Publications The Role Of Finance In Successful Serial M&A

- Publications

The Role Of Finance In Successful Serial M&A

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Oksana Kukurudza, Jeff East, Aneel Delawalla and Sara Cima – Accenture

What distinguishes companies that gain maximum competitive advantage from mergers and acquisitions—deal after deal—from those that do not? An Accenture survey of finance and strategy executives from serial acquirers around the world suggests that successful M&A is based on five key practices.

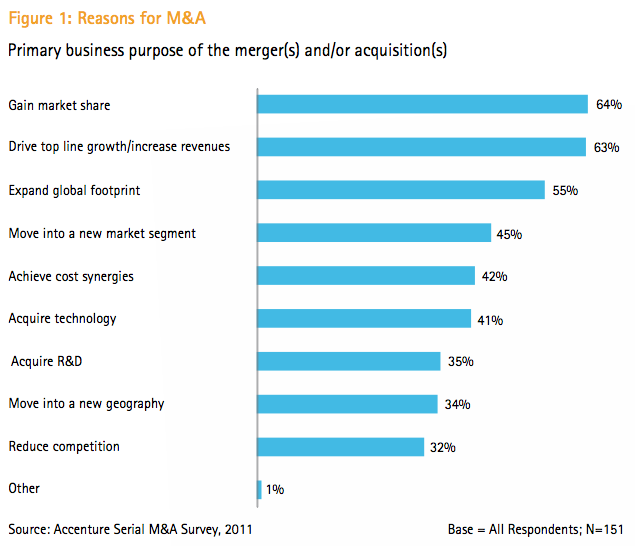

Why do companies decide to intensify their merger and acquisition efforts, and what separates those that generate value from their M&A deals from those that do not? In a 2011 global Accenture survey of finance and strategy executives from serial acquirers around the globe (organizations that have acquired more than two businesses within the past five years), we sought to find answers to these questions. In this study, we also placed particular emphasis on post-merger integration (PMI) for the Finance function. (See “About our research.”) Our respondents’ most commonly cited reasons for M&A were to gain market share and to drive top-line growth. (See Figure 1.) Indeed, when serial M&A succeeds, it becomes a powerful source of competitive advantage. Serial acquirers with strong M&A capabilities outperform their industry peers in terms of overall growth and value generation.

About our research

In 2011, Accenture conducted a survey to explore the aspirations and best practices of companies that engaged in serial M&A activity. Our survey sample comprised 151 finance and strategy executives from 12 countries around the world, representing 21 industries. Forty percent of the respondents were chief financial officers; 25 percent, finance vice presidents or directors (or the equivalent); 25 percent, strategy vice presidents or directors (or equivalents); 11 percent, controllers.

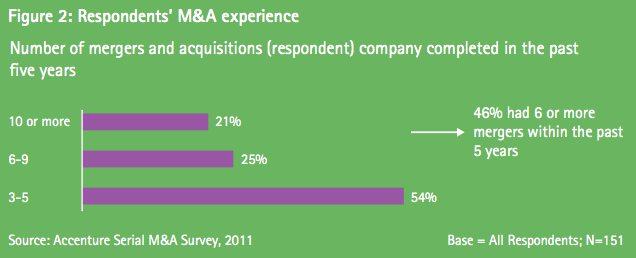

Respondents hailed from companies that recorded between US$500 million and US$50 billion in revenues during their previous fiscal year, with 84 percent having revenues greater than $1 billion. Forty six percent of the survey participants worked in businesses that had completed six or more mergers or acquisitions within the past five years. (See Figure 2.)

In addition to the survey, Accenture conducted in-depth interviews during June 2011 with finance and strategy executives from a number of serial acquirers.

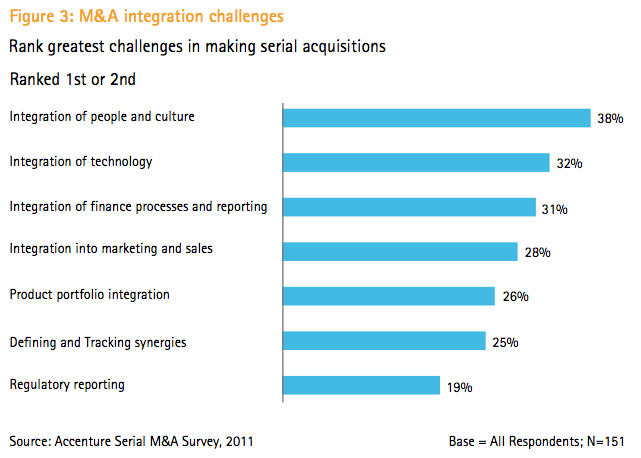

Yet a 2011 study conducted by Accenture revealed that serial acquirers, while strong in M&A governance, strategy management and transaction management capabilities,are challenged by integration management — a core success factor to successful M&A. Moreover, our survey showed that integration of people and culture along with integration of technology and finance processes and reporting, count among serial acquirers’ toughest PMI challenges. (See Figure 3.)

There may be several factors driving the challenges of integration for serial acquirers. For example, with the accelerated globalization of business and emergence of the multi-polar world—in which economic power is shifting toward emerging markets—many M&A deals are taking place across broad geographies with diverse cultures and markedly varied management philosophies. This global reach of M&A adds layers of complexity to post-merger integration planning and execution.

Of course, serial merger and acquisition activity ebbs and flows with economic cycles. At times, the trends run counter to even the best informed expectations. For example, many observers anticipated that M&A would rebound in 2011. With the global economy continuing its cautious recovery, businesses seemed ready to invest their excess cash idled by the downturn into inorganic growth opportunities. Yet M&A volume did not pick up quite as expected.

But regardless of the up-and-down cycles, serial M&A merits study for several reasons. First, serial acquirers drive the market. While they represented just 9 percent of all acquiring companies during 2003-2009, they accounted for about one- third of all deals executed and nearly one- half of total deal volume during that same period, according to a 2011 Accenture study. Serial acquirers also tend to pursue big deals that span several countries, often in emerging markets. Finally, these M&A players face unique challenges. For instance, they take on multiple complex deals simultaneously and can encounter regulatory and cultural barriers while managing cross-border deals.

Five PMI enablers

How can aspiring serial acquirers, or those that have struggled with PMI, avoid costly mistakes and execute M&A deals that deliver the promised competitive advantages?

Our survey of seasoned acquirers reveals five critical integration enablers that can help companies successfully plan and execute their next merger or acquisition:

1. Strong integration governance

Setting the overall direction for the integration of people, corporate cultures, financial processes and technologies upfront and throughout the PMI process.

2. Dedicated team

Establishing an internal team (supplemented if needed by a professional service team) that is charged with orchestrating the PMI effort.

3. Steadfast focus on target realization

Monitoring synergy outcomes and making midcourse corrections as needed to achieve targets.

4. Standardized PMI approach

Using templates and a proven methodology for integrating newly merged or acquired entities.

5. Robust enabling infrastructure

Setting up global operations, processes and systems to support effective and efficient PMI.

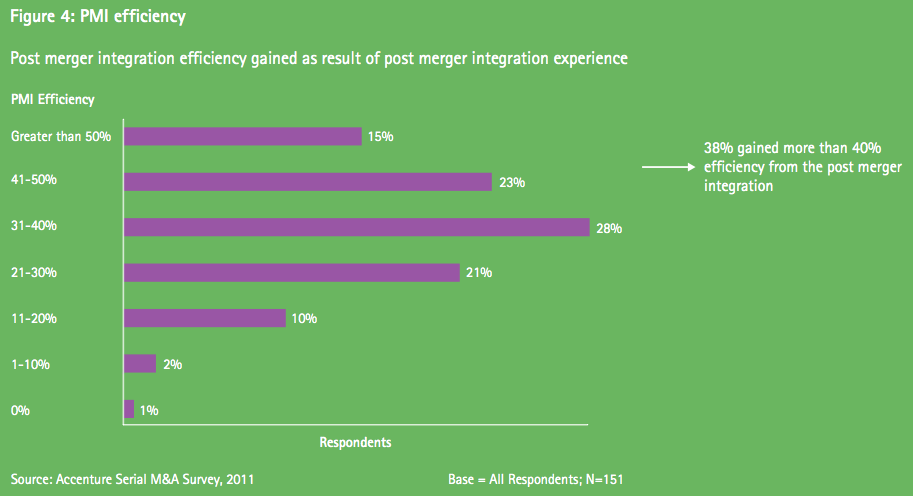

By exploiting these enablers, companies position themselves to ride waves of M&A opportunities as they arise around the globe and to capture the synergies and other advantages these opportunities present. In our survey, almost all (87 percent) of the respondents gained more than 20 percent PMI efficiency over the past five years. More than one third (38 percent) gained more than 40 percent PMI efficiency in that same timeframe. (See Figure 4.) Our findings suggest that these winning firms were more likely to have applied the five enablers we identified.

But the enablers are not just about generating measurable top-and bottom-line business results. They also help companies avoid the pitfalls inherent in struggling with M&A deals on a case-by-case basis. By mastering the enablers identified in our study, companies establish a consistent, comprehensive and reusable approach for managing upcoming mergers and acquisitions.

The finance function’s critical role

The enablers deliver even greater strength when they are orchestrated by the acquiring company’s finance function. Indeed, when M&A activity intensifies, chief financial officers (CFOs) are well positioned to lead and extract maximum business value from merger integration efforts on behalf of their enterprise. While much of M&A activity is focused on driving growth, CFOs who can also realize targeted synergies and cost efficiencies can powerfully differentiate their company’s position in the market for all key constituents—including shareholders, customers and employees.

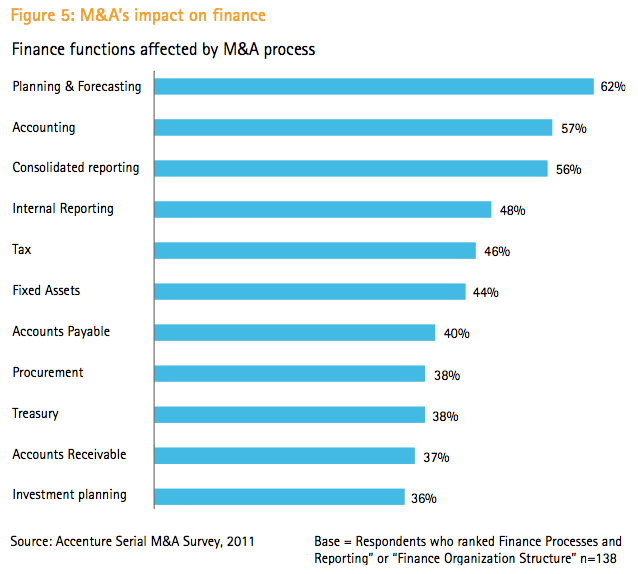

Our survey revealed that the finance function has an expanded role in many organizations. Eighty percent of this study’s participants indicated that their company’s finance function has increasing responsibility for driving programs or change in other dimensions of their enterprise that are significantly affected by M&A. These dimensions range from information technology, strategy and business, and human resources to operations and production, risk and customer service. And with economic growth on the horizon, the survey shows that some areas of finance have become particularly important. These include financial planning and forecasting, accounting, reporting, tax and fixed assets – again, areas decidedly affected by mergers and acquisitions. (See Figure 5.)

With these points in mind, we take a closer look at the five PMI enablers below.

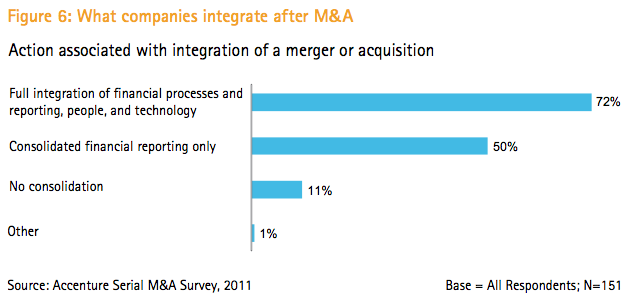

Enabler 1: Strong integration governance

Thirty eight percent of our survey respondents ranked integration of people and culture as their greatest PMI challenge, followed closely by integration of technology and of finance processes and reporting. Surmounting these difficulties requires strong governance—early and ongoing clarification of how and to what degree people, cultures, technologies and finance processes are going to be blended in the new entity arising from the merger or acquisition. The company’s leadership team should address decisions upfront such as whether the enterprise will fully integrate the newly acquired business or consolidate only certain elements. Our survey revealed varying levels of integration, which may depend on a company’s business strategy and on whether the firm has a corporate center or runs its business as a portfolio. (See Figure 6.)

Additionally, a company’s finance leadership should decide quickly which future-state operating model, organizational structure, processes and transactional and reporting systems to adopt—to say nothing of who will make up the future-state leadership. We have found that a strong governance process enables quicker decision-making. The sooner these future-state decisions are made, the less uncertainty and fear linger within employees and the faster they can align themselves to the company’s future-state goals. Understanding the company future-state vision helps employees grasp the future-state culture and adjust to it, especially when the legacy companies’ cultures were very different.

But making such decisions is not enough. Strong governance also requires ensuring that the decisions are executed as intended. Leadership teams can do this by creating a steering committee and program management office (PMO) at the finance functional level. The PMO will delegate decisions to the work team but meet once or twice weekly to escalate issues and decisions that cannot be made at the work-team level. These meetings can also be used to monitor the status of integration design and execution based on those decisions.

“Strong governance at a leading energy company” provides additional perspective on this enabler.

Strong governance at a leading energy company

When a leading energy company acquired a smaller firm in 2010, the goal was to expand its portfolio of offerings so the company could compete more effectively against major rivals. The deal was one of the largest in the industry, and the company had not made any major acquisitions in the preceding five years.

Differences between the two firms presented daunting challenges for the PMI process. The organizational cultures contrasted sharply. The acquirer had a process- and timeline-driven culture, while the acquiree’s culture could be described as more “figure it out as you go.” Additionally, the companies had different operating models—the acquirer’s dominated by a “strong finance” mindset; the acquiree’s, by a “strong business” mindset. The contrasting operating models meant that the two companies handled business transactions differently. Operational differences also raised questions regarding the roles and responsibilities of the new entity’s finance function.

Additionally, as the acquisition process extended over roughly two years, some employees were in flux regarding their job security for the duration. It is difficult for any organization to extract high performance from individuals facing such insecurity.

To surmount its PMI challenges, the acquirer adopted strong governance measures. It established an Integration Program Office (IPO) that enabled integration across back-office and front-office functions and made the decision to drive common infrastructure across the enterprise. The IPO crafted a detailed plan and timeline and began tracking progress on the PMI progress against targets on a regular basis. The involvement of the IPO enabled everyone to see the path that the new entity needed to follow, where it stood along that path at key milestones and what was needed from each function to complete the process.

Enabler 2: Dedicated team

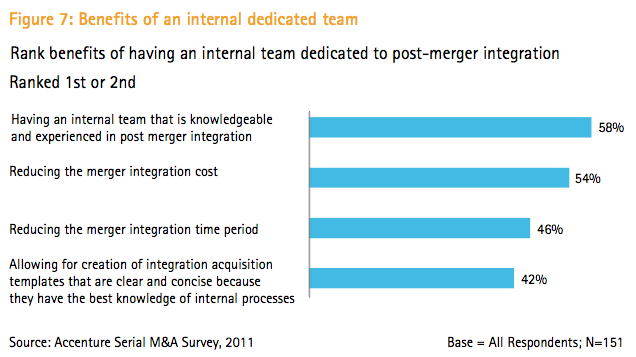

Fifty eight percent of our survey respondents said that they have an internal team fully dedicated to PMI, citing numerous benefits from this approach. Most valuable to our study’s participants, dedicated teams possess deep knowledge of and experience with post-merger integration. They also reduce the cost of merger integration by using their leading-practice knowledge and solutions from past integrations to reduce reliance on contractors and outside consultants. Additionally, dedicated teams speed integration time by utilizing methodologies, templates and tools from past integrations. Moreover, thanks to their knowledge of the company’s internal processes, dedicated teams excel at developing clear and concise Day 1 and future-state integration solutions and plans. (See Figure 7.)

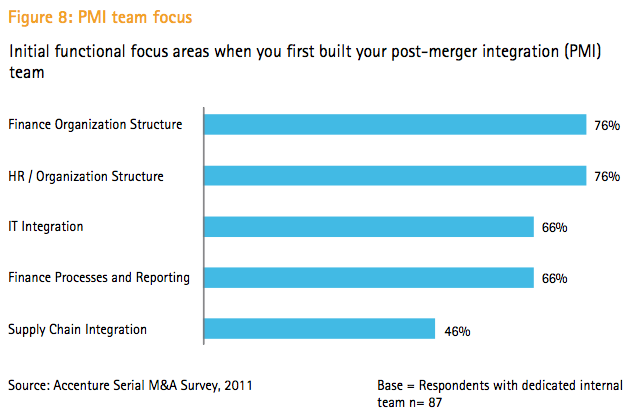

Another consideration is which functions should be included on a dedicated internal PMI team. Approximately three-fourths of our respondents cited the overall finance and human resources organizations, about two-thirds said IT integration and financial processes and reporting, and almost half named supply chain integration. (See Figure 8.)

Comparably, our experiences with clients suggest that the PMI team should comprise representatives from each function affected by the merger or acquisition—typically corporate accounting (to address chart-of-accounts mapping, compliance, external reporting and back-office functioning), forecasting (for planning and reporting), investor relations (for external reporting), business-unit finance (for management reporting), tax, treasury, finance HR and finance IT.

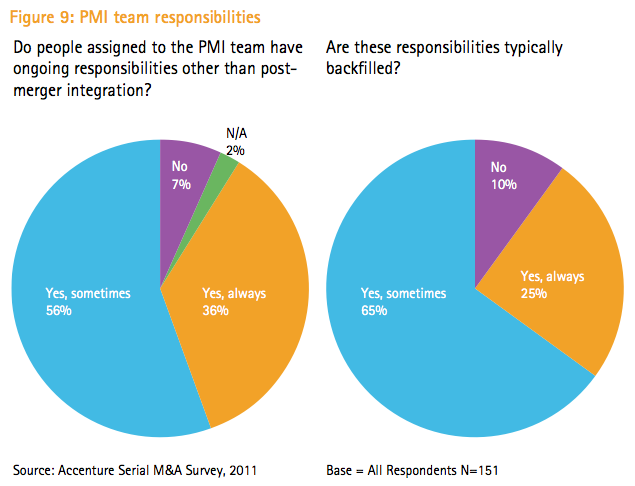

Sixty percent of those we surveyed said that they assign the same individual as team leader for every post-merger integration. Moreover, almost all respondents said that the members of their PMI team sometimes or always have ongoing responsibilities other than post-merger integration. According to these respondents, such responsibilities are typically backfilled when the team members are involved in post-merger integration work. (See Figure 9.)

For example, the consolidations and external-reporting teams of each legacy firm typically must collaborate to map each company’s chart of accounts and hierarchies to enable Day 1 and future-state financial and management reporting. However, these teams continue to be responsible for closing, consolidation and reporting for each legacy firm until the merger is closed. The key members from these teams may split their time between integration and business as usual activities. Companies may also often back-fill remaining roles on the integration team and business as usual teams with consultants and contractors to provide additional capacity.

”Towers Watson’s dedicated team” provides additional perspective on this enabler.

Towers Watson’s dedicated team

New York-based risk management and HR consulting firm Towers Watson (TW) was formed in January 2010 through the merger of Towers Perrin and Watson Wyatt Worldwide. The new entity faced several challenges, including integrating two legacy firms with very different organization structures, reducing operating costs, ensuring compliance, retaining finance talent and clarifying roles.

To surmount these challenges and ensure successful future-state integration, TW used the combined finance organization to source a dedicated team for the merger. The team included full-time finance employees who knew the business and could lead the integration design from an operational perspective. These resources were back-filled with contractors from a staff-augmentation firm. This approach freed up full-time resources for the PMI program. The dedicated team also included finance associates from the middle ranks of management. Their participation on the team gave them a sense of empowerment and ownership in the PMI effort, established balance within the finance function and injected the team with a strong operating perspective that senior leaders would not otherwise have had.

Savvy staffing of the team has paid big dividends. As one example, TW consolidated its financial statements for its first-quarter close earlier than legacy Towers Perrin had produced Financials before the merger. And everyone involved in the PMI journey experienced an increase in personal motivation, which helped them address initial challenges including interpersonal conflict and ambiguity over roles. Thanks to the empowerment of middle managers, finance associates feel proud they have a portfolio to manage. They enjoy being members of the business team, and they give the business their full support on operational decisions.

Enabler 3: Steadfast focus on target realization

The synergies that a company targets for its M&A deals depend on its competitive strategy. For example, a company whose strategy centers on growth might aim for sales and revenue enhancement through access to new customers and strive to liberate internal resources to drive that growth. Such a business might be less concerned with cost synergies. An enterprise whose strategy centers on consolidation and taking supply/capacity out of the market may seek to close plants and reduce headcount and other labor costs to drive profitability. Leaders in this enterprise may be less concerned with driving sales growth. For 68 percent of our survey respondents, achieving targeted synergies is the most critical integration factor for their company’s serial acquisition strategy—more critical than other factors including IT systems integration, speed of integration and the establishment and communication of the new organization’s structure. (See Figure 10.)

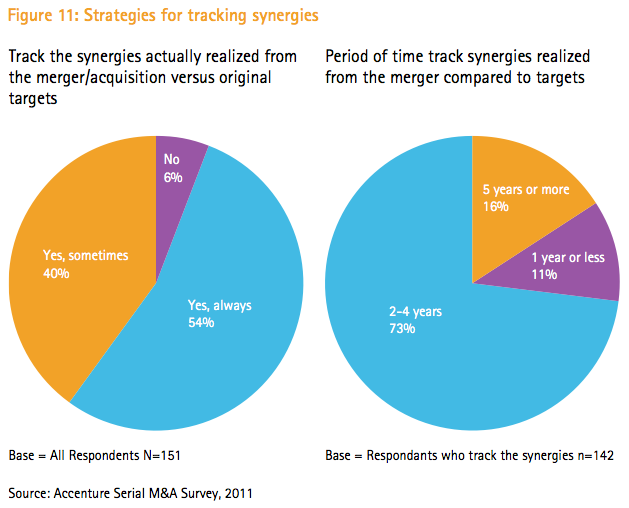

Given the importance of achieving synergy targets, it is not surprising that most of the enterprises represented in our study track actual synergies gained from a merger or acquisition against targeted synergies for two to four years after integration. (See Figure 11.)

Synergies gained are measured by tracking baseline revenue and costs with the annual accumulated improvements projected year over year against the actuals achieved each year. However, such tracking can be difficult, because the company should normalize actual results for inflation and for foreign-exchange differences if global organic and other inorganic growth through consolidations has occurred outside that merger event. When actual synergies fall short of the target, the company should analyze whether subsequent company events or strategies affected the loss of synergies, whether synergies were overestimated or whether flawed execution was truly the cause.

Of the companies we surveyed, 20 percent achieved 76-100 percent of their synergy targets, while 50 percent achieved 51-75 percent of their targets. One percent achieved synergies beyond their targets. These relatively low levels of synergy realization may stem from a complex set of forces, including the recent global economic crisis. A company that does not complete a full integration may not realize target synergies. Moreover, it can take two to three years to fully capture synergies, so some of these firms may have yet to reach that benchmark. Our survey was composed of serial acquirers that had completed at least three to five acquisitions in the last five years. Any acquirers that completed some or all of these deals in the last year may not have yet achieved the expected synergies on those acquisitions. Finally, a company may have invested less effort in synergy tracking if other initiatives (such as a subsequent acquisition) took higher priority.

“Focusing on targets during an acquisition” gives another perspective on this enabler.

Focusing on targets during an acquisition

A leading international banking and financial services organization announced that it was acquiring a retail wealth and commercial business in Asia. The biggest PMI challenges included how to integrate the businesses’ IT and regulatory reporting. Because the acquire was running its business as usual up to the legal day of the takeover, gaining access to the information and data needed for such integration was a challenge.

To ensure a successful transition, the acquirer maintained a sharp focus on realizing its target synergies. For the acquisition, the finance team was responsible for tracking and validating synergies. The leadership team reviewed synergy reports monthly, taking corrective measures as needed to close gaps between targeted and actual synergies. The company realized nearly 75 percent of its original synergy targets. After the deal was closed, it tracked revenue and cost synergies of the combined entity. According to the acquirer’s CFO, synergies should be tracked for about two years for acquirers to capture the correct values, since some synergies are realized over a period of time.

Enabler 4: Standardized PMI approach

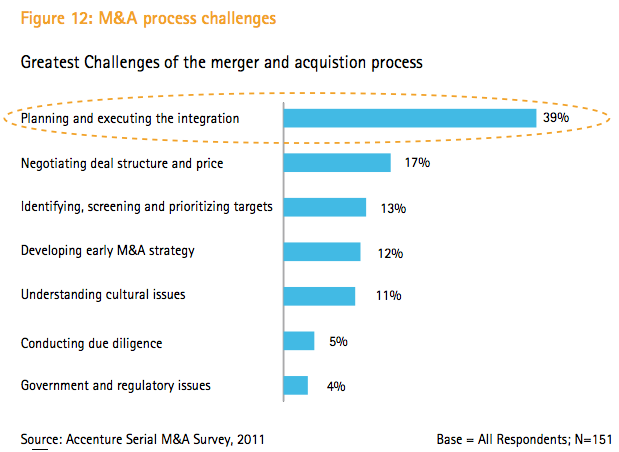

Judging from our survey findings, the greatest challenge associated with the M&A process is planning and executing the integration process. (See Figure 12.)

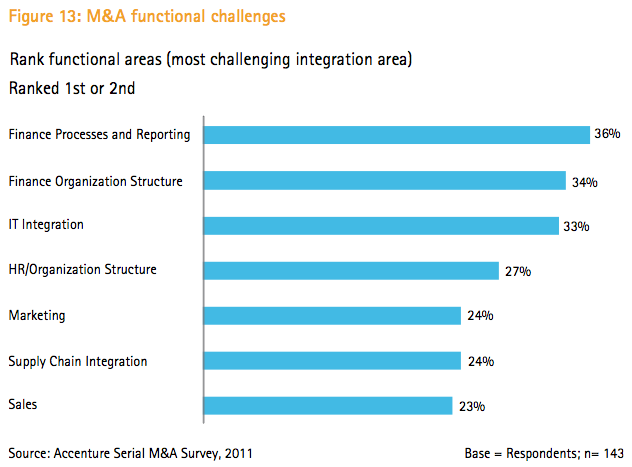

Within the realm of integration, the area cited as most difficult by our respondents is finance processes and reporting, followed by finance organization structure, IT integration and HR integration. (See Figure 13.)

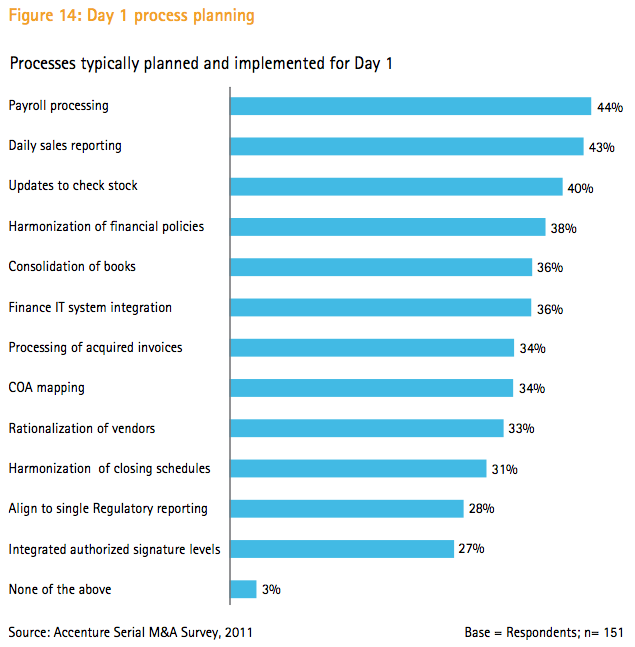

Integrating finance processes and reporting may present a particularly daunting challenge because they are paramount to supporting a company’s key external and internal stakeholders. Activities include paying suppliers and employees, collecting cash from customers, managing external reporting and compliance for the board of directors and shareholders, and managing operational reporting for the business unit leads (See Figure 14). These activities may all be operating on very different policies, processes, timelines and systems. They will have to be harmonized quickly to operate for Day 1. If any of these processes are not combined and harmonized effectively by Day 1, the company’s daily operations could unravel, risking erosion of revenue, working capital, share price and external reputation. Most of the serial acquirers we surveyed use a standard PMI approach to harmonize these processes quickly for Day 1.

A company’s PMI approach consists of standard templates and methodology to consistently implement a PMI integration. While the majority of businesses reuse planning templates for each M&A event, a company may tailor the approach depending on the business need and preference. The key is to develop an approach that fosters consistency, predictability and reusability.

We advocate a multi-phased approach to help the CFO address critical merger imperatives. This approach comprises finance-specific integration activities and organizes them into three critical areas—Day 1, Day 100 and end state—to accelerate value realization. Using this approach, companies can get Day 1 issues right and then execute the integration program immediately to maintain finance operations and service delivery. They can also meet financial information requirements as well as define and work toward achieving the future vision for the finance function. Finally, they can facilitate quick C-level decisions, actions and communication on Day 1 critical issues and synergy opportunities.

Enabler 5: Robust enabling infrastructure

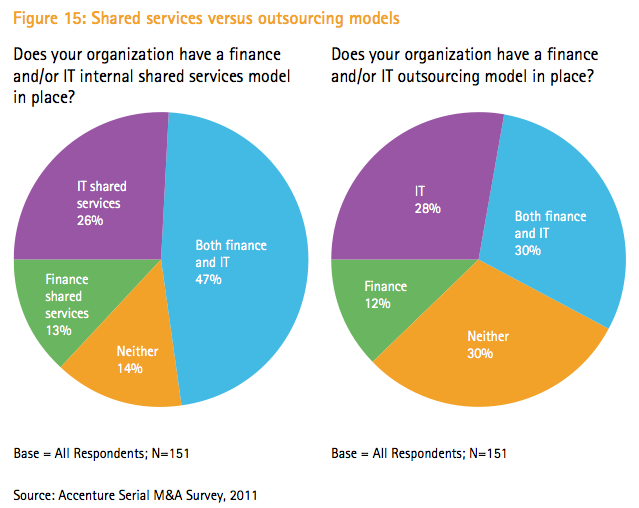

The global infrastructure that an acquiring company has built can dramatically simplify and streamline the PMI process. This infrastructure includes the company’s operating model (for instance, use of in-house shared services organizations versus outsourcing), its business processes (such as those governing back-office transactions, reporting and policies) and its IT systems (for example, enterprise resource planning (ERP) platforms).

In our survey, almost half of the respondents said they had an in-sourced shared services model in place for both finance and IT. Just 30 percent reported having an outsourcing model for these two functions. (See Figure 15.)

Companies that use a global shared services model seem to have grasped the advantages of this infrastructural component. In another Accenture study, we found that businesses demonstrating shared services mastery (defined by criteria including their ability to set and achieve objectives) are 42 percent better at facilitating PMI than enterprises than companies that are not shared services masters. A corporation that has employed a shared services model has had to standardize processes and has therefore set forth a global template. This template can be used to execute integration more quickly and effectively than a company with fragmented processes across geographies.

Additionally, companies using a global shared services model have adopted best practices including developing a set of key performance indicators, providing employee training and recognition programs, formally tracking customer retention as well as employee satisfaction and engagement, and establishing a quality control or management approach (such as ISO). Shared services masters also use a significantly higher number of technologies than other companies, judging from the shared services survey’s findings. These technologies range from automated service management tools, case management tools and customer self-service tools to portals, workflow tools and ERP systems. All of these best practices ease the transition of an acquiree to the end-state.

Conclusion

Serial merger and acquisition activity is rebounding in the current economic environment as companies acquire assets less expensively to grow and/or consolidate the market.

But despite attractive gains associated with serial acquisition, companies face increasing challenges in effective integration. Effective and efficient post-merger integration is critical to achieve the desired business value expected of the acquirer’s business strategy.

Five post-merger integration enablers—strong integration governance, a dedicated team, steadfast focus on target realization, standardized post-merger integration approach and robust enabling infrastructure—can help companies overcome challenges associated with post-merger integration and capture the synergies and other advantages these opportunities present. By mastering the enablers, companies establish a consistent, comprehensive and reusable approach for managing upcoming M&A activity, reducing risk and capturing the business value sooner than their competition.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter