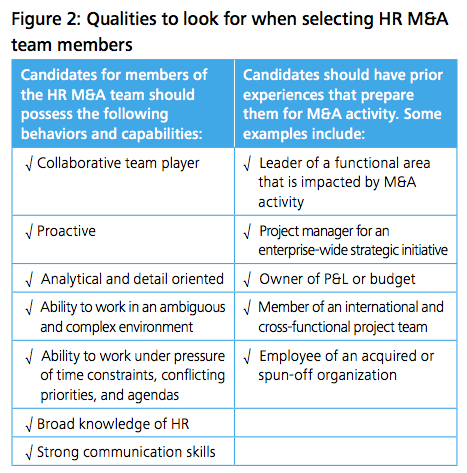

When selecting individuals for the HR M&A team, it is important to choose people who will thrive in a loosely structured, fast-paced environment. They must be able to work effectively with team members representing other functional areas who are often analytical and financial oriented. Box 2 outlines the qualities and experiences you should look for in team members.

If no strong candidates are readily available within your organization, there are several ways to develop internal M&A knowledge and skills:

• Use external professionals to jump-start the organization’s knowledge base: Many companies wait for the first transaction to surface and use external support, such as M&A HR consultants, project managers, and due diligence assistance, to help guide the integration and simultaneously help them in their efforts to build in-house capabilities. One benefit of this approach is that internal M&A team members gain hands-on training and experience during the integration planning and execution process that can be applied in future transactions. Plus, they gain access to the external professional’s knowledge, tools, and processes. Of course, there is a cost associated with hiring external professionals.

• Hire experienced people: Another option is to recruit experienced people who can mentor functional teams and share their knowledge and experience with others in the organization. The benefit is that a new hire with M&A expertise can train and guide other team members. However, qualified candidates may be hard to find, and unless there is a constant stream of M&A activity, the ongoing expense of an additional employee may be difficult to justify.

• Build internal capabilities over time: Relying on internal staff members who learn by trial and error allows individuals to build knowledge and experience over the course of several transactions. Leadership must be willing to accept that the team’s initial performance may be inefficient and ineffective, increasing the overall transaction risk; however, the incremental cost of using internal staff is relatively low, and the team’s performance will probably improve as they gain experience.

Step Four: Standardize the due diligence process. Tools, tools, and more tools!

A structured approach to the due diligence process can help the HR M&A team to function at a high level. If this transaction is likely to be the first of several, creating standardized processes can enable them to thoroughly and consistently evaluate targets. Examples of ways to make the due diligence process more efficient are:

• Document current processes. Compile and document your organization’s compensation practices, benefits systems, HR systems, and HR policies for easy reference. Have readily available detailed information about your organization’s operating model, payroll, and HR technology. By having a clear picture of current operations, it will be easier to evaluate the cost to migrate the target organization’s processes and systems.

• Create tools to improve efficiency. Customized tools and templates can help expedite information gathering during the due diligence process. Some useful tools are:

–Standard data requests for collecting information from target organizations

– Detailed checklists of all due diligence tasks to be performed

–Templates for side-by-side comparison of compensation and benefit plans

–Outline a standard due diligence report that will be completed following a thorough review of a target’s people-related risks, including quantitative data to be incorporated into the deal team’s financial analysis and qualitative information to provide executive leadership with an overview of the target’s top HR risks

Conclusion: Arrive early and come prepared

You and your HR team can provide a valuable perspective on the people-related risks that may otherwise be overlooked. By partnering with the deal team early in the due diligence process and developing an effective HR M&A team, you can help identify and mitigate financial, as well as structural, talent, and cultural risks inherent in the transaction. Armed with complete information, your organization will be in a stronger position to negotiate a price that more accurately reflects the costs and synergies associated with the deal.

Section 2: Integration Management

Anticipate the challenges of integrating two disparate sets of people, processes, and systems.

Taking the lead during a merger

How leaders choose to communicate during a merger is key to realizing the value of the deal

By Eileen Fernandes, Kevin Knowles and Cydney Roach

In the current climate of merger mania, the reality is that the majority of mergers will not live up to expectations and many will fail altogether. Most often this failure is not attributable to the structure of the deal, but to cultural conflict and poor communication. The key, is strong leadership communication from Day One.

How leadership chooses to manage and communicate the people component of merger and acquisitions (M&A) change is key to maximizing the value of the deal. Employees are, after all, those who will implement the changes to realize the merger vision. As top industry surveys have proven, of all the human capital issues involved, communication ranks as the top critical driver of merger results.

Why leaders fail to prioritize

So if communicating the vision and strategic rationale of the deal to employees is such an imperative in capturing merger value, why don’t leaders give it a higher priority in their merger responsibilities?

• Unlike many other merger related leaders hip activities, communicating with employees is not a legal requirement.

• When leaders hip time is being allocated during a merger, communicating regulatory compliance and presenting the deal to the financial community and all external stakeholders takes highest priority.

• At the best of times, leaders can be reluctant communicators. Given the intense time pressures that prevail during mergers, they are quick to find reasons to allow internal communication responsibilities to slide.

• Executives can be even less inclined to communicate with employees when they do not have answers to many of the typical questions employees have about their future, or when they must deliver difficult messages related to workforce reduction, a common reality of mergers. Of course, that is precisely when leaders should not be silent.

Better leadership visibility

Here are some tips on how to facilitate leadership visibility in communicating and driving merger integration goals:

• Explain the value they can unleash in helping employees live the change that will achieve these goals.

• Win confidence from leaders by presenting metrics that demonstrate the importance of communication with data derived from focus groups or change-readiness surveys.

• Most of the leaders hip on the core integration team comes from finance or operations. If you can provide percentages and charts, they are going to feel better about what you are purporting than if you approach them with a broad-based narrative for communicating.

• Explain you will need their buy-into push the kind of messages that are truly strategic, and that managers will then cascade those messages, adding more granular detail and tactical execution instructions to augment them.

Finally, offer leaders the following list of guiding principles when they formulate their merger communication strategy.

• Define a core message set—including strategic rationale for the deal, a vision of the new company, and key supporting facts — as early as possible.

• Stick to core messages, presenting one aligned identity to all stakeholders, internal and external.

• Be highly visible and especially communicative from the moment the deal is announced.

• Explain the line of sight between merger goals and what employees can do to help.

• Manage employee expectations and establish credibility with open, honest communication; painting too rosy a picture of the integration process will create more obstacles than achieve ends.

• Face difficult issues, such as workforce reduction squarely and candidly.

• Do not avoid communicating if you don’t have all the answers.

• Establish or reinforce two-way communication and feedback mechanisms; during this intense period of change, you’ll need the input to measure how well the integration is being implemented and how thoroughly the merger vision is being accepted.

• Create a positive sense of urgency to drive employees towards integration goals.

• Identify quick wins that will prove to employees that the integration strategy is working. Communicate and celebrate when those quick wins are realized and recognize those who helped achieve them.

Ultimately, leaders need to be reminded that communication has the power to drive the realization of integration goals.

Stacking the deck

By Carolyn Vavrek, Jessica Fleming Kosmowski, Alejandro Danylyszyn and Anna Kwan

A large number of mergers and acquisitions (M&As) often fail to achieve the financial or operational targets the deal architects expected before closing the deal. Even more starting, fewer than one in ten transactions are viewed as “successful” by executives and insiders in the new organizations.

Why do so many transactions fail to capture the expected value? And why is success so elusive?

Some deals fail simply because they never should have been done in the first place. But a much larger number fail because of poor integration planning, and execution, or because the company did not properly anticipate the challenges of integrating two disparate sets of people, processes, and systems. In some cases, failure might be inevitable. But in most cases, we believe the biggest obstacles can be tackled through an improved approach to merger integration.

Intelligent integration

Merger integration is a complex challenge, and there are no magic formulas for achieving your desired results. Every deal is different and dynamically unfolds in a rapidly changing business environment. However, our experience suggests that companies can greatly improve their chances for a positive outcome by putting more emphasis on integration planning and operational analysis early in the deal life cycle. This new approach — what we call “Intelligent Integration” — consists of three major elements:

• Accelerated planning – Committing to a more comprehensive operational analysis and integration planning during the due diligence phase can enable the deal architects to anticipate, identify, and mitigate people, process, and technology risks. This increased discipline can also prevent bad deals from being done — or at least reduce expectations for mediocre deals.

• Value blitz – An intense and focused effort at the start of integration planning can help leaders identify key deal value drivers and set priorities for the overall integration.

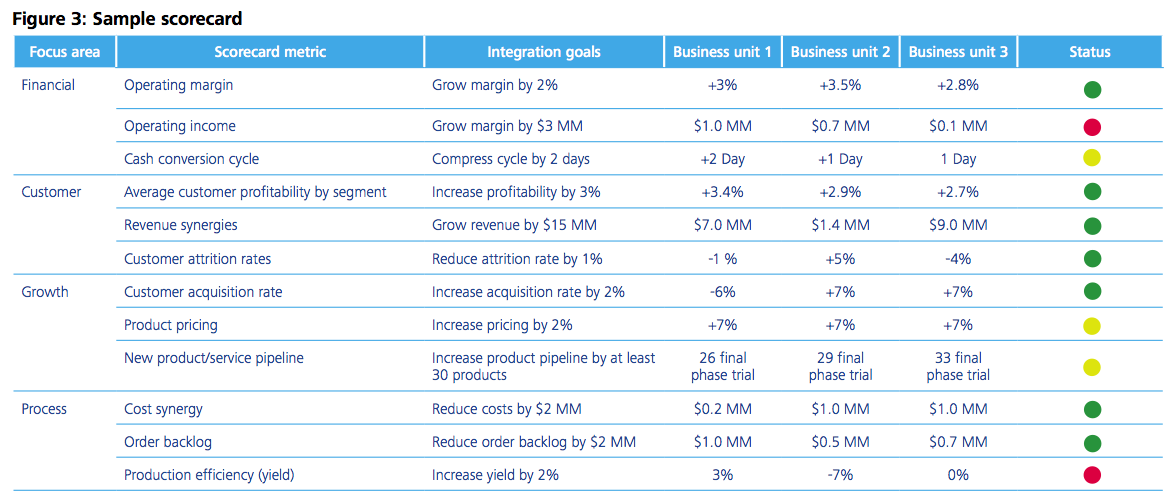

• M&A scorecard – A clear and balanced set of performance measures can highlight what integration teams should focus on, measure, analyze, and report to stakeholders. An effective scorecard can help define success, monitor progress, and keep the integration on track.

In theory, each of these elements can be implemented individually — but the combination can produce powerful results, enabling a company to dramatically increase its chances for success at every stage of the merger life cycle.

Increase the chances of achieving your desired results from a merger or acquisition by improving how you plan and execute integration activities.

Benefits of intelligent integration

For most companies, Intelligent Integration represents a significant shift from current practices. This approach can increase the chances for an effective merger by helping the company to:

• Identify potential deal breakers while there is still time to get out of the deal

• Accelerate the resolution of cultural, operational, or systems issues

• Focus integration effort and investments where they can drive the most value

• Develop objective measures to guide and measure progress and performance

• Accelerate synergy capture

Accelerated planning

During the early stages of most mergers, the main focus is on assessing the financial viability of the deal. The integration effort does not really kick into gear until the transaction is about to close or shortly thereafter. In particular, very little effort usually goes into integration planning during the due diligence phase, or even after the letter of intent is issued.

The integration effort intensifies as the close date approaches, and reaches its peak shortly thereafter. Over time, the required level of effort and investment gradually decrease. However, it is not uncommon for the integration to drag on for many months or even years after close. There are a number of problems with this traditional approach.

• Major challenges and risks with the deal may not be discovered until very late because of insufficient operational analysis and integration planning during the due diligence phase. Sometimes the leaders who can spot the big operational risks are not even in the know until well after announcement.

• Critical knowledge and activities often get lost in the hand-off from the deal team to the integration team, increasing the cost and risk of integration. As the pace of deals quickens, this risk can increase exponentially.

Companies can more effectively mitigate these challenges by getting an earlier start on operational analysis and integration planning.

This accelerated approach focuses more operational analysis and integration planning effort on the target screening and due diligence phases. By the time the letter of intent is issued, the company should already have a deep understanding of the operational challenges, cultural and organizational differences, and systems redundancies it will need to overcome.

Accelerated planning offers a number of specific benefit opportunities:

• Reduces hand-off risk. Because detailed integration planning and pre-close preparation are conducted in parallel with detailed due diligence and final negotiations, the integration team has direct experience with the deal and is less reliant on the deal team for key knowledge.

• Improves deal price. An improved understanding of the operational and integration challenges can help the deal team value the deal more effectively and negotiate a better price.

• More realistic targets. A deeper understanding of the postmerger challenges enables the company to set reasonable synergy targets and market expectations.

• Avoid bad deals. Accelerated operational analysis and integration planning can help the company identify deal-breakers-operational issues and integration challenges that make a merger inadvisable. If the deal does not go forward, the cost of this accelerated analysis may appear to have been wasted — but compared to the cost of executing a bad deal, it is likely a drop in the bucket.

• Reduce overall cost and effort. An accelerated approach shifts much of the analysis and planning to earlier stages of the deal, spreading integration costs more evenly across the merger life cycle. In our experience, in most cases, this increase in upfront costs is more than offset by reduced cost and effort in the integration phase.

Value blitz

No matter when integration planning occurs, the first steps are the most critical. Unfortunately, many integration planning efforts start out in chaos, with leaders bouncing from one fire drill to the next without a clear set of priorities.

A more strategic approach is to have a small team of key decision makers step back and quickly assess which integration activities are likely to create the most value – and then steer the overall effort to focus more time and effort in those key areas.

We have found that in most cases, the key focus areas that emerge from this “value blitz” will revolve around “value events” — business transactions or interactions with the potential to drive unusually high business value and help the company get a competitive edge in the marketplace. These events differ from one business to the next, and are inextricably linked to the company’s business and M&A strategies.

For example, a company that is merging to expand its market share should focus on integration activities that relate to customers, such as customer service and contract renewals. In contrast, a company that is basing its merger strategy on innovation should focus greater attention on the people, processes, and technology that drive R&D and new product launches. This focus on value events helps drive rapid performance improvement on Day One and beyond.

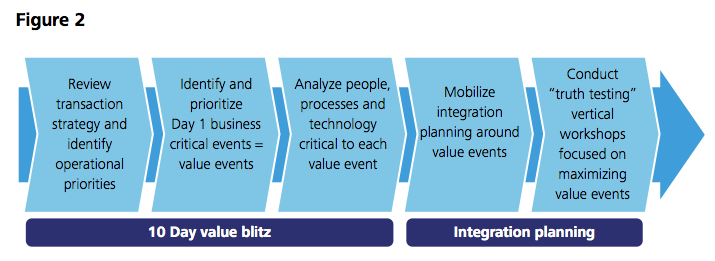

A value blitz is usually conducted during the first 10 days of integration planning. Figure 2 shows the typical steps in the process.

The team for a value blitz should be small, in most cases five people at most. It should include leaders from the business as well as key enabling functions, such as finance, operations, human resources, and IT. It is ideal if each member of the team has prior integration experience and a grounding in operational execution. It also helps if they can stay involved through all phases of the integration life cycle — from value blitz to planning to execution — in order to maintain continuity and direction.

If possible, the value blitz should occur prior to the deal signing and include at least one member from the due diligence team. This can help the deal team make a clear and efficient hand-off.

Useful tools for the blitz include critical event checklists and templates, process and system integration accelerators, and synergy capture estimators. With these in hand, the team can be productive from the outset.

Detailed integration planning, centered around the value events, can occur once the value blitz is complete. Integration teams should make regular reports of progress on the value events to help keep the company’s top integration priorities in sharp focus. These value events would be key metrics reported in the M&A Scorecard.

A value blitz is a good example of the need to “go slow to go fast.” It takes patience and discipline to make it happen, but the small investment of time and effort is likely to pay for itself many times over during the course of the integration.

M&A scorecard

Merger integration is complex and time-consuming, and many companies struggle to measure and deliver the merger value their investors are expecting. An M&A scorecard can help to keep things on track by focusing attention on key performance areas, and by making it easy to monitor progress and results.

A comprehensive M&A scorecard should provide a clear and balanced view of what integration teams should focus on, measure, analyze, and report. It can also be helpful in defining success.

• Implementing an M&A scorecard involves four steps:

• Translating the merger vision and strategic rationale into operational goals

• Identifying and agreeing on key M&A metrics

• Linking the M&A metrics to performance targets for key individuals

• Monitoring integration activities and adjusting the plan and strategy as needed

The scorecard should include a balanced mix of metrics, not just financial ones. The focus areas in the scorecard should be driven by the business strategy, merger strategy and value events, but other components to consider include:

• Objectives and goals for the integration

• Integration and/or divestiture initiatives

• Key metrics (e.g., customer experience, customer retention, customer profitability, revenue)

• Analysis and real-time feedback to drive continuous improvement, innovation, and growth

An M&A scorecard should be used to keep the deal “honest” and make it easier for leaders to stay focused on delivering the value all parties want from the transaction.

It should also help measure integration effectiveness across different deals by establishing a core set of standard metrics that can be used from one transaction to the next, which boards could then use to measure C-Suite performance.

Stacking the deck

Although companies often have legitimate reasons for delaying their integration planning activities, our experience suggests that sooner is almost always better. Intelligent Integration (1) places more emphasis on operational analysis and integration planning early in the deal, (2) focuses on business activities that drive the greatest value, and (3) provides a scorecard to define and monitor success. This three-pronged approach can significantly improve a company’s chances for success in every phase of the merger life cycle.

Merger integration is fraught with risks and challenges, and there are no guarantees. However, an effective approach to integration planning and execution can help stack the deck in your favor in every phase of the merger life cycle.

Thriving in a pressure cooker

Leading your merger integration team through the toughest project of their careers

By Kevin Knowles and Laurel Vickers

After weeks of heads-down concentration, followed by the adrenaline rush of the chase, you are poised to sign a merger agreement that will position your organization for future growth. The team you have in place to manage the deal has crafted the acquisition strategy, screened targets, and completed due diligence. Up to this point, it has just been you and a handful of other company leaders involved. Soon you will expand the ranks to prepare for the daunting challenge of integrating two organizations.

What happens when you pull your most valuable people from their day jobs and dedicate them to a project of this magnitude? How will they cope with the pressure? How can you help?

Integrating two organizations is a huge project — possibly the highest risk and most visible project your company has tackled. It is easy to become fixated on financial reports and Gantt charts plotting the multitude of tasks required to combine operations and squeeze value from diverse systems, processes, and employees.

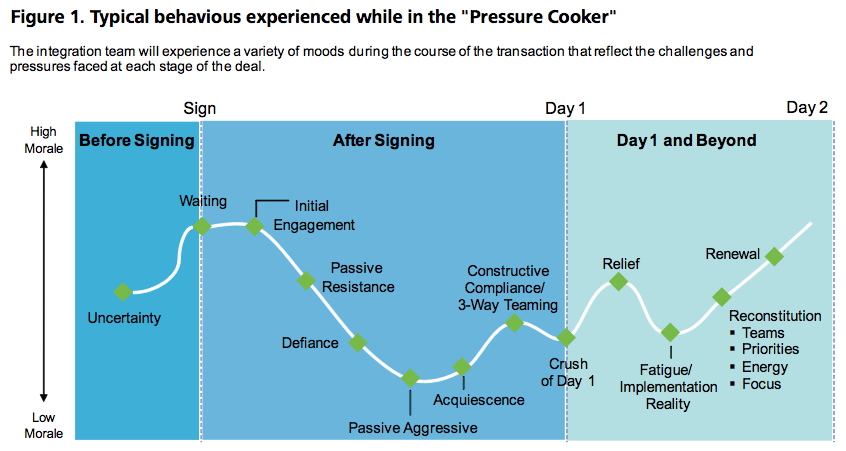

But it is equally important to attend to the human side of the integration project. The transaction can be undermined by disruptive behaviors and emotions of the people you are counting on to plan and execute the integration. Based on our experience of working with hundreds of integration teams, we have found that there is a natural emotional rhythm that accompanies the life cycle of the project, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Fortunately, there are actions that can help mitigate the low points and reinforce the high points. This article outlines what leadership should consider doing to guide and support the people who make up the integration team, to enable them to plan and execute a smooth transition while capturing the value promised to your stakeholders.

Before signing: Preparing to cook

Probably at this point, only you and a few others know for sure that a deal is in the works. While you may be tempted to wait until you have a signed agreement before beginning integration planning, now is the time to jumpstart the process by establishing the integration team structure and roles.

Be aware of the mood: You can be almost certain that functional leaders are aware of industry or office rumors about a possible acquisition. Speculation creates uncertainty, and the people you are counting on to lead the integration may decide to take a recruiter call and consider opportunities outside the company. Of course you must comply with confidentiality restrictions, but you can reduce their fears — and set the stage for a successful transaction — by engaging key functional leaders in the integration planning process early on.

Mind shift required: A successful integration requires leaders to embrace a new vision for their organization, rather than focus on their personal and functional area needs. They must adopt a collaborative project mindset that will allow them to champion change and participate in planning and executing complex interdependent activities within a tight timeframe. There are some key actions you can consider taking in your efforts to achieve the mind shift:

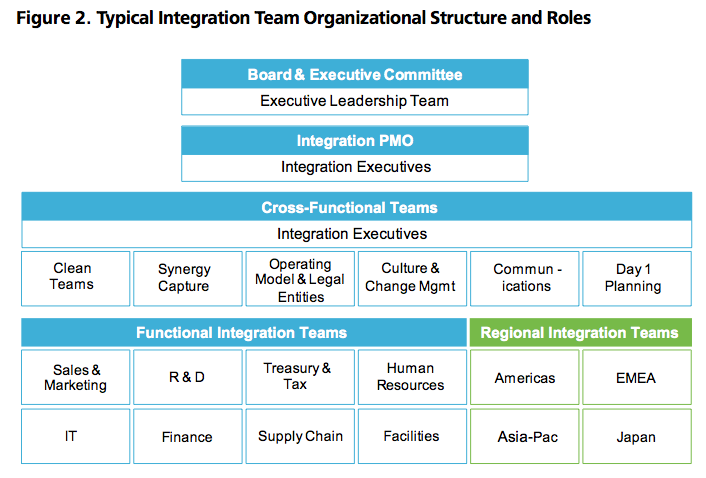

• Establish the integration team structure. At this early stage before signing, focus on establishing the roles and responsibilities of the top tiers of the core integration team. Create a flexible team structure that allows roles to be added as needed or as confidentiality restrictions loosen. Figure 2 shows a typical integration team organizational structure and roles.

• Identify core integration team members early. Once roles are defined, identify the best people to fill them. The size of the core team will vary depending on the size of the organizations and complexity of the integration. For typical midmarket transactions, a good rule of thumb is 10-20 functional leaders, representing a wide range of perspectives who possess the skills and desire to lead during transformational change. The integration team should be forward-thinkers capable of garnering support from different functions within the organization and bringing people together to achieve the end-state vision.

• Reach agreement on the team’s guiding principles. Hold an initial meeting with the core team members and share executive leadership’s strategic vision and goals behind the transaction. Direct them to get a head start on integration planning by formulating the team’s guiding principles and the decision-making governance model they will follow. This will allow the team to get prepared and help them be productive once the agreement is signed.

After signing: Reaching full boil

With the transaction agreement signed, the integration team can expand its ranks and begin to outline the work that must be completed to strive for an issue-free Day One. They can also begin preliminary planning for attaining the organization’s end state, when integration is complete and the transaction’s strategic goals and synergy targets are achieved.

The IMO should drive a rapid-fire cadence, which requires the team to plan and execute integration activities under tight deadlines. Simultaneously, team members must anticipate and mitigate integration issues and risks that arise, often with limited information. As Day One approaches, the workload will continue to intensify, requiring the team to expand to include middle managers and others needed to accomplish the many tasks required to make Day One a success.

Show of trust can result in a morale boost for the functional area, as well as help identify and groom future leaders for the organization.

Be aware of the mood: At the time that the agreement is signed, the core integration team has been patiently waiting to begin the work of integration; they are usually cooperative and willing to do whatever it takes to make the transaction a success.

As the team begins to grasp the magnitude of the integration work ahead — on top of the pressure of maintaining their day jobs — some members may passively resist conforming to the project’s highly disciplined processes and strict deadlines. A few may even become defiant or passive aggressive. But as Day One approaches, successful integration teams realize that the organization’s future depends on their performance. A shift occurs as the team pulls together and disruptive individuals acquiesce and rejoin the team or separate, if necessary. Together, the newly cohesive and motivated team can focus on accomplishing all the tasks required in the pre-Day One rush.

Mind shift required: An integration project takes most people far beyond their comfort zone. In the past, most team members probably relied on their individual knowledge and skills to drive their success; a project of this scope requires them to depend on each other to achieve success. Likewise, they may be accustomed to having plenty of time and resources to dedicate to thoroughly investigating alternatives before making a decision. During the fast pace of integration, they will be required to make decisions on the fly without complete information, usually with no looking back. Team members must develop tolerance, and eventually respect, for the structure and discipline required by the IMO so that all work is complete and interdependencies addressed for an issue-free Day One. There are some key actions you can consider taking in your efforts to achieve the mind shift:

• Set realistic expectations during a team launch meeting. The meeting that launches the integration team sets the tone and expectations for the rest of the project. The integration leader should:

– Acknowledge that team members were chosen because of their value to their organization.

– Share executive management’s vision for the future organization and the strategic goals for the transaction.

– Clearly describe the work demands and expectations for accomplishing Day One and end-state goals so team members are not surprised by the heavy workload and grueling pace.

– Set the team’s expectations by explaining that their integration responsibilities may extend well beyond Day One.

• Provide support for their “dayjobs.“ During the weeks or months leading up to Day One, an integration project becomes a full-time job on its own. When team members are concerned that their normal responsibilities are being neglected, their frustration and resentment will likely increase, and could affect the success of the project. Leadership is responsible for setting expectations and structure around resource planning and budget allocations for the integration. Using these guidelines, the integration team should develop a detailed resource model that is aligned with the integration objectives, while maintaining business as usual. Options the team should consider include offering opportunities to lower-level managers to assume larger roles within their functional areas by taking over some of the integration team members’ day-to-day responsibilities. This show of trust can result in a morale boost for the functional area, as well as help identify and groom future leaders for the organization. Another consideration is to hire temporary or contract employees at the lower levels so that people are not stretched too thin.

• Keep a finger on the team’s pulse. Leadership’s role in an integration project is complex. It is important to provide the team with the resources, timelines, schedules, and templates so they are effective and efficient. But, there is an artful side to integration leadership as well. An astute integration leader will know when it is time to push the team hard, and when it’s best to back off and encourage people to catch their breath. Strong interpersonal skills are required to know how to pull the team up when morale dips or address disruptive behavior. There are no firm answers; the integration leader must manage the team’s work pace so it maintains the momentum needed to cross the finish line on Day One.

Day One and beyond: Releasing the pressure

As Day One approaches, the team is focused on checking off every item to be accomplished for a smooth customer and employee transition. When the team has performed well, Day One is a busy, and rewarding day. The team makes sure that everything is executed as planned and business continues uninterrupted — customers’ orders are filled, employee pay is distributed, and e-mails are answered. The two organizations are now functioning as planned.

But there’s still a lot of work ahead: synergy targets must be met, and all the temporary work-around solutions must be replaced with truly integrated systems and processes. The integration team must be reconstituted — new members recruited and existing ones reenergized. By this point, the “us and them” mentality has dissipated — all team members now represent one organization.

Be aware of the mood: The team experiences a huge sense of relief and accomplishment following the flurry of work leading up to Day One. The mood is upbeat and celebratory. But following this rush of excitement, expect fatigue to follow when the team realizes that another push is coming — it is now time to execute the integration plans.

Mind shift required: The team must adjust to a revised pace and longer timelines — more of a marathon to reach the organization’s end state, rather than the sprint towards Day One. After working on quick fixes that allows the combined company to function on Day One, the integration team must recognize their unique opportunity to make a profound and lasting impact on the future of the organization. There are some key actions you can consider taking in your efforts to achieve the mind shift:

• Celebrate success. Whether it is a simple champagne toast in the conference room or dinner at the best restaurant in town, executive leadership should host an event to celebrate and acknowledge the contributions made by the integration team. This is also an opportunity to recognize individuals who made exceptional contributions.

• Reflect and regroup. Bring the team leaders together to reflect on what went well and what they will do differently next time. Before any departing team members leave, be sure that their knowledge and tools are captured and documented for future use. These lessons learned may be applied during the ongoing integration execution or during future acquisitions.

• Take a break. Once Day One is accomplished, everyone deserves some extra time off to catch up on personal activities, spend time with their family, or simply sleep until noon.

• Reset expectations during a team end-state planning meeting. This meeting signals an important shift in the team’s focus toward fulfilling leadership’s end-state vision and meeting synergy targets. The integration leader should kick off this planning session by acknowledging team members’ past contributions and introducing new team members. Ideally, executive leadership should be present to reinforce their vision for the future organization and the importance of the integration team’s role in fulfilling this vision.

Making it all worthwhile

Following Day One, the integration team’s job is to actualize the original vision set forth when the transaction was conceived, meeting the synergy targets, and capturing the value promised to the organization’s stakeholders. When leadership has done its job well, the organization has an added bonus: a highly functioning integration team who understands and supports the end-state vision, with the collaborative work style, discipline, and broad perspective needed to achieve even better results from the next pressure cooking transaction.

Getting past the hostility

Five key strategies designed to help integrate reluctant employees following a hostile takeover

By Kevin Knowles, Kimberly Storin, Danielle Feinblum and Stephanie Meyer

Prepare yourself for the unknown. Overcoming the challenges associated with acquiring and integrating an organization after a bitter proxy fight and hostile takeover will test your leadership abilities, as well as those of your management and integration teams. It is very likely that this transaction will demand a higher level of strategic thinking, flexibility, and innovative problem-solving than any transaction your organization has ever tackled.

Many of these challenges directly affect employees. Be prepared to defuse tension as you ask the acquired organization’s leadership team and employees to commit to your company’s terms and conditions, values, and mission. To further complicate matters, your team will have limited information about the target organization, its leadership, and its employees, which hinders integration efforts.

There is good news, however. We have found that executive leadership can increase the probability of retaining top talent, delivering growth, and capturing synergies in a hostile takeover scenario by incorporating the following five people management strategies.

Use the time prior to transaction close to develop an integration strategy and project management structure.

Five key people management strategies

Strategy #1: Use time wisely

Engaging in a hostile takeover means leadership will have limited access to information about finances, employees, organization structure, and company operations during due diligence. As a result, extensive due diligence and development of a synergy capture strategy and plan cannot occur until postclose. Use the time prior to transaction close to develop an integration strategy and project management structure. This will help enable a quick ramp-up once the transaction closes, accelerating synergy capture.

• Develop integration scenarios. Expedite the integration process by crafting a primary integration scenario, as well as various alternatives. Launch the integration team before the transaction is signed. Begin with a draft operational model and governance structure. Identify integration teams from your organization and aggressively conduct one-sided planning. After close, swiftly engage a broader two-sided planning and implementation team. It is important to maintain flexibility and fluidity, as new information gathered postclose will surely impact the integration plans and roadmap.

• Prepare for Postclose due diligence. Create a comprehensive checklist of all data and practices necessary for quickly assessing and controlling the business on Day One.1 In one-sided planning teams, prepare people to physically take ownership and accountability for all aspects of the acquired business. Usually the transition of ownership is uneventful, but rigorous planning for all scenarios is necessary.

• Understand applicable regulation and labor laws. If the target operates in countries where your organization does not have operations, it is wise to spend time prior to close researching local labor laws to expedite Works Council approval or other labor processes.

• Hot topic scenario planning. Work with your leadership team to develop contingency plans in case the integration does not go as planned. For example, how would the leadership team handle a mass exodus of the acquired employees? What happens if the approval is significantly delayed? What if there is significant negative media coverage? A comprehensive scenario planning exercise can prepare the integration team to shift gears quickly as the situation changes.

Strategy #2: Stabilize the organization

Employees acquired in a hostile takeover will usually have intensified fears about job security, a changing work environment, and the future of the company. Your top priority should be to address employee concerns and minimize uncertainty in order to maintain business as usual. To help accomplish this, consider quickly announcing the top leadership team and actively engaging employees as part of the new organization.

• Select leaders. Given the lack of communication with target leadership prior to close, leadership selection must become a priority immediately at close. It is important to consider loyalties that exist within the target company. For example, if you decide to let a leader go, will loyal employees follow? Will the departure have a major negative impact on morale? Or could the appointment of a leader to a position have a positive impact on morale and how can you leverage that potential goodwill?

Once the leadership team is identified, gain their commitment and focus through the use of new employment agreements and a performance-based retention program.

• Engage employees. Take steps to identify top talent early and create targeted strategies to keep people engaged, transfer unique knowledge, and keep a laser focus on key priorities. After the close of the transaction, review the most recent management performance talent assessments to identify managers with influence across the organization. Implement aggressive change management and communications tactics to leverage these managers to help set the tone for the integration and communicate informally with employees.

• Cultural differences may impede employee engagement following a hostile takeover. One way to identify potential areas of cultural differences before the close is to scour industry blogs, recruitment boards, employee web pages, and other public domain references. Understanding cultural similarities and differences across the two organizations can help you design and launch initiatives that will resonate with employees.

Strategy #3: Accept no leadership dissent

Proxy fights can be long and drawn out, giving the target company’s leaders time to voice negative opinions regarding the takeover and your organization. Once the transaction is closed, it is important to quickly rally them around the organization’s mission, vision, and strategy.

To understand their interests and concerns, consider holding one-on-one interviews with key leaders throughout the target organization as soon as possible after close. Use the information gathered to develop materials for leadership alignment sessions and communication materials. Additionally, a Leadership Summit held immediately after the close can provide an opportunity to influence leaders from both organizations. Encourage leaders to be vocal about the positive aspects of the transaction while maintaining a sense of realism, since some employees may view this as an artificial effort. This balance is essential to establish a transparent line of communication with employees. Aligning leadership and arming them with key messages and tools that help them to be relevant, credible, and authoritative can help to change perceptions among the employees. However, if a leader vocalizes negativity and undermines the ability to engage the broader organization, then quickly remove that leader from the organization.

Be prepared for challenges both before and after close.

Strategy #4: Communicate to influence

Managing external and internal communications is critical to success during a hostile takeover. Negative media coverage during the proxy battle may have negatively influenced customers, partners, community, and employees. Postclose, it is imperative to establish transparent, timely, and consistent communications with key stakeholders to reverse any negative perceptions.

• Consider timing. Timing of communications is especially important following a hostile takeover. Tightly manage the information disseminated to the media so that employees and customers do not first hear about it in the news. Directly hearing information from leadership can help establish trust and credibility with employees and customers, which is key to maintaining business as usual during the integration.

• Communicate often and in a variety of ways. Make sure all employees receive critical information by using multiple communications vehicles, leveraging existing mediums (i.e., e-mail, portal, leaders, and scheduled conference calls) and cascading through managers during team meetings where possible. Additionally, encourage regular feedback from employees by hosting forums where employees can ask leadership questions either live or virtually. Swiftly address this feedback and actively communicate resolution.

• Remember your current employees. Following a hostile takeover, it is easy to overlook the needs and concerns of current employees. Current employees can be highly vocal following an acquisition and can influence perceptions of acquired employees. Factor them into your communications planning and get them involved in the development and delivery of targeted initiatives and messages when possible.

Strategy #5: Recognize that some things are out of your control

A hostile takeover will present leadership with unforeseen challenges, many of which can be prepared for during the scenario planning exercises. Yet even with detailed scenario planning, many things will be out of your control.

For example, timing of the court’s decision and shareholder voting process may be delayed, making it difficult to estimate when the transaction will close. Create an integration plan that is robust, yet flexible, and allows for multiple activities to occur simultaneously. Empower the integration team to make decisions in order to address any unexpected delay, acceleration, or challenge.

Be prepared for challenges both before and after close. Prior to close, you may hear rumors of leadership and employee attrition to competitors. There must be a solid retention strategy and program in place beginning Day One to help retain critical talent. After close, you may uncover surprises related to missing or inaccurate employee data. It is important that you are prepared to begin engaging new employees on Day One, regardless of the challenges in the back office.

When the hostility passes

Acquiring an organization through a hostile takeover presents leadership with unique organizational and people challenges. By recognizing and addressing these challenges early and aggressively, you can help the business and the integration teams maintain focus on the key objectives throughout any proxy fight and court approval process. When the transaction does close, the integration team should be prepared to ramp-up quickly to integrate the people, the business processes, the technologies, and ultimately accelerate synergy and growth objectives.

Section 3: Integration

Prevent costly turnover and lost productivity through effective leadership, communications, and implementation of the integration plan.

Human Resources Management handbook for acquisitions

By Kevin Knowles and Eileen Fernandes

Human Resources (HR) Management has several essential functions in the execution and delivery of an acquisition or divestiture. These include:

HR’s mission in supporting acquisitions:

• Identify, evaluate, and dispose of transaction-related concerns

• Serve as the primary point of contact for HR processes

• Deliver a single coordinated employment solution for acquirer, acquired, or divested company

HR Management support of an acquisition supports six primary objectives:

• Execute the transaction

• Maintain organizational focus

• Retain key skills

• Accelerate employee engagement and affiliation

• Recruit new talent

• Effective transfer of unique knowledge

Core HR merger and acquisitions (M&A) processes:

1. HR infrastructure and systems

– Compensation

– Cash

– Stock

– Executive

– Benefits

– Talent management

– HR information systems (HRIS)/Payroll

2. Effectiveness

– Organizational development and change management

– Workforce transition

– Leadership development

Human Resources Management contributions

HR’s role during the transaction is to lead decision processes, execute the transaction, and prepare the company for integration. A representative of HR should be assigned to the transaction and take accountability for transaction decisions, as well as build relationships with the target company.

HR’s primary collaborators in a transaction are business unit management, transaction leaders, finance and control representatives, and legal representatives.

Acquisition transactions begin with preliminary assessment (pre-due diligence) of a target and conclude with the execution of all items in the Purchase Agreement. The following are four primary areas where HR supports a transaction:

1. Pre-Due diligence

– Valuation

– Retention cues and capability

– Assessment of leadership and culture framework

2. Due diligence

– Validation

– Assess risk and liability

– Integration planning and readiness

3. Retention planning

– Employment arrangements

– Criticality assessment of individuals and jobs

– Agreement to retention framework and concepts

4. Process and agreement support

– Preliminary terms (term sheet, letter of intent)

– Purchase agreement

– Stock repurchase agreements

– Stock option conversion

– References related to “termination with cause” or other employment

Pre-Due Diligence