Publications Who Should Manage The M&A Process?

- Publications

Who Should Manage The M&A Process?

- Bea

SHARE:

2005 M&A Panel Discussion

Our panelists engage in an informative discussion of individual company approaches to managing the M&A process and share their experiences on what has been most successful. We look specifically at the pros and cons of centralized versus decentralized approaches and also examine the role of outside advisors.

With a highly centralized structure or approach, the M&A unit may not involve the business unit heads until a later stage in the process, if at all.

JOHN NIGH (Managing Principal at Towers Perrin): This morning we are privileged to have a very experienced group of M&A practitioners participate in our panel discussion on “Who Should Manage the M&A Process.” I know you will find the speakers’ perspectives interesting and enlightening.

As background for today’s discussion, I’d like to review the results from a recent CFO survey conducted by Tillinghast on the topic of M&A. The responses that we received to the question: “What approach does your company take to M&A transactions?” indicated that the current approach favored a mostly centralized structure, whereas the desired approach showed a balance between a centralized and decentralized approach. For both the current and desired approach, a completely decentralized structure was the least favored.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: John, can you explain what “centralized” means?

JOHN NIGH: I’d like to use the MetLife approach as an example. MetLife has a centralized M&A division with responsibility for taking a disciplined approach to evaluating transactions, either to buy or sell. It’s this division’s responsibility to reach out to the business heads who would be affected by a deal (especially a buy), to make sure that those business heads are part of the process. The structure is mostly centralized such that one department has the standing responsibility to consider and execute transactions. With a highly centralized structure or approach, the M&A unit may not involve the business unit heads until a later stage in the process, if at all. Unfortunately, the highly centralized approach risks disaffecting the business unit heads and may impede implementation but, operationally, it is the least disruptive to the business units.

In a decentralized approach, business unit heads generally take the lead on transactions. For example, if an acquisition of an asset accumulation book or line of business was under consideration by Company ABC, the ABC asset accumulation business unit head would lead the effort. Depending on the company’s standard approach or available resources, the business unit head would then involve either internal or external advisors in the process. These are just two illustrations of the difference between centralized and decentralized approaches, and I know that our panelists will provide us with others.

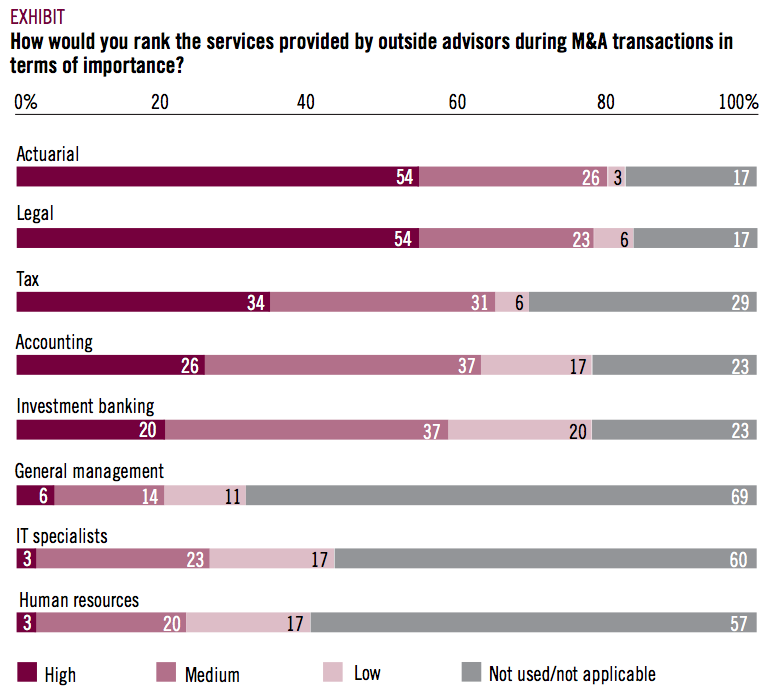

Turning back to the CFO survey results, I would like to discuss how CFOs viewed the importance of various advisory services when asked “How would you rank the services provided by outside advisors during M&A transactions in terms of importance?” These findings (see exhibit, next page) provide a good indication of who is likely to be part of the deal team. The obvious candidates are all here and, in order of perceived importance, they are actuarial, legal, accounting, tax, investment banking, management, human resources and information technology (IT).

Based on my own M&A experience, I would say that both the human resource and IT advisory services are more important than might be indicated by the survey findings. In one of our previous sessions, Joe Dunn (VP and Senior Actuary Mergers and Acquisitions at MetLife) talked about some of the staffing issues that can arise. For example, how do you deal with staff reductions, how do you manage benefit transitions and others? How do you manage those types of issues if you don’t involve the human resource experts early in the M&A process?

With respect to IT, I think that they are, in reality, more important than indicated, especially when you consider the expense synergies buyers have been able to extract by going to a common IT platform.

So, with that as background, I’m going to ask our panelists to share some of their experiences on the most effective and efficient ways to manage the M&A process.

The question of who should manage the M&A process would clearly depend upon the size of the organization and the skill sets it has.

JAMES SLATTERY (Senior Vice President at Allegheny Corporation): The question of who should manage the M&A process would clearly depend upon the size of the organization and the skill sets it has. There have been two times when a large organization I’ve worked for has had the M&A process managed by the strategic planning area, rather than the M&A department.

The strategic planning unit’s responsibility was to work with the various business lines and develop a strategic plan for both organic and acquired growth that would allow us to hit certain targets over some time horizon. Management obviously would have a clearer perspective of what it could attain in achieving some of those targets, and wherever an acquisition would support hitting those targets, the acquisition option became a component of the overall business plan. The management of the process or, more specifically, the management of coordinating the business objectives with an acquisition objective, was coordinated by the strategic planning unit. This was a very centralized approach.

Now, depending on what the steps to a particular acquisition may be, the implementation of the deal might be somewhat more decentralized. For example, if the planned expansion ultimately incorporated an integration of a target within an existing business unit, then clearly that business unit would have to be very actively involved. The involvement would range from formulating the business plan and monitoring the due diligence process to ensuring that there is a good coordination and a good symmetry with the existing personnel and business, so that stated cost savings, for example, can be achieved. If it were an acquisition that would add a new line of business, it might be managed by the executive in charge of the particular business unit most affected by the transaction. That manager would, in turn, call on the various services departments to ensure that the new business unit would ultimately fit into not only the organizational structure, but also into the employee structure.

We have advisors who know what our objectives are and what needs to be done. There’s a high degree of interaction between the internal staff and the outside advisors.

SCOTT WILKOMM (President of Scottish Re Group): There are two axes that one can look at in terms of how our company has managed transactions. One is chronological. As our organization has grown, the level of involvement of different parts of the organization has changed accordingly.

The other axis is somewhat reflective of the size of the transaction and its impact on the organization, whether financial or strategic.

So our approach to the M&A process has evolved in many respects. In the early days, the senior management team was where it got done because that was the universe of capable folks within our organization who could lead a transaction. Today it’s a little bit different, as it depends on the nature of the transaction and its size. For example, we have individuals who are dedicated to portfolio transactions, something we didn’t have two years ago. So now we have a designated resource that solely focuses on those types of transactions, and those individuals will draw from other resources in the company such as legal, tax resources or from elsewhere in the actuarial team.

The other aspect is that in many transactions we have worked with investment bankers. There’s a broad continuum of what you get when you employ an investment banking firm to work with you on an acquisition. We have developed a working relationship with three specific individuals from three different firms who understand our organization and its objectives. They know our “hot buttons.” In many respects, they know where we would say yes and where we would say no. They know how we like to approach valuation and the other important metrics and variables that go into a transaction. They know what those metrics and variables are for our organization.

More broadly speaking, we work with individuals as opposed to firms, to help leverage our internal team, which might not be as robust as at some other larger organizations. For example, on the legal side, we have an in-house team that’s quite capable, but we also rely on our outside counsel to provide advice on tax, corporate governance, securities law and transactions. So we have advisors who know what our objectives are and what needs to get done. There’s a high degree of interaction between the internal staff and the outside advisors. Also, since the relationship is with the individual and not the firm, if that individual leaves, we would likely follow him or her to the new firm.

As our organization has grown, it’s no longer possible for everyone in senior management to touch every transaction. Our approach now, depending upon the transaction, of course, is to designate one member of the senior management team to lead a given transaction. That person then draws upon the resources of the organization, as well as external advisors, as necessary. So that’s how we go about the M&A process at Scottish Re.

JOHN NIGH: So would you characterize that as a decentralized approach?

SCOTT WILKOMM: Well, I can see from your initial definition or example why you might think this. I actually believe it’s pretty centralized. The leadership on most transactions will emanate from our group leadership team, which includes 10 people. In all cases, however, our general counsel, CFO and group chief actuary tend to put their handprints on all transactions, regardless of size, with the possible exception of very small portfolio transactions.

AUDIENCE QUESTION: Isn’t there a built-in conflict of interest in the centralized approach, where management’s incentive compensation is based on doing so many transactions, that might lead to aggressive pricing or noncomplementary transactions?

JAMES SLATTERY: Possibly, if not appropriately managed. An M&A department could influence the potential success or failure of any acquisition or any merger so it can meet its departmental goals and objectives. So it is very important that those goals are closely aligned with those of both the business unit and the company.

As our organization has grown, it’s no longer possible for everyone to touch every transaction.

PETER GENTILE (Senior Consultant at Towers Perrin): The examples that I’m going to go through may offer some insights. I have one on the buy side and one on the sell side. When John and I talked about the topic, I viewed it a little differently, as to whether or not the process should be driven externally or internally. In my experience, I have two situations where the process was very much driven internally and it went very much astray. This demonstrates that while I may not know exactly how a transaction should be managed, I do know how it can be mismanaged.

So let me set up the first example, and it’s from the buy side. You’ll need a little background to know precisely how something could go this wrong. This transaction is all public, although it’s a little sensitive, so I will avoid mentioning company names.

I worked for a company that was really focused on growth during the worst possible time in the insurance market — a soft cycle. The reason for this really had to do with individuals. The company was run by a very strong personality who was head of the biggest division within this European conglomerate. This person had set his sights on running the entire group. Again, he was a strong personality and he had bet an awful lot on global expansion. The company announced that it would become a global organization and made a significant U.S. investment in 1997. He wanted that investment to succeed, and there was no question that he would do virtually anything in his power to succeed.

We had brought on a new head for the U.S. subsidiary, a person who had not run a company before, but a person who had good intentions and who was very competent. It was obvious that organic growth was just not going to satisfy the objective of the chairman in Europe. This company was growing organically, and it was growing quickly, but not quickly enough.

So the company looked toward making a major acquisition on the order of magnitude of a number 8 buying a number 12 to become number 4. The first step was to put a team together, and as part of that first step management hired an investment banker, which was one of the things that was done correctly, in my opinion. The investment banker put forth a list of targets and, for an acquisition of this size, there were only about 15 possible candidates. Of those, probably five, six or seven were just too big. So the ultimate list was whittled down to five, and then, based on some personal objectives, down to one. While the right reasons were all considered — market presence, reputation, etc. — the driving force was a personal agenda.

We then went through the due diligence process. The due diligence team was set up in the following way. The members of the team all reported ultimately to the head of the U.S. operations, which made some sense. They certainly should have been on the team. But they reported to this fellow not only as a part of the due diligence team, but also in their normal day-to-day business life. And then, of course, the U.S. head reported directly to this very, very strong personality in Europe.

So what went on during the due diligence process? Well, the first thing is that the actuaries did their job and reported that the company was significantly under-reserved. That news was passed up to the chairman, who heard it and then went directly on to the next matter rather than really focusing on the incredible news that he had just received. Ultimately, the winning bid — ours — was materially higher than the next bid. The bad news did not deter the strong-willed boss in the process. He wanted to go full speed ahead, and so we completed a very expensive transaction. Predictably, the U.S. company went into runoff over roughly a three-year time frame. This transaction also contributed significantly to the trials, tribulations and the problems of this once very big insurance conglomerate in Europe.

I think we can all visualize what went wrong with what I just described. I have a suggestion as to how to avoid this situation. At the very least, the incentives, motivations and objectives of the people running the process must be aligned not only with senior management’s goals, but with the goals of the owners of the entity. In this case, the owners were represented by the board of management. I feel very strongly that if a subcommittee of that board had been more involved in the process and if the due diligence team had reported directly to this group, we could have avoided making an investment that cost the company several hundred million dollars.

At the very least, the incentives, motivations and objectives of the people running the process must be aligned not only with senior management’s goals, but with the goals of the owners of the entity.

JOHN NIGH: So they ignored the advice of the actuaries?

PETER GENTILE: Yes. Let me say it a different way. Of course, you’ve said it the appropriate way, the direct way. A different way to say it is that the goals of growth, at any cost, superseded the actuarial findings. These findings indicated that, in addition to the purchase price, another several hundred million dollars needed to be put into the company. This is a pretty severe example of a process that went awry because of personal goals and motivations. Unfortunately, this probably happens more than anyone really wants to admit. The result is not always as serious as this. You might have the other situation where someone always says no to avoid the possibility of failure. But the financial implication may be the same because a real opportunity is missed.

My second example is on the sell side. It was not quite as serious, but a fairly significant mistake was made that largely mirrors my buy-side example. We had the opportunity to sell a division whose value was very much tied to the individuals who were running the company. Like many businesses, the more significant assets went up and down the elevator and in and out of the office every day. The parent company was in some financial difficulty, and the goals and motivation of the board were a little different from those of the business unit. The board just viewed the opportunity to divest as an opportunity to make money. The problem wasn’t the goal, however; one simply needs to understand exactly what one is selling. In this case, the decision makers neglected the people assets.

The board was focused on squeezing as much value out of the company as possible, without a lot of thought as to how that value was created. We went through a six-month process where we focused 100% on selling the corporate entity.

While there should have been a couple of options open to us, including selling the entity or proceeding with a renewal rights transaction, the board did not consider the latter. Getting someone to buy the legacy liabilities and buy the balance sheet was something that just was not going to happen, whereas doing a renewal rights deal was a real possibility. We had very capable bankers involved who tried their best to convince the board that an outright sale was not the right deal to do.

The difference in who the decision makers were in this example is why I consider this a mirror image of the first example. In the first situation, the process was run by individuals with their own agenda. In the second situation, the process was run by senior members of the board who did not have a realistic view about what was feasible. They were not listening to business unit heads or their bankers.

In the end, they neglected the opportunity to really extract value from an asset that they had built up over a period of several years.

JOHN NIGH: Peter has done a good job of outlining a significant failure and an opportunity squandered. Do any of the panelists want to share any insights on similar experiences that they may have participated in or witnessed?

The board just viewed the opportunity to divest as an opportunity to make money. The problem wasn’t the goal, however; one simply needs to understand what one is selling. In this case, the decision makers neglected the people assets.

SCOTT WILKOMM: Well, I think it’s probably fair to say that we should have some failures, because the lessons learned from failure are some of the most powerful. I can think of one particular failure in a transaction we did three years ago, and it specifically relates to how we evaluated the future liability for postretirement benefits. This was outside of the United States, which added a certain level of complexity.

We had a valuation from a reasonably reputable actuarial and human resource consulting firm, not the sponsor of this seminar. There was a determination that this particular plan was underfunded to the tune of roughly a million pounds. We agreed with the seller that it would be on the hook for any deficiency up to the million pounds. Under this arrangement, if it went down a little bit during the course of time, they would still be in good shape. If it went beyond the million pounds that our work had suggested, then it would be on our nickel. So making sure that you had great confidence in that number was important.

Unfortunately, the rigor of the actuarial work was somewhat light, in my opinion. We ended up bringing in another firm, after the fact, to look at it again, and this second valuation suggested that it was more like two and a half million pounds. So, long story short, we ended up eating a million and a half pounds because of a poor job done by this particular firm.

How do you know whether you’re getting quality work product? I think we probably erred in placing too much faith in the work that was done by this firm without analyzing its thoroughness. I now make sure that we do our own due diligence on the work of our advisors. In the end, it wasn’t a huge value destroyer, because we made up the value elsewhere, but it was a bit of a pain in the neck to deal with.

JAMES SLATTERY: I’ve been kind of lucky. I haven’t bought a company that went bankrupt, so I’ve had a lot more successful transactions than failures. As I mentioned yesterday, clearly there are surprises in any acquisition. In one instance, we felt that the claim reserving methodology used by the company that we acquired was not the most appropriate, which led to some financial surprises. There is also — and I think Peter touched on this — risk associated with the fact that a due diligence team often is making representations and presentations to another group, and it is this other group that will actually decide on the transaction.

There was an instance when we presented to the CEO while we were still negotiating with the target on acquisition price and acquisition terms. Unfortunately, the CEO was having lunch with the CEO of the selling company, and he proceeded to give away our terms and pay more money than I think we needed to. So I don’t think that this example is necessarily a failure, but I think that it is beneficial to maintain a process that protects the integrity of an acquisition. In this case, we should have waited longer before getting our CEO involved.

I don’t believe in synergies. I think they’re great if you can find them, but you can’t eat synergies at the end of the day. An acquisition requires a lot of financial discipline.

JOHN NIGH: Is there ever an instance where a non-accretive deal should be considered, let alone a dilutive deal?

SCOTT WILKOMM: I don’t believe in dilutive deals. I also don’t believe in deals that don’t add value, so I struggle a little with that concept. And I don’t believe in synergies. I think they’re great if you can find them, but you can’t eat synergies at the end of the day. An acquisition requires a lot of financial discipline.

I actually think purchase accounting is a superior accounting methodology for M&A transactions. When I was a banker, we used to do pooling transactions with banks, where more of them worked out than didn’t, but that had more to do with the environment of the banking industry in the late 1980s through the mid-1990s. I believe, at the end of the day, on a pure economic basis regardless of the accounting — return on weighted average cost of capital needs to be accretive to the acquirer. GAAP is something that tries hard but still doesn’t completely represent the economics of the transaction. Some of that may come from just a difference of opinion on value. It could be a distressed seller; it could be a motivated seller, or it could be true operating efficiencies in the back room of the combined organizations.

Synergies are great, but I just don’t think that they belong in financial models. They’re wonderful, though, if they appear. I think, all in all, if I’m taking a hundred dollars off my balance sheet, I want to earn something on that hundred dollars in excess of the four points I’m earning in bonds today. So I don’t feel there is a basis for dilutive deals. And I know a lot of people will disagree with that.

JOHN NIGH: On the contrary, I think most people would agree with you.

SCOTT WILKOMM: I’ve been in conversations with people where they say, we can tolerate some near-term dilution for the long-term strategic benefit. Rarely ever is near-term dilution near term.

JOHN NIGH: Well, it does sound like there is some consensus here. One that I heard was don’t get the CEO involved too early! The other, which is somewhat related, is don’t give an individual who has a vested interest one way or the other the sole decision-making authority.

It seems to me that, on balance, the panel would favor a more centralized approach. I also heard that a deal may fail if the acquirer doesn’t adhere to a rigorous and disciplined approach to due diligence, which necessarily requires thoroughly incorporating all relevant and material due diligence findings in the pricing of any transaction

Is this a fair summary?

PETER GENTILE: I agree with exactly what you’re saying, and I think the issue with getting the individual departments involved from a strategic point of view is that you do run into people who have agendas that can impact their view of the transaction. However, there are situations where you simply need their expertise, so you need to temper the advice they give with the knowledge that they might have a vested interest in influencing the decision.

With a centralized approach, you have a group of people whose charge, day in and day out, involves managing this plethora of challenges, disciplines and activities.

JOHN NIGH: Think about the complexity of these transactions: We have tax issues, accretion/dilution analysis, the management of many internal and external advisors, management of the C-suite executives, possibly the evaluation of a multitude of product lines, people issues, transition and integration issues, and others.

With a centralized approach, you have a group of people whose charge, day in and day out, involves managing this plethora of challenges, disciplines and activities. In my view, this approach assures more consistency, rigor and discipline than you might get from a decentralized approach, which is being managed by an individual that has another full-time job for the rest of the year. I don’t think there’s one answer, but this view seems to be largely supported by the experiences of these three panelists. And, with that comment, I would like to thank the panelists and our seminar attendees.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter