Publications Building The Right Organization For Mergers And Acquisitions

- Publications

Building The Right Organization For Mergers And Acquisitions

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Rebecca Doherty, Cristina Ferrer, Eileen Kelly Rinaudo– McKinsey & Company

Support for deal making should be organization-wide.

The internal organization that manages a company’s M&A processes has always been a major contributor to the success of its deals. Today, as companies increasingly choose to manage their M&A processes internally, without the support of financial advisers, it’s all the more important to have the right team in place. This team must not only be skilled at screening acquisition targets, conducting due diligence, and integrating acquired businesses but also have the size, structure, and credibility to influence the rest of the company.

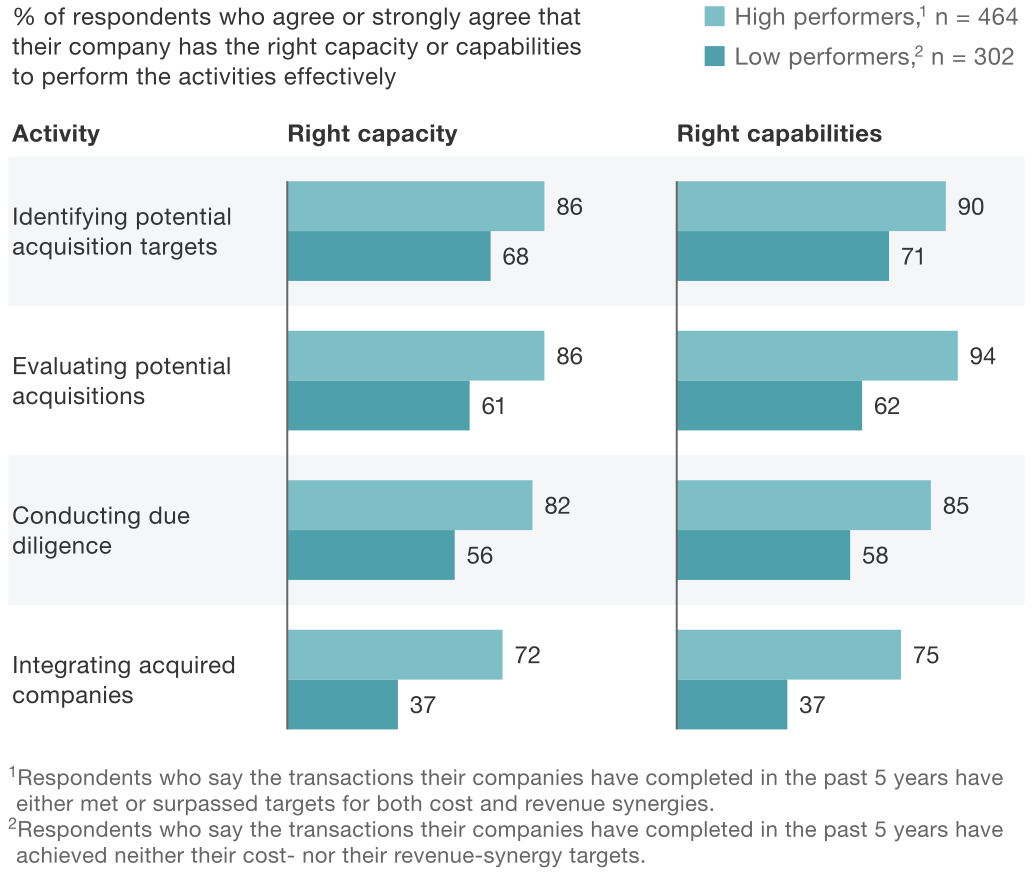

Admittedly, most of the best practices for designing an M&A organization are well known. But, in our experience, many companies fail to put them into practice. M&A teams include members with unnecessary skills as often as they lack members with essential ones. Too little capacity is a common problem, but inflated teams frequently create issues as well. The effect on a company’s ability to capture value from its deals is notable. According to our 2015 survey, high-performing companies are significantly more likely than low-performing ones to report that they have the necessary skills and capacity to support essential predeal activities. Moreover, nearly two-thirds of underperforming companies lack the capabilities to integrate their acquisitions (Exhibit 1).

What best determines the right size and capabilities for your M&A team? We’d highlight three factors: the demands of the M&A program you envision, the type of leadership role the team needs to play, and the relationship it should have with both the corporate center and with individual business units.

Exhibit 1. Companies often lack the organization needed to successfully execute M&A.

Meeting the demands of strategy

An M&A team can best support a company’s deal-making objectives when those objectives flow naturally from a clearly defined corporate and M&A strategy. That strategy establishes the type and number of deals that will need to be closed. That, in turn, establishes a corresponding level of activity and skills needed for the pipeline of potential deals being screened, valued, negotiated, and closed. Companies in fragmented industries with high-volume M&A strategies, for example, will need to screen more deals. In our experience, companies that seek to close 5 to 15 deals a year may need to start out screening as many as 150.

What often happens, though, is that many companies size their M&A teams based only on the capacity and capabilities they expect to need for due diligence. That can lead to a team that is too narrowly focused, that is too tightly staffed, or that lacks essential capabilities to address all deal types or tasks. Because while due diligence is a central piece of the M&A process, it’s not the whole story. Other pieces, such as how large the scan needs to be, the types of companies that need to be screened, and how those companies will be integrated, are equally important when designing the M&A organization.

It’s just as problematic to deploy a team that’s too large and that lacks clear roles and responsibilities or an appropriate breadth of skills. Take, for example, the experience of one global industrial company. When its executives embarked on an ambitious growth program, they quickly agreed that they’d need a bigger, more skilled M&A team to manage the number of deals they envisioned. So they doubled the size of the team, adding employees with experience in their core business areas, and tasked them with a target number of transactions per year. What managers misjudged was the variety of capabilities the team needed to source, evaluate, and integrate different types of deals. Two years later, the company had closed on a fraction of the deals it envisioned — largely due to problems exacerbated by the size of the team, including mismanagement, a lack of strategic focus, and unclear priorities. Many of the deals it had closed seemed to languish. And the M&A team had an 80 percent turnover rate.

A more holistic view of what’s needed to execute an M&A program successfully can identify which skills a team needs, which it already has, and which might be acquired along the way with future deals. Much of this depends on the company’s strategic approach to M&A. Consider the differences for companies using the main approaches to growth through M&A.

Transformational deals don’t require much sourcing effort because they tend to be self-evident and start from the top of the company. They do, however, require an experienced, discreet, and centrally organized M&A team with enough clout to understand and assume responsibility for the decisions it makes. These include, for example, defending the deal rationale, war-gaming the strategy, or even changing the fundamental financial structure of the company. Diligence, while led by this team, requires significant involvement from key functions and businesses. The team eventually grows considerably to handle postdeal integration. At that point, a large deal may need dozens, even hundreds of people from very different areas of the organization, including the M&A team, business units, and support functions, with at least half a dozen fully dedicated to the effort for a full year.

Acquiring adjacent businesses—in new industries or geographies, for example—tends to include a laborious sourcing process to identify appropriate candidates ahead of the due diligence. That often demands a dedicated team with expertise in the adjacent areas to define the attributes of a desirable acquisition target, whether by size, business model, competitive position, economics, or footprint. Integration efforts in this case can vary widely, depending on the degree of integration. Some adjacent acquisitions require larger, more complex integration teams because the value lies in the combination of the operations and activities of both businesses, such as those around R&D. Others require smaller integration teams, for example, when the only goal is to integrate support functions.

At the other end of the spectrum, product and geographic tuck-ins—small acquisitions that fit into a larger existing business—require in-depth knowledge of the product or geographic business. These are typically led by a business unit itself, often alongside the company’s R&D or regional experts. In companies that do several tuck-ins a year, candidates are often on the radar well before an acquisition, and most of the predeal efforts are invested in maintaining valuable sources and developing relationships with potential targets. These companies often have fully dedicated integration managers to run an integration process that is more consistent between deals.

Additional external factors, such as industry fragmentation, major market shifts, and industry complexity, also affect the M&A approach and, ultimately, the skill sets needed within the M&A team. In more fragmented and diverse industries, more effort must be applied to sourcing and initial screening, as candidates might be difficult to identify and public information could be scarce. Team members will need broad experience and a deep understanding of the industry, as well as an ability to quickly review and evaluate opportunities. In turbulent industries where much deal making is under way, teams also need a thorough understanding of the market and the likely response of competitors. And in highly nuanced deals or complex industries, M&A teams should emphasize substantial experience and industry expertise over functional expertise.

In some cases, after considering these factors, companies will realize that they would benefit from a larger standing team to manage the complexity of their upcoming growth. In others, especially in more consolidated industries, where there are fewer strategic M&A opportunities, companies will realize that they’re well served by a small M&A team that takes more of a project-driven approach.

Deciding who should lead

Strategic demands also affect who should lead a company’s M&A program, depending on the nature of the business and the broader industry. In some companies, a corporate M&A unit takes responsibility for sourcing, evaluating, and executing deals connected with the corporate strategy, and the business units are called in to provide subject-matter expertise. This is especially true in financial institutions, where business units have relatively consistent strategic needs. In other companies, business units are responsible for sourcing, evaluating, and executing deals linked to the business-unit strategy, while the corporate M&A unit sets process and valuation standards. Highly diversified industrial groups tend to favor this approach, since it better suits the strategic needs of multiple groups.

Some, especially technology companies, also divide responsibility for M&A between corporate and business-unit leadership depending on the size and type of deal. The business units are responsible for sourcing and integrating deals related to the business-unit strategy, and they lead financial projections and synergy estimations. The corporate M&A unit leads the screening process and valuation. It pressure-tests business-unit assumptions—and also takes the lead on cross-business-unit deals or those that would enter a new adjacent business.

The approach a company takes ultimately depends on how it expects deal making to support specific strategic goals. One technology company, for example, aspires to double in size with a combination of larger deals in its relatively consolidated industry and significant M&A in adjacent spaces. Its corporate M&A group reflects that goal with the two main prongs of its organization: a team with fewer than five people, focused on large opportunities within its industry, and a second team, initially with just two individuals, focused on adjacent business opportunities. The business units themselves do not lead any M&A, though they provide subject-matter expertise during diligence and are heavily involved in and accountable for integration.

Coordinating internal working relationships

As companies confirm their strategy and the role of the corporate M&A team, they must also consider how it will interact with others needed to execute deals. In particular, managers must set clear and consistent expectations of the different organizational groups involved—including an explicit mandate for the M&A team, as well as roles and responsibilities for the corporate-strategy group, interested business units, and key support functions. In our experience, successful acquirers often go even further. They specify how different groups should interact, for example, by requiring quarterly meetings and by defining the inputs and outputs of those meetings.

Without this clarity, a business unit might, for instance, complain that the M&A team kills all its deals while the M&A team complains that the business unit demands due diligence of unviable targets. Such tension and ambiguity can hinder the success of an M&A program. Consider the experience of one large healthcare company. Its highly skilled M&A team suffered from poorly defined roles, tense relationships with business units, and unclear strategic priorities, leading to frustration that undermined the team’s effectiveness. The team lost nearly a third of its members every year for five years—an unexpectedly high turnover rate. Only a substantial push from the executive team to rework the mandate and redefine roles, followed by several months of campaigning with the business units and support teams, was able to reestablish relationships and reset expectations. The underlying organization did not change, but the effort substantially improved the team’s performance and satisfaction.

The working relationship between the strategy group and the M&A team is especially important. High-performing strategy and M&A leaders work together to define how strategic priorities translate into a few targeted M&A themes. The M&A team then ensures that all deals are explicitly linked to those themes—confirming that link during the sourcing, evaluation, and diligence phases to make sure they’re spending time on the right deals as more information becomes available. But given that only 38 percent of high performers in our survey (and 13 percent of low performers) strongly agree that the two groups work well together, it’s clearly an area where most companies could improve (Exhibit 2).

Often, companies combine the two functions or link them within their reporting lines to encourage continual communication. This is particularly common in fast-moving industries, such as high tech or pharmaceuticals. If they are not combined, it is important to orchestrate how the work of each group feeds into the other, such as how the M&A team’s knowledge of what competitors are acquiring informs thinking on competitive strategy.

As companies look to improve how their M&A teams are organized, they must articulate their corporate and M&A strategy, determine how they want the projects to be managed, and enable productive and efficient relationships across the organization.

Exhibit 2. Corporate strategy and M&A groups work better together in high-performing companies.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter