News Catastrophic Risk: Investing And Business Implications

- News

Catastrophic Risk: Investing And Business Implications

- IMAA

SHARE:

Featured

Investing in the Face of Catastrophic Risks: Strategic Business Insights

In this content piece, Professor Aswath Damodaran, a renowned finance professor at NYU’s Stern School of Business and a Valuation lecturer at IMAA, shared his insights on the complexities of valuing companies in the face of catastrophic risks. Drawing from various examples, including the volcanic threat to Iceland’s Blue Lagoon and a data breach at 23andMe, Damodaran emphasized how such catastrophic events can pose significant challenges to businesses, not just in terms of financial impact but also in how they are valued.

Damodaran explained that while traditional risk measures like volatility are useful, they often fall short in capturing the true nature of catastrophic risks, which can have devastating consequences for a company’s survival. He discussed the importance of understanding both continuous and discrete risks and how they affect a company’s valuation, noting that while some catastrophic risks are insurable, many are not, leading to complex valuation scenarios.

He also highlighted how markets often underprice or overprice companies based on perceived catastrophic risks, leading to potential misvaluation. Damodaran’s insights offer a nuanced perspective on how investors and businesses should approach valuation in uncertain and risk-laden environments, reinforcing the importance of incorporating a realistic assessment of catastrophic risks into valuation models.

Here are some of the key points Professor Damodaran put emphasis on:

- Although we often use statistical tools like volatility or correlation to quantify risk, it’s essential to recognize that risk extends beyond these numerical measures—it’s a more profound concept that isn’t purely abstract.

- Business owners may attempt to shield their companies from catastrophic risks, but such protective measures may not always be available, and even when they are, they might not offer full coverage.

- Implementing measures to enhance adaptability and protect against catastrophic risks is only justifiable when the benefits outweigh the associated costs.

Read the full insights written by Professor Damodaran here: https://seekingalpha.com/article/4671134-catastrophic-risk-investing-business-implications

In the context of valuing companies, and sharing those valuations, I do get suggestions from readers on companies that I should value next. While I don’t have the time or the bandwidth to value all of the suggested companies, a reader from Iceland, a couple of weeks ago, made a suggestion on a company to value that I found intriguing. He suggested Blue Lagoon, a well-regarded Icelandic Spa with a history of profitability, that was finding its existence under threat, as a result of volcanic activity in Southwest Iceland. In another story that made the rounds in recent weeks, 23andMe (ME), a genetic testing company that offers its customers genetic and health information, based upon saliva sample, found itself facing the brink, after a hacker claimed to have hacked the site and accessed the genetic information of millions of its customers. Stepping back a bit, one claim that climate change advocates have made not just about fossil fuel companies, but about all businesses, is that investors are underestimating the effects that climate change will have on economic systems and on value. These are three very different stories, but what they share in common is a fear, imminent or expected, of a catastrophic event that may put a company’s business at risk.

Deconstructing Risk

While we may use statistical measures like volatility or correlation to measure risk in practice, risk is not a statistical abstraction. Its impact is not just financial, but emotional and physical, and it predates markets. The risks that our ancestors faced, in the early stages of humanity, were physical, coming from natural disasters and predators, and physical risks remained the dominant form of risk that humans were exposed to, almost until the Middle Ages. In fact, the separation of risk into physical and financial risk took form just a few hundred years ago, when trade between Europe and Asia required ships to survive storms, disease and pirates to make it to their destinations; shipowners, ensconced in London and Lisbon, bore the financial risk, but the sailors bore the physical risk. It is no coincidence that the insurance business, as we know it, traces its history back to those days as well.

I have no particular insights to offer on physical risk, other than to note that while taking on physical risks for some has become a leisure activity; I have no desire to climb Mount Everest or jump out of an aircraft. Much of the risk that I think about is related to risks that businesses face, how that risk affects their decision-making and how much it affects their value. If you start enumerating every risk a business is exposed to, you will find yourself being overwhelmed by that list, and it is for that reason that I categorize risk into the groupings that I described in an earlier post on risk. I want to focus in this post on the third distinction I drew on risk, where I grouped risk into discrete risk and continuous risk, with the latter affecting businesses all the time and the former showing up infrequently, but often having much larger impact. Another, albeit closely related, distinction is between incremental risk, i.e., risk that can change earnings, growth, and thus value, by material amounts, and catastrophic risk, which is risk that can put a company’s survival at risk, or alter its trajectory dramatically.

There are a multitude of factors that can give rise to catastrophic risk, and it is worth highlighting them and examining the variations that you will observe across different catastrophic risks. Put simply, a volcanic eruption, a global pandemic, a hack of a company’s database and the death of a key CEO are all catastrophic events, but they differ on three dimensions:

- Source: I started this post with a mention of a volcano eruption in Iceland put an Icelandic business at risk, and natural disasters can still be a major factor determining the success or failure of businesses. It is true that there are insurance products available to protect against some of these risks, at least in some parts of the world, and that may allow companies in Florida (California) to live through the risks from hurricanes (earthquakes), albeit at a cost. Human beings add to nature’s catastrophes with wars and terrorism wreaking havoc not just on human lives, but also on businesses that are in their crosshairs. As I noted in my post on country risk, it is difficult, and sometimes impossible, to build and preserve a business, when you operate in a part of the world where violence surrounds you. In some cases, a change in regulatory or tax law can put the business model for a company or many companies at risk. I confess that the line between whether nature or man is to blame for some catastrophes is a gray one and to illustrate, consider the COVID crisis in 2020. Even if you believe you know the origins of COVID (a lab leak or a natural zoonotic spillover), it is undeniable that the choices made by governments and people exacerbated its consequences.

- Locus of Damage: Some catastrophes created limited damage, perhaps isolated to a single business, but others can create damage that extends across a sector geographies or the entire economy. The reason that the volcano eruptions in Iceland are not creating market tremors is because the damage is likely to be isolated to the businesses, like Blue Lagoon, in the path of the lava, and more generally to Iceland, an astonishingly beautiful country, but one with a small economic footprint. An earthquake in California will affect a far bigger swath of companies, partly because the state is home to the fifth largest economy in the world, and the pandemic in 2020 caused an economic shutdown that had consequences across all business, and was catastrophic for the hospitality and travel businesses.

- Likelihood: There is a third dimension on which catastrophic risks can vary, and that is in terms of likelihood of occurrence. Most catastrophic risks are low-probability events, but those low probabilities can become high likelihood events, with the passage of time. Going back to the stories that I started this post with, Iceland has always had volcanos, as have other parts of the world, and until recently, the likelihood that those volcanos would become active was low. In a similar vein, pandemics have always been with us, with a history of wreaking havoc, but in the last few decades, with the advance of medical science, we assumed that they would stay contained. In both cases, the probabilities shifted dramatically, and with it, the expected consequences.

Business owners can try to insulate themselves from catastrophic risk, but as we will see in the next sections, those protections may not exist, and even if they do, they may not be complete. In fact, as the probabilities of catastrophic risk increases, it will become more and more difficult to protect yourself against the risk.

Dealing with catastrophic risk

It is undeniable that catastrophic risk affects the values of businesses, and their market pricing, and it is worth examining how it plays out in each domain. I will start this section with what, at least for me, I am familiar ground, and look at how to incorporate the presence of catastrophic risk, when valuing businesses and markets. I will close the section by looking at the equally interesting question of how markets price catastrophic risk, and why pricing and value can diverge (again).

Catastrophic Risk and Intrinsic Value

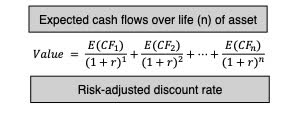

Much as we like to dress up intrinsic value with models and inputs, the truth is that intrinsic valuation at its core is built around a simple proposition: The value of an asset or business is the present value of the expected cash flows on it:

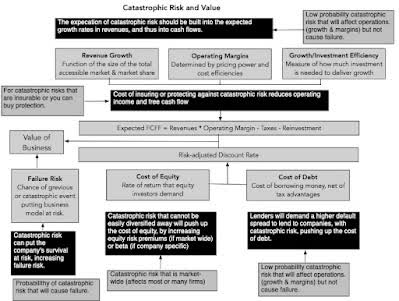

That equation gives rise to what I term the “It Proposition”, which is that for “it” to have value, “it” has to affect either the expected cashflows or the risk of an asset or business. This simplistic proposition has served me well when looking at everything from the value of intangibles, as you can see in this post that I had on Birkenstock, to the emptiness at the heart of the claim that ESG is good for value, in this post. Using that framework to analyze catastrophic risk, in all of its forms, its effects can show in almost every input into intrinsic value:

Looking at this picture, your first reaction might be confusion, since the practical question you will face when you value Blue Lagoon, in the face of a volcanic eruption, and 23andMe, after a data hack, is which of the different paths to incorporating catastrophic risks into value you should adopt. To address this, I created a flowchart that looks at catastrophic risk on two dimensions, with the first built around whether you can buy insurance or protection that insulates the company against its impact and the other around whether it is risk that is specific to a business or one that can spill over and affect many businesses.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Heading 2

Heading 3

Heading 4

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter