Publications Alliances For Competitive Advantage: Why, When, And How

- Publications

Alliances For Competitive Advantage: Why, When, And How

- Bea

SHARE:

By John L. Forbis, James A. Finnegan – Arthur D. Little

For better or worse, alliance formation soared during the 1980s as corporations united for competitive advantage. While many alliances have been highly successful, others have ended bitterly, and some should never have been formed in the first place. In today’s world, it is important to understand when an alliance is an appropriate investment vehicle and when it is not; it is equally important to understand how to form an alliance properly.

The Why and When of Alliances

The „why and when“ of alliance formation depends on recognition of the differences among a corporation’s businesses and the appropriate investment strategies for them. During the 1980s, conglomerates largely unraveled and other corporations restructured to focus on a few „core“ businesses – businesses with strong competitive positions, well-established product lines, and excellent management teams. Core businesses exclude marginal businesses and opportunistic investments. The core businesses of the Campbell Soup Company, for example, include both Campbell’s soups and Pepperidge Farm baked goods; however, Campbell’s wholly owned Win Schuler Foods subsidiary, a $20 million snack food manufacturer, would not be a core business. Core businesses come in two varieties: first, what we call „foundation“ businesses, and second, businesses that are vigorous but not vital to the overall success or sustainability of the company.

Foundation Businesses. Foundation businesses „are“ the corporation. Examples include automobiles and trucks for Germany’s Daimler-Benz and consumer electronics for Japan’s Sony. Corporations may have other significant business interests that are not foundation businesses, such as aircraft manufacturing for Daimler-Benz or movie theaters for Sony. Foundation businesses are strongly linked to the corporation’s profit objective and have clear synergies with other businesses within the corporation. Typically, a foundation business is worth most to the corporation that owns it.

Wholly owned, direct investments – rather than alliances – are ultimately best for foundation businesses. This is particularly true for short-term, or „current,“ investments. One of the primary goals for a foundation business is to maintain its strong competitive position; thus, management generally wants to build a wall around the business to protect the key secrets to its success. However, alliances present a high risk that competitive secrets will leak out. For years, U.S. manufacturers pioneered consumer electronics technologies, many of which were transferred to Asian manufacturers. By focusing on short-term incremental profits rather than long-term market opportunities, U.S. manufacturers effectively gave away the U.S. consumer electronics market to foreigners. Zenith, for example, is the last major U.S. television manufacturer.

A second goal is continuous improvement of the economics of the foundation business. Few corporations can tolerate a foundation business that earns 25 percent on capital when it could be earning 35 percent and still maintaining its competitive position. While there are some counter-examples, in our experience a wholly owned, direct investment can provide far better operating performance than is typically available within an alliance. In general, it is easier to share operating skills and process knowledge within a corporation than across the borders of an alliance.

Finally, the corporation is going to be very dependent on the foundation business in the long term. Wholly owned, direct investments improve sustainability and reduce risks more than alliances, where a mismatch could jeopardize some aspect of the foundation business’s long-term future. The ill-fated AT&T/Olivetti alliance hurt the foundation businesses of both companies, as neither was successful in marketing the other’s products overseas.

In some instances, alliances can be appropriate for foundation businesses. Long-term, or „long-cycle,“ investment strategies for foundation businesses are essential for positioning the corporation for the future and for sustaining profitability and growth. Alliances are often needed for expansion, providing the corporation with quick access to new and emerging technologies, new geographic areas, and/or new types of customers. For example:

• Merck, the ethical drug giant, allied with Immulogic Pharmaceutical, a start-up, to develop drugs for auto-immune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

• Hewlett-Packard entered the Japanese electronics market through an alliance with Yokogawa Denki, a Tokyo electronics manufacturer.

However, at some point the alliance should probably become wholly owned. Both Merck and Hewlett-Packard have increasing equity positions in their alliance partners. Today’s long-cycle investments will become tomorrow’s current investments, at which point the corporation should recognize the advantages of wholly owned, direct investments over alliances.

Which brings us to the subject of dissolving alliances. When an alliance becomes a current investment in a foundation business, it is time to convert it to a wholly owned, direct investment. It is vitally important that both partners understand the incremental economics of the business and that the process of dissolving alliances is just as important as the process of forming them. At the time the alliance is formed, the process for dissolving it should be established. The process should allow the foundation business owner to exercise the option to buy within a certain period while protecting the value of the alliance. If a „game plan“ is established at the outset, ill will should be minimized.

Vigorous But Nonvital Businesses. Almost all corporations have vigorous but nonvital businesses that coexist with the foundation businesses. British Petroleum’s foundation businesses are based on petroleum and chemicals, while BP Nutrition and Purina Mills, manufacturers of animal feeds, are vigorous but nonvital businesses. Such enterprises are generally close to free-standing businesses and are usually worth more to another corporation, where greater synergies would be available. One company’s vigorous but nonvital business is another company’s foundation business. For example, BP Nutrition and Purina Mills might be very attractive to ConAgra. Outsiders, over time, usually become the ultimate owners of investments in the business and often of the business itself (you would not expect BP Nutrition and Purina Mills to remain wholly owned subsidiaries of British Petroleum forever).

Alliances usually provide the most sensible current and long-cycle investment strategy for vigorous but nonvital businesses. Because the corporation’s commitment to a nonvital business is substantially less than to a foundation business, alliances provide greater flexibility.

For current investments, alliances may allow the corporation to make trade-offs among competitive position, improved economics, and reduced risk. Alliances also help the corporation exit the business if it suddenly faces a daunting obstacle (e.g., a major technological hurdle). GTE is leaving the long-distance telephone service business by placing its Sprint communications subsidiary in an alliance with United Telecommunications and then selling its interest in the alliance to United Telecommunications. At this point, GTE owns less than 20 percent of Sprint.

For long-cycle investments, alliances provide a low-cost opportunity to exploit long-term trends. Their main investment emphasis, however, is on maximizing short-term profitability through synergies between partners. You may have the market access while your partner has the technology – how do you combine the two? General Motors (GM) wanted to be a leader in applying robotics to automobile manufacturing. Lacking robotic technology, GM formed an alliance with Japan’s Fanuc Ltd. The alliance, GMF Robotics Corp., created and exploited the trend toward automated automotive manufacturing. It became the world’s largest robot maker, satisfying GM’s needs as well as those of other automobile manufacturers, such as Ford and Mercedes-Benz.

In sum, alliances can be a valid strategy for making interim investments in foundation businesses or investing in vigorous but nonvital businesses – provided each alliance is formed and managed correctly.

How to Make Alliances Work

Forming an alliance is much like Thomas Edison’s definition of an invention: 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration. Conceiving an alliance – imagining the potential, anticipating the sharing of resources, skills, strengths, synergies – is the 1 percent inspiration. Dealing with a difficult negotiating partner – ironing out differences in personality and perspective, and actually translating the visions into realities – is the 99 percent perspiration. Successful alliance formation requires a 100 percent effort: inspiration to define the structure of the alliance (its organization, strategy, goals, and ownership), and perspiration to survive the process (consensus formation, partner evaluation, partner selection, and negotiations).

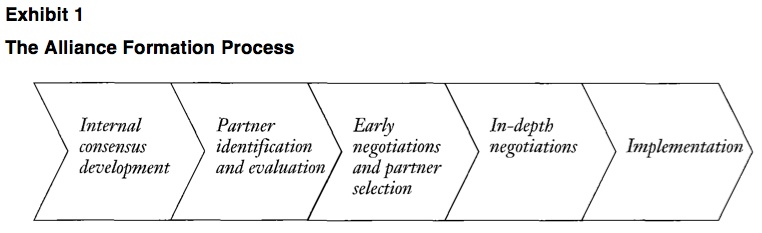

Exhibit 1 illustrates alliance formation as a five-step process. Briefly, these are:

• Internal consensus development: Why pursue an alliance?

• Partner identification and evaluation: With whom can we ally ourselves – and how?

• Early negotiations and partner selection: How can we cooperate?

• In-depth negotiations: Should we conclude a deal?

• Implementation: Can we translate our vision into reality?

Internal Consensus Development. The purpose of this first step is to document exactly why you are pursuing an alliance. A white paper should be developed and circulated within your organization. It formally explains your logic. It will also play a very important role as you get into the difficult stage of trying to muddle through the confusing aspects of merging businesses. It acts as a kind of touchstone – a „sanity check“ – to keep you in sight of your goals.

The white paper should clearly state the purpose of the alliance in the form of concise objectives for all organizational entities involved. A corporate objective might be to gain access to an emerging technology for its foundation business by funding another company’s R&D efforts, while a business unit objective might be to advance commercialization of the technology. Defining the objectives will also help identify the internal concerns about the alliance and the steps necessary to resolve them.

The white paper should also identify the minimal success criteria: the goals the alliance must achieve to be minimally successful, as well as the sacrosanct corporate assets that cannot be incorporated, involved, or violated. Not all criteria are financial. For example, a Scandinavian company with a strongly employee-welfare-oriented culture developed the following inviolate rules to guide alliance formation:

• No employee would be forced to join the alliance.

• No job would be lost because of the alliance.

• Any partner must share the company’s values and policies toward employee welfare and rights.

Similarly, an innovative chemical company with a broad patent position in advanced materials set the following minimal success criteria. First, the partner would provide a strong entree for marketing its new products to Japanese automotive companies, both in Japan and at overseas locations. Second, the partner would guarantee the provision of the products’ key raw materials to ensure a superior cost position after the advanced material patents expired.

The effort placed on consensus development will better your likelihood of success further down the road. At all costs, avoid the „ready, fire, aim“ syndrome. Contacting companies before your goals are cast in concrete will leave you in a weak negotiating position.

Partner Identification and Evaluation. This second step in the alliance-formation process answers the question: With whom can we ally ourselves – and how? The goal is to identify two to four companies that appear to satisfy your alliance objectives.

Myriad techniques and analytical methods can be used for evaluating potential partners. At this stage, the company should be more concerned with broad issues than with the details.

Regardless of how you undertake this analysis, it is helpful to look at three broad strategic parameters. The first is „competitive impact“ – the types and degrees of mutual advantage gained by forming an alliance with a particular partner. The second parameter is „fit“ – how well the businesses complement each other, in terms of facilities, cultures, products, and skills. The third parameter is „balance“ – what each partner will contribute to the alliance. Understanding these resources and assets helps to define ownership and control issues, initial negotiating positions, and the potential partner’s basic interest in the alliance.

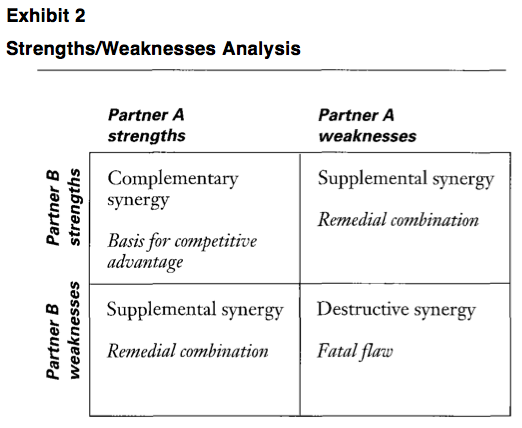

As background for evaluating these parameters, we recommend conducting a „strengths and weaknesses analysis“ based on the full range of key success factors that would be relevant to the proposed alliance (e.g., product development, technical service, sales force training). You should evaluate your own company and each potential partner vis-a-vis these success factors. By noting your respective positions for each factor on a matrix, you can quickly determine the types and sources of synergy inherent in a proposed alliance with a particular partner.

Exhibit 2 illustrates such a matrix. The ideal situation is essentially a „strength-to-strength“ alliance – such as the Daimler-Benz/Mitsubishi alliance in aircraft manufacturing – combining the strengths of both partners to create complementary synergies and a true basis for competitive advantage. Supplemental, or remedial, synergies – the root of most alliances – offset one partner’s weakness with the other partner’s strengths. This is a good clue to the balance issue, demonstrating which company is really bringing how much to the alliance. Weakness-to- weakness combinations should probably be cause for eliminating a potential partner. The AT&T/Olivetti fiasco has been attributed to irreconcilable differences generated by a telephone equipment maker and a computer concern representing each other’s products. AT&T now has an alliance with a much more compatible partner: Italtel.

Early Negotiations and Partner Selection. Once a company has identified two to four promising candidates, it is time to contact these companies and undertake the early negotiations that lead to partner selection. You should talk to three or four companies simultaneously. In the process, some prospects always fall out.

In some cases, they may all fall out. So, spread your risk by talking to a number of companies in parallel. We see this as a three-phase series of contacts with each potential partner.

Intelligence Meetings. These are usually mid-level contacts designed to test the water without arousing a great deal of attention or excitement. The goal is to convince the contact to champion the alliance internally, promoting it and identifying the key decision-makers necessary to bless the deal.

Chemistry Meetings. These are typically senior-level contacts, where the two CEOs determine whether they can agree on the fundamental mission and scope of the alliance and whether their personalities would allow them to work together. During this phase, if all goes well, the CEOs should decide on a schedule for the next phase, and each should designate a team leader to represent the company.

Preliminary Bargaining Meetings. The objective of the preliminary bargaining meetings is to select a partner from the two to four candidates you have contacted. Fundamentally, your decision should be based on which potential partner:

• Is serious about the proposed alliance

• Offers the best likelihood of an attractive and practicable deal

• Is most likely to provide the best combination of competitive impact, fit, and balance

This phase also gives you the opportunity to reassess your commitment to the alliance strategy. It is not too late to abandon the quest and pursue an alternative strategic action, such as merging the business, acquiring a company, or licensing technology.

In-depth Negotiations. Once you have selected a partner, you can draw up a memorandum of understanding and begin in-depth negotiations. The memorandum documents the results agreed on during the preliminary bargaining sessions: the concept of the alliance and its scope, objectives, and limitations. The memorandum is key to helping maintain focus and momentum throughout the in-depth negotiations.

You should subsequently form a joint study team composed of business unit and corporate representatives from both sides. The objective is to translate the memorandum of understanding into a legal and binding bargaining agreement for a strategic alliance. Often, the resolution of some minor issues can be deferred until implementation, based on the good faith and good will of both sides.

Implementation. The objective of implementation is to translate the legal bargaining agreement into a legal entity – an established alliance. This is primarily a series of financial, legal, and organizational actions designed to resolve the minor issues, fulfill the required governmental filings, and establish operations. Interestingly, even before operations actually begin, the alliance often assumes a life of its own, negotiating for itself not only with outside suppliers but with both partners as well. The vision has finally become reality.

NUMMI: A Classically Formed Alliance

New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI), the General Motors/Toyota alliance, illustrates the alliance-formation process.

Internal Consensus Development. Toyota approached the 1980s having made the strategic decision to produce automobiles in the United States. An alliance would help the company learn the ropes (e.g., the North American labor market, negotiations with the United Auto Workers, the North American parts supply market) before investing in wholly owned operations.

Partner Identification and Evaluation. Of the three major U.S. manufacturers, Chrysler was struggling to survive, so Toyota focused its investigation on Ford and General Motors.

Early Negotiations and Partner Selection. In 1981, preliminary intelligence meetings took place between Toyota and Ford and, later, Toyota and General Motors. After the discussions with Ford reached an impasse, talks blossomed between Toyota and GM. By the end of the year, Mr. Toyoda and Mr. Smith held their chemistry meetings to discuss the mission and scope of the proposed alliance. By the spring of 1982, preliminary bargaining meetings were held and initial commitments were made.

In-depth Negotiations. Toyota and GM reached a bargaining agreement in just 11 months – an amazing feat, considering the complexity of the deal and the vastly different corporate cultures involved. But both Mr. Toyoda and Mr. Smith were highly committed to making the alliance happen. Both saw dramatic benefits: Toyota would learn about North American production at relatively low risk, and GM would learn Japanese management techniques.

Implementation. The road to implementation was bumpy. Chrysler sued to block the alliance as collusive. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) carefully evaluated the deal – embarrassing Toyota with its demands for sensitive information (e.g., costs, profits). Finally, a consent decree was signed with the FTC, and NUMMI was legally formed in February 1984. But there were more roadblocks. The Fremont, California, plant had to be reopened. Workers had to be hired. A management structure had to be installed, and a new labor contract had to be established with the United Auto Workers. Altogether, it was 39 months from the preliminary intelligence meetings in October 1981 until the first car rolled off the assembly line in December 1984.

Parting Thoughts

Investments in Foundation Businesses. To help sustain the corporation’s earnings and growth, current and long-cycle investments in foundation businesses should almost always be wholly owned and direct. When IBM entered the computer business in the 1950s and 1960s, it did not have the necessary expertise in technology, manufacturing, marketing, or selling. IBM could have followed the alliance route but did not, electing to develop its own technology, manufacturing capability, marketing programs, and selling skills. The effort took several years, but was clearly worthwhile. Similarly, IBM transferred its development and marketing expertise to wholly owned subsidiaries in Japan and Europe.

The improper use of alliances in foundation businesses can cause nightmares. As current investments, alliances can sacrifice the profit potential and sustainability of the corporation. U.S.-based Norton Company, for example, established a worldwide network of alliances during the 1980s. Unfortunately, Norton was not able to realize the profit potential (and create value) from these alliances. Norton recently rejected an offer from the United Kingdom’s BTR PLC and agreed to be taken over by France’s Compagnie de Saint-Gobain.

Failure to convert alliances to wholly owned, long-cycle investments can often jeopardize competitive advantage and full profit potential. Shareholders expect management to exploit fully the profit potential of any key technology investment rather than compromising the profit stream with an alliance.

Should you find yourself with unwanted alliances in a foundation business, plan to buy out your partner, recognizing that you will probably pay a premium, since the alliance is far more valuable to you as a wholly owned investment in your foundation business than it is to anyone else.

Investments in Nonvital Businesses. Alliances are almost always the best way for a company to invest in its vigorous but nonvital businesses. Alliances allow you to act quickly either to invest or to withdraw from the business as circumstances dictate.

In contrast, wholly owned direct investments in non-vital businesses can create a disproportionate commitment to the business. Such investments also encumber cash that could be invested more profitably in the foundation business. Finally, they consume an enormous amount of corporate energy and time that should be directed toward reinforcing and strengthening the foundation business. When Richard Ferris was chief executive of Allegis (née UAL/United Air Lines), his strategy was to create a broad-based travel empire that included United Airlines, Westin Hotels, Hertz car rentals, and Hilton International Hotels. Most of Wall Street was unimpressed with this strategy. Many investors felt that Ferris was investing far too heavily in his vigorous but nonvital peripheral businesses and depriving his foundation airline business of the investment it needed to maintain its premier position. Investor pressures eventually forced Allegis to remove Ferris and refocus the company. The nonairline portions were sold off, and UAL Corporation was reborn.

Thus, alliances are the best investment strategy for non-vital businesses. But what if you find yourself with a „bad“ alliance? The process of dissolving an alliance is largely the reverse of the formation process discussed earlier. The principal issues involve competitive impact, fit, and balance – but from a buyer’s perspective. However, if the process of alliance formation has been judiciously followed, the chances of a „bad“ alliance should be minimal.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter