News Dividing to Conquer

- News

Dividing to Conquer

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

by: Florian Kolf and Georg Weishaupt

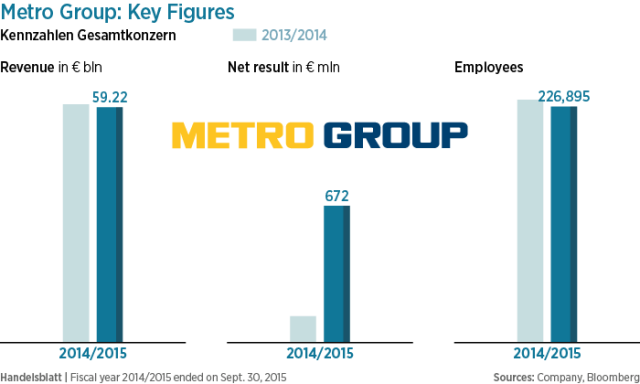

German retailer Metro is splitting into two. Investors think the company’s consumer electronics and supermarket businesses are worth more separately than together. The break-up also helps CEO Olaf Koch, who can relegate a cantankerous minority shareholder to the sidelines.

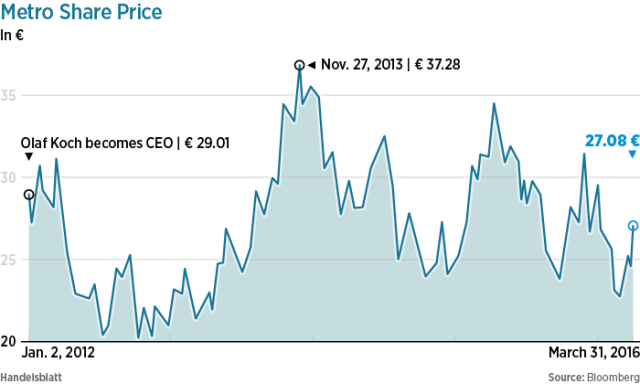

Shortly after he took over as chief executive of German retailer Metro in January 2012, Olaf Koch took the symbolic step of moving his office into the headquarters of the group’s wholesale trading business.

The message was loud and clear: Metro would refocus on the “Cash & Carry” operations with which it started out more than 50 years ago.

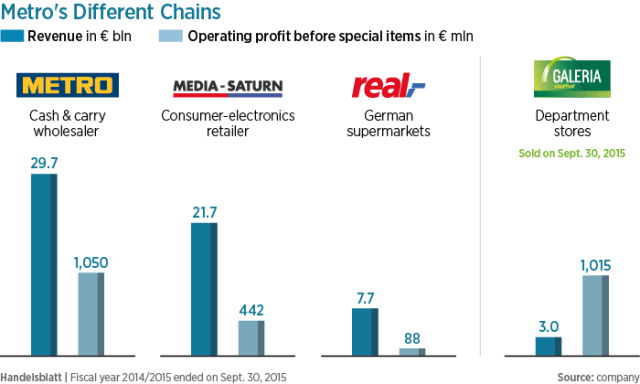

And now, four years on, Mr. Koch has completed Metro’s return to its roots by announcing a plan to split the group in two, separating its wholesale and food businesses from its consumer electronics chain, which he wants to spin off into a separate listed company with €22 billion in sales.

Mr. Koch, 45, plans to run the wholesale business and the Real supermarket chain, which together generate some €37 billion, or $42 billion, in sales.

“We will create two stock market-listed international market leaders,” he said. He doesn’t want to manage the new consumer electronics company himself, telling Handelsblatt: “I don’t define my job through power.”

The split would amount to a liberation for Mr. Koch.

“Metro has been in a strategic quandary for some time — the division offers good potential for a better development of the different segments,” said Vienna-based mergers and acquisitions expert Christopher Kummer.

Investors agreed.

After the company’s announcement on Wednesday, Metro shares rose as high as €28, an increase by more than 14 percent. On Thursday, they were trading down 1.7 percent at €27.03 at 10 a.m. in Frankfurt.

Mr. Koch said the two segments had limited synergies and dividing them would provide each with a clear and focused story for investors. “It’s definitely an advantage if investors in future will be able invest clearly in wholesale and the grocery business, or in consumer electronics,” he told Handelsblatt.

But that’s only half the truth. By taking this step, Mr. Koch is also battling his way free of the combative Erich Kellerhals, the minority shareholder of Media Saturn who has been a thorn in his side for years. Mr. Kellerhals will retain his veto rights but will be pushed into a new company, far removed from Metro’s future core business.

“Herr Kellerhals won’t be able to disrupt proceedings,” Mr. Koch told a news conference Wednesday. That’s because the split is happening at group level, not at Media-Saturn. So Mr. Kellerhals won’t be able to thwart Mr. Koch’s grand plan.

Mr. Kellerhals himself appeared unfazed by the plan. “We have taken note of Metro’s announcement with interest and will closely follow further developments,” said a spokesman for Convergenta, which holds the Media-Saturn shares owned by Mr. Kellerhals and his family. “We don’t see our rights as shareholders of Media Saturn Holding being affected by Metro’s plans.”

Those are peaceful tones in a constant conflict between Mr. Kellerhals, 76, who co-founded the electronics retailer in 1974, and Mr. Koch. Mr. Kellerhals and his family own just over 21 percent of Media-Saturn but they have more extensive voting rights which prevent Metro from taking any major decisions against his wishes.

There are a number of ongoing legal cases between the two. One big bone of contention is Media-Saturn Chief Executive Pieter Haas. Mr. Kellerhals regards him as unsuited for the job and has been fighting to have him removed. A court in the southern German city of Ingolstadt will hear the case on June 28.

If Mr. Koch has his way, Mr. Haas will run the new consumer electronics company after the spin-off.

The proposed split, under which shareholders would receive one share in each company for each existing share, needs to be approved by management and the supervisory boards.

It is supposed to be completed by mid-2017 at the latest.

Jürgen Steinemann, Metro’s supervisory board chairman, has already signalled he’s in favor.

“I firmly believe that splitting the company into two independent and focused companies would be in the best interests of all involved,” he said. Metro’s three anchor shareholders – the Haniel, Schmidt-Ruthenbeck and Beisheim families – have also indicated they support the plan.

But Mr. Koch still has a long way to go. His proposal for a fundamental reorganisation of Europe’s fourth-biggest retailer has so far only been discussed in a small group and not fleshed out in detail. It will involve the reallocation of many management and supervisory positions.

Even the names of the two new companies haven’t been decided yet.

The employees were informed of the plan Wednesday at workplace meetings as the split was publicly announced.

Metro was formed in 1996 through the merger of the Metro wholesale chain with retailers Asko Deutsche Kaufhaus, department store chain Kaufhof Holding and Deutsche SB-Kauf. It was something of a one-stop shop, and Mr. Koch’s predecessors jettisoned many subsidiaries such as shoe retailer Reno, DIY chain Praktiker and the Adler fashion stores years ago.

Now Mr. Koch is completing the streamlining with a radical break, and has won praise from industry analysts.

“The split into the divisions electronic goods and grocery trading makes sense,” said Joachim Stumpf, an analyst at Munich consultancy BBE. “Basically it continues the Metro’s reorganization after Kaufhof was sold last year.”

In future, Mr. Stumpf said, Metro’s various businesses will be able to better focus on their respective markets.

The break-up was only made possible by the sale of Kaufhof to Canada’s Hudson’s Bay group for €2.8 billion last year. That money reduced the group’s debt to a level at which Metro could consider a stock market flotation of its consumer electronics retailing business.

The balance sheet got an added boost from Metro’s recent sale of its wholesale business in Vietnam. “We worked hard to make this step possible,” said Mr. Koch.

Improvements in Metro’s results also helped. Media-Saturn has managed to increase revenue for six quarters in a row on a same-store basis and is making sustainable profits after being Mr. Koch’s biggest headache for years. The business has also been making headway in online retailing, which it had neglected for years.

Mr. Koch wants to concentrate on wholesale trading, and especially on the high-profit supply of large customers in the catering business. Metro beefed up this segment recently with the acquisition of Classic Fine Foods in Asia and Rungis Express in Germany.

The Real supermarket chain remains a problem, though. Its labor costs of up to 30 percent are above those of many competitors, which prompted Mr. Koch to cancel the chain’s collective-bargaining contract with employees to try to negotiate a new one. So far, there’s been no agreement.

Metro’s break-up is in line with an industry trend. Many conglomerates are refocusing on core businesses.

“There’s increasing pressure to adopt a clear strategic focus,” said Christopher Kummer, president of the Institute of Mergers, Acquisitions and Alliances in Vienna. Size for its own sake without commensurate profitability made little sense, he added.

Mr. Koch evidently agrees. He sees good prospects for growth for both new companies, both organically and through acquisitions.

“The size of companies played a different role 20 years ago,” Mr. Koch told Handelsblatt. “I think that size still plays a role in trading. But I have to reach the size in my respective sector, in our case meaning the wholesale and food sector and consumer electronics.”

He added: “We want to deliver more goods directly to our customers in wholesale. We also want to offer far more service in consumer electronics. And we’ll go into new countries with wholesale.”

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter