Publications Avoiding the Perils of Traditional Due Diligence

- Publications

Avoiding the Perils of Traditional Due Diligence

- Bea

SHARE:

By Michael May, Patricia Anslinger and Justin Jenk – Accenture

Checking too quickly and focusing too narrowly can be a recipe for disaster. Successful acquirers take a different approach: the disciplined prioritization and organization of a number of fundamental—but often neglected principles. Call it strategic due diligence.

Hewlett-Packard hadn’t been much of a favorite with Sanford C. Bernstein & Company‘s A.M. Sacconaghi. For two years the computer analyst declined to rate the company a “buy.” Then in May he suddenly had a change of heart. How come? Price, for one thing; having dropped nearly 25 percent since the proposed merger with Compaq Computer was announced, HP’s stock looked highly attractive. But Sacconaghi was also clearly impressed by “the enormous and diligent effort” the two companies had put into planning in the pre-deal phase how the combined entity would operate.

If this kind of rigorous analysis can win Wall Street applause for one of the most contentious, high-profile mergers in recent memory, why aren’t more companies doing it?

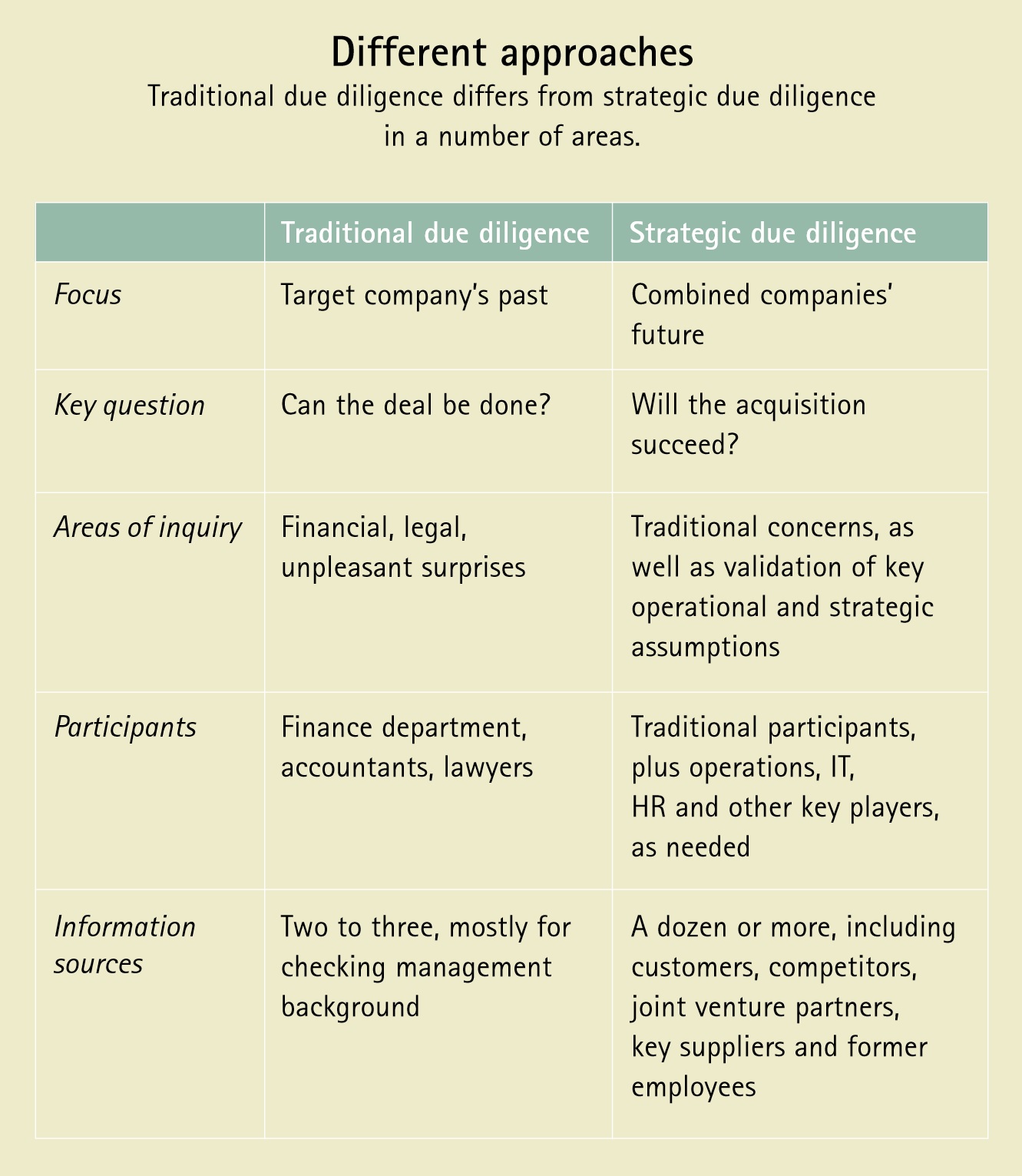

Acquirers routinely perform due diligence. But for a variety of reasons they tend to do their checking too quickly and focus it too narrowly mainly on understanding historical financial reports, uncovering possible legal liabilities and hunting for other unpleasant surprises. In other words, acquirers usually concentrate on the past, not on the future of the combined companies. Traditional due diligence is obviously necessary, but it’s hardly sufficient to ensure a transaction’s long-term success.

The most successful acquirers go far beyond traditional due diligence. They do something best described as strategic due diligence: the disciplined prioritizing and organizing of a number of fundamental but too often neglected principles.

The right price

These successful acquirers look ahead and measure the companies they’re proposing to buy against the strategic vision they want to achieve. They test a whole spectrum of important assumptions, in realms ranging from the more immediate challenges of post-merger integration to the reaction of competitors and the longer-term impact on the industry. How hard will it be to upgrade newly acquired operations to best in class, or to change the incentive system for key managers? Will customers react as hoped? How will competitors respond?

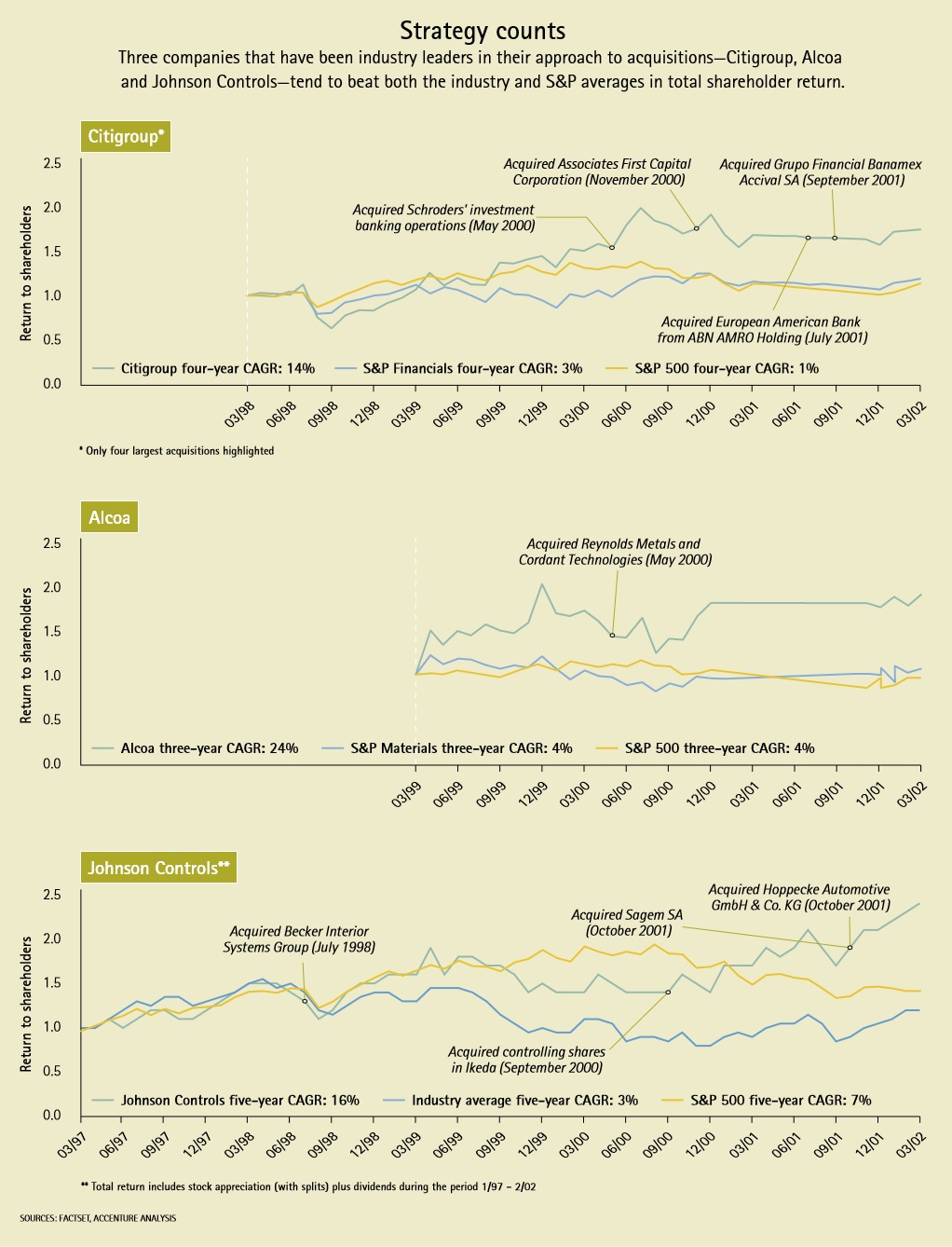

With strategic due diligence built into the transaction process from the outset, the truly successful acquirers are the ones that usually pay the right price for the companies they buy a price that not only reflects the possible net synergies but also takes into account the likelihood that they will be captured. This discipline allows the more successful acquirers to deliver above-average returns to their shareholders.

The majority of acquirers, unfortunately, fall well short of this standard. As study upon study has shown, more than half of all mergers and acquisitions end up destroying value for the companies involved. These failures have produced a growing backlash among shareholders, who are increasingly likely to protest (or simply sell their stock) when a deal is announced. Board members, more keenly aware of their responsibilities than ever, are likewise growing more cautious about M&A. And yet the forces driving companies to merge or acquire globalization, technological change, competition for capital show no signs of abating. The result is a widening gap between the way financial markets treat companies that know how to make acquisitions and the way they treat those that don’t.

We’ve seen this divide open up in various consolidating industries over the past decade, with one or two companies emerging as the master acquirers (and strongest stocks) and the others looking more and more like also-rans. Among the tier-one auto suppliers, for example, Johnson Controls has set the standard for acquisitions. In the aluminum industry, Alcoa stands out as a winner. And in financial services, Citigroup has proven to be especially adept.

Two European-based consumer products companies provide an illuminating contrast. Both have made multiple acquisitions. But from 1996 to 2000, Company A saw the market respond favorably to 80 percent of its biggest deals, whereas Company B got a positive market response to only 33 percent of its acquisitions. The difference in total returns to shareholders in the same period is even starker: 22 percent for Company A, compared with minus 4 percent for Company B.

An obvious question arises. If there is a logical, disciplined process that companies go through to gauge whether a transaction is being properly valued looking at issues such as industry impact, customer reaction, competitor response why aren’t more of them doing it?

View from the top

The answer may lie partly in the dynamic, often top down nature of deal making. When time is short and discretion is important and when the vision comes straight from the top the details of what it will take to make the big picture a reality often go unchallenged and unexamined.

An informal Accenture survey of investment bankers indicates that while acquirers typically spend two to three weeks on the whole due diligence process, a mere three to five days are devoted to strategic issues. And the strategic issues they do investigate are confined to confirming synergies and revising the valuation.

Understanding the target’s financials which are historical and invariably accounting based was considered the most important task by far; validating the reasons to do the deal came near the bottom of the list. In a sense, the purpose of traditional due diligence is simply to confirm that the deal makes near-term financial sense.

The purpose of strategic due diligence, by contrast, is to assess whether the acquisition will succeed, and beyond that, to identify specifically what will need to be done in the post-merger integration to make the transaction a success. Strategic due diligence usually involves a larger cast of players than the traditional variety, and it always makes use of a wider array of information sources.

If strategic due diligence sounds like more work than traditional due diligence, it is. But the best deal makers build teams that know how to run the process efficiently. When deadlines are tight, moreover, the strategic due diligence discipline helps these successful acquirers to focus on some key ideas and assumptions.

Start with strategy

The strategic rationale for an acquisition and the assumptions underlying the acquirer’s valuation are far easier to test if they’re clearly stated. Let’s go back to our European consumer products companies. Company A understood this principle well, but Company B did not. Both wanted to establish leadership positions in key markets around the world. Company A bought leading local brands in its core business, after first making sure that the targets’ marketing, distribution, manufacturing and information technology capabilities fell within an acceptable range.

Company B bought local brands, too, but it often settled for secondary ones, and it was less exacting about their capabilities. Further clouding the picture, Company B made several acquisitions in reaction to transactions made by competitors; these acquisitions were outside its core markets and were not based on meaningful and achievable synergies. Therefore, they created little value.

Involve your top operational professionals early on

Making sure that your target’s distribution or IT system will mesh with yours or that it can at least be improved along the lines you require is not a job for a beginner. Nor is it something you can afford to start addressing late in the merger and acquisition process. Yet in many acquisitions these tasks are tackled often by relatively junior people when the purchase is already well advanced. Not, however, at Company A, which made sure that its top professionals in distribution, IT, marketing, operations and other functions were involved in the pre-deal due diligence process.

The need to listen to employees is most acute for a handful of business-critical functions. It is essential to assess how key managers at your company and at the target company will react to the proposed transaction. Successful acquirers look ahead at how the merged companies will need to operate. A major cause of M&A failure is disruption of the companies’ existing activities.

Gather information from diverse sources

Considering the stakes in most deals, traditional due diligence relies on remarkably few information sources. Only 10 percent of respondents to our informal survey of M&A practitioners said the due diligence process included four or more sources outside the company. Fewer than one-third of respondents said due diligence included interviewing customers of the target company. Yet it’s hard to overemphasize the importance of speaking with those customers who are, after all, one of the major reasons for doing the deal.

The number of external sources contacted during strategic due diligence, by contrast, might be a dozen or more. Besides customers, the list could include competitors and their customers, suppliers, former employees and joint venture partners, among others.

Whether approached formally or informally (as is sometimes necessary), these people can help answer many of the acquirer’s questions. For example: What companies are you likely to give more business to, and why? What are the main obstacles to the target company winning more business? Has the target’s management team had any relatively recent key hires or defections?

Look beyond the obvious synergies

In a traditional assessment of a deal’s benefits, acquirers usually place great emphasis on near-term opportunities for cost savings rather than on revenue enhancement. Given the stock market’s demands for a quick post-deal rise in earnings, perhaps this isn’t so surprising. But the focus on the near term further skews the typical acquirer’s due diligence process which, if it tackles strategic questions at all, will tend to concentrate on relatively low-hanging hanging fruit, such as immediate cost reductions or basic ways to drive revenue. These could include supply chain and operational improvements, a reduction in logistics costs as well as in working capital, and so forth.

On the revenue side, the focus should include adding new distribution channels and geographies, extending the product portfolio and increasing outlays for productive R&D, among other things. These are important value-creation levers, to be sure, and it’s important to test them. But alone, they’re unlikely to make the merged companies a long-term success.

The best acquirers, by contrast, have a strategy that looks beyond the near term, and a due diligence process for testing and supporting that vision. These companies not only test a much broader array of value-creation levers but also examine negative effects the merger might create.

On the positive side, they explore possibilities for defending market share with enhanced or bundled offerings, or for streamlining the business processes and organizational structure of the new, combined entity. On the negative side, the companies worry about the possible loss of revenue from customer defections, the loss of talented employees, an overly complicated organizational structure, competitor reactions and other possible problems.

Strategic due diligence can be best thought of as the way that successful acquirers manage to keep a grand design, and the many structures and factors needed to support it, simultaneously in view. Straightforward in concept, it requires great discipline in practice. The companies that are making it work are looking inward to operations people; outward to customers, competitors, shareholders and regulators; and down the road to the future of the merged companies all at the same time.

But the payoffs of strategic due diligence are commensurately large. For starters, the process screens out some transactions and re-prices others both valuable contributions. The most important effect of strategic due diligence, however, is a simple but profound shift in emphasis from getting deals done to getting them done right. And that increases the chances of the transaction creating value, rather than destroying it.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter