Publications A New Playing Field: The Emergence Of Pan-European Retail Banks Through Cross-Border M&A

- Publications

A New Playing Field: The Emergence Of Pan-European Retail Banks Through Cross-Border M&A

- Bea

SHARE:

Creating global champions

By Deloitte

Executive summary

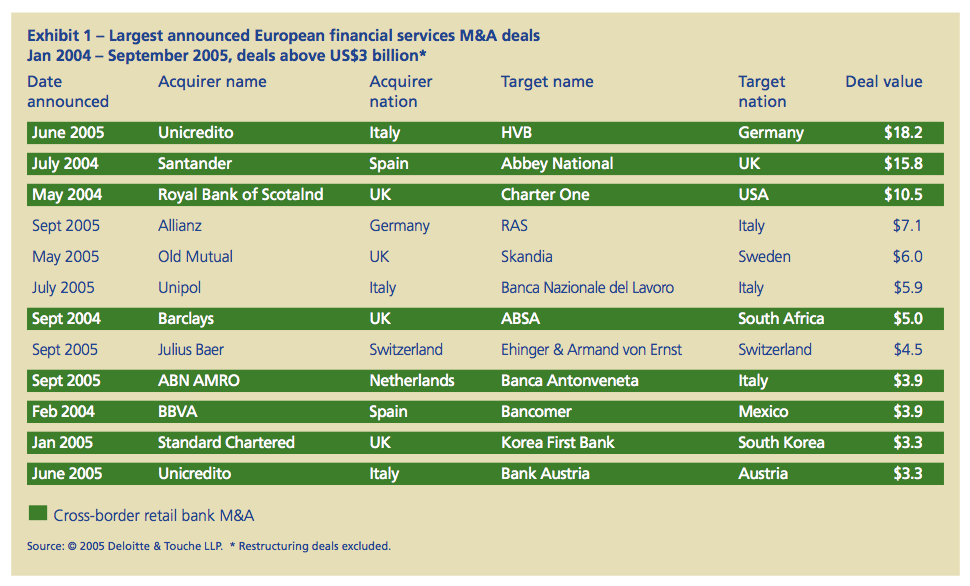

1) Cross-border retail banking boom underway. In the past two years, eight of the 12 financial services mergers above $3 billion (USD), with a European domiciled firm as the acquirer, have been cross-border retail banking transactions. As the European banking market enters new and previously uncharted waters – the completion of large-scale, cross-border, retail banking mergers – the question of whether this is an anomaly or the start of a longer-term trend takes on increasing urgency. Although annual predictions of an impending surge in retail banking cross-border mergers have often come to nothing, we have reason to believe that we have actually begun the long anticipated cross-border consolidation process. To date, cross-border banking deals have been constrained by perceptions of hostility from consumers and regulators, combined with more promising in-market growth and value creation opportunities for most banks. For reasons listed below, we believe this is changing.

2) Political, cultural barriers to pan-European mergers and acquisitions (M&A) eroding. The unspoken understanding that national bank regulators would work to frustrate the acquisitive ambitions of non-domestic banks is fast fading. The fact that cross-border retail banking deals in Italy, Germany and the UK have all been completed in the past 15 months indicates an openness among the continent’s biggest economies that was only dreamt of in the past. This recent trend toward increased openness is given even more force as the EU’s commissioner for internal markets continues the investigation into financial services merger barriers following the Bank of Italy’s involvement in the recent acquisition of Banca Antonveneta by the Dutch bank, ABN AMRO. These political trends become more potent when commingled with the evidence of an increased willingness on the part of consumers to purchase financial services products from non-domestic institutions. Retail bank consumers’ openness to ‘foreign’ banks is evidenced in small ways, such as the rebadging of Barclays’ Spanish subsidiary, Banco Zaragozano, as Barclays, and is being propelled by gaping price discrepancies across different domestic markets for identical baskets of retail banking services. Taken together, we see cross-border banking mergers gathering momentum as the previously deal-breaking forces of political and cultural resistance crumble, even if tax differences persist.

3) Bank executives searching for double-digit growth. Most bank CEOs are hard pressed to find organic growth opportunities of sufficient size to please investors’ profit growth demands. With most banks having undergone massive restructuring to strip out costs and continually scouring their operations for additional savings, the only real routes are through mergers or radical organic expansion in the range of activities into investment banking, private banking or insurance, or some combination of these. Most domestic markets, however, are too concentrated to allow a large competitor to bid for another major player. This leaves cross-border M&A as the most likely outlet for executives’ growth ambitions.

“…we have reason to believe that we have actually begun the long anticipated European retail banking cross- border consolidation process which, if it follows the US path, could result in hundreds of European banks disappearing.”

4) Market participants scrambling for supremacy. Playing the cross-border merger game will require banks to stake out new banking territory aggressively. However, banks face a very real check on their ambitions in the form of their newly assertive institutional shareholders as evidenced by some recent deals that have been undercut by shareholders unconvinced of the deals fundamentals – for example, Deutsche Borse’s bid for the London Stock Exchange. In order to gain the consent of shareholders to engage in cross-border mergers, banks need to demonstrate the following: experience working across borders and cultures; skill in seamlessly integrating acquisitions; clearly articulated plans regarding how value will be created; regional operating and IT platforms that work.

5) US banking experience provides an outline of future European consolidation. While we recognise the dangers of drawing conclusions from the US experience, given cultural and political differences, the fact is that the United States is the only other large, fragmented banking market that has undergone massive consolidation. Using simple comparative economic analysis, and the fact that the US market began consolidating earlier than did the EU, it is possible to get a glimpse of the future by looking across the ocean. What we see in the US market are a few very large, transcontinental retail banks – Bank of America, Wells Fargo, JP Morgan Chase, etc – competing with a variety of more traditional medium-sized and local banks and specialists. We believe that the European banking market will develop along similar lines with a few retail behemoths serving consumers across the entirety of the continent, while medium-sized and local banks, along with specialist providers continue to thrive in their niches. Additionally, the eventual winners in the banking consolidation game are those that get big quickly by buying large, established banks in new markets, integrating quickly and repeating the process. Equally important, however, is to execute each merger flawlessly so that the bank’s overall market capitalisation rises in line with the asset base.

Predictions and recent events

More than five years after the introduction of the Euro on 1 January 1999 and 16 years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, cross-border retail banking mergers are finally beginning to create pan-European financial services institutions. Although we have seen the emergence of pan-European corporate banking competitors in investment banking, syndicated loans and investment management, following previous sector specific consolidation, cross-border consolidation in retail financial services has not yet happened. Indeed, Chief Executives have found acquiring branch networks across borders a far more daunting prospect – that is until now.

We anticipate that by 2010 a handful of retail financial services firms will operate across the breadth and length of Europe. These institutions will have world-class scale and efficiency and while large components will be built organically, they will be created through cross-border mergers – the opening round of which is already in motion. If US trends are anything to go by, hundreds of European banks will disappear in the next five years.

“We anticipate that by 2010 a handful of retail financial services firms will operate across the breadth and length of Europe.”

The prime driver of consolidation is the pressing need to generate earnings growth in an environment where organic growth is hard to come by; economies of scale are now more realisable too. Although this desire for growth is tempered by the mixed shareholder value creation record of retail banking deals, there is a dawning realisation among investors that highly efficient, operationally sound banks have a tremendous opportunity to ‘roll-up’ poor performers in other countries via cross-border M&A. Of equal importance with the economic drivers behind these pan-European deals are the eroding barriers to cross-border financial services mergers. Indeed, political opposition to non-domestic acquirers is retreating as the European Commission actively seeks to break down national barriers to consolidation and European consumers are much more open to purchasing products and services from non-domestic institutions.

This confluence of increasing economic pressure and eroding barriers is resulting in a surge of cross-border retail merger activity in financial services. After many years of surprisingly few deals, the pace of cross-border retail/universal banking mergers has recently accelerated. Over the past 21 months, from the beginning of 2004 through the third quarter of 2005, eight of the 12 acquisitions of $3 billion or more by European financial services firms have been cross-border retail banking deals, as shown in Exhibit 1. These broader economic forces, coupled with the recent surge in deals lead us to conclude that these recent acquisitions actually mark the start of a gathering trend toward the birth of pan-European retail financial services providers.

Earning the right to play

In order to undertake a cross-border merger and acquisition strategy, financial institution executives need to gain the blessing of their newly assertive shareholders. A number of financial services institutions now have highly efficient operating platforms, with cost/income ratios of 50% or lower, which they can introduce to the institutions they acquire, leading to considerable savings. The ‘efficiency gap’ between these institutions and the least efficient is now considerable, creating a number of cross-border acquisition opportunities. Many have proven records for integrating acquisitions, either domestically, in the European market, or outside of the EU and still others have won the confidence of shareholders through years of careful stewardship and consistent profitability. Only those institutions which have some combination of efficient operations, a track record of successful consolidation, or experience working across borders can earn the right to participate in the coming consolidation. In contrast, private equity houses are embarking on transactional deals, designed to buy individual business lines or assets, strip costs or create scale and capture gains through a further sale or from more efficient operations.

But cross-border mergers do not make sense in all areas of retail financial services. While skilled acquirers can extract scale-related synergies from banking businesses with branch networks and relatively straightforward products such as deposits, credit cards, mortgages and mutual funds, there are fewer easy synergies to be had in the more complex product areas such as life assurance.

For life assurance companies, national personal tax regimes and strikingly dissimilar savings habits in different countries mean that it is harder to identify and realise efficiencies from pan-European mergers. Similarly, we do not expect a wave of pan-European mergers among general insurance companies, although we may see some strategic acquisitions where they make sense.

Indeed, we believe that a current lack of profitability and looming capital issues will first spur continued domestic rationalisation in both of these sectors, possibly being followed by cross-border deals.

Looking forward, the number of financial services mergers in Europe is unlikely to match 1999’s peak, but the scale of the cross-border deals underway, and on the horizon, means the total value of M&A activity should approach 1999’s levels, with a handful of large banks carrying out sizeable mergers. The process of pan-European consolidation will be intermittent, as an institution makes an acquisition, integrates it, and then makes the next acquisition.

The need to fully integrate and ‘digest’ each new acquisition explains why the current consolidation period will stretch out over a period that could be as long as five years.

Finally, these deals will likely all take the form of outright acquisitions, rather than mergers of equals, given the difficulty of creating value without a single partner in charge. As noted by Abbey CEO, Francisco Gómez-Roldán at the Fitch Ratings global banking conference in London this summer, “We don’t believe in (mergers of equals). They are defensive in nature and unlikely to create value.” But there were “Darwinistic selective acquisitions” that had the potential to create value under certain conditions and the Abbey purchase fell into this category, he said. From the buyer’s perspective, Mr Gómez-Roldán said, there must be a clear retail business model to export, transferable IT systems and spare management capacity.

UK building societies

Twin challenges arising from cross-border M&A

Since building societies are mutually owned, and therefore outside the reach of traditional merger and acquisition activity, most industry commentators downplay the impact that broad cross-border consolidation activity will have on building societies. However, just because building societies apparently fall outside the cross hairs of acquisitive competitors doesn’t mean this broader trend will bypass building societies completely. Instead, we see two strategic implications for building society executives arising from pan-European banking consolidation:

• An opportunity to seize customers while competitors are distracted

While the rest of the industry’s executives are focused on being hunters, not prey, building societies have the opportunity to make significant inroads into the high street bank’s existing customer bases. building societies often enjoy greater trust with retail customers and, in many instances offer more cost competitive products. Focused marketing effort to target the customers of rival banks as, and when, they are embroiled in a deal will be a critical determinant of growth.

• A need for greater efficiency

The large High Street banks are actively seeking scale economies in their internal operations. Increasing M&A activity will push average costs lower across the industry as inefficient competitors are driven from the business. This, in turn, will put pressure on building societies to reach for ever greater efficiencies to allow them to continue to offer low cost, value for money products to their members. While many building societies will adapt to the cost pressures by sharing certain services to gain efficiencies, it is likely that some will be unable to respond adequately to the intense competitive pressures to reduce costs.

Outlook

We believe that there may well be acquisitions in this sector, with the financially stronger building societies seen as the natural winners attracting some of the weaker ones once the ‘hearts and minds’ of executives are won over and assurances can be provided that their members will be protected.

Consolidation: the path ahead

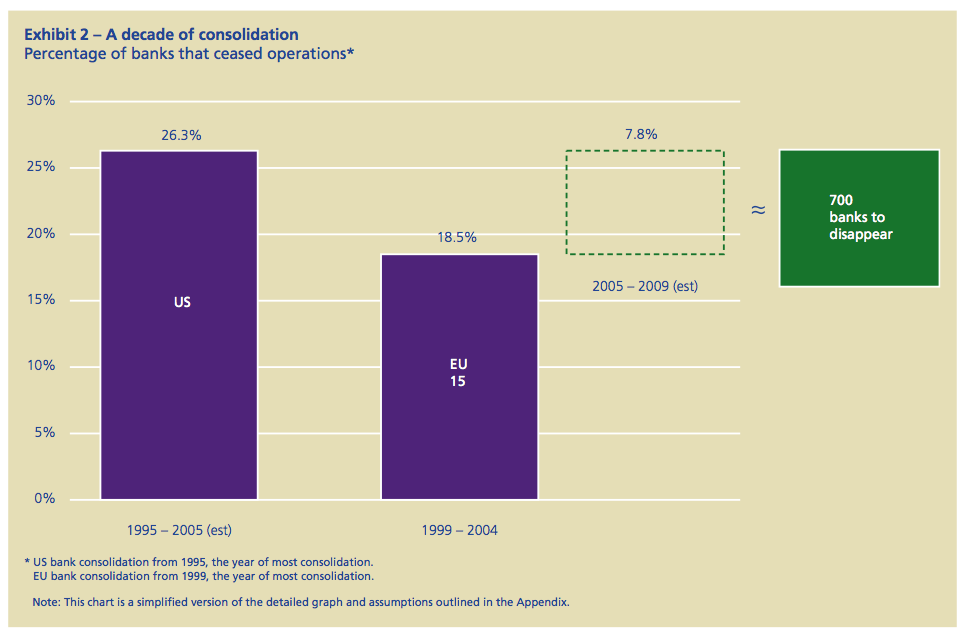

When considering what the path of financial services consolidation will look like across the coming years, it is useful to look to other large, fragmented banking markets and understand the lessons to be drawn from their experience. In this case, the only market comparable to the EU is the United States, where interstate banking mergers have already created some of the world’s largest pan-continental financial services groups. Both the European and the United States banking industries have a similar history – fragmented banking markets with long-standing historical legal restrictions on inter-state mergers. Looking at the United States across the past two decades we see that bank consolidation activity reached a high water mark in 1995, when furious competition among local and regional banks led to 5% of the banks in operation at the start of 1995 to cease to exist at the end of that year. This initial phase of increasing economies of scale and achieving the easy synergies from rationalising overlapping branch networks created a number of powerful regional banks, but it was not until around 2000 that we began to see the outlines of the ‘endgame’ – the emergence of truly national retail banking giants that spanned the entirety of the United States.

Europe has a heterogeneous set of national interests and cultures in comparison to the much more culturally homogenous United States; this cultural barrier, coupled with differing legal, tax and regulatory frameworks has, so far, hindered pan-European consolidation although there have been significant transactions such as HSBC’s acquisition of Crédit Commercial de France in 2000 or Barclays’ takeover of Spain’s Zaragozano in 2003, and Banco Santander acquiring UK’s Abbey in 2004. Additionally, within Scandinavia there was significant merger and acquisition activity and consolidation.

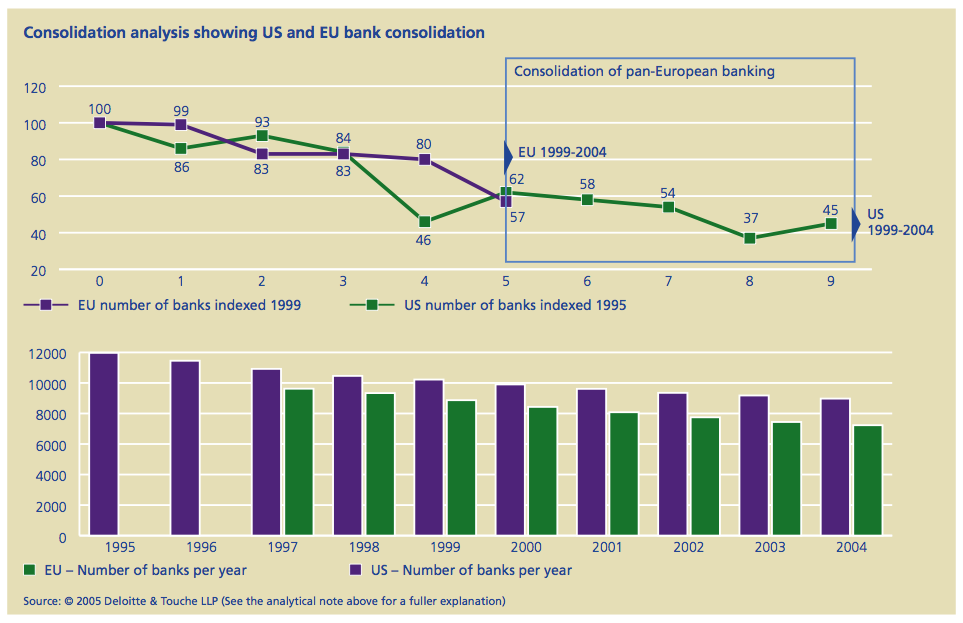

As different EU markets continue to harmonise their legal systems and as product nationalism fades, we believe that economic arguments will increasingly drive consolidation, just as happened in the United States. To learn from the US experience and to help us better predict the way forward, we analysed banking consolidation across the past 20 years. Mapping the number of mergers in the United States and Europe shows the two set on remarkably similar paths. We found the year of the most intense merger activity – 1995 in the US and 1999 in the EU – and then by overlaying Europe’s banking market onto the US trends we estimated European consolidation going forward, as shown in Exhibit 2. That analysis shows the two markets consolidating at a remarkably similar rate and allows us to make some early predictions. Looking at the US experience from its peak consolidation period in 1995, we can see that it took about five years for mergers to start creating retail banking giants with pan-US operations. If large market consolidation follows a similar pattern, which the data appear to support, 2004/2005 time period is when we are witnessing the creation of pan-European financial services giants; eg Santander/Abbey, Unicredito/HVB, ABN/Antonveneta.

If history continues to be our guide, we would expect Europe’s path of consolidation broadly to mirror that of the United States. Indeed, this analysis, along with the other factors discussed above, is what underpins our belief that we are present at the creation of truly pan-European retail banks; today, we are witnessing the opening rounds in a five-to-ten year process of cross-border, retail banking and consumer finance consolidation.

The evidence to date

Certainly, there has been a flurry of large cross-border retail financial services deals in 2004 and the first half of 2005. In November 2004, Spain’s Grupo Santander was the first financial services group on the pan-European acquisition trail, buying the UK’s Abbey. Santander is now a top ten global bank and earns the majority of its revenues from retail financial services. In 2005, this has been followed by a furious string of proposed cross-border deals. In Europe’s largest cross-border merger to date, Italy’s Unicredito Italiano has bid for Germany’s HVB, while there have been two bids for medium-sized Italian banks. ABN AMRO of the Netherlands and BBVA of Spain, respectively, bid for Antonveneta and Banca Nazionale del Lavoro. Although BBVA’s bid has since been trumped by a bid from an Italian institution, the ABN AMRO bid for Antonveneta looks to be finalised in the final months of the year. Interest in Central and Eastern European banks has picked up, as evidenced in Romania.

There is a strong logic for believing that consolidation across the European continent will continue at roughly the same pace as consolidation followed in North America. It is natural that CEOs should turn to cross-border mergers when the relatively easy pickings from domestic mergers have been largely exhausted, and, as in some highly-concentrated domestic markets, when further consolidation is forbidden due to a prohibition on the excessive concentration of deposits and assets in the hands of a single competitor. However, this shift in emphasis from in-country to cross- border mergers involves a change in mind set and a sharp escalation in execution risk. Synergies are harder to achieve, and there are much greater risks arising from language, culture, customs, market structures, tax issues and the different regulatory environment in the target bank’s domestic market, not to mention political risk. Yet the unrelenting search for growth is leading CEOs to re-evaluate opportunities and risks, and the deals now underway are strong evidence that cross-border retail banking mergers are, after a long wait, finally a reality.

Private equity

• Accelerating the reshaping of financial services

Historically, almost all of the acquirers of regulated financial services business lines and assets have been other financial services firms – typically large banks or insurance companies already operating within the existing regulatory oversight framework. Exceptions to this rule have been joint ventures set up with retailers or outsourcing suppliers. The emergence of private equity investors on the financial services merger and acquisition field is a relatively recent phenomenon, but given the ever increasing amounts of capital that private equity firms are raising, this is a trend that looks likely to accelerate. Indeed, across 2004 and the first half of 2005, both the number of deals and the total value of financial services deals backed by private equity investors is up, a consequence of the growing pool of investable assets controlled by private equity firms.

Impact on European banking M&A

• Identifying underperforming businesses, undervalued assets

The need for high returns is driving private equity managers to scour the landscape for underperforming business lines or undervalued assets in which to invest. In contrast to traditional intra-industry M&A activity in which entire institutions are typically bought and sold, private equity firms are aggressively seeking out illiquid assets that can be monetised – like German apartment house portfolios – or lines of business that can deliver high stand-alone returns if simply invested in to create economies of scale – like closed UK life assurance books. In addition, ‘lightly’ regulated businesses such as foreign exchange bureaux have also been bought by private equity investors.

• Accelerating the line of business rationalisation process

The spotlight of value creation that private equity firms are increasingly shining on individual business lines is forcing financial institutions to re-examine the value they derive from different assets or activities. This process of re-evaluation is accelerating the pace of change for financial services firms by highlighting potential inefficiencies or points of competitive disadvantage on a business line-by-business line basis.

In particular, partly due to the change in accounting standards in regards to bad debt, a small boom has arisen in the sale of non-performing loans across Europe, with particular interest being shown in Italy and Germany, as banks find it more efficient to dispose of underperforming loans and redeploy their capital. Accounting rules on leasing are also changing, which is resulting in the first private equity transactions in the leasing business.

High expectations of future growth

There is undoubtedly increasing pressure on financial services companies to find earnings-enhancing mergers. Many domestic European markets offer little opportunity for organic earnings growth, yet the high level of share prices relative to current earnings assumes buoyant growth. For many CEOs, the only way to meet the expectations implied by share price valuations is through value-enhancing mergers that offer efficiency synergies and, perhaps, entry to markets with higher growth rates than their domestic market can offer.

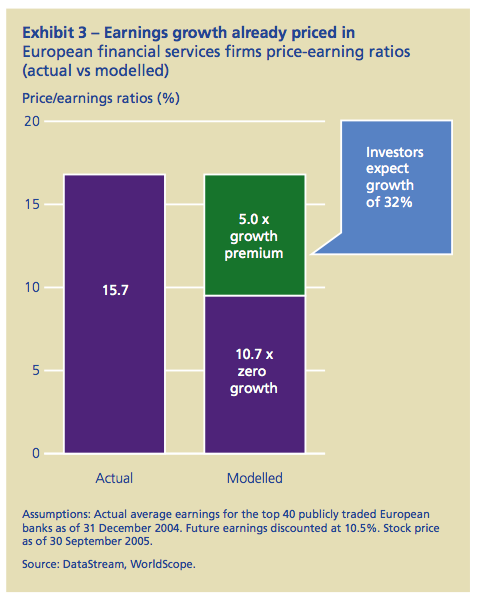

Taking the average price/earnings ratio for Europe’s 40 largest financial services companies at the end of September 2005, which was approximately 16 times actual 2004 earnings, we estimate that share prices currently embed a substantial expectation of future growth. Were banks merely to maintain earnings at their current level, we estimate that shareholders would pay a price of 10.7 times for that earnings stream. In actual fact, shareholders are paying a premium of approximately 5 times what banks have demonstrated they can earn today. In other words, shareholders, as measured by the prices they are willing to pay, are expecting the banking industry’s future earnings to grow by nearly 32% (Exhibit 3).

“From the buyer’s persepective, Gómez-Roldán, the new Abbey CEO said, there must be a clear retail business model to export, transferable IT systems and spare management capacity.”

Unicredito’s acquisition of HVB demonstrates the logic of a growth-enhancing merger. Unicredito plans to extract earnings growth from its acquisition in two ways. On the one hand, Unicredito will increase its presence in the high growth economies of central and eastern Europe. At the same time, it plans to achieve cost savings from increasing operating and support function efficiencies, as well as reduction in headcount in these economies.

While institutional shareholders have recently demonstrated their willingness to oppose high-profile deals which in investors’ opinions appear to have insufficient strategic logic (eg, Deutsche Borse’s attempt to buy the London Stock Exchange), shareholders do appear to be generally in favour of merger proposals with a sound economic rationale. For instance, there has been little opposition to Unicredito’s proposed acquisition of HVB. Indeed, with interest rates low, and equity markets generally fully valued, shareholders are keen for companies with good investment opportunities to seize them.

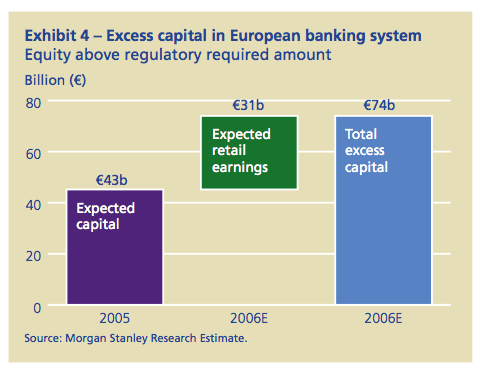

Growing acquisition war chests

At the same time, however, financial services companies have substantial excess capital that needs to be either invested productively or returned to shareholders (even before the impact of Basel II). According to calculations by Morgan Stanley, banks will have accumulated some €74 billion in excess capital by the end of 2006 (Exhibit 4). What is more, this capital will continue to amass at a rapid rate going forward. With large amounts of idle funds sitting on bank balance sheets, we would expect that many CEOs will be tempted to deploy those funds on a high-profile shopping spree, rather than simply returning that capital to shareholders.

“With large amounts of idle funds sitting on bank balance sheets…”

Falling political barriers

The European Commission is currently investigating why there have been so few cross-border financial services mergers, and has repeatedly stated that national regulators should not stand in the way of the market. Historically, certain national central banks and politicians have sought to deter acquisitions by foreign institutions, both to protect domestic jobs and, often, to try to preserve the close relationships between local banks and companies. Indeed, this issue has moved to centre stage due to the allegations of bias made against Antonio Fazio, the Governor of the Bank of Italy, in his oversight of the ABN AMRO bid for Antonveneta. At the time of writing, Governor Fazio is facing increasing calls to resign because of his alleged favouritism toward an Italian suitor in the bidding for Antonveneta, raising the issue of domestic interference in cross- border mergers within a single European market to the highest levels of political scrutiny.

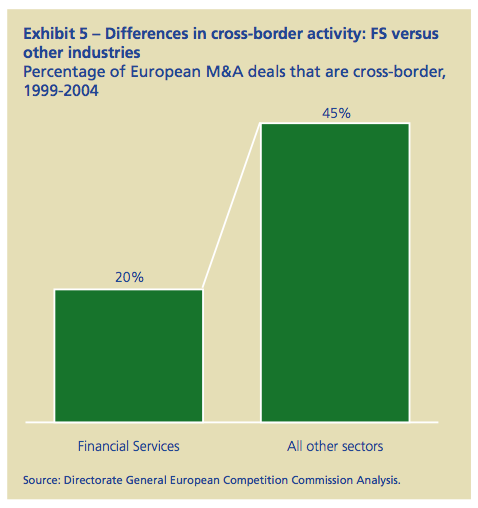

An EU analysis of all merger activity in Europe over the past five years is revealing in terms of identifying the scope of the problem. According to the European Commission, only 20% of all European financial services mergers and acquisitions in the EU were cross-border deals, with the other 80% of deals being domestic acquisitions. This is very much at odds with all of the other industry sectors across the same period. Indeed, some 45% of all mergers and acquisitions in other sectors between 1999 and 2004 were cross-border, an activity rate that is over twice that found in financial services (Exhibit 5).

Many observers have attributed much of this cross-border activity deficit to national supervisory agencies blocking any approaches from foreign acquirers. Yet, evidence in the market suggests that central bank opposition, which has been seen as an insurmountable obstacle to any cross-border deal, is no longer the deal-breaker it once was. The UK authorities have not objected to foreign banks buying UK banks. In Germany, there has apparently been no objection from the central bank to the HVB merger. In Italy, there is a more complicated, but equally promising story.

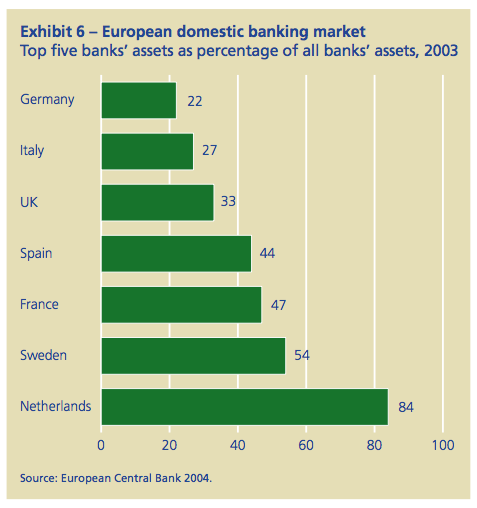

Two foreign bids for Italian banks – ABN AMRO bidding for Banca Antoveneta and BBVA bidding for Banca Nazionale del Lavoro met initial opposition from the Bank of Italy. However, the Bank of Italy quickly changed to an accommodating stance once Italian bidders for both Italian banks entered the picture. Although BBVA has ultimately lost its contest for BNL, BNL’s acquisition by an Italian has contributed to overall banking consolidation in Italy, the second most fragmented domestic banking market in Europe (Exhibit 6). At the time of writing, the ABN AMRO bid for Antoveneta appears to be successful, after charges of bid rigging in favour of the Italian suitor for Antoveneta have emerged.

Finally, the tax treatment of European cross-border businesses appears, slowly, to be turning increasingly favourably. A number of European Court opinions and judgements, such as the Marks & Spencer case, have ruled against the ‘discriminatory’ treatment by the home country’s tax authorities of cross-border tax issues. We expect this trend to continue.

The reason the European Commission views the removal of obstacles to cross-border consolidation in financial services as so important is the positive effect that an efficient and competitive financial services industry is believed to have on the whole of the European economy. Speaking to a banking audience at the end of May 2005, Charlie McCreevy, European Commissioner for Internal Markets and Services, said: “There is empirical evidence to support the view that integration and consolidation in banking can enhance overall economic performance via macro economic stabilisation, risk diversification, economies of scale, lower costs of capital and enhanced consumer welfare.” In fact, using the US experience as our guide, we would estimate the European banking industry as a whole can save over €18 billion of non-interest expense through the efficiency enhancements that come from consolidation. This windfall is money that flows directly back to customers, shareholders, employees and taxing authorities.

Increasing synergies and benefits

We would argue that growing cost synergies and potential revenue benefits are making mergers and acquisitions increasingly attractive. In particular, some acquisitive financial services organisations have highly efficient operating platforms and have become increasingly effective at squeezing efficiencies from their acquisitions. The Santander acquisition of Abbey was partly justified by plans to roll out its Parthenon information technology system in the UK. At the same time, the new Basel II capital adequacy regulations reward institutions with broader geographic and asset diversity by requiring them to hold less capital.

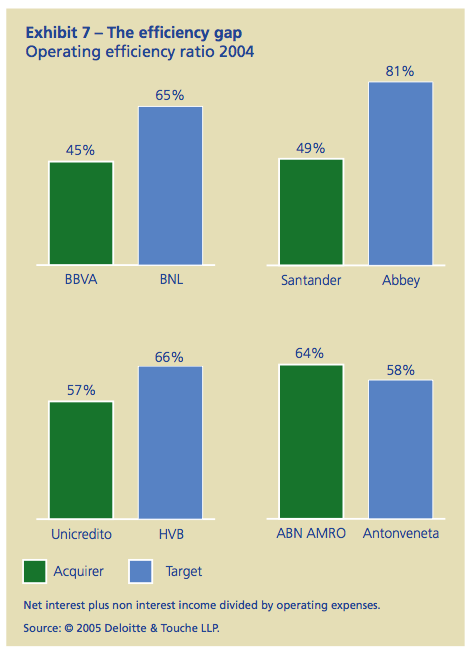

There are great disparities between the efficiency ratios of the most and least efficient banks, even allowing for the dangers of different measurement bases (Exhibit 7). Taking a look at two of the big cross-border deals – Grupo Santander’s acquisition of Abbey and BBVA’s proposed acquisition of Banca Nazionale del Lavoro – there are clearly gains to be made in each case from cost efficiencies. The acquirers have vastly more efficient operating platforms, in the form of IT systems, processing platforms and product sets that they intend to replicate in their newly acquired institutions. According to Deloitte analysis, Santander’s efficiency ratio of 47% was superior to Abbey’s performance, even after taking into consideration Abbey’s much publicised revenue shortfalls in certain businesses which contributed to its outsized 81% cost/income ratio. Similarly, BBVA’s 45% is considerably better than Banca Nazionale del Lavoro’s 65%. Of the recent proposed cross-border acquisitions, only ABN Amro has been less efficient than its target, but in that case there is a different, but equally compelling economic rationale for the merger, as we explain further.

With IT forming an increasingly large percentage of fixed costs, having the right infrastructure and managing it correctly is vital. Merging IT infrastructures is a key integration skill as previously demonstrated in deals within countries and in the larger US transactions. Some of the more acquisitive financial services organisations have done enough deals that they now have developed a track record for migrating their acquisitions onto their own IT platforms.

A related area where efficiency improvements can be made is back office operations. Some organisations are seeking to adopt a global model, with back office administration conducted in low cost locations. This may, however, be difficult to bring about in parts of Europe where there is acute sensitivity about job losses. We would argue that an acquiring organisation can still generally make efficiency gains through introducing a better business model.

From the perspective of capital, the Basel II capital adequacy regime, which comes into force between year-end 2006 and year-end 2007, will introduce more risk-sensitive minimum regulatory capital requirements. One implication of this regime is that the amount of capital required to support a given level of business activity will be reduced if those businesses are diversified. So a pan-European bank with, for example, credit card books in two countries would need a smaller amount of capital to support this than a bank with a similar sized credit card exposure in just one of these countries. The logic is that the repayment risks, and economic cycles behind them, differ in each country offering some portfolio diversification.

It should also be mentioned that the introduction of IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards) will make accounts increasingly transparent, making it easier to conduct thorough due diligence and to compare financial information between institutions in different countries, highlighting the gap between strong and poor performers.

“There are great disparities between the efficiency ratios of the most and least efficient banks, even allowing for the dangers of different measurement bases.”

Disaffected customers: price trumps nationalism

The ultimate consumers of European retail financial services, citizens across Europe, are certainly eager to embrace more competitive banking, assurance and saving products. In a recent YouGov survey of 2,300 retail banking customers across Europe, the polling organisation asked people if they would buy products from pan-European providers. Some 68% of respondents said they would.

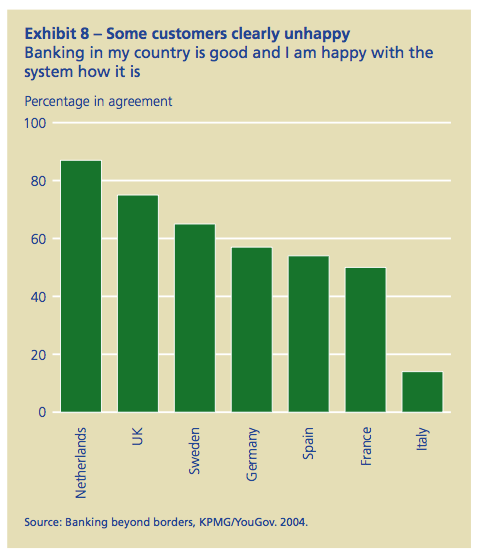

In order to gain greater insight into the opinions of Europe’s banking customers, YouGov sought to establish whether the people of different countries were happy with their banking systems. Interestingly, there is a stark contrast in attitudes. According to this survey, while in the Netherlands and the UK, for example, people are by and large content with their banks, in Spain and Italy there is dissatisfaction. In Italy, in particular, the overwhelming majority of citizens are deeply unhappy with the banking system (Exhibit 8).

“According to this survey, while in the Netherlands and the UK, for example, people are by and large content with their banks, in Spain and Italy there is dissatisfaction.”

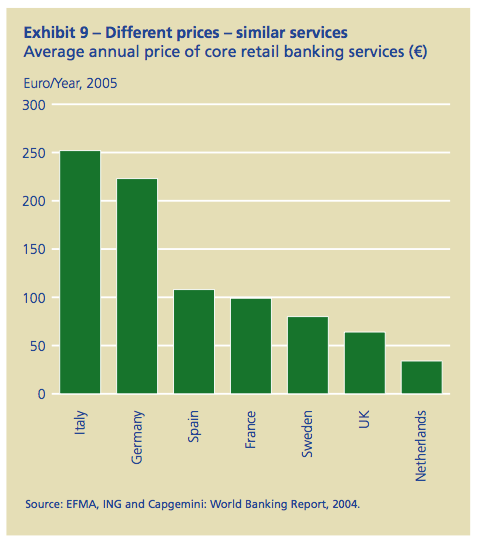

This is not difficult to understand when one looks at the wide difference in prices paid by financial services customers in different countries. The Italian customer pays an average of €250 a year for banking services, while a British or Dutch citizen pays from €30 to €60 a year for the same basket of products and services (Exhibit 9). Clearly, a strong motivator behind ABN AMRO’s ongoing struggle to acquire Antonveneta is the opportunity to introduce a set of products and services with a radically different pricing structure into the Italian market, using its existing IT platform, business model and underlying retail banking expertise.

What this means is that product nationalism, while still present, seems to be giving way. For many Europeans the more pressing issues are value for money issues. Indeed, there is a great deal of pent-up demand for lower prices and more competition in some markets. This increases the opportunities for efficient pan-European retail banks to enter historically more expensive markets and begin offering more competitively priced retail banking services.

Life assurance in the spotlight

Overview

The broad cross-border consolidation trends that we see emerging in retail banking – pressure for growth, excess capital, relaxed political restrictions, receptive consumers – will affect the life insurance sector differently for two fundamental reasons:

Different profit pressures

First, the insurance industry is beset by numerous pressures on profitability, unlike the strong returns being generated by the retail banking industry. Insurance firms are simultaneously dealing with the need for additional capital, low-equity returns, increased regulatory scrutiny and at least until fairly recently, unhealthy stock prices.

Different starting point

Second, the insurance industry is already more international than retail banking. A wave of European cross-border mergers and acquisitions has already washed across the insurance industry in the 1990s, creating a stable of pan-European competitors – Aviva, AXA, Allianz, Zurich, Generali – with strong operations in most European countries. Prudential has strong businesses in Asia, and the US, along with some bancassurance.

Crystal ball: predictions for the insurance industry

With regard to merger and acquisitions, we believe that the insurance industry will, in the near term be much quieter than retail banking. While there will be deals done or proposed – such as the proposed Old Mutual/Skandia deal – high-profile, headline grabbing deals will be fewer and farther between. That said, we do expect the following to occur:

Portfolio pruning

Much of the acquisition activity in the insurance business was completed with little regard to the lines of business, distribution channels or geographies of acquired competitors. Many insurers are looking to unload non-critical assets to boost capital, increase the amount of management attention that can be paid to other parts of the organisation and allow them to focus on their core business. This trend has been gathering force across the past year and looks to continue, especially due to the additional pressure for realising value from individual business units coming from private equity investors.

Closed book consolidation in the UK

Two high profile acquisitions, Resolution Life’s takeover of RSA’s life insurance business, as well as HHG’s sale of its Life Services business by Life Company Investor Group are key deals in what we see as a gathering trend of closed life insurance book consolidation in the UK. The economies of scale available in large book administration are driving the creation of specialist firms able to service ever more policies off a relatively fixed cost base. The compelling economics of these deals will drive more of them in the coming years, provided regulators believe policyholders interests are being protected.

Few strategic cross-border deals

A lack of compelling economics and the urgency of cost inefficiencies and capital replenishment will mean that cross-border deals will be the exception, not the rule. The early rounds of courtship between Old Mutual and Skandia are reflective of the caution surrounding geographic expansion in insurance in comparison to the more vigorous competitive environment displayed in cross-border retail banking.

Lessons learned from cross-border insurance M&A

Although Europe’s continental insurance competitors were created a few years ago, many of these companies still operate in a fairly decentralised manner. There was much less emphasis in most of the cross-border mergers on maximising the operational efficiencies of the newly created group and this country-first approach has resulted in significant differences in operational efficiency country-by-country. This focus on individual domestic autonomy at the expense of cross-group efficiency has left many insurers with a challenging agenda of operational cost issues to deal with.

The lesson for retail banking executives from the experience of these first movers in creating transnational financial services firms is to identify and emphasise operational efficiency opportunities early in the merger process. Indeed, executives must highlight the synergies and gains that underlay every bid even before the deal is consummated if they hope to gain the backing of shareholders.

Where does this leave banc assurance and general insurance?

For banc assurance (banking and insurance combined) there is less opportunity for creating pan-European economies of scale due to the differences in national tax regimes and savings preferences. Similarly, there are only limited benefits to be had from pan-European mergers in general insurance. We do expect to see corporate activity in these sectors, but this will be driven primarily by capital weakness and lack of profitability. We believe that the next five years will see a reduction in the number of life assurance and general insurance companies, although the largest will retain an international presence in order to service their large multinational corporate customers.

The UK presents an example of the challenges facing Europe’s life assurance companies. On the one hand, the sector may have too many participants. At the same time, a virtual perfect storm of low interest rates, poor stock market returns and increased regulation has stretched capital resources while reducing profitability. In terms of regulation, Financial Services Authority rules mean that life assurers need additional capital. Meanwhile, the Government’s introduction of low cost savings products is putting downwards pressure on fees. The recently published Lord Turner report into UK pensions suggests that commission rates have further to fall.

There is now a strong trend of consolidation in the UK as specialist companies buy and run closed life funds. These specialists gain from in-country economies of scale, and benefit from being able to buy life funds at substantial discounts to their long-term embedded values.

In continental Europe, the pressures are not yet so great, although the introduction of Solvency II by the European Commission in 2010 will have a similar impact on the capital structure of both life assurance and general insurance providers across Europe. Even so, there will be rationalisation as some companies seek to divest foreign subsidiaries, and smaller companies merge. A number of life companies made cross-border acquisitions several years ago, only to find that they had overestimated the demand for banc assurance products and underestimated the difficulties in terms of divergent tax regimes and retail savings cultures.

Although the logic for cross-border retail insurance acquisitions is less compelling than that in retail banking, we would expect a few targeted deals as large life companies exhaust the growth opportunities in their home markets or adventurous banc assurance institutions make another run at building a regional one-stop retail financial services institution. Eventually, even insurance will experience more consistent accounting principles via IFRS.

Conclusion

So where does all this lead?

We contend that by 2010, cross-border retail banking mergers will have created pan-European financial services behemoths similar to the national retail giants in the United States. Market concentration across the continent will increase significantly, with the biggest financial services companies controlling a larger share of the total retail market for banking and saving products. This process may start with more in-fill deals but as the successful banks see their market capitalisation increase, we are likely to see the long awaited transformational deals as the Global and European top ten premier league settles down. Our experience is that cross border transactions which are true ‘mergers of equals’ are difficult and bank CEOs shy away from them; but where there is a dominant partner the benefits can outweigh the costs and CEOs become more interested.

For the acquiring financial services institutions, this should lead to potentially higher earnings growth on the whole, although it would be foolishly optimistic to suggest that all mergers will create shareholder value given the execution risk and economic cycles. Meanwhile, the shareholders in the acquired organisations should benefit, as these will typically only divest their holdings if their shares are bought at a price premium.

Across Europe as a whole, financial services will become a more efficient industry, with gains for the economy as a whole. Billions of euros that are currently spent in financial services will be saved through more efficient operating procedures. What is more, increasing competition should drive down pricing, allowing Europe’s consumers the opportunity to gain from better value current accounts, savings accounts, mortgages, life assurance and other products. Additional competitive pressure will continue to be brought to bear by cross-border internet providers like ING Direct.

Bets are also being placed elsewhere. After buying Crédit Commercial de France, HSBC has been focusing on Asia and has also bought into the United States via its acquisition of Household International. RBS continues to expand in the United States while, Barclays, in addition to its purchase of Banco Zaragozano in Spain has boldly re-entered the South African market through its purchase of Absa.

While there will still be room for national institutions, particularly in sectors where there are specific national product sets such as banc assurance, we anticipate that a handful of pan-European retail banks will emerge, serving citizens from the Mediterranean to the Baltic and the Urals to the Atlantic. It is the winners in this race that will have a reasonable expectation of sitting at the top of the retail banking league tables and reaching the coveted top five global ranking. The arena of competition will expand, with these European retail banking champions possessing the scale, sophistication and earnings power to match and compete with any of the world’s largest banks.

Appendix

Consolidation analysis analytical note

The consolidation analysis graph shown below attempts to condense onto a single chart the analysis undertaken to compare the US banking industries consolidation experience with that of the EU.

We believe that many of the factors evident across Europe were, to a greater or lesser degree, in evidence in the US. Both retail banking markets were, in aggregate, extremely fragmented. Banks in both markets were barred from acquiring banks across political boundaries – banks in the US were not allowed to acquire banks across US state lines until the late 1980s and banks in the EU were, for all intents and purposes, barred from acquiring across domestic borders until the

mid 1990s. Political forces were at work in both markets to free up the industry to begin real consolidation by removing the legal barriers to cross-border or cross-industry acquisition with the repeal of the Glass- Steagal act separating banking from investment banking in 1995, and the adoption of the EU Financial Services Action Plan in 1999.

To identify the pace of change and draw comparisons we looked at the total number of banks in the US from 1985 to 2004 and observed that there was a loss of banks in each year – some mergers being in a single state, some being across state lines – but all serving to contribute to a less fragmented, more concentrated banking market across the totality of the US. Similarly, in the EU, we looked at the total number of banks across the EU 15 countries from 1997 to 2004 (the only years for which data is available).

In each market, we found the year in which the most banks disappeared – 1995 in the US and 1999 in the EU. From that point forward, each market continued to see shrinkage in the number of banks, but, by definition, at a slower pace from the peak.

Our analytical graph overlays the experience of the EU onto the US from both their high points of consolidation. To try to make the comparison simpler, we indexed the rate of change numbers to 100 for each market. So 1995 in the US, when 5.01% of the banks were taken over, equals 100. In 1996, year one post the high-water mark of consolidation, only 4.31% of the banks were acquired, a rate of acquisition that is only 86% of that experienced in 1995.

Similarly in the EU, we identified 1999 as the year when the most banks were acquired and indexed the rate of consolidation – 4.98% – to 100. In 2000, year one after the high-water mark in the EU, 4.95% of the banks disappeared, so the rate of acquisition is 99% of that experienced at the market’s peak.

This analysis carries on, year over year, and we see that five years on from the height of market consolidation, the US shrank at a rate of 62% of that which it experienced at the peak. The EU, by contrast, shrank at a rate of 57% of that which it experienced at the peak of banking industry consolidation.

Additionally, in the US from 1995-2000, an average of 3.45% of the banks were acquired each year. This is remarkably similar to the rate at which EU institutions were acquired across the period 1999-2004 – an average of 3.69% of the banks disappeared each year.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter