Publications Successful Post-Merger Integration: Realizing The Synergies

- Publications

Successful Post-Merger Integration: Realizing The Synergies

- Bea

SHARE:

By Nils Bohlin, Eliot Daley, Sue Thomson – Arthur D. Little

Merger and acquisition activity has grown sharply in the last five years. Since 1992, annual expenditure on such activity has leaped from under $400 billion to over $1,200 billion, and there are no signs of a slowdown. The size of the deals has also grown, culminating in WorldCom’s recent, record-breaking offer of $3 7 billion for MCI.

Why the enthusiasm for mergers and acquisitions? Surveys of senior executives have found a fairly consistent set of motivations:

- To create and exploit synergies (the primary motivation)

- To increase market share

- To protect markets by weakening or eliminating rivals

- To acquire products and/or technologies

- To strengthen the core business by expanding in areas of greatest competence

- To gain footholds in other countries or continents

- To achieve critical mass or competitive size

Unfortunately, a great majority of mergers and acquisitions fail to achieve their hoped-for benefits. Some estimates put the success rate at less than 20 percent. While commentators argue at length about the definition of success and the timescale over which it should be measured, the bottom line remains indisputable; far too few mergers and acquisitions deliver the sought-after profitability, market share, and increased company momentum in a sustainable, long-term way. On the other hand, there are also some notable success stories, such as ABB, Chemical/Manufacturer’s Hanover, Bank of America/Schwab, and GE Capital. So the question is, why do mergers and acquisitions work for some and not for others?

The answers are of course complex. Mergers and acquisitions vary widely along a number of dimensions: company size and diversity; industry characteristics; overlap of products, markets, and customers; prior mergers- and-acquisitions experience of the parties; whether the takeover was hostile or friendly; relative performance strength of the acquired firm; and how much assimilation is desired or required.

Despite this variety and complexity, our experience as long-time observers of mergers and acquisitions – and as active participants in them and counselors to them – suggests that those that fail share one critical blind spot: they treat „synergy creation and exploitation“ as a euphemism for cost-cutting. By focusing too exclusively on costs, they minimize – or defer until too late – the human and cultural dimensions of blending two entities into one seamless, growth-oriented business.

After all, organizations are basically collections of people sharing a common purpose, one or more locations, and other resources such as money, equipment, and common processes. Still, many business managers persist in believing that the latter assets are the „real“ organization, while the people are only the „soft side“ of the equation. But how „soft“ are the people issues if they can bring an otherwise „perfect“ merger-integration effort to its knees – as evidenced in recent press coverage of major transatlantic mergers in the pharmaceutical industry. A recent Forbes 500 study asked CEOs why merger synergies are not achieved: first in their list of „failure factors“ was „incompatible cultures,“ and three of the top six factors were culture-related.

In this article we examine the human and cultural aspect of the merger experience and suggest a process and key principles with which companies involved in mergers or acquisitions can greatly increase the odds of creating an organization capable of synergistic growth.

The Challenge

Clearly, an urgent need to rationalize, streamline, and eliminate duplication will drive the first weeks and months of post-merger integration. However, rationalization increases only the potential of the new company to yield greater value to its shareholders. It is one thing to design a new architecture and relationships on paper, quite another to bring them to life. No matter how visionary the leader or competent the financier, each quickly learns that synergy cannot be generated solely from above – or realized simply by reducing headcount. Synergy requires the engagement and commitment of the whole organization. And therein lies the challenge.

Most mergers are seen as times of chaos, fear, uncertainty, distraction, limitation, and dehumanization. The process is painful, and the results costly. When knowledge capital is lost through turnover of key individuals during a merger, when pride in the company and pride in one’s work are eroded through ill treatment at the hands of merger managers, when innovations are abandoned in favor of outdated practices just because onegroup is considered the „home team“ and the new one deemed expendable, the webs that make the organization work break down and fall apart. When people stop caring, they lose interest in making business processes better. If they are not asked for their opinions, they have no means or motivation to tell the new system designers the hidden secrets of success and sup-portability. When selection processes do not seem fair and open, good people do not step forward – they walk away to take on new challenges elsewhere. These are not the conditions under which synergistic growth is likely.

Fortunately, it doesn’t have to be this way. Managed in a holistic way, a merger can become an opportunity for people to learn, grow, and have a voice. Shared visioning activities and cross-company merger project teams can provide opportunities to meet new people and gain new perspectives and skills. Work-redesign processes give functional team members the chance to innovate, to show what they are capable of. And changes in organizational design or expansions in job scope offer many the challenge of taking on a new job, function, or level of responsibility – even, perhaps, moving closer to fulfilling some of their own, long-held aspirations for their work and their lives.

In many of the mergers we’ve helped with, in industries such as chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and energy, we’ve found that a few years after the merger, people have fully embraced the opportunities created by the merger, and they’ve been able to see that the „old way“ was not necessarily the „best way.“ But two years is a long time in business. The challenge is to shorten this transition period. We believe the approach we advocate here will help to do that.

The problem is that merger managers must juggle strategy, organization, staffing, systems, and culture, on top of keeping the day-to-day business performing. They feel pressure most urgently to demonstrate the wisdom and value of the investment decision by recovering the costs of the merger and boosting short- and intermediate-term share price performance. So they focus on restructuring to realize the benefits of creating economies of scale, streamlining operations, capitalizing on product and market synergies, and spinning off noncore businesses. Meanwhile, they are looking for the next merger or acquisition opportunity. This doesn’t leave them much time or energy for ensuring a synergistic and sustainable foundation of people and operations to support future growth.

Yet building a foundation for continued growth is the key to sustainable success, because it determines how the work of creating the new organization will be carried out. Unfortunately, most post-merger implementation plans seem to assume that if the merger’s financial priorities are thoroughly addressed the human foundation will take care of itself. And, in case after case, this element is the Achilles’ heel of the implementation effort.

The synergy created by a successful merger is a dynamic energy. It arises from ongoing encounters between people and groups with different world views, knowledge, and experience, and it transforms the whole into something greater than the sum of its parts. But it never happens automatically. To harness the valuable differences between two merging companies and convert them into opportunities for innovation, performance excellence, and market leadership, the merging companies need to take a very careful look at the entire merger process.

The Merger Process

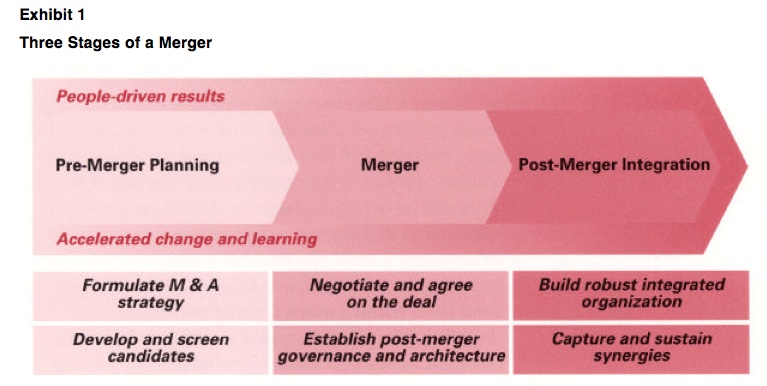

The process of bringing two companies together follows six generic phases that can be grouped into three stages: pre-merger planning, merger, and post-merger integration (Exhibit 1). Harvesting synergistic potential requires leadership capable of galvanizing the organization’s capacity for innovation, change, and growth. It also requires pre-merger and post-merger implementation processes that are tuned to the human and cultural dimensions of the new organization.

Pre-Merger Planning. Concrete and practical methodologies can be woven into the entire merger process to achieve the results everyone wants. Starting in the pre-merger planning phase, visioning and scenario planning will give both decision-making teams a clearer picture of the synergies they can expect and what will be required to achieve them (beyond the mechanics). For example, when a large firm is thinking of acquiring a small and innovative start-up, it is often tempting for both parties to believe during negotiations that „nothing much is going to change – we don’t want to ruin what makes you unique.“ Yet this assertion hardly ever turns out to be true. By playing out various business and organizational scenarios, and envisioning how they can (or must) be handled, the merging companies can set more realistic expectations and prevent key contributors from feeling that they have been „lied to.“

The Merger. An emerging practice among many of our clients is to include a „cultural due diligence“ as part of the overall due-diligence process. While it is not always practical to do this, we have found it very valuable, specifically for clients in the health care and automotive industries. Before and after issuing the Letter of Intent, and certainly before the deal is closed, due-diligence activities can and should include assessments of the historical and present labor/management culture and of critical human resource policies and procedures making up what employees view as core cultural elements. If exempt employees are suddenly going to be asked to complete timesheets, for instance, or all employees will cease to receive a Christmas goose, or if all employees in both firms suddenly have to reapply for their jobs (an approach adopted during the Glaxo-Wellcome merger), or the company’s annual meeting will no longer include spouses and children, these „losses“ will be seen negatively. (One company we know of still hears laments about the loss of Thanksgiving turkeys and hunting rights on company land – more than six years after the merge!)

To identify areas of similarity and dissonance between the two cultures, it is important to take account of results from previous employee surveys, interviews, or focus groups. It may even be worth undertaking new research activities (e.g., Arthur D. Little’s Unwritten Rules of the Game analysis) just for this purpose. Such assessments will point to priorities and help management gauge the extent of needed changes. They may even, in a few cases, reveal potential after-merger costs that are significant enough to jeopardize the viability of the deal.

Post-Merger Integration. To capitalize on the latent synergies of the newly merged or „transition“ organization, the transition process itself must reflect the principles of – and provide the conditions for – synergy throughout its design and execution. This means promptly involving people from both organizations in core business tasks (selling, planning, decision-making), as well as on merger project teams. It also means visibly demonstrating a commitment to learning and to creating together something greater than either party could create on its own.

There are many ways to implement integration rather than just preaching it. You must send senior-level leaders out to talk with employees (not simply to make prepared presentations); encourage cross-organizational reflections at the end of partnering experiments (to capture and pass on lessons learned); and establish „one- company“ measurement processes to minimize the natural tendency to compare one group’s results to the others’. (Do not forget that, to operate this way, the merger’s decision-makers and planners may need to change their own thinking.) To carry off this approach, however, the integration must be:

- • Driven by a crystal-clear vision of the new organization, including its intended mission (core purpose), strategy, and essential values

- Owned and executed by and with key stakeholders

- Fluidly coordinated and flexibly self-adjusting

- Continually providing communication laterally, as well as vertically, across the system and in sync with the needs of ongoing day-to-day operations

- Open, interactive, and responsive to feedback

- Cognizant of human needs for inclusion, order, self-control, and choice

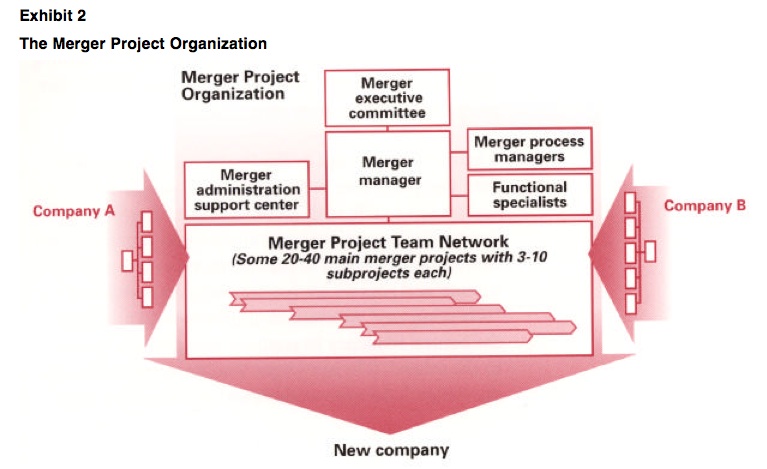

In addition, the merging companies need to form a dedicated merger project organization, which should be networked together to create an integrated learning system (Exhibit 2). Specifically, the Merger Executive Committee is the driving force behind the transition to the new entity. Members of this group must make a commitment to work together to ensure the success of the new system. From the beginning, the way the team members are selected and the way they act, individually and collectively, will be the two strongest messages the new organization receives about what is to be expected and valued.

The Merger Executive Committee establishes the initial guiding ideas and performance parameters for the transition and for the new organization, develops and/or approves strategy, and establishes and oversees the infrastructure for change. The Merger Manager has overall operational responsibility for reviewing and managing time schedules, defining and initiating merger projects, monitoring the implementation of planned activities, and handling merger-related issues as they arise. The detail work is carried out by a network of merger project teams, typically of four types: business segment teams, key process teams, support services teams, and transition management teams. They, in turn, are supported by a fall-time cadre of Merger Process Managers – that is, fast-track managers selected for this assignment on the basis of their capability, credibility, and interest. Members of this cadre facilitate and coordinate progress within and across merger projects, support merger project leaders in integrating their activities with others, and provide coaching and guidance on the tools and methods required for success. Leaders from various functional specialties provide functional expertise and guidance to each of the preceding players as needed throughout the transition. Through mutual support, shared learning, feedback, and coaching, all these individuals become increasingly adept over time at leading the organization through repeated and ever-more-successful mergers and acquisitions.

Once the merged company has established a networked structure of project teams, focus groups, advisory councils, and transition teams, it can help make interdependencies apparent by linking the groups together through learning exchanges, shared after-action reviews, and other processes. Training and coaching in systems thinking, productive conversation, role negotiation, vision deployment, personal mastery, and team learning will help the elements of the merged organization build on one another’s efforts. This kind of skills training can help teams coordinate and integrate projects, while balancing competing interests and objectives. The teams can fill in gaps in technical and analytic tools and methods for each other, and thus be able to capitalize on emerging synergy opportunities and avoid inefficiencies from „not invented here“ and „reinventing the wheel“ syndromes. They will know how and when to provide an outlet for concerns – before such concerns build into problems or crises. Largely by keeping their communications aligned, the teams will maintain commonality of purpose and – through their heightened ability to identify trends and patterns – uncover critical organizational gaps and organization learning needs.

Finally, measurement and communication of the merger’s implementation and its milestone successes are also crucial to the long-term sustainability of enhanced performance and growth. By keeping current results visible, employees can gauge the effectiveness of their collective efforts and see for themselves the value of their combined capabilities. Many of our clients are adopting scorecard systems, which incorporate in some cases more than 100 measures, to track the progress of the merger against set objectives. These scorecards can also beincorporated in the normal planning and control processes of the company. Interestingly, we find that companies benefit almost as much from the greater shared understanding of the objectives they achieve using scorecards as from monitoring closely the progress they are making.

Qualitative measures of progress have to be demonstrable, even if they cannot be measured numerically. An example of such a goal might be: „By the end of 1999, ‘we’ in common parlance (e.g., as heard in the company cafeteria) will clearly mean the merged organization.“ Or „By September, our salesforce will be comfortable representing the products of both companies.“ One important measure easily sensed through employee surveys or casual conversation is whether people believe there was a clear „winner“ and „loser“ in the merger process.

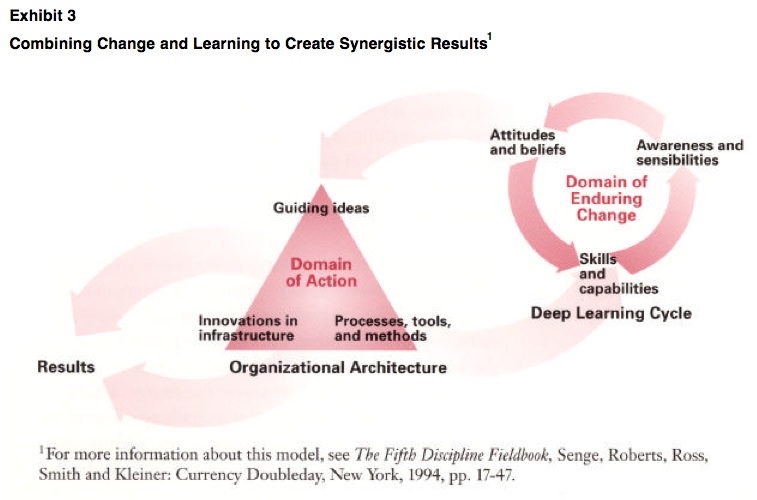

Redesigned business processes, repositioned strategies, and rearranged reporting structures – while essential to the post-merger process – are not enough on their own to ensure that synergy will occur between two entities. These elements make up only part of the components shown at the bottom of the Organizational Architecture triangle in Exhibit 3. Additional tools and methods must be employed, and training or coaching may be needed in areas such as team learning, systems thinking, development of a shared vision, and the deciphering and creation of mental models. New infra-structural elements may also be required. Some will be as basic as job descriptions; others will be much more sophisticated, involving power negotiations up, down, and across the company. All are potentially essential, however, to facilitate sharing of resources, assumption of responsibility, experimentation, and continuous learning from success and failure.

And lying behind this architectural domain, often out of sight, is the domain of deeper learning. This arena offers the greatest potential leverage for synergy and sustainability. Post-merger transition processes must be designed and executed with an eye to how they play into people’s existing attitudes and beliefs; how those belief systems may need to be shifted – often via skill development and exposure to new ways of doing things; and how those expanding capabilities can open up new possibilities, for both the individual and the organization.

The Integrated Organization

In our experience, the employees of organizations whose post-merger integrations have been successful over the long term identify with the new organization and its purpose and potential. They feel responsible for making the new organization a success, and they can inspire others to work with them to bring the organization’s potential into being. At every level in these successful mergers, there are people who are willing to let go of their own limiting beliefs to grow, learn, and improve – who understand their own impact, and work to use it more effectively.Like any organization, a merged one needs knowledgeable people. However, more than participants in any other type of business change, these people also need to be interested in other ways of seeing and explaining the world around them. They must be open to innovative ideas and solutions, whatever the source. Having the skills to analyze problems and challenges and identify best practices, without looking to place blame, is crucial to achieving rapid progress through a wider community of committed people. The more people you have who can understand complex and dynamic root causes while seeing the bigger picture, who want to understand what works and what doesn’t – and why – and who can be effective team players, coaches, coordinators, and/or communicators, the greater the speed with which you can build ownership and sustainability.

Ironically, a post-merger integration situation can be the perfect opportunity to develop these capabilities in existing staff. We have known many people, from unionized workers to senior executives, who, when they were treated fairly and with respect, have designed themselves out of jobs for the good of their firms. By empowering employees as decision-makers during the merger, management can ensure that the merger has powerful, participating contributors. By focusing on aligning performance management, incentives, and other systems with the organization’s carefully constructed vision and core values, the merger team can create a path of least resistance toward the desired results.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter