Publications Asia: Time To Refocus

- Publications

Asia: Time To Refocus

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Harvard Business Review, Ernst & Young

Asia: From show me the promise — to show me the money

Companies need a new capital strategy for Asia: one that prioritizes depth in each country rather than breadth of presence across the region. This, the second in a series of briefing papers, discusses how multinational companies should shift from a land-grab strategy in emerging Asia to a focus on profitability.

For two decades, emerging Asia has been a tremendous source of growth for companies. As they invested to tap the avenues of growth the region offered, companies focused on taking territory. But despite revenue growth, profits have proved more elusive.

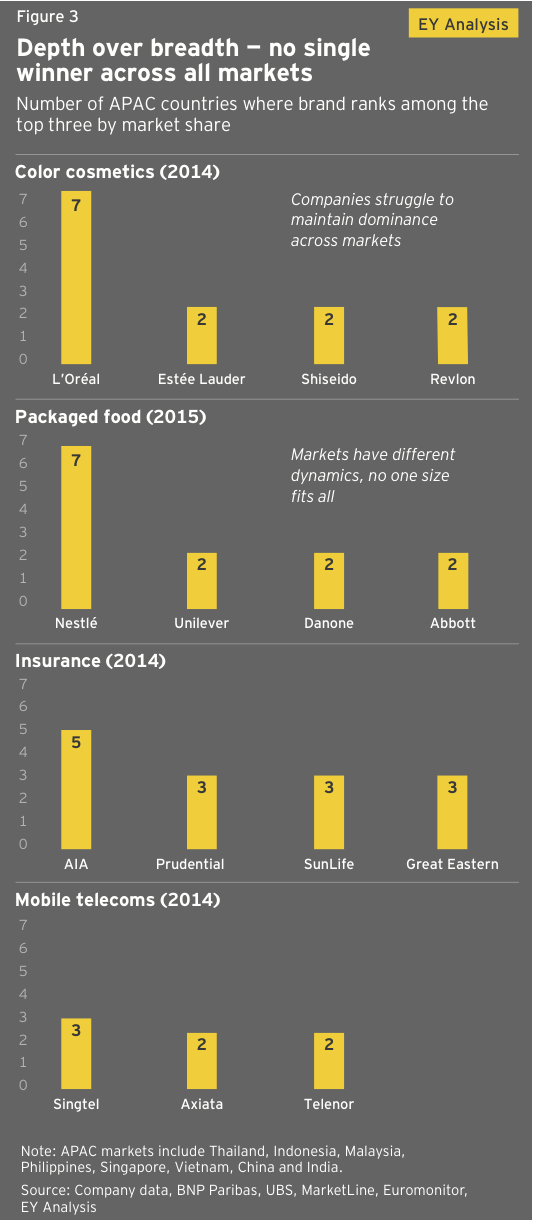

Today, as these economies transform and mature, companies need to aim for market leadership in a country or category rather than widespread but subscale presence. Profitability is closely associated with market-share leadership. The top two or three players capture 60% to 70% of the profit pool — hence, having depth and winning the market share battle are critical.

But for a single company to win everywhere is difficult. Very few companies rank among the top three in market share across all Asia’s emerging countries. This can be explained by varying consumer behaviors, channel landscape, competitive dynamics and country characteristics across markets.

To establish depth, companies will need to:

- Conduct a portfolio review to reassess the company’s ability to achieve market leadership in chosen markets and categories

- Double down in high-priority countries by undertaking transformative deals, including radical mergers and acquisitions, or more flexible partnerships, to lift market share

- Resize go-to-market models, looking at joint ventures, distributors and direct costs

- Reorganize to emphasize country over category

- Launch large-scale cost and organizational transformation to improve profitability

- Plan a path to exit, and limit losses where market leadership and profitability appear difficult

Over the past few years, we at EY have been helping our clients across several industries reconsider their Asia play. We saw a decade or so ago the logic of grabbing land, but the strategy no longer makes sense for companies seeking profit in the region. For companies to stay viable in a newly demanding economic environment, most will need a capital strategy that no longer relies on the promise of growth, but actually delivers on the bottom line.

A capital strategy that focuses on those markets, product categories, and service sectors where they have the best chances of winning. Doing nothing is no longer an option. (Vikram Chakravarty, ASEAN Transaction Advisory Services Leader, EY, Siddharth Pathak, Director, Transaction Advisory Services, EY Singapore)

ASIA: TIME TO REFOCUS

However logical it may have been a decade or so ago, pursuing a land-grab strategy no longer makes sense for multinationals seeking profit in fast-moving Asia.

For two decades, emerging Asia has been a tremendous source of growth for multinational companies and private equity firms. Profits have proved more elusive. Many companies have struggled to adapt their products and services in line with diverging local tastes, to establish the right go-to-market models, to contend with surprisingly formidable local competitors, and to negotiate the region’s complex business environment. Still, many have stayed the course, convinced of the need to stake their claim in a region whose growth potential once seemed almost limitless.

Now, with Asia growing far more slowly than it was a decade ago, that approach is no longer sustainable. Companies that were betting on runaway growth need to rethink the Asia story and embrace a new capital strategy focused on depth—market leadership in a country (and/or category)—over breadth. Rather than trying to compete in every geographic market, product line, or service sector, often at subscale levels, they need to double down on those core areas where they are already doing well, invest judiciously in subpar performers where they can identify a plausible path to profitability, and exit businesses or markets where profitability prospects remain poor.

SHOW ME THE PROMISE: HOW WE GOT HERE

Standing at the threshold of the 21st century, the promise of another Asian miracle was palpable. In the 1950s and 1960s, Japan had shaken off the destruction of World War II to transform itself into the second-largest economy in the world. Over the ensuing two decades, the four Asian Tigers—Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan—largely replicated Japan’s miracle, morphing into highly developed economies that became home to world-class companies and vast new ranks of increasingly affluent middle-class consumers. As the 1990s got under way, China and its neighbors in Southeast Asia appeared poised to repeat the magic as their economies grew at two, three, even five times the pace of developed markets.

The response from multinational corporations and private equity firms was predictable and not entirely unreasonable. They flocked to China and India, and in many cases to the smaller Southeast Asian countries of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Their unabashed goal: establish beachheads across the region, and gain first-mover advantage. If profits weren’t immediately on the horizon, the reasoning went, they soon would be.

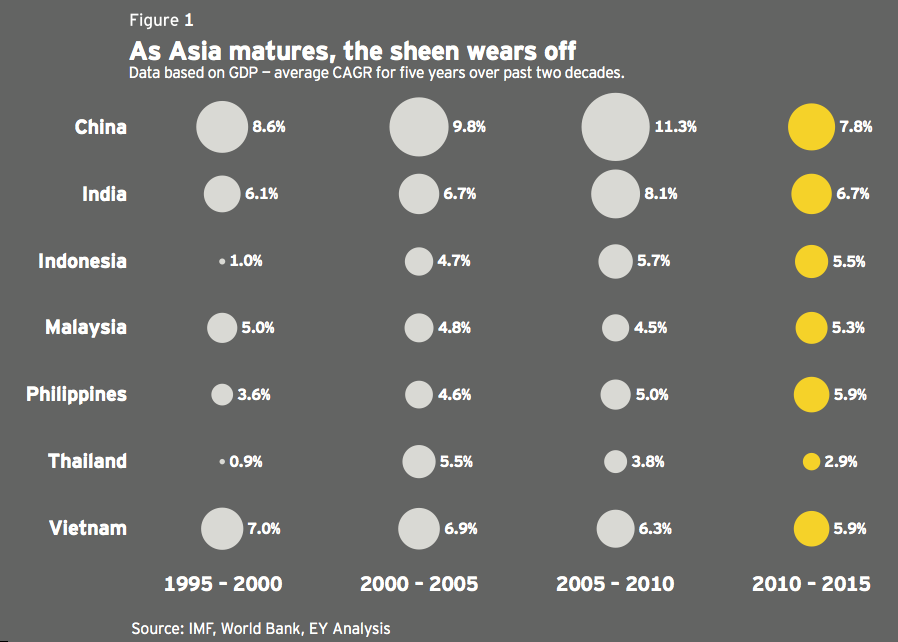

ASIA SLOWS

For a while, this worked—for some companies, in some markets. But today the land-grab strategy that drove much of the foreign investment in emerging Asia over the past two decades has played out. As the region has evolved and matured, growth has slowed, and competition from both local and multinational players has intensified. High levels of debt, weak and volatile currencies, slow progress on economic reforms, and, in some countries, corruption and political instability are impediments to better performance. Plunging commodities prices, linked largely to China’s pullback on infrastructure spending, also are weighing on the region. Capital flows are shifting in search of more promising opportunities elsewhere.

China, which is undergoing a structural shift from a capital-driven economy to a consumption-led economy, is the biggest player in this story, not only because it is by far the largest Asian economy but also because the degree to which its growth trajectory has moderated is most dramatic. From 2003 through 2010, China’s economy grew at an average annual pace of 11 percent. In 2015, it grew 6.9 percent. After years of government-financed spending on infrastructure, it now has a glut of everything from steel and manufacturing capacity to housing stock—and debt, which rose to a record 237 percent of the country’s gross domestic product in the first quarter. Investors worry that China’s slowing growth could pressure economies not just in Asia but around the globe, signs of which are already evident.

BUT ASIA IS STILL RELEVANT

The picture isn’t entirely dismal, of course. In fact, far from it. Even at last year’s slower growth rates, Asia accounted for approximately two-thirds of the 3.1 percent growth in global gross domestic product. And when China’s $10 trillion economy expanded by “only” 6.9 percent in 2015, the gain was bigger, in absolute terms, than the one recorded 10 years earlier when the country’s then $1.7 trillion economy grew by 11.4 percent.

In the meantime, Asia’s burgeoning middle class continues to grow. By 2030, according to an estimate from the OECD Development Center, the ranks of the middle class across all of Asia, including emerging and developed markets, will exceed three billion people, or nearly 10 times the current population of the United States. By then, Asia will account for 66 percent of the world’s middle class, up from 28 percent in 2009. As the disposable income available to this expanding middle class continues to grow, corporations will have tremendous opportunities to further penetrate the Asia market, where consumption of many goods—from breakfast cereals to analgesics—remains far below the levels common in developed markets.

“Our view of the region continues to be very, very positive,” says Amit Banati, Singapore-based president of the Asia-Pacific business for breakfast and snack food company Kellogg Company, which has been operating in the Asian marketplace for over five decades. “Yes, in the short term we have foreign exchange volatility and GDP growth going down. And at times like this, you may have to adjust your tactics. If things get tough, if currencies are volatile, you do the normal stuff—adjusting prices, managing costs, maybe dialing down a little bit in terms of investment. But we see this as part of a business cycle. Most of the companies in this part of the world are positioning themselves for sustained multidecade growth, and our overall strategy at Kellogg is certainly being guided by the long-term dynamics.”

“Emerging Asia is evolving from a world in which the major economies are largely manufacturing-based to one in which they will be largely consumer-based,” says Ming Lu, co-head of Asia for private equity firm KKR & Co. LP, which has extensive holdings in Asia. “In the very long term, emerging Asia will remain the key global growth engine.”

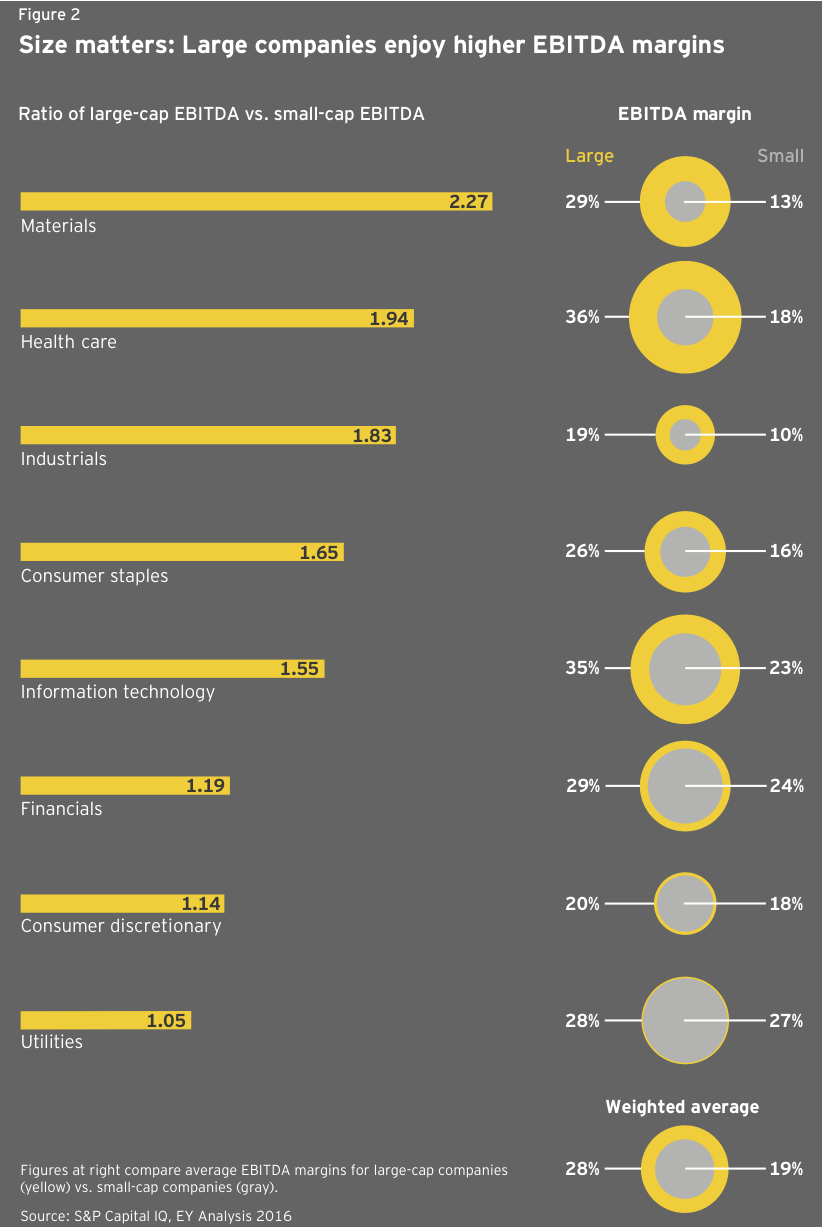

SHOW ME THE MONEY: SCALE MATTERS

But for companies to capitalize on that promise—to stay viable in a newly demanding economic environment—most will need a capital strategy that focuses on those markets, product categories, and service sectors where they have the best chances of winning. Often, that will mean those where they are among the top three in terms of market share.

Why focus on market share? Scale matters. History and economics show that the top two or three market-share leaders in a given business typically capture about two-thirds of the available profits. That doesn’t mean no company can succeed with modest market share, or that market share alone ensures success. Still, “in most businesses, scale correlates positively with profitability,” says Lu. “That’s particularly true for businesses that require a substantial capital investment and intense marketing. In fact, scalability is one of the key criteria we use at KKR to evaluate our investment opportunities.”

“Our view is that scale really drives profitability,” agrees Kellogg’s Banati.

MARKET SHARE INCREASE: GETTING HARDER

But scalability of the sort we’re discussing here—translating success in a company’s home market, or in one or two offshore markets, into profitability across an entire, diverse region like Asia—can be extraordinarily challenging. For most companies, a one-size-fits-all approach to doing business won’t fly. Winning the market-share battle requires tailoring products to meet local demands, tastes, and local shopping habits.

“A lot of companies, once they come up with a successful product or business proposition for mature Western markets, tend to blindly roll it out worldwide to emerging markets,” observes Anup Chib, who spent 10 years as a senior executive in Asia-Pac for pharmaceutical and consumer health care company GlaxoSmithKline plc. “That can be a recipe for disaster.”

Adapting entrenched products to local tastes—or developing new products from scratch for local markets—can require a substantial investment not only in research and development but also in identifying, hiring, and nurturing local managerial talent who understand local market conditions. Multinationals that fail to take these steps often end up losing not only to their peers that avoid these pitfalls, but also to local competitors that have a visceral understanding of their market and their customers, may be willing to operate at lower profit margins, and seldom seek to compete across the entire region. India’s persistently profitable supermarket chain D-Mart is a prime example. It is thriving under measured growth strategy, while foreign competitors continue to operate at a loss or have simply left the country. Indeed, says Lu, “Many Asia-based companies are winning the ground war over multinationals in sector after sector in emerging Asia.”

“When you are out there battling competition that includes both multinational corporations and regional and local companies, you are fighting with a different set of rules,” says Pradeep Pant, former president of Asia-Pacific and EEMA with Mondelez International. “Some are different not only in terms of compliance but also in terms of how those different competitors define profitability, which can put a ceiling on pricing. This is the cross a lot of multinationals have had to bear.”

To further illustrate how hard it can be to win the market-share battle on a broad front, consider the top six packaged-foods companies operating in the five original countries in ASEAN—Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore—plus Vietnam. Last year, as measured by market share, only one company—Nestlé—ranked in the top three in a majority of those markets. None of the others had a top-tier market share in more than two countries.

“There will almost always be some markets and categories where you won’t have the right to win,” observes Chib. “There will be someone else who has first-mover advantage, scale, a superior supply chain, better margins, and a greater ability to unlock that opportunity. You have to decide if you can build the necessary capabilities to win. If you can’t, then you have to exit.”

DEPTH OVER BREADTH

All this makes it imperative that multinationals and private equity investors focus on depth before breadth. Country or category depth is simply critical to dominating trade, especially in emerging markets where considerable business continues to be done under traditional models, and where channel penetration is such a significant driver of consumer sales. Consider the traditional sari-sari store in the Philippines or the Kirana store in India, carrying limited brands of a single product. Competitors with scale can win shelf space in those stores by working with the strongest distributors, investing more in advertising and promotion, and having a stronger sales force and better-organized sales and supply chains.

Companies with a subscale presence find it difficult and expensive to compete, making profits elusive. The problem is exaggerated when a company tries to maintain a subscale presence across multiple markets.

THE CHALLENGE: RIGHT TO WIN

Buying into the depth-over-breadth argument, of course, isn’t the same as executing on it. The challenge for multinationals begins with figuring out exactly how and where they should focus their capital and other resources, and where they should fall back. Emerging Asia is not a monolith. Political models, regulatory regimes, cultural norms, consumer behaviors, and distribution channels vary from one country to the next, as does the maturity of each country’s infrastructure. Regions or markets inhospitable to some businesses are still attractive to others. Right now, China continues to offer tremendous growth opportunities in some areas—food safety, quality health care, e-commerce—whilst others continue to stall, like steel, cement, coal, and construction equipment, all of which are suffering from overcapacity. “If you are in one of the consumer-focused or service-focused sectors, particularly serving the middle class, you can still be growing very fast,” says Lu.

Even Kellogg, which operates in virtually every corner of Asia, is mindful of the changes the region is going through. While the company hasn’t withdrawn from any markets, it is prioritizing where it’s committing its capital. Its focus is on markets with great depth.

“The way we assess the depth of a market is by the size of the opportunity and our right to win in that market,” Banati explains. “Assessing your right to win requires that you assess the opportunity from multiple angles: the capabilities of your management team, your relative market share, your margins, your profitability, your route to market. We think carefully about where we can create a model that gives us the right to win.”

Under this approach, Kellogg prioritizes large markets where the company has strong brands, strong leadership, and a strong distribution network. It treats as export or “make available” markets those that don’t offer a right to win, meaning it makes its products available, but selectively. Banati cites Indonesia as an example. Kellogg has also partnered with organizations that could give it the resources it needs to compete more deeply, much as it did in Nigeria in 2015 when it announced a partnership with Tolaram Africa, one of that country’s largest food companies.

EXECUTING A DEPTH-OVER-BREADTH CAPITAL STRATEGY

Although a number of companies have begun transitioning to a depth-over-breadth capital strategy in Asia, it sometimes has been done on a reactionary basis—a response to external events or pressure from shareholders or activist investors—rather than a deep analysis of their business. Companies seeking a more measured approach can find it in the following steps:

• Conduct a portfolio review, reassessing the company’s ability to achieve market leadership and profitability in each of the countries and categories in which it competes. Look at what drives growth in a given market or category, the size of the opportunity, and the company’s ability to address the growth drivers in the highest-value markets.

• Double down in priority countries by undertaking transformative deals—big-bang M&A transactions and partnerships—to boost market share quickly. While there’s nothing wrong with organic growth, tweaking products, pricing, cost structures, and go-to-market strategies in a bid to boost revenues and profits organically can be slow going, and harder to execute when unsustainable in a market where general economic growth is slowing and competition is stronger. Mergers and acquisitions bring their own challenges, but, done right, mergers, acquisitions, and joint ventures can catapult a company into the top three by market share quickly. This can be transformative. In 2012, Kellogg acquired the Pringles potato chip business from Procter & Gamble, giving it instant entrée into the snack food business, which is approximately 10 times larger than the breakfast category in Asia. “It gave us scale,” Banati states.

• Right-size go-to-market models. Depending on their scale, category and channel configurations, and strategic visions, companies should right-size their go-to-market models. Among the factors to be considered—all with a hard eye on market reality—are the impact on fixed costs and margins, the company’s sales and distribution capabilities, its scale within distribution channels, its ability to find a reliable go-to-market partner, and governance and control issues.

• Launch a large-scale cost-cutting initiative to improve profitability. Companies exiting or entering markets in Asia may need to revisit their cost structure to jump-start a path to profitability. Under land-grab strategies premised on extraordinary growth, many companies established Asian operations with excess fat across the organization, including manufacturing, and throughout the supply chain. Some also entered into suboptimal agreements with external parties—third-party manufacturers or marketing agencies. An honest and critical zero-based budgeting exercise is needed.

• Reorganize to emphasize country over category. Multinational companies with subscale operations across categories may find it helpful to take a country rather than category approach to competing in Asia. A category approach can work well when categories are large and distribution channels mature, as they are in the West. But in emerging Asia, volumes in individual categories are often small. Accordingly, companies may find it easier to achieve scale in sales and distribution across a range of categories within a single country rather than across a single category.

• Plan a path to exit, and limit losses, where market leadership and profit-ability are not realistic. There’s no pleasant way to exit a losing business. In some cases, companies simply need to swallow their medicine—shut down operations, write off the investment, and move on. Where this is the case, companies should establish a dedicated divestiture team and be prepared to offer stakeholders a valid plan for redeploying any capital released by the retrenchment in order to make the exit as seamless and cost-effective as possible.

“When you are out there battling competition that includes both multinational corporations and regional and local companies, you are fighting with a different set of rules.” – Pradeep Pant, Former President of Asia-Pacific and EEMA, Mondelez International

THE UPSHOT

Asia today is not the emerging Asia of 20 years ago, or 10 years ago, or even five years ago. It continues to grow faster than most developed economies, but more slowly than it did in the past. It remains a region of great opportunity, but also one where profitability remains elusive for those unwilling to invest the resources necessary to tailor their offerings and business models to its individual markets. Companies that have yet to see Asia’s promise cascade to the bottom line must determine where they have a path to profitability and focus their attention there. Depth, not breadth, will win the day.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter