Publications Carve-Outs: The New Darling Of M&A?

- Publications

Carve-Outs: The New Darling Of M&A?

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Sven Wahle – Accenture

The value of being proactive and strategic

Last year, Philips NV accepted an offer from private-equity firms to purchase a majority stake in its lighting components and automotive-lighting operations for $2.8 billion. A year before, Mondelēz International sold its coffee business to JAB Holding Co., pocketing a tidy $5 billion in cash. Several years earlier, BP sold its petrochemicals business for $9 billion in cash — as much as $2 billion more than Wall Street analysts had expected.

In all three cases, the companies weren’t selling distressed or severely underperforming operations. Quite the opposite. They made a strategic decision to jettison parts of their business lines that, while strong, were no longer a key area of focus.

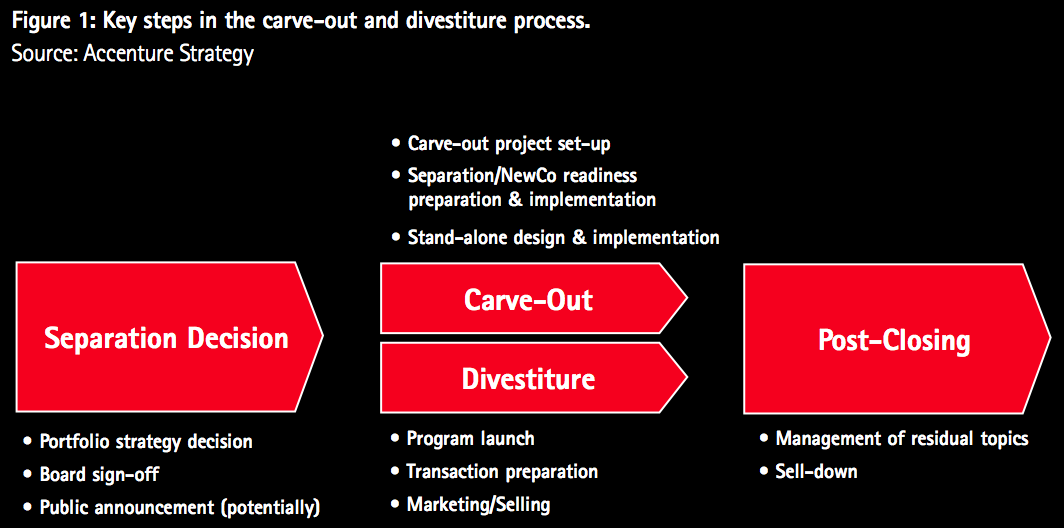

Unfortunately, such moves simply don’t get much attention within many organizations. Too often, companies consider carve-outs only when they feel a part of its business has become too weak or troubled to keep. They get caught up in the more glamorous “buy side” of portfolio building while neglecting the “sell side.” And that’s a huge mistake, which eventually destroys long-term shareholder value. Creating the most robust portfolio possible requires at least as much attention to selling parts of the business that are no longer core as buying new businesses that are deemed a great strategic fit (Figure 1). Worse, because they’ve neglected the sell side, they tend to lack the capabilities necessary to successfully execute carve-outs. The result: They either miss out on opportunities to create significant value, actively destroy value, or both.

The fact is, more companies need to recognize that carve-outs are a key strategic way to enhance their competitiveness by building a portfolio that’s more sharply focused on the strategic intent and the most promising markets and customers.

Selling is just as important as buying

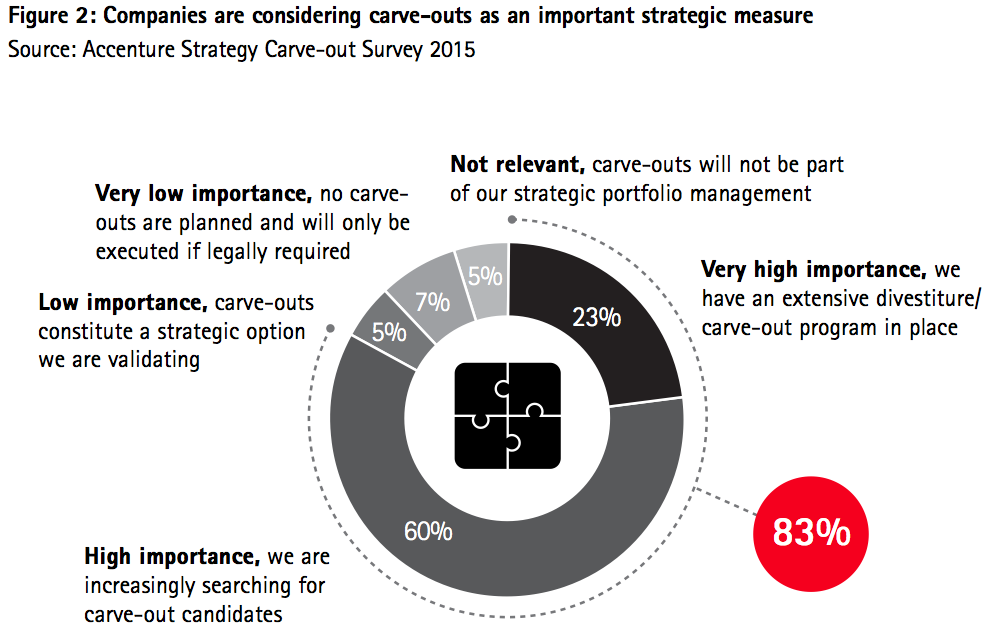

Fortunately, the tide is turning. Executives increasingly understand how important carve-outs are to their company’s ability to compete and to its overall financial health. According to Accenture Strategy research, 83 percent of companies now consider carve-outs to be an important strategic tool to drive competitiveness in the next three to five years.

Why the shift in perspective? The biggest factor is that companies are moving away from the monolithic, large-conglomerate model in favor of developing more entrepreneurial and agile business models to become more responsive to the market. Removing parts of the business that simply no longer fit can play a key role in fostering such agility.

This means being proactive and strategic — not waiting until something goes wrong. Historically, most carve-outs have involved companies shedding business units or lines of business that were no longer profitable or were performing poorly. In other words, there were strong, immediate financial needs to get rid of them. But this approach only invites bargain hunters looking for cheap deals. No one’s going to pay top dollar for a distressed business.

The better route is to routinely assess the portfolio with a strategic eye and sell off non-core parts of the business while they are still performing well and not starved of investments and management attention. Doing so enables a company to get more in return for what it’s selling — money the company can use in more productive ways, such as investing in the growth of their core business.

When it comes to carve-out execution, companies are set up for failure

Despite executives’ newfound appreciation for carve-outs, their organizational capabilities still reflect their company’s historical bias favoring acquisitions: While many have a dedicated M&A and integration function in place, their carve-out capabilities remain significantly underdeveloped. Accenture Strategy research found that only one in two companies have some best practices they apply in carve-out projects, but lack the requisite skills, standard methodologies, and tools required to effectively execute them.

Skills represent perhaps the biggest capabilities gap. Because they lack a formal carve-out function, companies are forced to staff carve-out projects with people who don’t do carve-outs for a living. While they may have solid project managers, they generally don’t have deep carve-out experience. And that’s exacerbated by infrequency: In companies that execute a carve-out only every seven or 10 years, it’s difficult for people to gain that vital experience.

Such capabilities matter—a lot. A carve-out can be an extremely complex project that affects the entire company. It requires a company to make critical portfolio decisions, create the carved-out entity’s operating model, identify which business functions will be affected (and how), and cut all linkages to the parent company — all while minimizing the disruption to the main business.

Companies are putting the value of divestitures at risk

This lack of capabilities can not only inflict long-term strategic damage on the parent company, but also can have a tangible, negative impact on the carve-out project itself.

For instance, without the carve-out experience, a company could end up getting rid of a critical part of the business it didn’t need to or shouldn’t have shed. It also could create a standalone business that in reality can’t function by itself or isn’t particularly valuable to buyers. Or it leaves the parent company with too many stranded costs or liabilities.

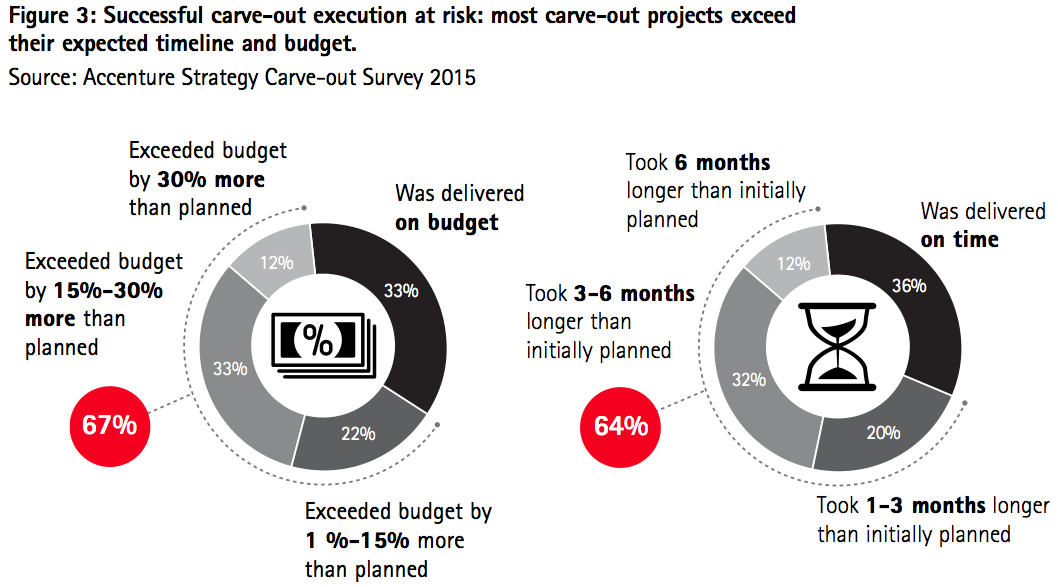

Lack of the right capabilities also can lead to massive delays and budget overruns — something that plagues many carve-out projects (Figure 3). For example, 65 percent of companies surveyed were unable to complete carve-out projects on time, with over 40 percent experiencing delays of more than three months. And 67 percent of companies surveyed couldn’t meet carve-out budgets, with 45 percent exceeding the planned budget by more than 15 percent.

Such poor execution can end up eroding the selling price and increasing costs which, in turn, destroys value and frustrates shareholders.

Only 53%of companies say they have some best practices that they apply, but do not have standard methodologies or tools sets in place.

Six keys to creating more value from carve-outs

There’s no master formula for successfully planning and executing a carve-out. The situation and structure of the parent company, the overall deal structure, and the stakeholders involved make each project unique. However, there are a few common keys that can improve a company’s chances for carve-out success.

1. Define the scope

It’s extremely difficult to do carve-outs right if the company isn’t clear on what it’s pulling out. When determining scope, a company must sharply define the boundaries of the target new company (NewCo) and its future relationship with the parent company — keeping in mind that the parent company must ensure business continuity during and after the project. If the ultimate objective is to sell NewCo, the parent company needs to define NewCo in a way that’s attractive to potential buyers.

2. Articulate a clear direction and get guiding principles in place

Closely related to defining the scope is translating it into a clear direction — i.e., timing and budget, both of which are heavily influenced by the extent to which the target business is embedded in the parent company and the degree of separation expected on Day 1. A high-level road map can help a company develop time and budget estimates. It defines key issues such as the legal structure of NewCo, the parent company’s objectives, the NewCo’s situation and objectives, potential buyers or progress in the sales process, works council negotiations, IT system set-up, and regulatory permits and approval processes. Speed is of the essence in carve-outs: Clear principles help making consistent carve-out decisions on what belongs where. It also helps focusing management on the carve-out “as-is” and not to start green-field sub-projects, which will eventually risk a delay of critical timelines.

3. Set up NewCo for success

Another key is to build NewCo so it can operate efficiently after the carve-out. This requires determining which foundational functions, processes, and infrastructure will transfer from the parent company to NewCo and identifying how to fill any remaining gaps. NewCo should not lack in areas that all companies need to be successful, but it also shouldn’t be weighed down by carrying additional baggage the parent company wants to unload. Ensuring that NewCo is set up to be lean, mean and without cumbersome corporate structures will help the business going forward and, thus, increase valuations.

4. Foster strong NewCo-ParentCo collaboration

The fourth key is to foster strong collaboration between the carved-out business and the parent company to proactively manage different stakeholder interests and minimize conflicts in objectives. In any carve-out, the two entities could have differing perspectives on myriad issues. Among the most common areas are NewCo’s actual boundaries, as well as legal and tax structure; allocation of assets and employees to NewCo; type and duration of transitional services the parent company provides; and the overall project timeline.

An effective way to deal with these potential disputes is to create a single program management function comprising representatives from the parent company and NewCo. Working together, these representatives can account for different objectives, interests and tasks; coordinate the communication process between the two entities to promote a common understanding of the carve-out’s direction and implications; and share information among stakeholders.

5. Close cooperation between deal team and carve-out team

Some critical decisions in the deal team will impact the carve-out and vice versa. For example, decisions on brand, transfer of certain capabilities and provision of TSAs can have serious impacts on timeline and stranded costs. To avoid costly mistakes, close cooperation is mandatory.

6. Support the project with strong carve-out capabilities and governance

The final key is to ensure each carve-out project benefits from the right capabilities. Just as serial acquirers have developed formal M&A capabilities, companies executing carve-outs on a regular basis must develop the appropriate carve-out skills, methodologies, tools and governance within their organization. Carve-outs are massive, complex projects; thus, such capabilities are critical to identifying the right carve-out target and executing the extraction across all functions of that target on time and within budget.

Companies that undertake divestments on an exception basis still need the same capabilities, but they generally don’t have to build a formal in-house function. For these companies, it makes more economic sense to bring in experienced help and not try to complete the projects themselves.

More than ever, a company’s competitiveness is defined by focusing on its core business. Carve-outs are a tool that can help companies gain such focus, but only if they’re executed well. As companies such as Philips, Mondelēz and BP have shown, proactively assessing and fine tuning their portfolios — and selling non-core businesses at the right time and in the right way — can create a lot of value. It’s encouraging that other companies are beginning to embrace this mindset and recognize carve-outs as a strategic tool. Their business competitiveness increasingly depends on it.

Add Your Heading Text Here

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter