Publications Global Corporate Divestment Study – Learning From Private Equity: Experts At Extracting Hidden Value

- Publications

Global Corporate Divestment Study – Learning From Private Equity: Experts At Extracting Hidden Value

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

Our perspective

Roughly half of the companies surveyed for our Global Corporate Divestment Study are considering a divestment in the next two years. Yet many of these companies will struggle to generate maximum value from their divestments. This is all the more reason to share leading practices now — particularly those of organizations that excel in finding value.

Private equity (PE) firms are skilled value-finders. They are serial buyers and sellers, expert at locating hidden upside in companies. They often exit at a multiple that is many times the original purchase price. As key board members, they have an innate understanding of their portfolio companies’ inherent value and whether to continue to invest or if it is time to divest.

While corporations have a different core mission from PE firms, they can learn lessons from PE on how to maximize shareholder value. Corporates face particular challenges in maximizing value from divestments: some companies may be too opportunistic, reacting to an interested buyer rather than thinking strategically about who might be the best acquirer. Many are reluctant to invest management time in an asset they plan to sell, or they may be unwilling to allocate scarce capital to such businesses. Yet by failing to properly prepare assets for sale, companies only make them less appealing to the next owner.

This year’s Global Corporate Divestment Study focuses on the critical lessons corporations can learn from PE to increase divestment success. Our findings are based on interviews with 900 global corporate C-suite executives and 100 private equity executives, as well as external data from nearly a decade’s worth of divestments. (Paul Hammes, EY Global Divestiture Advisory Services Leader)

For the M&A markets, 2015 was the biggest year on record — and divestments were a significant part of that story. The divestment of non-core or underperforming businesses is now widely seen as a key way for companies to fund the next phase of growth.

So what comes next? As we look ahead to 2016, an M&A slowdown appears unlikely. Global economic and policy conditions mean that companies are likely to continue with aggressive moves to protect revenue and market share while boosting margins and profitability. While acquisitions are companies’ most likely response, strategic divestments should also be a top priority.

Moreover, many potential buyers are sitting on large war chests of cash to fund bold acquisitions. Nonfinancial corporates in the S&P Global BMI currently hold more than US$5.4t in cash and equivalents on top of US$1.2t of dry powder from private equity funds. In short, now is an especially good time to evaluate businesses for potential sale or spin-off. (Steve Krouskos, EY Global Deputy Vice Chair, Transaction Advisory Services)

Key findings

Why divest

70% of companies are using divestments to fund growth

84% believe their divestment created long-term value in the remaining business

Portfolio review

56% of companies’ portfolio review processes have resulted in unsuccessful divestments

49% say access to meaningful data is the biggest portfolio review challenge

Execution

75% more companies generate a sale price above expectations when they focus on creating value pre-sale

33% more companies generate a sale price above expectations with an operational separation plan

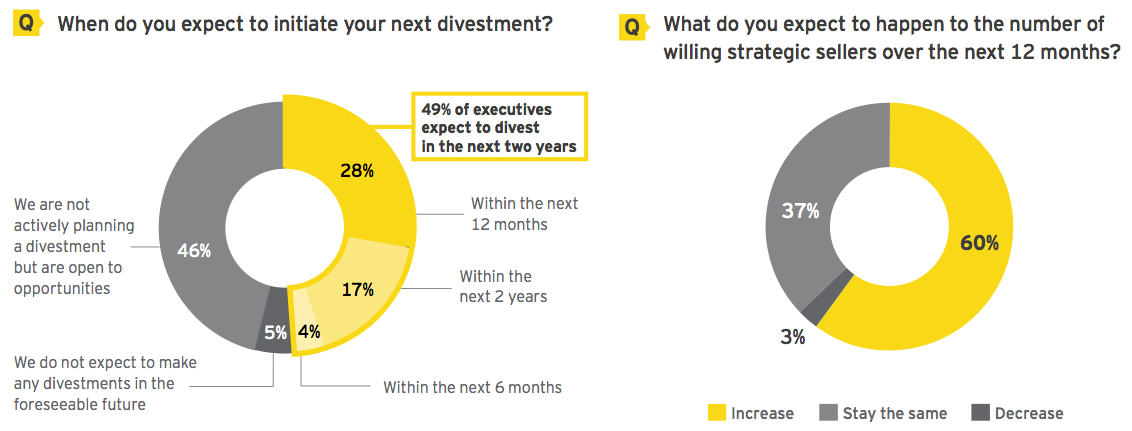

49% of companies are planning to divest within the next two years

1. Are companies achieving their divestment goals?

Considering that all of our study respondents already made a major divestment in the past three years, it is remarkable that nearly half expect to divest again in the next two years. This is an indication of how deeply embedded divestments have become in corporate strategy. Moreover, 60% expect the number of strategic sellers to increase in the next year alone.

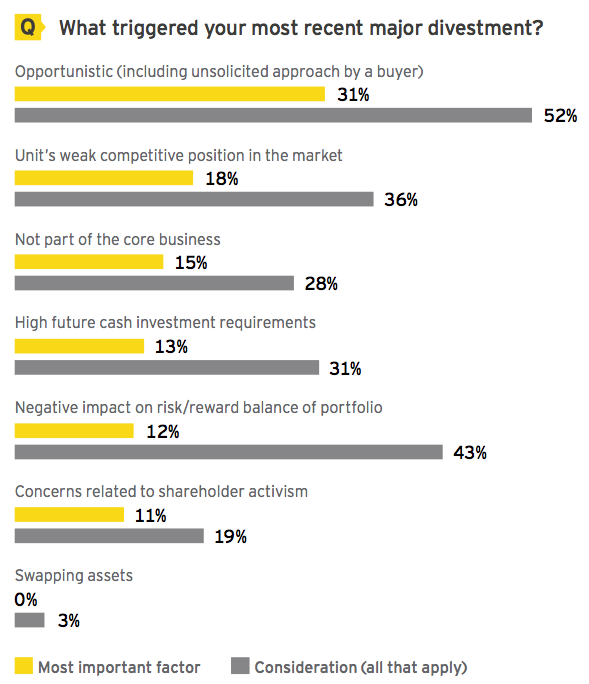

Yet despite the anticipated growth in divestment activity, many companies continue to take a tactical approach to their transactions: 52% say their last divestment was opportunistic, and the greatest portion (46%) say their next asset sale, if any, will likely be opportunistic as well. This is a major shift from previous editions of the Global Corporate Divestment Study that saw companies making divestments more strategically — proactively selling assets, often strong ones, that were no longer core to their business.

A successful divestment meets three criteria:

- Has a positive impact on the valuation multiple of the remaining company

- Generates a sale price above expectations

- Closes ahead of timing expectations

Only 19% of sellers in our survey meet all three key success criteria. What sets these high performers apart? They take the time to prepare well in advance of a divestment, they understand the potential buyer pool and the buyers’ needs, and they communicate the value of the transaction to internal and external stakeholders.

Even as corporates are taking a more opportunistic approach to divestment in this more-active M&A market, the vast majority are satisfied that making the divestment in the first place was the right move. Among companies that completed a divestment, 84% said they believe it created long-term value in the remaining business. But there is room for improvement — our survey also reveals that these divestments may not have met the full range of success criteria (see box above), indicating there is still value to be captured.

Why the private equity perspective on exits is important

Our survey is based on interviews with both corporate and PE executives. The corporate responses we received suggest there is much companies can learn from expert buyers and sellers — private equity firms — regardless of whether they consider PE a likely buyer of their business.

Over the past three years, PE firms have exited companies at nearly 1.5 times the rate at which they’ve acquired them; in fact, the 20 largest PE firms have each sold an average of eight companies per year. Moreover, they are very good at what they do:

- Over a 10-year period, USPE firms outperformed public markets by 62%.

- Only 1% of PE firms that responded to our study say their last exit did not meet timing expectations.

This section focuses exclusively on the overall divestment rationale and performance of our roughly 900 corporate respondents. And the next two chapters focus specifically on what portfolio-review and divestment-execution lessons companies can learn from PE in order to improve overall transaction success.

Corporations have clearly bought into the idea of selling, yet their results to date have been mixed. Given the high expectations corporates have for their divestment activity over the next couple of years, we strongly recommend that future corporate sellers look to the PE buy- and sell-side perspectives to improve their divestment processes.

In depth

Market data shows positive effect of corporate divestments

Nearly a decade of deal-market data tells us a great deal about divesting — both its potential and its limitations. Based on market data from nearly 800 deals globally since 2006, we have found that strong companies use strategic divestments to improve earnings and increase shareholder value at a greater pace than the market. Moreover, larger divestments seem to have a greater positive impact on the remaining company post-sale. However, for underperforming companies, while divestments often improve their value relative to the market, a divestment on its own does not tend to fix systemic weaknesses, especially in companies that are not performing in line with peers.

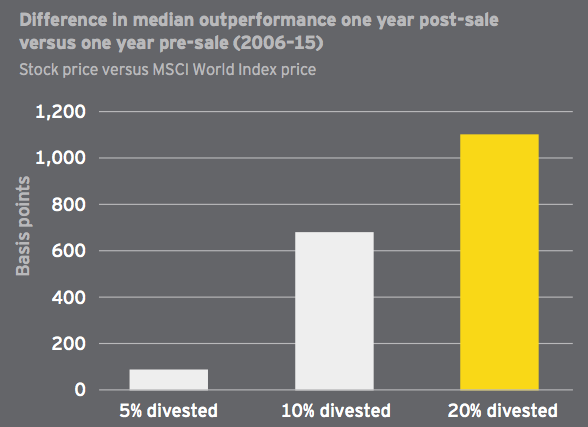

The market likes a big deal

Investors tend to reward companies for transformational divestments. For strong companies — those that outperform their respective index — generally, the more transformational the divestment, the greater their stock price outperforms the index in the year following the sale (comparing post-close performance versus the year before). For example, since 2006, companies that divested 5% of their business outperformed by 91 basis points more in the year post-divestment. However, companies that divested 20% of their business increased their outperformance by 1,104 basis points during the same time period.

These figures may even understate the case. In the above measurement, the one-year performance period pre-sale includes a period of roughly three to six months between when a company announces a deal and when it closes. During this period, the company’s stock price will already begin to reflect the market’s perception of the potential transaction, and some of the increased value may already be recognized pre-close. This fact only enhances the potential effect of divestment: it implies that outperformance versus the benchmark could be even greater than what is reflected in the post-close performance.

Recent deal trends — the effect of divesting 10% of a company

We have also seen a number of trends recently among more sizable deals — companies that divested at least 10% of their total enterprise value within the last five years.

Stock price performance

Strong companies tend to outperform the public index at an even greater rate once they divest. These companies outperformed the public index by 612 basis points more than they did in the one-year period pre-sale. Similarly, while a divestment is not a quick fix, even underperforming companies were able to get 235 basis points closer to their benchmark’s growth rate.

Effect on EBITDA multiple

Strong companies are able to unlock shareholder value with their divestments. The median growth rate of their EBITDA multiple one year after their divestment was 24.3%, compared to 6.1% for underperformers. In sum, while there is a large dispersion between outperformers and underperformers, on average, companies generally experience a positive effect on their EBITDA multiple post-sale. This is the effect of increased investor confidence in the remaining company that stems from an increased focus on the core business and improved growth prospects.

Effect on revenue growth

For strong-performing companies, divesting generally has — perhaps ironically — a positive effect on revenue growth. The median revenue growth for outperforming companies the year after their divestment was 4.5% (versus -0.9% the year before the sale); for underperformers, the increase the first year after sale was 0.8% (versus -1.8% the year before). This revenue growth is likely the result of companies shedding slower-growth or underperforming businesses and using divestment proceeds more aggressively to grow their core business or pursue new markets.

What can corporates do to improve divestment performance?

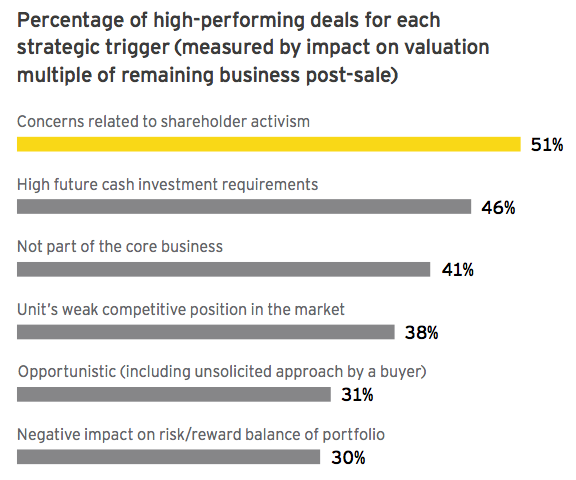

Don’t wait for a buyer — make a move before you’re forced to act

The increased popularity of opportunistic divestments is likely the result of the more active M&A marketplace, filled with a myriad of eager and proactive buyers, as well as the opportunity this deal market provides companies to raise fast cash. However, our research shows that opportunistic divestments are among the least likely to positively affect the remaining company’s valuation multiple post-sale. Among respondents who achieved a high-performing deal, those triggered by opportunism make up one of the smallest proportions, whereas those triggered by shareholder activism concerns or future cash requirements include much larger percentages of the high performers (51% and 46%, respectively).

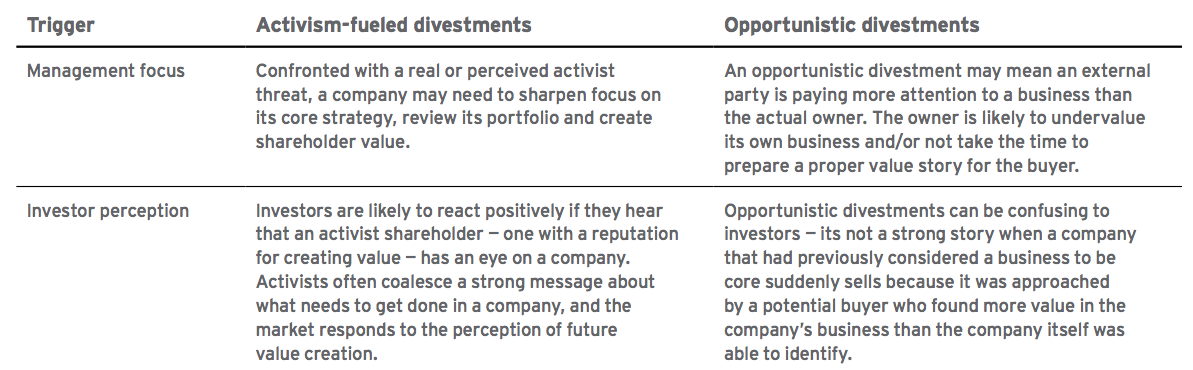

There are numerous potential reasons for such varying success between divestments driven by shareholder activist concerns and opportunistic divestments:

Companies are much more likely to improve the value of a business over the long term if their divestment decisions are consistent with their announced strategy. In other words, they should think like an activist before there is any concern about being forced into action.

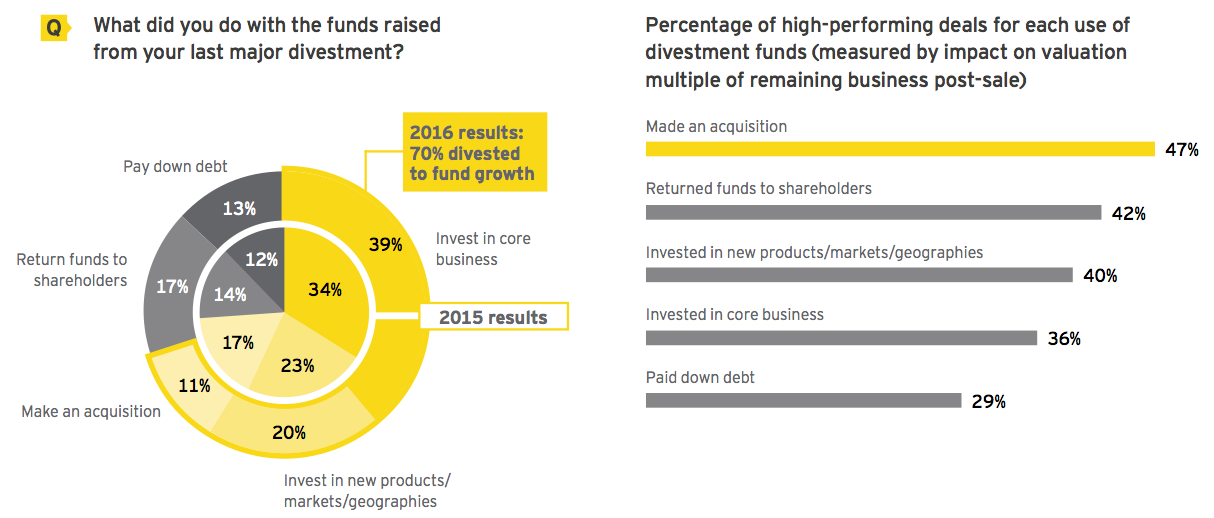

Use divestment proceeds for an acquisition

A key to divesting successfully is not only to plan for the sale, but also to consider how to use the proceeds. Seventy percent of our respondents used the funds from their previous divestment to grow their core business, through investing in new products/markets/geographies or acquiring a complementary business.

On the whole, compared with last year, companies are more focused on investing in organic growth and less on using divestment funds for an acquisition or pursuing new markets. For example, compared with last year, 35% fewer companies are planning to make an acquisition with divestment proceeds (11% versus 17%). Those who did use their previous divestment to fund an acquisition were 62% more likely to have experienced a higher-than-expected valuation multiple on the remaining business post- sale than a company that used the funds to pay down debt (47% versus 29%).

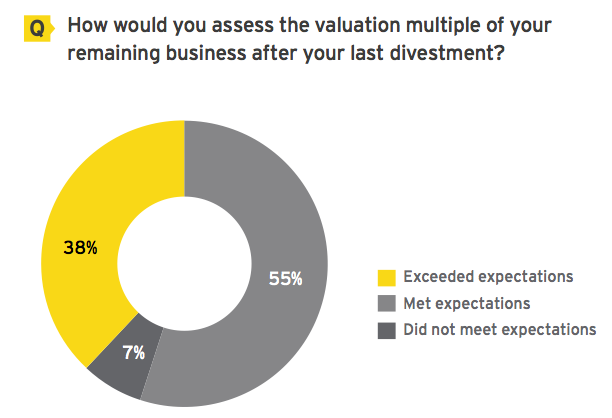

Prove divestment value to your investors

In order to have a positive effect on valuation multiple, it’s not enough to achieve a good sale price and close the deal on schedule. Sellers must communicate the deal’s alignment with future strategic direction — why they are divesting, how they define their core business and how they will use divestment proceeds. In our survey, just over one-third of companies succeed in this regard: 38% said their most recent divestment exceeded expectations in terms of its effect on the valuation multiple of the remaining business. More than half (55%) said their divestments were in line with expectations.

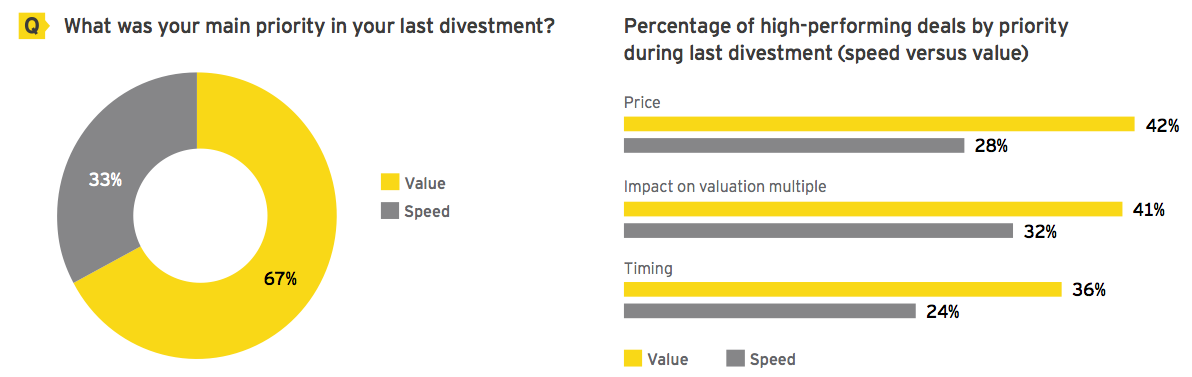

Less need for speed: big change over last year

Two-thirds of companies now place greater emphasis on value rather than speed. This is another significant shift from last year’s divestment study, which found a 50/50 split between speed and value. This change reflects the focus on overall shareholder value. And sellers know that strong availability of capital means greater competition for good assets and potentially higher bid prices.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, companies that prioritized value were more successful at all three divestment success criteria: price, speed and valuation multiple post-sale. The likely reason for this much stronger performance is that companies prioritizing value are often well-prepared for the separation process and buyer communications. However, those that prioritize speed often take shortcuts with buyer information and operational separation planning, which ends up lengthening the process and eroding value.

Consider all potential buyers

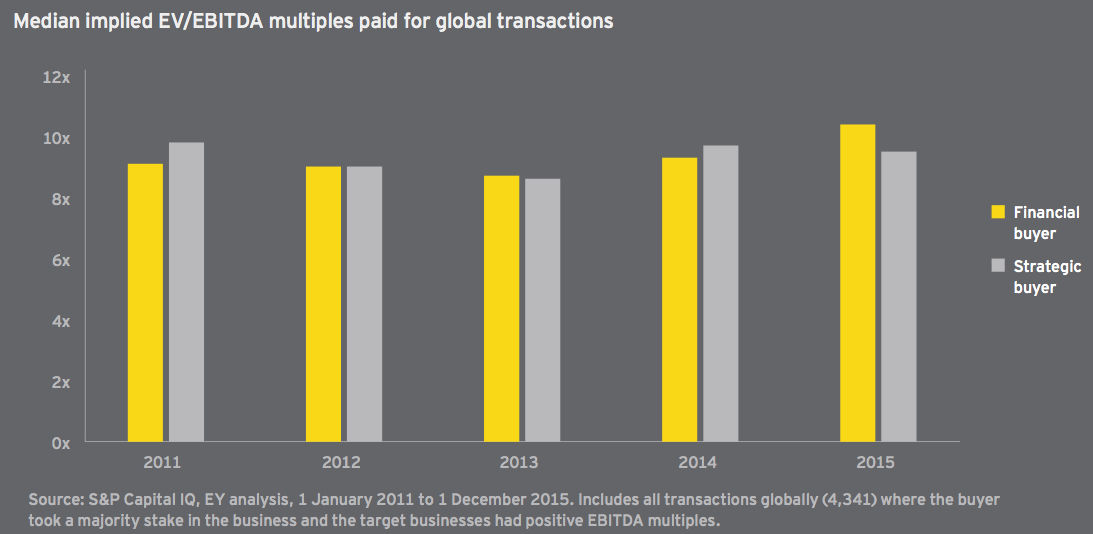

Only 11% of executives surveyed sold to private equity buyers in their most recent major divestment. One key reason is that sellers think strategic buyers will pay a higher multiple. But that isn’t necessarily the case. Private equity buyers are often more creative in their evaluation of potential acquisitions. Corporate buyers, by contrast, are often unwilling to pay for synergies. Market data shows that strategic and financial buyers pay similar multiples for businesses, and there is no clear pattern of one buyer type consistently paying more than another.

2. Portfolio review: think frequent and flexible

Most companies believe they run effective portfolio reviews, but they are often slow to pivot as market conditions change. The value of non-core businesses under a corporate umbrella can erode when there is no divestment imperative. In extreme cases, inaction can leave companies vulnerable to shareholder activism or hostile bids.

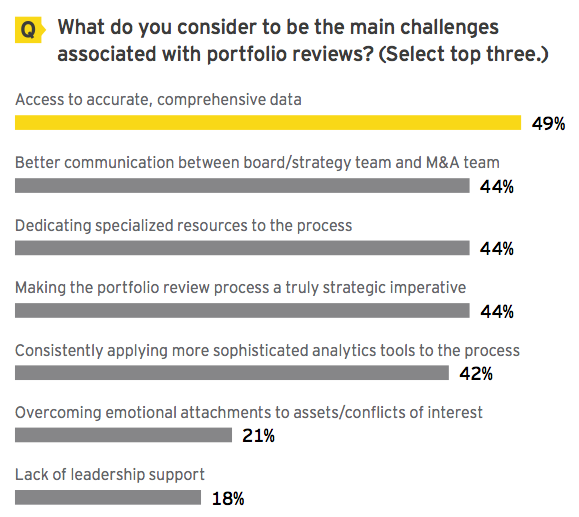

In our survey, 56% of corporate respondents say shortcomings in the portfolio review process resulted in failure to achieve intended divestment targets. There are many challenges — not least getting access to accurate, comprehensive data, and communication shortcomings between the board or strategy team and the M&A team. And nearly half of companies (44%) say one of their most significant challenges is making the portfolio review a strategic imperative.

PE owners, on the other hand, tend to place their investee businesses under constant review, such that they can use their influence to change strategic direction quickly. PE firms also use aggressive industry benchmarks and advanced analytics to assess capital performance. This means they are acutely aware of when and how to grow, fix or exit a business, and they largely avoid crisis management and fire sales.

53% say they have held on to assets too long when they should have divested them

Lessons learned from private equity

Frequency: make reviews a habit, not an event

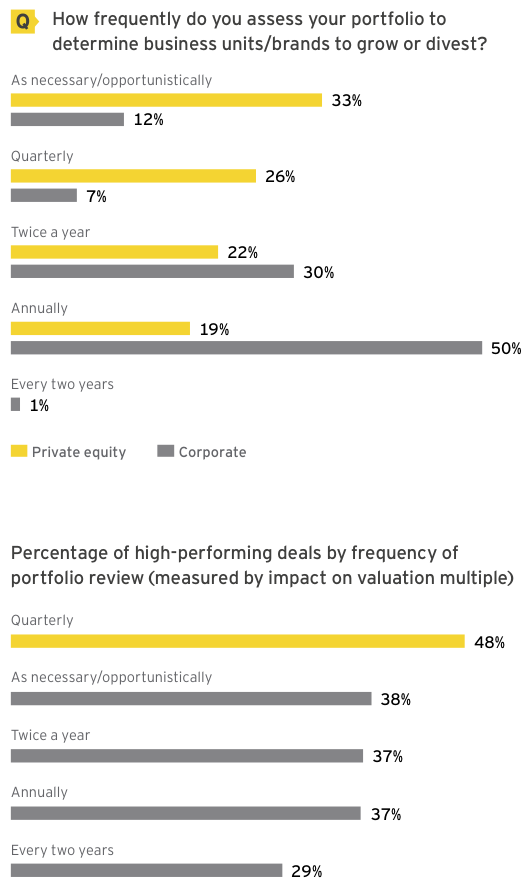

Private equity firms make portfolio reviews an ongoing activity, more so than their corporate peers. For example, more than one-quarter of PE firms carry out portfolio reviews quarterly, compared with just 7% of corporates; in all, nearly half of PE firms conduct reviews at least twice a year as a matter of course.

This PE approach should serve as a model for all enterprises, particularly as the digital revolution, big data and activist investors are impacting everyone’s business model and forcing companies to review performance more often. Specifically, we believe corporates should carry out three key types of reviews:

• In-depth portfolio review. These reviews should be conducted once or twice a year.

• Quarterly performance review. Every quarter, public companies should understand in detail performance against plan, macro market dynamics and competitor actions, and accordingly, whether any changes are required to their capital allocation and structure.

• Use analytics for real-time insight. Companies should use internal and external analytics to stay closer to their businesses and ideally have real-time access to meaningful granular performance data in order to make faster and more precise decisions.

Our survey shows a clear link between frequent portfolio reviews and divestment success. Among the respondents who experienced high-performing deals, 48% carried out reviews quarterly and 37% annually — a 30% difference in likelihood of success.

There are other implications of infrequent portfolio reviews. Shareholder activists tend to get involved when the market perceives that a company does not appreciate the inherent value in its portfolio of businesses and is slow to act. This is becoming a widespread problem: 78% of executives expect the same or an increased number of unsolicited or hostile bids within the next year.

Shareholder activism in the US

• The number of activist campaigns increased by 17% between 2010 and 2014 — and 2015 is set to outpace 2014 (annualized 644 campaigns in 2015 versus 518 in 2014).

• Divestments are the second most frequent change activists are pushing, behind governance — which can also result in a divestment.

• Technology, consumer products and retail, and life sciences have been the most targeted sectors over the last five years (455,322 and 265, respectively).

Data: good decisions don’t come from bad information

Nearly half of corporate executives say access to accurate, comprehensive data is a significant portfolio review challenge. Businesses are often burdened with unclear cost allocations, onerous intracompany pricing policies and lack of dedicated balance sheet responsibility. This makes a business’s contribution to the portfolio, as well as potential stand-alone performance, difficult to determine.

Below are suggestions to help better understand portfolio performance and create a better value story for a buyer.

• Produce more granular data. PE firms empower their information systems to provide a deeper dive into business unit financials. The costs of this effort are not inconsequential but should be recouped through incremental shareholder value over the long term

• Set benchmarks like an outsider. Align the key performance indicators used for portfolio reviews with those that are typically looked at by external investors

• Stress-test the data. Empower a portfolio management team comprising people from different functional areas to make sure the data is accurate and supportable

• Understand business complexity. Consider the extent to which each business unit is integrated with the remaining company (e.g., overlap in customers, vendors, facilities, shared services)

Data causes divestment dilemmas

• 81% say poor-quality data makes it difficult to use analytics effectively.

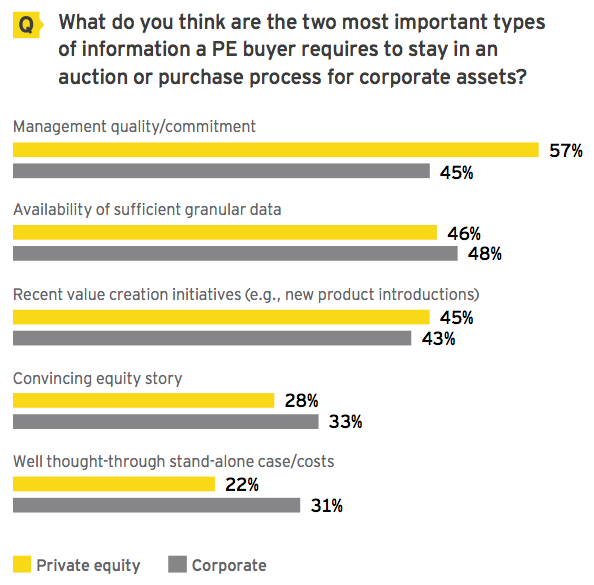

• 46% of PE buyers say availability of sufficient granular data is the most important factor in staying in an acquisition process (e.g., gross margin, cost of sales, working capital).

• Conversely, 44% of PE buyers say lack of confidence in information is the most significant factor that causes a PE firm to reduce its offer price or walk away from a deal.

Analytics: critical for performance measurement

The use of analytics isn’t just about tools. It’s about taking advantage of a proliferation of data that is now accessible both to a company and its outside influencers. The last thing companies want is for a third party (e.g., a shareholder activist, a potential buyer) to uncover something about the company that its leadership didn’t know because they hadn’t fully considered all potential sources of available data.

Companies need to make sure their analytics provide answers to critical questions like these:

• What are the true drivers of historical and forecast performance (financial and nonfinancial)?

• What are probable future outcomes for the portfolio under various assumptions, and how could this affect a deal as well as the remaining organization?

• What strategic options offer the most value-creation potential?

• What are the risk and return characteristics of each business in the portfolio, and what is the overall effect of their relationships and interdependencies?

42% of executives say they need to apply more sophisticated analytical tools to their process

Priority analytics capabilities are not areas of strength

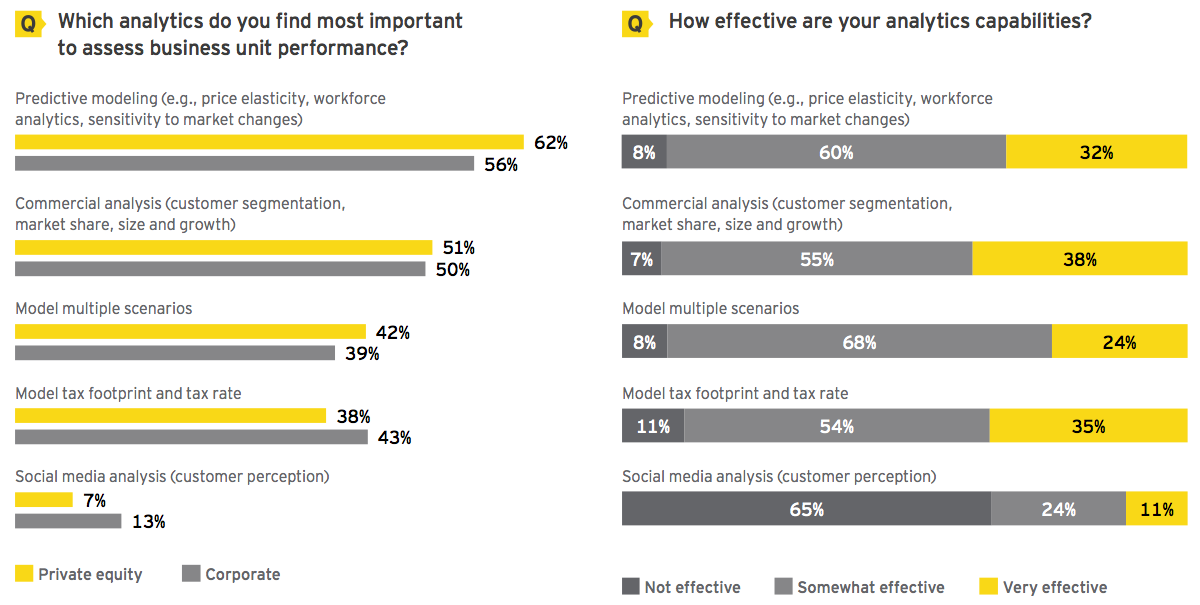

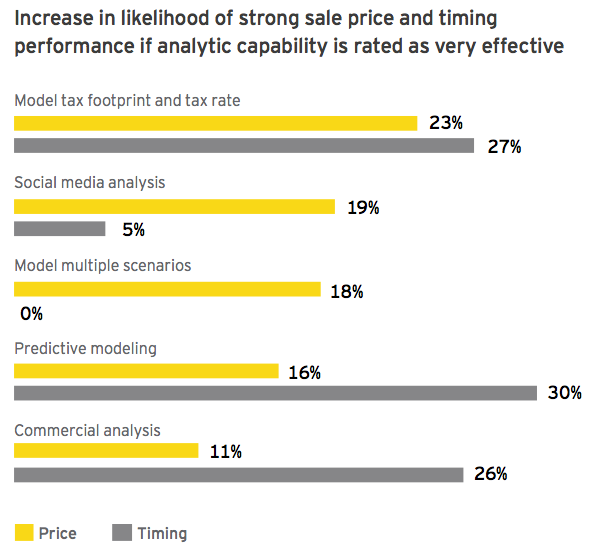

Sixty-two percent of PE executives say that they find predictive modeling most important to assess business performance, compared with 56% of corporates. PE firms are also slightly more likely to use commercial analysis and to model multiple scenarios. While corporates are placing increasing importance on analytics, few believe they have advanced analytics capabilities.

Companies that do rate their abilities as very effective are more likely to carry out divestments that exceed expectations, likely because robust forecasts support the equity story, and therefore the diligence process.

The potential buyer of a manufacturing company asked for 20 years of insurance claims data. The buyer wanted the data to use as a basis to predict future costs. The seller had the data but had never analyzed it before, so they hadn’t considered how it would affect the bidder’s view of the business.

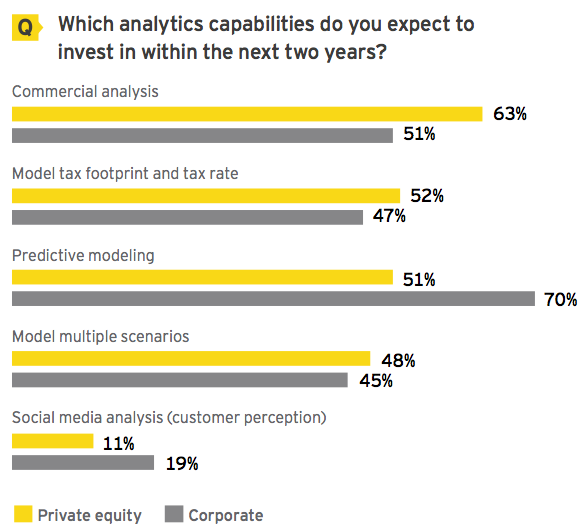

Companies plan to invest in the highest-impact analytics

To their credit, many companies recognize this structural weakness and are planning to address it. Successful companies are increasingly seeing the benefits of using predictive analytics to provide early visibility to the expected performance of each business, as well as greater insight into the expected value of a sale, including associated synergies. A greater percentage of PE firms expect to ramp up their commercial analysis capabilities (63%) than their corporate counterparts. These capabilities could help companies better understand their competitive positioning and customer trends to better inform valuation and transaction decisions. Predictive analytics, commercial analysis and scenario modeling can also help executives identify what attributes of a deal might attract a broader group of owners willing to pay more for an asset, and when and why they would be willing to pay more.

Social media is being overlooked

Every day, more than 500 million opinions, comments and suggestions are posted on Twitter, with countless more appearing on reviews, blogs and other online forums. These real-time, unfiltered opinions contain a treasure trove of intelligence that can help companies track market trends and extract insight for portfolio reviews.

For example, social media analysis helps executives understand sentiment changes about a division, product or service and benchmark them against various business units, specific competitors or entire industries. In addition to traditional metrics, these findings can serve as indicators of future business prospects. Social media analytics can even help companies understand investor opinions if the company becomes an activist shareholder target.

Many companies are already leveraging social media analytics for product development. Ideally, these analyses should expand beyond individual business units and into wholesale portfolio reviews, which will help companies compare potential growth across business units and help inform decisions on whether to invest in a business or sell it.

In depth

Communication: poor information-sharing hinders divestment success

Improving communication between the board/strategy team and M&A team

Forty-four percent of executives say they need better communication between the board or strategy team and the M&A team. Here are some leading practices to improve the dialogue:

• Establish portfolio review protocols so that it is clear which businesses are on a watch list

• Develop appropriate models, timelines and milestones relative to pending transactions to allow time for value enhancement

• Develop related stakeholder communications, including communiqués directed to equity analysts

• Align internal functional work streams and service providers

Appoint a project leader to manage the portfolio review process

Forty-four percent of corporate executives say dedicating specialized resources to the process is a significant portfolio review challenge, and nearly one in five companies (18%) say they lack leadership support. A key way to resolve these issues is to enlist a project leader who is sufficiently senior and experienced in the organization to have the C-suite’s ear. This person is empowered to secure the smartest functional leads — colleagues who aren’t always readily available — and to make them accountable.

No external advisor can do that.

Managing internal conflicts of interest

One in five companies (21%) says that overcoming emotional attachments to assets or other conflicts of interest is a significant portfolio review challenge. Here, we outline some key ways to overcome it.

During the portfolio review process:

• Define objective evaluation criteria

• Discuss portfolio review findings regularly in board meetings to support objective decision-making

• Involve the business stakeholders in the process so that they understand performance expectations, and the review feels less like an event — or a threat

Once the decision has been made to divest:

• Listen to employee concerns early and explain the vision for the separated business

• Involve business stakeholders in discussions with external advisors so they understand potential opportunities, both for the parent company and for the target

• Incentivize key executives to effectuate a successful transaction (e.g., retention payments, stock options, performance bonuses)

A company publicly announced the timing of a spin-off without alignment among the deal team. During the separation, the company discovered several regulatory hurdles in numerous countries that delayed the transaction by six months. The stock lost more than 20% of its value post-announcement and did not recoup its losses until after separation.

Deal execution: fail to prepare, prepare to fail

With boards under constant scrutiny to build shareholder value, sellers of corporate assets need to answer three critical questions: What drives the business’s purchase and valuation decisions? How can the seller develop a value story tailored to individual bidders in order to maximize value? What impact will the divestment have on the remaining business?

Sellers who can answer these questions make an asset easy to buy and create competitive tension. The value story should clearly articulate the future value of the separated business, which often deviates from the current operating model under the current corporate umbrella.

And yet, just over one-third (36%) of companies have developed consistent execution procedures across their divestments. Corporates continue to point to deal execution as a divestment area ripe for improvement.

Lessons learned from private equity

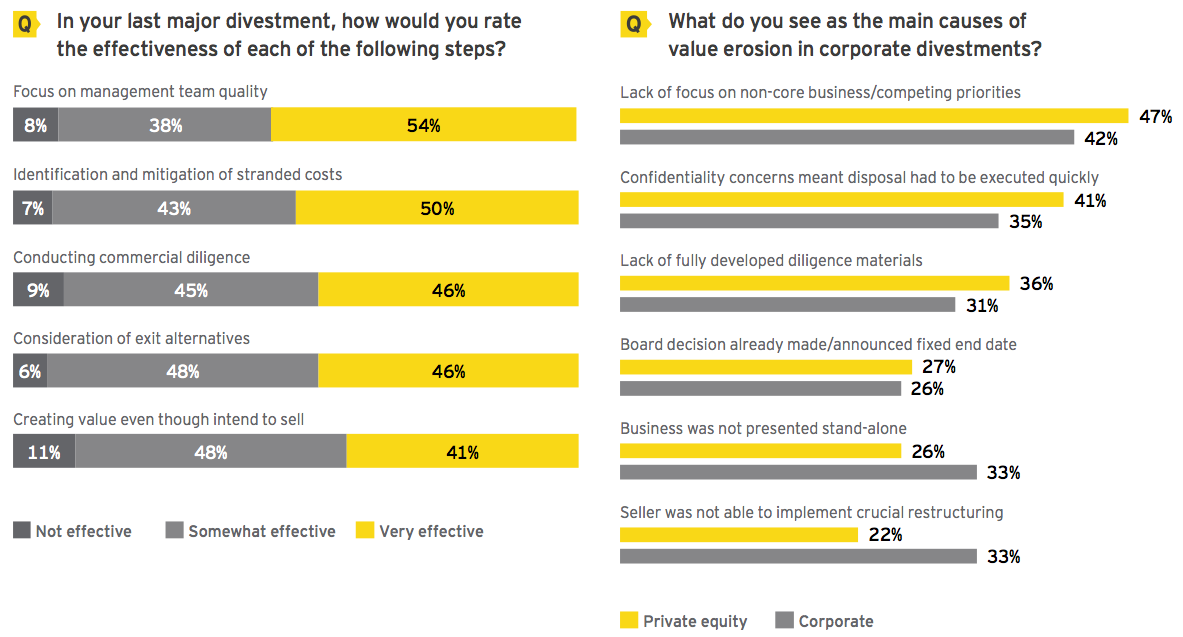

It’s still your business: don’t ignore it until it’s off your books

Only 41% say they are very good at continuing to create value in businesses they intend to sell, an area where PE excels. Corporate and PE executives agree that most companies sacrifice value due to pressure to allocate time and resources to their core businesses (42% and 47%, respectively).

This short-sightedness is challenging to deal execution results. Our research shows that those who continue to create value in a business targeted for divestment are 75% more likely to receive a higher-than-expected price and 59% more likely

to experience a higher-than-expected valuation multiple post-sale. Sellers must therefore continually evaluate the potential returns from continuing to optimize the business’s attractiveness to buyers.

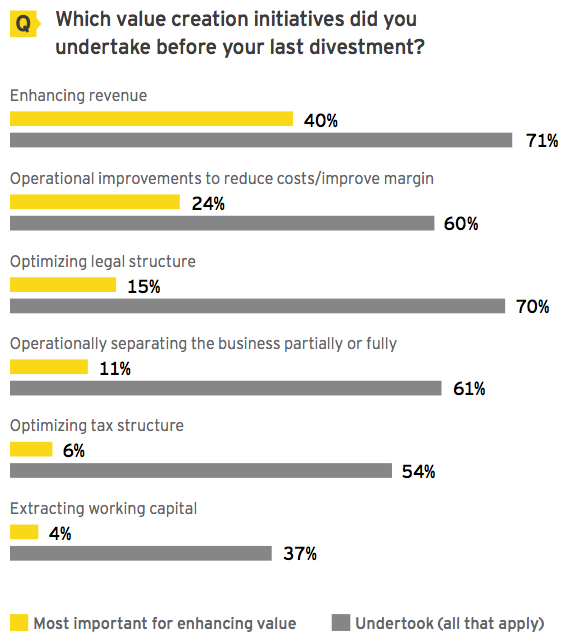

Operational separation: vital to value creation, often neglected

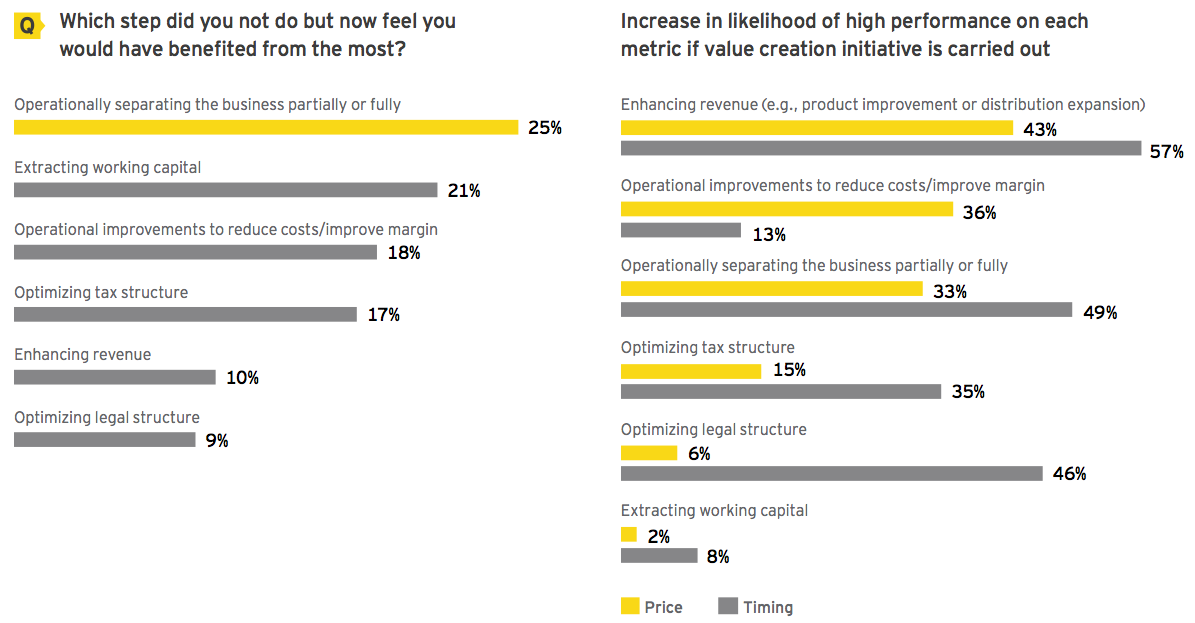

One of the most effective ways to create value pre-sale is to present a compelling vision to a potential buyer of how the business will be operationally separated and how it would fit into the buyer’s organization. This initiative comes up most frequently when corporates are asked about the step they did not undertake on their most recent divestment, but wish they had.

Sellers should be able to ensure that:

• Stand-alone financials can withstand diligence

• Assets, liabilities and operations within the perimeter of the deal have been vetted

• Separation activities, particularly long lead-time items, have already commenced. Sellers are often reluctant to implement these measures until a buyer has been identified and appropriate personnel are cleared because they can generate significant work and cost. But waiting for buyer agreement can cause delays and increase transaction execution risk. Ideally, a seller will begin separation as part of its preparation process — developing a clear view of what is included in the deal and preparing a detailed separation road map. This plan details timelines, costs and transition arrangements, which enhances buyer confidence and adds certainty to negotiations.

Communicate synergies: take back the buyer’s upside

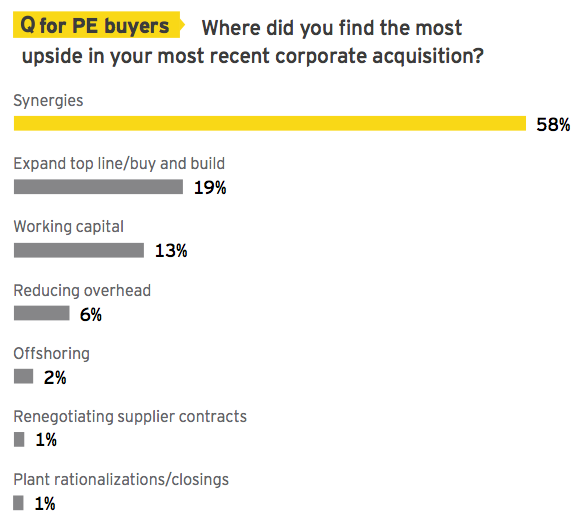

Most PE firms (58%) said synergies were the source of their greatest upside. This suggests that corporate sellers should be much more rigorous in how they identify, communicate and value potential synergies for each potential buyer.

It may also suggest that PE is good at building scale through acquiring platform companies and subsequently bolting on acquisitions. In essence, they are finding synergies and are thereby able to create an efficient cost base and a more efficient organization overall.

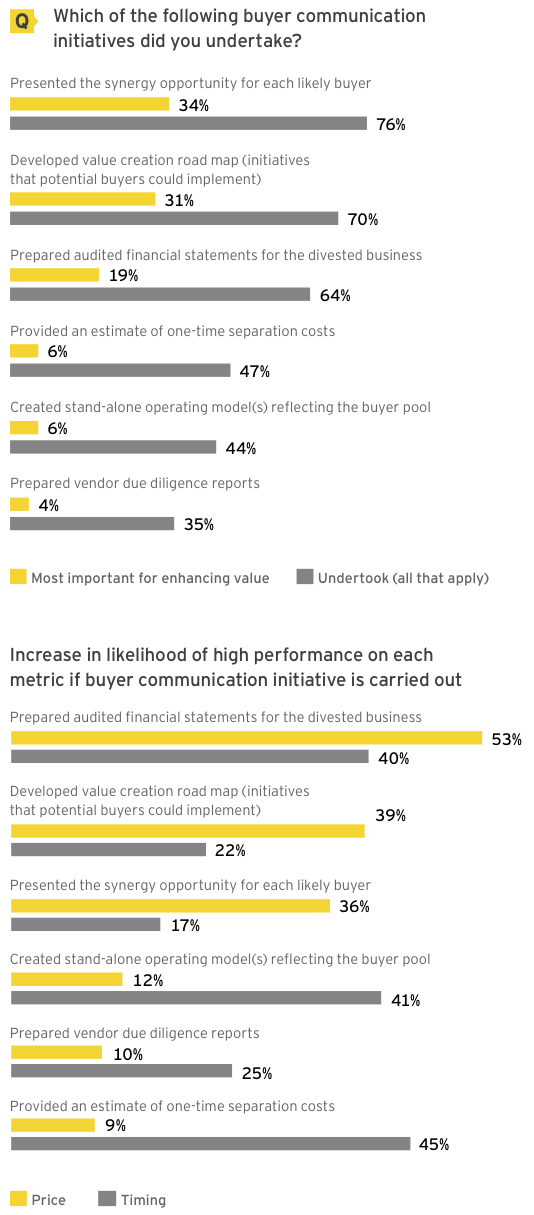

Similarly, presenting each likely bidder with its own tailored synergy opportunity was found to have a significant impact on overall success.

A potential buyer was very focused on understanding stand-alone costs. The seller refocused the conversation on market, functional and country overlap. Leadership convened staff across functions to crunch numbers and determine the value the buyer could extract relative to synergies. The seller ultimately identified US$32 million in synergies, representing US$208 million in value based on the sale’s 6.5x multiple.

Keep a buyer in it to win it: management quality and commitment

PE firms say management quality and commitment are the factors they prioritize most when deciding to stay in an auction process. If a PE firm does not have confidence in who will run the business and deliver on plan, they will seek out their own team.

Corporates, like PE, should give sufficient focus to the management factor while also keeping in mind that, at some point in the sales process, management loyalty will shift from the current owner to the potential new owner. Therefore, sellers should establish rules and incentives to keep demarcation lines clear until a sale is concluded.

PE firms seeking add-on acquisitions and strategic buyers might use the existing business’s management or choose which management team they prefer. Regardless of a buyer’s intentions regarding current management, a business with a strong management team is much more likely to be run well and use strong data for both its decision-making and the sale process.

Provide the right details: keep buyer’s needs in mind

PE buyers, in particular, have an eye for detail. But sellers should be able to provide the following to any smart buyer:

• Explanations of margin development and cost pass-through, including detailed value creation bridges and a clear view to the forecast

• Clarification if the business will be stand-alone,and sufficient details regarding stand-alone consequences

• Links between performance of the business and the markets in which it operates

• Future plans and opportunities for the business, including additional upside potential that is not reflected in the current-state business

On a recent complex carve-out transaction, a seller circulated 20 targeted-buyer presentations, but the information did not explain clearly what was actually included in the deal.

The result: more than 70% of the potential buyers declined, and the remaining six dropped out early in the diligence process. One potential buyer said, “Far too much time would be required of us to purchase this business.”

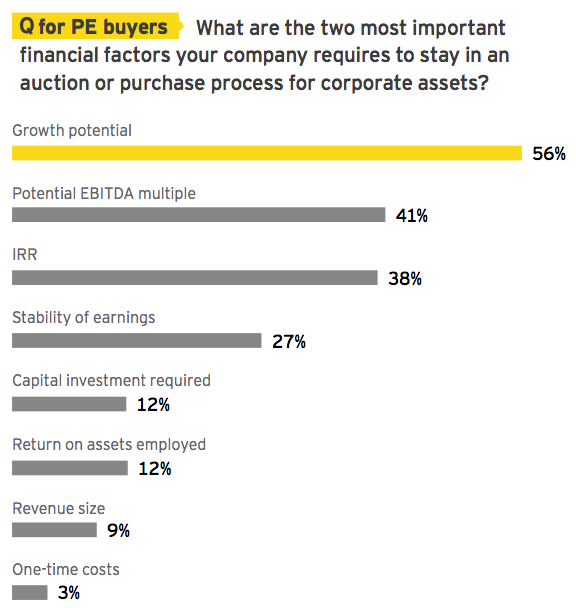

Most important financial factors for buyers

More than half of PE respondents (56%) say growth potential is the financial factor they most prioritize, followed by potential EBITDA multiple and internal rate of return (IRR). It is therefore incumbent upon sellers to employ data analytics (e.g., social media, predictive analytics) as well as traditional commercial diligence to help buyers understand the growth potential. As for EBITDA, value creation bridges are critical to helping buyers identify efforts that can be undertaken to drive value post-close (and therefore the EBITDA multiple they are willing to pay).

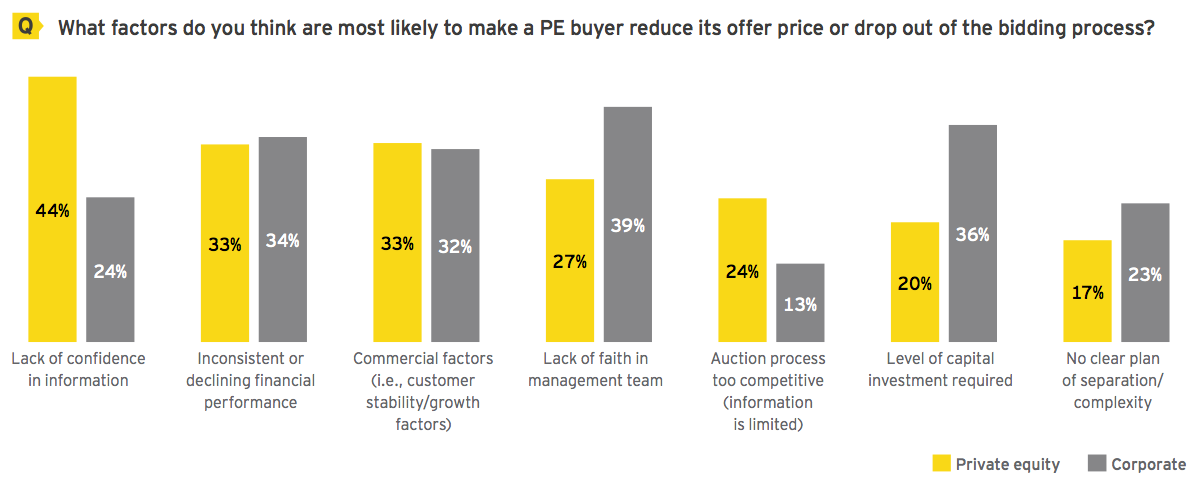

What makes a buyer walk away from a deal

Companies should understand how to create a compelling story for experienced buyers. Particularly among PE buyers, there is often a stark difference between what sellers think causes a reduction in offer price or a bidder dropout and what PE firms say actually drives them away.

Corporates think that lack of confidence in the management team and level of capital investment required are the most likely factors. For PE respondents, the management team is indeed important, but so too are inconsistent or declining financial performance and commercial factors.

We draw two major conclusions from these responses:

• Corporate executives may need to focus on different priorities. Early in the process, PE wants strong management in place. But while this will make them interested in the asset, PE buyers also want confidence in the financials. This means sellers must gather sufficiently granular data to support the equity story

• Sellers must provide credible information to buyers. Nearly two-thirds of corporate executives say they prepare audited financials — and yet, lack of faith in information is the leading cause of PE buyers discounting a deal. Any potential buyer needs to understand the deal-basis financials (e.g., how the company is being run, how it has performed, what cash flow looks like on a pro forma basis)

Conclusion

Looking forward: since you’re likely to divest

Nearly half of companies plan to divest in the next two years, and another 46% are open to the possibility. For example, life sciences companies often divest to fund new opportunities, financial services companies continue to react to regulatory changes, consumer products companies are better at predicting or reacting to customer preferences, and technology companies are keeping pace with fast innovation and activist shareholders.

Unless you’re part of the 5% that does not plan to divest over the next two years, now might be the ideal time to start considering if you have the right infrastructure and teams in place to decide what, when and how to divest.

Evidence from this study clearly shows that companies that divest strategically — including preparing assets for sale and carefully considering how to use sale proceeds — are much more likely to execute divestments that positively affect their remaining business over the long term. Private equity firms have proven to be successful buyers and sellers. They are not the end-all, but they transact more often than corporates and their 10-year performance is impressive.

With limited resources and time, companies should re-examine which practices are shown here to have the greatest correlation with success, and which aspects of the value story are most important to discerning buyers.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter