Publications How Emerging Markets Companies Can Avoid Growth Traps

- Publications

How Emerging Markets Companies Can Avoid Growth Traps

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By John Jullens – Strategy&

How Emerging Markets Companies Can Avoid Growth Traps

Rapidly growing companies in the developing world can prepare themselves to do battle on a global stage by gaining access to vital capabilities through acquisitions or partnerships.

It is extremely difficult for emerging market economies to sustain the rapid growth that stems from industrialization. Most get caught in different kinds of what economists call growth traps: Either the rate of economic development plateaus, or it slips back well before low-income countries fully progress through middle-income to high-income status. The current slowdowns in many emerging countries, notably China, serve as cases in point.

While many factors help sandbag growth, one of the root causes is that emerging market countries focus their development strategies primarily on economic policy and institutional reforms, while ignoring the strategic management of their domestic firms. As a result, they fail to create a sufficient number of world-class companies to power the sustained, long-term growth they seek.

Emerging markets companies (EMCs) embody a contradiction that complicates their growth strategies. Typically, they are first movers in their home markets, and in many cases have won impressive market share and achieved phenomenal growth rates. But they are simultaneously latecomers, and most will find themselves playing catch-up with more experienced and better-resourced multinationals in global industries that are often already mature. The bigger EMCs become — and the further afield they attempt to grow — the more this inherent contradiction becomes evident and creates problems.

The challenges in competing with world-class multinationals are formidable, whether EMCs are moving up the value chain from basic manufacturing to cutting-edge technology and advanced R&D, or moving down the value chain to establish closer ties to customers. The most successful EMCs — companies like Mexico’s CEMEX, China International Marine Container (CIMC), Haier, Samsung, and Wanxiang Group — have followed a deliberate, stepwise, cumulative plan for building capabilities. They move from basic capabilities that enable production to more sophisticated ones that can support world-class innovation and design. As EMCs transition from one step of the capabilities-building process to the next, they need to navigate around growth traps, and they must choose among the alternative means of acquiring the capabilities they need: external contracting, internal development, mergers, acquisitions, or partnerships. Each has advantages, drawbacks, and potential trade-offs.

The EMC Growth Wall

In their early stages, EMCs are well positioned to gain market share in their rapidly expanding home markets due to their understanding of how to navigate local market imperfections and the absence of competition from global players. In their eagerness to exploit oppor-tunities, however, many focus too narrowly on top-line growth and neglect to build the foundational capabilities they will ultimately need to compete with foreign multinationals that will enter their markets over time. Companies that focus early on capabilities are more successful over the long term. Comparing the fortunes of two of China’s leading auto companies, BYD and Great Wall, during the early stages of their growth a few years ago shows how these different approaches play out in practice — and the contrast is striking.

BYD, the Shenzhen-based automaker best known for electric and hybrid vehicles, focused on increasing sales, creating a broad product line, and rapidly expanding its dealer network in China and abroad. The longterm strategy was to create a leadership position in the global auto industry by 2025. Sales boomed at a 55 percent compounded annual rate from 2006 to 2010, but then plateaued; profits, on the other hand, peaked in 2009 and have since fallen precipitously, in large mea-sure because capability building has lagged.

Great Wall, based in Baoding, had great success between 2006 and 2010 by focusing on sport utility vehicles and pickup trucks at exactly the time domestic demand for such vehicles was soaring. The company, however, took a more cautious path, remaining profitoriented and concentrating on building its capabilities. “Be stronger (first), then bigger,” as chairman Wei Jianjun summarized the approach. Sales grew more slowly early on, but eclipsed BYD’s in 2012, and profits have continued to grow. More recently, the company has struggled to replicate that success with sedans and it is now facing increased competition in the SUV market, and will need to develop or acquire even higher level of capabilities to maintain its momentum.

Developing World-Class Capabilities

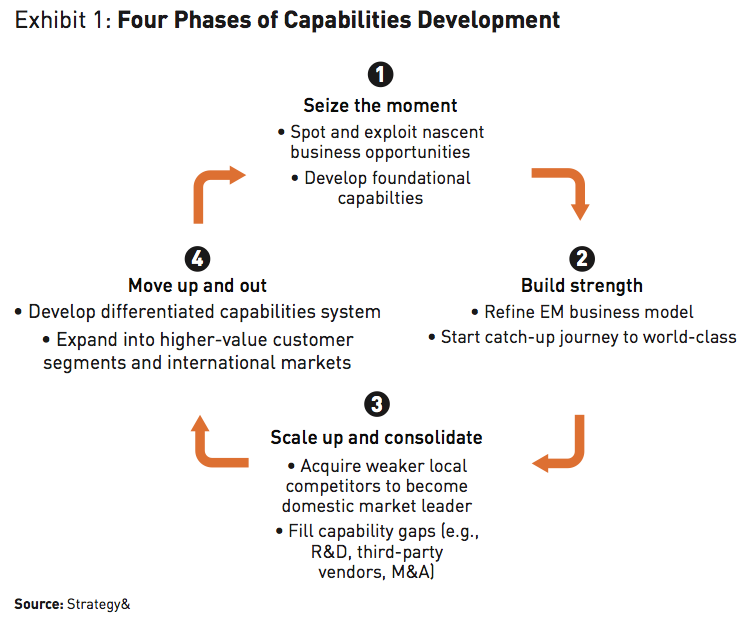

Successful emerging markets companies have followed a four-step process for developing advanced capabilities over time: They seize the moment, build strength, scale up and consolidate, and then move up and out (see Exhibit 1).

As EMCs transition from one phase to the next, the sources of competitive advantage change, and they need to navigate around a succession of growth traps. In the transition between seizing the moment and building strength, many companies are hampered by their neglect of building the foundational capabilities they will need for subsequent phases. As they move from building strength to scaling up and consolidation, they need to adapt and deepen their capabilities systems so they can optimize their advantages and defend their market positions against competition from foreign MNCs. In the final transition, as they prepare to move up and out, they need to develop differentiated capabilities systems in order to compete at world-class performance levels.

Wanxiang Group, China’s leading auto parts supplier, has navigated these transitions with great success, often by acquiring capabilities outright along the way. Wanxiang focused on increasing quality and cutting costs in the 1980s and went public in 1994, establishing a tech center with an annual R&D investment of 4.5 percent of sales. By 1998, the company held a 70 percent market share of the domestic business, and began supplying Sino-foreign joint ventures involving automakers such as General Motors and Ford. Wanxiang expanded into the U.S. in 2001, buying a 21 percent stake of brake-maker UAI; in 2012, it acquired A123 Systems, a U.S. maker of advanced lithium-ion batteries. By 2013, Wanxiang had become China’s secondlargest private company, with annual revenues of more than $10 billion.

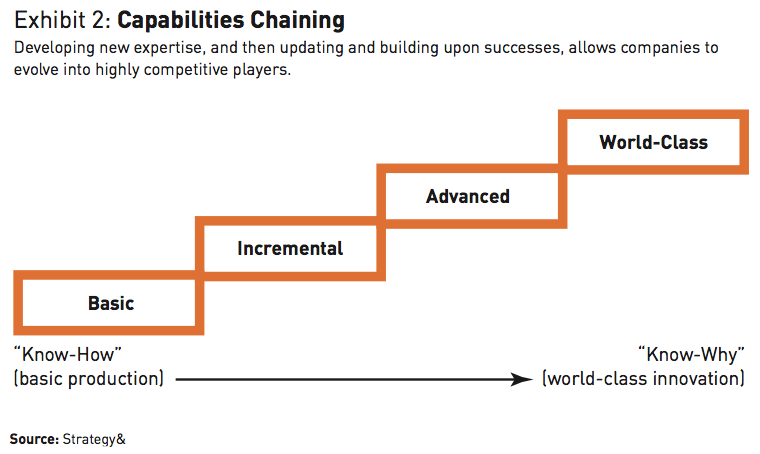

EMCs that want to emulate success stories like Wanxiang’s must figure out how they can best progress from relying primarily on country-based comparative advantages, such as low-cost labor, to developing their own firm-specific competitive advantages; and how they can improve from copying basic production capabilities from other companies to mastering world-class innovation capabilities. The answer is to develop — and continuously refine and update — a capabilities road map, which shows how capabilities can be “chained” in a stepwise, cumulative manner (see Exhibit 2).

First, however, EMCs must decide whether they need to build or buy capabilities at all — or whether they should, in effect, “rent” them instead. Twentiethcentury pioneers like Toyota and Honda needed to build capabilities for each step of the value chain. But the modularization of global value chains in recent years has made it much easier to add many capabilities through external contracting. EMCs can instead pick and choose among capabilities supplied by third parties. The limitation in this approach is that capabilities added in this fashion will be, by definition, somewhat generic and non-strategic.

One approach for gaining more strategic, distinctive capabilities is to develop them in-house. Samsung is a good example of how well this can work. The company (originally named Korea Telecommunications Corp.) made its mark in the late 1970s as an efficient manufacturer of black-and-white televisions. By the mid-1980s it had branched out to PCs, video recorders, and other devices, and was exporting to the U.S. and Europe. In 1987 the company heightened its focus on R&D by launching the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology, which has since grown to include a global network of R&D facilities, funded by 9 percent of company revenues per year. In 1996, Samsung moved to gain world-class capabilities in design: After studying the design organizations of market-leading MNCs, Samsung’s CEO committed to a companywide initiative to create design capabilities in-house. The effort involved the creation of training programs for designers, reassignments, reorganization, and convincing skeptical operations executives, engineers, and suppliers to get on board.

Building this extensive capabilities system gave Samsung the “right to win” in the markets it targeted subsequently, like flat-screen televisions and smartphones. (Samsung’s Galaxy smartphones led to the introduction of the “phablet” category, which gained market share and have been widely copied.) Samsung’s design capabilities also enabled it to survive the market upheaval that followed Apple’s introduction of the iPhone and continue to gain market share — while other competitors like Nokia, Motorola, and Ericsson fell by the wayside.

The chief disadvantage in building capabilities in this fashion, particularly for EMCs in fast-moving markets, is, of course, that it takes time, as opposed to acquiring and absorbing strategic capabilities through M&A or various types of partnerships.

Buying Capabilities

Although mergers and acquisitions are a particularly tempting route for gaining capabilities quickly, they also present challenges and risks. And the experiences of fastgrowing Indian and Chinese companies has been mixed.

Capabilities-building via M&A addresses two of the main challenges that EMCs often face: the pressure to catch up with more established competitors quickly, and the need to develop multiple capabilities simultaneously. And the environment has been conducive to such efforts. In the wake of the post-2008 downturn, EMCs have been able to choose among many potential acquisition targets at attractive prices. Financing is cheap, thanks to monetary policies that have kept interest rates low. In addition, government policies in emerging markets often push companies to export and become more technologically advanced. China, for example, has encouraged “going out” strategies, both directly for stateowned firms, and indirectly for other firms. In South Korea in the late 20th century, the outward-oriented economic policy included temporary protection for domestic industries, and incentives and hard targets for exporting. This policy helped South Korea grow rapidly and become one of the very few countries that successfully avoided the dreaded middle-income trap.

Those EMCs that have succeeded in building capabilities via M&A have done so by making M&A itself a key capability. They have been able to routinize the knowledge transfer and absorption process after each acquisition. CEMEX, the Mexican multinational building-materials company, is perhaps the most celebrated example. From a position as a domestic producer of commodity materials in the early 1990s, CEMEX focused on profitability and capabilities-building to capture growth opportunities after the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. The company embraced information technology and M&A to pursue a strategy of differentiating itself as a provider of solutions for builders and local governments. CEMEX pursued inorganic growth first in Mexico, then in Spain, Latin America, and elsewhere. It developed a deep capability in post-merger integration, inducting acquired companies into its management system and paying particular attention to capturing and internalizing their knowledge.

EMCs that successfully build capabilities via M&A need to be able to identify the right capabilities that potential acquisitions offer, and they must be able to absorb the technology and knowledge they are trying to obtain. Doing so successfully requires three sets of organization capabilities that many EMCs often lack. The first is turnaround management: Industry leaders typically are not for sale, so potential acquisitions are often in financial distress or troubled in some other way. (Wanxiang bought A123 Systems out of bankruptcy, for example.) The second is integration management: Most EMCs are not experienced in post-merger integration, and many face the classic conceptual problem of trying to absorb and integrate something they don’t yet fully understand. Chinese M&As in the auto sector, such as Geely’s purchase of Volvo, have proved challenging for this reason. International experience is the final challenge. Many EMCs lack fungible talent and sophisticated governance systems, and they face language and culture issues.

The Partnership Solution

Forging partnerships may be more suitable for EMCs in some cases than outright acquisitions. Partnerships offer opportunities for collaboration on a project-by-project basis, and thus for knowledge transfer — often with industry leaders. And there is no need to manage or integrate the foreign partner’s business. For their part, many foreign companies, especially medium-sized ones, urgently need to be successful in emerging markets, but often lack the capabilities and resources that local markets require.

This intersection of needs between EMCs and developed market firms thus creates many potential “winwin” opportunities to share complementary firm capabilities, country-specific advantages, and geographic proximity. There are at least four different types of potentially synergistic partnership opportunities for EMCs, depending on the industry and market maturity:

• Good-enough opportunities, in which EMCs and developed market companies jointly develop lowend or mid-market versions of existing products for developing markets.

• Latent demand opportunities, in which the partners jointly penetrate developed markets by activating latent demand for low-end or mid-market products.

• Leapfrog opportunities, in which partners try to capitalize on latecomer advantages to develop new products and technologies in greenfield developing markets.

• Breakthrough opportunities, in which partners combine high-end developed market and lowcost emerging market capabilities to create truly new products.

In coming years, emerging market companies will continue to look for acquisitions to accumulate assets and develop their organizational capabilities and resources. Given the prospect of continued slow and uneven economic growth in developed markets, attractive acquisition candidates will continue to be available, and developed markets companies will continue to be interested in partnerships to build their presence in developing markets.

To make the most of these opportunities, EMCs will need to become much more capable at managing and integrating acquisitions and managing partnerships. Many EMCs — particularly Chinese companies — have prioritized the acquisition of technology itself. But while gaining technology is necessary for companies to move up the value chain and compete effectively with MNCs, it is not sufficient. Companies must ensure that their acquisitions complement or enhance their existing stock of capabilities and other resources. Developing management skills that enable the addition and absorption of vital capabilities will be the single most important factor that allows EMCs to avoid growth traps and realize their ultimate objectives. Indeed, as companies plot strategy, they should recognize that the ability to assimilate new technologies — what might be called an organization’s “absorptive capacity” — is itself an important organization capability.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter