Publications Cross-Border Transactions: Spotlight On China

- Publications

Cross-Border Transactions: Spotlight On China

- Bea

SHARE:

By Dave Read and Bob Partridge – Ernst & Young

“A World of Opportunity”

Today’s dynamic transactions market presents a world of opportunity. As corporations and other investors turn their attention to international opportunities, they are looking beyond traditional markets to achieve high growth and competitive advantage. Ernst & Young’s ‘Cross-border Transactions’ series aims to shed light on the complex and rewarding transaction landscape in selected emerging markets.

‘Spotlight on China’, the third report in our series, provides an overview of the opportunity sectors, political context, and practical transaction considerations and challenges surrounding deal-making in this attractive Asian powerhouse.

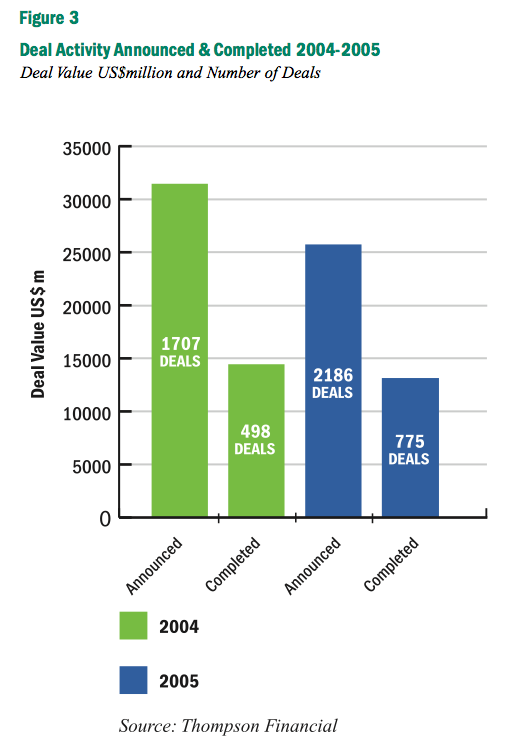

With its escalating consumer demand, outstanding economic growth and increasing foreign direct investment opportunities, the China deal market has taken off. In 2005, US$31.5 billion total deal value represented an impressive 22% increase volume over the prior year. In our recent Corporate Development Officer Study, 59% of respondents stated they were actively looking to invest in China. Interest from the international community has never been greater.

The China Question

What to do about China? Whether as market, low-cost manufacturing base or, eventually, competition for its own products, the ‘China question’ will at some stage confront every company of any size on the world stage. Given the current hype surrounding the country, the chances are it already has.

A booming economy…

China’s economic statistics make compelling reading:

• Growth. An annual growth rate averaging more than nine percent over more than two decades has not only propelled China above the UK into fourth place in the world economic league table, it is also towing Taiwan, Japan, Australia and much of the Asia-Pacific region in its wake. Chinese exports in 2004 grew by 36 percent to US$595 billion, while imports swelled by 30 percent to US$588 billionn. Growth rates of similar magnitude are expected to continue at least until 2010.

• Scale. China has a population of 1.3 billion whose per capita income has grown tenfold since 1990 and is hungry for consumer goods of all descriptions. Four percent of the population now has an income greater than US$20,000, which may not sound much but actually translates into 52 million people – equal to the population of the UK. China constitutes the largest mobile phone market in the world, and by 2020 it is estimated there will be 140 million automobiles on Chinese roads. In 2002 China overtook Japan as the world’s second-largest PC market and last year became the second largest internet user.

The property market, booming anyway in the fast-growing coastal cities, has gone into overdrive as Beijing prepares to host the 2008 Olympics. A total of US$160 billion worth of construction is adding the equivalent of three Manhattans to the Chinese capital, where work is also under way on transportation and infrastructure projects, sports venues and an airport terminal that will be bigger than all five London Heathrow terminals combined. The scale of this development, unprecedented anywhere in the world, means that China accounts for around 30 percent of global demand for many basic commodities, including oil, coal and steel.

• Resources. Chinese wages are low – and so also is average productivity. On the other hand, for those willing to seek it out, the country also possesses an increasing pool of engineering talent from Chinese universities, an improving management group as ‘returnees’ repatriate their experience from Hong Kong, Taiwan and the US, and a legendary risk-taking and hard working culture that encourages entrepreneurship and permits failure.

• Capital markets. The last two years have marked the emergence of China as a serious factor in global capital markets. In 2005 the country accounted for three of the world’s top 10 IPOs – the US$9.2 billion float of China Construction Bank (CCB) was one of the largest IPO deals ever. All told, Chinese companies raised US$19 billion in 2005, up 50 percent on 2004, and the stream of issuers shows no sign of drying up. Rather the reverse: with the Chinese government intent on pushing forward the reform of the industrial base, as well as a number of mega-deals in the offing, the Chinese authorities plan to sell off 1,300 second-ranking state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in whole or in part in coming years.

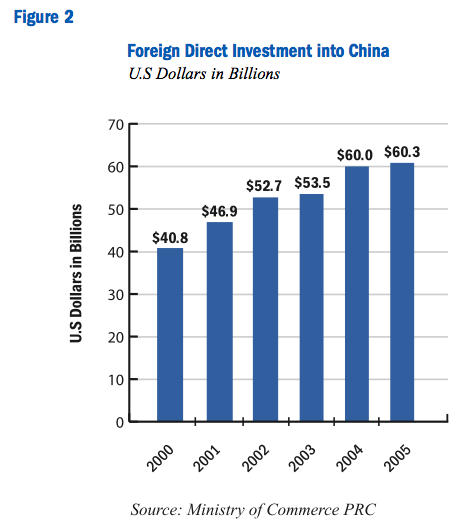

• Foreign investment. China is attracting record quantities of foreign direct investment (FDI), with totals running at around US$60 billion for the last two years. In 2004, China was the world’s preferred FDI destination: reportedly 450 of the world’s top 500 companies have a presence there. And many of their enterprises are profitable: according to the US Department of Commerce, US firms enjoyed net returns of US$6 billion in China in 2002, a sixfold increase over 2000. Seventy-one percent of US firms reported China profit rates equal to or higher than their global average. Among many others, profitable investors in China include Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola, AIG, Alcatel, Carrefour, Kodak, Motorola, Nestlé, Novell, Siemens and Volkswagen.

Given these macroeconomics, it is not surprising that many foreign companies see China not as an option but as a competitive necessity. As the figures correctly indicate, corporations are jostling to do deals in China, and many are succeeding. Yet on the ground they are finding, sometimes to their cost, that the reality undercuts the optimism:

• An emerging economy. For all its size, China is an emerging economy. Despite the evident frenzy of activity, it is frustratingly difficult to get an accurate handle on what is really going on, whether at industry level or even within a firm. The legal framework for M&A and property rights in general is hazy, and cultural differences can easily lead to misunderstandings and a mismatch of expectations.

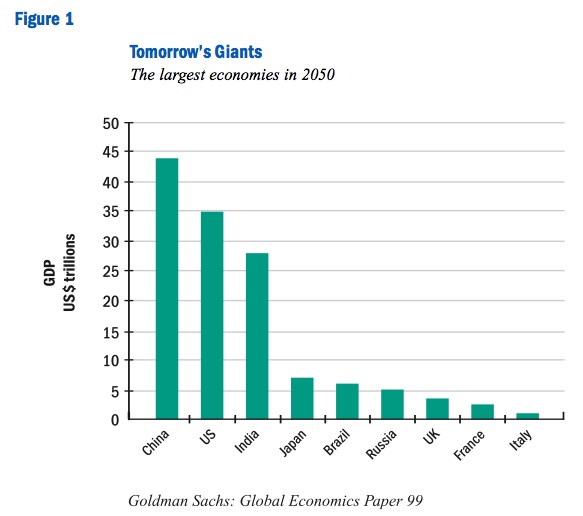

• Midsize. Fast-growing as today’s China is, as McKinsey notes a 2005 estimated GDP of US$1.8 trillion makes it no more than a midsize economic power. Even if current growth trends hold, it will not catch up with Japan until 2020 and the US before 2040. That is, for most companies’ planning horizon they will be competing for share of an economy similar to European nations such as the UK, Italy and Germany.

• Extreme contrasts. Although the scale of the Chinese market is indeed huge, the contrasts are also extreme. While average annual income reaches US$2,000 and above in the eastern coastal cities (US$5,000 in Shanghai), it is a fraction of that in the smaller cities, and some of the rural areas of the interior have been barely touched by modernization. These account for nearly half of the Chinese economy. While there is a burgeoning Chinese middle class, reaching mass consumer markets will likely require very different product market approaches from those corporations are used to at home.

• Hypercompetition. It is a serious mistake to think of China as a virgin market offering windfall returns. On the contrary: unlike Russia, where the privileging of heavy industry in the Soviet era left both consumer and small-firm sectors underdeveloped, China is characterized by intense competition and entrepreneurial activity in almost every field. This is both natural inclination and deliberate policy: while SOEs remain large in number, government ownership is declining rapidly as privatization is employed as a means of driving out inefficiencies. Apart from sensitive sectors such as energy, telecoms and defense, most of China’s industrial output is now generated by energetic private-sector companies, whether domestically owned or with foreign investment. Wafer-thin margins are the rule in most industries, and entrepreneurial domestic companies are used to subsisting on them. Even when an incomer has a technological or other advantage, weak intellectual property (IP) laws mean that it is not uncommon to find a local competitor springing up down the road making a product that is the same in all but name – but selling at two-thirds of the price.

• Overheating. The property sector is precariously poised. The central bank warned last year that China was facing a potential property bubble whose bursting could leave banks – and their foreign investors – with huge losses. Since then prices have retreated, with the danger of a further increase in non-performing loans (NPL) which are already an enormous overhang for the Chinese financial system.

• The Google factor. China does not allow some of the basic democratic freedoms taken for granted in the West. Companies hoping to do business there may have to make tough decisions about the extent to which they can accept state interference with their business principles, as in the case of Google and Yahoo!

More complicated than it looks

Turning to the supply side, all this means that the answer to a corporation’s ‘China question’ is not as evident as it might seem at first. There are two points to this: one relating to strategy, the other to deal execution. As to strategy, in the almost irresistible current buzz about investing in China, some investors are in danger of forgetting to establish clear strategic guidelines for the venture. Such a failure may create problems not only in companies’ initial approach to the market but also in the way they conduct the deal itself.

The first and most important question a company must answer about entry into China is ‘Why?’ ‘Because it’s there’ or, just as common, ‘Because everyone else is there’ is not sufficient.

Ten years ago, China strategy was about sourcing: establishing a low-cost manufacturing base to serve the rest of the world. Today the options have multiplied to include participating in China’s market growth from inside, or even exporting to it. Each of these involves a different path. If the first, it is important to bear in mind Chinese determination to move up the value chain by moving from being ‘the world’s manufacturing center’, based on labor-cost and efficiency advantages, to a ‘world-class innovation center’. If the second, companies must be aware that in many industries – automobiles, pharmaceuticals, food and drink and consumer electronics, for example – early-mover advantages have been and gone and industry positions are already well established. Volkswagen has been in China for 20 years, Motorola for 15. Correspondingly much larger investments will be needed now to disturb existing industry patterns. Whatever the rationale for entry, incoming corporations will struggle unless they can demonstrate that they are bringing something distinctive to the market that isn’t already being contributed.

Secondly, is the strategy to source a product, or, going beyond sourcing, to take an equity interest? If the latter, it is critical to be aware from the outset that while doing deals in China can be good business justifying all the hype, it is also different from anywhere else on earth. It is not only that they cannot be done overnight, and returns may take years to emerge. The bottom line is that for a variety of causes the large majority of deals never get beyond the early stages. Advisors estimate that behind headline figures suggesting that everyone is doing business in China are three ‘hidden truths’:

1. For every deal that completes and is included in the statistics, many others fall at the first or second hurdle. Just 20 to 30 percent of all Letters of Intent (LOI) finally make it through to a signed contract;

2. To get to that point may take a year or 18 months. Two years can easily elapse before a unit is operational on the ground;

3. Even after a deal is signed, agreements can still be complex to complete. It may take up to five years to tell whether a transaction will pay off. There have been several recent cases of withdrawal after several years of hard work with the realization that expectations on each side were too divergent for the deal to work.

Some of the reasons for the high failure rate for deals in China are to do with the unique environment: lack of reliable information, unclear financials and governance, legal and ownership uncertainties, and the need for regulatory approval at all stages of the transaction. Others are in the expectations that acquiring parties bring to the deal – for example a surprising number of transactions fall at a late stage when the acquirer discovers that, as often the case in China, the target is unwilling to surrender a controlling interest.

China’s unique circumstances make conducting cross-border transactions a challenge even for hardened operators. However, although it is easy to trip up, the record of successful corporations shows that the prizes for those that stay the course are considerable. The lesson of experience to date is that with the aid of trusted advisors determined and resourceful corporations can alter the odds in their favor by: a) carefully understanding the context and b) taking some simple but essential precautions that increase the chances of success and minimize transaction risk.

The rest of this report outlines how this should be done, and the prospects for transactions in some of the most important economic sectors.

Toward Transaction Success

Marco Polo reportedly took 20 years to do his first deal in China. Modern transactions are less time-consuming than that, but they are still a test of patience, nerve and the ability to maintain a balance between flexibility and knowing when to stand on principle. While the components of the transaction lifecycle – target identification, due diligence, valuation and post-merger integration – are in principle the same as anywhere else in the world, in practice in China they are very different. This is the result of both cultural factors and, overshadowing all, the dominant role that the state continues to play in the economy, directly affecting potential investors in a number of ways.

• The government still controls and allocates most of the country’s financial resources, generally privileging physical infrastructure and large industry projects. By contrast the ‘softer’ infrastructure – the institutional framework of law and IP rights, banking system and accountancy – is less well developed.

• The economy is heavily regulated. The government directly controls all economic activity through the ‘visible hand’ of tax laws and regulations, capital-market and foreign-exchange controls, and investment approvals. Regulations can change unpredictably: in 2005 new foreign-exchange rules had the effect of making it more difficult for Chinese entrepreneurs to structure start-ups for foreign IPOs, leading in turn to a fall-off in venture capital financings. After representations, the rules have since been changed again. Although investment restrictions are being gradually relaxed since the country’s admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2002, requirements and conditions are complex, often varying from industry to industry, as do the central agencies that deal with them. Percentages of a company that foreign investors are permitted to buy vary by sector; in sensitive ones only a minority foreign interest is allowed, or even none at all.

These percentages too are subject to change, although usually in the direction of liberalization.

• China’s tax system is also complicated, involving national, provincial, city and even district tax authorities, each with its own regulations. Special Economic Zones are different again. A wide variety of tax holidays may be available. How the various regimes affect a company depends on its industry, location and corporate structure. Taxes are a big issue in any China transaction.

• Despite the progressive opening of the economy to the market mechanism after 1979, there still exist an estimated 150,000 SOEs, many small or midsize, that have been used to operating in a business environment radically different from the free markets of the west.

There are two important practical consequences for would-be investors. First, it is essential to engage a team of professional advisors at the start of any transaction process. The need to understand the context and keep up with rapidly evolving regulation means that the team should include mainland Chinese talent as well as the usual specialist expertise.

Local experience is essential in conducting negotiations and building trust. Second, there is an ongoing need to maintain relations with a complex bureaucracy at a variety of different levels, including local as well as central government.

This can be frustrating and is certainly time- and energy-consuming: laws and regulations passed by Beijing are often interpreted differently at municipal or province level; sometimes they are hard to comprehend; different levels or agencies may seem to have conflicting aims. Conversely, however, good relations with government are a significant aid to doing business in China, and prudent investors will make establishing them an early priority. Many large corporations set up specialist departments to handle them.

The other essential prerequisite for dealmaking in China is to understand that most deals are asset sales and take the form of joint ventures or the purchase of a stake in a Chinese company. While Wholly Foreign Owned Enterprises (WFOEs) are increasing as sectors are opened up to foreign investment, they are still not the norm. Even in industries where WFOEs are permitted, however, they may not be easily obtainable, since Chinese owners are often unwilling to give up majority control – or if they are, it may be because the deal is overvalued. Many deals are not concluded because after a year or more of careful bridge-building targets may refuse to sell more than 49 percent. It is important that parameters such as these are set from the outset.

Target Identification

Finding and closing on good deals is difficult in China. The challenge begins with target identification. On one hand the vastness of the country, communication issues and lack of systematic industry information are all factors to be reckoned with. Increasingly investors have to look outside Shanghai and Beijing for potential targets. On the other, Chinese companies have no history of disclosure (in fact the reverse), little notion (and in many cases suspicion) of what a foreign investor is looking for and scant experience of professional advisors. In any case, numbers of the latter, although increasing rapidly, lag some distance behind demand, adding to the pressures on search resources.

In these circumstances, conventional methods such as desk research, testing the market from abroad on a frequent-flyer basis or even using teams of advisors to draw up a list of candidates on the basis of strategic industry analysis are of limited use. Sourcing deals in China is as much art as science. Prudent companies approach it as a learning experience for both sides: on the one hand a process for making targets aware of Western expectations, on the other a cross between prospecting the market and clarifying what corporate decision makers are prepared to live with in terms of control (or lack of it), regulation and bureaucratic interference in return for the perceived advantages of growth and competitive positioning.

Sourcing transactions in China is best treated as a two-part process. The initial, prospecting part is primarily a matter of networking – that is, building industry and official relationships, informal networks and establishing contacts. Again, in this process a mainland Chinese presence on the team is highly recommended. Building trust and mutual comprehension is a necessary part of the delicate initial process, and can make all the difference between making an exploratory contact and moving on to more substantive discussions.

Having established promising contacts – which may take several months – the second phase of target identification is filtering candidates that are a good enough strategic and cultural fit to be worth seriously pursuing from those that are not. Given the sensibilities and low reliability of initial information, this is a sensitive process at which many companies stumble, often because they fail to get outside help in weeding out the deals that are destined to be among the majority that never close. Investors may believe that it requires more time to court a target with a view to building trust before getting down to business. Moving directly to due diligence is sensitive (the nearest equivalent to ‘due diligence’ in Mandarin is a word meaning ‘investigation’), the target may back off and play for time.

This may prove to be a mistake. Targets may try to exploit hesitation to stall or attempt to lock investors into untested valuations or conditions. And having spent a year or more reaching this stage, the investor can get so heavily involved emotionally in the transaction that it becomes near impossible to draw a line and cut the losses. Instead, target selection (as opposed to prospecting) should be thought of as execution, using the same disciplined approach as applicable anywhere else. Of course it needs to be modified to fit with cultural expectations, and target companies will usually need assistance in understanding investor needs. But experience shows that companies that are serious about doing a deal will seldom turn down a polite but business-like request to bring in external advisors for ‘initial data gathering’ and to ‘facilitate’ a potential transaction. Those that resist are likely to be part of the majority that fail to materialize, at least without significant overvaluation.

A final point in target identification is the need to have a deal structure in mind at an early stage. This is partly to do with the regulatory environment, which may make alteration difficult at a later stage. It is also important in relation to the exit mechanism, which needs to be a consideration from the outset, in both worst-case and best-case form.

Due Diligence

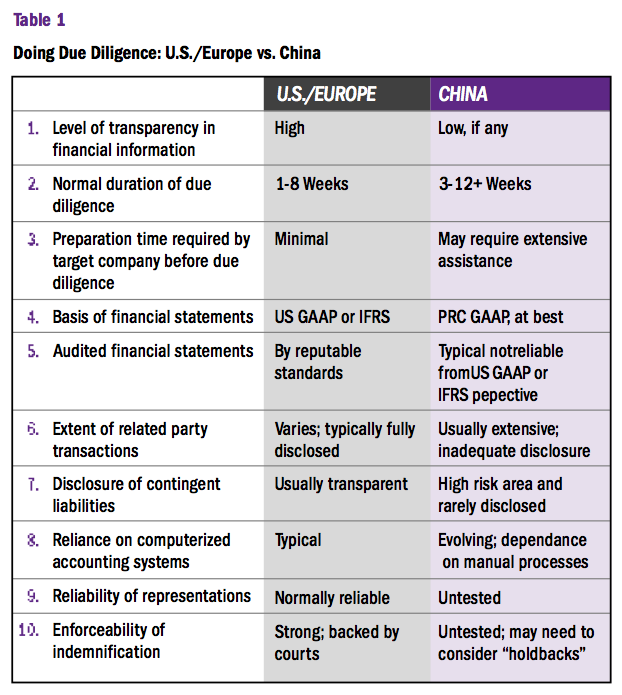

Due diligence is a critical step in any transaction, but particularly so in China. The backdrop is a country that is undergoing a dual transition from centrally planned to market economy, and from an emerging to an industrialized economy, in which the business environment is in constant change.

Due diligence is the point where this evolving business culture meets the very different norms of more developed markets, and as such it plays an important role as a process hurdle as well as the normal one of reducing risk for the investor. Many potential deals fail at this stage. Common issues for potential acquirers are:

• Accounting differences. Are the target’s financial statements audited by an international accounting firm? If not, caution is in order since accounting practices and auditing standards in China generally do not meet even China GAAP standards. Converting financial statements to the more restrictive US GAAP can often result in lower reported revenues, unexpected charges related to business combinations and reduced net profit due to stock-option accounting.

• Transparency and management processes. Accounting and management practices and procedures are often vague in Chinese companies, with information kept in heads rather than in books. There is no tradition of disclosure, which is kept to a minimum. Proper documentation and internal controls are lacking, with implications for governance as well as everyday management. All management figures should be treated as a starting point for discussion rather than undisputed fact.

• Governance. Corporate governance in China is very often weak or non-existent, even among quite large firms. Financial and accounting functions are not held in high esteem, and few of the protections for shareholders or aids to reputation-building deemed essential in foreign markets are in place. Practices such as tax avoidance and payments to induce sales are common. Since Sarbanes-Oxley, such matters are a critical due diligence area for corporate buyers. In some cases they may be a deal-breaker; at the very least investors must recognize the need to start building the foundations for sound governance practice from the earliest stage to ensure their ability to exit.

• Tax. Understanding a target’s tax situation is a critical part of due diligence. Most Chinese companies take an aggressive stance on tax reduction, often keeping different sets of books for the tax authorities and internal management (sometimes to the point where it is difficult to establish what the real position is). Tax due diligence often reveals significant hidden tax liabilities that affect the bottom line. Value Added Tax, typically the heaviest charge, is a favorite for underreporting. Hidden problems need to be carefully probed: Since there is no statute of limitation in China, a disgruntled employee can report tax violations to the authorities at any time, potentially exposing the company to prosecution. On the other hand, a variety of historic or potential tax holidays may render income tax liabilities negligible.

• Ownership and land-use rights. A common issue encountered by potential acquirers of SOEs, and most other Chinese companies, is that land is owned by the state. Issues of transferability of land-use rights often arise in due diligence and sometimes have significant financial implications as the state may require payments for land-use rights before authorizing a transaction to close.

• Social communities. Most SOEs in China operate as ‘social communities’ – that is, they have responsibility for maintaining employee housing, hospitals, schools, restaurants and even roads on their books. As these are carved out from a target entity, foreign investors may be expected to continue to provide these social services post transaction close.

This might seem a challenging list, and to the extent that the factors will affect each target in individual ways, every aspect will need to be analyzed in detail. On the other hand, the major areas where problems may hide are by now well known. The due-diligence process will undoubtedly take longer in China than it would elsewhere, but careful selection of targets and observation of the ground rules can ensure that deals proceed to a satisfactory conclusion.

The No 1 success factor, as already noted, is the early involvement of professional advisors. It is also essential to:

1. Manage internal expectations. Going into due diligence with the right expectations is critical for US and European investors. As we have seen, the quality of information and business process is lower than they are used to, resulting in the need to carefully explore risk areas. It is important to prevent deal closure from becoming an end in itself, irrespective of business rationale. Corporate Development Officers counsel strong emphasis on managing internal company expectations and avoiding overcommitment to the potential of a Chinese investment before the implications of due-diligence findings have been digested and incorporated into realistic valuation estimates.

2. Listen for the word ‘no’. One of the most fertile areas for misunderstanding is around the words ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Asian cultures are less direct than Western, and just because Western negotiators rarely hear their Chinese counterparts saying ‘no’ does not mean they are entitled to understand ‘yes’. Avoid being drawn into a false (and drawn out) process of assuming cooperation without defined actions and deadlines. When discussing potentially contentious items, it is best to put understandings in writing (English and Chinese) and agree on dates where appropriate.

3. Be prepared to go the distance – but no further. In any overseas deal market, transaction success requires patience and tenacity. Nowhere is this more true than China, where the timeline from Letter Of Intent to closing can stretch from six to 18 months or more. Not all deals will close, or are worth closing. Knowing when to hold and when to fold is likely to be the difference between failure and success.

Valuation

Valuation is not straightforward in China. Low reliability of accounting figures and hidden liabilities that are only surfaced in detailed due diligence can make a substantial difference to the initial financial picture, so it is important not to get locked in to a valuation estimate too early on. Does the company possess the licenses it says it does? Does it actually own the rights and property it is purporting to sell? Particularly on the part of SOEs, there is considerable resistance to revising a valuation downwards, even when the legal position turns out to be different from what was originally represented.

In addition, targets may hesitate to commit themselves to any valuation for fear of having to account for it later. Again, this is particularly the case for managers of SOEs, who to avoid any possibility of later charges of selling state-owned assets at below market value may prefer a competitive auction for disposal. Investors should expect to spend significant time and effort explaining the transaction and ensuring that target managers understand what it entails. This is essential not only for valuation purposes but also to get the post-closing phase started in the right direction.

In a highly active deal market, investors should beware of the recurrent danger of entering into a transaction on the basis of limited information by the threat of it being passed to someone else. At a time when everyone wants to do deals and buyers outnumber sellers, this may be hard to resist – particularly when valuations may be partly guesswork. Despite the institutional downsides, prices in China are rising as entrepreneurs play investors off against each other and buyers begin to explore areas outside the main cities. As ever, accurate valuation depends on timing as much as the quantity and quality of assets and may only be confirmed by hindsight. The high price of an apparent bargain may only appear several years down the line, and the reverse can also be the case.

Post-Merger Integration

Closing a deal in China is cause for celebration. But it is a common mistake to assume it is the end of the challenge. In fact it is day one of a new and equally critical phase: ensuring the previous hard work in completing the transaction pays off by putting in place processes, structures and people who will manage and develop the enterprise on the ground.

The structure will already have been agreed. It is important to implement it correctly and to insist from the outset that agreed standards are adhered to in the running of the business. The pragmatic approach of Chinese owners towards risk, for example, will not be acceptable in the new venture. Raising the bar will be considerably easier if the investor has control and can manage the business in its own way up to international standards. Even so, it will still have to deal with local middle management and staff, and as with any acquisition managers will need to spend time communicating expectations, values and management principles that will apply going forward.

On the other hand, investors will frequently be working with Chinese partners in joint ventures where they do not have full control. This puts understanding the needs and viewpoints of the Chinese partner at a premium, and aligning the goals of both sides of the partnership is essential. Again, failure in the name of building trust to clarify issues around exit or continued business expansion, or what is negotiable and what is not, is likely to come back to haunt investors further down the line, sometimes even several years later.

Even assuming complete control, building a balanced management team in China presents challenges. While domestic managers are entrepreneurially oriented, they typically lack global experience. Now a steady stream of management returnees is beginning to supplement local talent with valuable international experience, but expatriates will often have forfeited the local networks and understanding of local markets that are another crucial ingredient in getting an operation up and running.

This means that management teams in China will require significantly more oversight and hands-on mentoring than in the case of an acquisition in the US or Europe. Particularly important is clear guidance in implementing corporate governance, financial reporting and other documentation and management processes.

In particular, as in any emerging market, investors need to factor in the cost of building robust financial functions from day one. As a deal closes, acquirers should ensure that they have the appropriate financial or financial control function in place. Failure to do so increases risk unacceptably. Even large quoted Chinese companies concede that they are as yet some distance from complying with international standards for internal controls and governance. Hard work on improving these processes at every level of the company is a first priority for attention in any Chinese transaction.

Industry Sectors

Automotive

With a recent growth rate of more than 30 percent a year, the Chinese vehicle market is the third largest and fastest growing in the world, making it a magnet for cross-border investment. From a base of extremely low ownership levels (just 0.5 percent of the population own a vehicle compared with 80 percent in the US), latest estimates are that by 2020 there will be 140 million cars on Chinese roads, seven times today’s total, while annual sales could rise from 4.4 million to 20.7 million units. China is expected to account for 30 percent of global market growth between now and 2010.

The Chinese auto industry is already the world’s fourth largest after the US, Japan and Germany. It comprises 128 producers, three of which (FAW, SAIC, and Dongfeng) are among the world’s 22 largest. In 2005, Nanjing Auto outbid the larger SAIC to take over the UK’s failed Rover group. Although Japanese and Western firms are well represented in China – Volkswagen’s partnership with SAIC goes back to the 1980s – the industry is attracting substantial further investment: under current plans, foreign car firms and their local joint-venture partners plan will invest US$15 billion to triple output to more than 7 million cars by 2008 (although VW has since announced a scale-back).

Until now the auto industry has been tightly regulated, with contradictory effects. On the one hand, since WTO accession prices have fallen and consumer demand has grown enormously, creating opportunities in ancillary markets such as repairs, replacement parts, petrol retailing, insurance and even valeting services. On the other, government intervention has held development back by confining foreign investment to joint ventures, compelling them to purchase components from local suppliers and using tariff barriers to shield the market from competition from imports. Productivity of foreign joint ventures is low compared with that of plants in Japan or the US, despite low labor costs.

Under the current industry plan, revised in 2004, the government intends to make autos a ‘pillar industry’ of the economy by 2010. Goals include consolidation to create five large and competitive automotive groups, coordination of industry and infrastructure to boost competitiveness, and the creation of powerful brands.

Some of the restrictions on foreign capital will be relaxed – JVs can be more than 50 percent foreign owned if producing for export – and tariffs will continue to come down as the government aims at self-sufficiency in production by 2010. Investors will be expected to bring in international-standard knowhow and technology, and to develop proprietary IP.

Vehicle exports, primarily to developing countries and the rest of South East Asia are anticipated to grow slowly, while parts sales, which totalled US$7.4 billion in 2004, are being sharply boosted as multinational assemblers seek low-cost suppliers to cut component costs. Visteon, the second largest US component maker, says it expects China to be its biggest market by 2010. Tenneco, another parts maker with five JVs operating in China, also recently announced a substantial expansion.

Financial services

The best strategy for cross-border entry into China is often to secure an industry position in the interim period of semi-liberalization before the full competitive free-for-all begins. This is the position in financial services, where foreign players have been fighting to gain a strong position before the sector is fully opened up under the second phase of WTO deregulation to foreign competition at the end of 2006.

In the last year foreign investors have done deals worth no less than US$18 billion with some of China’s largest state-owned banks:

• AmericanExpress, Goldman Sachs and Allianz, the German insurer, bought a 10 percent stake in Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), the nation’s biggest, for US$3 billion;

• Bank of America and Singapore’s Temasek invested US$4.1 billion in China Construction Bank (CCB);

• Royal Bank of Scotland, Merrill Lynch and Hong Kong’s Li Ka-shing took a US$3.1 billionn, 10 percent stake in Bank of China (BoC), the mainland’s second biggest lender, with another 10 percent going to Temasek for the same amount;

• HSBC spent US$1.7 billion on a 20 percent share of China’s fifth largest bank, Bank of Communications (BoCom). In addition Citigroup led a consortium bidding US$3 billion for an 85 percent stake in Guangdong Development Bank, which would make it the first foreign bank to gain control of a Chinese lender.

These are part of drastic moves to reform China’s banking sector which will turn the major institutions into joint-stock companies, reduce state shareholdings and introduce strategic overseas investors. They follow the flotation of three major Chinese banks, including CCB, in Hong Kong last year in IPOs which raised nearly US$15 billion and were among the world’s biggest of 2005. More are scheduled to follow, including a number of smaller join-stock and city banks which have already benefited from foreign investment. The intention is that overseas strategic investors will bring in not only capital, but even more importantly world-class management expertise, technology and corporate governance experience to enable them to compete with the foreigners when competitive restrictions are lifted at the end of the year.

There is a great deal riding on the reforms, for both sides. Since China opened up to the world in the late 1970s, the banks as government agencies have been almost wholly responsible for channeling China’s massive savings into industry and development, with results that can only be described as mixed. Chinese capital productivity is not nearly as high as it needs to be to maintain current growth rates, and much of the flow has ended up as non-performing and ‘special mention’ loans – an already huge overhang which would be greatly increased in the case of a property crash. Most NPLs have been moved into state-owned vehicles designed for the purpose, avoiding the worst, but the profitability of Chinese banks is still insufficient to generate the internal capital needed to support current levels of loan growth. Hence the need for overseas knowhow to boost the sector’s efficiency, transparency and governance. For investors, the attraction is access to China’s huge domestic market in savings, consumer lending, insurance and credit cards, particularly the last two:

• While consumer lending has been growing steeply, credit cards in China are in their infancy. McKinsey predicts exponential growth in this sector, with profits growing to US$1.6 billion by 2013.

• The Chinese insurance sector is characterized by low penetration and strong premium growth. Among emerging markets, it is the second largest after South Korea and the fastest-growing (more than 30 percent in 2003). At least 20 Sino-foreign insurance joint venture deals are currently in operation. With the elimination of the ‘iron rice bowl’ social security net and increasing geographical and product liberalization, both life and non-life sectors are anticipating continued strong growth in the years ahead.

Pharmaceuticals

China has for some time been a focus for the global pharmaceuticals industry. Currently ranked ninth largest drugs market in the world, it is expected to become the largest by mid-century. According to US-based researcher IMS Health, China was the world’s fastest-growing pharmaceuticals market in 2004, demand growing 28 percent to US$9.5 billion (official Chinese statistics put the totals much higher, probably as a result of different industry definitions). Provisional estimates for 2005 reflect growth rates of a similar magnitude.

Although per capita healthcare spending continues to be far below international levels, expanding demand is driven by population growth in general coupled with a rising middle class that is rapidly becoming both more health conscious and affluent and is expected to spend a higher proportion of its income on healthcare as it does so.

However, there is a vast gulf between the situation in the wealthier cities and the rural interior where healthcare provision is minimal and costs are almost entirely borne by individuals. To keep healthcare affordable for poorer citizens, the government is maintaining heavy pressure on pharmaceutical firms to restrain prices (drugs represent 60 percent of China’s healthcare spending, compared with 10-15 percent in OECD countries); in the last six years there have been 16 rounds of price cuts, saving consumers US$3.6 billion, according to one report. More cuts are anticipated.

On the production side, the industry is both highly fragmented and fiercely competitive: according to the Economist Intelligence Unit 70 percent of the market is shared by more than 5,000 domestic manufacturers. The top 10 control just one-fifth of the market, compared with up to half in developed markets. Unsurprisingly, the focus is on low-cost manufacturing, and R&D and quality levels are low. Counterfeiting is an endemic problem.

Foreign pharmaceutical firms are not new to China, some having maintained a presence for 20 years. Of the world’s top 25, 20 are already in place; in total an estimated 1,700 Sino-foreign joint ventures are estimated to be in operation accounting for investment of US$2 billion. Despite the already substantial foreign presence, however, observers believe that today’s circumstances and policies are creating new opportunities and incentives for market participation:

• WTO accession has reduced entry barriers and freed areas such as pharmaceutical distribution to foreign firms. While IPR and patent protection undoubtedly remain issues for multinationals, the authorities are beginning to respond to pressure from global watchdogs as well as the domestic industry to enforce patent rights and crack down on counterfeiters;

• The government is using both regulatory pressures and the threat of consolidation to raise industry quality and efficiency levels. It is counting on foreign knowhow and scale to boost R&D and help move the industry up the value chain. Multinationals are better placed to weather these and margin pressures, and are expected to take market share in the future.

Retail and consumer goods

Fuelled by a vast population, increasing spending power, and a rapidly expanding middle class, China’s booming consumer market is attracting renewed attention from foreign retailers eager to share in the country’s continuing growth. Although the consumer goods sector is already competitive in many areas (including consumer electronics, processed foods and others), the fast developing retail industry is being given a significant boost as China moves to implement WTO commitments, for example freeing investors from previous zoning and other restrictions. Since the end of 2004, limitations on number of outlets, ownership and geographical location of stores have been removed.

As well as by the freer operating environment, further retail development (particularly in the shape of hypermarkets, specialty stores and discounters, among others) is favored by:

• Fast growing consumption expenditure (currently 42 percent of the total) that is predicted to overtake GDP growth rates from 2007;

• An emerging middle class with a consequent move towards added value (higher product/service quality), more attractive shopping environments, increasing brand consciousness;

• Continued rapid movement from the cities to the countryside. 42 percent of Chinese now live in the cities, compared with 27 percent in 1990. Urban disposable incomes grew nearly 12 percent in 2004 to US$1,139. Sales tend to be concentrated in the coastal cities – in the top six (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Tianjin, Wuhan and Chongqing) total retail sales reached US$112 billion in 2004, making up one-fifth of the national aggregate. Attention is now beginning to switch to smaller cities with populations from 1-4 million, which offer large development potential;

• Low levels of consumer lending, which only began in 1997. Although take-up is rapidly increasing, credit cards currently account for just 0.3 percent of annual sales.

Foreign retailers are well represented in China – it is estimated that four of the world’s top 10 chains, 35 of the top 50 and 78 of the top 250 have opened stores there. Carrefour, Wal-Mart, Hoyondo and EK-Chor Lotus figure among China’s largest chains and have made the country a key supply source: Wal-Mart sources up to US$18 billion from China, Carrefour more than $3 billion. However, there is a long way to go. There were 302 foreign invested enterprises at the end of 2004 with a total of 3,903 stores. That compares with a country-wide total of 19 million stores, to which 800,000 new ones are added every year.

Energy

Although the sector is tightly controlled, Chinese energy in all its forms continues attract high levels of cross-border investment.

Fuelled by high economic growth rates and rapidly rising standards of living, Chinese energy demand is outstripping domestic supply. This, plus growing environmental concerns, makes oil, coal and gas a major strategic and domestic preoccupation for the authorities. As they try to assure supplies, increase efficiencies and modernize outdated facilities, there is a ferment of restructuring and consolidation under way, yielding opportunities for M&A and new joint ventures in major projects. To generate the vast funds necessary, stock- market conditions permitting a large number of IPOs of state-owned energy and utility companies are in the pipeline.

Two-thirds of Chinese energy is supplied by coal, of which China consumes 30 percent of the world’s output. It also has the world’s largest reserves. The industry is highly fragmented and inefficient, however, with many large concerns coming to the end of their working lives. To reassert control and boost production, the government is setting up 13 major production bases, covering 70 percent of total national reserves. Although reserves are plentiful and cheap (despite steady price rises since deregulation in 2002), there is a major concern with pollution. Cleaner coal technology will be greatly in demand going forward.

Although it accounts for just 8 percent of global oil consumption compared with 25 percent in the US, China consumed as much as 40 percent of the increase in global oil demand over the past four years and is now the world’s second largest importer. Demand can only grow as incomes rise and more households afford cars and energy-consuming household appliances. Heavily supported by the government, the Chinese national oil companies – the ‘Three Sisters’ – are themselves investing aggressively across borders. They are already in 12 countries – CNOOC is the largest producer in Indonesia – and have wider ambitions: CNOOC created publicity in 2005 by offering US$18.5 billion to take over US rival Unocal, a bid that was withdrawn after fierce US resistance to seeing strategic local assets acquired by a Chinese SOE. Under pressure from WTO and environmental commitments, the oil and petrochemical industries are also undergoing large-scale restructuring, with foreign investors encouraged to participate in exploration, large domestic infrastructure projects and downstream activities. Foreign companies too are eyeing up a share of China’s huge retail petrol market. However, hard bargains are being driven.

No foreign investors have signed up for a planned long-distance East-West oil pipeline, and drilling in the remote Tarim Basin, China’s last onshore field with untapped reserves, has generated little interest.

At the same time, China is seeking to make more use of natural gas, both by tapping domestic reserves and boosting imports, and we expect to see increasing emphasis on nuclear and hydroelectricity over the next two decades. Renewables are also starting to be exploited more widely in rural areas. As well as in the primary energy sources, we anticipate the emergence of deal opportunities in power transmission and distribution. The government invested US$31 billion in power generation in 2004, and a major effort is needed in parallel upgrading of the grid to cut waste and minimize outages.

Real estate

Real estate, in 2004 the second largest home for FDI in China after manufacturing, is currently at a crossroads. The underpinnings remain strong: the housing market is escalating as more of the population aspires to graduate from state-allocated dwellings to home ownership, and demand for commercial property of all kinds continues to expand along with the economy.

Backed by a ready supply of credit, until last year prices were increasing sharply: average real-estate prices over the country rose more than 14 percent in 2004 and considerably faster in cities such as Shanghai which were the recipients of a flood of ‘hot money’. According to the central bank one-quarter of the money used to buy houses in Shanghai came from abroad, and more than 17 percent of housing in Beijing was bought for rental or resale.

Following a central bank warning last year of the dangers of a property bubble, the government has since taken action to moderate the boom, tightening credit, raising interest and mortgage rates and imposing a sales tax on property sold within two years of purchase. As a result, sales have slowed, prices fallen back sharply and buyers retreated to the sidelines in anticipation of further price falls.

However, the retreat has caused its own problems. As much as 50-60 percent of units in new developments may have been bought by speculators, many betting on the revaluation of the Chinese currency by taking out dollar-denominated loans from offshore lenders. At the same time, in the rush to get buildings up, developers have resorted to a number of dubious financing methods, including securing large bank loans by lining up employees and others as fake buyers, in the expectation of being able to resell after construction began. Last year the central bank said that ‘false mortgages’ substantially increased the risk of a property bubble, with risks not only for developers but also the banks, which ultimately shoulder the lending risk.

Venture capital and private equity

Venture capital investment in China has been increasing sharply in recent years in both scale and scope. From US$418 million invested in 226 companies in 2002 totals grew to US$1.27 billion and 253 companies in 2004, making China the fifth largest market in the world after the US, Canada, Israel and the UK. Existing foreign and local VCs have been joined by new entrants persuaded that a China strategy is essential as a cycle of investment and successful exit, corporate activity and overall economic growth takes hold. China is seen as the only country outside the US that can support the creation of extremely large companies in a purely domestic market, while venture-backed IPO and M&A deals are proving that profitable exits are possible, albeit on foreign exchanges rather than domestic ones. 2004’s 21 venture-backed Chinese IPOs raised US$4.3 billion and included four of the top 10 global technology offerings, and the trend continued in 2005. IPOs included the spectacular launch of Baidu, the Chinese search engine firm whose stock soared a record 350 percent on NASDAQ in August. In M&A, Yahoo’s US$1 billion investment in Alibaba.com, an auction site, is also notable.

The bulk of venture capital in China (65 percent) is accounted for by foreign firms, whose market share continues to rise as new investors move in, attracted mostly to Shanghai (with a cluster of fast-growing media, semiconductor and internet-based firms) and Beijing (IT, software and communications). Foreigners are increasingly establishing a China office to pursue business development for home country portfolio companies and/or source deals. Some foreign firms are targeting teams of returnees from Western countries. Domestic operators are handicapped by a regulatory framework that holds back capital formation in-country and smaller funds – the average foreign fund of US$200 million is seven times larger than its local counterpart.

Although in general the future for venture capital in China is bright, challenges still abound. Sourcing deals takes time and effort, and experienced Chinese managers are thin on the ground. While the regulatory environment has improved substantially, the infrastructure is immature and held back by weak IP protection. Regulatory interference is diminishing, but can still have unpredictable effects: a ruling by China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) last year designed to close a tax loophole led to a temporary fall in VC financings as it effectively made an IPO on a foreign exchange harder to achieve. The ruling has since been reversed and deal flow has resumed.

With confidence underpinned by vigorous growth in M&A and IPOs, private equity is also burgeoning in the China market as buyout houses rebalance their regional emphasis. Notable deals in 2005 included Carlyle’s US$410 million investment in a 25 percent stake in China Pacific Life Insurance, one of the biggest mainland private equity transactions to date, and the same group’s acquisition of an 85 percent share in Xugong Group Construction, a heavy industry group, for US$375 million. In June, CVC Capital Partners announced a US$2 billion Asian buyout fund, and other specialists such as KKR are also reported to be raising large amounts of fresh capital for the region. PE targets include fast-growing companies in telecoms, media, IT and increasingly retail. Plans by the currency regulator to lower hurdles for foreign institutional investors seeking approval to buy domestic stocks and possibly making it easier for private equity investors to repatriate profits are likely to increase the invasion, with the offsetting effect of increasing competition for deals. Although the government is happy in principle to see SOEs brought under the discipline of shareholder value, it remains to be seen how free PE acquirers will be to manage their purchases – gearing them up with debt, for example – as they do in the more developed markets.

In Summary

Although China remains a market unlike any other, the differences and difficulties in concluding satisfactory deals are slowly dimishing. On the one hand, foreign firms and experienced advisors are getting better at navigating the challenges; on the other, WTO commitments and the need to develop lasting trading relationships with outsiders are gradually bringing more sectors into line with business practices that are recognized in other parts of the world.

Some of the frustrations remain: the constant need for bureaucratic approvals, conflicting aims between different levels of government, and the ambiguity of the legal system. Even where central government is pressing for reform, the strength of local vested interests can often frustrate it. At transaction level, deals are still time consuming and effortful to close, valuations may be hard to agree on and joint ventures meet the barrier of Chinese reluctance to cede control. Differentials between city and countryside and the lack of democracy are building up political pressures that may be difficult to manage.

Yet there are also important positives. The Chinese are natural capitalists (even though the word is still taboo). The power and consequences of economic growth, once unleashed, are almost impossible to reverse – or sometimes even rein in, although the government has so far done a reasonable job of taking the heat out of the property boom, for example.

The abnormal dependence on relationships is diminishing. Above all, having pinned its faith in economic growth, China knows that to sustain the momentum its population expects it has no alternative but to pursue sustained cross-border investment and alliances to modernize its state-owned firms and bring them up to world standards of efficiency and governance. China needs foreign firms for technology and know-how, just as foreign firms need China for growth. That is not to say that foreigners will be allowed to take control and walk off with all the rewards. Hard bargains will continue to be driven. But assuming the strategic rationale for China entry holds up, we believe the key question for most large Western companies is no longer ‘if ’ or even ‘when’, but ‘how much’. That is, going into China is a matter of good advice, professional due diligence and careful negotiation. It is no longer a black box or a leap in the dark.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter