Publications Achieving Post-Merger Integration

- Publications

Achieving Post-Merger Integration

- Bea

SHARE:

By Evelyn Bourke, Gillian Laidlaw, Ian Woods – Towers Perrin

What does it take to ensure a smooth transition following a merger or an acquisition? A survey of UK insurers reveals the capabilities needed for successful integration.

What are the key requirements for successful integration following a merger or an acquisition? A study of predominately UK life insurance companies that had gone through some form of merger or acquisition during the past five years offers some clear answers. Although the study focused on post-merger integration, it explored the complete life cycle of an M&A deal, from strategy formulation through post-merger integration. The study consisted of personal interviews with executives directly involved in the operation.

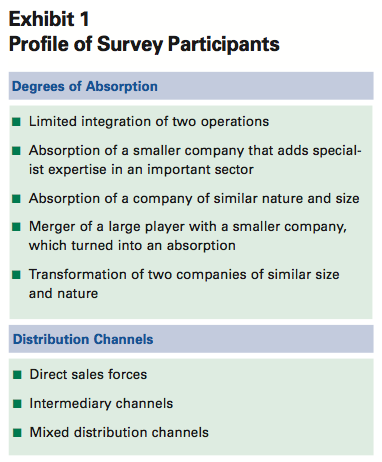

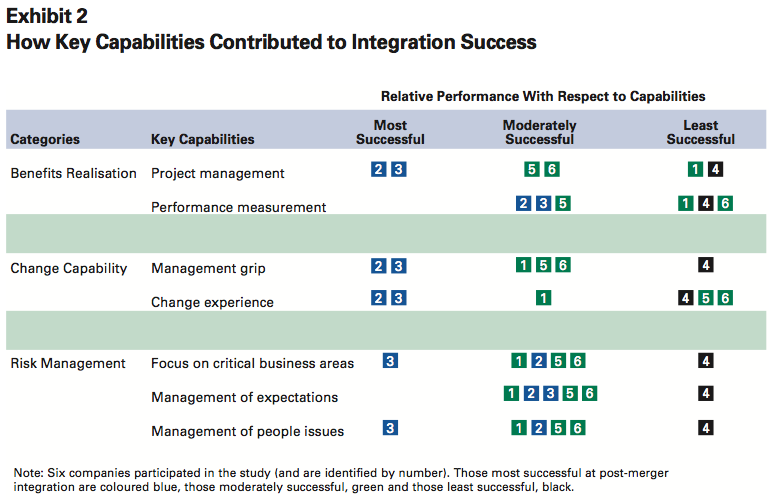

The insurers participating in the study differed widely and had experienced varying degrees of integration success. (See Exhibit 1.) Particularly successful companies had common capabilities, which have been summarised and organised into a three-part model. The headings “benefits realisation”, “change capability” and “risk management” encapsulate these three sets of capabilities. (See Exhibit 2.) Exhibit 3 lists the criteria for evaluating participants based on these categories.

Realising M&A Benefits

The organisations most successful in achieving the anticipated benefits of the merger or acquisition had all placed a high value on project management and performance measurement.

■ Project Management. The stronger performers set and adhered to a tight time frame, understood that speed was critical and recognised the danger of being internally focused for too long. They also knew the importance of aligning project approach with the degree of integration necessary. Thus, a large, complex integration required very substantial planning before implementation. The larger projects typically entailed a formal phase of intensive analysis and design.

The selection, organisation and work style of the integration team largely determined how the team fared with planning and analysis. Effective teamwork, and the balance of power and influence within the group, shaped general opinion on both sides about who really dominated. During times of uncertainty, as in a merger or an acquisition, employees scrutinise management actions to anticipate what might be in store for them and to judge the credibility of the messages being communicated.

The management of the lead organisation must identify at the outset all of the strengths of the acquired company and decide which of them it wants to retain. The discovery of previously unrecognised strengths during the integration process could distract it from its main integration aims. Revisiting and reappraising previous decisions will slow the process and risk undermining the integration effort.

After the planning phase, the quality of the hand-over from the integration team to the line had a major impact on both the ownership of the integration initiatives and the success of the implementation. Delays and failure to meet deadlines inevitably occur when hand-overs are badly managed (e.g., with unclear accountability and lack of commitment to targets).

Most companies acknowledged that they had underestimated the huge demands the exercise put on their HR functions. HR resources were typically stretched to their limits at the time of greatest demand. Organisations need contingency plans for bringing in outside help.

Finally, the most successful companies had taken a pragmatic approach. The need for speedy action precludes spending time seeking ideal results. Pursuing a hard-to-achieve 95% solution over an easier 80% solution does not pay off.

■ Performance Measurement. The companies that accomplished the smoothest integrations had developed detailed pictures of desired end states (i.e., what the organisation would look like after six months, 12 months and two years). They had clear conceptions of the organisation’s structure, product range, systems and distribution channels at key intervals. This is particularly important when there are large numbers of employees who need to buy into these goals. The end state pictures were typically outputs from the design and analysis effort.

Along with these targets, management must have a strong performance measurement and tracking system in place. Such a system should include both quantitative and qualitative measures of performance. To monitor progress effectively, an organisation must dedicate sufficient resources to the task — an easily overlooked factor. During the integration period, resistance or push back will inevitably occur. A strong measurement and tracking system, based on a thorough and credible design effort, is essential for containing and managing resistance.

Managing the Change Process

The companies that achieved the most efficient transitions had found ways to manage the M&A process while maintaining business as usual. They exercised the appropriate amount of management control, or “grip”, and had the ability to learn from experience.

■ Management Grip. Getting the post-merger management team to work together effectively is crucial to achieving the required degree of management grip. Divisions among management can undermine the whole exercise. Because leadership is so vital, the CEO must ascertain whether managers are truly committed to the goals or are merely paying lip service. Ground rules on acceptable behaviour are needed — and must be enforced. The leaders have to make decisions quickly and adhere to them.

To work together effectively, the management team must be clear on the precise objectives of the integration. Because management grip can be undermined by taking on too much change, the number of change initiatives taking place at the same time as integration needs to be reviewed. Some initiatives may have to be postponed. Management must take a tough line on what is really needed — and when.

Finally, accountability is the defining quality of management grip. Integration requires real commitment, and CEOs should be wary of assuming that it exists. Assigning ownership for the integration on functional grounds may seem logical, but it can leave important interdepartmental processes in limbo. Common areas of inadequately defined accountability in these circumstances are communications and management information.

■ Learning From Experience. Most organisations have been through some form of major change in their histories. The more successful ones try to learn from their experiences and apply the lessons appropriately. A post-project review should always conclude such a process, as well as specific means of capturing and disseminating the learning.

Organisations have different change histories. Therefore, the degree of change targeted in the course of the integration exercise should reflect a company’s particular history and capability for change.

Managing the Risks

The best organisations had identified and managed the most important risks inherent in the merger or acquisition. They paid careful attention to key areas of business performance, employee perceptions and expectations, and other people issues.

■ Attention to Critical Business Areas. Not all corporate functions are affected similarly or are subject to the same risk of destabilisation. Weak implementation has a greater impact on business performance for some functions than for others. Therefore, management must identify high-risk areas and make sure they receive the necessary attention. Some areas are obvious (e.g., distribution channels). Others are less so (e.g., management information systems, which can experience extreme stress if two product ranges are being merged).

Distribution channels may require individualised treatment. For example, a self-employed direct sales force (DSF), with loosely defined operating territories, will have different issues from a broker sales force, where each salesperson focuses on clearly defined panels of brokers. Merging the latter inevitably produces some losers (e.g., due to smaller or nonreducible panels). Merging self-employed DSFs may lead to fewer or smaller threats of redundancy or retrenchment but demands a quick buy-in by sales managers. If disgruntled, these managers can move a team to another company quite rapidly.

■ Management of Perceptions and Expectations. Site closings emerged as a particularly thorny issue. Most companies had overestimated how many employees would voluntarily relocate as a result of the closure. The loss of a site and of large numbers of personnel can have major consequences. For example, when one of two sites is closed, the culture of the open site will prevail. Also, if the organisation’s aim is to have a “best-of-both” merger or a “merger of equals”, large staff losses can compromise the plan.

In many mergers or acquisitions, management starts with the goal of retaining the best of both from the two organisations. Achieving this goal, however, is not easy. How do you assess fairly two similar candidates competing for the same job? What may seem pragmatic to management may not be acceptable to staff, and this best-of-both goal can create unrealistic or unmeetable expectations. Adopting such a policy requires careful consideration. The alternative may be to state explicitly that there is a dominant party, that not all positions will be open and that some decisions cannot be made based on best-of-both principles.

Once the complex task of integration gets under way, both organisations need to consider how the outside world will judge success and plan either to achieve the results anticipated by the stock market or to change the expectations. Failure to do so could undermine the credibility of the management team.

■ Management of People Issues. Staff generally regard a merger or an acquisition as a threat, initiating a period of uncertainty. Under- estimating the stress people experience is easy to do and risks poor morale. Management must reduce the uncertainty with strong, clear communications from the outset. Even if the news is bad, it is better to relay it than to delay it.

Most companies in the study acknowledged that their messages had been insufficient and that not enough resources had been used to confirm and reinforce them. Communications is a thankless task. As far as one’s internal audience is concerned, it will never be completely right. However, with frequent communications — even when there is no new message — management will retain control of the process. There is no substitute for face-to-face communications. Furthermore, managers will seem more in control if they are perceived to be communicating ahead of events.

A merger or an acquisition is a time of great stress and anxiety at all levels in the organisa- tion. It begins with the initial announcement and continues as the full impact of the decision becomes apparent and the integration unfolds. During this period, individual managers are likely to get less direction and encouragement than usual (because their supervisors are also extremely busy). Yet this is a time when sup- port is most needed and companies may have to take special measures to compensate.

A merger creates a major disruption in the life of an organisation. The sheer enormity of the effort can overwhelm a business. Companies that plan effectively, manage the process carefully and communicate directly to reduce employee uncertainty will have a greater chance of achieving a smooth integration. It is vital to move forward from the merger as quickly as possible to build a new future.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter