Publications M&As — The Long And The Short Of It

- Publications

M&As — The Long And The Short Of It

- Michael Tierney

SHARE:

When mergers and acquisitions grab the headlines, it’s often the big deals that move the markets and capture the attention of investors, analysts and the general public. Certainly there have been plenty of blockbuster transactions in recent months as companies loaded with cash have made M&A activity a central part of their quest to build shareholder value.

But are the big players generally the most successful in delivering on share price once those strategic deals are announced? According to new research carried out by Cass Business School in London for Towers Perrin, medium-sized acquisitions produce better medium-term returns for shareholders than multibilliondollar transactions.

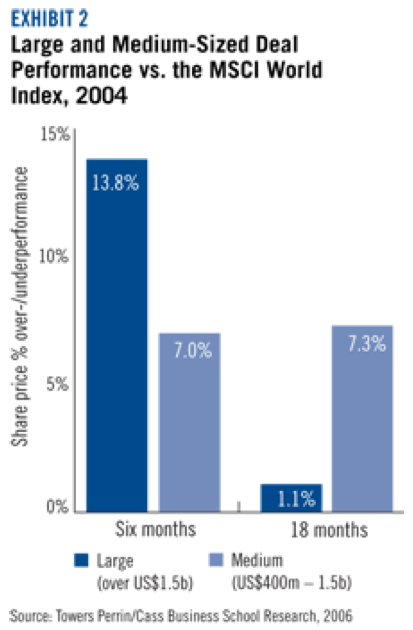

The study, conducted in two phases, examined financial performance six and 18 months following M&A deals and found a clear difference between mid-range transactions ($400 million to $1.5 billion) and those greater than $1.5 billion. Large deals are successful six months after the deal’s completion, over-performing the market by 13.8%. But, after 18 months this edge dwindles to just 1.1%. By contrast, medium-sized deals over the same period of time outperform the market by around 7% — showing longer-term success.

Phase II of the research confirms the findings of the first phase, which showed that in the current merger wave we are seeing a reversal of the historical trend — most deals now do generate value. However, Phase II findings suggest that the larger the deal — and the bigger the promise — the less likely it is to bring gains to investors over the medium to long term.

M&As HAVE ENTERED A SUCCESSFUL ERA

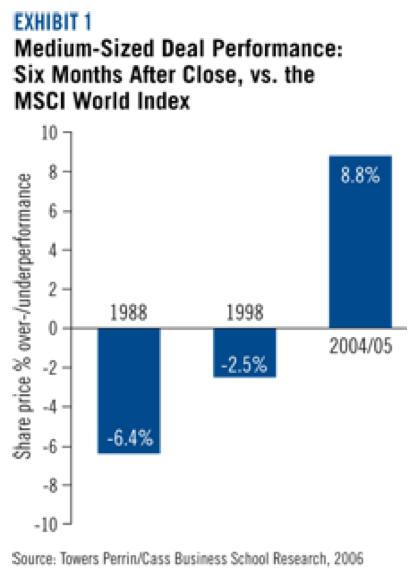

M&A deals in both 2005 and 2004 outperformed the market, building shareholder return. In contrast, transactions in 1998, and even more so in 1988, eroded returns to shareholders. By all evidence, M&As have entered a successful era (see Exhibit 1).

SIZE MATTERS

A stark contrast is seen, however, in the timing of returns between mediumsized deals and large deals. Big no longer appears to be beautiful, at least not for the longer term. In the six months immediately following a large deal, shares outperform the market by 13.8%, a strong boost in shareholder value. But the figure tumbles to just 1.1% after 18 months (See Exhibit 2). Medium-sized deals, on the other hand, do better, outperforming the market by around 7% after 18 months. Nonetheless, companies continue to pay a sizable premium for larger acquisitions.

According to Dealogic, a market analysis company, the average premium paid for deals over $1 billion was 16.5%. While that is considerably lower than the average premium of 27.4% for transactions worth $100 million up to $1 billion, it still confirms a large gap between price and outcome in the case of larger deals. We believe there are two key reasons for this:

Large household-name transactions, with massive sticker prices, invariably attract a lot of media coverage, which can create shareholder euphoria that is not always fully justified by fundamentals. Share price rises to unrealistic levels that can’t be sustained over the long term.

Big can mean hard to integrate. Capturing desired synergies when two large organizations of similar size come together is much harder than when a smaller target is simply absorbed by an overwhelming acquirer.

THE DIFFICULTY LIES WITH EXECUTION

One of the key factors influencing deal success or failure in the eyes of the market is the price paid for an acquisition or merger. Looking at the decline in the size of shareholder returns over time following the initial euphoria begs the question: Are companies simply paying too much for targets in larger deals? Actually, no, when you remember that the premium paid for deals over $1 billion is considerably lower than that for transactions worth $100 million up to $1 billion.

The drop in shareholder return has to do with a failure to make the deal work in line with expectations. The difficulty lies with execution — and much of the execution takes place during the integration period of a merger, when people and culture issues rise to the surface.

In our consulting experience, we find that failure to adequately prepare for and address people and culture issues is a key reason deals don’t deliver anticipated value. Towers Perrin’s Global Workforce Study (a study of 86,000 employees in 16 countries) revealed that M&A transactions can weaken employee engagement (the amount of discretionary effort employees are willing to put into their jobs). Specifically, the Global Workforce Study found that in the U.S., employees who have recently experienced a merger or acquisition in their organization are somewhat less likely to be highly engaged (19% versus 21% of our overall U.S. sample) and somewhat more likely to be disengaged (18% versus 16% of the total group). For U.K. companies, the study found that deals were less disruptive to highly engaged employees, but there was a noticeable increase in the number of those who became disengaged.

For large employers with thousands of employees, this suggests that an M&A can have a negative impact on a significant number of people, including many high performers. Just when the company needs to draw on employee cooperation to ensure the success of the M&A, the employee engagement levels are dissipating — which can negatively impact business results. Mission-critical people leave. Duplication of processes and activities creates confusion and slows things down. Promised efficiencies and innovations don’t materialize.

GREATER EMPHASIS ON POST-DEAL IMPLEMENTATION

Few large firms believe anymore that integration happens by straightforward, top-down instruction to the lower echelons of the enlarged organization. We attribute the much stronger performance of M&As in 2005 and 2004 in part to the greater emphasis that companies place on post-deal implementation. Still, there is an understandable tendency to concentrate on the financial synergies and to view the people issues, including important employee considerations, through that lens.

This line-item focus on the numbers may explain the short-term boost to shareholder return — arguably, the larger the consolidation, the better the opportunity to excise big costs. In the longer term, however, companies need to integrate brands, intellectual assets, systems and processes, all of which demand retention and engagement of employees at all levels. These are challenging tasks under the best of circumstances and can easily be undermined by the distractions and uncertainties that come with any merger.

Part of the reason medium-sized M&As achieve more success in the longer term, despite paying what seem to be much higher acquisition premiums, may stem from the smaller-scale integration challenge: The task is smaller because it involves fewer people, processes and operations. Also, there may be fewer overseas outposts to digest — reducing the potential conflicts associated with differences of national cultures. Early indications are that local deals work better than international.

BETTER DEALS, BETTER GOVERNANCE, BETTER SUCCESS

We believe that the less successful waves of M&A activity in 1988 and 1998 were characterized by less-than-rigorous governance throughout the entire process of identifying and acquiring target companies. We saw a broad array of nonfinancial motives behind transactions, which overshadowed in many cases a detached evaluation of the acquisition price. As a result, companies often paid large premiums in a bidding war or as a defensive tactic.

Today, shareholder, media and rating agency scrutiny of management decisions is far tighter than before. Much more care is taken with due diligence. Once an implementation afterthought, corporate benefit programs — pension plans in particular — are now examined minutely to assess financial liabilities. Several large proposed M&As have been called off in recent years after due diligence exposed some unappetizing pension liabilities. With more interested parties looking over their shoulders, people in management now have to focus more assiduously on creating shareholder value — the pervasive trend toward openness and transparent corporate governance has influenced all aspects of business behavior.

As senior manager goals become better aligned with shareholders’ interests, we can expect to see managers becoming increasingly picky about which deals to do.

IMPROVING THE ODDS

In our view, M&A know-how has improved significantly. There is now much more experience among all parties involved in the deals, from CEOs, CFOs, COOs and HR directors to project teams, lawyers and consultants. In 1988 — and to a lesser but significant extent in 1998 — inexperience resulted in M&A transactions conducted by trial and error, in terms of both deal selection (and pricing) and deal execution. Too often, the errors led to poor financial results.

We believe that the improvements we have seen in deal selection, deal governance and integration focus have contributed significantly to the ability of M&A managers to achieve critical deal objectives, including higher returns for shareholders. To reach these objectives and improve their chances of success, companies — especially the larger ones — need to focus on some of the more people-related issues that are often overshadowed in the scramble to manage M&A deals.

The earlier the involvement of the human resource function — especially at the due diligence stage — the better the prospects for successful integration throughout the new organization, from leadership and top team selection to broader people and cultural issues.

To remain productive and deliver sustained shareholder value, companies need to understand the people costs going in: the cost to retain talent, the long-term effects on workforce demographics and how the merged entity will align laborcost projections. All of this must be accompanied by a plan to manage cultural differences and effectively integrate people programs and practices. Larger companies seeking to avoid the pitfalls associated with big M&A deals can improve the odds of success if they pay especially close attention to the project management tasks of integration and stay focused on building a common culture.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter