Blog Hindsight or Foresight: Reassessing the DaimlerChrysler Deal as Merger of Equals or Acquisition

- Blog

Hindsight or Foresight: Reassessing the DaimlerChrysler Deal as Merger of Equals or Acquisition

SHARE:

The 1998 announcement of the DaimlerChrysler merger was acclaimed as a milestone in the automotive industry, bringing together the German automaker Daimler-Benz and the American company Chrysler Corporation. However, the question of whether this union was a genuine merger of equals, or a takeover, remains unresolved. This article examines the key factors and events surrounding the merger, delving into the arguments from both parties to shed light on the nature of this historic partnership and whether perceptions have changed over time.

Merging Giants: Daimler-Benz and Chrysler Corporation

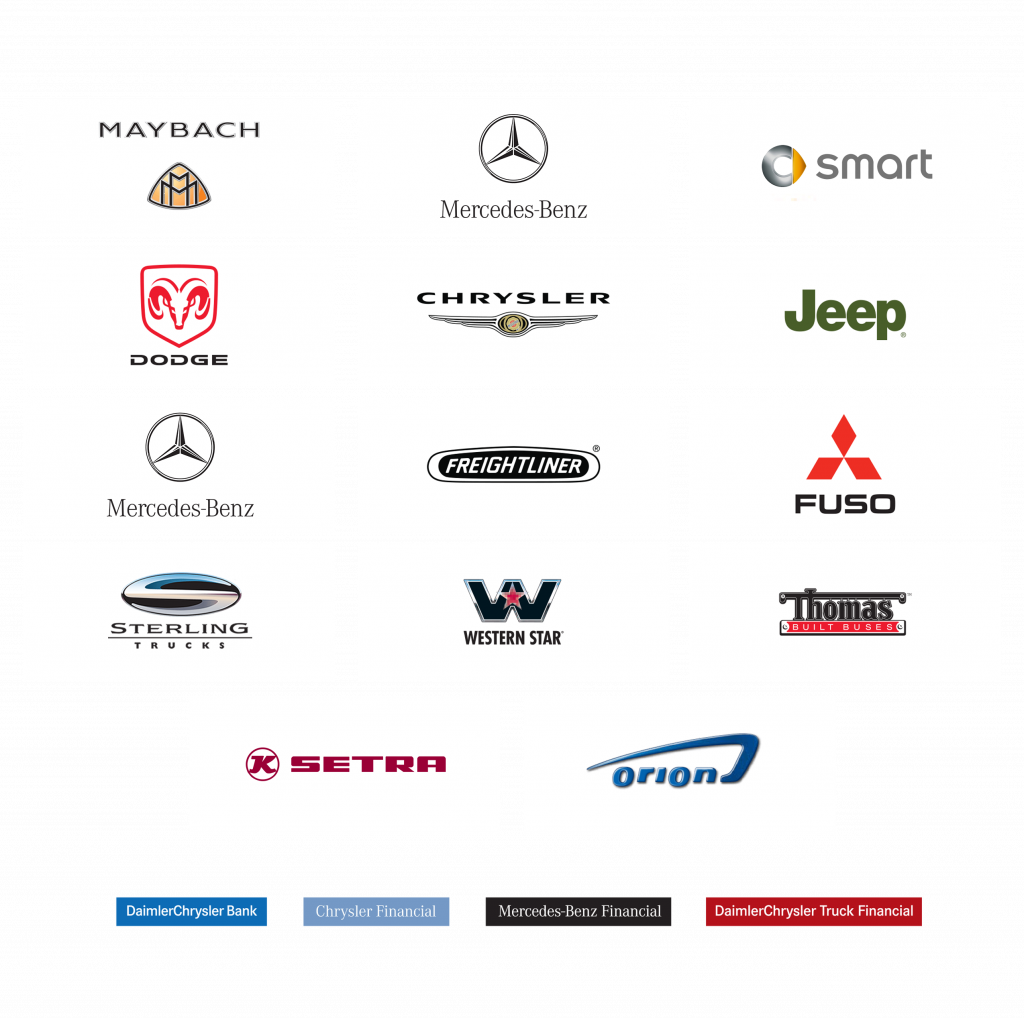

The DaimlerChrysler merger occurred at a period when the global automotive industry was undergoing substantial transformations. The primary objectives of the merger were to establish economies of scale, capitalize on complementary strengths, and strengthen the company’s position in the global market. The merger was viewed as a chance for Daimler-Benz to enter the lucrative American market, while Chrysler would gain access to Daimler-Benz’s advanced technologies and global reach.

At the time of the merger, Daimler-Benz was not “big enough” and aspired to reach Critical Mass. The company’s profitability had declined, particularly in the prestige car division. Chrysler, on the other hand, struggled with its market position. It was difficult for the American automaker to compete with its larger rivals, particularly in the prestige and international markets. Both companies viewed the merger as a strategic move to collectively address these challenges.

Both Daimler-Benz and Chrysler, according to proponents of the “merger of equals” theory, brought valuable assets to the table. They emphasize the power-sharing structure that was initially instituted, with co-chairmen Jürgen Schrempp of Daimler-Benz and Robert Eaton of Chrysler. Additionally, both companies were represented on the board of directors, nurturing a culture of shared decision-making.

Under the Microscope: Scrutinizing Claims of Equality

At the time of the merger, both companies were confronting challenges, according to some advocates of this theory. The merger was viewed as a strategic move to combine their resources, expertise, and market presence to increase their global competitiveness.

In addition, proponents assert that the merger led to the exchange of technological expertise. Chrysler contributed its strong presence on the North American market and expertise in minivans and trucks, while Daimler-Benz brought its expertise in luxury car manufacturing, sophisticated research, and development capabilities. This synergy was viewed as the propelling force behind the merger, and it demonstrated that both companies contributed equally.

Unveiling Imbalances: The Takeover Argument

Critics of the merger argue that it was essentially a Daimler-Benz takeover. They point to numerous indicators of an imbalance of power. The financial factor was a significant factor.

Those in favor of the acquisition theory also cite the substantial cultural differences between the two companies. Daimler-Benz’s corporate culture was hierarchical and engineering-focused, whereas Chrysler’s was entrepreneurial and flexible. Critics assert that the dominant German culture overshadowed the American side of the partnership, resulting in an imbalance of decision-making authority. In addition, the eventual rebranding of the merged company as DaimlerChrysler as opposed to a more neutral name was viewed by many as evidence of an acquisition. The decision to position the Daimler name first in the new company’s title contributed to the perception of an imbalance of power.

On Perceptions: Evolving Views on the Merger

Was it apparent from the start, or is this a retrospective view?

Depending on one’s perspective, the DaimlerChrysler merger was either a merger of equals or a takeover. At the time of the merger announcement, there was considerable optimism and hope for a partnership that would capitalize on both companies’ strengths. The rhetoric surrounding the merger highlighted equality and mutual advantage. Nonetheless, as time passed and the process of integration progressed, certain dynamics and events cast doubt on the initial perception of equality.

Numerous critics argue that the power imbalance and cultural differences were evident from the start but may not have been fully acknowledged or recognized. With the benefit of hindsight, it is now simpler to identify the indicators that Daimler-Benz would play a more dominant role in the merged entity. The financial discrepancies, cultural conflicts, and eventual rebranding are interpreted as indications of an underlying takeover narrative.

Reflections: 20 Lessons from the DaimlerChrysler Merger

The DaimlerChrysler merger provides valuable lessons for future mergers and acquisitions in the automotive industry. The following lessons can be derived from this historic collaboration:

- Cultural Compatibility Isn’t Optional: The cultural differences between the American Chrysler and the German Daimler-Benz were a significant factor in the merger’s difficulties. Being aware of and planning for these cultural differences is crucial.

- Merger of Equals Rarely Are: Although the deal was presented as a “merger of equals,” the reality was that Daimler-Benz was the dominant party. This disparity led to feelings of resentment and culture clashes.

- Integration Over Autonomy: Initially, the companies aimed to allow each other a degree of autonomy, but this proved problematic in achieving synergy and harmonization in the business operations.

- Clarity in Leadership: The co-leadership structure between Jürgen Schrempp and Robert Eaton was confusing and inefficient. A clear, agreed-upon leadership hierarchy needs to be established from the outset.

- Meticulous Due Diligence: Daimler-Benz’s failure to fully understand Chrysler’s financial position and its reliance on sales of less profitable, low-end vehicles was a significant oversight.

- Communicate Changes Effectively: The change in strategy from a “merger of equals” to Daimler-Benz taking control of Chrysler wasn’t communicated effectively, leading to mistrust and lack of cooperation.

- Manage Brand Perception: The prestige and perception associated with the Daimler-Benz and Chrysler brands were very different, which created challenges in marketing and brand management.

- Understand Market Differences: The U.S. and European automotive markets have significant differences, and a lack of understanding of these variations can lead to ineffective strategies.

- Strategic Alignment: Daimler’s focus on high-end, luxury cars and Chrysler’s on affordable, mainstream vehicles led to strategic conflicts.

- Manage Employee Expectations: Differences in pay scales, benefits, and working styles led to dissatisfaction and high turnover among Chrysler’s executives.

- Plan for Regulatory Challenges: The differences in safety and environmental regulations between the U.S. and Europe posed significant challenges for the combined company.

- Recognize Labor Differences: Differences in labor practices between the two countries, including the role of unions and labor costs, were underestimated.

- Consider Customer Loyalty: American consumers’ loyalty to Chrysler as an American brand was overlooked, leading to a drop in sales following the merger.

- Don’t Overestimate Synergies: The anticipated synergies, particularly in terms of shared technology and platforms, proved to be much harder to realize than expected.

- Respect Business Cycle Sensitivities: Chrysler’s higher sensitivity to economic downturns compared to Daimler-Benz was underestimated, leading to severe losses during the 2001 recession.

- Transparent Financial Reporting: Concerns about transparency and accurate financial reporting can arise when merging companies have different accounting practices.

- Involve Key Stakeholders: Involving and engaging key stakeholders, such as employees, dealers, and suppliers, in the integration process can foster collaboration and buy-in.

- Address Power Imbalances: Clear mechanisms and agreements must be in place to address power imbalances and ensure that decision-making is fair and inclusive.

- Flexibility in Integration Strategies: Adapting integration strategies and being open to new approaches can help overcome challenges and improve outcomes.

- Continuous Evaluation: Regularly evaluating and reassessing the progress of the merger is essential to identify issues and make necessary adjustments.

The debate surrounding whether the DaimlerChrysler merger as a merger of equals or a takeover remains subjective, with legitimate arguments on both sides. While proponents of a merger of equals emphasize the mutual benefits and shared decision-making structure, opponents argue that financial disparities, cultural differences, and the rebranding of the company indicate a takeover. The initial optimism about the merger may have given way to a retrospective understanding of the power dynamics at play as time passed. The true nature of the merger may be a complex mix of cooperative efforts and unequal power relations. Ultimately, the DaimlerChrysler merger functions as a case study illustrating the complexities and challenges of merging companies from different countries and cultures, as well as how the perception of such mergers can evolve over time.

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter