Publications Habits Of The Busiest Acquirers

- Publications

Habits Of The Busiest Acquirers

- Bea

SHARE:

By Robert N. Palter, Dev Srinivasan – McKinsey & Company

M&A executives at the most successful US companies understand not only how acquisitions create value but also how to enlist the support of the organization.

A thin line divides the kind of merger that nurtures a company’s growth from one that destroys value. No surprise, then, that M&A practitioners go to great lengths to tilt the odds in their favor. They hire world-class M&A teams, modify the organizational design of their companies, or add systems, tools, and processes to smooth integration and to accelerate the capture of synergies. Yet a merger’s performance over time is subject to so many variables that it’s difficult to analyze whether such moves really work.

To unearth the practical insights that can help companies succeed in planning and executing acquisitions, we went directly to the executives most responsible for overseeing M&A at the top US acquirers. Over the course of 20 interviews with business-development officers, we explored their thinking on what does and doesn’t work in M&A. Then, to see what companies rewarded by the capital markets were doing differently, we compared the different approaches of these companies with their general performance during an active period of acquisitions.

Our findings provide a road map for the way companies should think about and execute acquisitions to improve their odds of success. We found, for example, that development officers at most of the rewarded acquirers tend to treat M&A as a tool to support strategy, not as a strategy in itself. Moreover, they use M&A to complement a company’s distinct capabilities. They understand the limitations of acquiring a company in order to acquire its superior management or operational know-how. And to implement the details of integration, they involve individual business units in different ways, depending on the type of merger.

One lesson from the experts clashed directly with conventional M&A lore: world-class M&A teams made up of former investment bankers and lawyers are not a differentiator of performance. Companies with talented M&A teams are as likely to be rewarded by the markets as not. Moreover, talented teams are fairly common, and the professionals who belong to them are abundant. Instead, the tenure of an executive was a differentiator; companies with longer-tenured executives during a period of acquisitions were more likely to be rewarded. Other necessary factors — including organizational design, people, systems, tools, and processes — are insufficient without a solid approach to acquisitions and integration.

M&A is a tool, not a strategy

Many companies act as though acquisitions are their growth strategy. These companies acquire repeatedly for the sake of top-line growth, without a clear plan to capture additional growth once the target is integrated and synergies are captured. An acquisition can be a powerful builder of short-term value for these companies, but they inevitably falter as the number of value-creating targets declines or as they bump up against regulatory hurdles. Investors quickly realize when companies reach the end of their potential to grow through acquisitions — stock prices then sag, reflecting anticipated slower growth.

Executives at companies that reaped market rewards insist that M&A shouldn’t be a strategy on its own

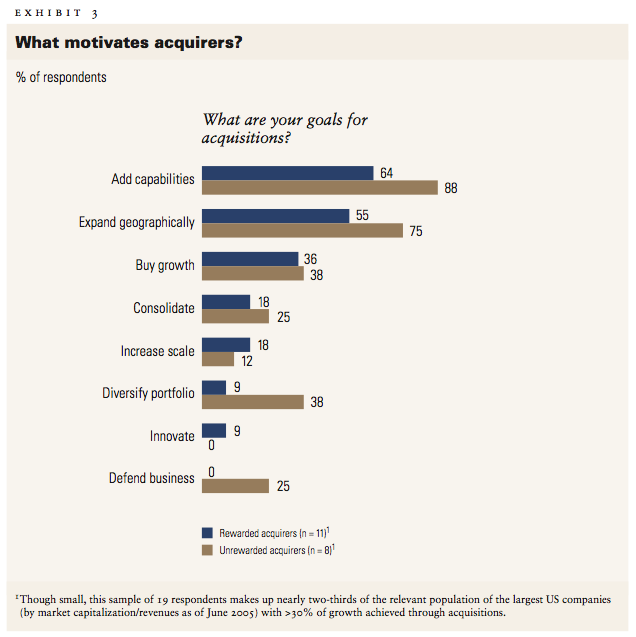

The business-development executives we interviewed had similar motives (including adding capabilities, expanding geographically, and buying growth) for their acquisitions. Yet the executives at companies that reaped market rewards insist that M&A shouldn’t be a strategy on its own. Instead, it ought to be a tool to fill strategic holes (such as diversifying an asset profile or expanding a geographic footprint) that can’t be filled as efficiently on an organic basis. As a strategy executive at a consumer goods company told us, “Once the corporate strategy was settled, we’d look for opportunities, both organically and through M&A, to pursue that strategy. We were not simply out fishing for good acquisition targets; we were executing a strategy.” The connection between successful acquirers and their adherence to an over-arching strategy is also shown by the fact that none of them acquired companies for defensive purposes — that is, to block a competitor. For these companies, it would seem, M&A strategy is proactive rather than reactive.

This observation isn’t meant to downplay the importance of acquisitions in overall company strategy. When used correctly acquisitions are a necessary part of a large company’s growth — indeed, recent McKinsey analysis shows that many large companies generate more than a third of their long-term growth through acquisitions. However, acquisitions should be viewed within the context of the overall corporate strategy.

One high-tech company, for instance, used a combination of acquisitions and organic growth to pursue its twin strategic goals: reducing costs and becoming the leading US company in its industry. Pursuing its goals only organically would have taken too long because it needed an immediate nationwide presence to capture market share during the early stages of the industry’s growth cycle. In any case, the cost of growing organically would have been extremely high. A partnership would meet the company’s time constraints but deliver just a fraction of potential profitability. In addition, neither organic growth nor a partnership would help the company lower its costs.

A merger or acquisition, by contrast, would quickly and profitably offer the company the nationwide presence it sought, along with the potential for significant cost synergies. The company’s eventual no-premium merger with a competitor created value equaling nearly half the cost of the merger. One of the keys to success was the combined entity’s ability to drive organic growth, which nearly doubled in five years.

Contrast this long-term success story with the experience of a financial-services firm that relied almost entirely on acquisitions to fuel its growth in the 1990s. The company’s stock skyrocketed as it captured all the synergies, and it significantly outperformed its peers. However, hidden in the massive top-line growth and market appreciation was the fact that the company was devoid of organic growth.

As fewer and fewer accretive acquisition opportunities remained, the company’s share price declined. Since then, its shares have significantly underperformed those of its peers, partially because its underlying organic growth rate has continued to be lower than that of the economy as a whole.

One high-tech company, for instance, used a combination of acquisitions and organic growth to pursue its twin strategic goals: reducing costs and becoming the leading US company in its industry. Pursuing its goals only organically would have taken too long because it needed an immediate nationwide presence to capture market share during the early stages of the industry’s growth cycle. In any case, the cost of growing organically would have been extremely high. A partnership would meet the company’s time constraints but deliver just a fraction of potential profitability. In addition, neither organic growth nor a partnership would help the company lower its costs.

A merger or acquisition, by contrast, would quickly and profitably offer the company the nationwide presence it sought, along with the potential for significant cost synergies. The company’s eventual no-premium merger with a competitor created value equaling nearly half the cost of the merger. One of the keys to success was the combined entity’s ability to drive organic growth, which nearly doubled in five years.

Contrast this long-term success story with the experience of a financial-services firm that relied almost entirely on acquisitions to fuel its growth in the 1990s. The company’s stock skyrocketed as it captured all the synergies, and it significantly outperformed its peers. However, hidden in the massive top-line growth and market appreciation was the fact that the company was devoid of organic growth.

As fewer and fewer accretive acquisition opportunities remained, the company’s share price declined. Since then, its shares have significantly underperformed those of its peers, partially because its underlying organic growth rate has continued to be lower than that of the economy as a whole.

Involving business units

The integration phase of an acquisition is often the time when deals go wrong; some studies blame poor integration for up to 70 percent of all failed transactions. According to the vast majority of acquirers we spoke with, the responsibility for integration falls to the business units. Not that they are to blame for all of the widely publicized failures, but in the words of one business-development executive, “Our biggest challenge is to make sure that the corporate M&A team and business unit executives work in concert on an acquisition” — an important insight. Acquirers generally try to ensure this kind of collaboration by using documented procedures that make everyone aware of their own and others’ responsibilities, as well as tools to track the progress of the integration effort.

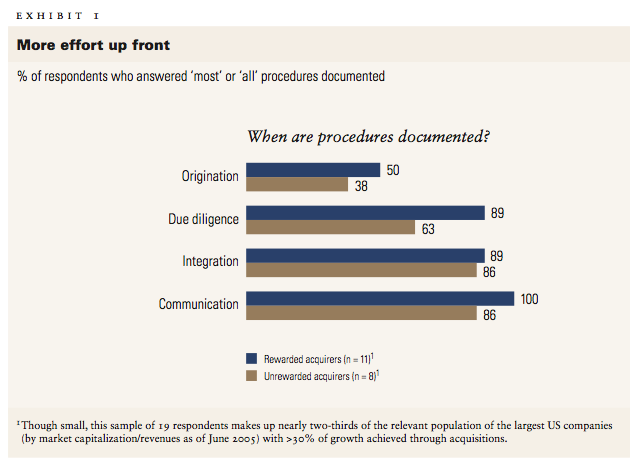

However, rewarded acquirers do so much earlier in the process, particularly in the due-diligence phase (Exhibit 1). Also, their procedures are generally better documented overall than those of the unrewarded acquirers.

How and when should individual business units become involved? It depends on whether the type of transaction a company pursues falls within or outside its existing operations. At rewarded acquirers, the business units were heavily involved in transactions for “bolt-on” acquisitions — those within the realm of a company’s existing operations — during the origination and integration phases. Furthermore, rewarded acquirers were more than twice as likely to involve their business units in acquisitions from start to finish, including origination, due diligence, negotiation, and integration.

Indeed, while the M&A team’s involvement is essential for ensuring that all transactions are pursued rigorously, an M&A team that identifies synergy opportunities without significant participation by the relevant business unit can engender resentment and bring about charges that the team is setting unattainable targets. Many rewarded acquirers therefore say that having business units lead the entire process for a bolt-on acquisition can dramatically improve estimates of synergies — and the likelihood of capturing them.

In particular, the rewarded acquirers involved their business units during the due-diligence phase. Some of them formally organized teams consisting primarily of high-level business unit executives, members of the M&A and legal teams, and other experts as warranted (for example, tax accountants or environmental experts). Rewarded companies typically charge such teams with the responsibility for driving the process through to integration. During the due-diligence phase, they are especially active in identifying and quantifying opportunities and risks.

Unlike unrewarded acquirers, which tend to look outside the organization for M&A talent, rewarded acquirers are more likely to promote from within. Although M&A executives in both groups had similar levels of tenure in their present positions, M&A executives at rewarded acquirers had significantly more experience at their companies, albeit in different roles (Exhibit 2). The fact that an M&A executive at a rewarded acquirer has a deeper knowledge of the culture, people, and capabilities of the company undoubtedly helps the executive to navigate corporate politics and identify targets that truly address a company’s needs. It also ensures support from key people in the business units.

For “transformative” transactions — those involving acquisitions outside the realm of a company’s operations — the most rewarded acquirers typically ask M&A teams to take the lead in bringing the acquirers’ core capabilities into new industries. The involvement of business units in such acquisitions is quite low. Deals are originated primarily by the M&A team, which often has a better position than the leaders of business units to think up game-changing ideas. As one executive said, “In origination, the guiding principle is to ‘get ideas.’ I’d tell my team to get out of the office and find the new ideas. Our job is to get transformative, game-changing growth.”

Still, in certain situations, it makes sense to involve business units in transformative acquisitions. An executive at one rewarded acquirer said that his company had been looking to transfer its distinctive distribution capabilities to related industries. The deal’s success hinged on the ability of the acquiring company’s sales force to sell the new products to current clients. Although the sales force had only a limited knowledge of these products, involving it in the transaction from start to finish helped the acquirer to quantify potential revenue synergies, to minimize the loss of clients during the transition, and to keep salespeople fully committed to selling the new products once the acquisition was complete.

Understanding limitations

Often, when a company faces declining margins or market share or other difficulties in its core operations, it tries to solve these problems by acquiring a better-performing competitor with greater capabilities. Such an acquirer thinks it can buy the competitor’s know-how and management and apply them to its own operations and thereby improve its performance.

While this logic seems reasonable, it can be dangerous. In our experience, it’s very difficult for an underperforming acquirer to improve its performance dramatically by acquiring a leading competitor and extracting its capabilities. Unfortunately, unrewarded acquirers are much more likely to take this approach. Many executives at such weak performers told us that the primary intent of their acquisitions was to import the target’s best practices to their own company. Unrewarded acquirers may also be expecting too much from M&A; when asked to choose from a list of possible motives for pursuing an acquisition, they picked an average of three, compared with only two for rewarded acquirers (Exhibit 3).

One national retailer, for instance, attempted to augment its weak geographic coverage, poor store conditions, and inferior merchandising strategies by acquiring another retailer in the hope that the target’s strong management team could turn around its own fortunes. The market clearly disapproved. Analysts immediately pointed to the target’s negative sales and margin trends and questioned the generous premium paid by the acquirer. Investors shaved nearly 5 percent from its share price. In one executive’s candid assessment, the target company turned out to be a laggard that offered little to the acquirer. Buying it for its human capital was a major failure, and now both entities are struggling.

This isn’t to say that companies should never acquire a target for its capabilities. Indeed, all of the high-performing acquirers we spoke to had executed such transactions and explicitly regard them as a tool to fill small but important capability gaps. The difference may be that rewarded acquirers look for acquisitions that supplement their unique characteristics, capabilities, and assets. They also search for targets that would benefit from their distinctive strengths. One corporate executive summarized his company’s acquisition strategy simply: “We look at what we’ve been able to do better than the competition — and get more of it through acquisitions.”

In practice, this perspective makes it critical to scan for opportunities at a very detailed level during the due-diligence phase rather than focusing on operating metrics or building a financial model that estimates accretion or dilution or the internal rate of return. Take the experience of a transportation company with a record of more than ten sizable transactions during the past five years. Its due-diligence team scans transport routes, mile by mile, from top to bottom, looking for opportunities to sign up new customers or to become more efficient by changing routes and thus to make the very best use of its own capabilities. This level of detail, though generally difficult to achieve in the short time period of an acquisition, can yield powerful benefits.

Companies that have consistently added value through their acquisitions share some practices that may explain their success. They balance acquisitions with organic growth, leverage the entire organization to drive the process from start to finish, and understand how they can use their own strengths to create a competitive advantage.

The authors wish to thank James Shilkett for his contribution to this article.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter