Publications Cross-Border Transactions: Spotlight On Central Eastern Europe

- Publications

Cross-Border Transactions: Spotlight On Central Eastern Europe

- Bea

SHARE:

By Dave Read, David Clanchy and Brendan O’Mahony – Ernst & Young

“A World of Opportunity”

Today’s dynamic transaction market presents a world of opportunity. As corporations and other investors turn their attention to international opportunities, they are looking beyond traditional markets to achieve high growth and competitive advantage. Ernst & Young’s “Cross-Border Transactions” series aims to shed light on the complex, yet rewarding transaction landscape in selected markets.

“Spotlight on Central Eastern Europe”, the third report in our series, provides an overview of the opportunity sectors, political context, and practical transaction considerations and challenges surrounding deal-making in six countries in the region: Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia from the perspective of inbound investors.

A combination of political stability, central geographic location between Western Europe and South East Europe and Asia, educated work force with relatively low wage costs, and fast rate of economic development makes Central Eastern Europe a highly attractive destination for investors looking to exploit the market opportunities for growth in the expanding European Union.

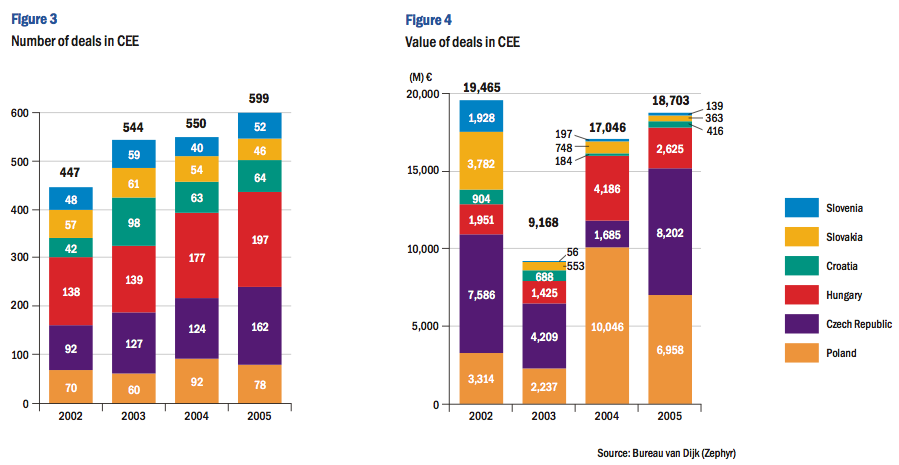

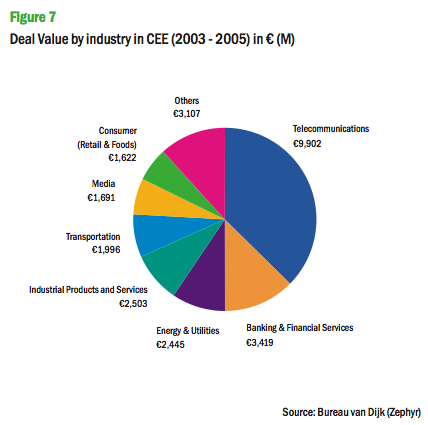

In 2005, €13.8bn total deal value in these six countries represented a 32% increase on 2004, driven by activity in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic. While a wave of privatizations took place before accession in 2004, there is still considerable scope for consolidation and expansion in the region in many industries.

With Ernst & Young Transaction Advisory Services practices in more than 70 countries, we are well positioned to understand the range of issues involved in investing in developing economies, from target identification to due diligence and post-deal integration.

In Central Eastern Europe our transaction team is comprised of professionals with extensive experience in national and cross-border deals. Our strength on the ground and close knowledge of industries, markets and technical issues help our clients make the most of the varied opportunities in the region.

Central Eastern Europe’s Emerging Appeal

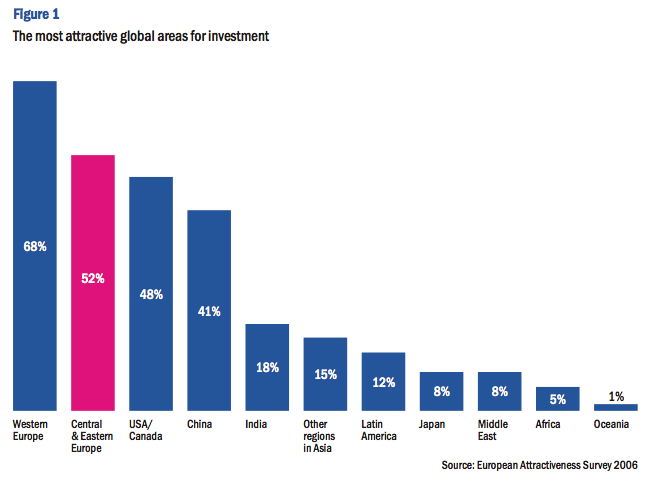

Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Croatia are moving steadily up the agenda of international investors. They are the focus of this report as the most significant economies in Central Eastern Europe (CEE) – the group of former communist countries lying to the east of Germany and north of the Balkan states. The region now ranks second only to Western Europe as a preferred destination for investment, according to international executives polled in Ernst & Young’s recent 2006 European Attractiveness Survey.

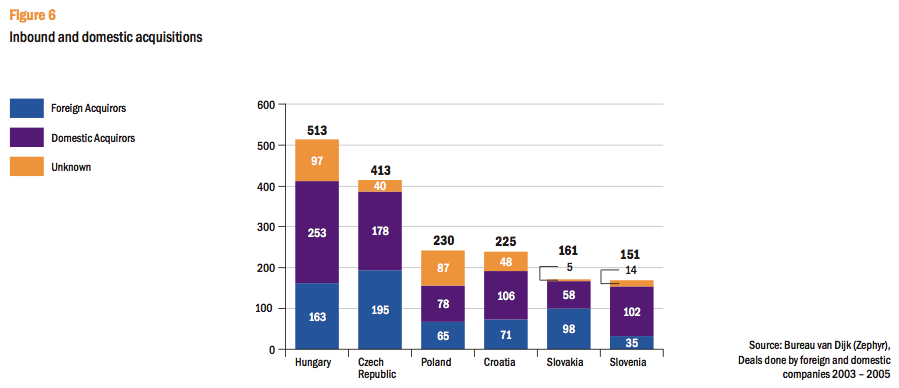

Both numbers and size of acquisitions have been growing since 2003 and 2005 continued the trend, primarily as a result of a number of large deals in the finance and telecommunications sectors. Activity was particularly high in Poland and the Czech Republic, where M&A value surged to nearly $10bn (€8.2bn). Privatization is still playing a part in these totals – two of 2005’s biggest deals were the sales of Cesky Telecom to Spain’s Telefonica for $3.6bn and Budapest Airport to BAA International for $2.2bn. But with fewer publicly owned companies remaining to transfer to the private sector the future will see greater emphasis on secondary sales by initial investors. Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic are among the top five destination countries for manufacturing activities according to the 2006 European Attractiveness Survey.

Going forward, there is considerable scope for consolidation among smaller firms in a number of industries across the region. We predict an increasing flow of cross-border transactions within the region driven by the growing confidence of Polish, Hungarian and Czech firms and their need to attract new capital for expansion. Regionally based firms are also increasingly expanding into Romania, Bulgaria and Serbia.

Why invest?

High activity levels reflect the growing appreciation by investors of the opportunities offered by both individual countries and the region as a whole. Several factors are at work here.

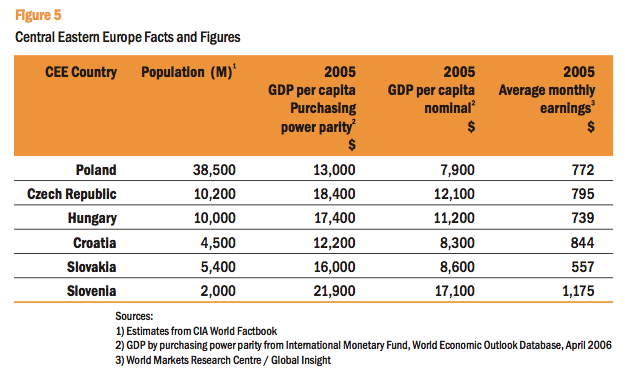

• Integration with the EU. With the accession of 10 new countries in May 2004 (all the nations covered here except Croatia, which is due to join between 2009 and 2011), ‘for foreign investors the geographic center of Europe has become its economic centre, with investor preference focused on Germany and Poland following a shift eastwards’ according to the European Attractiveness Survey. Although there are still issues with bureaucracy and political uncertainty in some areas, the business climate has been transformed since the late 1990s. The common European legal environment and subsidy payments have further aided transition since 2004. Comfort levels have reached the point where mid-sized German companies, particularly, are seeing Central Eastern Europe as a natural extension of their market. The modest 70 million total population of the six countries is more than made up for by the regions favorable strategic position and fast growth rates (at 4-6 per cent, GDP growth is double that of Western Europe).

• Bridge to the East. Poised geographically between Western Europe and the newly emerging economies of Russia, the CIS and the Balkans, Central Eastern Europe has become a staging post for western investors looking to venture east and south. The drive eastward is being spurred by the fact that in some CEE industries, maturity has been reached much faster than expected and market share can no longer be bought at bargain prices: mobile phone penetration in Hungary for instance is over 90 per cent, while real estate yields over the region are converging on those of Western Europe. Accordingly, more speculative attention is switching to the next accession states such as Romania and Bulgaria where risk-reward profiles are those of CEE a decade ago.

• Alternative to other Emerging Economies. With wages costs significantly below those of Western Europe, flexible labor laws and a well-educated workforce, CEE is emerging as a credible alternative destination for production sites and service centers. For long runs of low-cost commodity products China remains unbeatable, and on an individual country basis is the most popular investment destination country. As a region, however, CEE comes second only to Western Europe, and Poland and the Czech Republic are in the top seven most attractive investment destinations. ‘Nearshoring’ in the CEE scores highly with European strategic investors in industries where logistics, control and language are critical. The countries compete with each other to provide manufacturing facilities for more developed markets, and are each developing call and service centers, software development and business process outsourcing facilities.

• Familiar Transaction Environment. In terms of the transaction lifecycle, these CEE countries are moving closer to Western Europe for transparency and speed, advisors say. While there continue to be challenges and delays with sales of state- owned assets (as in Poland where two privatizations were cancelled last year), this is not the case for the private sector. A new generation of younger business people has grown up in the market economy where deals are part of the business environment. Professional advisors are experienced and widely available, as is financial information on potential targets. With rare exceptions deals involving private owners raise few intractable problems that would not be found in Western Europe.

In short, for foreign acquirers CEE countries combine many of the attractions of developed economies – transparent legal structure, familiar transaction environment, skilled and flexible workforce – with the rapid growth and low wage costs of emerging economies. With the exception of Poland the impact of private equity is limited, partly because of the dearth of deals meeting funds’ size criteria. This is expected to change in the medium term, however with the expansion of the currently sparse population of mid-sized companies, and the flow of larger deals. In addition to energy, financial services and telecoms the deal agenda also includes real estate, brewing, biotechnology, consumer goods manufacturing, IT and software and media. Greenfield investment largely focuses on manufacturing, particularly automotive, and contact and service centers.

Country Reviews

Poland

The largest of these CEE countries in terms of population and economic potential, Poland is an increasingly attractive investment destination. International deal numbers rose considerably from 2003 to 2004, placing the country fourth in Europe for FDI after the traditional leaders UK, France and Germany, but ahead of Spain and Russia. Poland’s advantages of market size, relatively low labor costs and central geographical location have been strongly augmented by EU accession, making it a favored site for FDI for export-oriented industries; trading relationships with Eastern European countries are a bonus for investors, and vice-versa. Two of the top five deals of 2005 involved regional investors, a trend set to continue as integration deepens. Investors also like Poland’s strong economic growth, the result of early economic and political reform, and the strong inflow of EU funds. With entrepreneurial activity thriving, several sectors, including manufacturing and real estate, are beginning to consolidate, helping to explain why private equity activity rose sharply last year. On the downside is a degree of political uncertainty, and restructuring and privatization of ‘sensitive sectors’ (coal, steel, railroads and energy) has recently stalled. However, bureaucracy and lack of transparency are issues of declining prominence, and required infrastructure improvements will present opportunities for the future.

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic’s economy is booming. It is one of the most stable and prosperous of the post-communist states (the 2005 GDP growth rate reached 6% in real terms). Deal values increased from close to €1.4bn in 2004 to €8.2bn in 2005 with nearly half the total accounted for by two telecoms transactions. However, the strong cross-border inflows registered since 1999 in both deals and greenfield investment is likely to carry on as the EU’s eastward thrust continues. Driving the momentum are potential privatizations (Aero Vodochody, national carrier CSA and Prague Airport could be lined up soon), consolidation of equity holdings as minority shareholders are reduced in previously privatized companies, and increasing activity in the mid-market as Czech entrepreneurs exit or acquire to move their companies to a new level.

Hungary

The third largest market in Central Eastern Europe, Hungary is one of the most open and most closely integrated with Western Europe. Having privatized early, its stability, well-educated and linguistically skilled workforce, highly developed private sector (80 per cent of the economy) and healthy growth rates have long made it attractive to foreign investors: cumulative FDI totals more than $55bn since 1989. In Europe, Hungary now ranks fifth for FDI market share, and along with Poland is rising sharply up the global attractiveness league. In 2005 transactions totaled 197, up from 177 in 2004, the biggest being the privatization of Budapest Airport where the sale of a 75 per cent share raised $2.2bn. Whereas in the 1990s foreign investment was driven mainly by market-based privatization, more recently Hungary has had to raise its game faced with the new competitiveness of other countries in the region. It has had some success in shifting the focus to investment in advanced technology areas such as automotive, R&D, shared services and logistics. Hungarian firms are also becoming active cross-border investors as they participate in the trend to regional expansion and consolidation.

Croatia

Before the dissolution of Yugoslavia, Croatia, with Slovenia, was the most prosperous and industrialized area of the country. Recently, public and private attention has centered on the important tourism industry, reflected in the presence of two hotel deals among last year’s top five transactions. Other active areas include food processing, pharmaceuticals and financial services. The two biggest Croatian-owned groups, Agrokor in food and Adris in tobacco and tourism, are seeking to expand and consolidate regionally, creating opportunities for divestment and acquisitions. For the moment, the government seems unlikely to sell off majority stakes in sensitive energy and infrastructure sectors, although as with other economies EU accession, due between 2009 and 2011, should accelerate structural and fiscal reform.

Slovakia

Slovakia, with its population of 5.4 million is another striking CEE success story, evidenced by GDP growth of 6.1% in real terms in 2005. By 2008 three Slovak auto plants will be turning out more cars per head than anywhere else in the world. Along with EU membership, chief attractions for investors are labor costs which are significantly lower than other CEE countries, an advanced manufacturing tradition and a business-friendly environment reflected in the attractive 19 per cent flat-rate tax (corporate as well as income). Other significant greenfield investment is going into office development for shared service and contact centers in Bratislava. Deal activity has been less intense, running at around 50 transactions a year. Privatizations, including secondary ones, are still a factor.

Private equity, as in much of the region, is limited in scope – although last year’s second-largest deal, the sale of a 36 per stake in Orange Slovakia, was a private equity exit.

Slovenia

The wealthiest area of former Yugoslavia Slovenia is now one of the most successful of the CEE transition states, with good infrastructure, a stable political system and relatively high standard of living. It joined the EU in 2004 and the European Commission and European Central Bank have recently confirmed that Slovenia will adopt the Euro from January 2007.

However, the attractions of EU membership and economic stability are offset by a muted desire for foreign control of local companies, reflected in the recent plans to privatize the country’s second largest bank and the incumbent fixed line telecommunications operator. In time, the need to restructure high-cost state owned industries without recourse to state funding will create investment opportunities, but for the moment intentions by the centre-right government elected in 2004 to speed up privatization are only just starting to materialize. On the whole, therefore, recent deal flows have been slow and values small.

Toward Transaction Success

As to be expected in countries which are either already members of the EU or about to join, deal making in Central Eastern Europe has fewer of the challenges of doing business in other emerging economies. For the most part, and with variations between individual countries, inward investors will find themselves on familiar territory.

Professional advisers are well established on the ground, industry and financial information is widely available, and language differences are seen as less of a problem. Perhaps most importantly, along with rapid growth in trade and integration with Western Europe, EU accession has increased competition for inward investment and as a result governments are increasingly cracking down on residual corruption and eliminating bureaucratic barriers. Foreign Direct Investment has been relatively lower in some countries, such as Slovenia but overall governments are becoming more investor-friendly. This trend is likely to continue as even lower-cost countries such as Romania and Bulgaria join the EU.

Target identification

Deal preliminaries pose few insoluble problems. The presence of networks of professional advisers in all the main centers makes researching the market and identifying targets relatively straightforward, and except in the case of smaller companies, vendors are generally aware of what the transaction process entails. With the reduction in state planning, central European entrepreneurial traditions have quickly reasserted themselves; some entrepreneurs are already on their second, third or fourth deal. The exceptions to this straightforward transaction environment are privatization deals, and sometimes the secondary sale of stakes in companies that are already privatized. Whatever their form these deals are generally more bureaucratic and time-consuming and sometimes less transparent than private-sector transactions. The region as a whole is becoming more open, but in some countries foreign investors still claim that locals with political ties get preferential treatment over outsiders. Political uncertainties have meant that several recent privatization deals have been withdrawn at the last moment.

One increasingly common approach to target identification is for companies identifying a need for a presence in Central Eastern Europe to ‘jurisdiction-shop’ – that is, assemble a team of HR, tax, legal and other specialist advisers to conduct a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of the country options and incentives available and on that basis proceeding to a detailed search for individual targets or investment destination.

Due diligence

As elsewhere, thorough due diligence is an essential prerequisite of any successful deal in CEE. It is important to be aware that some of the earlier privatizations in the region may have left companies with unresolved issues ranging from fractured ownership to bad debts and other contingent liabilities. Transfer pricing and poorly documented trades between related companies are two areas to examine in the due diligence process. Tax is usually fairly straightforward – most companies do not keep multiple sets of books for local tax authorities, as in some emerging economies – but there are frequently mechanisms used to minimize social security payments. These rates are often high in Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, and as a result many employees are retained as contractors. While few state-owned companies have Russia-style obligations for the upkeep of social and economic infrastructure, over manning and inefficiencies are common.

Perhaps the most common defect emerging from due diligence is a shortage of management information. While accounting standards are international or convergent and reported information can generally be relied on, underinvestment in IT – and management procedures generally – means that management accounting figures taken for granted in more developed economies are often missing. In turn, this can lengthen the time spent on due diligence as managers and advisors dig for information they need to really understand the business. It also signals an area for early management attention when the acquisition is completed.

Valuation

In some of the bigger countries – Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary – vendor due diligence is beginning to emerge, making target evaluation easier. In smaller countries vendors may be less sophisticated, sometimes assuming due diligence will simply rubber stamp negotiated valuations, so expectations may have to be managed. Generally speaking, whatever the price, there are few outright bargains left in Central Eastern Europe as risk-reward profiles converge on those of the Western Europe. In middle market transactions there is little competition from global private equity funds and auctions are rare, but entrepreneurs – increasingly aware of the strategic value of their assets – are leaving little on the table. Most of the opportunistic deals were done well before accession. A similar process is in operation now, with bolder acquirers moving on from CEE to snap up companies in Romania and Bulgaria before they become EU members later in the decade.

Transaction integration

Valuations will obviously take into account the priorities of post-merger integration. As previously noted, underinvestment in IT and management processes is widespread. This is a pointer to perhaps the region’s biggest current handicap, the thinness of local management resources. Although the availability of skilled labor is one of CEE’s strengths, and in many countries there remain sizeable pools of unemployed, in certain locations there may be shortages, bidding up costs.

While general educational levels are good; CEE states need to continue investing in order to adapt educational systems to the realities of the knowledge economy. The workforce is on the whole flexible and well aware that the ability if necessary to run three shifts a day seven days a week is key to the region’s advantage. However companies should not make the mistake of concentrating so much on the deal that they underestimate the challenge of integrating and managing the target after acquisition. CEE companies often require more post-merger attention than Western European counterparts to deal with legacy system, labor and cultural issues.

Industry Sectors

Telecommunications

The telecoms sector accounted for several of Central Eastern Europe’s biggest deals in 2005, including the largest of all, the purchase of a 51 per cent state in the Czech Republic’s Cesky Telecom by Telefonica, for $3.6bn. The Cesky Telecom privatization leaves only the Slovenian Telekom Slovenije (due for privatization in 2007) of the region’s legacy fixed-line telecommunications companies still in public hands. It was accompanied by a number of smaller deals effectively consolidating the country’s alternate fixed-line operators into two substantial rivals to Telefonica 02 Czech Republic, as it is now called, the Russian-backed GTS and Ceske Radiokomunikace.

Fixed-line sectors in other CEE countries may see a similar pattern of activity in the next few years as they follow the Czech regulator’s example in unbundling the local loop to encourage new market entrants to compete with the national supplier.

Mobile operators were also at the forefront of deal activity in 2005. Poland’s Centertel (bought by TPSA) and Czech’s Oskar Mobil (Vodafone) changed hands in substantial transactions.

These deals may be the last for the time being in the CEE mobile sector, leaving most national operators in the hands of global players that will be in the market for the long term.

Investor interest in mobiles is already moving on to the next accession states: two mega-deals in 2005 saw Vodafone acquiring Romania’s MobiFon for some $2.5bn and Telekom Austria paying $2bn to take control of MobilTel of Bulgaria.

Energy

Central Eastern Europe is playing a full part in the wave of mergers and acquisitions sweeping through the global energy sector (oil, gas, refining and utilities). In Slovakia, Hungary, Czech Republic and Croatia energy transactions to a value of €11bn were effected from 2000 to 2004, with another €3bn in Romania. These totals reflect on the one hand governments’ varying willingness to use privatization and market liberalization programs to restructure and refinance their infrastructure projects, and on the other intense international competition for increasingly important strategic assets. Thus reports on the CEE energy sector show that it is being targeted not only by major Western European groups expanding eastwards (RWE, E.ON, Gaz de France) but also by Russian majors looking west (Gazprom, Rosneft and LUKOIL). At the same time, national champions such as the Czech power company CEZ, and oil firms MOL (Hungary) and PKN ORLEN (Poland) are also aggressively flexing their muscles as they compete for regional dominance.

With energy prices high and privatization programs having still some way to run, the sector is likely to remain active for the next few years – although outcomes are not always predictable since in most countries privatization and its timing remain politically contentious. For instance:

• Privatization of the increasingly active CEZ, still two-thirds owned by the Czech state, was cancelled after disagreement between government departments, although the authorities have allowed PKN ORLEN to complete the buyout of Czech petrochemical group Unipetrol;

• Having sold 25 per cent of Croatian oil company INA to Hungary’s MOL the Croatian government is debating whether to sell off a further tranche;

• Rumors abound over the sale of the Hungarian government’s remaining 12 per cent stake in MOL.

Three of Poland’s largest power plants for the time being are off limits to foreign investors, in order to create national champions, as plans to privatize energy assets run up against economic nationalism and strong workforce objections. Such energy privatizations as do take place in Poland in the near term will likely be via IPOs, dispersing ownership and allowing the state to retain a ‘golden share’.

The next wave of EU accession states has already begun liberalizing their energy sectors in anticipation of joining. This is particularly significant in the case of Romania, where energy is a large proportion of GDP.

Banking and Financial Services

In previously centrally planned economies, banking and financial service privatization plays a critical part in economic and structural reform by obliging countries to tackle head on issues of bad debts, non-performing loans and inherited close relationships with state-owned industries. Lacking initial banking experience, most CEE countries learned hard lessons during the 1990s, undergoing financial crises and sometimes painful restructuring and recapitalization before entering on a path of sustained banking expansion since the millennium. One result is a vibrant market-driven banking and financial services sector across the CEE. Another is rapid consolidation of national banking sectors as smaller institutions have been bought or exited. Third, in striking contrast to Western Europe, where cross-border deals have been rare, in all CEE countries except Slovenia foreign investors now dominate the market, sometimes overwhelmingly. Up to 80 per cent of the top banks of the region are in foreign hands, with Austrian, Italian, Belgian and French institutions predominant. Foreign banks have invested heavily and brought in expertise, IT, capital, innovation – and competition, leaving only a few examples of successful large domestically owned banks in the region. The most prominent, the Hungarian OTP, has been compelled to both acquire and pursue further regional acquisition targets, in light of growing competition and shrinking margins in its domestic Hungarian market.

Outside the six countries in this report, the recent €3.75bn purchase of a near-two-thirds stake in Romania’s state-owned BCR bank by the Austrian Erste Bank, a serial acquirer in the region, reflects continuing high investor interest in the sector over the whole area and caps a two-year period in which foreign companies have picked up CEE banking assets worth $13bn.

Mounting prices reflect high economic growth rates and the low penetration of financial services compared with Western Europe. Driven by competition, recent years have seen a credit boom, with credits extending into previously untouched areas such as retail (particularly mortgages) and lending to small businesses.

These factors mean that foreign interest in the sector is likely to remain strong, although with most of the initial privatizations in the area completed, attention will focus on further consolidation and expansion into the less developed geographies to the east and south. Indeed over the next decade a number of the regions recent acquirer’s may themselves become targets. International players with limited CEE presence – or those currently still sitting on the sidelines – may follow in the footsteps of UniCredit (acquiring significant CEE exposure via the HVB/Bank Austria-Creditanstalt) and target banking groups with established operations in CEE.

Private Equity

With the exception of Poland, home to around 60 per cent of the region’s $4bn private equity investment, PE has historically played a limited role in CEE countries. This is a consequence of the region’s higher perceived risk, small population of mid-sized companies capable of attracting the big global funds and lack of confidence in engineering exits. This may now be now changing. Accession and subsequent rapid integration into the EU have alerted investors to the region’s growth rates and increased comfort levels, while a series of successful exits has enabled private equity funds to raise cash for larger deals. At the same time, the disadvantage of relatively undeveloped capital markets is at least partially offset by the lack of competition for deals and their consequent ‘fair’ pricing.

The European Private Equity & Venture Capital Association estimates that some €496m was raised by fund management teams for investment in Central Eastern Europe in 2004, with interest centered on IT and media, real estate, food processing, tourism, retail and others. Several large exits in 2005 gave a boost to fundraising: Mid Europa Partners, formerly known as EMP Europe, raised €650m for its Emerging Europe Convergence Fund, and Advent International raised €330m, its third for the region. The most successful private equity exits of 2005 were in mobile telecoms, typically trade sales to inbound investors, with high returns. EBRD, the largest investor in CEE funds, estimates that returns in 2005 were in the mid-20 per cent range.

Clearly leading the way in CEE private equity is Poland, with half the region’s population and GDP and by far the most vigorous stock exchange. Poland is the only CEE market with a record of successful IPOs. Private equity in Poland has so far concentrated on telecoms and media, with manufacturing sectors running behind. A long way behind Poland in private equity terms come Hungary and the Czech Republic, held back by the lack of large opportunities rather than availability of funds. On the fringes of the region, Bulgaria is a star performer, with private equity investments accounting for around 1 per cent of GDP, one of the best ratios in Europe, and Romania is also promising. As the region continues to develop, the role of private equity is set to increase sharply from today’s relatively modest levels.

In Summary

EU enlargement in 2004 has brought the attractions of Central Eastern Europe for international investors into sharp focus. It is clear that having put the difficult early years of transition behind them, for many investors the region is going through something of a golden age, offering stability and geographical proximity to old Europe on the one hand together with low wage costs and convincingly faster rates of growth and economic development on the other: ‘Europe plus’, as it has been called.

Except for privatizations, now tailing off, the business of doing deals is quicker, more transparent and less bureaucratic than in many rival investment destinations. Since accession, competition for FDI has if anything intensified, bringing pressure on all the governments of the region to speed up liberalization, cut red tape and make regimes more business friendly. Slovakia’s spectacular success in simultaneously simplifying and cutting tax rates while increasing the overall revenue for the state may be a pointer to the future.

On the transaction front, although in many industries, including retail, telecoms, banking and financial services and consumer products, the main market positions are by now well marked out, there is still generous scope for regional consolidation and expansion.

A few remaining privatizations in energy and utilities add to deal prospects. Less developed capital markets (except in Poland) limit the possibility of IPO exits, but a number of recent successful trade sales have given a boost to private equity activity in the region.

For the future, public-private partnerships (PPPs) are still in their infancy, but pressing transport and power infrastructure, healthcare and education needs in many parts of the region will generate large needs for investment capital. The imminent accession to the EU of countries such as Romania and Bulgaria will continue to push Europe’s economic center of gravity eastward. We believe for all these reasons Central Eastern Europe will justifiably remain high on dealmakers’ ‘to do’ lists for the next few years. Through our Ernst & Young offices in the region we look forward to helping them to benefit from its unique opportunities. (Data in this report has been sourced from IntelliNews, OECD, Bureau DijkVan , the World Bank, and other business news sources.)

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter