Publications Creating More Value For China’s M&A

- Publications

Creating More Value For China’s M&A

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Jian Sun, Sherri He, Joachim von Hoyningen-Huene, Andreas Graef, Thomas Luedi, Frankie Leung, Jürgen Rothenbuecher, Bastian Sauerberg – A.T. Kearney

Since China first opened to the world with the 1978 economic reforms, the country’s GDP has made unprecedented progress. It is a remarkable growth story. Although there is a big gap to close to catch up with the United States, China ranked second in the world in real GDP by 2013. By 2014, 100 Chinese companies were in the Fortune 500, up from 11 in 2000 and with petrochemical firm Sinopec holding the number-three spot.

For a long time, many Chinese companies grew, driven by industrialization and urbanization creating a hunger for resources and energy. Since 2010, the spotlight has shifted to the country’s vast consumer base and growing domestic consumption. Players already serving global markets on a “factory of the world” export business model with cost-competitive products made in China began to eye mergers and acquisitions to access important resources, technologies, and know-how. Those looking to enter global markets pursued M&A to access advanced products and strong brands in order to become more competitive and elevate their brand image to open doors to new markets.

The country has seen several successful examples of M&A-driven growth. Lenovo merged with IBM and became a leading global manufacturer of computers, SAIC bought the Rover technology and platforms, China National Chemical Corporation initiated several global deals to gain access to technologies and new products. Private companies such as Geely have also found success. The Chinese automotive manufacturer’s 2010 acquisition of Volvo added a premium brand and important platform technology to an overall portfolio of lower-priced cars, which helped improve Geely’s brand reputation around the world.

But expanding globally is no easy task. For Chinese companies, the main barriers are unfamiliarity with new markets, a too-standard technology and product offering—often the result of years of meeting Chinese consumers’ demands for high-value-for-the-money products—and the poor perception of Chinese brands and services in mature markets. Another challenge is negative public opinion about Chinese companies’ outbound deals, which often come with factories and jobs being kept abroad.

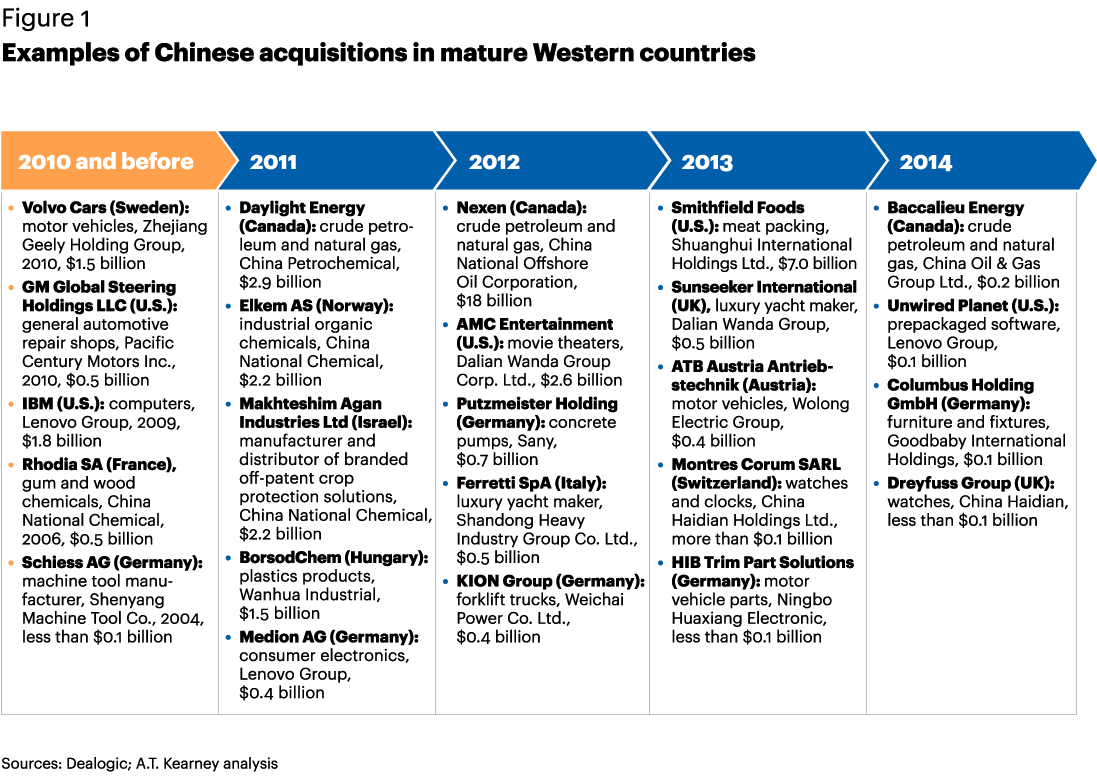

Opportunities are opening up for Chinese players to expand into both mature and emerging markets by acquiring Western companies and offering a range of products and services tailored to consumer and business requirements in each market, from high value and low price to high quality and high price (see figure 1). However, experience shows that most outbound deals have not created value because Chinese companies had to overpay or were not able to capture operational synergies, and despite a growing number of global deals over the past few years, many mergers are still not creating much value. In the pursuit of expansion outside of China, many are failing to avoid the most common pitfalls.

The Rise of M&A in China

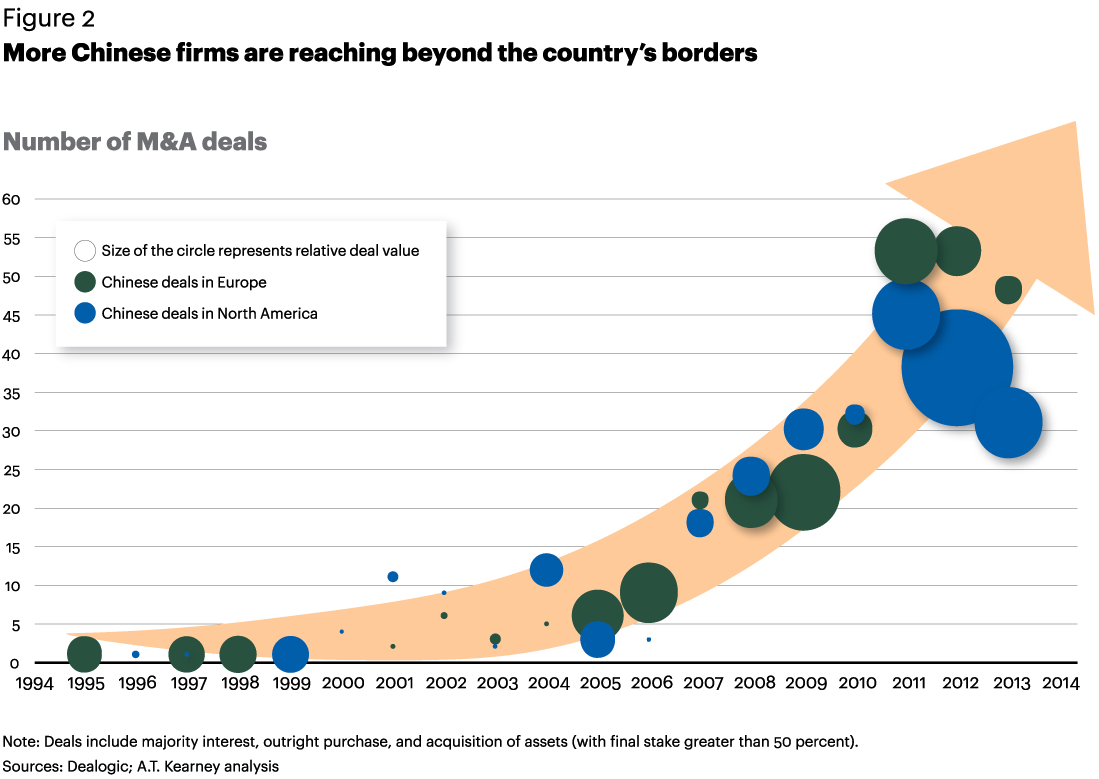

In little more than a decade, M&A deals in China have increased by a factor of 20, from 69 in 2000 to more than 1,300 in 2013. Chinese acquirers account for the major share by far of all developed-country acquisitions by developing countries. In 2014, for outbound deals into Northern America and Europe, the United States was the main target with 14 percent, followed by Germany and the United Kingdom sharing third place with 12 percent each. Most Chinese outbound deals are acquisitions, with only a few being mergers, such as the Lenovo and IBM merger.

Before 2005, there were few outbound acquisitions from Chinese acquirers with European and North American companies, but both the number and volume of deals have skyrocketed since then (see figure 2). In 2013, there were 48 deals in Europe and 31 in North America. Germany, in focus since only 2011, chalked up 18 acquisitions in 2012. In the coming years, Germany and the United Kingdom are likely to outstrip the United States as target countries.

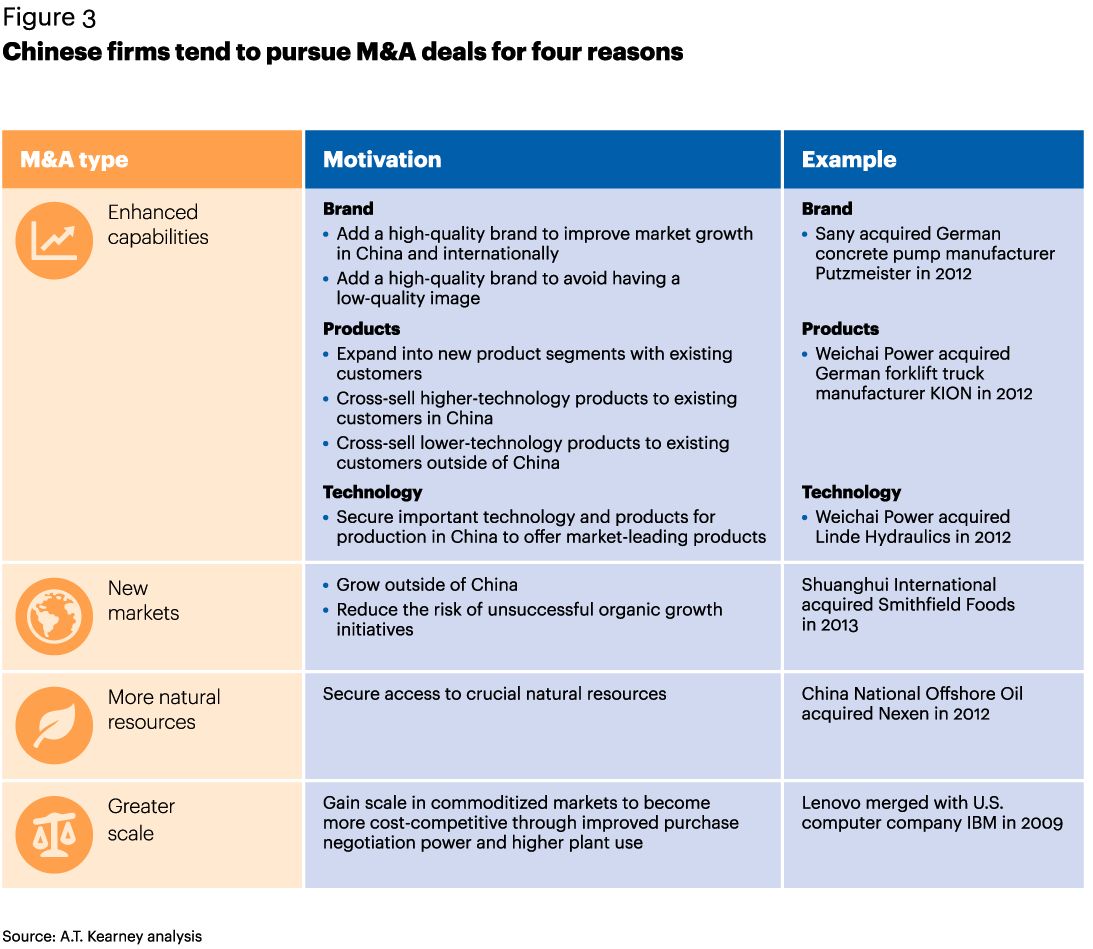

Depending on the acquirer’s situation and growth objectives, Chinese firms tend to pursue M&As for four reasons (see figure 3). For example, Chinese acquirers have targeted European and North American companies to improve their market positioning and obtain higher-quality products, with a focus on industrial machinery and tools (24 percent), utilities (12 percent), and automotive (12 percent). Prominent examples include Sany’s 2012 buyout of concrete pump manufacturer Putzmeister and Weichai Power’s acquisition of a major share of forklift truck manufacturer KION Group.

Avoiding the M&A Pitfalls

Although the success factors differ depending on the type of merger, best practices exist throughout the entire M&A process, and leading players have embraced them. For example, when Sany acquired Putzmeister, it ensured close alignment within the management team by nominating Putzmeister’s CEO to its board of directors.

Yet many players underestimate important strategic aspects and the overall pre- and post-merger process—from target selection and transaction strategy to merger integration and value generation. As a result, many mergers are not sufficiently prepared and managed. In fact in the first few years mergers often lead to market capitalization value losses, revenue growth slowdowns, and profitability losses.

The growing number of M&A deals leads to one overriding question: How can China’s acquirers sidestep the common pitfalls to create more value? These pitfalls can quickly derail a merger. For example, recent acquisitions of machinery companies show that the lack of a sound strategy from day one can impede a solid integration and the targeted value generation. Prioritizing speed over thoroughness in both the due diligence process and deal execution can leave both parties disappointed. In addition, a lack of international experience and misunderstanding the way business is done in another country can be major obstacles to growth. In Germany, for example, product development is a risk-averse process with commercialization happening only after the development is finalized, but in China it is an iterative process with continuous improvements along the product’s life cycle. In China, price and quick commercialization are crucial, but in Germany, quality is of utmost importance. Such misunderstandings during the transaction phase can lead to expectations that most likely will not be met.

Based on a review of recent Chinese outbound M&A activities, expert insights, and project experience, we have identified 10 pitfalls of Chinese outbound acquisitions across the two major transaction phases and offer best practices for avoiding them.

Target selection and transaction strategy

Firms looking to expand through acquisition face four pitfalls in this phase. Long-term strategic thinking and due diligence can help capture more value (see “Finding the Perfect M&A Target”).

Pitfall: Reactive and opportunistic deals that lack a sound strategy from day one. Most deals are done reactively. Targets are pursued because they are “available,” relying on the deal flow from investment banks. Competitors often follow by securing options on similar targets. Hence, acquisitions are opportunistic rather than thoroughly derived activities from the overall business strategy.

Best practice: Be proactive, put a development team in place, and develop a long-term strategy for globalization. Create an M&A strategy based on the company’s globalization strategy, and clearly differentiate a phased approach for both emerging and mature markets. Put a business development team in place, and establish target lists based on the strategic imperatives.

Pitfall: No thorough analysis of the target and a lack of insights and capabilities. A high-level examination conducted ahead of M&A activities is often inadequate. As many deals in China are done on net asset value, Chinese companies often find it difficult to properly assess the commercial value of the target and synergies and risks related to the potential deal. There is often a lack of insights into the target’s market.

Best practice: Assemble a cross-functional team of experts, and conduct full strategic, operational, and financial due diligence. Take advantage of the experience and competencies of third-party professionals by assembling a cross-functional team of experts (both internal and external) that understand markets and financials, including lawyers, M&A specialists, and management consultants. Consider assessing the cultural gap of both companies.

Pitfall: Unclear objectives of the post-merger integration (PMI). Often, there is no dedicated, experienced, and neutral internal M&A team. Chinese companies often rely on advisors who get incentives to close the deal. Hence, the goals of the PMI—what is supposed to happen during and after the merger—are not well-defined before the M&A transaction.

Best practice: Install an internationally experienced M&A team to define strategy for the acquired target and the derived integration concept. Put in place a high caliber, internationally experienced M&A team to manage the advisors, rather than the other way around. Assure continuity of the acquired business. Learn about the target’s business in existing organizational structures. Plan how to effectively link both companies, starting with top management.

Pitfall: Lack of international exposure. For example, the target region’s performance results are often misunderstood because the acquirer underestimated the respective country’s way of doing business.

Best practice: Capitalize on third-party experts for international markets. Assess market and company specifics with comprehensive due diligence.

Finding the Perfect M&A Target

The Chinese acquisitions of two German companies are good examples of sound M&A strategy in the target selection and transaction strategy phase.

In 2005, Beijing No. 1 Machine Tool Plant acquired German machine tool manufacturer Waldrich Coburg. A thorough due diligence, conducted by a global team, enabled the Chinese management to find the perfect M&A target for the firm’s strategic purposes. The companies’ products, regional market positions, and technologies complemented each other well. Over the following years, sales orders and gross profit shot up, making the integration a success.

In 2005, Beijing No. 1 Machine Tool Plant acquired German machine tool manufacturer Waldrich Coburg. A thorough due diligence, conducted by a global team, enabled the Chinese management to find the perfect M&A target for the firm’s strategic purposes. The companies’ products, regional market positions, and technologies complemented each other well. Over the following years, sales orders and gross profit shot up, making the integration a success.

The 2008 acquisition of Germany’s Vensys Energy AG by China’s Xinjiang Goldwind Science & Technology shows how challenges can be mastered. Goldwind’s strategy was well-defined: Vensys Energy could bring the design and development know-how for large-scale wind turbines to Goldwind, which manufactured midsize wind turbines. Goldwind kept the operations of Vensys Energy independent and ensured that both companies would be closely connected through their senior management teams. The first years after the acquisition have been successful, with both companies strengthening their market positions and expanding their portfolios globally.

Merger integration and value generation

Mastering the PMI process is the best way to create optimum value in this phase. Several Chinese acquirers have let European or U.S. companies stay operationally independent. Nonetheless, one key to success is having a joint vision and common management structures to boost the value of both companies. Failure to drive the integration and value generation process often leads to dissatisfaction and distrust on both sides. One pragmatic way to overcome this issue is by contracting a mediator to help the two parties join forces to become more powerful.

Pitfall: Lack of active management of the PMI process. Synergies are not properly identified, and there is no value creation. Active management often happens too late and frequently only at board level, with some attempts to transfer technology and products but with insufficient depth.

Best practice: Develop a joint vision on synergies, and implement quick wins. Thoroughly analyze synergies at the beginning of the integration process. Implement quick wins in pilot areas to motivate the entire organization and lead by example. Build a foundation for synergies. For example, use a German quality leader for China, and have Chinese engineers working in Germany.

Pitfall: Underestimated complexity of PMI. PMI, an intrinsically complex undertaking, is made more complex in cross-border Chinese acquisitions by distance, language, and fundamental cultural differences. The extent of these additional complications is difficult to predict and their impact often underestimated.

Best practice: Establish a PMI program office. Even if it is a “light” version, make the commitment to drive value creation. Employ a mediator who understands both sides, using the languages and methods of both parties to bring the firms together to implement a joint vision.

Pitfall: Underestimated cultural differences. Miscalculating cultural diversity—from business habits, values, and management processes to language skills and education—can lead to misunderstandings and frustration. For example, many U.S. companies are comfortable working with a stretched target and achieving 80 percent of it, but Chinese companies often want to surpass their targets. As a result, the business target discussion deteriorates.

Best practice: Assign or hire multilingual Chinese or foreign managers to be an interface for both companies. Conduct business and country culture and language training for the management teams of both companies. Use interpreters, and make sure the companies align on the management and performance tracking approach.

Pitfall: Organizational setup not ready for the merger. Each company’s top management and management organization is unprepared for the integration.

Best practice: Build global organizational structures in advance. Take advantage of the experience and knowledge of external experts for international organizational aspects of the PMI. Start discussing new organizational structures with the target companies at an early stage.

Pitfall: Governance structures and responsibilities not leveraged to reach higher performance. Chinese companies often undermanage the acquired companies by integrating only the board of directors.

Best practice: Apply a balanced approach, and aim for higher performance. Give freedom while taking the lead. Challenge senior and middle management to improve performance. Prepare decision-making bodies and governance processes to be put in place immediately after the closing. Every side has to win some responsibility.

Pitfall: Lack of regular internal and external communication. For example, there is no communications plan for internal staff, external suppliers, and customers.

Best practice: Establish a joint communications team covering all major functions. For example, create a structured customer communications plan to avoid customer churn during the PMI while convincing new and existing customers about future opportunities in products and services that will be available through the acquisition.

Paving the Way for Success

As domestic growth slows and margins decline, global M&A will become even more important. In parallel, a stronger consolidation of companies in China will improve the financial situation of leading Chinese companies across industry sectors, which will further increase outbound M&A activities. However, the entire M&A process—from target selection and due diligence to merger integration and value generation—has pitfalls that can jeopardize acquisitions.

To learn from the past and start capturing significant value in outbound M&A, Chinese companies need to treat M&A like any other important management process, such as R&D, manufacturing, and sales. Give it top priority, and staff it permanently with highly skilled people. Pursue the right targets, and structure the right deals. Push for operational integration and global asset optimization. Forward-thinking players that take these best practices into account will be better prepared to reach beyond China’s borders and capture significant growth and value with smoother, more successful acquisitions.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter