Publications Consumer Currents – Food For Thought: Do Grocers Need To Reinvent Their Business Model?

- Publications

Consumer Currents – Food For Thought: Do Grocers Need To Reinvent Their Business Model?

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

Issues driving consumer organizations

By KPMG

Consumer Currents

“Companies need to ask themselves if they have truly put the customer at the heart of their business”

As Albert Einstein shrewdly remarked: “If you always do what you always did, you will always get what you always got.” In the consumer marketplace in the 21st century we live in an age where innovation and reinvention is the key to growth. That is the challenge – and opportunity.

There isn’t much easy growth in the world today – the kind that comes from opening a store here or entering a market there – which is why growth is foremost in the minds of so many executives in the global consumer industry as, in a time of great uncertainty, they try to look ahead one, three or five years.

Yet when you think about it, whether a brand or a retailer chooses to grow organically or through merger and acquisition, there is only one true, sustainable source of growth: the consumer. In an era of such significant, complex change, companies need to ask themselves whether they have truly put the customer at the heart of their business.

This is certainly the challenge facing the world’s major grocery chains. We know that growth in the grocery market is fundamentally driven by rising per capita incomes and, in many developed markets, shoppers don’t really feel much better off than they did when global recession struck in 2008. At the same time, they are facing intensifying and varied competition from discounters, online stores, price aggregators, niche retailers and services that deliver meals and recipes to the door. Millennials have made their influence felt too: their preference for eating out means that, government figures suggest, Americans now spend roughly as much in restaurants and bars as they do on groceries.

So how do grocers grow their business? There is no magic formula but the starting point is for the big chains to recognize that they can no longer try to be all things to all customers. They need to decide how best they serve their customers – do they excel at price, in-store experience or 24/7 convenience – and decide whether the business models that have served them well for so long need to be reinvented. The transition from one model to another may be arduous but we all know what can happen to businesses that stay the same in a changing market.

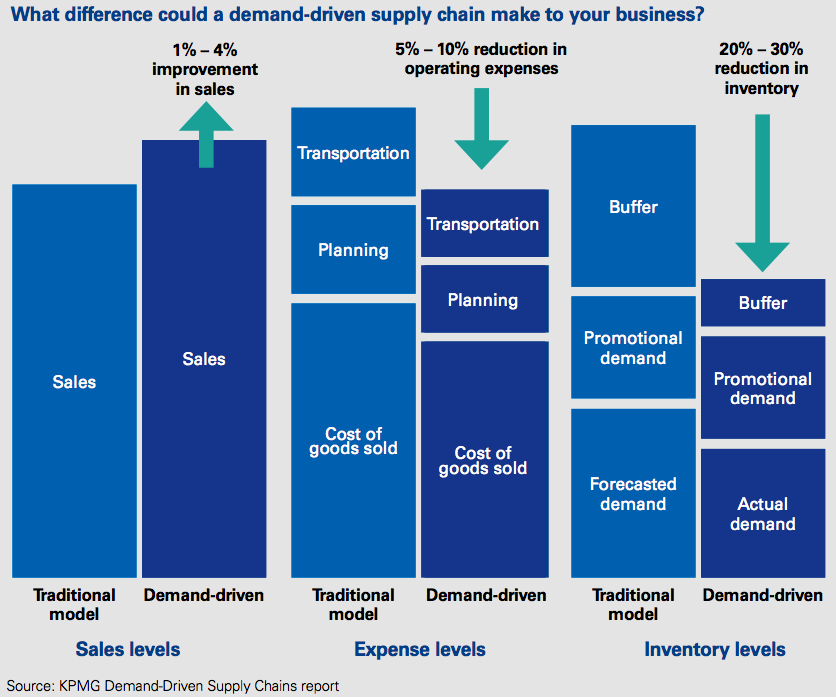

CEOs looking to identify growth opportunities have not, traditionally, looked to their supply chain. Yet, as we discuss on p14, a truly flexible supply chain that is driven by customer demand – rather than historic practice – could deliver up to 4% in revenue growth while saving millions in operating costs and inventory that can be reinvested more productively in the business.

Here, too, the process of reinvention will not always run smoothly but the key to success is to have a supply chain strategy that aligns to your business strategy, understand when change is working – and when it isn’t – and realize that creating a demand-driven supply chain is a journey not a destination. For companies that get this right, the impact can be transformative. Wowing customers by delivering the perfect order – what they want, when they want it, at the price they want and at the quality they expect – may be the best of way of creating enduring customer loyalty.

The rewards for businesses that dare to innovate are perfectly illustrated by Spin Master, the rapidly growing Canada-based toy maker. As joint CEO Anton Rabie explains in our interview on p10, it takes a particular blend of art and science to create toys that become billion-dollar franchises. They have obviously mastered this, going from a US$10,000 start-up to a US$900m revenue business in 20 years. (Willy Kruh, Global Chair, Consumer Markets KPMG International)

Wake up and smell the tea

Coffee has changed the world’s drinking habits. Could it be the humble tea leaf’s turn for premiumization?

From hazelnut macchiatos to smooth flat whites, there are endless ways for coffee lovers to get their caffeine fix – and now tea is enjoying a renaissance too. As people’s tastes change, brands and chains are monitoring consumers’ habits for revenue threats – or opportunities.

After water, tea is the world’s most consumed beverage. It remains hugely popular in India and China – although, in the latter, it suffers from a perception that it is a drink for elderly people.

The challenge in developed markets is to elevate tea to the same level of prestige as coffee, so consumers spend more – and don’t default to standard black/green/herbal varieties while basing their choice on price, Fair Trade status or decaffeination.

Move over baristas: tea sommeliers are popular in the US Specialist tea shops, with tea sommeliers taking the place of baristas, are becoming more popular. In the tea-loving UK, modern tea salons and Japanese and Russian tea rooms are now emerging. A report on tea-drinking trends by Allegra World Coffee Portal found that two-thirds of UK consumers want specialist tea shops in their towns.

The Irish have always liked their tea, as have the Dutch. Now France is turning over a new leaf, opening specialist tea salons and importing a wide range of fine teas. In Germany, consumption of herbal tea is at record levels.

In the US, Starbucks began investing in this sector 15 years ago when it acquired tea company Tazo. Within a little over a decade, its products (now sold in supermarkets) were contributing more than US$1bn in yearly sales. In 2012, Starbucks paid US$620m for the tea shop chain Teavana. It has since opened tea bars offering premium tea lattes, smoothies and loose-leaf tea mixtures created by ‘teaologists’. The more laid-back bars also offer healthy meals. Today, tea accounts for more than 10% of Starbucks’ US retail sales. Food and drink brands can see the opportunity too. Five years ago, Nestlé introduced its Special.T single-serve machine, with 25 varieties of tea, drawing on the success of its Nespresso coffee devices and consumables.

The US (the second largest importer of tea, after Russia) is a major consumer of ‘ready-to-drink’ tea (e.g. iced tea), sales of which have grown more than 15-fold over the past 10 years, according to the Tea Association of the USA. Last year, sales were estimated at US$5.2bn. Figures suggest that four in five US consumers now drink tea, with Millennials the most enthusiastic (87%).

Drinks companies are expanding their tea ranges and sell at a premium. In the US, Argo Tea is rolling out tea-based dairy beverages at select retailers. Alternatives to iced tea include organic kombucha teas, cannabidiol-infused teas, and a sparkling, flavored Chai tea.

“The growing taste for tea in so many forms and across so many markets is a massive opportunity for retailers and brands,” says Mark Larson, KPMG’s Global Head of Retail. “We have seen the premiumization of wine in the 1990s, of coffee in the 2000s. Could it now be tea’s turn?”

UP FOR A CUP

Number-crunching the tea boom

10 cups – the amount of tea consumed in Turkey, per person per day.

11m – gallons of tea consumed every day in the UK

100% – forecast growth in US tea sales in next five years

US$9.7bn – value of retail tea sales in China in 2014

Next tech Facial recognition technology

Once the stuff of science fiction, facial recognition technology is now a reality. Global software company Computer Sciences Corporation estimates that 27% of retailers already use it in store.

At its most basic, facial recognition alerts retailers to the presence of known shoplifters, but some applications offer much more.

Startup Emotient recognizes “the seven primary facial emotions: joy, surprise, sadness, anger, fear, disgust and contempt” in customers’ reactions, helping retailers offer a more personalized service and boost sales. Some shoppers are skeptical, however. In one UK study, 68% said they found the technology “creepy”, while 73% felt uneasy about staff greeting them by name.

As with any technology used to track behavior and profile people, privacy is an issue. Applying the technology more creatively, as Pizza Hut does with its ‘Subconscious Menu’, which uses an algorithm to choose pizzas for customers based on their eye movements as they scan the menu, may help retailers use the technology without alienating customers.

Many consumers value their privacy while shopping, so retailers should take appropriate measures to ensure they preserve it. George Svinos, KPMG in Australia, says: “This intriguing technology is likely to evolve in more exciting ways in the future. But it should be clear to customers how their data will be used, and they should be able to opt in or out of facial recognition.”

Direct or indirect?

Cutting out the middle man to sell straight to consumers may sound like an easy win for manufacturers, but there are risks involved

Brands have been selling direct to consumers since the 1920s, when Britannica hired 2,000 salesman to sell encyclopedias door-to-door across America. Yet almost a century later, as online sales grow faster than in-store purchases, more brands are seizing the opportunity. By cutting out wholesalers and retailers, they believe they can drive up sales, raise brand awareness and increase their margins.

This trend is not confined to one sector. Food giant General Mills expects e-commerce’s share of sales to grow from 1-2% to 5-6% in the next few years. Nike aims to expand online sales from US$1bn in 2015 to US$7bn by 2020, using 3D printing to offer customization and slash delivery times. The likes of Burberry have flourished, supplementing bricks and mortar with strong online sales.

“Technology enables manufacturers to interact directly with the consumer”, says Peter Liddell, Partner in management consulting at KPMG in Australia. “It allows them to access a global marketplace and to move beyond their traditional markets and bricks-and-mortar stores.”

The attractions to manufacturers are clear. Selling direct saves money, reduces logistics and lets them retain margins on each sale. They can also be more price competitive and enjoy more control as the fight for shelf space becomes less acute. Direct access to a wealth of customer data can sharpen marketing strategies.

Yet selling direct will not, Liddell says, suit every brand. Many are looking to move beyond bricks and mortar, not replace it. For most, it’s about finding the right mix. “Not every manufacturer is geared up to manage the end-to-end supply chain”, he says. Distributors and wholesalers manage many strategic and business decisions for manufacturers, such as pricing, effective fulfilment and procedures for handling refunds.

“The key questions manufacturers should ask before they sell direct are: how will they price their products now that they’ve cut out the middle man? And how will they ensure integrity and quality of product through the value chain?” says Liddell. “Manufacturers will have to be sure that when the product leaves their depots, it reaches the customer as expected. If service levels dip, there could be a huge impact on brand reputation.”

While selling direct could work well for giants, Liddell says, lesser-known brands “need intermediaries to help heighten awareness of products.” This is especially true for start-ups. Pure play etailers such as opticians Warby Parker and footwear company Zappos grew rapidly selling online, while Graze, which started out selling online subscription boxes of fruits, nuts and grains in 2008, now sells around 3m snacks through UK supermarkets.

Manufacturers must assess how selling direct will affect existing distribution channels. Some brands have asked stores to help fulfil orders; others report that better brand awareness has stimulated sales in stores. “I expect direct sales to put pressure on indirect”, says Liddell. “As consumers become more confident that they will receive quality items, direct-to-consumer will really take off. In five years’ time, there will be a fundamental change.”

Analytics in marketing

There’s no guaranteed way to attract new customers but the power of analytics can help you target the most likely people, says Julio Hernandez, Global Lead for KPMG’s Customer Center of Excellence

No company in the consumer industry can grow solely by retaining customers. In a fast-moving marketplace, where brand loyalty is no longer the force it was, and with consumers enjoying more choice than ever before, brands and retailers need to acquire customers to flourish. It’s true that this can be expensive. Companies must build brand awareness through research, advertising and marketing. Some of these campaigns will succeed, some won’t. But it would be misleading to assign the entire cost of such investments to customer acquisition. In his influential book How Brands Grow, Professor Byron Sharp of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute at the University of South Australia argues that the prime purpose of marketing is to make sure the consumer remembers the brand when they’re in the store. If they don’t remember you, they’re not going to buy you. So these campaigns don’t just reach out to new customers, they jog the memories of people who have already bought the product.

So let’s not fixate on calculating the cost of acquiring each customer down to the last fraction of a cent. It is far more productive to use analytics to understand which marketing techniques work and which don’t and react accordingly. With faster, richer, more measurable feedback from customers, it is easier for companies to, for example, modify special offers when necessary. In an age when consumer preferences can fluctuate wildly and quickly, analytics also make it much simpler – and faster – to model new patterns of customer behavior.

“Using analytics to target prospects who resemble their best existing customers, brands can improve conversion rates”

Analytics can help brands gain much deeper insight into their customers – and use that data to inform their marketing strategies. Companies can segment their customers at a micro-level – by demographics, spend, location, channel, responsiveness to incentives and social media network – and use that profile to directly target those who resemble their best existing customers, improving their conversion rates. For other brands and retailers, their analytical focus is to understand what customers aren’t buying and why – and feed that back into their sales and marketing strategies.

The secret to successful analytics has less to do with data or technology than with managers who have the creativity, flexibility and insight to understand how to get the most out of it. Companies that get it right can resolve the conundrum that has haunted marketing departments for almost a century – in the famous words of the pioneering American retailer John Wanamaker: “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted, the trouble is I don’t know which half.”

Time for grocers to think the unthinkable

Supermarkets will need new, more customer-centric business models to prosper in an ever-changing market

“Are you in the business of selling groceries or feeding families?” That is the question Mark Essex, Strategy Group, KPMG in the UK, would like every supermarket to ask itself. The answer, he suggests, could lead them to reconsider their business model.

“If our large food retailers changed their business model to one focused much more on the consumers’ needs, they could achieve more profitable, sustainable long-term customer relationships,” says Essex. “In the UK, the current farm to store or farm to doorstep value chain is dominated by the top five (Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, Morrisons and the Co-op) which have 77% of the market. They have improved the variety of our diets, stimulating our senses with a fantastic amount of choice. We have never had so much access to what we want, when we want it. And every year, new tastes and sensations arrive. This is expensive to provide – the scale and scope of all that inventory creates a lot of waste through the supply chain from farmers discarding apples that aren’t spherical enough to shoppers discarding uneaten produce they bought on promotion but didn’t need. That waste is funded by consumers, in the price they pay.”

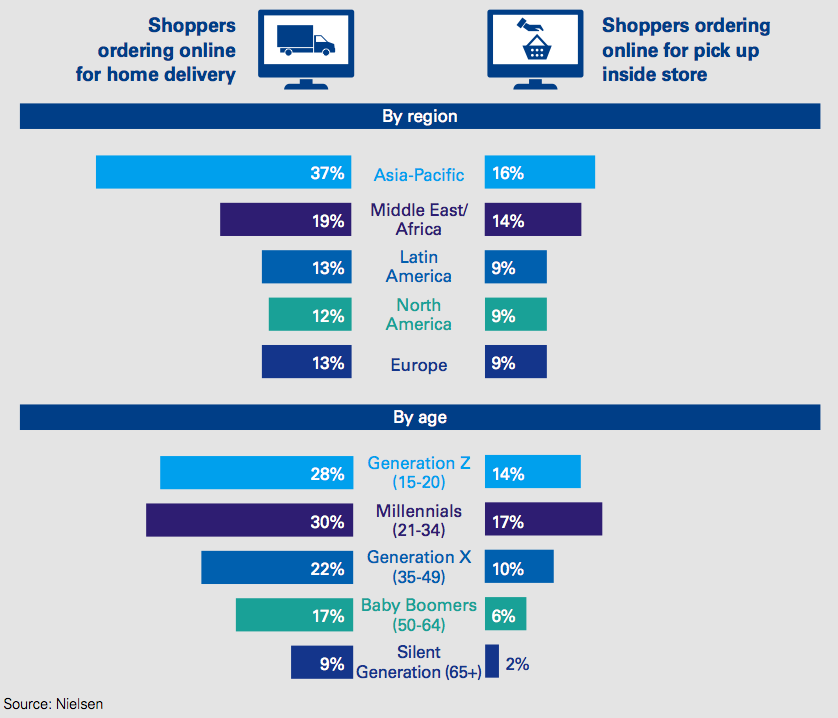

The quest for convenience

The boom in online delivery in some markets, notably the UK where it accounts for 6% of grocery sales, marks a step change in convenience, but Essex thinks supermarkets could take this further. “Consider how much work the shopper has to do to feed the family. They have assessed the needs of the family based on social diaries, specific requirements – such as dinner parties and packed lunches – decided how many meals will be needed, consulted with the rest of the family and decided roughly what to make. They have checked their inventory of fresh and dry items including those things they don’t purchase very frequently. After considering the meals, the recipes and the food needed versus the inventory available, they prepare a list.

“By the time they have evaluated the offers, decided what to order from whom and how much to pay, this could add up to two hours a week, more than 100 hours a year, on a spend of perhaps US$10,000 a year,” says Essex. Looked at this way, the process sounds absurdly protracted, complex and labor intensive, especially when most shoppers buy many of the same goods week after week. And that’s why, he says: “It doesn’t have to be this way. What if supermarkets did some of this work? What if my family paid the supermarket US$750 a month to feed us? Much of the supply could be planned in advance, with weekly tweaks to suit particular needs. The supermarkets could then provide tailored food, or meal kits for my family according to our nutritional, ethical or environmental priorities. They could tie up with a takeaway business and send Saturday’s food hot – or deliver a dinner party kit with matched wines.”

In this brave new world, Essex says, grocers could turn some of their expensive out-of-town real estate into food showrooms that work like car dealerships. They could add some theatre to the experience – Hy-Vee, the American employee-owned supermarket chain helps shoppers find the nearest store with a chef in residence – and offer goods for the discerning shopper that are hard to market online. If they like the look of a specialty cheese, they could have it factored into next week’s meal plan by clicking the QR code.

And if we immerse ourselves in this reality, we find other opportunities to improve the experience. If grocers enjoy a deeper relationship with the customer, they won’t need as much disposable packaging. Milk and eggs could be delivered in re-usable containers or already packed in the refrigerator shelf: the whole shelf is switched on delivery. Fresh vegetables are taken straight from the wholesale container into the store cupboard. This is good for the environment, reduces costs and gets rid of the work required to dispose of that waste.

To make this system work, the retailer would need to invest in getting to know the customer in granular detail – and use that data to help the customer. Yet Essex is convinced it would be worth it: “It’s a shared investment. Once I’ve subscribed, as long as my food supplier performs, how likely am I to switch providers? In the UK, we only change our banks every 17 years. If I stay with my grocer for say 20 years, at $10,000 a year, that’s $200,000. The customer investment should be on a par with that made by your luxury car dealer.”

“Food retailers could build more profitable, sustainable, long- term relationships with consumers”

This model would not work for every product, every supermarket or every shopper. Some customers would not want to cede that much control. Others are happy to nip into a store on their way home from the office – for example, 40% of Waitrose’s sales in London come after 5pm. Yet, the model could work for a portion of the weekly shop – do shoppers really need to reconsider, on a weekly basis, what brand of frozen peas they prefer? And, as Essex says: “If families were willing to subscribe to their grocers, as they do to their entertainment suppliers, the supermarkets would really own the farm to plate chain.”

Essex’s vision is radical, possibly too radical for many, but there is absolutely no doubt that the time has come for supermarkets to think the unthinkable. As Madeleine Chenette, Executive National Director of Strategy Advisory Services at KPMG in Canada, says: “The need for supermarkets to examine their traditional business models, given the many challenges they face, is common to all developed markets, and is as urgent in North America as it is in Europe.”

Austerity-busting growth in the major grocery markets has come to a halt. The threats are coming at traditional supermarkets from all sides. Discounters have wooed budget-conscious consumers – in the UK, where they have been especially aggressive, they took US$2.8bn in sales off the competition in 2014. Digital disruptors such as online delivery specialists Ocado and Peapod have found a profitable niche.

Online aggregators such as Instacart, FreshDirect and AmazonFresh are in expansive mode. And then there are the fresh ‘recipe box to the door’ providers such as HelloFresh, which now has subscribers in seven European countries, Australia, Canada and the US. On top of all this, the Millennial generation loves eating out – and government statistics show that America now spends roughly as much in restaurants and bars as it does on groceries.

What’s driving consumers?

Not all of these challengers will succeed but they will intensify the battle for market share. So how should supermarkets respond? Paul Martin, Managing Director of Insights, KPMG in the UK, says a completely fresh start is required. “This isn’t something you can resolve by throwing a lot of digital technology at it, nor can they go on trying to be everything to everybody. The biggest step they need to make is to stop being product-centric and put the consumer at the very heart of their business model.”

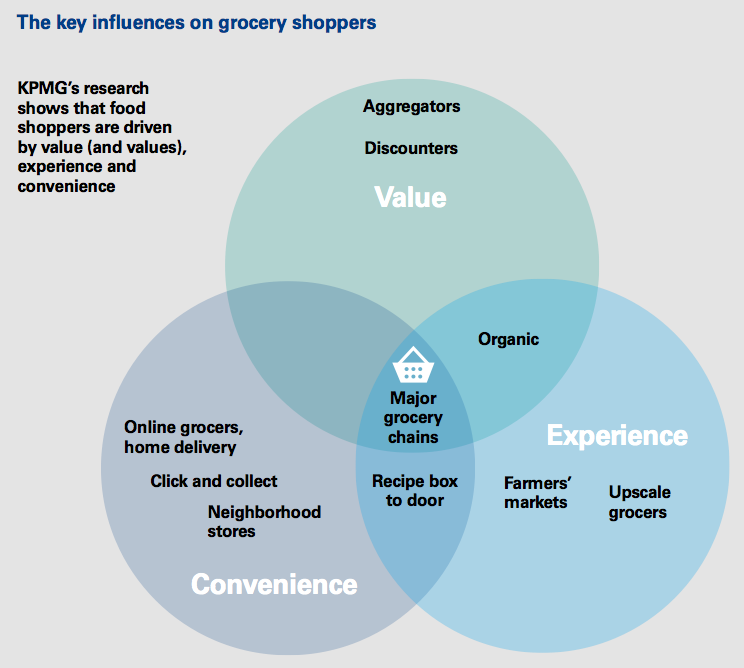

KPMG’s research has identified three key factors that drive shoppers: value, convenience and experience.

Value-driven consumers want the lowest possible price – though they are becoming savvier about the different offers they encounter – but they can be driven by values: social, environmental or reflecting their view of their social status. To satisfy these shoppers, grocers will need to be transparent about their supply chain and source products ethically.

Convenience spans the small format store nearby that offers a limited choice, the weekly online shop for home delivery and Essex’s ambitious scenario of an entertainment services-style subscription model.

For shoppers who are driven by experience, it’s about how they feel when they visit a store or buy online. As Martin says: “Shoppers enjoy going to Waitrose stores and because of that they’re prepared to spend more.” If they can’t park, get stuck in interminable checkout queues, find the staff disagreeable or discover the product they wanted is out of stock, they’re very unlikely to return. The challenge for those who get it right in-store is to apply that to what they do online. These distinctions sound simple enough but shoppers can be driven by one, two or all of these factors at different times. And sometimes these drivers interact in unexpected ways. For example, Texan supermarket H-E-B uses the fish-on-ice strategy perfected by Whole Foods to create an aura of freshness in its outlets, but it keeps the in-store experience simple and bombards shoppers with coupons and free offers. This defiantly old-school approach resonates with its audience – it consistently scores well on the Market Force consultancy’s Delight Index of American supermarkets.

Defining a value proposition

“To be successful, grocers have to be very good at serving one of those three drivers,” says Martin. “And they need to be realistic about it, there’s no point trying to convince customers you’re the cheapest if you’re not – and can never be. The analogy I like to draw is with aviation. A typical budget airline will have its planes in the air 14 hours a day, compared to eight hours a day for a traditional airline. You don’t need a Nobel Prize in Economics to understand why traditional airlines find it so hard to compete on cost. What you don’t want to be is stuck in the middle of the market, where you are not exceptional at anything.”

Each grocer will have its own answer to the eternal question: what value proposition will you deliver to the customer? A grocer might excel at one driver but look to strengthen its offering elsewhere. So, for example, discounters, having made inroads into the UK market, are now moving upmarket, investing millions in stores that offer self-checkout, wider aisles and bakeries, deluxe food and revamped wine departments as they strengthen their pitch to the British middle-class.

Whatever strategy they choose, supermarkets need to be ready to re-examine the industry’s traditional practices. The race to open large hypermarket estates, so characteristic of the 1970s and 1980s, is now over and Martin estimates that, in the UK, leases permitting, up to 30-40% of these outlets could be disposed of in the next few years. Some properties could be repurposed to offer a different kind of experience and goods or become distribution fulfilment centres but even if they do, they will own a lot less square footage of retail space than they do today.

The right product selection can make the difference. “The multiples need to know their authoritative range of products,” says Martin. “If the rule of thumb is that 1,400 SKUs cover 80% of a food shopping trip, does it make sense to have 3,500 SKUs in your store? Understanding your authoritative range of products could reduce complexity – and complexity is always costly – and help you compete.”

There are signs that such a reappraisal is underway: last year, Tesco announced plans to cut one third of its 90,000 products. In the quest for market share, the supermarket had ended up offering 228 varieties of air freshener. Choice can be a virtue but consultancy Kantar Retail estimates that British households only buy 400 products a year and 41 in their weekly shop. As Chenette says, reducing the range of SKUs could be part of a strategy to encourage shoppers to buy private label goods, on which grocers make better margins.

“If 1,400 SKUs cover 80% of a food shopping trip, does it make sense to have 3,500 in your store?”

Convenience is a trend that harks back to the past and points towards a digital future. “For a lot of people, it’s about a return to the experience we had in Britain in the 1950s, where you went to the corner shop and the owner knew your name and what products you bought,” says Martin. Yet for some consumers, convenience could also be ordering groceries on a smartphone during their commute home via a virtual online grocery store.

The one area where rethinking the traditional model is particularly perplexing is online shopping. In the race for convenience, many British grocers have ended up offering a proposition – delivery to the door – on which making money is a challenge. “You need at least US$140 per order to make a profit on home delivery in the UK. The average order size is nearer US$105 so grocers are losing money on each delivery,” says Martin. The success of Ocado, Britain’s largest pure play online grocer, shows that home delivery can pay – but it only reported its first pre-tax profit last year, driven by a 30% surge in new customers, and its pre-tax margin was just 7.5%.

Investing in-store

In France, supermarkets have outsourced home delivery to the consumer by focusing on ‘click and drive’, enjoying substantially higher margins on each transaction. In the UK, where the shopper has grown accustomed to home delivery, it will be hard for grocers to change their model to ‘click and drive’. And in most developed markets, grocers will feel obliged to offer both in certain locations.

“This option is very attractive to shoppers who just want to simplify their life,” says Chenette, “but this model is difficult to make money on. The key is to find different ways of using the network – maybe with other partners – or introducing pricing options at peak times.” Under Essex’s subscription model, in which the shopper might change their grocer no more than every 20 years, home delivery makes more sense as a customer investment.

The traditional grocers’ greatest asset as they look to build a sustainable business model may be the very bricks and mortar stores that, only a few years ago, were being written off as obsolete burdens that were expensive to maintain. The evidence for a revolution in consumers’ shopping habits, a fashionable narrative in the UK, is conflicting.

Research by Kantar Retail doesn’t support the conventional narrative that Britons are shopping more frequently, buying smaller baskets, running to convenience stores, scouring different shops for value and have abandoned the weekly shop to “buy like the Germans”, as one analyst put it. Their study suggests that in 2014, Britons made 221 trips to the supermarket a year – the same number as in 2010. What has changed is that their top-up shopping accounts for a slightly higher share (61.2%) of overall spend than in 2010.

“The sizzle that sells the sausage”

What isn’t different, even in Germany, where shoppers make 20% fewer trips to the supermarket than in 2001 but still visit them 217 times a year, is that grocers have hundreds of opportunities to sell to consumers.

For shoppers, an experience that makes them want to come back can mean anything from spending less than an hour in-store, browsing over a sumptuous delicatessen or being able to make their purchase through their tablet. Colorado supermarket chain King Soopers has made the family shop less arduous by offering car-shaped carts fitted with videos to entertain children.

Yet are grocers making the most of these two hundred and something opportunities to wow the customer? Essex isn’t convinced, saying: “They need to remember it’s the sizzle that sells the sausage.”

For some grocers, these visits could be their chance to sell on quality to discerning customers. The in-store ambience is crucial to this approach – which is why so many grocers have experimented with using fresh food scents to titillate shoppers’ taste buds.

A 2014 report by consultancy Canstar Blue suggested Essex may have a point. The survey of 2,500 Australian shoppers found that 62% were unhappy with the length of checkout queues, more than half were annoyed to find a product out of stock and 38% were irritated by self-service machine errors. These findings, echoed to varying degrees in other developed markets, suggest that too many grocers are alienating shoppers rather than wowing them. For Chenette, one obvious remedy stands out: “Companies need to change their mindsets and invest in their in-store staff, educate them and create learning platforms so they can continue to enhance the customer experience.” Some grocers have such programs in place, but many have not seen this as a priority.

Warehouse giant Costco shows what can be done – cutting costs on almost every aspect of its operation means there’s not much sizzle in its warehouses but it has committed to “maintaining compensation levels that are better than the industry average” to reduce churn, satisfy employees and improve the shopping experience. A typical Costco cashier is paid around US$49,000 a year and generates US$610,000 in revenue in that time.

With the right investment in staff, Chenette says, grocers can look to a more sophisticated sell. “The shopper isn’t loyal to one grocer – they’re going to different stores for different things – but one way to own the customer, is for grocers to reinvent themselves so they’re selling solutions not products – so, to take an obvious example, presenting a recipe to a shopper and telling them they can buy everything they need to make that in-store.”

If grocers could, as Nielsen has suggested, position their stores “as the social centers of communities, where neighbors can feed their bodies with nourishing food, their souls with good conversation and their wallets with great deals”, they would find it much easier to build customer loyalty. They could also make more money – selling in-store is generally more profitable than delivering to the door.

With the right business model, a willingness to innovate, and a clear sense of where their investment will be most effective, grocers can build a sustainable business.

Chenette suggests that grocers might decide that it makes sense for them to own the supply chain “because it will help minimize their risk and because the source of their production is an increasing concern for many consumers.” Equally, they might decide to collaborate more closely with partners in their supply chain – or, as Essex suggested, with interesting companies from outside the industry. As he says: “If the focus is on ‘well-being food’ which lengthens your lifespan, a grocer could tie up with a drugstore or a life insurance company.” They might even want to acquire some of the disruptive competitors trying to win market share off them.

The future looks considerably more complicated for traditional supermarkets than the past. Moving to a new business model won’t be easy but it is achievable. As Martin says: “Grocers may come at this from a different starting point but they have one thing in common. We are moving from a scenario where there was one successful business model to one where there are many models.

“What separates the winners from the losers won’t be technology – though that can help grocers power the solution – or traditional demographics but the mix of convenience, value and experience that satisfies the customers they’re aiming to serve.”

Minding the store: Investment in in-store staff could help grocers build customer loyalty.

Five key learnings

1. Grocers in developed economies cannot flourish purely by investing in digital technology. Selling online can grow revenue but grocers still need to think long and hard about their business model.

2. Consumers are driven by different desires and needs. KPMG’s research shows that the three fundamental drivers for shoppers are value (and values), convenience and experience. Grocers need to decide which of these they excel at.

3. Being everything to everybody is no longer an option. Competition is intense and varied and supermarkets need to decide what model best suits their business and prioritize their investment accordingly.

4. Investing in sales staff is key. With the right calibre of motivated, knowledgeable staff, grocers could build loyalty and put their stores at the heart of their communities.

5. Success will look different for different grocers. The era when one business model guaranteed success is over. Grocers need to look beyond demographics and technology and develop their own blend of value, convenience and experience.

“You’ll find a unique story behind every single innovation in our product library”

From small beginnings, Canadian toy maker Spin Master has become a huge player in the global kids’ entertainment sector. ConsumerCurrents talks to Anton Rabie about innovation and the value of inventors

The fact that toy giants Mattel, Hasbro and Lego are involved in the worldwide product roll-out for the new Star Wars movie will probably come as no surprise. But so too is Spin Master, a Canada-based children’s toy and entertainment company that may not yet have the revenues of its larger rivals, but has proven a disruptive force in the children’s toy category. Analysts predict 2015 revenues for the company at more than US$900 million. That is up from US$812 million the previous year, translating into double-digit growth fueled in no small part by its Star Wars-branded flight toy and a 16-inch animatronic Yoda.

Those revenue figures put the newly public company (which listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange this past summer) within the top five toy companies globally, if not yet the top three.

That Spin Master continues to grow in a consumer category notorious for generally flat year-on-year growth is impressive. Kids can, after all, be fickle and as a result, product life-cycles incredibly short.

Launching a US$10,000 start-up two decades ago, Anton Rabie and his childhood friend Ronnen Harary – they also attended Western University Ontario together – hit the jackpot with a novelty product called Earth Buddy. It was a nylon-stocking-covered head of sawdust topped with grass seed that grows to emulate hair. As the product approached the end of its life cycle, the good friends, bucking the trend of Canadian companies operating solely as distributors of American-made toys, sought out ideas from inventors around the globe. Their goal: to create, design, manufacture and market innovative toys.

And Spin Master has done just that, with such brands as Air Hogs, high-performance remote-controlled vehicles with lifetime product sales of US$1bn; its Zoomer line of robotic animals that won several Toy of the Year awards; and Paw Patrol, an entertainment brand which launched as North America’s #1 preschool TV show and toy line simultaneously. The latter represents a particularly attractive launch strategy for the company. Since forming its entertainment division in 2008, Spin Master has produced five TV shows commercialized through toy products and licensing in non-toy categories.

Spin Master now has four business units (Remote Control and Interactive Characters; Boys Action and High-Tech Construction; Activities, Games, and Puzzles and Fun Furniture; and Preschool and Girls), from which it launches two to three new brands each year. It has design and development teams in Toronto, Los Angeles and Asia, and a global workforce of 900. At its headquarters in Toronto, ConsumerCurrents caught up with co-CEO Anton Rabie. With the unbridled enthusiasm of an entrepreneur on the cusp of a billion-dollar children’s entertainment empire, Rabie explains Spin Master’s high batting average in bringing retailers the next hot toy brand.

We’re sitting down just before the holiday shopping rush. What kind of year do you expect for the toy category?

The toy industry is a mature one; it has been around forever and is very stable. The first big change was a couple of decades ago with video games, but even then the traditional side of the toy industry remained flat. The same held true after the arrival of technology like the iPad. Yet this year, toy industry revenues are up. I attribute the lift to a number of factors: excitement around Star Wars; the improvement in toy innovation; and also the trend for parents encouraging kids away from screens. The last few weeks of the holidays will be important, but the industry is up so far about 4% to 6%, more than it has been in a decade.

You mentioned Star Wars: [Episode VII – The Force Awakens]. How did Spin Master end up partnering with Disney on the film, with toys like a remote-controlled Millennium Falcon?

Disney, they are the king. Our competitors work with them too; Hasbro has been doing a nice job on the main action figures. But we played to our strengths in animatronics with an interactive Yoda. We’re also the number one toy company in flight, with Air Hogs; that is how we ended up with the remote-control Millennium Falcon. We figured out which segments we could win the license for.

Geographically, where have you been seeing most growth?

A lot of it is international. A decade ago, the split between North America and global would have been about 80/20. Now, approximately 30% of our business is outside North America. Our goal is to grow international sales to 40% of total sales over the next few years. I think part of the reason for that is content. Thirty years ago it was very difficult for a TV show to go global but now that content can travel the world very quickly because of digital distribution models. That has helped a company like ours. We partnered with Keith Chapman, who had so much success creating the preschool series Bob the Builder, on a TV show called Paw Patrol. Within months, it was being broadcast in more than 70 countries. Now we see Paw Patrol-themed birthday parties around the globe, because… think about a kid in Australia – the emotional connection he has with the brand is the exact same as a kid in Europe or as a kid in America.

So Spin Master owns the intellectual property on these shows, allowing it to concurrently develop toys and license out non-toy opportunities?

Right. In some ways, the way children play hasn’t changed, but in an important way it has, which is why the model works so well. Kids still enjoy role play but what has changed is how obsessed they’ve become with aspirational characters. When our shape-shifting action figure brand Bakugan was big, kids knew everything about every one of the characters’ powers and features. Children really immersed themselves in that world through the TV series, web and even ancillary products like pyjamas and bedding. That is why over the last decade we’ve really become a children’s entertainment company.

But kids can be a pretty tough audience. How do you source ideas for a brand they’ll respond to?

The thing that is unique about our company is that we’re known for rewarding ideas from the outside. We do a lot of R&D internally as we’re fortunate to have world-class inventors, designers and engineers, but a lot of it also happens on the outside, because we’re driving both.

The world has become so flat that we feel we can access tech and IP from so many places. And so we really embrace the relationship we have with all kinds of inventors around the world, from an engineer in China to an illustrator in Los Angeles. You’ll find a unique story behind every single innovation in our product library that involves different inventors, engineers and other partners.

Tell us one story of that innovation.

Bakugan is a great example. An American illustrator had created this very, very rough sketch of a ball exploding into something like an action figure. The design and engineering would require very small parts, and so we went to Japan, where we accessed the expertise of inventors and engineers. We also partnered with Sega Toys in Japan and Corus in Canada on an animated TV show. That is how Bakugan became a billion-dollar franchise – but it started as a spark from this one inventor.

And when you look back at the original seed – the sketch – you can see how much it must have changed to get to its final iteration. So, we think about our approach in terms of mental tinkering, where all these different people put their fingers in. What if we did this? What if we tried that? We can do that because there is no ego about whose idea it is since our ideas come from anywhere.

“We’re not afraid to do acquisitions with what I call ‘hair’ on them. That can become an advantage for us”

How much revenue does Spin Master allocate for product development annually?

We spend 2% of sales on product development. The interesting thing about Spin Master is if you look at comparable companies we actually spend less, even though we’re known for our innovation. As I mentioned, we do a huge amount of R&D internally, but part of the cost for us is actually variable because we’re paying inventors royalties based on sales. In essence, we outsource some of the product development to our inventor network. So we have a fixed cost component and also a variable cost.

The outside channel also helps us to constantly innovate and diversify. We don’t have to worry as much about a toy’s life cycle because we have so much in the pipeline.

Beyond efficiencies in product development, what other advantages come from forging relationships with so many outside partners?

We’ve found that when we show an innovation in a kids’ toy category that we haven’t been in before to a large retailer, they are willing to embrace it in a way they might not if we were a different company. Some of our competitors are known for one category of toy, so it is harder for them to go to a buyer and say, ‘We’re doing this now.’

We’re known for working with different inventors and breaking through into different categories, so it is an easier sell.

Still, developing a winning idea must be very difficult to do. How much of it is an art versus a science?

It’s really a combination of both, but normally art kicks off the process and the reason I say that is because no brand has ever been conceived exactly the same way. The science comes later once an idea has been given the green light, and you have those checks built in along the development. Then it is a balance between the two, flipping back and forth between art and science, science and art.

Spin Master has also made a number of acquisitions – most recently of Cardinal Industries, a game and puzzle company in the United States with revenues in excess of US$50m. How important is acquisition to the company’s growth?

This is an area of our business on which I spend more and more of my time. In the last 10 years, we’ve made about 11 acquisitions, but in the last couple of years, we’ve made more than ever. We’ve also become more acquisitive. When some companies start looking for acquisitions, they hire an investment bank, but we take a different approach. First, we have a team internally that is probably bigger than those of our larger competitors. They are four people with deep industry knowledge and 10 years’ experience with Spin Master. Second, while we look for great brands to acquire, we’re also not afraid of looking at small deals – and a lot of them, too. We’re now set up to do about three to five small to medium-sized acquisitions per year pretty comfortably. We’re also not afraid to do acquisitions with what I call ’hair’ on them. That can become an advantage for us because there are usually fewer bidders. You can also end up paying less.

Can you give us an example of such an acquisition with ‘hair’ on it, i.e. one that on the surface wasn’t so attractive?

Toy construction set manufacturer Meccano (known as Erector Set in North America) had hair all over the place. The company had a factory in France that no one wanted to deal with because it is unionized. But we’re not afraid to do the work first before we dismiss something just because it looks like a hassle. We really try to uncover the value equation by asking the right questions. What if we put our robotics division on it? How else can we put our infrastructure on it? What intellectual property would it provide? How could it diversify us? When you do the extra analysis you sometimes discover an opportunity you wouldn’t have otherwise noticed.

I also don’t delegate the finesse of the deal – I make sure I personally oversee it. Inventors have these emotional triggers related to ego, family and legacy. I take the time to understand what those are and construct a deal that makes them happy. It is a competitive advantage to keep inventors with their company. By taking care of the back-end, they can spend more time on the rainmaking, on product and licensing. We approach acquisitions with the same mindset with which we run the business – that ideas can come from anywhere.

How consumer driven are you?

Reinventing the supply chain so it is truly demand-driven isn’t easy but, if you get it right, it can transform your business

“Imagine you are standing at a bus stop. Your smartphone vibrates to tell you that big rain clouds are only 15 minutes away. You call a company to order an umbrella. Within 10 minutes, it is delivered by drone to your exact location. When the rain starts pouring a few minutes later, you are completely dry.”

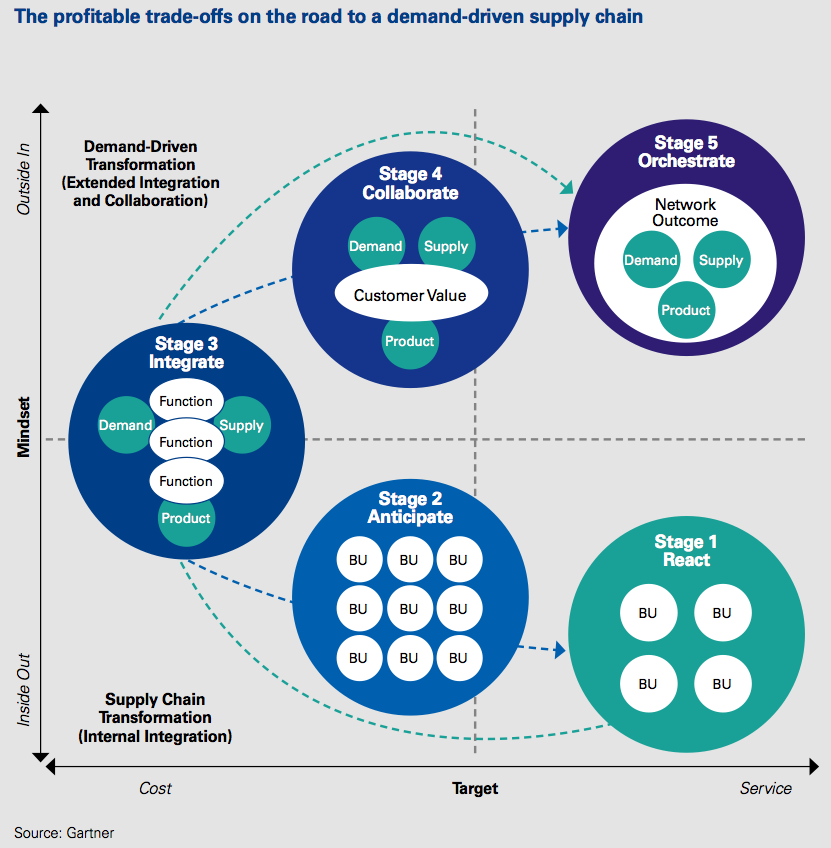

For Erich Gampenrieder, Head of KPMG’s Global Operations Center of Excellence, this is the perfect illustration of the concept known as ‘demand-driven supply chains’. In essence, the idea is as simple as it sounds: developing a supply chain in which planning, procurement and replenishment are aligned to consumption and consumer demand.

For the extremely satisfied customer at the bus stop, this meant keeping dry. For the company that delivered the umbrella, the rewards would be significant too. As Gampenrieder says: “Our research shows that companies with supply chains that are truly driven by demand can grow sales by 1-4%, cut operating costs by 5-10% and reduce inventory by 20-30%.” In a consumer market where margins are constantly under pressure, achieving those kind of gains could be transformative, but how do you get there? The traditional supply chain has served the industry well for a long time. A company could make a certain number of products for a certain cost in the confident expectation that, when they pushed them through the supply chain into stores, the margin on each item would be enough for them to make a profit. But the proposition at the heart of this model began to look obsolete as soon as globalization and the internet became commercial realities.

In today’s marketplace, consumers can shop anytime and anywhere, have unlimited information at their fingertips and are socially, ethically and environmentally aware. They are also empowered to express their opinion (and have the outlets to do so), are more exposed to risk and demand a personal experience. These major changes mean that businesses are discovering that the tried and tested models are no longer valid.

No typical transformation

Too often, the old supply chain model left companies with the wrong product, at the wrong place, time and cost. That is why, 10 years ago, Gartner Consulting came up with the concept of a five-stage journey to a demand-driven supply chain (see diagram opposite). The journey to the kind of umbrella-delivering perfection Gampenrieder has outlined isn’t short or straightforward and, partly because of that, companies often make basic mistakes when they first start out.

“No two supply chains are alike, so it’s very hard to copy another company successfully”

“You need to do the fundamental stuff before you take the next step. Because the concept of a demand-driven supply chain has only been with us for a decade, companies often misunderstand it. There’s always a supply chain initiative somewhere, which is said to be the best thing since sliced bread, so companies try that. And before they’ve had time to discover whether that worked, they read about another initiative that’s the best thing since sliced bread, so they try that too” says Gampenrieder.

Such haphazard approaches obscure the fact that, as he puts it, “There is no typical transformation journey. No two supply chains are alike, which makes it extremely hard for one company to just copy something another company has done and succeed.”

Cultural issues can compound the problem. Andrew Underwood, Supply Chain Partner at KPMG in the UK, says: “Many people who run supply chains are trained to just do what they’re told. Understanding consumer demand is usually driven by sales and marketing – and too often the supply chain just makes what they’re told to do work. This is especially true when it comes to new products. Essentially they are not able to sense-check what they are required to do, let alone do the analysis and explore whether it would be more profitable for the company to rationalize its SKUs when a new product is launched.”

Transformation, trust and trade-offs

The complexity of today’s supply chains doesn’t help matters. With more channels and partners, more countries to serve and, often, more outsourced manufacturers involved, this aspect of a company’s operations can be hard for other executives to fathom. “The increasing complexity of supply chains means that many companies who want to change don’t even know where to start,” says Underwood.Too many supply chain chiefs only get invited into the boardroom when something goes wrong and, as a consequence, the function is perceived as being only ever as good as the last bad event. This reinforces the view that supply chains are all about process, not policy, a mindset that makes it well-nigh impossible to design, create and execute a supply chain that does what it needs to do to satisfy consumers, drive growth and reduce costs.

“The supply chain strategy needs to be aligned to the company strategy”

Transformation starts with a thought, not a deed. “The supply chain strategy needs to be aligned to the company strategy,” says Gampenrieder. To do that, he says, you need to start with a mission statement – what are we trying to achieve? Then you have to understand the capabilities you need to fulfil your goal, agree the key performance indicators so you can be sure you’re on track, and define the financial cost to achieve the perfect order – the umbrella that arrives in such convenient, timely fashion. The executives in charge of supply chains have a responsibility too: “It is extremely important that they can quantify and describe the impact on the profit and loss statement in a one-page document, with easy graphs.”

The discussion required to achieve all this draws out some of the conflicts inherent in any company in the consumer marketplace. As Underwood suggests, sales will invariably want to sell everything to everybody everywhere and won’t lose much sleep over the expense of that – whereas for production, cost and utilization rates could be crucial.

Defining and aligning strategies should, Gampenrieder says, help companies answer one crucial question: “To know sooner and act faster, what do you need to be able to see? Do you have the visibility to know what your customers want and when and where they want it? Do you know where an order is at the moment, and can you quickly identify where demand and supply disconnect and understand any continuity issues before they occur?”

To deliver the strategy – and achieve this kind of visibility – companies need to collaborate so closely with suppliers and customers that they work as one virtual organization. Given that the relentless focus in supply chains for much of the past five years has been on ruthlessly eliminating cost, companies may need to build trust before they can truly collaborate with suppliers who may, at first, suspect a hidden, cost-driven agenda.

Yet if a virtual organization is created, companies can make informed, timely decisions across sales, marketing, finance, and operations. This will make it much easier to understand what the customer values and needs, develop plans that emphasize the cost to serve the customer and profitability, and identify the trade-offs that deliver the financial targets.

If you don’t have this, it will be harder to create a flexible, agile supply chain that meets customer demands and performs efficiently: managing risk and bottlenecks. The key is understanding – via custom-made scenarios – what trade-offs need to be made so that, for example, the company has a realistic idea of how expensive it will be to resolve an issue.

“The question many companies struggle to answer is: what do we need to change?” says Gampenrieder. “You can segment your supply chain by customer, product, region, sales channels – or combinations of the above – so you need to develop a few custom-made supply chain archetypes – no more than three to five, because the complexity will kill you. In this way you could, for example, analyze SKU management, identify those that don’t deliver the margin you need and free up capacity for those that do. Retailers could determine the cost to serve for a particular product or channel. The data on cost and performance could help them adjust the pricing model for particular delivery options or reconfigure inefficient processes at distribution centers such as packing and scanning.”

Many companies don’t make the most of such analysis because they lack the in-house expertise, don’t do these exercises often enough, and don’t know how to present the findings when they do. Instead of compelling dashboard-style visualizations, too many companies produce comprehensive, yet weighty, 120-page reports that will never be read by time-poor executives and will not, therefore, improve the company’s performance.

The trouble with transforming supply chains is that you can change anything and everything – but that doesn’t mean you ought to. “The momentum behind change can flounder if companies have too many priorities, aren’t focused, and don’t take initiatives in the right sequence,” Underwood says. “Understanding what to tackle first can be difficult – companies trying to implement advanced capabilities too soon can fail.” So, for example, firms turning to predictive analytics often realize that it’s hard to make the most of such innovations without investing in the supporting technology or core processes or restructuring some units.

Snakes and ladders

The danger is that if companies choose the wrong initiatives – or try to do too many at once without understanding how they interact – supply chain transformation turns into a corporate game of snakes and ladders, in which gains in one part of the organization are counterbalanced by losses elsewhere. “What we learn from early adopters is that different companies need different strategies because they are at different levels of maturity and have different supply chains,” says Gampenrieder.

Different companies have succeeded in varying ways. At Colgate, the focus of its transformation was return on assets and operating margin. At Procter & Gamble, it has been about saving money (in 2013, supply chain costs fell by US$1.6bn) while becoming more responsive. At Unilever, targeting the 3 Cs (customer service, carbon and costs) has led it to outsource less and in-source more.

Creating a demand-driven supply chain may not be quick, easy or cheap, but the companies that are succeeding have turned an aspect of their business that has historically been regarded chiefly as a cost center into something that can give them an enduring competitive advantage. With competition for consumers becoming ever fiercer, having the right product in the right place at the right time for the right price could be the key to growth for brands and retailers.

Informed decisions. Supply chains that function as one virtual organization have a better grasp of what customers value.

Harvesting China’s rural consumers

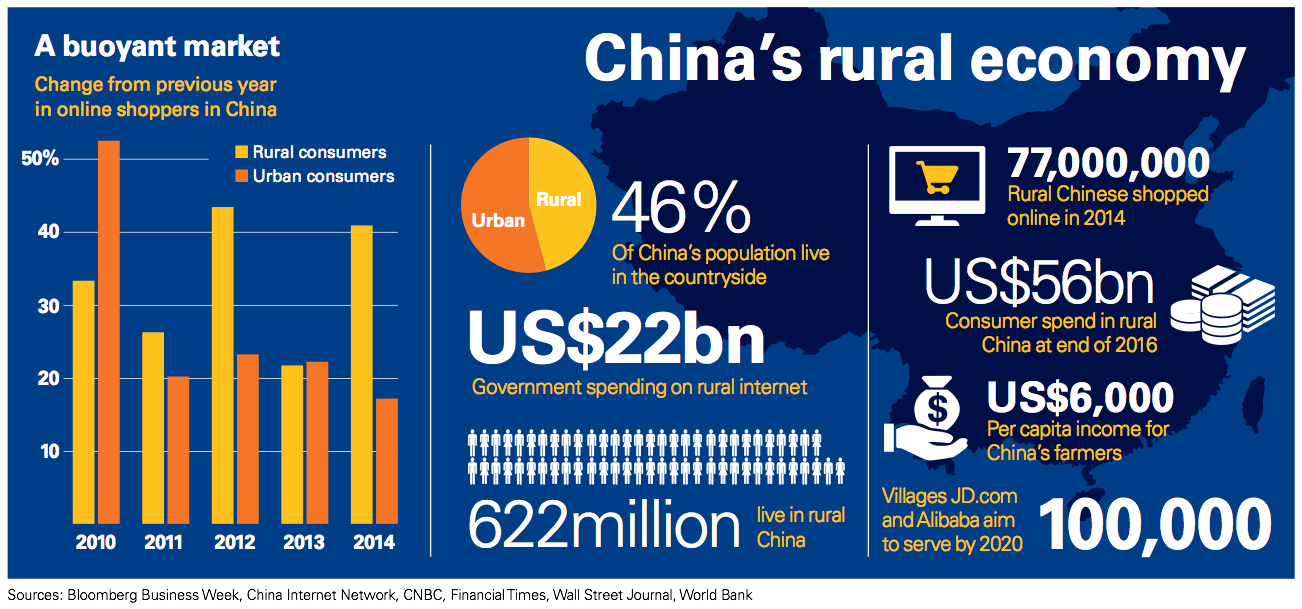

Look beyond China’s glamour cities into the countryside and you find a vibrant consumer market that could soon be worth US$56bn

You have probably heard that “May you live in interesting times” is a popular saying in China. It isn’t. That is one minor illustration of the outside world’s unerring ability to misunderstand China. Another example is the global obsession with its GDP growth. In the ‘new normal’, as analysts call it, the country’s economy is expected to grow by 6% a year between now and 2020. Yet, as the travel writer Peter Hessler noted, three things are never in short supply in China: change, tea and statistics. And if brands and retailers look beyond its largest cities, they will discover one of the world’s fastest growing consumer markets: rural China.

What kind of growth are we talking about here? Statistics from BGTimes Beijing suggest that shoppers in China’s rural areas spent around US$28bn in 2014, a sum they expect to virtually double to US$55.6bn by the end of 2016. “The new normal of 6% growth a year is still good,” says Jessie Qian, KPMG in China’s Head of Consumer Markets, “but that growth will vary across China. You will see smaller growth on the coast and faster growth in rural China, particularly in areas where the average annual income is US$2,000 or more, with a city whose population is a million or more nearby.” (The country has 96 cities each with a population of one to two million.)

Whatever the headlines, half-truths and generalizations, China’s consumer economy is in good shape. Chinese shoppers spent 10% more in the first half of 2015 than in the same period in 2014. As their disposable income rose by 8%, this means they are finally doing what the government has long wanted them to do – saving less and spending more. There is still a long way to go – consumption only accounts for 37% of GDP in China, compared to 60% in India and 70% in the US – but it’s a step in the right direction. Chinese consumers still have plenty to spend: JP Morgan estimates that they have more than US$9trn in the bank.

There is also a disconnect between perception and reality when it comes to rural China. The rise of the country’s megacities has obscured the fact that rural China is still home to 622 million people. In what you might call ‘trickle-across economics’, workers who have migrated to cities send around US$45bn a year home to relatives in the villages.

Emerging market. China’s rising rural middle class want the same luxuries as people living in cities

The unprecedented scale of this migration – an estimated 170 million workers return to their villages to celebrate New Year – could have unbalanced the country socially, financially and economically. Realizing this, China’s leaders have taken various steps – from improving infrastructure to giving farmers more freedom to manage their land and investing US$22bn to ensure that 98% of the countryside is connected to the internet by 2020 – to stimulate village economies. Poorer rural areas are benefitting from the government’s anti-poverty drive – the ambitious target is to eradicate it by 2020.

“Rural shoppers have more money and want to experience brands”

These initiatives are transforming China’s rural economy. A rural middle class has emerged, with disposable income and the confidence to spend it. The per capita income for farmers has reached US$6,000, a threshold that, in other parts of China, has seen consumer spending surge. By the end of 2014, there were 77 million rural online shoppers, 40% more than the year before. “Millions of people in rural areas are shopping on their smartphones,” says Li Fern Woo, Advisory Partner at KPMG in China. “And when they buy, they are likely to be influenced by social media, peer reviews and bloggers.”

China’s e-commerce giants are keen to seize the opportunity. JD.com is opening 500 shops in rural areas and striving to reach the farthest-flung areas with a network of 160 warehouses, 1,000 delivery stations and third-party alliances. In April 2015, Alibaba partnered with state-owned China Telecom to sell budget smartphones – some costing less than US$50 – in rural areas, with the shopping app for Alibaba pre-installed.

That is just one aspect of Alibaba’s audacious plan. It is investing US$1.6bn to build distribution hubs across the country and 100,000 drop-off locations in villages. At the heart of its strategy is the Taobao rural service center, where customers buy goods, pay mobile phone and utility bills, and collect items they have bought online from Taobao. The company provides computers and monitors, ensures timely delivery of purchases, and trains villagers to help run these centers, many of which are in convenience stores.

At first, Taobao sold such staple items as phones, washing machines, televisions, and apparel – but it could transform the rural economy in the long run. When it is confident that it has the talent and infrastructure in place, it plans to build a digital platform enabling farmers to sell their fruit and vegetables to the cities.

“In the past, the rural consumer has often been faced with limited choice of product and been offered low quality goods where price was the main attraction,” says Qian. “That is changing as consumers have more money, want to experience brands for the first time and look to buy products that improve the quality of their lives.” These shoppers still appreciate a bargain – the right price point is crucial – but are less willing to compromise on quality.

Reaching China’s flourishing but remote regions – and understanding the psychology of consumers in these communities – is far from straightforward. The government is easing restrictions on imports of foreign goods, but Unilever has decided to proceed with a local partner, Alibaba, using its distribution channels, Tmall B2C online marketplace and a unique QR code to verify the authenticity of its products. There are three fundamental causes for optimism about China’s rural consumers. President Xi’s government has turned words into deeds: changing policies, passing laws and making investments. China’s rural population has more disposable income – and hasn’t had access to many products and brands before. And if China’s ‘new normal’ is 6% annual growth in GDP, it may give a society that has condensed two centuries of economic development into 25 years the chance to enjoy living in uninteresting times.

Five key learnings

1. China’s consumer economy is holding up, which is why the country is still predicted to achieve 6% annual GDP growth. Chinese consumers are finally spending more, but there is plenty of room for expansion – as a percentage of GDP, China’s consumption is barely half that of the US.

2. China’s rural consumer economy is likely to boom because of rising disposable incomes and government policies to abolish poverty by 2020. Also, the emerging rural middle-class is acquiring a taste for quality products, choice and good customer service.

3. Chinese e-commerce giants are expanding into the countryside with a system of regional distribution centers. An online presence is essential as cheap mobile phones become widely available, with apps for Alibaba already installed.

4. Government restrictions on imports are being eased. The opportunity is being seized by foreign brands who are partnering with Alibaba to gain local knowledge. Don’t underestimate the complexity – regions are all different and logistics are still a challenge.

5. Be prepared to adapt. Rural consumers shop less frequently than their urban counterparts but spend more when they do. The rising rural middle class has its eye on the luxuries available in the cities and will require the same sophistication. (Jessie Qian, Partner, KPMG in China)

Clicks and bricks

Apparel brand Bonobos has made two seemingly opposing ideas about retail work together successfully

Eight years ago US company Bonobos was founded on the promise of better-fitting pants for men – to be sold exclusively online. “Most people would have said you can’t innovate in a mature category like men’s pants,” co-founder and CEO Andy Dunn tells ConsumerCurrents. “And even if you could, they would have said you can’t build a brand around a better fit without the capability for customers to try the clothes on.”

Bonobos proved the naysayers wrong: the company now describes itself as the largest apparel brand ever built online in the US. In its first full year of business, revenues were US$2m. In 2014, the Internet Retailer Top 500 guide estimated the firm’s e-commerce revenue had reached US$65m. The start-up’s success has helped make men’s apparel one of the fastest-growing online retail categories in the US, with sales up 17.4% in five years. The company believes its target audience – 18-34-year-old men – are especially keen to buy everything online.

Internet-driven model

Free shipping and no-hassle returns certainly helped Bonobos grow, but the pants had to look and feel good. Fashion-savvy magazines GQ and New York raved about the tailor-worthy fit – the pants have a patented curved waistband and an array of sizing options to accommodate every body type, banishing what some pundits have called the “saggy bottom” look. Bonobos’ flagship product, washed chinos, come in four styles, each offering 40 sizes and 15 colors. Instead of trying to save money by offering one cut to the widest possible group of men, the company allows shoppers to choose from 5,000 possible combinations of chinos.

“An Internet-driven model removes the hassle of assorting inventory to local stores and is the only way you can offer that kind of variety,” says Dunn, who believes the online store will continue to be the “main engine for disruption in retail. It will be the flagship store for every successful retailer by a factor of 10, and potentially 50 or 100 compared to their best-selling physical store.”

Bonobos was born out of a classroom project by Dunn’s best friend and roommate at Stanford Business School, Brian Spaly, who had been frustrated that most pants didn’t fit his athletic build. Graduating in 2007, he named the company after the bonobo, an endangered dwarf chimpanzee species, and appointed Dunn who, as CEO, helped raise millions in investment capital for the venture.

When Spaly departed by mutual agreement in 2009 (he later became founding CEO of men’s retailer Trunk Club, which was acquired by Nordstrom in 2014), it was left to Dunn to continue the business’s impressive growth. How has he done that? He has taken the e-tailer somewhere he thought he never would. He put Bonobos product into physical stores.

The company now has 20 bricks-and-mortar locations, in such major cities as Chicago, Houston, San Francisco and New York. Most of them have opened in the past two years. The company calls them ‘Guideshops,’ not stores, because there is no inventory for customers to walk out with, only to try on.

A ‘guide’ helps customers find the right fit and keys in their orders on the computer for home delivery a few days later. Customers who don’t buy anything are still emailed their sizes and a log of what they tried on. By the end of 2016, Bonobos plans to have 30 Guideshops in major urban centres and select smaller markets across the US.

Showrooms not stores

Many ecommerce revolutionaries regarded the bricks-and-mortar store as obsolete, and Dunn initially shared that assumption. “We said we would never be offline, and then, wait a second,” says Dunn. “We hit a big turning point. We realized offline really works.”

Bonobos discovered bricks-and-mortar can accelerate online sales and build customer affinity – just not in the traditional way.

“We said we’d never be offline, but hit a big turning point. We realized it really works”

It isn’t just strategy that has allowed Bonobos to convert men nervous about placing an order without a fitting – and to convince those who love the pants to try other apparel. The brand’s expansion into shirts and suits, using the same playbook of multiple silhouettes and deep sizing, only took off when they showcased them in Guideshops. Earlier this year, for the first time, sales of its shirts and suits were greater than pants.

Bonobos stumbled onto the Guideshops concept after opening fitting rooms in the lobby of its New York head office in 2011 when it was training a direct sales force. “We were hitting a million dollars in revenue right out of our lobby in 90 days,” says Dunn. “That was a lot of growth when our revenue was about US$15m.”

He says the company took away two lessons from the fitting rooms. “We realized that people still love to touch, feel and try on clothes, and nothing about the digital world is going to change that. But we also knew e-commerce had trained people to accept that the moment of purchase doesn’t have to be the moment of delivery,”he says. “The entire industry is built upon a false premise, which is there is some incredible joy that comes from the gratification of buying a product and immediately having it on-person.” For its typical customer – urban, mobile and time poor – taking their goods home is, if anything, a nuisance. “Now a guy can make a purchase – and continue on with his day without carrying it around,” says Dunn.

One of the key metrics Bonobos follows is its Net Promotor Score, an indicator of how likely customers are to recommend their experience to others. The score for its website is in the mid-70s, well above the industry average. The score for its Guideshops is consistently in the mid-80s. Dunn says this is because its sales people don’t have to manage inventory and can focus solely on providing attentive one-to-one service.

“The Guideshops are enhancing the consumer affinity with Bonobos, which is extremely difficult to do with in-person service,” says Dunn, who learned the pitfalls of traditional retail service as a student, when he worked as a salesperson at a famous upscale fashion brand. “We’ve made the job at retail about delivering great service and not about playing defense against inventory and customers all day.”

Because of the Guideshops’ relatively small size (average sq. ft: 1,000) and the fact the spaces are essentially showrooms, Dunn says the shops become profitable far quicker than traditional stores – typically within six months of opening. Encouraged by its bricks-and-mortar success, Bonobos formed a partnership to sell its pants in Nordstrom stores, where they’ve become the retailer’s top-selling chino.

The company is on its way to becoming a full menswear company with mass awareness. “We’ve come to realize physical retail isn’t going to compete with our online experience but fundamentally enhances this idea of better choice of fit and better customer service in menswear,” says Dunn. “We’re in no way declaring a victory on our business model yet – because we have more work to do – but we’ve been incredibly encouraged so far.”

The internet has allowed Bonobos’ CEO Andy Dunn to offer 5,000 possible variations of the company’s flagship product – washed chinos.

The rise of Bonobos

1.These pants don’t fit. Stanford Business School student – and self-taught amateur tailor – Brian Spaly decides the only way to get pants that fit him is to launch his own company.

2. What’s in a name? For reasons that may never be entirely clear, Spaly and new CEO Andy Dunn study a list of prospective names and choose ‘bonobos’ after a species of chimpanzee.

3. Wall Street invests. Dunn raises investment capital for Bonobos. Just as significantly, the company acquires a cult following among the city’s financiers after New York magazine hails them as “sexy-man pants.”

4. Training pays. Bonobos discovers the power of bricks and mortar when training a sales force at its head office – and changes its strategy, using compact ‘guideshops’ to diversify its products and attract new customers. In 2014, the company raises US$55m to finance the expansion of its American network of guideshops.

Value-driven

Flourishing in a flat market, Renault’s brand Dacia is a textbook example of reverse innovation

Reinventing a brand is one of the most complex tasks a company can undertake. To do so, while eliminating any risk of damage to the core brand, is trickier still.

Yet Renault has managed these twin challenges skillfully with Romanian car maker Dacia since it acquired the company in 1999.

Dacia – named after the Dacians, the country’s early habitants – was one of the industrial bastions of Romania’s Communist regime. Founded in 1966, the company dominated its home market but made little impact in the West, where cars from the Eastern bloc were regarded as cheap but unreliable. In the 1980s and 1990s, its core products were licenced versions of cars such as the Renault 12 and so, when the French automotive giant was looking to launch value-priced passenger vehicles in eastern Europe, Dacia was a logical acquisition.

The first thing Renault did was modernize the Dacia factory in Mioveni, as part of a €2bn (US$3bn) investment. Before the acquisition, the plant was making 85,500 cars with 26,500 workers. By 2014, it was producing 340,000 cars with 14,000 staff.

Vehicles produced by Dacia – primarily Logan, Duster and Sandero – are now so successful that they are sold by Renault and other brands in markets across the globe. The Logan, the 2004 entry-level model that was the first big launch for the revitalized Dacia, was conceived at Renault’s R&D HQ in France (though responsibility for R&D has since shifted to Romania.) Aiming for a target price of US$6,000, Renault took a stringent cost-to-design approach, using fewer parts than a typical Western car, offering a limited range of exterior color options, redesigning the windshield to reduce production and installation costs, and creating a vehicle that was easy to maintain.

The launch strategy focused on a product that could be scaled up or down to suit particular markets. In Germany, for example, it made the exterior more appealing with the use of metallic paint, enabling it to charge a higher price and improve its margins. In France, the Sandero model doesn’t have air conditioning, power locks or a radio as standard, but its listed price is US$10,560, significantly cheaper than comparable models from Škoda and Vauxhall/Opel. To suit emerging markets, the Logan has a fuel filter, higher ground clearance and a battery that survives extreme weather.

Dacia’s bosses had a clear picture of their prospective customers: people who bought a used car, a very small European vehicle or a cheap Asian import. For these car owners, space, reliability and price were paramount, so Dacia stressed how much space buyers got for their money and reassured them about quality with guarantees, frequent checks and satisfaction surveys. Its marketing strategy was different too. Initially eschewing TV advertising, Dacia developed a cool, no-hype vibe that suited a target audience motivated by value for money.

Renault’s investment in Dacia was considerable but, just in case the reinvention didn’t succeed, it introduced Dacia into new markets as a completely separate brand.

The strategy has clearly worked. The company’s price advantage has proved particularly effective in a European market bedevilled by recession, debt and unemployment, and where overall car sales have flatlined. In 2014, the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association’s figures show that Dacia’s sales soared by nearly 24% to 359,141 in the EU.

Established Western car makers have not found it easy to develop products for – and sell into – emerging markets. Dacia has proved that there is another way.

Jan-Benedict Steenkamp, professor of marketing at the Kenan-Flagler Business School in North Carolina, says: “Dacia is the best example of a car developed for emerging markets that has been introduced into developed markets and proved to be a real success. They were far ahead of other manufacturers.”