Publications Mergers And Acquisitions: Reducing M&A Risk Through Improved Due Diligence

- Publications

Mergers And Acquisitions: Reducing M&A Risk Through Improved Due Diligence

- Bea

SHARE:

By Jeffery S. Perry, Thomas J. Herd – A.T. Kearney

“The art of doing due diligence is being lost. Buyers aren’t analyzing the operations and books of prospective acquisitions with nearly enough vigor” (Fortune, 3 September 2001).

For the past few years, sad stories of gigantic merger failures have been told and retold in the media – for example, the painful sagas of AOL Time Warner, Corus, and Vodafone. M&A veterans trade excruciating war stories among themselves about a multitude of smaller, less notorious disasters. What went wrong with all these deals? In trying to answer that question, analysts have scrutinized and interpreted gigabytes of information. Their conclusions: M&A failure can be attributed to poor synergy, bad timing, incompatible cultures, off-strategy decision-making, hubris, and greed. But one universal lesson has become obvious: making a deal “work” is one of the hardest tasks in business.

Between recognizing the potential value of a merger or acquisition and achieving a new and fully integrated enterprise is a dangerous middle ground where anything that can go wrong will. Early on the buying company needs to fully understand exactly what it’s getting and what it’s getting into. As mergers and acquisitions become increasingly complex, the activities of due diligence become ever more important. The danger is not that companies fail to do due diligence, but that they fail to do it well. The good news is that a handful of due diligence best practices can reduce the risk and give the deal a fighting chance.

Risk on the rise

Although the number of mergers and acquisitions has declined over the past two years, the deals that are being struck are far riskier than those of the 1990s. The increasing risk can be traced to at least three converging trends:

1) Companies in maturing industries are rebalancing their portfolios, or selling off pieces of the business. Companies that acquire these pieces must ‘untangle” the target’s business processes from its parent company; in many cases, the pieces being sold have entrenched processes and cultures that are difficult to integrate into the buyer’s organization.

2) Cross-border transactions – increasingly common because of the global reach of today’s industries – are intrinsically riskier than those within a single country.

3) Expectations have changed. In the 1990s, a merger or acquisition was expected to deliver cost reductions. Now, M&A is often a core growth strategy as well. Achieving projected growth targets is far less certain than achieving projected cost savings – and more difficult to measure.

Despite the waning number of successful M&As, history reminds us that consolidation is inevitable. However, new accounting rules mean the game will not be played in the same way. Acquirers will have to explain in more detail the reasons behind an acquisition. Boards of directors and investors will demand a more thorough assessment of potential targets, and acquisitions will take place only when there are identifiable, quantifiable operational synergies. CEOs will be motivated to prepare for the acquisition well beforehand, when it is still an idea. The ideal acquisition will begin by pinpointing a target that the acquirer can ‘fuse” with and end with a well-managed integration execution – the skillful management of initiatives, projects and risks, and the limited loss of customers and talent.

The inescapable reality is that buyers must perform better upstream planning. If a purchasing company does not gain a full perspective of the potential partner prior to the acquisition, realizing value from the deal will be nearly impossible.

The perils of M&A

Historically, half of all M&A activities have failed to create lasting shareholder value. Findings in a ten-year A.T. Kearney study on stock performance after mergers reveals that since 1990, in the two years after their deals closed, nearly 50 percent of the biggest mergers and acquisitions failed to produce total shareholder returns greater than their industry peers. Only 30 percent outperformed their industry peers by 15 percent or more) and had earned a penny more in profitability two years later. After five years, 70 percent of the survivors were still chronic under performers in their industries.

Follow the leaders, learn from the failures

In recent years, a few companies have demonstrated exceptional proficiency in assessing their target acquisitions – evaluating them as stand-alone organizations and then factoring in the value of any potential synergies between them and their new partners. Cisco Systems is a good example. Throughout his acquisition spree of more than 70 companies, CEO John Chambers avoided large-scale employee turnover and successfully leveraged the acquired firms’ products and technologies. Kellogg’s is another example of a skillful M&A executor. A year after it acquired Keebler Foods, Kellogg’s rewarded shareholders with a 25 percent return. Another exemplar, General Electric bought 534 companies in six years without much fuss. Such stories of skillfully managed mergers rarely make a splash in the media – but there is no doubt about their impact on long-term shareholder value.

Granted, few of these deals were complex “mergers of equals”, but speed and success were achieved mainly by thoroughly integrating the target into the acquirer’s business processes and by employing well-defined and time-tested integration practices.

Unfortunately, most companies are not so adept. They buy companies without understanding exactly what they are getting. They underestimate integration and deal costs, overestimate savings, and imagine synergies that do not exist. Shortly after the now-failed merger of AOL and Time Warner, the new CEO, Richard Parsons, said the synergies ascribed to the deal were oversold. “Time has not even been able to get its AOL email to work properly”, he told Newsweek. Two years after Vivendi‘s acquisition of Seagram‘s entertainment business, there was scarce evidence of synergies between the company’s US and European assets. And the merger between British Steel and Hoogovens in 1999, which formed Corus, was supposed to create one of the largest steel companies in the world with a US$6 billion market capitalization. Today, the business is worth a mere US$250 million.

In hindsight, these companies did a poor job of planning. They failed to identify the risks in integrating two organizations with very different management and operational processes. The results were predictable: management strife, political interference, employee rebellion and disastrous financial results.

Turning the odds in your favor

Ensuring that an acquisition is a good fit, not just on paper but as an integrated business, calls for going beyond performing traditional financial due diligence to performing a detailed value assessment. We call this a pre-assessment or “improved due diligence”. It takes place prior to signing a memo of understanding (MOU) and includes examining both operational and management issues and risks. The insights gained are used to value the target, communicate to the board of directors, create a bidding strategy, plan negotiations, and accelerate the integration of the target company.

This early analysis provides a comprehensive perspective of the acquisition’s potential to create lasting shareholder value, and should influence how the market reacts to the acquisition announcement. In our experience, it is possible to isolate winning acquisitions at this very early stage because the top acquirers tend to share common characteristics. The following offers our perspective on four ‘best practices” that separate the winners from the losers in the M&A playoffs.

1. Winners: call on the experts

To get beyond the numbers and challenge traditional assumptions about risk and value, winners pull together expert resources (both internal and external) that understand base business value and growth, and can evaluate cost and revenue synergies.

For example, as a spreadsheet exercise, valuing a target’s base business is relatively straightforward. What acquirers often miss in their number-crunching process, however, is spotting problems in the target’s base business. These are usually not apparent from routine inspections of publicly available documents and will not be readily disclosed by the target company.

Another common mistake is failing to assess the target’s future growth rate and profitability and then neglecting to “sanity” check the findings against changing conditions in the macro-economic, foreign exchange and competitive environments. Needless to say, forecasting an unrealistic growth rate for the target can have dire consequences on its valuation. If the base business is overvalued by 20 percent, an accurate evaluation of potential synergies will be of little comfort.

One way to manage these issues is to reach out to experts who have experience working through this maze. Interviews with third-party industry or trade experts, customers, or suppliers are also helpful if they can be done discreetly and out of public view. These people should be able to offer objective information about the quality of the target’s business, its executive talent and workforce, processes and products. For example, if a target company has a poor history of bringing successful new products to market, the acquirer has the right to be skeptical of its positive claims about an upcoming product launch. Or if the company has a history of under-investing in R&D, physical capital or maintenance, the acquisition business case should anticipate and plan for increased investment in these areas. This will ensure reliable product supply and head-off sudden unexpected increases in operating costs.

In evaluating cost and revenue synergies, many companies struggle with striking the right balance between the two. They place too much emphasis on cost synergies and ignore those that will point to future growth. Or they overestimate growth potential and miss the short-term value that comes from improving efficiency. That’s because analyzing synergies beyond financial statements is complex – opportunities can cross functions, product families and processes. But sorting through the complexity is worth the effort. An acquisition that gives appropriate weight to cost and growth synergies is more likely to succeed.

Again, for this effort, the top acquirers call on experts who have experience in helping companies identify and realize cost and revenue synergies (see box “Inside Cadbury‘s sweet deal”). They include their internal experts in the analysis process as well. Sales, marketing and operations people should always be part of the value assessment because they are the people who are typically charged with, and held accountable for, integrating the two companies after the deal is signed.

Sun Microsystems does this well. Sun involves its sales and marketing team at the beginning of every potential acquisition to analyze the to-be-acquired products of the target. The team explores the possible risks related to the products, including: their success rate to-date, projected growth in customer demand, “fit” with other products in Sun’s portfolio, and the likelihood that the products will enable Sun to expand its presence in desirable geographic, technology, or industrial markets.

Also, by assessing potential synergies beforehand, a buyer can quantify the likely costs to implement the acquisition (both expenses and capital), and estimate the time it might take to realize the benefits. Both will influence how much the acquirer should pay for the target. With today’s constant refrain from investors to “know what you are getting into”, this value assessment will help identify the target’s viable potential. Essentially, it offers insight on the true net value of the deal, which confers an advantage at the negotiation table.

Inside Cadbury’s sweet deal

For years, growth for Britain’s Cadbury Schweppes, a multi-billion dollar confectionery and beverage company, had always been accomplished the same way. The company made small “bolt on” acquisitions of regional brands. These acquisitions were not complicated; they did not require a sophisticated M&A process, nor did they trigger significant integration challenges.

But to compete globally, Cadbury needed to make a big move that would thrust it into the ranks of its major competitors. It targeted Adams, a confectionery company first owned by Warner-Lambert and then Pfizer. Adams produces and markets three gums – Trident, Dentyne, and Bubblicious – plus Halls lozenges, Certs breath mints and other popular brands. With Adams in its portfolio, Cadbury would become the number two global gum maker (behind Wrigley) and enter a new segment – functional confectionery, which includes sugarless gum and breath mints – a segment growing at nearly twice the rate of the broader confectionery category.

The Adams pursuit in 2002 was different from anything Cadbury had ever attempted. It was valued at more than US$4 billion, it was cross-border (Adams was based in New Jersey), it was a “carve out” that would require untangling of support services and business processes from Pfizer. Unlike a bolt-on, this acquisition would have to be integrated into Cadbury’s existing regional confectionery businesses. At the same time, the company would have to clean up the problems from previous bolt-on acquisitions – a major risk factor of the deal.

With so much at stake, the company could not rely solely on financial due diligence. The executive team wanted to look at the key operational and management drivers that would affect the success of the acquisition. And Cadbury needed to have a high degree of confidence in its valuation of the target, since competitors, all with deeper pockets, would also be bidding on the Adam’s business.

With little experience in acquisitions of this scale, Cadbury sought out subject matter experts, including A.T. Kearney, to determine the deal’s potential value. The experts ran workshops to determine synergies, developed action plans and identified other sources of value. All were documented and incorporated into the company’s acquisition case, greatly improving management’s confidence in the acquisition model’s rigor and accuracy.

Cadbury also needed to address the risk of business disruption that could result from “decoupling” the Adams business from Pfizer’s infrastructure. One step was to help Cadbury challenge assumptions around how much transitional back-office support would be required from Pfizer post-closing. Another was to identify ways to simplify and speed up the untangling process while reducing Adams’ reliance on Pfizer for basic services.

Armed with a rich perspective, including an eyes-open understanding of integration risks, Cadbury was confident in its valuation of the target and was successful in the auction with a US$4.2 billion bid – a more aggressive bid than both the market and competitors had expected.

The story did not end here. After Cadbury won the deal, the de-risking process continued well into the merger integration. Key members of the valuation or “deal” teams stayed involved to ensure that knowledge gained during the enhanced due diligence process was used to develop and execute the pre-integration plan. This allowed Cadbury to “ip the switch” upon signing the deal, and have a perfect “day one” with no business disruption.

2. Winners: trust but verify

Decoupling the acquired unit’s business processes from its parent’s is tedious work that usually produces little or negative net synergy value. To close the deal, sellers tend to make soothing promises about their efforts (already underway) to untangle the unit from its core business, and many executives will pledge to remain available to assist with the process throughout the integration. It’s tempting to take these assurances at face value and refocus your attention on more strategic and value creating activities within the deal.

But being lulled into complacency can be a huge mistake. The unbundling process can be disruptive to the acquired unit and harm the value of its base business. We have seen damage caused by missed orders, poor production planning, poor customer service, and even difficulties in billing the customer and collecting payments. As in organ transplant surgery, a divested business must be cut away from its host and quickly reattached to the acquiring company’s business processes before its vitality ebbs.

One complicating factor is that the parent company usually has little incentive to help with this operation. Despite the promise to remain available, managers in the parent company are more concerned with running their remaining businesses. The parent managers will likely be paid a fee by the acquirer to continue to provide basic back-office services throughout the 6- to 24-month transition period; but providing services at historic quality levels will likely be a low-priority.

Buyers can gain some leverage by including performance thresholds into any service agreement with the seller and then aggressively monitoring the seller’s performance. We have seen clients reduce their service payments by millions of dollars just by challenging the numbers against both the market value of the services provided and the seller’s own use of resources.

3. Winners: focus on what matters

In most deals, success hinges upon getting a few things right – the details that will drive the overall value in the deal. These might change from deal to deal but may include such common initiatives as creating an aggressive market penetration strategy, devising an innovative plan for product launches, realigning the sales force, rationalizing the supply chain network and IT applications, and creating a shared services organization.

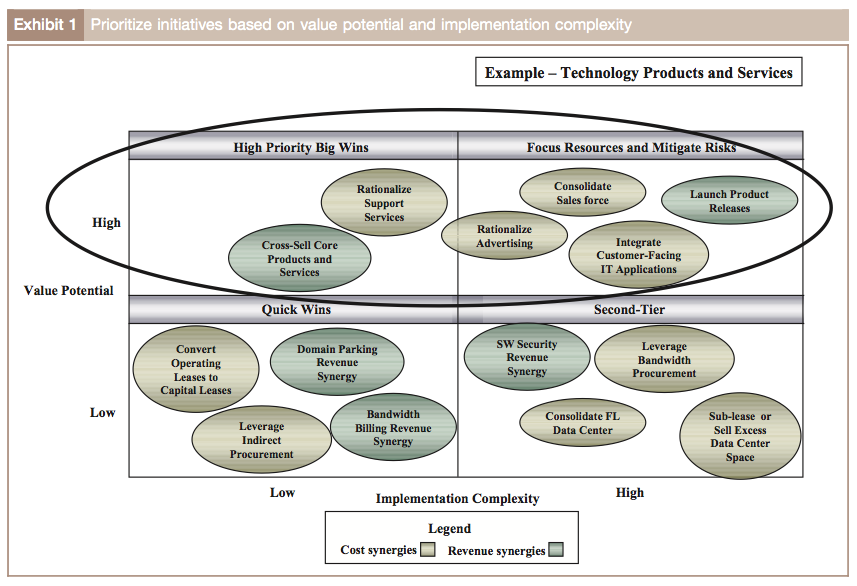

Of course, these initiatives cannot be managed in the same way. Each has to be prioritized according to the value it brings to the deal, and the complexity of implementation. Exhibit 1 shows a matrix used by a high-tech company to prioritize the primary initiatives of an upcoming acquisition. Some of the initiatives were high value but relatively less complex – so the plan for these was to aggressively capture this value. Other initiatives were high value but more complex. For these, the plan was to make sure that resources were focused and inherent risks were managed.

Once the high priority/complex initiatives have been identified, their associated risk factors must be considered. The job of mitigating risk will fall to management and require a plan of attack based on the potential impact of all risk scenarios (see Exhibit 2). Success will depend on determining both the probability of a major risk occurring and the impact if it does. At this stage, prior to an announcement, it is best to use a simple scale for assessing probability and impact rather than a more complex metric system. The managers of each initiative can then formulate risk mitigation plans to lower the potential of each risk factor. The mix of effort spent on reducing the frequency of occurrence versus the impact of occurrence will differ for each initiative, but a good rule of thumb is to focus first on minimizing the more dangerous of the two.

For example, an acquirer that wants to penetrate new markets may have to retain key talent in the target company – the brain trust and channel experts needed for long-term industry dominance. The company will determine what compelling incentive programs (a type of risk mitigation plan) are needed to encourage their best and brightest employees to remain with the company until its integration goals are met.

In a traditional due diligence process, employees’ talent and skills would never be included in the calculation of value. But in a risk-driven process, the acquiring company knows that the value of the acquisition plummets if top people leave. Of course, the acquirer could spend all of its risk mitigation efforts on training its own team to run the acquired ®rm. But it is more efficient to minimize the probability of flight risk.

Consider the experience of one privately held company. In negotiating an acquisition with the founder of a technology-based manufacturing firm, the acquirer neglected to secure the commitment of the founder and his key staff to remain and run the company. The result was a hefty transfer of cash into the founder’s pockets, and an immediate loss of value and business viability for the acquired company once its leadership team headed for the exits. This costly situation could have been avoided with the right questions during negotiations, followed up by appropriate incentives or non-compete agreements. The founder and his staff simply wanted an opportunity to “cash out” and had no intention of working within a larger enterprise.

Bottom line: customers and employees of the target company can vote with their feet as soon as a deal is announced. Communication to these groups must begin immediately to secure their loyalty and buy-in. The time between signing and closing, whether it is measured in weeks or months, can then be used to fine-tune and begin to rollout risk mitigation plans.

4. Winners: orchestrate the unveiling

With so much riding on making a favorable first impression, it is surprising that more acquirers do not place more emphasis on planning for and orchestrating the public birth of the transaction. Yet smart acquirers take pains to gain the support of the analyst community when a deal is made public. They know that analysts react more favorably to an announcement of an acquisition if it is followed up with a cogent discussion about the acquirer’s high priority integration initiatives, key risk factors and risk mitigation plans (including the timing of each). Such conversations convey the depth of strategic thought that has gone into the acquisition. It’s not a coincidence that deals that receive positive initial support from the markets tend to be more successful over the long haul than deals for which the market initially reacts negatively.

An integration plan developed prior to signing forces the acquiring company to be honest about the challenges and costs that lie ahead, preparing it for critical Q&A sessions with analysts and investors. Questions that should be anticipated and prepared for include:

• Where will value be created; what are the integration priorities?

• What are the primary risks?

• What are the guiding principles and decision-making processes for the integration?

• How will you know that progress is being made on schedule and that risks are being managed?

• How will you avoid disruptive surprises and unforeseen complications?

Often companies fail to secure the cooperation of the reigning leaders of the target. Yet these leaders will be instrumental in preparing for the announcement and motivating stakeholders. They should be involved in forming and implementing the master integration plan and identifying risk mitigation plans. And for their assistance, the target’s leaders must be fairly compensated so that their interests become aligned with the acquirer’s.

“Analysts react more favorably to an announcement of an acquisition if it is followed up with a cogent discussion about the acquirer’s high priority integration initiatives, key risk factors and risk mitigation plans (including the timing of each).”

A final thought

In this age of increased scrutiny and concern about the trustworthiness of financial statements, and given the lengths to which some executives and companies have gone to mislead their investors, it is prudent to obtaining the services of professionals who know the industry. The more complex the world in which we all do business, the greater the importance of understanding the game and coming prepared to play. An acquirer that employs the right mix of professionals prior to signing a MOU will obtain a more thorough assessment of its financial, operational, management and legal risks. In the end, the ace up your sleeve should be the knowledge you gain from a best practice due diligence process.

Note

1. The analysis was based on information in two databases. The first database contains information from the Securities Data Corporation, which tracked more than 135,000 mergers and acquisitions from 1990 to 1999. From this, we selected only those publicly traded companies with a transaction value greater than US$500 million in which the acquirer held at least a 51 percent interest at the close of the deal. We focused on 1,345 mergers and acquisitions by 945 acquiring companies.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter