Publications Making Your Chinese Merger “Marriage” Work: Achieving M&A Success In The Logistics Industry

- Publications

Making Your Chinese Merger “Marriage” Work: Achieving M&A Success In The Logistics Industry

- Bea

SHARE:

By Mui-Fong Goh, Chee Wee Gan, Jian Li, Tammy Ku – A.T. Kearney

Many market leaders view China, the world’s second-largest economy, as the “it” country for expansion, and identify the country’s logistics industry as the next growth frontier. As expansion-minded firms — domestic and foreign — strive to grow in China, they face certain challenges in conducting mergers and acquisitions. How skillfully companies approach these challenges will determine the extent to which their cross-cultural “marriages” succeed.

Since China opened its logistics industry to wholly owned foreign enterprises in 2005, there has been a surge in mergers and acquisitions (M&A), mostly involving foreign firms merging with or acquiring domestic ones (see figure 1). In 2008, the logistics business grew more than 15 percent year-over-year. Despite recent economic challenges, China’s market still has significant growth potential. A.T. Kearney’s initial projections indicate that in the next 15 years China’s domestic express market could reach $58 billion, equivalent to the united states’ current market. By 2025 China could supplant the united states as the top manufacturing country.

M&A has not only reshaped the Chinese logistics industry but has also introduced new technologies and more reliable products and services. Most observers expect further consolidation, and domestic companies are taking notice. state-owned enterprises are also expected to pursue M&A to maintain their strongholds while upgrading their capabilities.

The window of opportunity to invest in China’s logistics industry has never been wider. however, the M&A process in China is fraught with potential minefields. International firms that move now to assess and overcome these obstacles will be in position to capitalize on the unique opportunities China offers.

What’s Driving M&A in China?

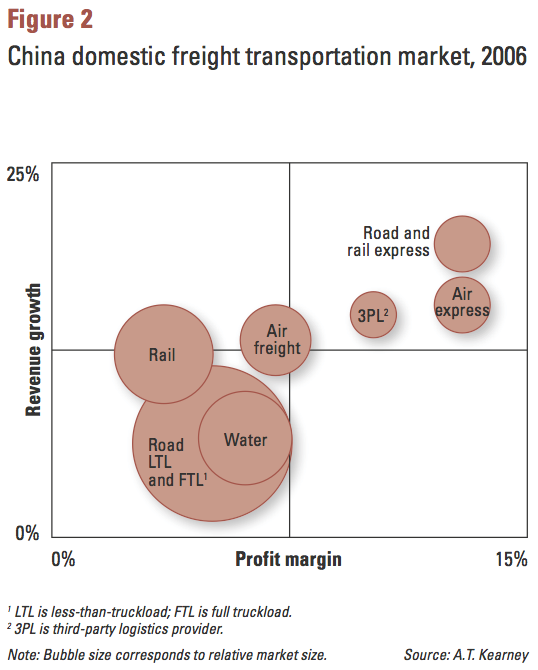

Growth in M&A in China is due to several factors. The domestic express and contract logistics segments, in particular, have skyrocketed. With revenues registering a 23 percent compound annual growth rate, the domestic express market is the fastest-growing and most profitable segment in the industry. Road express, which generally commands a price premium one-and-a-half to two times that of the less-than-truckload (LTL) sector, has revenues growing at 24 percent. Air express, with a price premium seven times LTL, is estimated to increase revenues at 22 percent. Third-party logistics sector revenues are expected to grow at a rate of almost 22 percent (see figure 2).

In addition, customers are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Chinese companies, especially top-tier firms, are now seeking speed, reliability and service as much as the best price when selecting logistics services. More customers realize that the supply chain is an indispensable competitive advantage, and they are willing to pay a premium for flexibility and customization. This favors foreign logistics firms, which offer unique expertise.

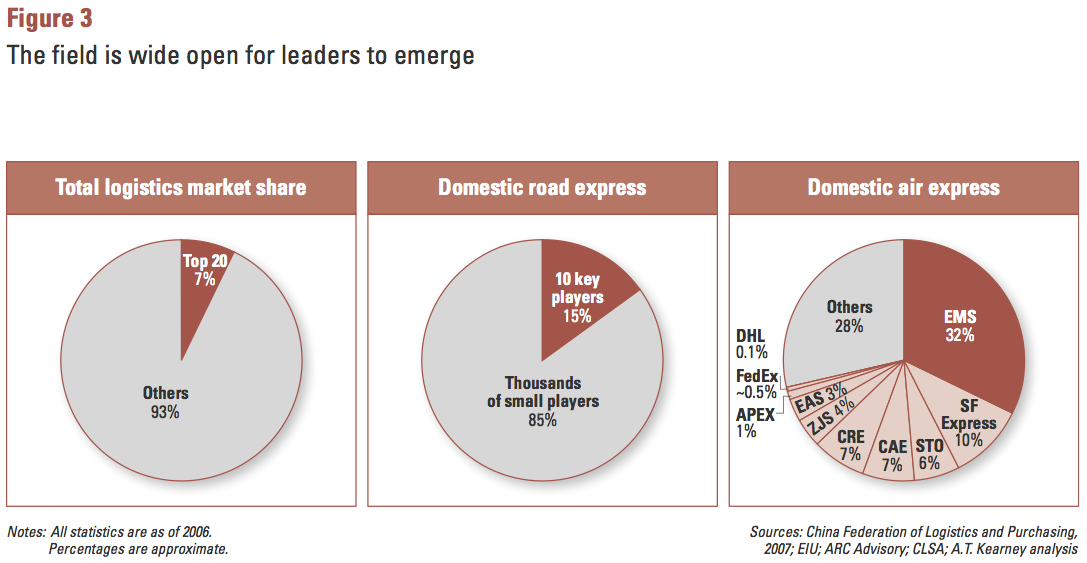

The fragmented industry has also left ample opportunity for leaders to emerge and consolidate. It is estimated that there are more than one million logistics companies in China. In the domestic road-express segment, for example, 85 percent of the market is held by thousands of small companies (see figure 3). As small niche players lead a market segment or geographic area, the larger state-owned logistics companies lack the capabilities to compete effectively. Because there is no clear market leader, there are many investment opportunities, but the time to capitalize is short, as the Chinese government is encouraging its domestic players to improve and expand. For both foreign and domestic firms, a bold and well-executed strategy is crucial for success.

Another factor is an increasingly transparent operating environment. It will become more difficult for domestic companies to succeed with artificially depressed cost structures, especially as China introduces new labor and tax laws. Foreign players are better positioned to compete in such an environment, as they already have corporate guidelines in place.

Finally, government policies and increased cost-consciousness from manufacturing companies are shifting manufacturing bases inland and consequently accelerating inland demand for logistics. Favorable local government policies in the west and north are coaxing companies away from China’s coastal hubs (see figure 4). Additionally, much of China’s recent economic stimulus plan is dedicated to invigorating the economy of the western part of the country, with billions of dollars earmarked for infrastructure investment. This will further encourage companies to establish bases in the region, and as a result, the need to build an extensive domestic network has taken on added significance. Though they represent just 8 percent of the population, China’s second-tier cities account for almost 54 percent of the country’s imports and are growing at an annual rate of 11 percent, according to Transport Intelligence. This favors companies with comprehensive networks, and those without such networks will have to expand quickly to keep pace.

Time to Move

The list of companies ripe for M&A is short, and when state-owned enterprises are excluded, it’s even shorter. When reviewing targets, keep in mind that brand name, customer mix, operational capability and geographic network are the important criteria. There are only a few national-level companies in China with the operational scale upon which an acquiring company can quickly build a domestic network. While attractive regional targets exist, they will need to be pieced together to form an extended network. With the economic slowdown, domestic logistics firms that have expanded aggressively but do not have network flexibility may become acquisition targets or may be pushed out of the market altogether.

Furthermore, it will become increasingly difficult for foreign companies to enter and compete against domestic rivals. A sizable portion of the Chinese government’s $586 billion stimulus package will go to state-owned enterprises to ensure they have enough capital to improve their competitive positions against foreign entrants. it has not been publicly disclosed which logistics companies will receive these injections; however, China Economic Review reports that Southern Airlines and China Eastern Airlines each will receive $440 million. As state-owned enterprises receive stimulus money, there will likely be a major reshuffling of market positions over the next two to three years.

While this value-rich opportunity currently exists in China, it is likely to be short-lived. Foreign logistics companies should move into China now, before state-owned enterprises become more competitive.

M&A: Different Approaches

Foreign companies have adopted various approaches in entering China. FedEx, for example, used an aggressive M&A strategy to build its international and domestic air-express business. In November 1999, FedEx and DTW formed a joint venture that mainly operated international express service. In January 2006, FedEx paid $400 million to buy out DTW’s half of the joint venture and acquire all of DTW’s domestic express business. Through this acquisition, FedEx assumed control of management, local distribution and 89 locations, and converted its Chinese operations into a wholly owned foreign enterprise. Thus, FedEx was able to improve its Chinese operations significantly, expand into second-tier cities and develop its brand name. Currently, FedEx is offering next-day, time-definite products to 40 cities and day-definite products nationwide, with service points in more than 200 Chinese cities.

Another example is TNT, which continues its global strategy of providing road-express options to its customers. In 2007 it acquired Hoau, China’s largest private LTL company. This increased TNT’s presence to more than 1,200 service points, including more than 200 locations with road-express offerings. TNT is planning to increase its commitment by emphasizing infrastructure, fleet, training and technology. Through its successful acquisition of one of the industry’s top players, TNT has been able to create a leading domestic position in China.

Rather than pursue M&A, DHL has chosen to continue a joint venture with Sinotrans. Established in 1986, the collaboration was the first of its kind in China’s logistics industry, combining DHL’s air-express knowledge with Sinotrans’ expertise in China’s foreign-trade transport market. DHL purchased a 5 percent stake in Sinotrans to emphasize its commitment to the joint venture in 2003. Since it was established, DHL has invested $1.3 billion in China and currently runs four service and logistics centers, with operations in more than 70 cities and pick-up and delivery covering more than 320 cities. In November 2008, DHL announced it would end its services in the United States. As a result, China will likely become DHL’s largest market outside Europe.

Another recent deal worth noting is YRC Logistics’ 2008 acquisition of Shanghai Jiayu Logistics, the third-largest private LTL company. YRC bought 65 percent of Jiayu for about $45 million and may purchase the remaining stake based on Jiayu’s subsequent financial performance. By acquiring a majority stake and tying performance to a subsequent buyout, YRC has created a strong incentive for local management to perform.

A foreign company acquiring a domestic target in China often sees costs increase significantly post-acquisition, sometimes by as much as 30 percent.

There are also lessons learned from the failures. Ineffective management of post-acquisition governance, incentives and administration changes are usually the culprits when a merger or acquisition fails. One high-profile M&A failure involves the joint venture between food conglomerate Danone and Chinese beverage giant Wahaha. Danone, which owns a 51 percent stake in 39 Danone-Wahaha joint ventures, has accused Wahaha of defrauding it by setting up its own companies to make products identical to those produced by their joint ventures, and selling branded drinks without Danone’s permission. Another example is the merger between Ernst & Young and Shanghai Dahua, which resulted in lost employees and customers due to poor management of different cultures and business practices.

M&A in China Is Not for the Timid

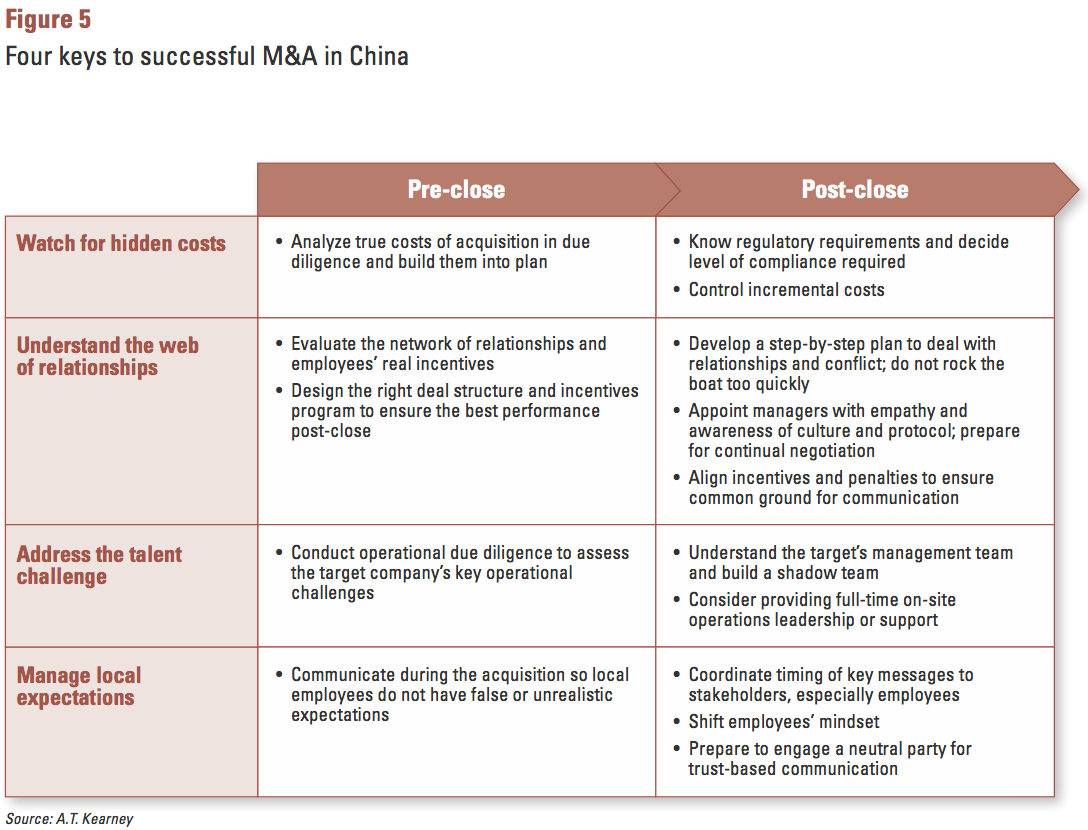

Although M&A is often the way to build a presence in China quickly, the process is fraught with risks and challenges. The following are four ways before and after a deal closes to increase the chance of M&A success in China (see figure 5).

Watch for hidden costs. A foreign company acquiring a domestic target often sees costs increase significantly post-acquisition, sometimes as much as 30 percent. This is because foreign companies typically have stronger compliance and responsibility policies than domestic companies, which focus on expediency. Because there is reluctance to explore gray areas in tax, labor, health and safety due to fear of corporate liability, compliance costs tend to arise after the deal is closed.

For example, many domestic logistics companies do not offer employee health benefits or safety programs. however, foreign entities usually cannot sustain these “cost savings,” as the legal and corporate risks are much higher. imagine the ramifications if a newspaper reported the number of annual deaths caused by a lack of health and safety programs.

China’s new labor law is another challenge for foreign companies struggling to control incremental costs. The law enforces strict compliance with labor-related issues, emphasizes formal contracts, and mandates a minimum wage and social benefits. It should be noted that due to current economic conditions, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security has advised local governments to postpone adjustments to the minimum wage, offering a respite for the time being.

The new law may actually end up benefiting international firms, as most already have such corporate labor guidelines in place. This fact levels the playing field for foreign and domestic firms and creates room for competition.

During the pre-close phase, it is wise to conduct due diligence to understand the hidden costs that may arise post-acquisition and build this knowledge into the business case. Once the deal has been completed, it is important to manage incremental costs by understanding local regulations and practices.

Understand the web of relationships. Many of the private domestic logistics companies are still owned and operated by their founders. As their companies grew quickly over the years, these leaders developed an extensive network of relationships among suppliers, employees and family members, often with little regard for operational efficiency.

For example, it is not uncommon for employees to own the line-haul trucks used by freight companies. This is sometimes encouraged by owners as a fringe benefit that allows salaries to stay relatively low. A common result, though, is that employees will delay the loading of certain line-haul trucks and wait for their own trucks to arrive, to maximize personal profit. of course, this is a cause of poor performance and unreliability.

New entrants must navigate these webs of relationships carefully, since they form the basis of employees’ steady incomes. Before closing a deal, companies should seek to discover hidden incentives within the company’s relationships. After a deal, change that is too sudden or abrasive could lead to widespread dissatisfaction — and perhaps even sabotage. savvy managers with awareness of company culture and protocol are needed to build relationships. An assessment of the complex relationships and power bases will help identify “change agents” in the company, whom can then be offered incentives to align their interests with those of the company.

Address the talent challenge. There is often a lack of operational talent in China, particularly in transportation-network management. Important decisions are often based on instinct rather than information and analysis, leading to hit- or-miss results.

While acquiring companies often send finance or human resources teams to the target company, they rarely do so for operations, under the assumption that the new acquisition already has enough capability to be successful. Yet, operations is often the toughest nut to crack. Acquired companies, proud of their operations and past success, can become defensive and resistant to change.

Rigorous due diligence is essential for assessing the target company’s true operational and human capabilities before a deal and ensuring that the acquiring company really gets what it pays for.

To improve operational performance after a deal, the acquiring company might consider providing full-time, on-site operations leadership or support with a focus on winning the trust of the local operations team.

Manage local expectations. Many employees in domestic companies think that working for foreign companies means better salaries and an easier workload. sometimes, the owner of the target company may promise employees huge salary increases or improved benefits to generate approval for a sale. When such promises go unfulfilled, the resulting distrust and low morale will hurt production.

Foreign logistics companies should move into China now, before the state-owned enterprises become more competitive.

An effective employee communication program implemented early in the process can mitigate false and unrealistic expectations. It is important to communicate with local workers during the acquisition process rather than leaving it to the target company’s management.

Since China’s domestic logistics companies are usually decentralized and have strong local power bases, there will be resistance to top-down changes that jeopardize local interests. such resistance can be counteracted by revamping the incentives system, building up trust and credibility, and engaging in honest communication. A strong leader with first-rate people skills can help bridge cultural differences and close the talent gap.

No Time to Waste

Any successful M&A requires dedication and hard work, but for foreign companies attempting to expand in China’s logistics industry, even more effort is necessary to overcome the often-hidden pitfalls. A realistic assessment both before and after acquisition will help acquirers blend the cultures of the two different companies. Conditions now are as good as they’ll ever be — there’s no time to waste in making the move into China’s huge, growing market.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter