Publications Divestitures: How To Invest For Success

- Publications

Divestitures: How To Invest For Success

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Sean O’Connell, Michael Park, Jannick Thomsen – McKinsey & Company

When it comes to creating value, divestitures are critical – but a positive outcome is not automatic. Some up-front investment can improve the odds of success.

Senior executives often have a hard time letting go. When it comes time to decide whether to sell certain assets, particularly those that have become less relevant to the core business, many bosses hold on for too long, only to watch as value withers and the assets become costly distractions. Others are simply more focused on acquiring or turning things around and, as a result, fail to prune noncore assets or divest even those businesses that destroy value. The effect on shareholder returns is more than you might imagine: our analysis of the largest 1,000 global companies finds that those that are actively involved in both acquiring and divesting create as much as 1.5 to 4.7 percentage points higher shareholder returns than those focused primarily on acquisitions.

Yet creating value through divestitures isn’t automatic, and how much a company can gain depends heavily on planning the right approach. For some deals, such as auctions or those that involve businesses in decline with minimal customer overlap, managers may want to sell at the best price with the fewest strings attached – and then just walk away. But for others, such as spin-offs and situations where businesses’ performance could be improved by better owners or with shared customer bases, there are nuances to preparing and structuring deals that affect both the price and the potential for creating long-term value. The range of value created or destroyed between top- and bottom-quartile performers after a spinoff, for example, is striking compared with market averages (Exhibit 1). This is especially true in the first year after a divestiture, when parent-company performance ranges from 37 percent higher shareholder returns to 100 percent lower, relative to their benchmarks, even after adjusting for company-specific factors. The substantial difference illustrates the risk in what are typically material business disruptions for the parent company and the spun-off company alike.

The most successful companies for these types of deals are those that take a more thoughtful approach to divestitures. Our colleagues have highlighted a number of themes important to such planning, including shaping deals around a buyer’s needs and managing stranded costs. Our latest research and work suggest others – requiring a modest investment in time, thinking, and resources – that are often overlooked but can make the difference between a good deal and a poor one. For example, are you preparing for suitors before you need a buyer? Have you really considered your potential buyers’ point of view on the deal details that would create value? And finally, are you investing to boost the chances of the success of a divestiture for both your company and your buyer?

Prepare for suitors before you need a buyer

Companies often don’t sufficiently evaluate their businesses as candidates for divesting. That leaves them unprepared to generate the most interest for those assets among potential buyers – and to act expediently – when the pressure to divest becomes unavoidable. The most successful portfolio managers we’ve seen address these circumstances by embedding divestitures into their regular portfolio-review process, evaluating businesses at least once a year for their strategic importance and operational value. One challenge is the inclination of division leaders to aggressively avoid divestiture discussions, protecting assets by overstating their importance to sales and synergies, and effectively burying the discussion in process.

Companies that are actively involved in both acquiring and divesting create as much as 1.5 to 4.7 percentage points higher shareholder returns than those focused primarily on acquisitions.

A key method to address this tendency is to put in place a scoring system, based on algorithms and tailored by criteria linked specifically to a company’s industry and strategy. It’s possible to rate, for example, growth versus margin, required management resources, operations complexity, and how much an asset distracts managers and resources from other activities that create more value. With those criteria in mind, executives can then be asked to articulate a reason to retain low-scoring businesses. The result could be a list of businesses to consider divesting.

Executives at one Fortune 100 company, for instance, compel leaders of business divisions to identify annually the three least core, highest-potential divestiture candidates and detail the rationale for keeping them – typically based heavily on size, growth potential, and burden to manage. Corporate leaders themselves make the final decision to keep or divest, explicitly removing that responsibility from the division leader’s hands. This overcomes internal conflicts and biases before they obstruct critical decision-making processes.

Expand your view on the pool of potential buyers

It can be hard for executives to know the true value of a noncore business, since their perspective is often so anchored to their own perceptions of it that they can’t fully appreciate its potential value to others. This is especially true if the business has been a laggard relative to peers, difficult to manage, or just a neglected part of the portfolio. The challenge is to take a fresh, deep view and clearly identify which attributes of a deal might attract a broader pool of better owners willing to pay more for an asset.

There’s almost always significant value at stake, especially on issues of talent retention, service agreements, and the organizational structure of the parent company once the divestiture is complete. On such issues, even seemingly minor details that the buyer and seller appreciate differently can meaningfully change the value of a deal. In a recent divestiture in the pharmaceuticals industry, for example, production agreements controlling a shared supply chain constrained the buyer to just a fifth of the sales it could have made in some regions if the deal had more flexibly allowed for growth. Similarly, a recent divestiture in the defense industry was complicated by ownership-control clauses in contracts with suppliers and customers that restricted the pool of buyers. And in the technology and industrial sectors, decisions about allocating and licensing intellectual property can affect the value of a deal for both buyer and seller –and have implications for customer relationships as well.

Savvy managers know it isn’t easy to counteract cognitive biases, such as anchoring, even when you’re aware of them. But working to identify and address these issues early on can expand initial thinking and better direct a seller’s search for a buyer. Most managers start by talking to bankers, the more obvious potential owners, and CEOs in the industry. But these groups often share the same biases. A broader search might require talking to CEOs of a wider set of potential owners, private-equity managers, or experts outside the seller’s immediate circle of industry insiders to secure different perspectives on a deal’s potential sources of value to others. One highly successful CEO we know, who has considerable experience in divestitures, reports that discussions with external experts, such as retired industry executives or boutique advisers with deep industry experience, often help him overcome the biases he knows he has and add substantial value to his deals.

Invest for mutual success

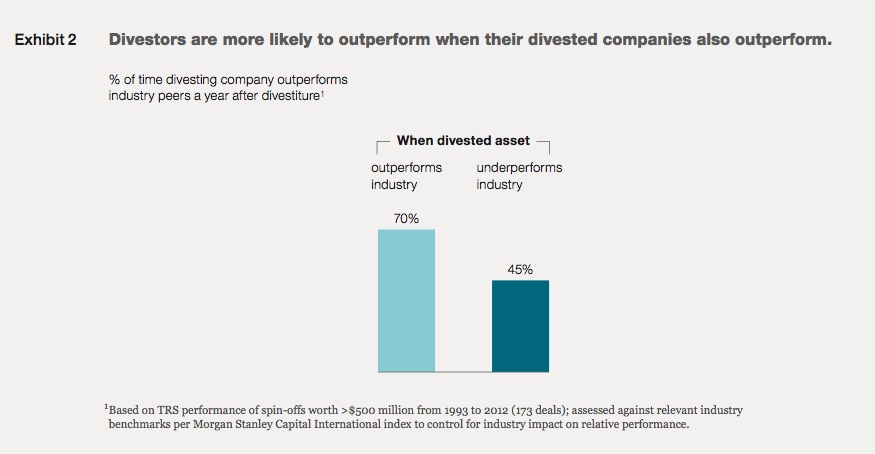

Poorly prepared deals become costly distractions to parent-company managers, creating dissatisfaction among shared customers, causing top talent to flee the divested company, and depressing morale at both companies. Even deals where companies would prefer to sell a business for as much as they can get and just walk away can come back to haunt the seller if the divested business greatly stumbles before sale or alienates mutual suppliers or a shared customer base. The impact on postdeal performance can also be substantial for buyer and seller alike – and their fates appear to be linked. In our analysis, divestiture deals are either successful for both the divesting company and the acquirer or failures for both nearly two-thirds of the time. The case of spin-offs is once again illustrative; our analysis suggests the divesting company is dramatically more likely to outperform industry peers when its spin-off also exceeds relevant industry benchmarks (Exhibit 2).

For many deals, senior leaders should focus as much attention on preparing divestiture candidates for postdeal success as they do on negotiating the best price relative to its book value. That includes, for example, defining what success will look like for the divested asset after a deal closes. Its performance measures are often quite different from that of its former parent, reflecting a wide range of new internal and external stakeholders, all with their own motivations. Those measures should be realigned with the new owner as early as possible – in our experience, as early as 12 months before a deal closes. That requires the divesting company to develop a deep understanding of the asset’s potential sources of value.

The CEO of one industrial company takes the time to develop meticulous memos and support documentation that go well beyond the usual business case, for instance, outlining specific elements of strategy and high-potential operational improvements. In his experience, this extra attention is valuable for him as well as the new owners of a divested asset, and it greatly increases the quality of execution.

Ensuring success also requires that the right managerial talent is involved. Many deal leaders we speak to lament the lack of adequate resources for executing divestitures, especially when compared with the resources typically committed to an acquisition. This is a costly imbalance. Once candidates have been identified, senior managers should be tasked with implementing a highly structured process, including investing in select operational improvements and accelerating disentanglement initiatives. It is critical to keep managers motivated by communicating their high value to the company, reinforcing a sense of opportunity connected to the divestiture, and instilling as much confidence as possible that performance will be rewarded. The impact will reverberate and have beneficial impact across the organization and on the parent company’s postdeal performance.

One leading technology company has dedicated divestiture leaders with years of experience in charge of running companies until they are sold. Another large medical-products company often puts top managers in charge of divesting units to maximize business growth and facilitate the hand-off to buyers. This has earned the company a reputation as a seller of great businesses, attracting potential buyers for future deals, smooth- ing negotiations and buyer due diligence, and greatly accelerating sales process times and value creation.

Divestitures are a critical but often overlooked and undermanaged part of shaping a company’s portfolio of businesses. Investing the right resources before a sale can help attract better suitors who will make stronger offers for a deal that creates more value for them – and who create fewer headaches down the road.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter