Publications Capturing Value From M&A In Upstream Oil & Gas

- Publications

Capturing Value From M&A In Upstream Oil & Gas

- Christopher Kummer

SHARE:

By Christopher Handscomb, Emily Sheeren, Jannik Woxholth – McKinsey & Company

Contributors: Scott Nyquist, Joe Quoyeser

Successful M&A requires both a solid strategy and excellence in integration planning and execution.

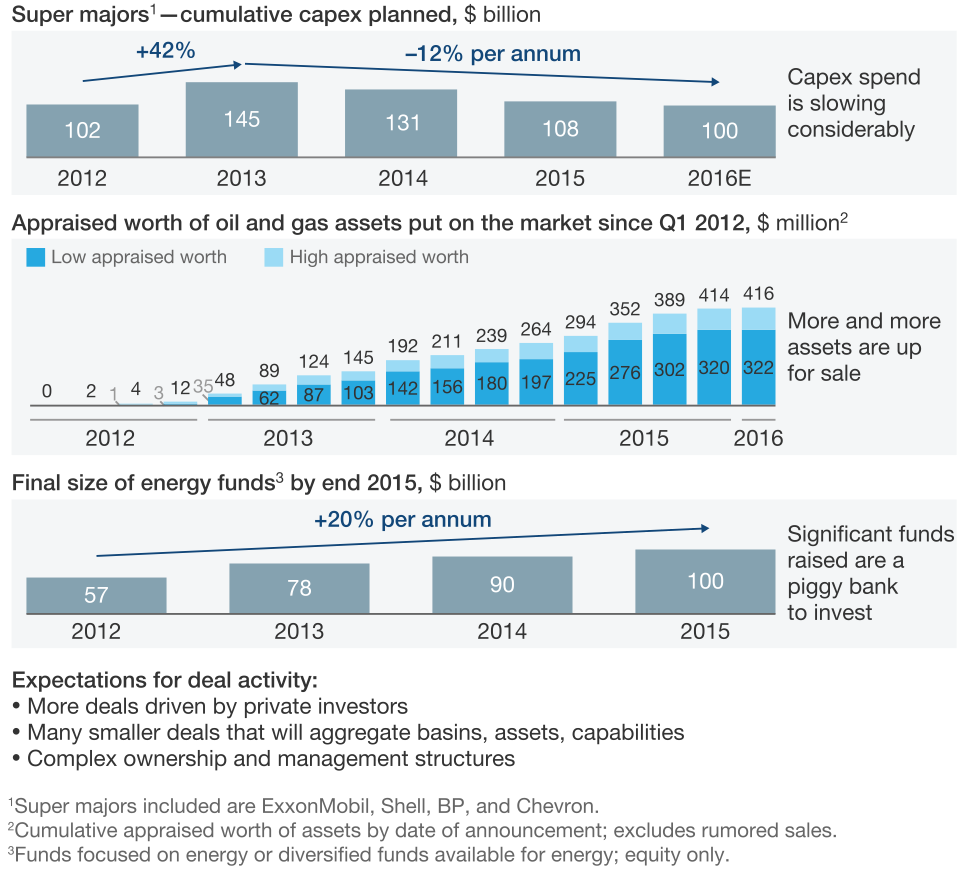

The collapse in oil price has begun to trigger consolidation in the oil & gas industry, with six large-scale deals already executed. Given stalling cash flows, looming bankruptcies, shrinking capex budgets, and the tremendous war-chests raised by private equity, we expect to see a dynamic M&A environment that fosters creative deal-making—especially for independents and small to midsized entities (Exhibit 1). Getting value out of M&A at this point in the downturn will require not only a solid strategy, but also flawless planning and execution of integration.

Integration will be particularly challenging for deals in this industry, at this point in time, for a variety of reasons. Many entities have already taken headcount reductions — making “quick win” synergies less apparent. Also, the distributed nature of field operations makes it challenging to capture economies of scale from M&A that are typically seen in other industries.

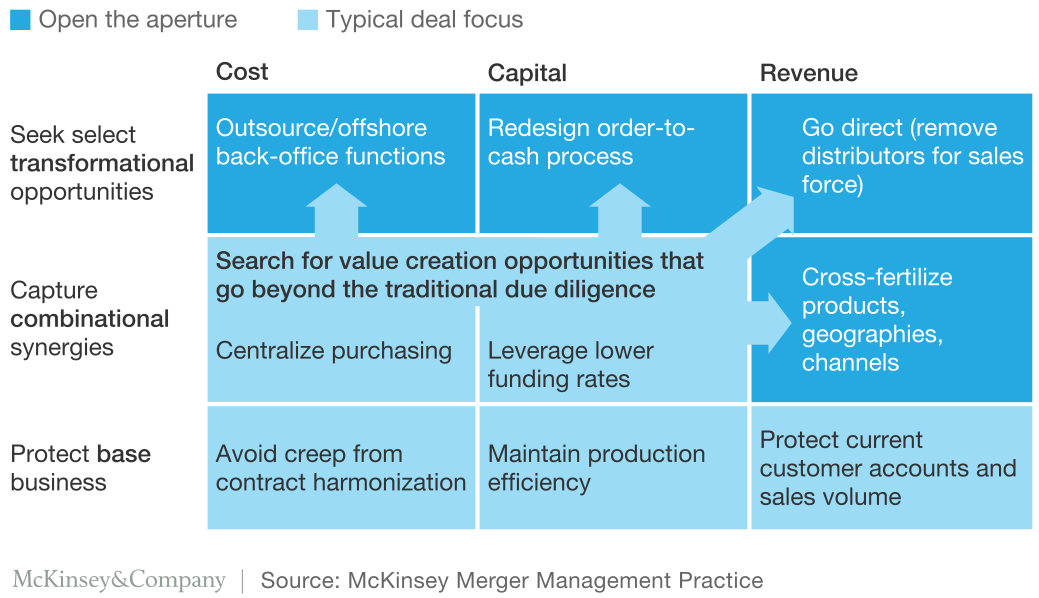

Despite these challenges, we believe there is still significant value that can be captured — particularly from looking beyond traditional synergies (Exhibit 2). The value at stake and approach to value capture varies across deal types, and deal-makers should consider lessons from all three:

- Asset deals and roll-ups: Bolt-on asset acquisitions by majors, NOCs, or independents; or roll-ups of multiple assets into new entities

- Majors or NOCs buying independents: Large-scale acquisition of independent players (e.g., Shell-BG)

- Merger of equals: Merger between similar-sized independents or independent and NOC

Exhibit 1. We are on the brink of an industry consolidation.

Exhibit 2. Look beyond due diligence; open the aperture to exceed traditional synergies.

Asset deals and roll-ups

Despite the distributed field operations in upstream oil & gas, asset deals can still drive significant value from consolidation that unlocks economies of scale within basins. A prime recent example is Chevron’s purchase of a stake in BP’s Paleogene deepwater GOM projects, which allows the companies to develop the fields with fewer hubs and with a single operator.

Based on our experience, we see three primary value levers from asset deals:

1. Infrastructure consolidation. Examples include water and sand optimization in shale operations and optimization of rig schedules or helicopter and vessel “milk runs” in the offshore sector.

2. Organizational consolidation. For example, reducing layers in the organizational structure for field operations by sharing roles across multiple assets. This can both increase workforce utilization and facilitate sharing of best practices.

3. Procurement consolidation. Here, we see value from optimizing supplier mix and contracting strategy—where agreements are often triggered for renegotiation when ownership changes—and engaging with suppliers on how to improve efficiency within a basin.

To unlock the full value from an asset acquisition, establish a clean team—early—that can design the new in-basin operating model with full access to information from both companies. This is particularly important with regards to procurement—where clean teams can identify opportunities and have them “ready to act on” when the deal closes to accelerate value capture. Do also utilize the clean team to dig deeper into operations at both companies before close and, if the acquisition is part of a roll-up or a long-term basin strategy, plan beyond the current deal as you develop your post-close operating model.

Securing the right New Co. leadership is critical to a successful basin consolidation and deserves significant investment of time and energy. Because most leaders in these assets have been rewarded purely for growth and adding new barrels, it may be challenging to assemble a team who can perform in today’s context. Our experience shows that looking beyond the current top team—often to top performers at lower levels—may help uncover leaders who can deliver performance.

Majors or NOCs buying independents

These deals typically create value from overhead cost reductions and benefits from bringing together complementary portfolios. Shell-BG is a recent example, where BG’s deepwater Brazil assets and its significant LNG portfolio provide new reserves and business opportunities for Shell.

While these synergies are typical and fairly obvious, value from bringing together complementary capabilities is often overlooked. At an aggregate level, this falls in two categories:

1. Apply a stable backbone of process rigor to target portfolio. Delivering on megaprojects is a core capability of the majors, while independents that have grown out of success in exploration and business development often lack the capabilities required to ride the next wave of value creation. The value potential grows with size and complexity of the target portfolio, with BG’s deepwater Brazil assets making a prime example.

2. Transfer dynamic capabilities from target operating model. Similarly, independents typically bring dynamic capabilities such as lean, value-focused organizations with fast decision making. This means lower cost, more pragmatic use of supplier market and increased ability to capture business opportunities—all critical success factors in today’s fast-changing, low oil price environment.

Combining the two sets of capabilities would create the ultimate agile oilco, and it is of course hard to achieve. Still, an acquisition gives you the ultimate opportunity to take steps in this direction by selectively deploying organizational practices across the merged entity.

This requires true willingness to learn from the target and excitement about having “open book” access to data and people at a former competitor. You must quickly establish an unbiased and open-minded team that draws on data and experience from both parties. The team should apply a combination of “hard” quantitative benchmarking of the two companies, with “soft” qualitative elements such as performance reviews and other management practices.

Moreover, implementation requires top-down push along with pull from the relevant business units. Senior leadership must decide where to selectively deploy process rigor and specific dynamic capabilities respectively, and you need strong commitment from the top to drive through a holistic change program.

Mergers of equals

Mergers with truly equal parties are of course rare, but combinations of two fairly equally sized companies are not uncommon. Repsol’s acquisition of Talisman provides a recent example, along with several of the big deals from the 1990s. For these cases, three buckets of levers stand out with large potential that is often overseen or at least not fully captured.

1. Portfolio high-grading. Increased optionality from combining portfolios automatically unlocks new opportunities. With the right data and insights, significant value can be created through strategic post-deal investments, divestments, and asset swaps—enabling more opportunities of the type already addressed under “asset deals” above.

2. More efficient capital allocation. We often see mergers where one company is overinvesting while the other has more attractive opportunities. Yet companies fail to realize the potential. For example, in one merger we know, the parties still can’t agree on a centralized capital allocation process, years after the deal closed.

3. Improved organizational effectiveness. Larger organizations allow for more specialization, which drives functional excellence. Consolidating corporate functions alone often delivers 30 percent or more savings along with improved service quality. Larger talent pools and increased variety of internal job opportunities help to find the right people for the right job. This further improves talent retention, along with leadership development through exposure to a more varied set of business challenges.

All this requires a combination of fast and coordinated decision making, which is particularly difficult in a merger setting where both companies are of similar size, and no one leadership team is initially accepted to assert true authority.

To succeed, a designated team must be provided with all necessary data and resources, and be left to build the new portfolio and organization. To ensure talent retention, communicate early, clearly, and convincingly to the people you want to keep, and “walk the talk” by openly appointing leaders from both companies to New Co. positions.

TAGS:

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter