Publications M&A Due Diligence: The 360-Degree View

- Publications

M&A Due Diligence: The 360-Degree View

- Bea

SHARE:

By John O. Nigh and Marco Boschetti

By taking a complete look at all the relevant sources of value and risk, the chances of a successful acquisition increase significantly.

With the resurgence of merger and acquisition (M&A) activity in the financial institution sector, it’s important for companies seeking to grow by acquisition to make sure they look at the full range of issues in any contemplated transaction. Knowing how to manage the financial, strategic and people challenges that are bound to arise can greatly enhance the chances of a successful deal.

The forces influencing M&A decision making and, in some cases, encouraging deals, have not changed since the late 1990s. They include:

- satisfying customer demands

- new growth opportunities

- deregulation

- shareholder pressure for results

- economies of scale

- critical mass

- access to capital.

The question for senior managers contem- plating an acquisition is whether the current round of M&A activity will leave them feeling more satisfied than their previous experiences. In several surveys of the last decade, senior executives consistently rated their transactions as unequivocally successful less than half the time, making the odds of success worse than a coin toss.

Yet there is now some evidence that man- agers believe recent mergers have been more successful than in the past. This could be directly related to better pricing, as the average premium paid (excess of purchase price over current book value) has dropped to a range of 20% to 35% from 50% or more. The implied risk discount rate has risen from the 10% to 12% range to a level of 15% or higher. The overall trend in transaction pricing has been downward, toward a more balanced value proposition between buyers and sellers. This is in contrast to the transactions of the late 1990s, when pricing was heavily biased in favor of the seller.

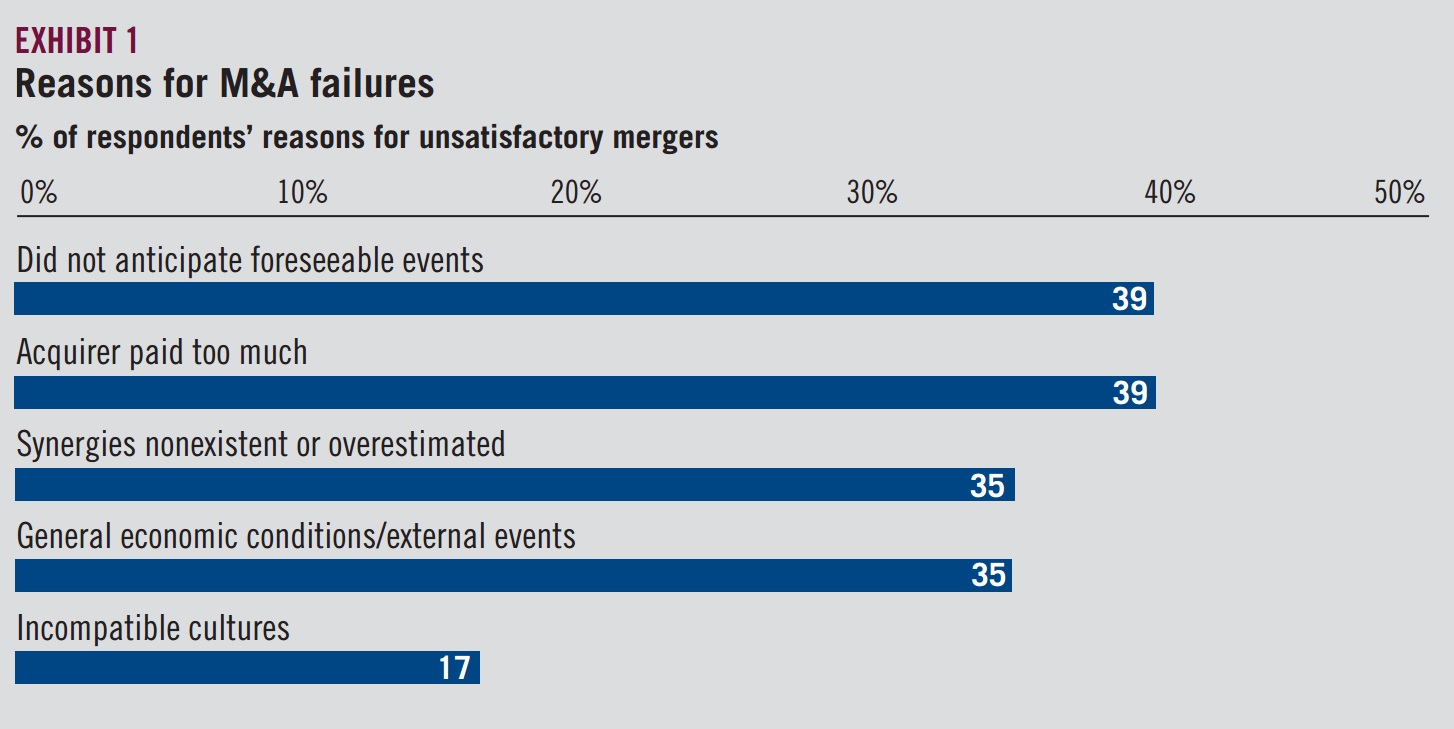

Based on the most recent survey in this area, the leading reasons that so many deals in the past have failed are now widely known (see Exhibit 1):

- not anticipating foreseeable events

- paying too much for the acquisition

- not achieving the synergies anticipated

- general economic conditions or external events.

Interestingly, incompatible cultures, which was one of the leading reasons for merger failure in past surveys, has now been relegated to fifth place in this survey, account- ing for only one out of six responses.

The current reasons for failure do have one thing in common: They could have been avoided by conducting proper due diligence. In fact, the recent drop in the premium paid for an acquisition is most likely due to improved due diligence. This trend can continue if managers practice what we call 360-Degree Due Diligence (360 3D).

DEFINING 360-DEGREE DUE DILIGENCE

The 360 3D process is a comprehensive approach that engages all the relevant disciplines in order to address all the key issues that are embedded in the target to be acquired. These disciplines include actu- arial, legal, tax, accounting, underwriting, claims, investment banking, general man- agement, information technology (IT) and human resources (HR).

The 360 3D process can help assess occa- sionally ignored aspects of the target that may have a significant impact on the value of a deal and might lead to embarrassing situations in the future. Examples are compliance (Sarbanes-Oxley, labor and sales), HR plan transition issues and costs, pension plan funding, and tax and regulatory issues.

With regard to the value that the buyer is contributing to the transaction, the 360 3D process can identify significant finan- cial considerations that can add value that may or may not be included in the price paid by the buyer. These include cost savings from moving to a common reward platform and a common IT platform, synergistic benefits of combining sales forces, tax savings associated with a con- trolled foreign corporation structure and others. At the same time, 360 3D does not ignore the fact that a significant portion of an insurance company’s sale price comes from its existing and new business.

DUE DILIGENCE PROCESS

Fundamentally, due diligence means assessing price and identifying financial risks. Critical questions to be addressed include:

- What is the value of the acquisition target?

- What value will it add to the acquiring company?

- What are the synergies?

- What are the risks that need to be man- aged to gain value while minimizing risk?

- What are the liabilities and costs being acquired?

- What are the off-balance-sheet liabilities?

Risk and value of the target, plus any lia- bilities, are usually viewed as associated with the basic business of the target, accounting for as much as 80% of the value of a target insurance company. They encompass:

- adjusted book value

- value of the existing book of business

- expected value of new business

- risks and liabilities of existing business (hidden or off balance sheet), e.g., adequacy of claim reserves and claim exposures

- risks and liabilities of acquiring an enterprise (usually off balance sheet), such as environmental liabilities, prior assumption reinsurance contracts and market conduct exposures.

But there are also values, risks and liabili- ties associated with the people side of the business that are frequently missed. One important area is pension and other “total rewards” liabilities. This can represent substantial unrecognized or underestimated obligations not immediately apparent to the acquiring company. This is a particular problem if the target operates in countries where local laws and customs regarding pay and benefits differ sharply from those of the home country of the acquiring company. The list of such rewards certainly starts with pensions, but extends to many other “accruing” obligations (e.g., termi- nation indemnities, retiree medical, jubilee payments, accrued unused vacation).

Other areas often needing attention include:

- retention costs for key personnel

- severance costs for “excess” personnel

- fixed-term contracts with key executives that carry future liabilities.

These people-related risks and liabilities can have a substantial effect on the acquisition value — and the price. For example, pension liabilities for all companies in all sectors can be as much as 200% of the value of the company. In the insurance sector, pension liabilities can range up to 50% of the value of the target company.

Discovering these liabilities after the sale is a little like buying a $400,000 house and finding that you have to spend half that amount again to fix the foundation. The 360 3D process means looking at business and people values together with the risks, and then asking:

- What is the value of the book of business and the risk of missing that value?

- Who are the value-creating people and what are their capabilities within the target enterprise?

- What are the unrecognized or underestimated people liabilities?

- What will be the ongoing cash flow and expense implications of integrating reward programs?

- Taken together, what is the “real” value of the business?

- What would a prudent investor be willing to pay for that “real” value?

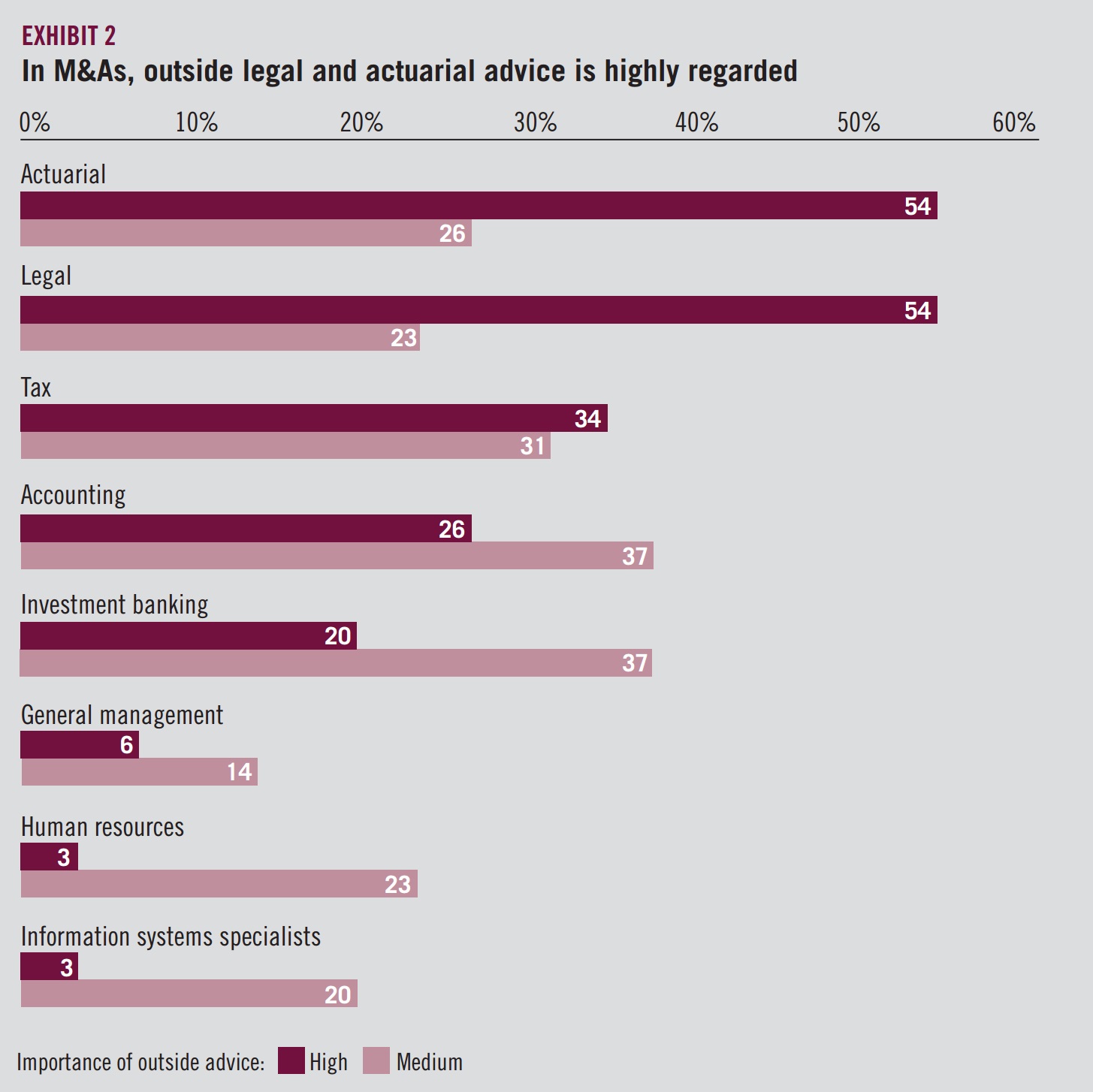

In actual practice, 360 3D means conduct- ing parallel, but interrelated, analytic work streams to arrive at an accurate picture of value and a reasonable price. It consists of the business analysis and the analysis of people-related issues. A practical problem exists with respect to the perceived impor- tance or value contributed by the various advisors to the 360 3D process (see Exhibit 2). Relative contribution or impor- tance can vary in meaningful ways from one M&A transaction to another and it is therefore important that all relevant advisors be involved, not just those with a higher perceived importance.

THE BUSINESS ANALYSIS

The business analysis focuses on rational projections of future earnings. It uses historic data to support future projections but avoids momentum projections — the assumption that the target business will continue to head indefinitely in whatever direction it’s going in now. Business analysis should identify and model synergies between the target and acquiring company, as well as specifically account for risk parameters and risk mitigation strategies. It should also encompass rigorous legal and accounting due diligence.

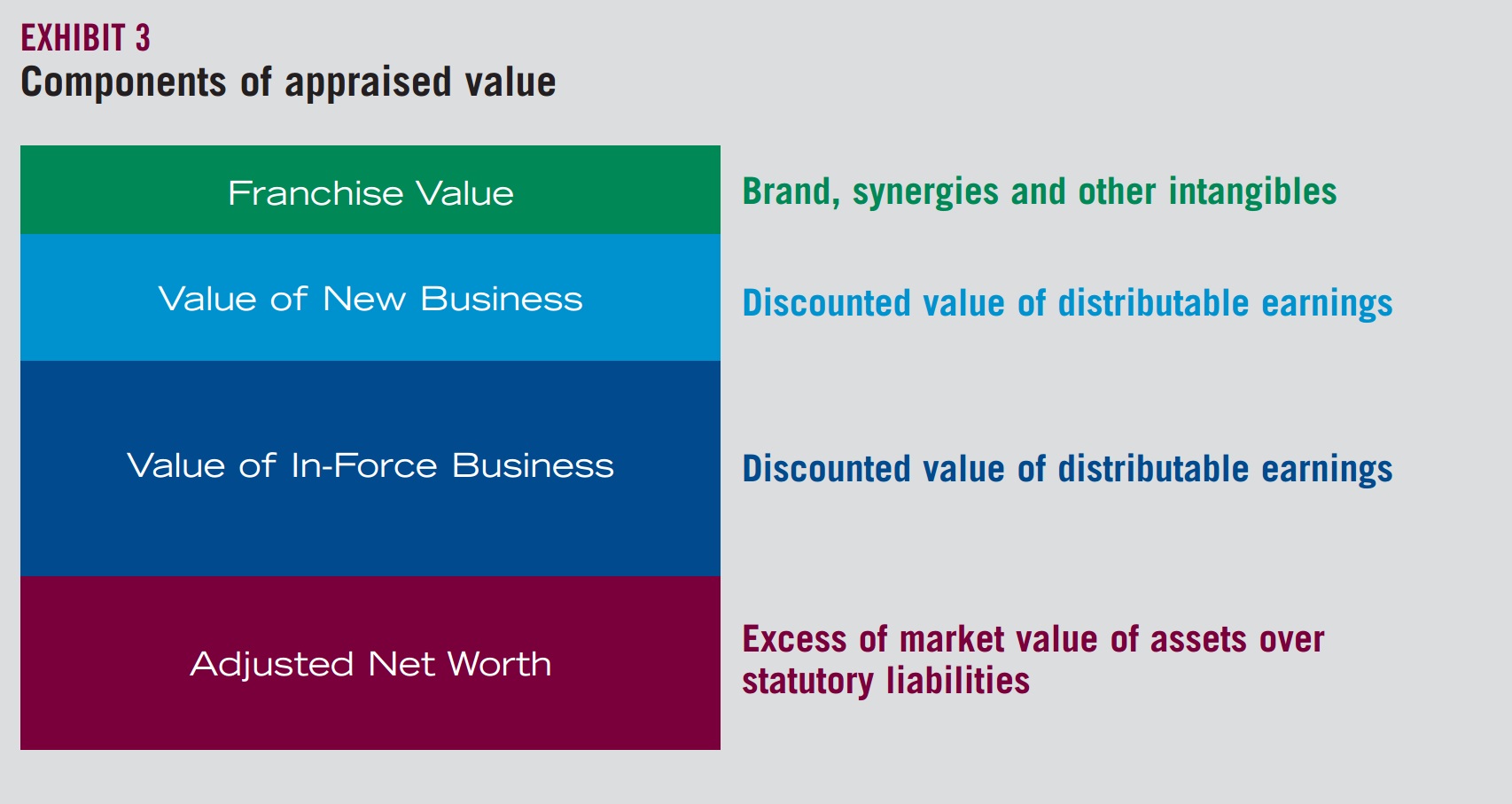

The business analysis produces a financial evaluation detailing four basic components of appraisal value: adjusted net worth, value of in-force business, value of new business and franchise value (see Exhibit 3).

A second product of the business analysis, the strategic evaluation, examines cultural fit issues. Are the cultures compatible and complementary, or will they create funda- mental conflicts about “the way we do things around here”?

The strategic evaluation also looks at the sources of organizational performance and the organizational capabilities that the target offers. Some of these capabilities may over- lap with those of the acquiring company, and some may be so “additive” that they are actually the point of the deal. For some acquirers, for instance, it may be faster and easier to buy a great distribution capability than to build one or renovate one.

Additionally, the strategic analysis examines the target’s market position. Is it robust? Is it sustainable? What is the target’s orga- nizational (e.g., geographic, product and distribution) fit with the acquirer? What are the business risks it brings to the merger?

PEOPLE-RELATED ISSUES

The second major due diligence work stream is the analysis of people-related issues. It looks at both the existing people-related values and liabilities of the target (the “skeletons in the closet”) and the post- merger people-related liabilities and costs, including the cost of aligning the compen- sation programs of both organizations.

The people-related work stream systemati- cally examines a comprehensive set of HR issues. It begins by assessing the value of the people assets being acquired, including a detailed profile of key management at the target and the full range of skills and capabilities held by the target.

The analysis also examines HR issues that can have an adverse impact in key areas.

- Profit margins. Typical problems might be an understatement of existing program costs or commitments to future compensation and benefit programs. However, this also covers fully budgeting for redundancy and retention programs.

- Balance sheet. Considerations include change-in-control triggers, performance compensation contracts and — most especially — postemployment liabilities (e.g., pensions and retiree medical) that may be understated or underestimated.

- Revenue. These issues can range from sales incentive plan designs to the impact from likely turnover.

Organizational Effectiveness

The people-related work stream also con- tains reviews of organizational effective- ness issues. Critical questions on how well the two organizations will fit together include:

- Are the job and role definitions compatible between the two companies?

- Are the reward structures compatible? That can be a particularly material question when the target company’s compensation plan pays significantly less or more than the acquirer’s plan.

Organizational effectiveness evaluation also means assessing the barriers to, as well as the enablers of, streamlining the workforce. These can include legal and political issues as well as procedural requirements. Acquiring companies need to pay special attention to the specific constraints and complexities that can arise when moving into a target company’s territories and markets. Here’s a small sampling of country-specific HR concerns.

- China. The financing practice of benefits varies significantly by company, as does interpretation of the accounting regulations.

- France. The costs of remodeling work- forces can be prohibitive.

- Germany. An acquisition can trigger acquired rights. Other laws restrict asset transfers and permit significant variation in pension valuation methods.

- Japan. The work culture is characterized by complex compensation plans, minimum legal benefit levels, limits on reduction in benefit levels and restrictions on retirement plan changes.

- U.K. Pension plan liabilities are invari- ably large, and a thorough examination is always critical.

The 360 3D process combines the output of these and other work streams and arrives at a comprehensive risk-adjusted price that reflects the full value of the target from a financial, strategic and people standpoint.

A CASE STUDY

In a recent project, a U.S. insurer determined that the present and future book of business of the target company — a European multi-business financial institution — was $5 billion. Taking into account related synergies both expected to derive from the deal, the U.S. company was initially prepared to pay $5.5 billion.

However, a closer look at the people issues revealed that one-off golden parachutes to senior management in the event of a change in control amounted to $100 million. Unbudgeted pension costs, governed in part by local laws, amounted to another $30 million a year for 10 years for a total of $300 million ($220 million on a present- value basis using the buyer’s earned rate). Rationalizing the compensation plans the two companies amounted to a one-time cost of $10 million. And the complex regulations governing workforce stream- lining would have created additional costs of $10 million. Taken together, these people- related costs amounted to $340 million — the amount by which the acquirer would have overpaid in the deal had it not taken the 360-degree approach to due diligence.

THE 360 3D VIEW

If the current round of M&A activity is going to lead to happier conclusions than those of the 80s and 90s, companies need to do more to have a precise understanding of shareholder value. When you are looking at a target company, look around — all the way around. Take the 360 3D view.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter