Publications People Integration: Capturing M&A Value By Making The Most Of Human Capital Post Deal

- Publications

People Integration: Capturing M&A Value By Making The Most Of Human Capital Post Deal

- Bea

SHARE:

At a glance

The people aspects of integration cannot be handled in a silo away from the rest of the effort. Human capital issues are critical to every work stream.

Successful merger integration involves detailed planning and execution when assessing leaders, designing the organization, retaining the right people, aligning cultures, communicating effectively, and more.

Effective change management is key to integrating people with business strategy. It increases confidence in direction and outcomes, accelerates results and sustains change benefits.

Introduction

You’ve decided to make an acquisition. You’ve done your homework and found the right company with the right strategic fit. You’ve completed your diligence reviews and examined the numbers from every angle and then some. You’ve considered all of the likely market reactions. In short, you’re convinced that this deal represents an excellent opportunity to create shareholder value.

But you also know it won’t be an easy road.

You suspect the two corporate cultures might not mesh as tightly as you’d like. You already know there will be extensive job overlap, and your people know it too. You fear that the best-and- the-brightest at both companies may already be headed for the exits.

In short, you anticipate more than a few challenges during the all- important integration of work practices, decision-making styles, human resources (HR) policies and processes, and organizational reporting relationships. Indeed, the very strategic rationale for the deal may involve having to adopt an entirely different operating model—for both your existing employees and the incoming workforce.

So, what’s a proactive leader to do?

Perhaps your best chances for success lie in (1) bringing the combined organization together around a single company culture, (2) finding the right incentives for retaining the people you need for both the transition and the longer-term, (3) adding some quick clarity to your organization’s structure, and (4) adopting an approach to selection and staffing that is perceived as both fair and transparent. How you address those people issues—and when—will prove critical to beating the odds stacked against deal success.

Most report unfavorable results after deals

Companies are experiencing less than desirable results in many areas of critical post-close performance. For example, according to the results of a PwC survey of M&A integration practices and outcomes, only 36% of finance executives report “very favorable” results when

it comes to improvement in profitability and cash flow following the deal, and only 30% report very favorable reports regarding employees’ understanding of the company’s direction. Favorable results were least likely to be achieved in the areas of employee retention, energy and enthusiasm, and morale (all at 23%), speed of decision making (21%), productivity (16%), and speed to market (14%).

The issues our clients face and the actions we help them take

A critical requirement of any successful Merger and Acquisitions (M&A) transaction is to put the fundamentals of the integration effort in place as early and as quickly as possible during the deal process. Your future ability to minimize business disruptions and achieve synergies just might depend on it.

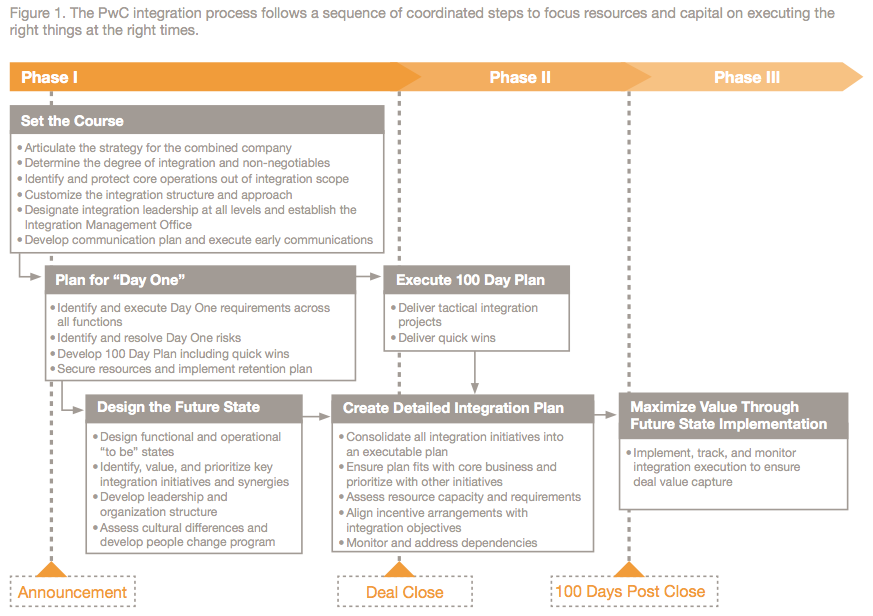

At PwC, we’re often asked to help support clients by rapidly launching integration efforts to “Set the Course”, “Plan for and execute Day One”, and “Design and maximize future state operations” — the three core components of any integration effort. Contained within those core components are all of the many decisions that must be made and tasks that must be completed if a company hopes to improve its chances of achieving a successful integration.

Like the name suggests, to set the course of an integration involves establishing the direction for its future rollout in light of the strategic focus that is behind the transaction itself. To plan for and execute Day One involves (1) planning all the activities that will make for a smooth operational transition post close and (2) actually carrying them out. Likewise, to design and maximize the future state operations is to ensure the transformational vision for the future organization in fact gets achieved.

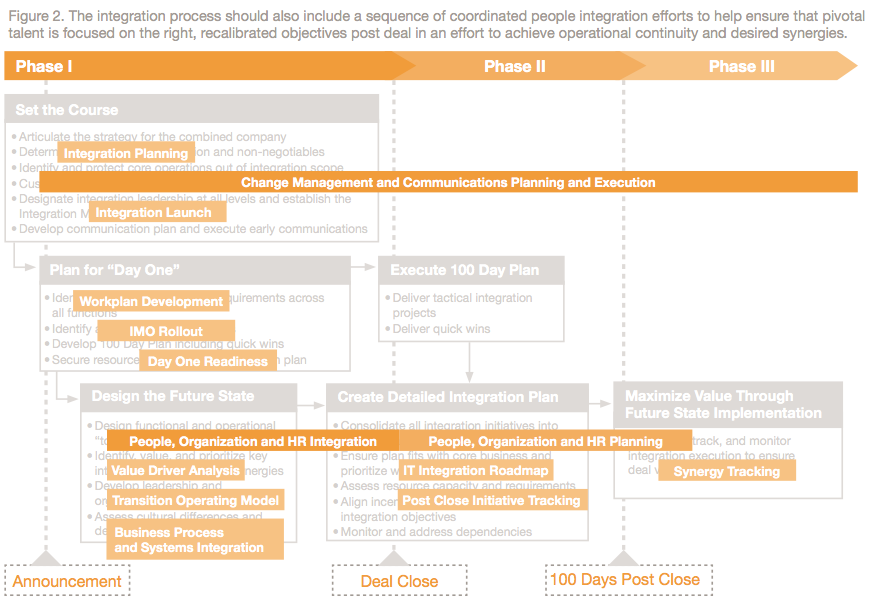

Figure 1 illustrates the tiered and phased approach PwC follows when helping a client manage a merger integration as an enterprise-wide business process across multiple functional areas. Figure 2 illustrates the various people integration activities that should accompany the overall integration process and how they fit into the larger effort.

It’s important to emphasize that the people aspects of integration cannot be dealt with in a silo that’s separate and disconnected from the rest of the effort. Instead, issues related to human capital and performance are inherent in—and critical to—every work stream. Those issues involve responding to questions such as: Have people from both sides accepted the rationale for the deal? Do they possess the skills necessary for the integrated organization to prosper over the longer term? Is the right talent being deployed in the right positions and will people be required to learn new systems, processes, and skills to do their jobs?

Unquestionably, effective merger integration involves detailed planning and efficient execution across a wide-range of HR-related work streams, including:

• HR confirmatory due diligence: Collecting the people-related policies, plans and data needed to integrate the HR operations of the two organizations

• Leadership assessment: Assessing the qualifications and competencies of top leaders at both companies to determine their role in the new combined organization

• Employee retention: Determining the skills, knowledge and abilities critical for future success, identifying the people in both organizations who possess those competencies, and developing a retention plan to persuade them to stay

• Culture: Analyzing the cultural compatibilities and differences between both companies, understanding the cultural attributes critical to shared success, aligning existing cultural attributes with future need, and creating a roadmap to quick wins and longer-term culture building

Setting the course empowers an integration team to define the road ahead with actionable tasks—and authorizes them to see to it that those tasks get carried out.

• Organization design: Identifying the strategic and tactical criteria for the design of the combined organization while establishing new structures and reporting relationships

• Communication: Recognizing the needs of the various internal stakeholders and developing the targeted key messages and milestones from announcement though Day One and beyond

• Staffing and selection: Understanding the talent requirements of the new organization and implementing an effective selection process in place to match the right people with the right positions

• HR policy and practice: Comparing the similarities and differences between the HR policies, plans and practices currently in place across the two companies

• Performance and rewards: Establishing a comparable and competitive platform of employee rewards built upon a clear set of meaningful performance metrics

• HRIS: Integrating the two companies’ human resource information systems (HRIS)

• On-boarding: Preparing the employees of the target company to begin work at the acquirer, recognizing that the on-boarding process following a merger is generally significantly different from the regular process for a new hire

• Training: Delivering critical training to sales and customer-facing staff on new products and processes

While each of the aforementioned issues is important to address, some will take priority over others based on the unique issues and circumstances of each transaction. In this paper we cover some of the most critical aspects of the people integration process, focusing on the issues PwC views as most critical to success—issues like leadership assessment, employee retention, organization design, cultural integration, staffing and selection, and HR policy and practice.

Set the course

A merger or acquisition, like other large-scale enterprise-wide change, is an excellent opportunity to set a new course—both operationally and across the various support functions of the newly combined business.

Among other things, to “Set the Course” involves the establishment of clear leadership, new organizational structure and role clarity, a reasoned approach to employee retention, and an achievable, concrete plan in the form of a roadmap for making the transition to the next stage in the organization’s growth. Setting the course empowers members of the integration team to define the road ahead with actionable tasks—and authorizes them to see to it that those tasks get carried out.

Assessing executive leadership

One of the most important aspects of setting the course involves determining the parties who will be establishing the blueprint. Specifically, decisions must be made regarding which senior leaders from the combining organizations will assume which leadership roles, both during the integration effort and longer-term.

At this stage, leadership tends to fall into one of two categories.

• Leading the integration effort itself. Establishing leadership for the short-term to mid-term integration effort often falls to the acquirer prior to close. Assembling an effective integration leadership team is a critical prerequisite to achieving strategic goals and synergy targets. Key leaders often make up the integration steering committee.

• Setting the course and leading the newly combined organization. Setting forth the true blueprint for the future is often done by the acquirer prior to close, but the target is sometimes given a significant role in shaping and executing it.

Successful integrators begin by sizing up senior managers and key specialists early in the diligence and pre-close integration-planning processes. That way, once the deal closes and access is unfettered, the acquirer can quickly conduct a more comprehensive evaluation of the target management’s leadership and technical capabilities.

Once the future of the target’s CEO has been determined—typically during the pre-close transition planning period—a strong sense of the second tier of leadership almost invariably emerges as the acquirer gets to interact with the target’s executives and informally compares their capabilities with those of its own executives. Later, a more formal assessment lends objectivity and credibility to the decision-making process.

Equally as important, the performance of executives from both sides during the pre-close integration planning process can provide some vital clues. And while it’s only natural for executives competing for a limited number of leadership posts to try to prove themselves, lots of one-upmanship and behaviors that undermine the contribution of others is often not the best indicator of future leadership potential.

Important indicators of an executive’s leadership potential include: the ability to deliver against milestones with speed and a sense of urgency; the ability to work collaboratively with others from both sides of the transaction; the ability to advocate on behalf of the best candidate for a role, regardless of the candidate’s legacy organization; an ability to anticipate issues and recommend ways forward that align with the underlying rationale for the deal; and the ability to manage critical resources between business-as-usual activities and the integration effort.

Below the executive level, a formal assessment of leadership potential for the third and fourth tiers of leadership is highly recommended, including the review of past accomplishments and the relevance of a candidate’s skills, knowledge sets, and career goals to an organization’s future success. And, of course, what future success will ultimately look like must be defined by the company’s strategy for the future, not what has passed for success in the past.

Not surprisingly, it is sometimes difficult for managers at one company to be objective in assessing their counterparts at another. That’s why there must be either (1) an objective, independent process involving leaders from both organizations or (2) a structured assessment procedure administered by a third party. In fact, some companies turn to external advisors to uniformly apply a standardized process for examining the competencies of the leading contenders for each job. That way executives from both organizations can be independently assessed relative to the future needs of the organization.

This process can have a positive impact on post-close productivity and retention, reassuring target management that the acquirer is committed to being fair and reasonable, while injecting a sense of perspective and objectivity into the acquirer’s own managers — thereby reinforcing the importance of continued performance.

Setting organization structure and defining role clarity

It is a widely accepted theory of merger integration that little of permanence can get done following a deal until the organizational structure has been set. Fear, indecision, and just plain confusion often paralyze the new organization until people have some sense of where—and even whether— they fit within the new environment, and what will be expected of them.

It’s only natural that people would want to know what’s expected of them, what they’re accountable for, and what decisions they own. You can’t expect effective execution of an integration effort until (1) you can publish the accountability (i.e., answerability for end results) and decision-making authority for each position on the organizational chart, and (2) you can define the ways the structure will create sustained economic value.

That said, while decisions about organizational structure and job role can’t be fully executed until after the transaction closes, smart acquirers can still begin planning the shape of the combined company well in advance of Day One.

CEOs seldom experience more pressure to clarify authority, control and reporting relationships than after the announcement of a deal. The mixing together of two already well-formed organizations can cause anxiety, ambiguity, and confusion among those in both organizations. Senior leadership must make critical decisions about organizational design and reporting structure.

Unfortunately, leadership sometimes succumbs to pressure and decisions often favor form over function, title over accountability, and hierarchy over role clarity.

The first symptoms appear during the horse trading and hurried negotiating that typically accompany the early stages of a transition. The result often leads to competitive group behaviors and early preoccupation with organizational charts. In a misguided attempt to balance the bartering at the executive level, mid-level and lower- level managers are often placed into inappropriate jobs.

Traditional organizational charts often communicate more about authority, status, power, and turf than about how information should flow and how decisions should be made. Clearly, everyone needs to know whom they report to. But knowing reporting relationships does not alone ensure alignment, productivity, timely decision-making, and high performance.

Rather, high performance is a byproduct of organizational clarity—clarity about how a person influences end results and what that person’s role is in relationship to the roles of others. Until individual roles relative to core processes have been addressed, the only value an organizational chart has is the superficial sense of control it gives senior leaders.

People want to know what is expected of them, what they’re accountable for, and what decisions they own. You cannot expect effective execution until you can publish on the chart the accountability and decision authority for each position and define how the structure will create sustained economic value.

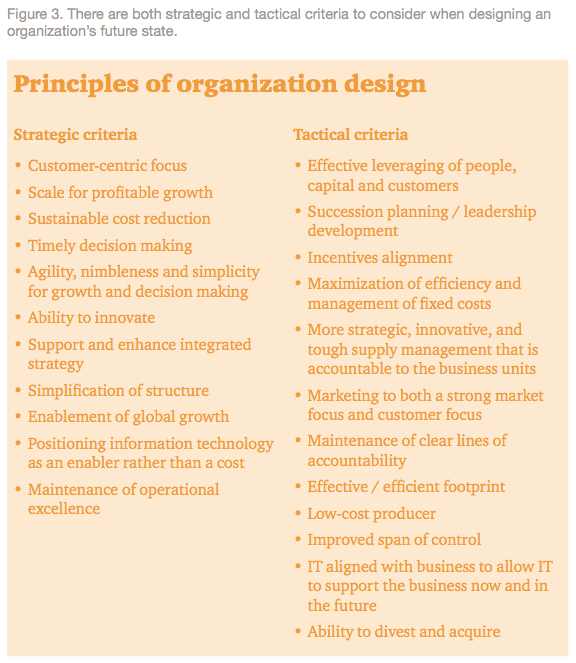

Acquirers should start designing the future state early in the deal process. The economic value drivers behind the deal in the first place should permeate the entire integration effort by setting the parameters and the target end state for the organizational design. Once you’ve confirmed the strategic objective, you should (1) set the design principles by applying both strategic and tactical criteria, (2) develop an interim organizational structure, and (3) agree upon a future state to be realized approximately 12 months post close. Only then, after completion of all the preliminary work, should you even start to put names in boxes. Do resist, by all means, the temptation to begin the process where it should end—by attaching names to specific roles.

Getting the design right is an important prerequisite for an effective talent retention, selection, and staffing process. It defines the staff hierarchy and the job design as necessary inputs to a fair and effective talent selection process.

Keeping the people you need to keep

Many acquiring companies pay significant retention bonuses. But all too often they spend money on retention programs without linking the reward to integration goals.

Once the people most vital to ongoing operations have been identified, several considerations should be assessed when developing the terms of the retention program. These include:

• Criticality. Before a company can direct financial incentives to key people, it first needs to define their relative importance to the business—both during the transition and beyond. For example, some individuals may be integral to facilitating an orderly transition of the target’s customer-base to the acquirer, while others may be integral to managing—or otherwise maintaining—the target’s ongoing operations. Still others may be critical simply because no one else is doing, or can do, their job.

The levels of “criticality” can be described as follows:

Strategically critical —Those most essential to the ongoing operations of the new combined organization

Integration critical —Those most essential to the merger integration effort

Knowledge transfer critical —Those most essential to the transfer of ongoing specialized knowledge

The financial (and other) incentives that comprise the retention award will vary based on the talent objectives for staff at each level of criticality and their specific retention time horizon.

The exercise of categorizing staff by their level of criticality forces a company to evaluate employees individually and determine whether it will need different retention packages for managers at different levels or locations. It also makes it easier to re-deploy strong performers to other positions within the new organization, especially when two solid employees perform similar roles.

• Retention period. Knowing how long you want key employees to stay (i.e. their “retention time horizon”) and understanding what might be motivating them to go, are prerequisites for designing effective retention packages. While you may want to keep some employees indefinitely, others may only be needed for a limited time.

• Status post retention. Assessing long-term staffing needs can help determine which employees currently receiving a retention package will be terminated when the retention period ends. This, in turn, will help to coordinate retention payments and severance awards to avoid duplicative payments to those being terminated. Sometimes the very prospect of receiving a severance award upon termination—after the close of the initial severance period—may encourage those receiving retention packages to stay beyond the expiration of the retention period rather than seek employment elsewhere.

After evaluating these factors for each key employee or group, successful companies also account for the following in designing retention programs.

• Award size.The ideal retention payment should be big enough— from an employee’s perspective —to make staying-on worthwhile, but still affordable and justifiable for the acquirer. The target award can be a percentage of base salary, a flat dollar amount, or an amount that increases over time as retention and integration milestones are met. Awards should be based on comparative benchmarking data and market practice.

• Award type. A retention payment is typically paid in cash or equity, or some combination of the two. Most often, the type of the award used is driven by the criticality and retention time horizon of the person being retained. Strategically-critical talent is often offered a mix of different types of equity reflecting the longer-term investment in the business expected of such talent. Equity awards range from stock options and restricted stock units to outright grants of actual shares that must be held for a specific time period. The shares, options and units awarded typically vest gradually to the recipient over a period of years, reflecting competitive practice for equity awards.

• Integration critical employees very often receive cash awards that are paid upon deal close or the completion of a set period post close. The awards are usually pro-rated if the employee is terminated earlier. Knowledge critical employees receive similar awards, but the payout often requires a longer period of service after close.

• Funding. Retention packages can be immediately funded when earned or paid from a performance-based pool whose size varies with the achievement of specific performance goals such as the timely achievement of integration milestones. Many performance-based retention programs use a “sliding scale” that pays a base amount at a threshold level of performance, a larger award when the performance target is met, and a performance premium (often capped) for exceeding the target.

• Payment timing. The date for receiving the payment(s) should be realistic from the employee’s perspective. Avoid setting an award date too far in the future. If the goal is to retain certain employees for extended periods of time, consider paying the award in installments over the retention period, or back-loading the payments so that more of it is paid at the end of the period. Earnouts—that is, retention plans that reward participants for meeting specific performance objectives in a set amount of time are often used as incentives for entrepreneurs and principal owners. For all practical purposes, some longer-term retention programs simply blend with regular pay-for-performance programs over time.

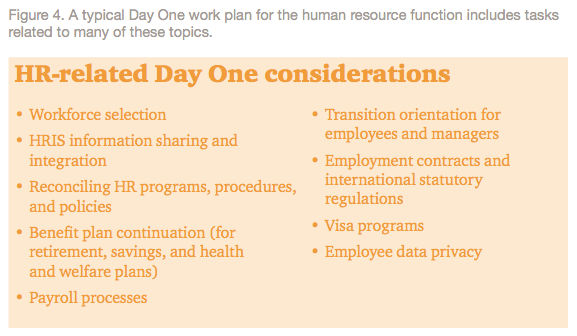

Day One is about continuity. And this is never truer than with people matters because there are customers to be served, payrolls to be met, employee benefit coverages to be extended, and workplace infrastructure to be maintained.

It is also important to consider the use of “soft”, non-monetary incentives like independence and influence when success hinges on retaining entrepreneurs or those skilled in emerging technologies. Creating an organizational framework that allows such employees to operate more independently and autonomously, while maintaining an appropriate degree of oversight, may be the best way to get value from these individuals.

Plan for and execute Day One

Even if you make the very best decisions as you “Set the course”, much can go wrong at close absent proper planning and execution. While Day One can be a milestone for celebration, it is also the time for smooth transition of mission-critical operations. After all, normal work doesn’t stop when a deal closes. If anything there’s more to be done than ever.

Day One is about continuity. And this is never truer than with people matters because there are customers to be served, payrolls to be met, employee benefit coverages to be extended, and workplace infrastructure to be maintained—in the form of assets, systems, and processes that allow people to do their jobs day to day.

Critical Day One tasks need to be identified early, before longer-term, more-detailed planning commences. This allows for prompt identification of long lead-time items, well before they can turn into closing-day surprises. A detailed plan should then be created that includes all of the actions that will be put in place on Day One. Planning for Day One should begin in conjunction with the due diligence process.

Staffing and selection: Fitting the right people into the right roles

There’s an old proverb that goes: “If you see a turtle on a fence post, you know someone put it there.”

In the world of mergers and acquisitions, the same can often be said of people in senior positions who didn’t secure their posts on their own merit. The long-term result of perpetuating such arbitrary staffing decisions can be the wrong people in the wrong jobs for years to come following a deal.

Of course, that isn’t always the case. Remember: we’re generalizing here, and the way things work out in reality are often more complicated than a company might expect. In fact, the results of staffing decisions are often less about how they got made and more about (1) whether those ultimately chosen are in fact capable in the role or not, and (2) whether their skills and experiences are relevant to the organization’s future or not. That said, poor selection processes often lead to poor staffing decisions.

Of course fitting the right people into the right roles is never easy. It takes time, discipline, and selection practices that are comprehensive, yet relatively straightforward to implement. At a minimum, it requires:

• Clarifying the core competencies and skills required for key jobs. Workforce plans must clearly articulate job requirements. This requires knowledge of which jobs will change as a result of the integration and how they will change. Employers must create job descriptions that adequately define each position.

• Identifying skill gaps. Skill gaps should be identified and prioritized as soon as possible once the new organization design is available. The workforce must be sufficiently skilled to adjust to resulting systems and process changes.

• Matching job levels. Properly matching job levels between the two companies should begin as soon as possible after close.

• Tailoring the assessment and selection process to deal timing. Selection of talent can be staged throughout the integration process: Leadership and top management positions are filled during the early stages leading up to Day One or shortly thereafter. Layering the selection by management levels enables the company to simultaneously make strategic selection decisions and build its organizational design.

• Providing needed job training. Training may be needed to support core transitional requirements where new systems or processes are introduced. Pre-close training can be fundamental to ensuring the uninterrupted delivery of services on Day One regardless of whether the employee operates in the field, in a call center, or in the corporate headquarters. At a minimum, training should address things like how to answer the phones, impact on customer bills, specifics of the newly combined product and services offerings, and how to process new customer orders.

Only by following the right talent assessment and selection process can a company ensure that the right people with the right skills fill the proper roles.

As discussed earlier, it’s one thing to decide which leaders, managers and specialists are critical to the new operation; keeping them on board is quite another. It can be a huge challenge, especially when entrepreneurial executives stand to benefit from a substantial payday at close, while others are at risk of losing their jobs. Employee-retention planning typically takes place ahead of close, with program awards being communicated shortly after Day One. That said, retention awards for key talent are often communicated prior to close.

HR policies, plans and practices

According to the PricewaterhouseCoopers 11th Annual CEO Survey, “people agenda” was one of the top priorities for organizations, with 58% of CEOs saying that is one of their top priorities. However, much fewer—only 14%—report strongly agreeing that senior management spends adequate time on people issues during times of strategic change.

One of the most overlooked advantages of a deal is the opportunity to overhaul outdated people-related policies, plans and practices. Performing such an overhaul better aligns employees with business priorities. A merger or acquisition provides a temporary shield for altering structure, redeploying people, redesigning roles, and reconfiguring people processes and systems.

Unfortunately, the chance to eliminate policies and practices that constrain and obstruct performance often gets lost in a narrowly focused, post-deal rush to simply reduce costs. That happens when management teams begin cutting costs before fixing—or even understanding—the processes and systems that drive the costs. This phenomenon is driven by the belief that any—often significant— acquisition premium paid will be justified by synergy-related cost cutting. In fact, such cost cutting results only in the inadvertant elimination of organizational capacity and capability.

Employees better understand how to focus their efforts when operating policies are integrated within the first 100 Days post close. Quickly integrating operating policies helps solidify an awareness of a company’s new direction which, in turn, better positions employees to help the company succeed by focusing their efforts on the things that matter most. In a PwC-conducted survey, a full 38% of respondents said they achieved favorable results with regard to a “clear understanding of company direction” if the operating policies of the two organizations were integrated within three months or less post close. When the integration took four to six months or more, that figure dropped to 70%.

When decisions are made to integrate the companies’ people- related policies and practices, they’re often based on which company’s practices are seen as best at the time. The risk of this approach is that one company’s best practices typically work best in the specific circumstances that exist at any given moment. But those circumstances change on the heels of a deal, so the conditions that made certain policies or practices ideal before the deal may not support preservation of the status quo after the deal.

Each organization enters a merger or an acquisition as a fully functioning, self-contained systems of processes and practices. Selectively swapping out a practice from one organization and substituting one from the other can disrupt systems and processes in ways that are difficult to anticipate and more difficult to correct.

Design and maximize future state operations

If the findings of survey after survey are to be believed, concern over culture clash is identified as the leading cause of nearly half of all integration failures.

While many leaders worry about issues of cultural incompatibility and alignments, such issues, though, all too often get short-changed by lack of focus early in the deal or integration process.

Assessing (and transforming) corporate culture

Corporate culture is that set of entrenched behaviors that characterize how a company gets things done. Cultural differences between companies—in operating style, in the handling of customer relations, in methods of decision making, collaboration, and communication – can become major obstacles to achieving the strategic and operational goals of a merger or acquisition.

It’s a huge leap, however, to claim that those differences alone are the primary reasons behind the less-than-optimal performance of a newly combined company. Our research suggests that the culprit isn’t solely cultural conflict. Rather, lack of focus on value-driving actions and failure to generate early momentum can also significantly affect capture of deal value.

Cultural alignment is a deliberate, planned management activity that plays a critical role in nearly all M&A integration environments. Managers face certain challenges in their efforts to align two company cultures. Sometimes the challenge lies not in the cultures themselves, but in the managers’ inability to perceive a culture. That is, managers may not understand how it functions across the two organizations and how to manage it to drive economic value.

Performing a cultural assessment can identify dominant operating styles and entrenched behaviors within each organization. Identifying and mapping the differences between the operating styles, cultural drivers, and HR policies and practices of the two companies can give the acquirer a clear sense of the extent of the gulf between the two organizations and may help to defuse any cultural “roadblocks” that impede integration progress.

Changes in organizational culture must begin with changes in behavior at the individual level. There’s no question that people have the ability to adapt their behaviors, but few do.

Building an elite integration team is also critical to transforming culture. No longer do companies choose members of their integration teams based on availability. Instead, the companies most adept at integration assign star performers out of their current roles to partner with leadership and an effective integration management office (IMO).

Employee communication

M&A transactions carry huge opportunity costs: business is disrupted, employees are distracted, and performance is diminished. So it’s no surprise that distraction, disruption, and uncertainty can drive the economics of a transaction, potentially resulting in:

• Productivity declines, as anxious and distracted employees — confused about today’s priorities and tomorrow’s direction—spend inordinate amounts of workday time speculating.

• Workforce exit, as employees rapidly lose confidence in management that fails to communicate a clear direction early on. The first to go are usually the best and the brightest who don’t want to put their careers on hold while their leaders tread water.

• Market share shrinkage, as competitors go after both customers and employees—capitalizing on external concerns, internal problems, and, often, a general sense of neglect.

Executing on a strong and clear communications strategy—for all stakeholders, but for employees in particular—is a necessary element in combating the distractions and anxious behaviors that result from an integration effort and a key contributor to successful M&A integration.

Communication fills the void. On one hand, in an environment lacking meaningful information, the most trivial events can assume monumental importance. On the other hand, in an information-rich environment, the search for clues is suppressed, distractions are minimized, and the status quo is maintained.

Communication reduces the cost of uncertainty. When employees are spending time wondering and worrying, they aren’t focusing, performing, delivering, and holding ground against the competition. Real communication is not about making announcements; it’s about connecting with people and meeting their information needs, thereby enabling them to stay focused.

Communication is a stabilizer. Value is lost more precipitously during times of transition than at any other time in an organization’s life, and the battle for value can be won or lost depending on whether you capture the confidence and support of your workforce. Candid and transparent communication supplies honest answers to the hard questions that good people ask when they’re in the dark and worried.

Communication enables stakeholders to move forward. Effective communication helps translate plans into real action—by removing uncertainty, stabilizing strengths, capturing buy-in, and mobilizing support.

Effective change communication: Defining success, getting results

Following are the essential success criteria and critical action steps to take when communicating for change on the heels of a transaction.

Success criteria

• Key stakeholders are identified, engaged and contributing to the transition

• Two-way communication channels are operating effectively prior to Day One

• Dialogue with all parties is consistent and of high quality

• The approach taken is consistent with the employer’s brand, behaviors, culture and values

• Success measures are linked to behavioral change and tangible outcomes

• Employees understand and support the deal drivers and critical success factors

• Crisis and contingency process is in place

What needs to be done

• Identify and analyze all internal stakeholders

• Agree upon the key messages to support the deal while anticipating employee questions

• Establish a communication strategy and plan

• Establish core communication processes, roles and responsibilities, frequency and timelines

• Establish quality assurance and risk management procedures

• Prepare and deliver communication materials

• Identify and establish appropriate change champion and feedback networks

• Review and agree upon “touch points” with external communicators and market analysts

Change management to empower Workforce Transition

Throughout a business’s merger integration process, effective change management is critical to integrating people with future strategies. Effective change management increases people’s confidence in direction and outcomes, accelerates business results, and sustains the enhanced benefits of change.

A distinguishing feature of PwC’s approach to change management is the position that an organization’s formal approach to managing change should help it manage change through its people, as opposed to managing its people through change.

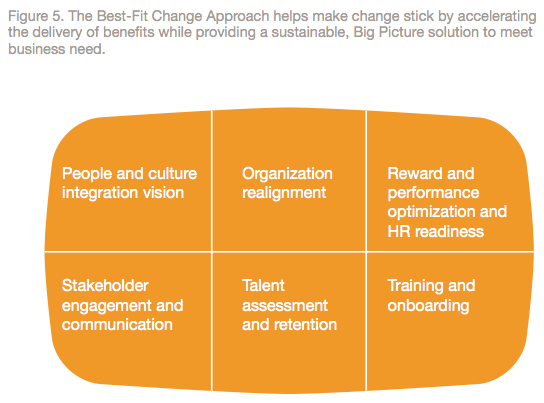

Understanding how all the pieces of the change puzzle fit together and knowing how each piece should be addressed constitute what we call the Best-Fit Change Approach, which:

• Focusesonachievingbenefitsand defines targeted measures to track them.

• Encourages the involvement of the people who will deliver change in the organization, thereby both driving purposeful communication and balancing

activities that should be driven from the top with activities that build on the ideas and successes of the teams on the front line.

• Builds sustainability by embedding into an organization’s performance management and training processes certain new ways of working.

Any effective change management effort should also include what we call a Hearts-and-Minds work stream. That is, a cross-functional integration team should be formed whose primary purpose is to blend all employee touch points in such a way that strongly appeals to the hearts and minds of new joiners to embrace their new employer and advance their individual and shared best interests.

Members of this team should be encouraged to walk in the shoes of new joiners while developing or adapting communications, processes or work practices. Doing so will make the early experiences of these new joiners positive ones. Team members should serve as resources to multiple integration teams, including onboarding, benefits, and other HR- focused efforts, and they should be involved in communication activities as both content developers and reviewers.

Current employees who previously worked at the target should also be asked to provide their feedback and perspective on HR-related matters.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter