Publications HR In International Mergers And Acquisitions

- Publications

HR In International Mergers And Acquisitions

- Bea

SHARE:

By Tony Edwards, Ali Budjanovcanin and Stuart Woollard – CIPD

Summary of key findings

This research has been conducted against a backdrop of a rising number of firms engaging in international mergers and acquisitions (M&As). Previous research for the CIPD has charted some of the HR challenges involved in these deals and the report seeks to extend our understanding of these challenges by drawing on data from a major new survey of multinational companies (MNCs) in the UK. The survey covers 302 firms, the largest group being overseas-owned companies with more overseas employees than UK-based ones, and the other group is UK-owned MNCs with at least 500 employees, of which at least 100 are outside the UK.

The HR function

• Despite international M&As bringing a range of issues that HR practitioners must confront, the HR function is smaller in firms growing in this way than in firms growing through ‘greenfield’ investments and is no bigger on average than those firms that had not grown at all. This raises questions concerning the resourcing of the HR function in firms growing through international M&As.

The characteristics of HR policies and practices

• The report indicates that firms growing through acquisition are significantly constrained in handling pay and adopt a pragmatic approach to union recognition. They tend to devote fewer resources to training (albeit with national variation in this respect) and do not communicate more intensively with their workforces than other firms.

Organisational learning

• Making acquisitions in other countries is one way in which firms can absorb expertise and new practices, yet the data suggest that many firms are not successfully tapping the diversity of practice that international acquisitions bring. This has clear implications for the performance of firms growing in this way.

Background

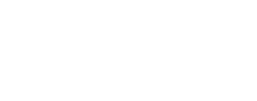

The last few years have witnessed a sharp increase in international mergers and acquisitions (M&As). These tend to be cyclical, fluctuating markedly with the business cycle. Thus the wave of deals in the years leading up to the end of the last century was followed by a sharp slowdown between 2001 and 2003. By the end of 2005 they had recovered to levels close to the previous peak (see Figures 1 and 2) and almost certainly established new record levels in 2006.

The pick-up in international M&As is important for HR practitioners for a number of reasons, not least because there are some issues that must be confronted in all cross-border mergers, such as carrying out a due diligence process, compliance with TUPE legislation and communicating the key consequences of the merger to the workforce (for further details, see the CIPD guide (2003), International Mergers and Acquisitions).

Previous CIPD research has demonstrated that the way these issues are handled is strongly conditioned by the nature of national systems. One aspect of this is that the nationality of the dominant firm in a merger or acquisition leads to a ‘country of origin’ effect, while another aspect is the distinctive institutions and culture of each national system in which the merger takes place that creates a ‘host country’ effect. For example, American firms making acquisitions in the UK appear to move towards integrating acquired operations into the parent companies more quickly than those of other nationalities, but are constrained to some extent in doing so by UK regulations and traditions in employment. This research also showed that the handling of HR issues during international M&As is highly political in the sense that a lot of key decisions reflect the competing interests of different groups within the merged firm. Hence, the way that a lot of issues are resolved is through negotiations and compromises between different parties to the merger. A prime illustration of this is the way that senior positions are often divided up in proportion to the size of the parties to the merger, meaning that they are not filled solely by merit (CIPD 2003).

These findings raise further issues, three of which are addressed in this report:

• First, given the challenges of international M&As, are the HR functions of firms that grow in this way different from those that don’t grow through acquisition?

• Second, to what extent are the effects of a merger or acquisition evident in the nature of HR policies in the merged firm?

• Third, if international M&As are highly political, how does this affect the process of organisational learning, particularly the extent to which firms learn from their acquired operations?

These questions are addressed through analysis of data from a major new survey of multinational companies in the UK. The details of this survey are elaborated upon in ‘The characteristics of firms going through a merger or acquisition’, and the basic characteristics of the firms are summarised briefly in ‘The characteristics of the HR function and the method of growth’. The three questions identified above are then tackled in the subsequent sections, and the conclusions drawn in ‘Conclusions and implications’.

The survey

The analysis of the survey data is the first stage of two in an ongoing research project. It has served two main purposes. The first has been to provide an authoritative picture of the nature of MNCs that have made acquisitions in the UK, shedding light on the nature of the HR function, the characteristics of HR policies and the process of organisational learning. It has produced some intriguing, maybe even troubling, findings. One key finding is that, despite the inherent challenges of growing through acquisition and the demands that stem from being part of a co-ordinated approach to HR across borders, the HR function was smaller in firms that grew in this way.

The survey on which this report is based is the most comprehensive and nationally representative survey of employment policies and practices in MNCs in the UK. It is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and is co-ordinated by a team of academics from Leicester Business School, Warwick Business School and the Department of Management at King’s College, London.

The preparatory work involved the establishment of a full listing of all MNCs in the UK, which surprisingly did not exist previously. The survey itself was then in two stages. The first was a short telephone interview with an HR practitioner that served to check the accuracy of the listing and to add in some fresh data on issues such as the structure of the company and the nature of the HR function. These interviews were carried out in 903 companies. The second and main stage was a lengthy face-to-face interview with the UK HR director in 302 of the companies. It’s this latter stage that forms the dataset on which this report is based.

The survey covers two groups of MNCs. The largest group – accounting for 257 of the 302 firms in the main stage of the survey – is overseas-owned companies with at least 100 employees in the UK and at least 500 worldwide. The other 45 firms are UK-owned MNCs with at least 500 employees worldwide and at least 100 of these outside the UK. To some extent the questionnaires used for each of the two groups differed to reflect the fact that, in the former, respondents sat at the level of a national unit of a multinational, and in the latter they sat at the corporate head office. This report is based primarily on the 257 overseas-owned firms (all of the figures relate to this group), though some reference is made to the UK MNCs.

The survey sheds considerable light on the issue of M&As. Most fundamentally, firms were asked whether the firm had grown in the UK through a merger or acquisition in the previous five years. Where they had, they were then asked some supplementary questions such as whether the merger or acquisition changed the nationality of the firm. One distinctive aspect of this study is that it’s not a study of the acquired operations themselves but rather of the wider firms making the acquisitions. While this means that it doesn’t provide data on the changes to HR practice in sites that were acquired, it reveals much about the characteristics and policies of firms growing in this way.

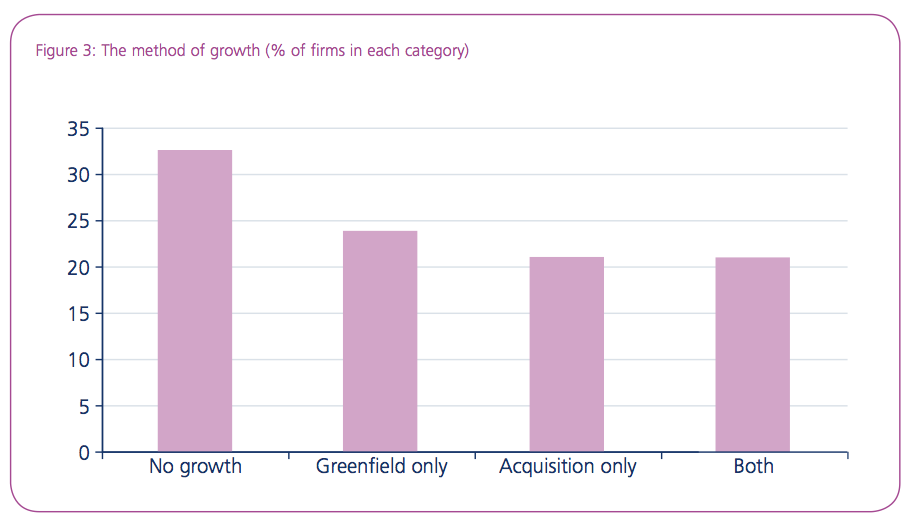

Throughout much of this report we distinguish between four types of firm:

• those that have not grown at all

• those that have grown only ‘organically’ (through ‘greenfield’ investments)

• those that have grown only through acquisition

• those that have grown both organically and through acquisition.

We report differences between these groups and highlight whether or not these are statistically significant throughout.

The characteristics of firms going through a merger or acquisition

The survey provides one measure of the extent of acquisitions among multinational companies in the UK.

In total, 107 of the 257 (42%) overseas-owned firms surveyed had made an acquisition in the five years prior to the survey. Of those making an acquisition, this constituted the whole of the UK operations in just over two-fifths of cases.

For the UK-owned firms, there are data relating to acquisitions in the UK and internationally. Just over six out of ten (61%) of this group had made an acquisition in the UK in the five previous years, and an almost identical proportion (62%) had made an acquisition outside the UK in this period. Half of the UK MNCs in the study had made acquisitions at both home and abroad. Of those making international acquisitions, the vast majority (89%) already had operations in other countries prior to the growth in the previous five years.

The survey also allows us to distinguish between companies according to whether they have grown and how they have grown. Just over a fifth (21%) of overseas-owned firms in the UK had grown only through acquisition, and an identical proportion (21%) had grown both through acquisitions and through greenfield investments. Just under a quarter (24%) had grown through greenfield investments only and the remaining third (33%) had not grown at all. We use the four-way distinction depicted in Figure 3 throughout the report.

It’s important to consider the basic characteristics of firms that are associated with growth through acquisition. This is partly because it’s interesting in its own right to establish which type of MNCs grow in this way, but it is also important because, if there are

systematic differences between the four groups of companies in Figure 3 in terms of size, sector, nationality and so on, then these should be borne in mind in interpreting the analysis that follows concerning the nature of HR policies in each type of firm.

There were some ways in which the profile of the firms in the four categories differed. For example, service firms more commonly grew through acquisitions. By size, the companies growing through both mechanisms were the largest by both UK and worldwide employment. Companies that had grown through acquisitions were younger on average.

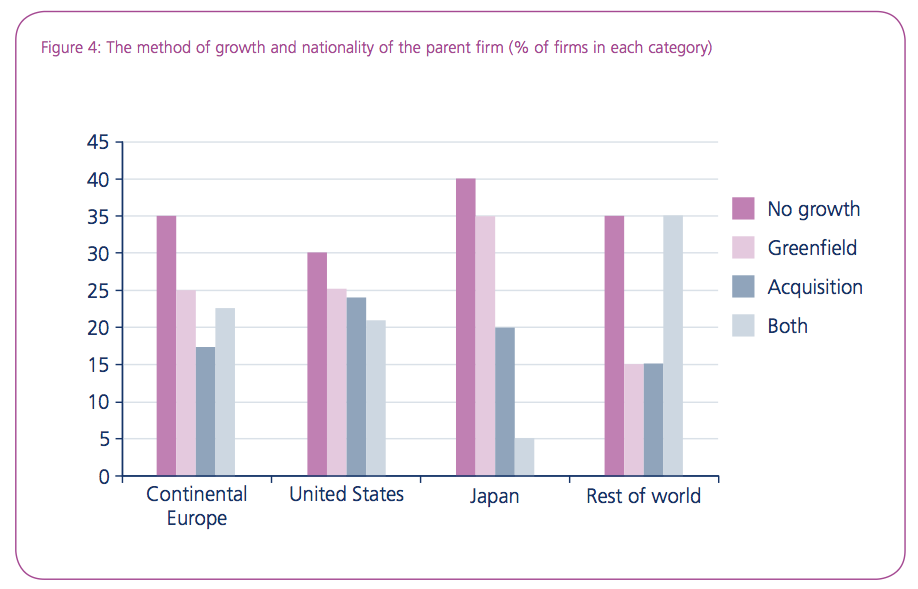

In other ways, the profile of the firms in the four categories was similar. One very important aspect of this was the national profile. Fewer of the Japanese firms in the survey grew at all, and those that did tended to grow through greenfield investments rather than acquisition, but these differences were not significant.

Moreover, the extent and forms of growth in the two main groups – American and continental European – are very similar (see Figure 4). The pattern of growth was also similar in companies with different levels of diversification across sectors, different approaches to standardising or adapting their products or services across countries, and different ways of achieving international integration across countries.

In summary, the profile of firms making acquisitions is that they are more likely to be in services, to be younger and to be larger. We return to discuss the possible significance of this in later sections, for example by considering whether systematic differences in HR policy between acquiring and non-acquiring companies can be interpreted as flowing from the form of growth or whether they might reflect the sector, age or size of the firms. It’s also noteworthy, however, that there were not significant differences by nationality, diversification, standardisation or integration.

The characteristics of the HR function and the method of growth

The survey allows an assessment to be made of some aspects of the HR function in acquiring firms and to contrast this with the other groups. These include the size of the UK HR function, the extent to which there is an international dimension to the HR function and an indicator of control over HR in the UK from higher levels within the company.

The size of the HR function in the UK

Growth through mergers and acquisitions brings with it particular challenges for the HR function, not least of which is the process of post-merger integration. So one issue of interest is the size of the function, since this provides an indicator of the resources devoted to HR. This is measured through the proportion of the UK workforce that is made up of managers who spend the majority of their time on HR matters. The average for the overseas-owned firms as a whole was exactly 1%. Perhaps surprisingly, those firms that had made a merger or acquisition in the previous five years had a lower average (0.72%) than those that had not grown in this way (1.19%). It may be that this is explained by the size of firms; bigger companies tend to have a lower proportion of HR staff to total employees.

However, analysing the data by the four categories identified in the previous section revealed a further curious dimension to this issue. Figure 5 demonstrates that by far the largest HR functions were in firms growing through greenfield investments alone. In contrast, companies that grow through acquisition alone, despite being bigger on average than those growing through greenfield investments, tended to have proportionately smaller HR functions. Moreover, the HR function in firms that grew through acquisition alone were no bigger on average than those that had not grown at all. This raises questions concerning the resourcing of the HR function in firms growing through international M&As.

The international dimension to the HR function

The survey also sheds some light on the extent to which the HR function is international in orientation. That is, does the function have mechanisms for gathering data, forming policies and exchanging experiences in an internationally co-ordinated way? And does this tendency differ between firms according to how they have grown? This provides an indication as to whether the acquiring firms seek to integrate their acquired units into the wider international firm, with all of the challenges that this brings. Alternatively, it may be that MNCs growing in this way tend to take the apparently simpler approach of leaving their acquired units in different countries to their own devices, as would be the case in the stereotypical holding company.

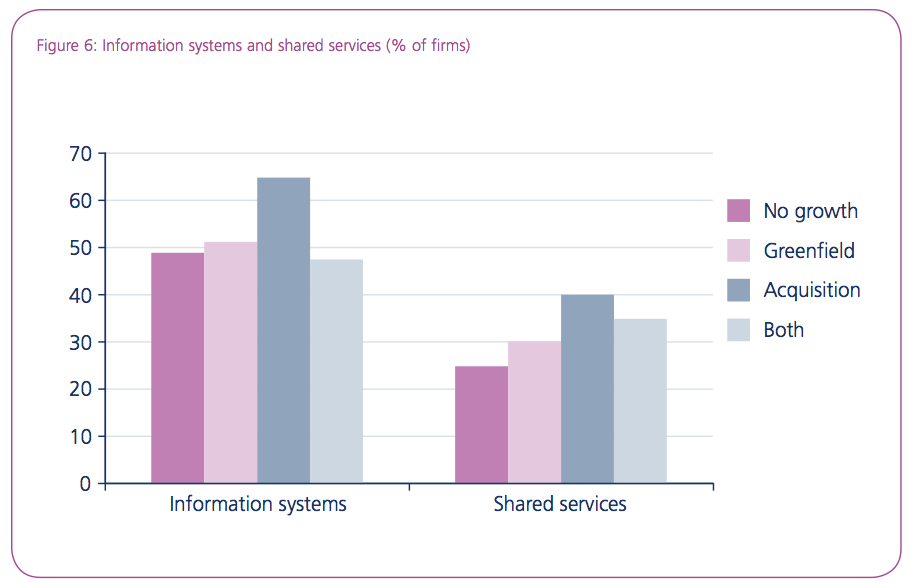

Our survey explored four dimensions. The first dimension is whether there was an HR information system concerning the firm’s international workforce. Among overseas-owned MNCs, such a system was most commonly found in firms growing through acquisitions only (65%). The second dimension was whether the HR function makes use of ‘shared service’ centres at the international level. This too was more commonly found in firms making acquisitions (40%) than in the other groups. See Figure 6.

The third aspect to the extent to which the HR function is international in outlook concerns policy-making across borders, specifically whether there was an international HR policy-making body. The data show that MNCs that have grown through acquisition alone were those most likely to have such a body in place (58%). Since larger firms were more likely than smaller ones to have a committee, it could be that size rather than method of growth lies behind this pattern. However, little difference was observed between the no-growth category of organisations, which were the smallest, and the other two growth categories (greenfield investment only and both forms of growth), which were larger, suggesting that this is not an influential factor.

The fourth dimension concerns the extent to which the firms made a systematic attempt to bring together managers across sites in different countries at the global level, which is a good indication of whether an organisation is characterised by an international network in HR. The data show that it is the firms that have grown through acquisition only that were the most likely to engage in this form of networking (62%). See Figure 7.

In all four aspects, therefore, firms growing through acquisition appear to be those that were the most likely to adopt an internationally co-ordinated approach to HR. There are two qualifications to this assessment, however. The first is that all four of these associations fall short of accepted levels of statistical significance. (These statistical significance tests provide a way of judging whether an association between variables is a genuine one or whether the pattern in the data simply occurred through chance.) The second is that we know that larger firms in general were more likely to have an internationally co-ordinated approach to how the HR function operates and that this may explain some of the differences that were observed (though not all of them, as noted above). At the very least, however, it seems safe to conclude that firms growing through acquisition in the UK are at least as likely to be required to be a part of an internationally integrated approach to HR.

Control from the corporate head office

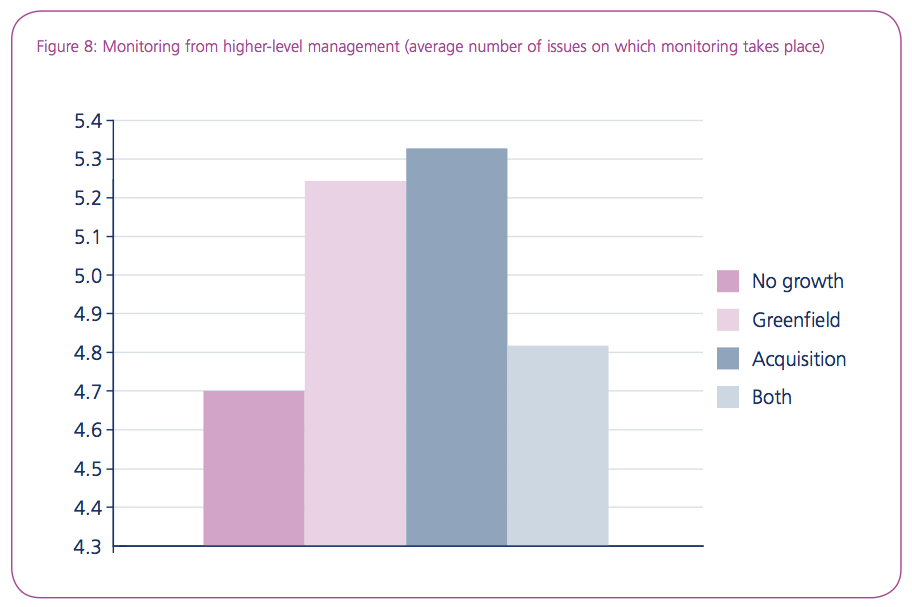

The survey also enables us to make an assessment of the extent to which the parent company intervenes in the handling of HR issues in the UK operations. There are a number of ways of measuring this; here we use the issue of the extent to which the corporate head office requires information on a range of employment matters to be submitted from the UK HR function. The respondents were shown a list of nine HR issues and asked how many of them data were collected about the UK operations by management at the corporate head office. Where the UK operations had encompassed an acquisition in the previous five years, higher-level management monitored on a wider range of issues.

However, the qualifications raised in the previous sub-section are relevant here too, namely that the differences in the mean number of issues on which data were collected between the four categories were not statistically significant and that we know that larger firms are more likely to monitor on a range of issues. Once again, however, a safe assumption would be that companies growing through acquisition are at least as likely as others to be monitored by higher levels of management. See Figure 8.

Conclusion

This section has shed light on various aspects of the HR function, with these sitting uneasily alongside one another. On the one hand, the HR function in firms growing through acquisition in the UK is smaller than in other types of firm. This in itself is a surprising finding given the challenges that are inevitably faced by HR in M&As, one of which is the pressure to restructure the function across the merged firm. On the other hand, the data indicate that one dimension of this restructuring is that the HR function in the UK is at least as integrated into an international HR function in firms growing through acquisitions as in other types of firm and that the UK operations of firms growing through acquisitions are no less likely to be subject to reporting requirements from higher-level managers. Overall, then, the picture that emerges from the UK operations of firms engaging in international M&As is one of a relatively small HR function despite the inherent HR challenges that they bring, and that these challenges are coupled with the requirements of being part of a co-ordinated international function and of being monitored from higher levels that are at least as strong, and maybe stronger, than in firms that either have not grown or which have grown through greenfield investments.

HR policies in acquiring firms

This section analyses data relating to a range of HR policies, particularly those in the area of pay, training, employee involvement and employee representation.

The survey included questions on these issues in relation to three groups of staff: managers; the ‘key group’, which was defined as those that are ‘critical to your company’s core competence’; and the largest occupational group (the LOG).

Pay

The handling of pay and benefits is of course one of the key HR issues in international M&As and may be an indicator of a firm’s management style. Many acquisitions are justified on the basis that there will be cost savings that can be realised, which we might expect to lead to downward pressure on pay. However, previous research on this has been inconclusive, with some evidence suggesting that pay levels tend to rise modestly following changes of ownership (Bruining et al 2005). In relation to how pay is determined, some previous evidence has indicated that regardless of their nationality, companies look to implement performance-related pay (PRP) in their acquired units (Faulkner et al 2002). While there may be general patterns in managerial preferences in acquiring companies, pay and benefits are also subject to significant constraints through the Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) (TUPE) Regulations in all firms, and by collectively bargained pay structures in unionised firms. So what does the survey data tell us about levels of pay and how it is comprised?

On the first of these issues, respondents in overseas-owned firms were asked about their policy on pay levels in relation to market comparators for each of the three groups for the whole of their UK operations.

Figure 9 shows that there is little difference in the pay strategy for the LOG between companies according to how they have grown. For the key group and for managers, the proportion aiming to be above the median is moderately higher among firms growing through acquisition compared with those not growing. Overall, the survey data does not suggest that firms growing through acquisition systematically aim to reduce pay as a way of meeting cost-saving targets.

The analysis for UK-owned MNCs is constrained by the relatively small numbers (45) and by the questions for this group being restricted to managers and the LOG. Nevertheless, the data reveal a similar pattern. There are only modest differences in the pay strategy for the LOG and for managers. The proportion of firms that had made an acquisition overseas that aimed to be above the median for managers was significantly higher when compared with those firms that had not made an international acquisition.

This evidence on pay levels, therefore, suggests that firms growing through acquisitions do not aim to pay less than other firms in order to realise cost savings. Indeed, it indicates that for some groups of workers they are at the higher end of the spectrum. A plausible interpretation of this is that the constraints on pay levels that they face lead firms to seek to realise cost savings through other means, such as redundancies.

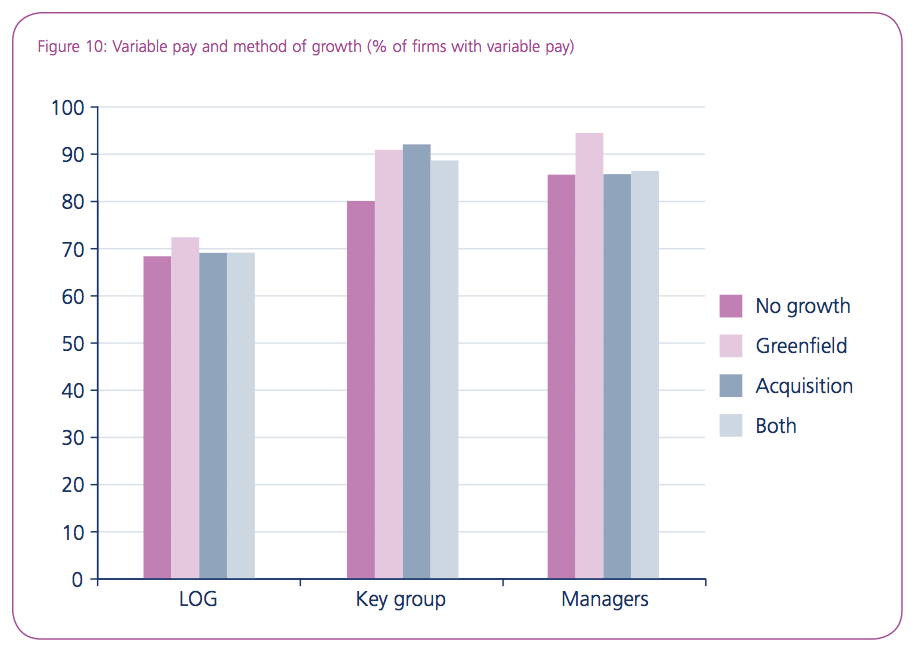

On the second issue, respondents were asked whether there was variable pay – with this being defined as ‘merit pay, performance-related pay, performance-related bonuses or payment by results’ – for each of the three groups. In each case, as Figure 10 indicates, there were no significant differences between how firms had grown and the use of variable pay. (It was also the case that there were no significant differences in the use of variable pay between UK-owned MNCs according to how they had grown.) Given the previous research on this issue, this is a surprising finding. It should be remembered that this survey asks about all of the UK operations as opposed to just those that were acquired. However, the lack of a clear difference is all the more surprising given that variable pay is more common in services, the sector in which the survey indicated variable pay is most commonly found and in which international M&As are disproportionately located. The absence of any systematic differences according to how firms have grown lends further weight to the notion that acquiring firms are significantly constrained in changing pay and benefits.

There is, however, some limited evidence of growth by acquisition being positively and significantly associated with some particular forms of pay and benefits. Specifically, overseas-owned firms that had made an acquisition in the UK were more likely to have profit-sharing for the key group and the LOG and were also more likely to have share ownership schemes and share options for managers. The data for UK MNCs also shed light on this. UK companies that had made an acquisition overseas were more likely to have share ownership schemes, profit-sharing and share options for both the LOG and managers in the UK. Taking the evidence for these two groups, it is suggestive of a pattern of acquiring companies favouring profit- and share-based bonuses and it is reasonable to suppose that the handling of these issues is freer from institutional or regulatory constraints than is basic pay.

In summary, the handling of pay in acquiring companies seems to be heavily constrained. If there are different preferences on the part of managers in firms according to how they have grown, then these do not show through strongly in the way they manage their UK workforces.

Training

The resources devoted to training is another key issue to examine in international M&As since it provides an indication of the strategies of acquiring firms, particularly concerning the extent to which they adopt an approach that emphasises employee development. It might be anticipated that since M&As are often justified on the basis of cost savings that can be realised, then firms growing through acquisition may look to the training budget as a relatively easy way of making cuts. Yet, some previous studies have shown that international M&As led to an increase in training in the acquired units (Faulkner et al 2002), a finding that was also associated with changes in ownership more generally (Bruining et al 2005). What does the survey data tell us?

Given that this is a study of firms, not individual sites, the data for training related to all of the UK operations, not just those that were acquired. This is useful insofar as it tells us about the wider approach that the companies take and also because the pressures that stem from cost-saving targets are likely to apply across the firm. Respondents were asked what percentage of the annual pay bill in the UK company was spent on training and development for all employees in the previous year. Unsurprisingly, not all of them knew the figure, so the analysis is for 155 companies on this issue. The data for the four categories of firms are in Figure 11.

The main pattern here is of a lower training and development spend in those companies acquiring, whether this be the only way they grow or whether it is combined with growth through greenfield investments (although the differences between the groups fall short of being statistically significant). The picture for UK MNCs is similar. The difference in the percentage of the annual pay bill devoted to training between those companies that had made an overseas acquisition (3.7%) and those that had not (5.8%) was particularly pronounced (though the small numbers providing data meant that this was not statistically significant either).

The data, then, don’t support the findings of some previous research, which found that international M&As were associated with increased training. Rather, they seem to indicate that the training budget is one that is curtailed in the post-acquisition period as the company comes under pressure to make cost savings. However, the data by nationality of the parent revealed marked differences between these groups. Among overseas-owned MNCs that had made an acquisition in the UK, German companies invested significantly more in training and development (6.9%) than American (3.1%), Nordic (2.3%) and Japanese (1.7%). Thus the finding that the resources devoted to training was lower in acquiring firms is one that needs to be qualified to take into account the influence of nationality.

Employee involvement and representation

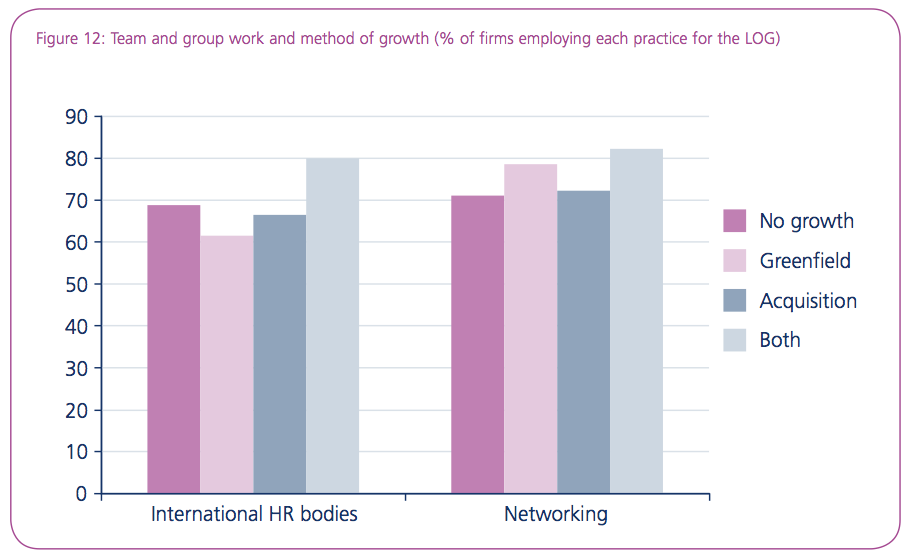

Some previous research has indicated that international M&As are associated with an increased use of teamwork, especially where Japanese or German firms are the acquirers (Child et al 2001). Respondents in our survey were asked whether they used ‘formally designated teams in which employees have responsibility for organising their work’ and ‘groups where employees discuss issues of quality, production or service delivery’. Both ‘teamwork’ and ‘group work’ were widespread, but were not significantly more common in firms growing through acquisition (see Figure 12). One relevant factor in interpreting this finding is that the survey shows that these practices are more common in manufacturing, and the acquiring firms are disproportionately in services.

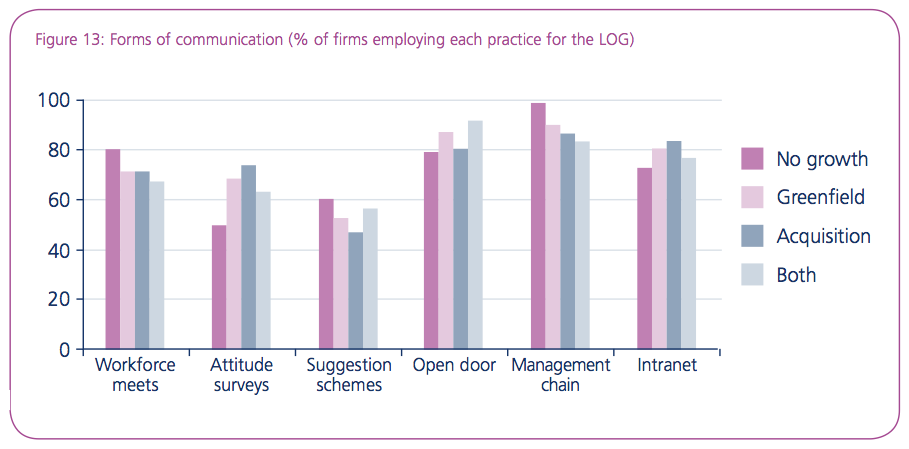

The survey also sheds light on the issue of communication between managers and the workforce. Previous research for the CIPD has emphasised the importance that HR places on communication in acquisitions (CIPD 2003). There were two dimensions to this that could be examined in the data. The first was the forms that communication took. Figure 13 shows the prevalence of six types of communication and demonstrates that there are few differences between firms according to whether and how they have grown. Attitude surveys were significantly more likely to be used by firms growing through acquisition, but systematic use of the management chain was actually less common in firms that had grown. The differences for the other four forms of communication were very modest.

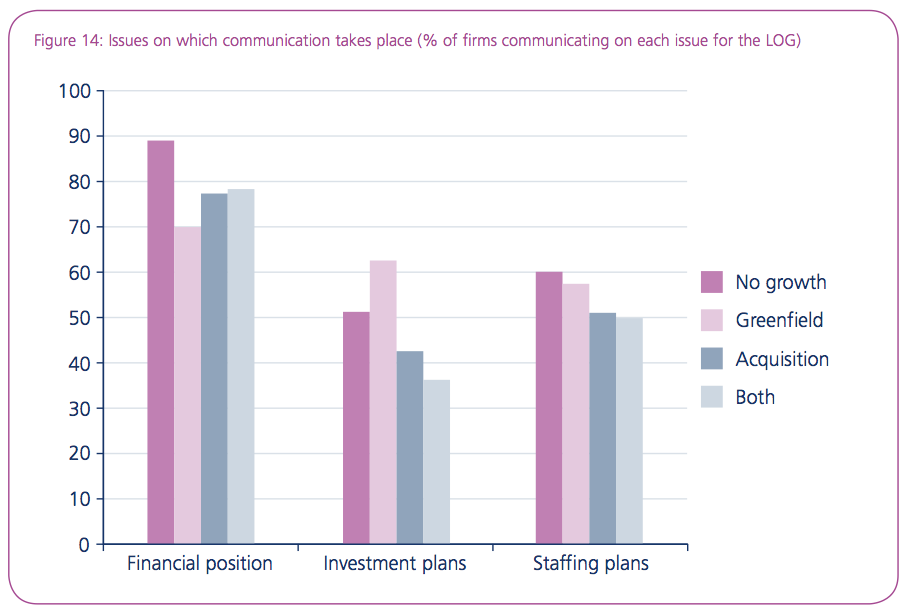

The second dimension to communication concerned the extent to which firms regularly provided information to the LOG about three issues. The picture here is that firms growing through acquisition were not associated with greater communication (see Figure 14). Indeed, they were significantly less likely to disclose information on investment plans, and growing firms in general were less likely to disclose information on the financial position of the firm.

The findings on communication are surprising. Despite regular communication being widely seen as central to avoiding discontent and misunderstandings in M&As, firms that grow in this way do not communicate more than other firms. The obvious qualification is that this does not ask about practice in acquired units at the time of the acquisition but rather the more general characteristics of groups of firms. It should also be noted that the survey indicated that information disclosure was more common in manufacturing, whereas acquiring firms are disproportionately in services. Nevertheless, it’s noteworthy that the requirements to consult and the widely held view concerning the importance of communication in acquisitions is not reflected in practice in companies that grow in this way.

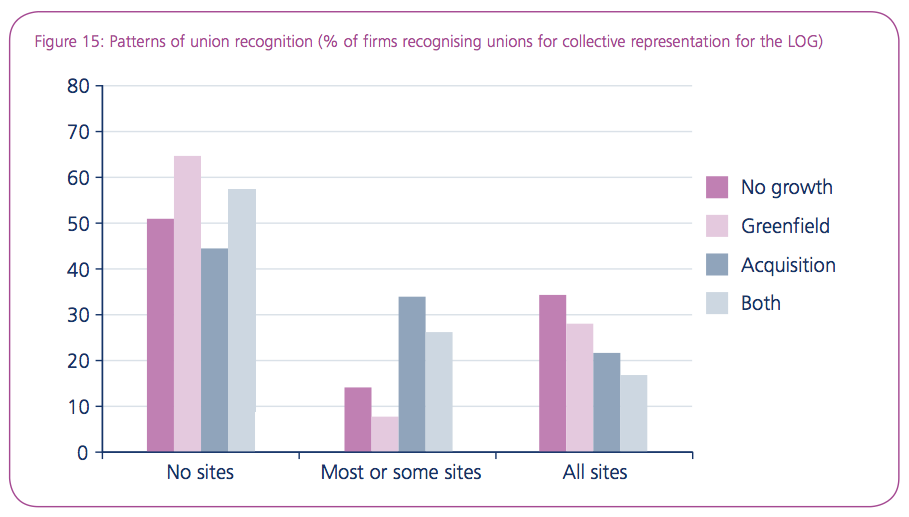

The final aspect addressed of employee involvement and representation is patterns of union recognition. The presence of unions may constrain the course of post-merger integration and it’s conceivable that firms will look to avoid acquiring firms where unions are recognised. Figure 15 overleaf shows the extent of union recognition for collective representation for the LOG in the four groups.

It shows that firms that grow through acquisition were significantly more likely to exhibit some union recognition. This is particularly surprising when it’s set in the context of union recognition being more than twice as common in manufacturing MNCs compared with those in services. Thus the evidence indicated that rather than seeking to avoid unions, acquiring firms adopted a pragmatic approach to this issue. In particular, they were more likely to exhibit a mixed pattern, with unions recognised in most or some sites. In contrast, firms growing through greenfield investment tended to either recognise unions everywhere or not at all.

A subsequent question concerning changes to union recognition specifically in acquired sites provides further evidence of the pragmatic approach of acquiring companies. Of the 106 making an acquisition, there were only five cases of firms saying that union recognition had been withdrawn where it existed previously, and only three saying new recognition had been granted where it had not existed previously.

Summary

This section has been revealing concerning the HR policies in MNCs making acquisitions in the UK. We have seen that they were constrained in their approach to pay, tend to devote fewer resources to training (albeit with national variation in this respect), do not communicate more intensively than other firms and adopt a pragmatic approach to union recognition. In the next section we tackle the issue of the extent to which firms growing through international M&As learn from their acquired units.

Organisational learning in international M&As

The final issue addressed is that of the extent to which international M&As are associated with organisational learning.

Growth through acquisition leads to the firm inheriting a diverse range of practices, giving it the potential to learn from acquired units and spread some of the practices to other parts of the multinational in other countries. This potential is arguably greater than in firms that are not growing or those that grow through greenfield investment. Relatively little is known about how this works in practice and the survey was revealing in some respects.

The survey contained three principal measures of the way in which firms learned from their operations in other countries. The first was derived from a direct question on four areas of employment practice – pay, training, employee involvement and employee consultation – concerning whether the UK company had provided new practices that had been taken up elsewhere in the worldwide company in any of these four areas. Just over six out of ten companies had done so, with this being more common in firms growing at least in part through acquisition.

Second, respondents were asked if they were able to ‘point to global HR policies that are based on those that were originally developed outside the country of origin’. Around four out of ten indicated that they could, with those in acquiring firms once again more likely to do so.

Third, respondents were asked whether the ‘corporate HR function regularly assigns roles in formulating policy to HR managers in the overseas operations’. Just over a quarter said that this did happen. However, this was less common in firms that had grown (either through acquisition or greenfield investment) than those that had not grown, suggesting that where international acquisitions lead to practices being absorbed into the rest of the company, it’s not primarily through a formal process of role allocation from head office, but rather a more informal process of alliance-building and direct contact between HR managers in different sites. It should be noted that none of these three differences were statistically significant, however. The patterns are summarised in Figure 16.

Note: The number of respondents varies from 237 for the first issue, 248 for the second, and 240 for the third. (For the second and third issues, the yes category was created from the merging of the ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ options.)

The picture for UK MNCs is similar, though not identical. Those that have grown through acquisition were significantly more likely to have adopted practices in any of the four areas – pay and performance, training and development, employee involvement, and employee representation – into their UK operations than those that had not. They were no more likely to point to formal global HR policies that had been based on practices developed in other countries, nor to assign roles in policy formation to overseas operations.

The patterns might be interpreted in two different ways. The first is that the survey data indicate that learning from abroad is more common in firms growing through acquisition, indicating that this can be a mechanism through which MNCs inherit new HR practices that are subsequently absorbed into the rest of their operations. A quite different interpretation, however, is that the differences for overseas-owned MNCs between acquiring and non-acquiring firms were modest and not significant, suggesting that those that grow through acquisition are not fully using the diversity of practice that this method of growth presents. Even among UK-owned MNCs, where the difference was significant, only half of firms that had made acquisitions abroad could identify practices that had been transferred to the UK from overseas sites. If this is the case, then it may be that senior managers are not making strenuous attempts to tap into the diversity of practice that international acquisitions bring, or that their attempts to do so are thwarted in some way.

Conclusions and implications

The analysis of the survey data is the first stage of two in an ongoing research project. It has served two main purposes. The first has been to provide an authoritative picture of the nature of MNCs that have made acquisitions in the UK, shedding light on the nature of the HR function, the characteristics of HR policies and the process of organisational learning. It has produced some intriguing, maybe even troubling, findings. One key finding is that, despite the inherent challenges of growing through acquisition and the demands that stem from being part of a co-ordinated approach to HR across borders, the HR function was smaller in firms that grew in this way.

On the character of HR policies, it was intriguing that firms that grew through acquisition tended to devote fewer resources to training (albeit with national variation in this respect) and did not communicate more intensively than other firms. And on organisational learning, the data suggested that, where it occurs, it tends to be through a process of informal coalition-building, and that the scope for learning from acquired units was not fully used.

These are all issues that will also be addressed in the second phase of the research, which will comprise a series of case studies. The benefit of this form of research is that it will allow different aspects of the same phenomena to be addressed. For example, the case studies will permit an assessment to be made of whether and in what ways the role of HR is constrained by the resources devoted to it and whether the tendency to spend less on training matters in the longer term. The case studies will be invaluable in a more thorough consideration of the issue of organisational learning in the post-merger period, something that the survey was able to address in only a rather general way. The details of this research will be available from the CIPD website.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter