Publications Emerging Markets Review: Rights Issues And Creeping Acquisitions In India

- Publications

Emerging Markets Review: Rights Issues And Creeping Acquisitions In India

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Gaurav Jetley, Shamim S. Mondal

Abstract

We analyze the extent to which promoters of firms listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange are using rights issues to circumvent regulatory provisions related to creeping acquisitions. We find that promoters use rights issues that do not have specific objectives for purposes of realizing an increase in their shareholdings. We find that a rights issue often follows a year in which the promoter has realized a loss of shareholdings. The results are especially true for firms belonging to a business group.

1. Introduction

Creeping acquisitions refer to the purchase of company shares by its investors (usually, promoters or shareholders with significant holdings) over a number of small transactions, so as to increase the investors’ stake in the company by an economically significant amount without requiring any disclosure or other action by the investors. Thus, creeping acquisitions allow promoters (principal owners) to increase their stakes in firms by up to the maximum amount allowed under the prevailing securities regulations without triggering the need for any action mandated by the regulators.

In this paper, we analyze the extent to which promoters of firms listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange (“BSE”) may be using rights issues to increase their stakes in firms, circumventing regulatory provisions regarding creeping acquisitions in the process. We find strong evidence that promoters of Indian firms could be using rights issues as a mechanism for increasing their stakes, and this is particularly true for firms belonging to Indian business groups, which are a collection of publicly traded firms spread across industries with significant common ownership and control, usually by a single family (Khanna and Palepu, 2000). Increases in stakes similar to the ones observed related to rights issues would otherwise have triggered disclosure and open offers per the regulatory norms.

The Indian securities markets are primarily regulated by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”), established in 1992 to “protect the interests of investors in securities and to promote the development of, and to regulate, the securities market” (SEBI, n.d.). Over the years, SEBI has taken several steps to improve disclosures by firms and corporate governance. Prominent among these are formation of: the Malegam Committee in 1995 to review disclosure requirements for public and rights issues that resulted in the SEBI Disclosure and Investor Protection Guidelines, 2000 (“DIP guidelines”) (Malegam, 2004); the Bhagwati Committee in 1995 (and later, in 2001) to review regulations surrounding substantial acquisitions and takeovers that resulted in the Substantial Acquisitions of Shares and Takeovers Regulations (“Takeover Code”) in 1997; and the Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee (“KMBC”) in 1999 to identify steps to, among other aims, improve disclosures of financial and non-financial information to investors, and suggest a code of corporate governance practices that resulted in introduction of Clause 49 in the Listing Agreement of the Stock Exchanges in 2000.

SEBI’s primary motivations for enacting these regulations have been to improve protection of minority shareholders and improve corporate governance standards in the Indian financial market. For example, a key concern of the Takeover Code was to ensure that minority shareholders don’t lose profitable exit opportunities in the event of a change in control through privately negotiated acquisitions, particularly in a business environment of mergers and acquisitions involving foreign companies. SEBI’s focus on corporate governance is consistent with studies that have identified various benefits of improvement in corporate governance. For example, a cross-country study by La Porta et al. (2002) finds that firms in countries with better protection of minority shareholders and firms with higher cash-flow ownership by the controlling shareholder have relatively higher valuations. Further, better protection of outside shareholders is also associated with more valuable stock markets (La Porta et al., 1997), greater dividend payouts (La Porta et al., 2000), and higher correlation between investment opportunities and actual investments (Wurgler, 2000).

However, SEBI’s regulations related to rights issues seem to undercut SEBI’s regulations concerning creeping acquisitions. In particular, SEBI allows any change in promoters’ holdings caused by a rights issue not to count towards the creeping acquisition limit when computing the maximum amount by which promoters can increase their stake in the company in a year without triggering public announcement and open offer requirements. Thus, it is likely that promoters may use rights issues to increase their stake and thus circumvent rules related to creeping acquisitions. Such attempts to increase promoter shareholding through rights issue could be motivated by, among others, a desire to recoup a reduction in promoter shareholding in years leading up to the rights issue. We investigate this possibility in the paper.

We also document that the rights issues are being offered at a substantial discount (relative to prevailing market prices) to shareholders. In theory, the discount should provide an incentive to minority shareholders to participate in a rights issue in order to realize profits by subscribing to the issue, acquiring shares at a discount, and subsequently selling shares at the market price. We posit that market frictions such as taxes and transaction costs may be limiting investors’ ability to realize short-term gains associated with subscribing to a rights issue and then subsequently selling the rights shares.

We show that rights-issuing firms underperform similar non-rights-issuing companies. The underperformance is both statistically and economically significant. This is especially true for firms that undertake rights issues primarily to augment their working capital or retire debt (i.e., firms with non-specific objectives for the rights issues).

Our findings should concern policy makers like SEBI, because the ability of promoters to increase their stakes in firms, especially at prices below the market value of the stock of the rights-issuing company, is detrimental to the interests of minority shareholders, the very constituency that SEBI intends to protect. Increased promoter ownership concentrates more cash flow and voting rights in the hands of the promoters, potentially allowing them to make decisions that are disadvantageous to the minority shareholders. Increased promoter shareholding concentration through dilutive share issues has been defined as a form of tunneling by Johnson et al. (2000). In particular, Johnson et al. (2000) state that “the controlling shareholder can increase his share of the firm without transferring any assets through dilutive share issues, minority freeze outs, insider trading, creeping acquisitions, or other financial transactions that discriminate against minorities.” Furthermore, Bertrand et al. (2002) have shown that there is significant tunneling — transfer of resources by controlling shareholders across firms within a group — in firms belonging to business groups in India. The existence of tunneling is likely to exacerbate the adverse impact of increased promoter ownership on the interests of the minority shareholders.

To our knowledge, our paper is the first to explore the possible connection between rights issues and promoter shareholding. We provide evidence that promoters of Indian firms could be using rights issues as a mechanism to increase their shareholding, and that this might be related to gaining control. We demonstrate the underperformance of rights-issuing firms, and in particular the underperformance of firms that do not provide “specific” objectives in connection with the rights issues relative to a matched sample of similar firms. Our paper also explores the possibility that there are significant transaction costs involved in trading certain shares, which create barriers to fully exploiting pricing anomalies.

We make several contributions to the literature. Our paper is tied to Eckbo and Masulis (1992), who propose a theoretical model that frames the flotation method choice regarding how to issue additional equity based on the cost of issuance and expectations regarding shareholder take-up of the rights issue — i.e., the extent to which existing shareholders participate in the rights issue. We also contribute to the literature that examines how firms choose to raise equity, for example, Bøhren et al. (1997), Wu (2004), and Cronqvist and Nilsson (2005).

We extend the literature that studies rights issues. Among the papers that study rights issues in other contexts, Marisetty et al. (2008) find evidence that price reaction to a rights issue is significantly negative for group-affiliated firms compared to stand-alone firms, and Marisetty and Subrahmanyam (2010) find evidence of greater underpricing of IPOs of Indian group-affiliated firms. By examining the extent to which group affiliation could play a role in a firm’s decision to issue equity via a rights issue, we contribute to the literature on group affiliations of firms and its impact on corporate governance (and consequently, minority shareholders), firm performance and firm value. Khanna and Palepu (2000) report that affiliates of diversified business groups outperform stand-alone firms in the same industry.

Finally, we contribute to the discussion on how interests of minority shareholders may be compromised in India as a consequence of loopholes in regulations. Taken as a whole, our paper contributes towards a better understanding of the interplay of institutional features and ownership characteristics of firms in emerging markets that may aid in policy formations regarding corporate governance issues.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The next section provides details of the SEBI regulations that govern rights issues and creeping acquisitions. We discuss some salient features of Indian rights issues, as well as SEBI guidelines regarding rights issues and substantial acquisitions, and document how the frequency of rights issues by Indian firms have responded to variations in regulations regarding creeping acquisitions. In Section 3, we develop and present our hypotheses. Section 4 describes our data and empirical approach and discusses the results. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Overview of rights issues and creeping acquisitions

2.1. Characteristics of rights issues in India

A rights issue is a seasoned equity offering in which the issuing firm solicits investments from existing shareholders of a company via short-lived warrants issued on a pro rata basis (Eckbo and Masulis, 1992). A rights issue sold to existing shareholders could be with or without commitment from underwriters to purchase all unsubscribed shares. Alternatively, a company may issue additional equity via a firm commitment underwritten offer, in which equity is sold to investors in general; we will refer to these as seasoned equity offerings. Rights offerings are still relatively popular outside the US, and this popularity is linked to family control of public companies in Europe and East Asian countries (Cronqvist and Nilsson, 2005).

SEBI’s Handbook of Statistics on the Indian Securities Market 2008 shows that both the number of rights issues and the amount raised through rights issues have varied over time. SEBI has attributed the variance in issuance to, among others, increasing reliance on private placements, changes in economic conditions and changes in investor sentiment (SEBI, 1998). For example, in 1993, there were 370 rights issues by firms listed in India, raising Rs. 89 billion, but in 2002, there were only 12 rights issues that raised an aggregate of Rs. 4 billion, and in 2006, there were 39 rights issues raising Rs. 37 billion. The data on rights issues also show that the annual numbers are skewed by a few very large issues. For example, the number of rights issues in 2007 was 32, which is similar to the number for 2006. However, the amount raised in 2007 was Rs. 325 billion, which is over 8 times the amount raised in 2006. A review of the rights issues in 2006 and 2007 shows that in 2007 there were 3 issues that alone raised over Rs. 250 billion. In general, rights issues continue to be an important source of equity capital for Indian companies, and from 1993 through 2008 they accounted for about a third of the equity capital raised by firms.

The process of initiating a rights issue is fairly straightforward. Board approval is sufficient to initiate a rights issue, as long as the firm seeks to issue shares such that the total number of shares outstanding subsequent to the rights issue will not exceed the number of shares the firm is authorized to issue per its articles of association (i.e., charter). In addition, firms are required to notify the relevant stock exchanges about the decision to convene a board meeting for purposes of considering a rights issue, and firms are then also required to inform the relevant stock exchanges about the particulars of the rights issue soon after its board approves the offering. Changes in the authorized capital of a firm can be made via a general or special resolution, as mandated by a firm’s charter.

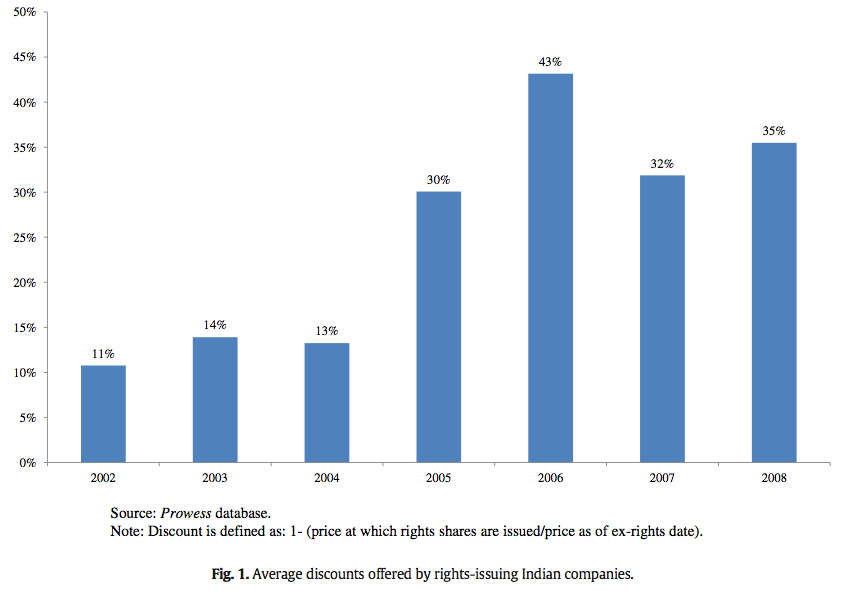

A few features of rights issues by Indian companies are noteworthy. In almost all cases, rights issues by Indian firms are not underwritten by investment banks, but are underwritten by the promoters themselves. That is, the promoters promise to subscribe to any shortfall in the uptake of the rights by the retail shareholders. Additionally, Indian rights issues are priced at a considerable discount to the prevailing market price of the issuing company’s shares, which contrasts with seasoned equity offerings in Europe and the US. For example, seasoned equity offerings between 1990 and 1998 in the US were priced at an average discount of 2.9% (Corwin, 2003), while the average discount on Indian rights issues is quite large, as we document below.

A few features of rights issues by Indian companies are noteworthy. In almost all cases, rights issues by Indian firms are not underwritten by investment banks, but are underwritten by the promoters themselves. That is, the promoters promise to subscribe to any shortfall in the uptake of the rights by the retail shareholders. Additionally, Indian rights issues are priced at a considerable discount to the prevailing market price of the issuing company’s shares, which contrasts with seasoned equity offerings in Europe and the US. For example, seasoned equity offerings between 1990 and 1998 in the US were priced at an average discount of 2.9% (Corwin, 2003), while the average discount on Indian rights issues is quite large, as we document below.

One explanation for the observed discount could be that the discount is offered to offset some of the costs that shareholders are likely to bear in order to participate in the rights offering. Hansen et al. (1986) identified taxes, transaction costs and liquidity costs as possible impediments to participation in a rights issue. Given that rights issues in India, in general, are underwritten by the promoters, a discount does serve as an incentive for minority shareholders to participate. Later in the paper we show that discounts are positively related to shareholder participation.

A review of articles in the Indian business press about rights issues suggests that firms may use rights issues as a way to reward shareholders. For example, a few articles state that one of the objectives of issuing firms is to reward shareholders with “robust” discounts. However, we do not find any strong evidence in our sample that supports the notion that rights issues are used to reward shareholders.

2.2. SEBI guidelines for rights issues

SEBI requires that firms seeking to issue equity via Initial Public Offerings or Further Public Offerings must meet certain profitability and/or capitalization thresholds. However, firms seeking to issue equity on a rights basis do not need to meet any such thresholds as per clause 2.4.1(iv) of the DIP guidelines. For instance, information provided on the SEBI website states that:

SEBI has laid down eligibility norms for entities accessing the primary market through public issues. There is no eligibility norm for a listed company making a rights issue as it is an offer made to the existing shareholders who are expected to know their company. There are no eligibility norms for a listed company making a preferential issue.

In addition to having no eligibility criteria, in 2009 SEBI removed certain disclosure requirements to make it easier and cheaper for firms to complete rights issues. Earlier, the disclosure requirements for rights issues were almost as exhaustive as for public issues. SEBI rationalized new disclosure requirements based on the assumption that “certain information about the entities [rights-issuing firms] that are listed and traded on the exchanges is available in the public domain for investors” (SEBI, 2009). Implicit in SEBI’s basis for reducing disclosure requirements is the assumption that high-quality disclosures are available to investors of listed companies, which may not be the case (Parekh, 2009). SEBI has also introduced changes that make it possible for firms to utilize funds available from rights issues faster. For example, revised section 8.19.1 in the DIP guidelines now allows firms to utilize the proceeds from the rights issue as soon as the basis of allotment is finalized.

One benefit of having no eligibility criteria is that there is no direct incentive for rights-issuing firms to manage earnings. For example, regulators in China have set specific thresholds for Return on Assets (ROA) that firms must satisfy to be eligible to issue equity on a rights basis, and researchers have found evidence of substantial earnings management surrounding rights issues (Chen and Yuan, 2004; Liu and Lu, 2007). However, the lack of entry norms or reduction of disclosure requirements can also lead to potentially adverse consequences. SEBI’s assumption that existing shareholders, and, in particular, minority shareholders, would have adequate information based on the public disclosures of the firms issuing equity on a rights basis is typically not supported by studies of the quality of disclosures. These studies have found that while India receives high marks for investor protection and creditor rights, its record in practice is poor (Allen et al., 2012). Similarly, Chakrabarti et al. (2008) state that while financial disclosure norms in India are superior to those of most Asian countries, noncompliance with the disclosure norms is rampant. Other cross-country studies of investor protection also rank India low. For example, La Porta et al. (1998) find that among 18 countries following a Common Law legal system, India ranks lower than average on a set of criteria that include shareholder rights, creditor rights, rule of law and concentration of ownership. Therefore, the impact of the recent changes in SEBI DIP guidelines reducing disclosure requirements for rights-issuing firms remains to be seen.

2.3. SEBI guidelines for creeping acquisitions

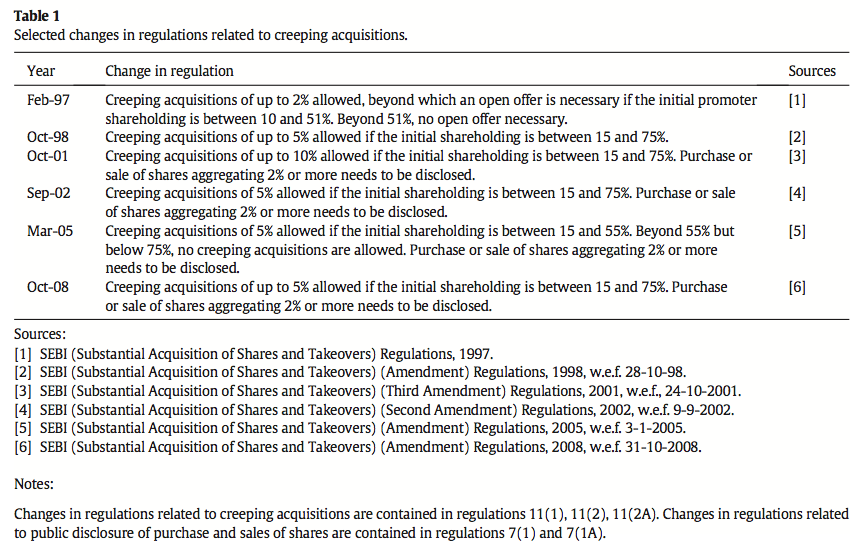

As mentioned above, the Takeover Code governs, among others, the percentage amount by which the promoters of a firm can increase their holdings via purchases in the secondary market. One of the stated objectives of the Takeover Code is to protect the interest of minority shareholders (Kumar, 2000). Table 1 shows selected regulations related to creeping acquisitions from 1997 through 2008. As shown in the table, the regulations have changed several times. The changes, in general, reflect an attempt by SEBI to balance the twin objectives of protecting the interests of minority shareholders and the ease with which mergers and acquisitions can take place to promote economic growth, particularly in a changing global economy (Kumar, 2000; SEBI, 2008).

Changes in regulations since 2008 have not significantly altered the rules regarding creeping acquisitions. For example, in 2009 the existing regulation that allowed creeping acquisition of 5% a year for promoters with ownership stakes of between 15% and 75% was changed such that promoters with stakes of between 15% and 55% were allowed to acquire up to 5% of their firms’ stake in a year. For companies with promoter shareholdings between 55 and 75%, a one-time (i.e., not annual) cumulative creeping acquisition limit of 5% is allowed (Regulations 11(2) and 11(2A) of the Takeover Code).

In 2011, the regulations were changed again such that promoters with ownership stakes of between 25% and 75% could acquire up to 5% of their firms’ equity in any one year without triggering a need for an open offer.

Regulations regarding the consequence of breaching the 5% creeping acquisition threshold have also not changed significantly since 1997. Up until the 2011, the Takeover Code (paragraph 20.4.1) required that a promoter that breached that creeping acquisition threshold of 5% ownership increase in a year, make an open offer to acquire an additional 20% of the total outstanding shares at a price that is at least equal to the higher of (i) the average of the weekly highest and lowest closing price paid by the promoter for the shares of the given company during a 26-week period, or (ii) the average of the daily high and low prices of the company during a two-week period ending on the date of announcement of the open offer. Following the recommendations of the Achuthan Committee (the Takeover Regulatory Advisory Committee that was set up by SEBI), the amount of the open offer was increased from 20% of the outstanding shares to 25% of the outstanding shares in 2011.

Thus, even after the most recent changes to the Takeover Code, any increase in promoters’ ownership through rights issues is not treated as creeping acquisition. In other words, if subsequent to a rights issue a promoter’s stake increased by, say, 6 percentage points because the promoter subscribed to the shares that were offered to but not subscribed by minority shareholders, the open offer requirement of the Takeover Code is not triggered. In India, promoters almost always underwrite their own rights issues (for the period 2002 to 2008 we found only one case where this wasn’t true); i.e., they declare in their filings to SEBI and other regulators that they will subscribe to additional shares should such opportunities arise due to undersubscription by other shareholders. The subsequent rise in promoter shareholding does not breach any provisions of the creeping acquisition guidelines, including the aforementioned Regulation 3(1)(b)(ii). Thus, a rights issue offers a route for promoters to increase shareholding by more than 5% without triggering an open offer. In Section 4, we examine the extent to which promoters have taken advantage of this apparent loophole.

2.4. Rights issues under varying creeping acquisition regimes

SEBI has been regularly changing the guidelines concerning creeping acquisition since the late 1990s (Table 1). A simple way to ascertain whether promoters’ decisions to issue equity on a rights basis are, at least in part, driven by the desire to circumvent Takeover Code regulations related to creeping acquisitions would be to see if the number of rights issues declines during periods in which regulations allow promoters to acquire a larger percentage of shares without triggering the need for an open offer.

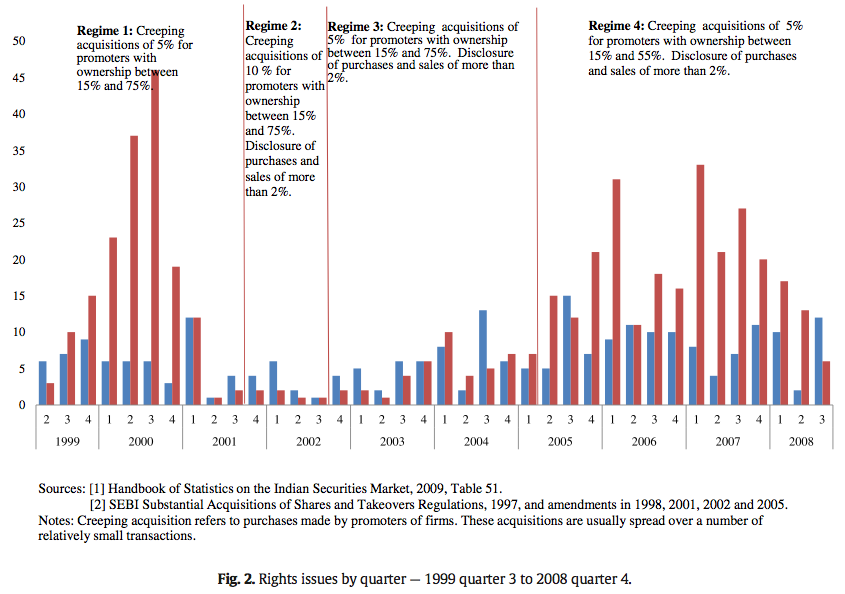

To that end, the period from April 1999 to October 2008, for which we have data on rights issues on a monthly basis from SEBI, may be divided into four distinct regulatory regimes. Regime 1 covers the period from the second quarter of 1999 through the third quarter of 2001. During this period, SEBI allowed companies with promoter shareholdings between 15 and 75% a creeping acquisition of up to 5%. During Regime 2, from the fourth quarter of 2001 through the third quarter of 2002, SEBI permitted companies with promoter shareholdings between 15 and 75% a creeping acquisition of up to 10%. In fact, there are a number of news articles about promoters taking advantage of the increase in the creeping acquisition limit and increasing their stake by over 5 percentage points. During Regime 3, from the fourth quarter of 2002 through the first quarter of 2005, SEBI effectively reverted back to Regime 1. Finally, during Regime 4, from the second quarter of 2005 through October 2008, SEBI has allowed creeping acquisition of up to 5% for promoters with shareholdings between 15% and 55%. Thus, during Regime 4, promoters with a stake of 55% or more were not allowed to increase their stakes via creeping acquisitions. Since the second quarter of 2005, SEBI has issued a number of clarifications of its regulations related to creeping acquisitions.

Based on our discussion in Section 2.2 above, we expect the number of rights issues to be roughly similar in Regimes 1 and 3, to be low in Regime 2 (because incentives to use rights issue to increase promoter shareholding reduced due to the 10% creeping acquisition threshold) and to be relatively higher in Regime 4. Fig. 2 charts the number of rights issues by quarter under different regulatory regimes. The number of rights issues in a quarter ranges from 1 to 15. Fig. 2 shows that the number of rights issues fell markedly during Regime 2.

The figure also shows that rights issues increased when SEBI subsequently reduced the amount by which promoters could increase their stake via creeping acquisitions. The averages are 6 rights issues per quarter in Regime 1, 3.25 rights issues per quarter in Regime 2, 5.7 rights issues per quarter in Regime 3, and 8.53 rights issues per quarter in Regime 4. This is consistent with our conjecture: Regimes 1 and 3 are practically identical in terms of the extent to which promoters could increase their ownership. Regime 2 allowed higher creeping acquisitions, thus reducing incentives for companies to use rights issues. Regime 4 increased these incentives, particularly for companies with relatively high promoter shares (55% or more).

The above analysis, although instructive, tells us only about the propensity of listed Indian companies to raise capital through a rights issue in response to regulatory changes. It does not analyze the changes in promoter shareholdings consequent to a rights issue. In addition, the above analysis does not control for other factors that could influence issuance of equity via rights issues. For example, the phenomenon of hot (cold) markets with respect to equity issuance is well documented, where equity issuance is high (low) in hot (cold) markets (Bayless and Chaplinski, 1996). In the next section, we develop the conceptual framework for our analysis and introduce our hypotheses to be tested in our formal data analysis that controls for various firm characteristics.

3. Hypothesis development

To investigate the extent to which rights issues are undertaken with the objective, albeit unstated, of increasing promoters’ ownership in the firm, we use a multistep methodology. First, we posit that, in a given year, rights-issuing companies realize a larger percentage increase in promoters’ ownership compared to the same for similar non-rights-issuing firms. Such a gain will be consistent with the firm’s objective of using rights issues to increase promoter shareholding. The expectation that ownership stake of promoters would increase following a rights issue is consistent with Kothare (1997), who finds that insider ownership increases around rights issues, and Holderness and Pontiff (unpublished), who find that participation rate of individual investors is lower than that of institutional investors and insiders. In our empirical investigation, we first establish this claim.

In addition, we expect that firms belonging to an Indian Business Group are more likely to have incentives to increase promoter shareholding through a rights issue, and therefore will register higher increases in promoter shareholding subsequent to a rights issue compared to stand-alone firms. Our hypothesis that promoters of firms belonging to a business group are more likely to seek an increase in ownership is consistent with the literature on private benefits of control and tunneling. For example Wu et al. (in press) posit a rent protection theory to explain decisions regarding equity flotation. Per the rent protection theory, the decision regarding equity flotation — rights issues verses other methods — is driven by concerns about private benefits of control. With respect to tunneling, Bertrand et al. (2002) show that Indian business group firms engage in tunneling, and control of shareholding rights is crucial to this. Also, as documented by Claessens et al. (2000) and Gopalan and Jayaraman (2012), business group firms in East Asia engage more in earnings management linked to private benefits of control. Thus, it seems reasonable that promoters of firms belonging to business groups are likely to be more incentivized to add to their shareholding. We formalize this in the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1A. Rights-issuing firms experience a greater increase in promoter shareholding compared to non-rights-issuing firms in the year of rights issue.

Hypothesis 1B. Rights-issuing companies belonging to business groups experience a greater increase in promoter shareholding subsequent to the rights issue compared to the stand-alone rights-issuing firms.

However, the fact that promoters of rights-issuing firms see a greater increase in ownership stake than similar non-rights-issuing firms is not surprising, given that the promoters underwrite the rights issue. Thus, one cannot draw any conclusion regarding the extent to which the rights issue was done with an objective of increasing the promoter’s stake.

To gain insight regarding intent, we first examine the evolution of promoter holdings prior to the rights issue. We conjecture that promoters who experience a reduction in their holdings are likely to be the ones who would have an incentive to undertake a rights issue to recoup the loss in ownership. The notion that promoters who experienced a decline in their ownership stake may be the ones seeking to use rights issues as a mechanism to regain their stake is consistent with the rent protection theory regarding equity issuance (Wu et al., in press), as well as with Cronqvist and Nilsson (2005), who posit that firms with greater family control make issuance decisions in an effort to maintain their control. The proposed hypothesis is also consistent with the literature on business groups and their use of internal capital markets. In less developed capital markets, firms in a business group serve as an internal capital market to each other with significant intra-group loans (Gopalan et al., 2007; Khanna and Palepu, 2000), which in turn gives insiders incentives to protect their equity stake in firms. Our second hypothesis is stated as:

Hypothesis 2A. Promoters of rights-issuing firms experience a relatively large reduction in their ownership in years leading up to rights issues. That is, firms that lose promoter shareholding are more likely to have a rights issue in subsequent years.

We also examine the cause of the decline in promoter ownership to see if one can gain better insight regarding intent. In general, promoter ownership, in percentage terms, can decline because of two reasons — sale of shares by the promoter, or issuance of shares to other shareholders such as a joint venture partner. One can think of sale of shares resulting in an absolute reduction of a promoter’s holding, while increase in equity capital results in a relative reduction of the promoters holding (reduction in percentage of shares held without reduction in number of shares owned or controlled by the promoter). We explore the extent to which the cause of the decline in promoter holdings, absolute verses relative, can shed additional light on promoters’ equity issuance decision. A reduction in promoter ownership due to temporary factors, such as a need for liquidity, is more likely to manifest as an absolute decline rather than a relative decline in promoter ownership. Similarly, a reduction in promoter ownership related to a strategic decision such as issuing shares to, say, a joint venture partner is likely to manifest as a relative decline in the promoter’s ownership rather than an absolute decline. We conjecture that promoters who experienced an absolute decline in ownership are likely to be more incentivized to try to gain back the lost stake. Our conjecture is consistent with the literature on the extent to which equity issuance decisions are driven by concerns regarding private benefits of control (Cronqvist and Nilsson, 2005; Wu et al., in press). Thus, we summarize a variation of the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2B. Firms where promoters have experienced an absolute loss in ownership are likely to be more incentivized to use a rights issue to try to increase their stake in comparison to firms where promoters experience a relative decline in ownership.

We recognize that loss in holdings may not be the only reason that a promoter may be motivated to increase ownership. Other possible reasons, such as achieving the long-term targeted (steady state) ownership level, could also be a plausible cause for promoters to seek to increase their stake. However, a strong relationship between the decision to do a rights issue and decline in promoter holdings in prior years provides useful insight regarding intent.

Not all rights-issuing firms are likely to be motivated by a desire to increase promoter shareholding. In particular, firms that need cash infusion to fund specific projects are unlikely to be motivated by a desire to increase promoter shareholding, and any increase in promoter shareholding is likely to be incidental. Eckbo and Masulis (1992) model equity flotation method choices made by firms based on the premise that the net benefit of the issuance is positive. In other words, the difference between the net present value of the project being funded with equity and the cost of equity issuance is positive, where the cost of issuance includes direct and indirect flotation costs. However, to the extent that a firm is issuing equity with the objective of helping the promoter increase his stake, one would not expect the Eckbo and Masulis (1992) model to hold. One way to identify such instances would be to identify rights issues where the funds are not being raised for a specific project purpose.

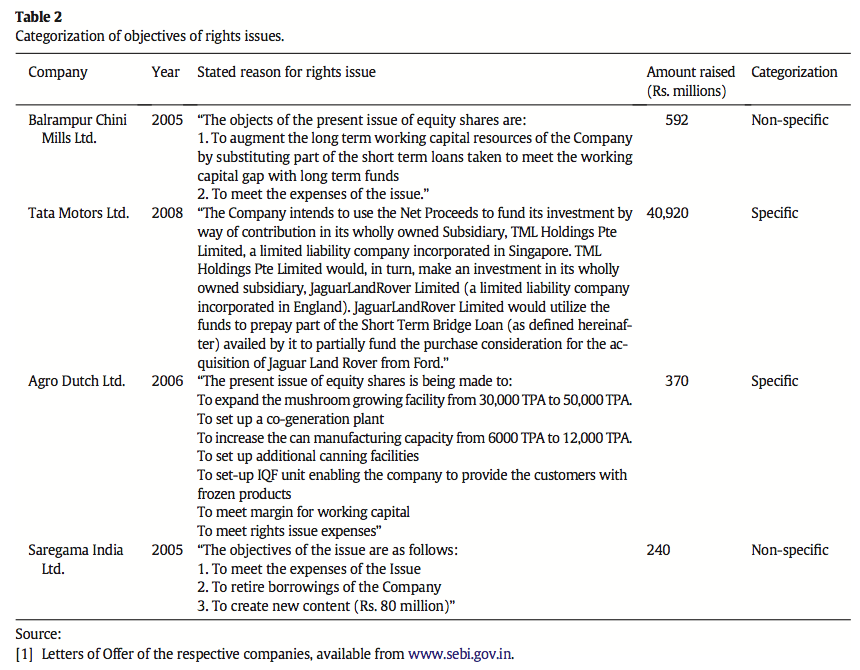

Thus, we look into the objectives of rights issue as described by the firms in their Letters of Offer to SEBI (similar to Form S-1 filed in the US) to gain some insight. We apply a simple algorithm to distribute rights issues into two categories. The first category includes firms that provide information on specific projects. We categorize the first group as one that includes rights issues with “specific objectives.” The second category includes rights issues where the company discloses that more than 50% of the proceeds from the issuance are to be used to augment working capital or repay debt (the “non-specific objectives” category). Our methodology is consistent with the methodology used by Masulis and Korwar (1986), who categorize the planned use of proceeds of equity issuances by US firms. We conjecture that the rights issues motivated by promoters’ desire to increase their holdings are likely to fall in the second category. We demonstrate our categorization for a few companies in Table 2. For instance, we categorize the rights issues by Tata Motors Ltd. and Agro Dutch Company Ltd. as having specific objectives, whereas those of Balarampur Chini Mills Ltd. and Saregama India Ltd. are categorized as being non-specific.

The hypothesis that promoters seeking to increase their ownership via a rights issue may try to do so with a rights issue with non-specific objectives is predicated on the assumption that, all else equal, participation by minority shareholders in a non-specific rights issue is likely to be lower. The underlying assumption is consistent with Jostarndt (2009), who notes that, due to concerns about wealth transfer from owners to debtors, equity issuances to reduce debt are less likely to be successful. Similarly, Masulis and Korwar (1986) show that reduction in leverage can signal lower future cash flows. We formalize our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. A rights issue that has non-specific objectives will be more strongly correlated with promoter share gains subsequent to the rights issue.

Finally, we examine incentives of promoters who may be seeking to increase their ownership stake by over 5% in a year. In particular, we expect that promoters with ownership levels close to but under certain thresholds have a greater incentive to use rights issues as a mechanism to try to orchestrate a 5-percentage-point ownership increase using a rights issue. We test for two specific ownership thresholds — 45% and 25%. The 45% threshold is based on the fact that passage of ordinary resolutions requires greater than 50% of shareholders to vote in favor. We conjecture that promoters with a stake of at least 45% can increase their stake to 50% via acquisitions in the open market (i.e., creeping acquisitions) without worrying about breaching the 5% threshold that would require an open offer. The 25% threshold is based on the fact that special resolutions in India require a 75% shareholding, thus owning 25% or more gives the promoter blocking rights or negative control.

4. Empirical analysis

4.1. Data

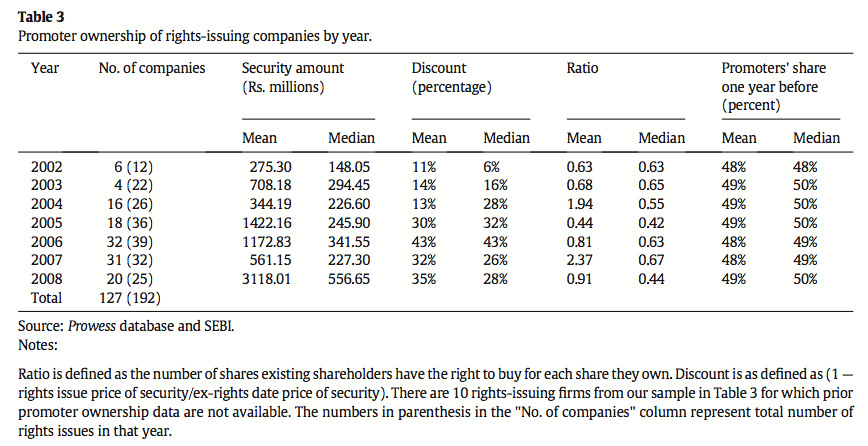

The data for our analysis of rights issues by Indian public companies come from the Prowess database from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (“CMIE”). Our initial sample consists of Indian firms offering rights issues from financial years 2002 through 2008, when Regime 4 ends. We limit our analysis to issuance of rights shares only — we exclude issuance of rights shares with warrants or issuance of other forms of equity such as convertible debentures or preferred stock. Out of the initial sample, we drop any instances of rights issues by financial firms, such as banks or non-bank finance companies, because for such firms issuance of equity on a rights basis may be driven by the need to comply with certain capital adequacy norms set by the Reserve Bank of India — the Indian central bank. In addition, observations for which the amount of money raised or the rights share ratio (the number of rights shares a shareholder may buy for every share owned as of the ex-rights date) is not available are excluded as well. We also drop rights issues for which the capital issue date and ex-rights date differed by more than 365 days, as well as rights issues of less than Rs. 10 million. Next, we merge the data on rights-issuing firms with data from Prowess on firms listed on the BSE, and drop any rights-issuing firms not listed with the BSE, which results in a sample of 127 rights issues from 2002 through 2008 out of a total 192 rights issues during this period (Table 3). The rights-issuing firms in our sample form a diverse group in terms of their ownership characteristics, as well as of the industries they represent. Over 40 industry categories are represented, covering manufacturing, services and agro-based industries.

The summary statistics of the rights-issuing firms are presented in Table 3. The average amount of capital raised from the rights issues varied from Rs. 275 million in 2002 to Rs. 3.1 billion in 2008, while the median amount of capital raised varied from Rs. 148 million in 2002 to Rs. 556 million in 2008. Table 3 also shows that the median discount for the rights issues ranged from 6 to 43% of the ex-rights date share price, which seems rather large compared to seasoned equity offerings in other countries (see Section 2.1 for details). However, in a few cases, the shares were sold at a premium. The median ratio of shares offered to shareholders per units of shares held varied between 0.42 (approximately two for every five shares held) to 0.67 (approximately two shares for every three shares held). Finally, Table 3 shows that the average (mean) ownership stake of the promoters one year prior to the rights issue was quite high — it ranged between 48 and 49% for the period 2002 through 2008.

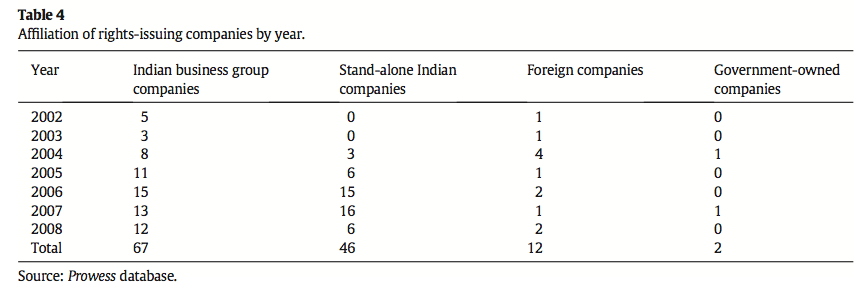

Table 4 provides information on the ownership structures of firms offering rights issues from 2002 through 2008. For the purposes of our analysis, we divide the rights-issuing firms into four ownership groups: firms belonging to Indian business groups; listed Indian companies that do not belong to a business group (stand-alone firms); foreign companies (firms promoted by non-Indian businesses); and government companies (listed firms in which the Indian Government is the majority shareholder). More than half of the rights-issuing firms (67 of the 127 firms) belong to an Indian business group, and 46 of the rights-issuing firms stand-alone firms. The table also shows that only a few foreign firms and government firms issued equity on a rights basis from 2002 through 2008.

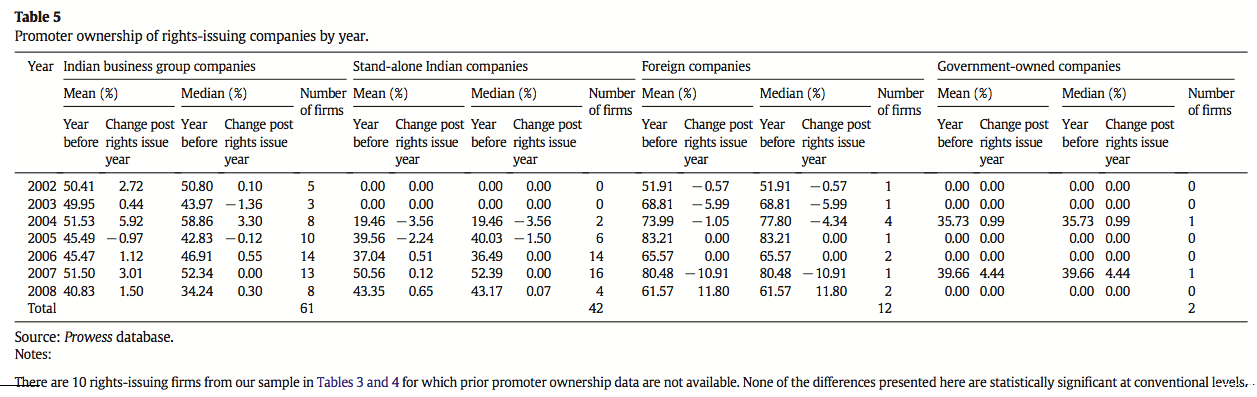

Table 5 shows promoter ownership of the rights-issuing firms before and after the rights issues by different ownership categories. As noted in footnote 1 to Table 5, there are 10 firms in the original 127 firms in Table 4 for which prior year ownership data are not available, and thus, the total sample size becomes 117 for Table 5. Since ownership data are available only on an annual basis in the Prowess database, the table compares promoters’ stakes in the year prior to the rights issues to their stakes in the year of the rights issue. The table shows that promoter ownership levels were generally high for firms belonging to an Indian business group or foreign firms. By comparison, promoter shareholding in stand-alone firms prior to rights issue is lower. Table 5 also provides some insight into the pattern of changes in promoter ownership following rights issues by firms belonging to different ownership groups. In particular, the recorded changes in shareholding subsequent to a rights issue were higher for Indian business group companies than other groups in almost all years.

A comparison of the change in promoter ownership following a rights issue within a firm type but across years shows that in later years the increase in promoter ownership declined. In particular, increase in promoter ownership following a rights issue is much smaller during Regime 4, which starts in the second quarter of 2005. As discussed in detail later, the lower increase in ownership may have been triggered by a change in capital gain tax rates starting from October 2004. In particular, long-term capital gains tax was reduced from 20% to under 0.2%, which makes it easier for a minority shareholder to realize the offering discount by selling shares in the secondary market and then buying them back via the rights issue. Alternatively, a shareholder could sell or relinquish all or part of the rights issues that are allotted to him. However, we did not find any evidence of a market that facilitated such transactions.

In order to establish a link between changes in ownership and rights issues, one needs to control for other possible explanations of the observed increase in the promoters’ stakes in firms issuing equity on a rights basis. In the next section, we benchmark the changes in promoters’ shares of firms issuing rights equity to those of comparable firms that did not issue equity on a rights basis. We also run tests that provide insight into the intent of the rights issue, to try to determine if promoters do actually issue equity with an objective to increase their stake.

4.2. Regression models, tests of hypotheses and results

To establish a benchmark for changes in promoters’ stakes, we select a set of control firms. First we limit our analysis to domestic private firms, i.e., we exclude government and foreign firms. Government firms are excluded because it is unlikely that government-owned firms will use rights issues in order to increase their stake. Foreign firms are excluded because incentives of promoters of foreign firms are likely to be different from those of promoters of Indian non-government-owned firms. This is because, in general, regulations during 2002 to 2008 did not allow foreign firms to operate in India through wholly owned subsidiaries. Next, for each non-government and non-foreign-owned firm with a rights issue from 2002 through 2008, we identify comparable firms by first identifying all firms in the Prowess database in the same industry and ownership category (i.e., Indian business group or stand-alone). Then, among firms in the same industry and ownership category, we isolate firms with similar revenues — firms with revenues within 40% of the revenues of the rights-issuing companies in at least two of the years 2001–2008. The purpose of this is to ensure that the firms have similar ownership category, have the same industry affiliation and are somewhat similar in their earnings. We keep at most 5 comparables for each rights-issuing firm.

Table 6 compares the rights-issuing firms and their comparables along several dimensions. Based on our methodology, we could identify comparable firms for 78 of the rights-issuing firms. The table shows that, on average, rights-issuing firms were larger in terms of overall assets and had lower debt-to-equity ratios than the comparable firms. The table also shows that promoter shareholdings in the rights-issuing firms were slightly smaller than in the comparable firms.

4.2.1. Increase in promoters’ shareholding following a rights issue

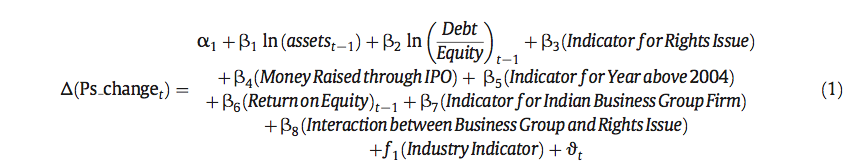

Recall that Hypothesis 1A seeks to compare the change in promoter shareholding between rights-issuing firms and comparable firms. To examine the extent to which the change in promoter share in a firm is related to a rights issue, we use the following regression model.

Δ(Ps _ changet) is the change in promoters ownership. For firms issuing equity on a rights basis, Δ(Ps _ changet) is the difference in the promoter’s stake in the firm as of the end of the year in which the rights issue was completed from that of the prior year. For comparable firms used as a benchmark for a particular firm with a rights issue, Δ(Ps _ changet) is the change in the promoter’s stake during the period used to compute the promoter ownership change for the rights-issuing firm. The average change in the promoter stake subsequent to the rights issue is denoted by the constant term α1. The model includes an indicator variable for rights-issuing firms (Indicator for Rights Issue) and an indicator for business group firms (Indicator for Indian Business Group Firm). TheIndicator for Rights Issue will isolate the impact of the change in promoter stake related to the rights issue, whereas the Indicator for Indian Business Group Firm isolates increase in promoter ownership for a business group firm within a year. Our test for Hypothesis 1A and Hypothesis 1B comprises examining the value of coefficients corresponding to these variables. In particular, we expect both β3 and β8 to be positive. The interaction between the rights-issuing firms and the firms belonging to Indian business groups (coefficient β8) is expected to isolate the extent to which the change in promoter ownership of rights-issuing firms that belong to an Indian business group differs from that for other types of firms that issue rights equity.

In the model, we control for a few firm-specific characteristics — size and leverage. Ln(assetst − 1) for the rights-issuing firms and the corresponding benchmark firms is the natural logarithm of assets as of the year-end prior to the year in which the rights issue was completed. We expect the change in ownership to be lower for larger firms. Ln(Debt/Equity)t − 1 for the rights-issuing firms and the corresponding benchmark firms is the natural logarithm of the debt-to-equity ratio (defined as the ratio of total borrowings to net worth in Prowess) as of the year-end prior to the year in which the rights issue was completed. There are two possible and opposing effects of a high level of debt in a company. Firms with higher leverage may be perceived to be more risky, and, all else being equal, purchase of shares by minority shareholders of riskier firms might be lower in general. On the other hand, debt may be helpful in reducing agency costs of free cash flow (Jensen, 1986), and thus make a firm more attractive to shareholders. However, given that rights-issuing firms are seeking to raise additional capital, on balance, we expect the change in ownership to be larger for firms with higher leverage.

To control for market-wide appetite for equity, issued on a rights basis or otherwise, we include the amount of money, in billions of rupees, raised via an IPO in the year in which the rights issue was done. Using the amount of funds raised in IPOs is consistent with the method used by Bayless and Chaplinski (1996) to identify periods of hot and cold markets. As we discuss below, the capital gains tax was reduced in years subsequent to 2004. A reduction in capital gains tax, coupled with the fact that rights issues are priced at a discount to the market, suggests that subsequent to 2004 investors would have a greater financial incentive to participate in a rights issue in order to realize the issuance discount. To control for the change in the tax regime we use an indicator for post-2004 tax regime. To control for measures of firm performance, we introduce the lagged values of Return on Equity for the companies in question. We also include indicator variables for various industry categories. Specifically, we reclassified the industry categorization from Prowess into four broad categories: Manufacturing, Agricultural, Other Financial Services and Services.

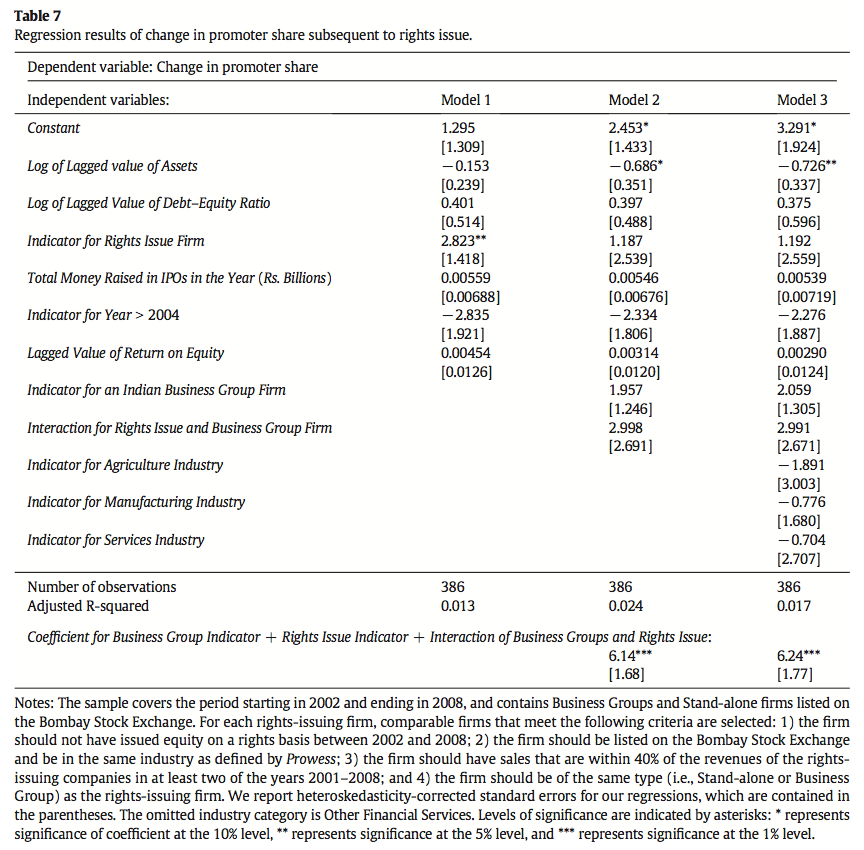

We run three specifications. The first specification is the model with the firm characteristics variables, including a control for firm performance, the general market condition and tax regime variables and the Rights Issue Indicator variable. In Model 2, we introduce the indicator for business group firms and the interaction between the indicator for firms belonging to a business group and the Rights Issue Indicator. In Model 3, we add industry indicator variables to Model 2.

The results are reported in Table 7. The table shows that the lagged value of assets has a negative impact on the change in promoters’ ownership, and is statistically significant for specifications 2 and 3. Also, leveraged firms experience increase in promoters’ share, but the effect is not statistically significant for any specifications. Ignoring controls for business group and industry, the Indicator for Rights Issue variable is positive and statistically significant. General market conditions, as captured by the amount of money raised through IPOs in a given year, and lagged return on equity have no meaningful impact on increase in promoter shareholding. For instance, an increase in overall IPO raised in a year of Rs. 10 billion will result in an increase in promoter shareholding of 0.5%. The change in tax regime has resulted in promoter shareholding being lower in general for all firms, but this is not significant for any specifications. The table shows that firms with a rights issue, on average, had an increase of about 2.8 percentage points in the promoters’ stake compared to benchmark firms without a rights issue, controlling for the various firm characteristics. The table also shows that even after controls are included for business groups, in Models 2 and 3, the coefficient for the Indicator for Rights Issue variable remains stable but is not statistically significant.

Models 2 and 3 show that business group firms, regardless of whether they have a rights issue or not, increase promoter shareholding by close to 2%. Further, the interaction between rights-issuing firms and firms belonging to a business group is positive but not statistically significant. However, the cumulative impact of rights issuing on promoter shareholding for a business group firm in the rights issue year is obtained by adding the coefficients of: a) the indicator variable for business group affiliation; b) the indicator variable for rights issues; and c) the interaction between the indicators for business group affiliation and rights issues. Calculated this way, we find that promoters’ ownership in business group firms with a rights issue increased by 6.14 and 6.24 percentage points in Models 2 and 3, respectively. Thus, the results demonstrate that rights issues help promoters of firms increase their ownership stake and promoters of firms belonging to a business group realize an even larger increase in ownership stake subsequent to a rights issue. Our results are therefore consistent with the conclusion that rights issues help promoters circumvent the creeping acquisition provisions of the Takeover Code, as claimed in Hypothesis 1A and Hypothesis 1B. Controlling for differences in broad industry categories makes no difference to this conclusion.

4.2.2. Investigating intent

In order to examine the extent to which a rights issue was motivated by the promoter’s desire to increase shareholding, we first reviewed the prospectus for each of the 78 rights-issuing firms in the final sample. Rights issues were distributed into two buckets — issues with specific objectives and issues with vague objectives. Table 2 lists a few of the 78 rights issues, and how each of the issues was categorized. As stated above, rights issues in which more than 50% of the proceeds were proposed to be spent on specific projects were put in the specific bucket; the others were classified as having non-specific or vague objectives. We categorized 36 of the 78 rights issues as having non-specific objectives, and the other 42 as issues with specific objectives.

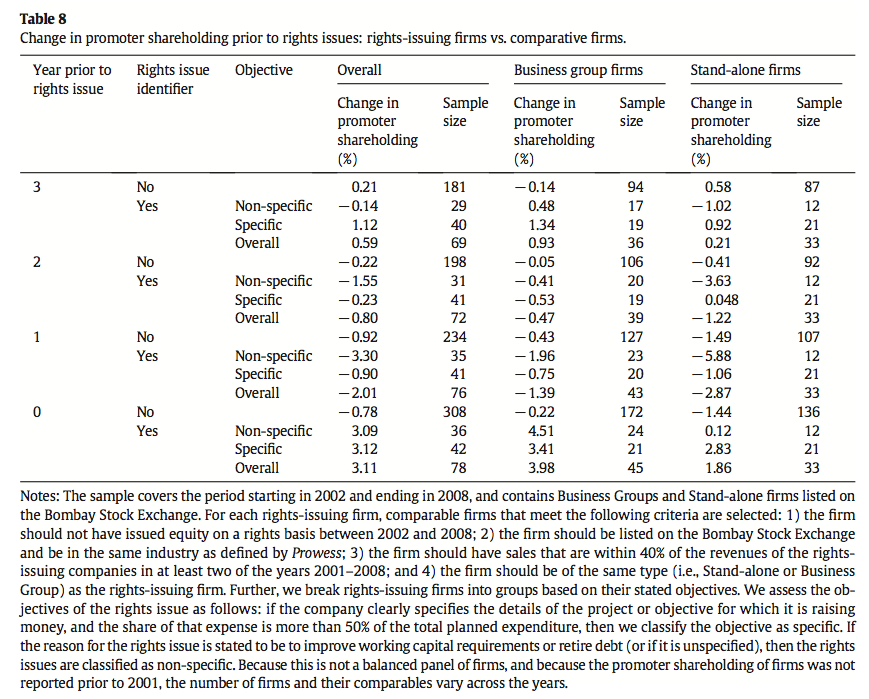

Next, we examine the evolution of promoters’ shareholding in the years leading to the rights issue. Table 8 shows the change in equity ownership of promoters of rights-issuing firms and comparable firms during a three-year period prior to the rights issue. Rights-issuing firms are also broken down by objective — non-specific or specific. The table shows that one year prior to a rights issue, the ownership of promoters of all rights-issuing firms falls by about 2 percentage points, while equity ownership of promoters of comparable firms falls by about 0.9 percentage points. As shown in Table 8, promoters of rights-issuing firms with non-specific objectives have a decline of about 3.3 percentage points, which is over three times greater than the average decline of comparable non-rights-issuing firms. This difference is significant from both a statistical (a p-value of 0.03) and an economic perspective. Table 8 also shows that change in promoters’ holdings during the three-year period for rights-issuing firms with specific objectives is not significantly different from that of comparable firms.

Table 8 also allows a comparison based on the type of firms — stand-alone versus those belonging to a business group. The table shows that firms belonging to a business group seem to have a greater tendency for rights issues with vague objective. For example, 45 of the 78 rights-issuing firms belong to a business group, and 24 of these 45 rights issues (53%) had non-specific objectives. On the other hand, 12 (35%) of the 33 rights issues by stand-alone firms had non-specific objectives. While the difference is large, a proportions test shows that the difference is not statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.14.

The information presented in Table 8 suggests that loss of promoters’ holdings may help predict a rights issue, especially a rights issue with non-specific objectives. Hypothesis 2A predicts that the rights-issuing decision is positively related to prior loss in promoter shareholding. To test if loss of promoter holdings can help predict a rights issue, we ran the following logistic regression model:

where yi is a firm-specific indicator variable that identifies a rights-issuing company. For measures of prior loss of promoter shareholding, we consider two measures. The first measure is an indicator for loss of at least 3% of promoter shareholding over the 3 years leading up to a rights issue. The choice of 3% as the threshold of loss of shareholding is admittedly arbitrary, and is intended to capture relatively large losses in promoter shareholding over a period of time. Our results are robust to other choices for this threshold, such as 4% or 5%. We also consider another measure: the total change in promoter shareholding for the year prior to rights issue. According to Hypothesis 2A, the coefficient β1 is expected to be positive and significant. We introduce controls for size (assets), the debt–equity ratio (leverage) and return on equity (performance). Finally, we include indicators for different broad industry categories.

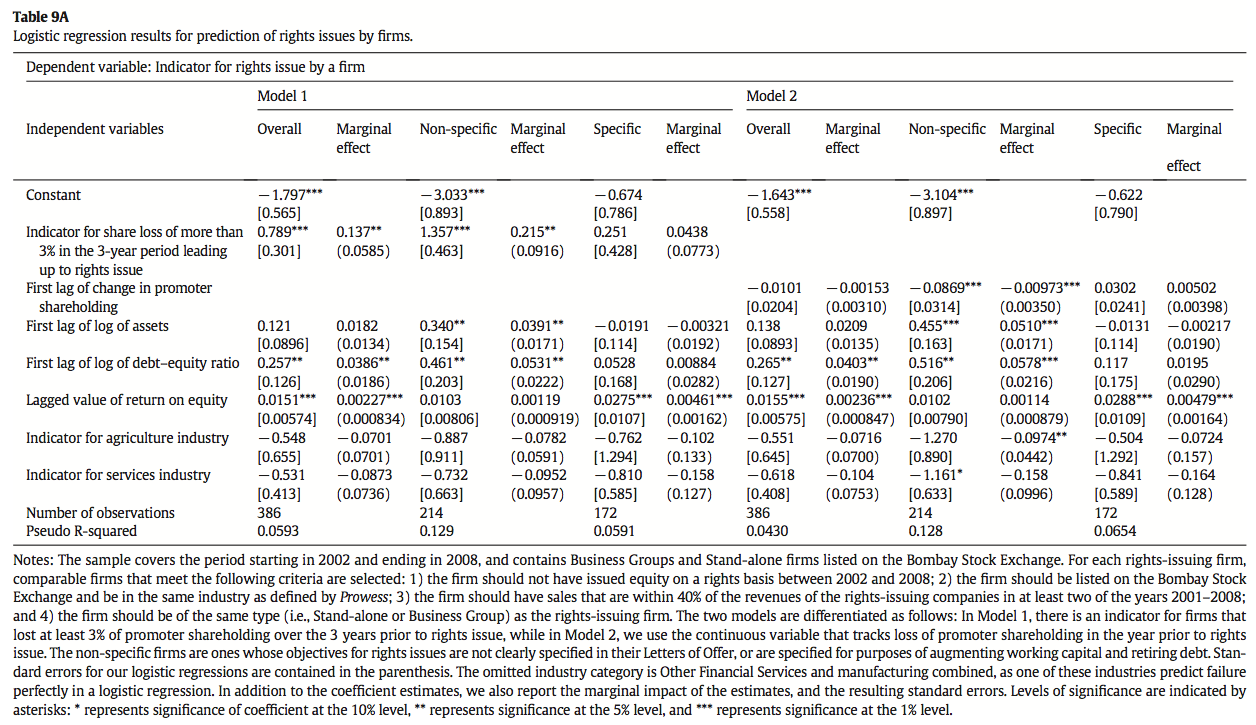

The results are presented in Table 9A, and report coefficients as well as marginal effects. We run the models for all rights-issuing firms and their comparables, and also separately for rights-issuing firms with project-specific reasons and non-project-specific reasons. The results show that the indicator for loss of promoter shareholding of more than 3% over the 3 years leading up to the rights issue is positively correlated with the rights-issuing decision, which is consistent with Hypothesis 2A — prior loss in promoter shareholding is strongly associated with the rights-issuing decision. Furthermore, bifurcating the rights-issuing firms by objectives shows that this result is driven by the firms with non-specific objectives. While the coefficient for the firms with specific objectives is positive, its magnitude is much smaller compared to rights issues with non-specific objectives, and it is not statistically significant either The results of the second model, using the first lag of change in promoter shareholding, are consistent with those of Model 1. Firms that had a decrease (increase) in promoter shareholding had a higher (lower) propensity for a rights issue, and this effect is strong for firms with rights issues with non-specific objectives. The results indicate that larger firms (with higher lagged return on assets) are more likely to go for a rights issue, and leverage is also positively associated with the rights-issuing decision.

In addition, as posited by Hypothesis 3, the results presented in Table 9A demonstrate that the likelihood of a rights issue with non-specific objectives is much higher for firms with a high level of loss in promoter ownership (“Model 1 Non-Specific” and “Model 2 Non-Specific”), whereas the likelihood of a rights issue with a specific objective is unrelated to prior loss in ownership (“Model 1 Specific” and “Model 2 Specific”). This is consistent with Hypothesis 3 — promoters seeking to increase their stake via a rights issue are likely to do so with the help of a rights issue that has non-specific objectives.

Next, we incorporate cause of the decline in promoter ownership in our analysis to gain better insight regarding intent. As discussed above, we categorize the observed percentage declines in promoter ownership as absolute and relative, where absolute declines correspond to sale of shares by the promoter and relative declines are associated with issuance of shares to other shareholders through private placements or partnership in a joint venture (or both). In particular, we modify Model 1 in Table 9A by replacing indicator for loss of promoter shareholding of more than 3% over the 3 years leading up to the rights issue with two indicator variables. One of the two new indicator variables takes the value of 1 when there is a 3% or more absolute loss in promoter ownership, while the other variable captures instances where the decline in promoter ownership of more than 3% is due to capital expansion (i.e., instances of a relative decline). In instances in which a promoter’s ownership has fallen by more than 3 percentage points because of both selling and capital expansion, we categorize the loss as absolute or relative based on the type of decline that contributes more to the observed decline. Thus, if 2.5 percentage points of a 3.5-percentage-point decline can be attributed to selling of shares, then the observed loss is treated as an absolute loss. Our baseline group consists of companies that did not have a decline in promoter shareholding of 3% or more.

Table 9B shows that both relative loss and absolute loss are positively correlated with the propensity to do a rights issue. However, only the coefficient for absolute loss (i.e., sales of shares) is statistically significant. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 2B, and it provides a more nuanced understanding of why promoters may seek to use rights issues as a mechanism for increasing their shareholding. While the results in Table 9A suggest that promoters who realize a 3-percentage-point reduction in ownership stake may be incentivized to do a rights issue, Table 9B suggests that promoters who lose ownership due to previous sale of shares are the ones with a stronger incentive.

4.2.3. Examining stake increase of 5 percentage points or more

Next, we examine incentives of promoters who may be seeking to increase their ownership stake by over 5% in a year. We test for specific ownership thresholds — 50% and 25%. Implicit in our approach is the assumption that promoters seek to increase ownership in order to increase control over their firms. Thus, we expect the incentives to use rights issues to increase promoter ownership by over 5 percentage points to be higher when the ownership is below the 25% and 50% threshold. Rights issues are particularly appealing for increasing stake because, first, promoters can acquire shares at a discount to the prevailing market price (see Fig. 1); and second, increases in ownership caused by participation in a rights issue do not trigger the need for disclosure or an open offer under the Takeover Code.

We run the following logistic model to examine factors that may explain a relatively large increase in promoter ownership following a rights issue. A relatively large change in holdings is defined as change of 5 percentage points or more. The 5-percentage-point threshold is based on the limit on creeping acquisitions mandated by the Takeover Code.

The dependent variable y is an indicator variable that is equal to one if the promoter’s ownership increases by more than 5 percentage points immediately following a rights issue. Immediate change in ownership is equal to the difference between the promoter’s ownership as of the year-end following the rights issue and year-end ownership in the prior year. We also include the natural logarithm of assets as of the year-end prior to the year in which the rights issue was completed, with coefficient γ1. We expect the likelihood of an increase in promoter shareholding of 5 percentage points or more to be smaller for larger firms. We also include the natural logarithm of the debt-to-equity ratio, or leverage, as of the year-end prior to the year in which the rights issue was completed. We expect leverage to have a positive relationship to the likelihood of a change in ownership by 5 percentage points or more because, as discussed above, we expect leverage to be negatively associated with minority investors’ participation in a rights issue. In general, we expect past performance to be positively associated with participation of minority shareholders in a rights issue. Thus we expect higher past profitability (measured by ROE) to be negatively associated with a 5-percentage-point increase in promoter holdings subsequent to a rights issue.

For a given firm, the discount is the ratio of the difference between the price of a stock on the ex-rights date and the issue price, and the price as of the ex-rights date. We expect the discount to be negatively related to the likelihood of a change in promoter ownership of 5 percentage points or more. This is because deeper discounts are likely to solicit greater participation by other shareholders.

We distribute firms into three buckets based on ownership level of promoters prior to the rights issue: promoter shareholding between 15% and 25%, promoter shareholding greater than 25% but less than or equal to 45%; and the rest. Recall that we exclude firms with a rights issue where the promoter’s ownership prior to the rights issue was less than 15%, because creeping acquisition rules do not apply to acquisitions by promoters who own less than 15%.

The first bucket — ownership between 15 and 25% — tries to isolate instances where a promoter, at least on paper, does not have enough votes to exert negative control, but is restricted from acquiring more than 5% in a year due to creeping acquisition provisions. The next bucket — ownership between 25 and 45% — isolates promotes who have a large stake but their stake falls short of owning 50% of the votes that would give them ability to pass ordinary board resolutions without support from any other shareholder. As a caveat, it is well established that the actual number of shares controlled by an Indian promoter are likely to be much larger than the amount owned because promoters can routinely count on support from shares held by friends, family, and financial institutions who tend to be passive shareholders and vote with the promoter (Verma, 1997). Thus, the reported ownership level may not be reliable for purposes of examining promoters’ incentives for increasing their ownership in order to increase control.

Additionally, we introduce indicators for the post-2004 period when long-term (i.e., holding periods of more than 1 year) capital gains taxes were eliminated, which increased the incentives of retail investors to subscribe to rights issues; industry controls; and an indicator variable for business group ownership. We also introduce controls for whether a firm has indicated a project-specific purpose behind the rights issue, and conjecture that for such firms the likelihood of increase in promoter shareholding by 5% or more is likely to be lower.

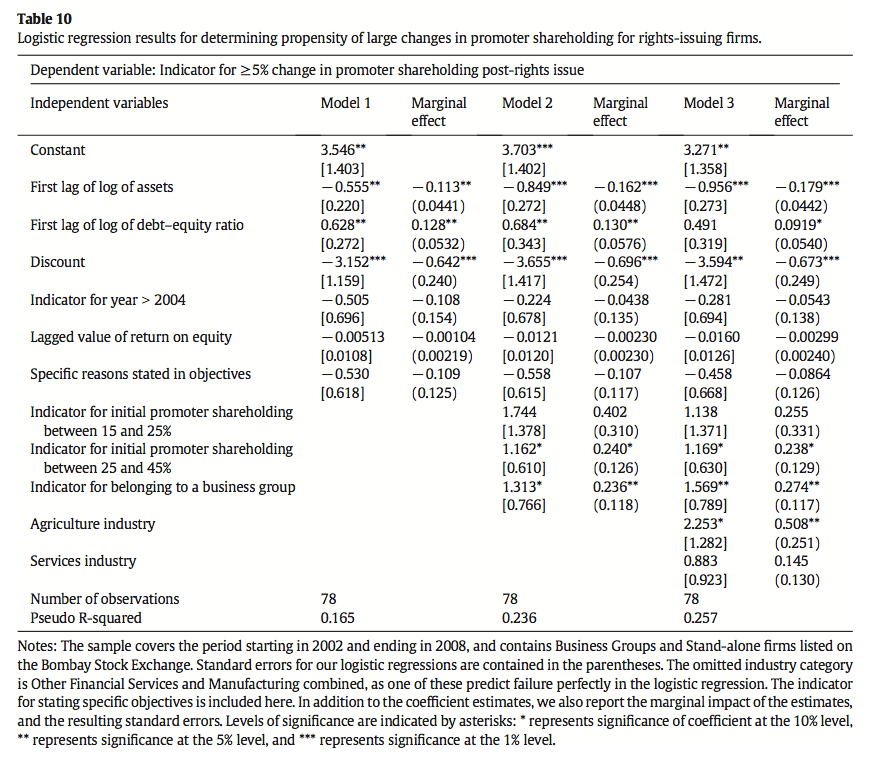

Table 10 shows the coefficients as well as the marginal impact of each variable for the logistic regressions. Size of firms, as measured by the logarithm of assets in the previous period, is negatively related to the propensity of large shareholding increase. First lag of the log of debt–equity ratio has a positive impact. The results confirm that the higher the discount, the less likely it is that the promoters’ share will increase by 5 percentage points or more.

Impact of ownership level is mixed. While prior ownership levels are correlated with propensity to increase shareholding by more than 5 percentage points, none of the ownership buckets are significant at conventional levels. The results also show that a specific objective regarding a rights issue has a negative impact on the likelihood of 5-percentage-point increase in ownership; however, the coefficient is not statistically significant. Similarly, the coefficient on lagged ROE is negative but not statistically significant. The coefficient for the indicator variable for a firm belonging to a business group is positive and significant, suggesting the proclivity of business groups to try to use rights issues to get around creeping acquisition provisions.

4.3. Discussion

Our results raise a few questions related to minority shareholders’ and promoters’ incentives to participate in a rights issue. In particular: a) why aren’t minority shareholders taking advantage of discounted rights issue prices to reap short-term gains; and b) why are the promoters motivated to increase their shareholding, given that they already own substantial portions of the company? We address these issues in turn.

4.3.1. Shareholders’ Incentives

Conceptually, rights issues shouldn’t affect the distribution of ownership. For the promoters to be able to increase their shareholding through rights issue, the minority shareholders will have to under-subscribe to the issue, which will enable the promoters to subscribe to any shortfall by the remaining shareholders. Given that rights issues, on average, are offered at substantial discounts, one would expect every shareholder to subscribe to the issue in order to realize the resulting capital gains. In other words, even shareholders who do not seek to increase their holdings of the rights-issuing firm on a long-term basis should participate to realize the short-term gain of buying stock at a discount and then selling the same at a higher market price subsequent to the issue. Alternatively, in a well-functioning capital market, a shareholder could also simply sell shares and the accompanying rights prior to the ex-rights date, and the buyer would then subscribe to the rights issue. We posit that taxes and transaction cost most likely limit the ability of minority shareholders to realize short-term gains associated with rights issues.

Transaction costs could limit the ability of shareholders to realize the discount associated with a rights issue. This is especially true for individual shareholders who hold a relatively small number of shares. While we are not aware of any studies that measure the transaction costs in the Indian securities market, price bands established by SEBI for individual securities do provide some insight regarding transaction costs. Price bands represent the maximum allowable change in the value of a security — any change greater than the threshold could result in automatic cancellation of orders by SEBI, unless SEBI is provided information regarding the reason for the price change and the authenticity of the transaction. The objective of the price bands is to manage volatility and prevent spurious transaction (SEBI, 1997). The price band applicable for warrants is 20% (National Stock Exchange of India Ltd, 2003). This suggests that a rights holder seeking to sell the warrants that entitle purchase of additional shares could be asked to share a large fraction of the discount with the broker and/or the buyer.

In addition, studies from countries with developed capital markets could be used to shed some light on the transaction costs involved in trading illiquid shares. Armitage (2007)estimates that there are substantial transaction costs (measured in terms of half-touches, defined as half of bid-asked spreads divided by average of bid and asked price) even for institutional shareholders for rights-issuing shares in the UK, which makes it difficult for shareholders to trade shares with discounted rights issue. As in the case of the UK, we also find that the average market capitalization of rights-issuing firms is lower than that of the top 100 firms on the Bombay Stock Exchange, and therefore, it is likely that trading in the rights-issuing firms involves at least similar transaction costs. Because this deters many shareholders from selling the additional shares accruing through rights issue subsequently in the market, many such investors may choose not to subscribe to the rights issue. The company, perhaps realizing this, goes ahead with the rights issue, with the expectation that not many shares will be taken up, which will allow the promoters to increase their shareholding.

As discussed before, gains from sale of stock are subject to capital gains taxation. In India, prior to 2004, short-term capital gains were taxed at the normal rate of ordinary income taxation, and long-term capital gains (for shares held for more than a year) were taxed at a rate of 20%. Post-September 2004, short-term capital gains were taxed at 10% (subsequently increased to 15% from fiscal year 2008–09), and long-term capital gains are not taxed provided a securities transaction tax (STT) has been paid beforehand. If STT has not been paid, then long-term capital gains are taxed at a rate of 20% with indexation benefits or at 10% without indexation benefits.

Thus, shareholders seeking to realize a discount associated with a rights issue would also need to take into account the related tax impact. Given that the first-in-first-out rule is used in India for purposes of computing capital gains taxes, for many shareholders buying shares via a rights issue and selling them subsequently is likely to trigger significant tax obligations. Given that tax rates, especially long-term tax rates, fell sharply in 2004, all else being equal, one would expect to see an increase in participation in rights issues by minority shareholders. In other words, the change in the tax regime starting from October 2004 should limit the extent to which promoters can increase their ownership via a rights issue, as reduced taxes would reduce the cost of buying shares via a rights issue and then selling the same number of shares in the secondary market.Table 5 corroborates our intuition. The table shows that for 2002, 2003 and 2004, the change in promoter ownership following a rights issue was relatively large.

4.3.2. Promoters’ incentives

What incentives do promoters have to do a rights issue and/or concentrate even more shareholding? In other words, why do promoters seek more control? As our results suggest, this incentive is at its highest when the prior shareholding is somewhat low. In our opinion, in markets where there are private benefits of control, a controlling shareholder would have an incentive to raise money through a rights issue and to undertake a project because the controlling shareholder would expect to realize private benefits associated with a project.

Another reason for controlling promoters to increase their shareholding through a rights issue could be to support other firms in the same business group. For example, Gopalan et al. (2007) find that Indian firms belonging to business groups transfer capital internally to weaker firms in the group to help them avoid default on external debts. Our finding is that Indian business group firms are more likely to have an increased promoter shareholding subsequent to rights issue. To the extent that such capital transfers are facilitated when promoters have higher shares in the weaker firm in the group, the promoters have incentives to increase their shares, even when they control the company.

Finally, if the promoters have inside information about the prospects of the controlled firm, they have incentives to increase their shareholding. Rights issues offer a cheap way to raise capital for the company’s projects and, in many instances, also lead to increases in promoter shareholding. When the company rebounds, the promoters reap larger benefits due to a higher shareholding.

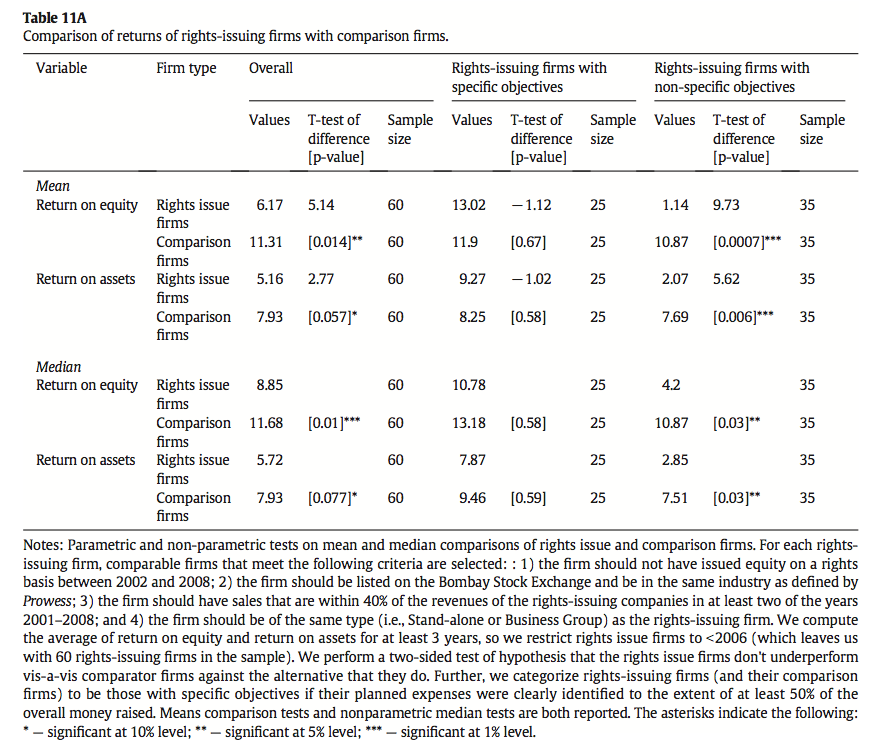

4.3.3. Policy implications

Regulators such as SEBI are obviously concerned about improving corporate governance and protecting the rights of minority shareholders. In fact, regulations related to creeping acquisitions are an attempt to protect the rights of minority shareholders from promoters who may seek to time increases in stake based on private information. Our study provides evidence for relatively significant increases in promoters’ interest following a rights issue. While, clearly, not all rights issues are motivated by promoters seeking to increase their stake at discounted prices, there is anecdotal evidence that indeed, some promoters do try to use rights issue as a mechanism to increase their shareholding. For example, in the case of the rights issue by Pentagon Global Solutions, a number of news articles mentioned that the purpose of the issue was to allow the promoters to increase their stake; in the case of Hitachi’s rights issue, SEBI required the company to make an open offer to all shareholders after irregularities concerning acquisition of shares by promoters surfaced following the rights issue (Express India, 2004). More recent anecdotal evidence also suggests that, even in 2012 and 2013, rights issues were being used by promoters to increase their stake. Specifically, following a rights issue in 2012 by EPC Industrié Limited (“EPC”) — a firm belonging to the Mahindra & Mahindra Group — the promoter’s stake increased from 38.1% to 54.8%. In fact, an Economic Times news story dated June 20, 2012 covering the EPC rights issue stated that, “rights issues have proved to be a convenient route for promoters to strengthen their holdings as acquisition of shares through rights is not subject to take-over guidelines, according to investment bankers.” Similarly, a large increase in promoter holdings followed the rights issue by Kesoram Industries in 2013. So, are minority shareholders being harmed by rights issues? We offer some evidence that this is indeed the case. Marisetty et al. (2008) show that while the price reaction to a rights issue is generally neutral, it is significantly negative for a business group firm. Jijo Lukose and Rao (2003) show that the long-term performance of rights-issuing firms, measured in terms of abnormal returns, are also worse relative to firms without a rights issue. Following Loughran and Ritter (1997), we compare the average return on equity and return on assets of rights-issuing firms. Specifically, we compare the average of the return on equity and return on assets over a three-year period following the rights issue. Table 11A shows that the return on equity and the return on assets of rights-issuing firms are lower than those of comparable firms. This difference is both statistically and economically significant. The table also shows that the underperformance is entirely driven by firms that do not provide specific objectives in connection with a rights issue.

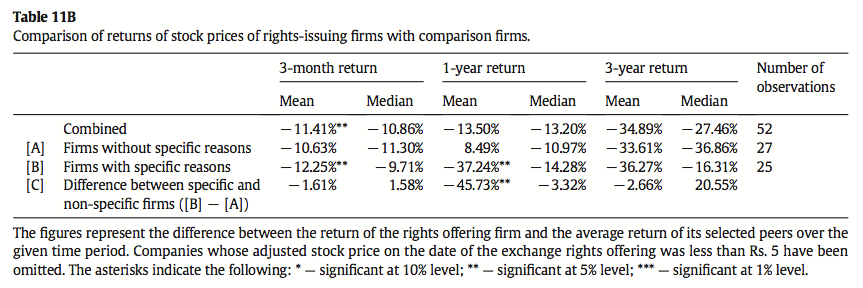

Next, we compare the stock price performance of rights-issuing firms to that of their peers. Specifically, for a given rights-issuing firm, we compute the difference between its stock returns and those of its peer group over a 3-month, one-year and three-year period starting from the ex-rights date. We restrict this analysis to firms that traded consistently during the three-year period starting from the ex-rights date, and to firms that had a price of at least Rs. 5 on the ex-rights date. Thus, a negative number indicates that the rights-issuing firm underperformed its peers. Overall, Table 11B shows that, consistent with results of other studies, stock returns of rights-issuing firms underperform the returns of similar but non-rights-issuing firms. And with respect to stock price returns, the underperformance is not affected by the distinction between rights issues with and without specific objectives.