Introduction

One of the first merger-and-acquisition (M&A) transactions in China was completed in 1985, barely seven years after Deng Xiaoping started opening communist China to the world. It was the purchase by Singapore’s Hong Leong Enterprises, for an undisclosed sum, of Rheem (Far East), a maker of steel drums established in pre-communist 1946 China by Rheem International USA. Hong Leong upgraded Rheem’s facilities and injected its businesses into its China unit, which today owns 15 plants that churn out steel drums and pails, plastic bottles, jerry cans and other plastic and steel containers.

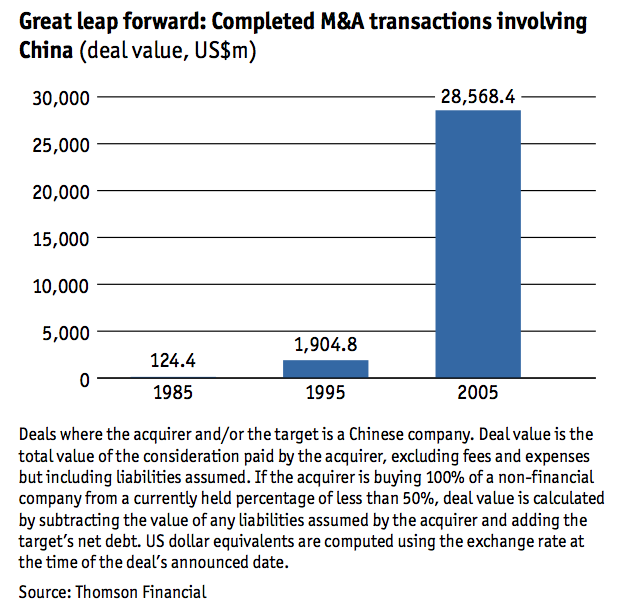

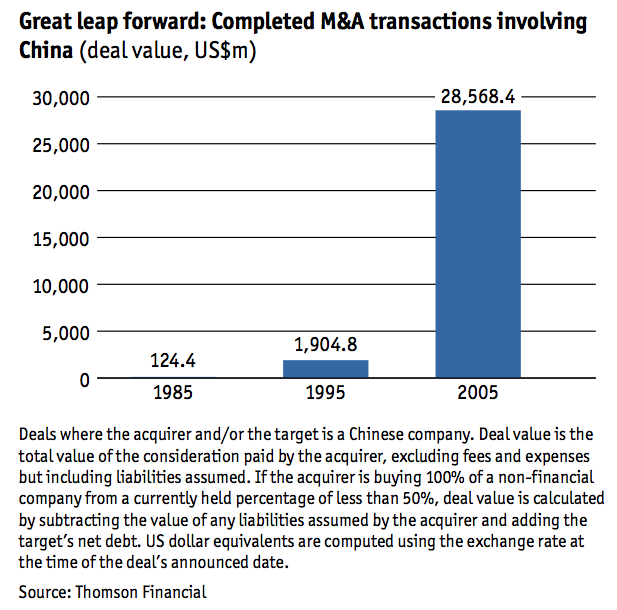

Fast forward 20 years to 2005. The world was stunned by news that US icon IBM, a company synonymous with personal computers (PCs), was selling its PC business for U$1.75bn in cash and assumed debt—to China’s Lenovo Group. It was a great leap forward from the humble steel drum to the IBM ThinkPad. As tracked by global data provider Thomson Financial, completed M&A deals involving China totalled just US$124m in 1985. The tally jumped to US$1.9bn in 1995, and to a record-breaking US$28.5bn last year, making China the largest M&A Asia-Pacific market after Japan and Australia. China passed South Korea for the No 3 spot in 2002.

How will China’s rise as both M&A target and acquirer affect domestic, regional and global businesses? What opportunities await acquiring companies? How can they avoid the inevitable pitfalls? Which mainland industries are ripe for consolidation at this time and which ones look ready for the picking going forward? Conversely, what are the foreign assets that are attracting the attention of emerging Chinese multinationals? And what about the morning after? With the frenzy of deal making behind them, how can companies increase the chances of success for their new acquisitions?

This white paper aims to answer those questions through a survey of 231 companies in China and the rest of the world on their M&A intentions, activities and experiences. We also conducted in-depth interviews with acquired companies, those that did the acquiring, Chinese regulators, investment bankers, management consultants, private-equity investors, lawyers, academics and others engaged in the M&A process. The data and insights gleaned are set forth in five chapters.

Chapter 1 The playing field takes a macro look at M&A in China, at the economic, regulatory and business drivers within and without the country that are influencing the trend, and the key sectors experiencing M&A activity.

Chapter 2 Who are the players? focuses on the M&A dramatis personae, including multinational companies, private-equity firms and other foreign enterprises seeking to buy a piece of China, and the eme rging Chinese transnationals that are starting to acquire companies and assets abroad.

Chapter 3 On the ground: survey results forms the heart of this white paper and is the chapter where we analyse the findings.

Chapter 4 Operational issues is devoted to the M&A process, looking at among other topics, due diligence, valuation, regulatory approvals and post-merger integration.

Outlook: The way forward is the concluding section that outlines what lies ahead for M&A in China. The current trend of rising M&A activity will continue gathering strength in the foreseeable future as China overtakes Germany to become the world’s third-largest economy.

(Last year, China surged past France, the UK and Italy to claim the No 4 slot.) The other key M&A drivers include China’s fulfilment of its pledges to the World Trade Organisation to fully open to foreigners its financial, telecommunications, retail and other service industries, and the growing maturity and sophistication of domestic Chinese enterprises.

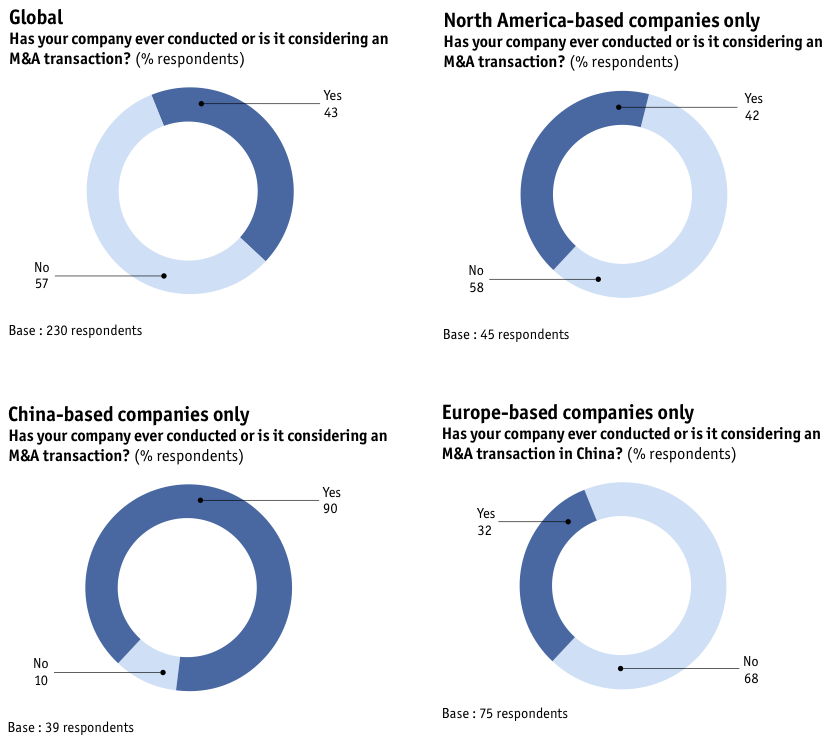

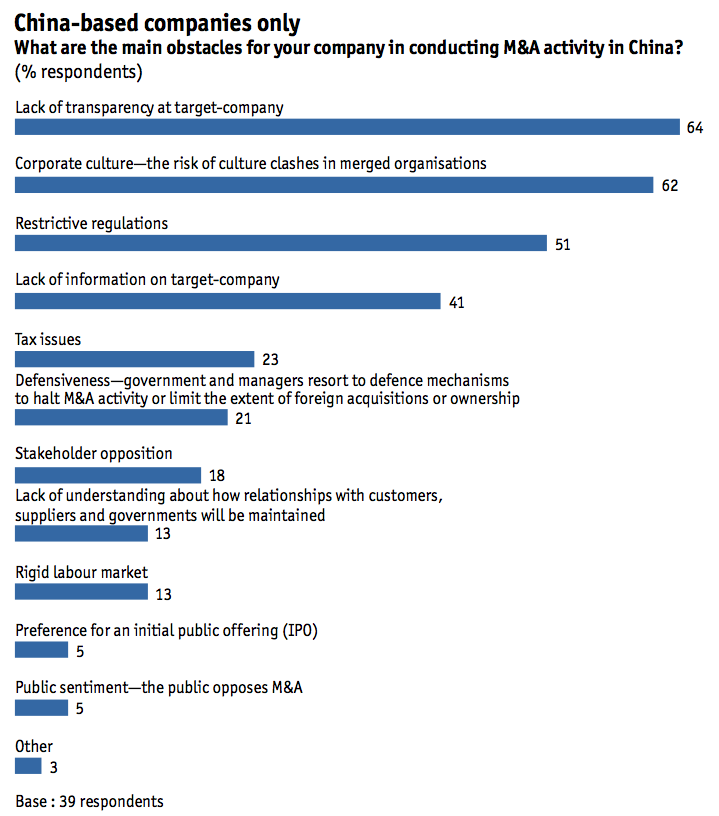

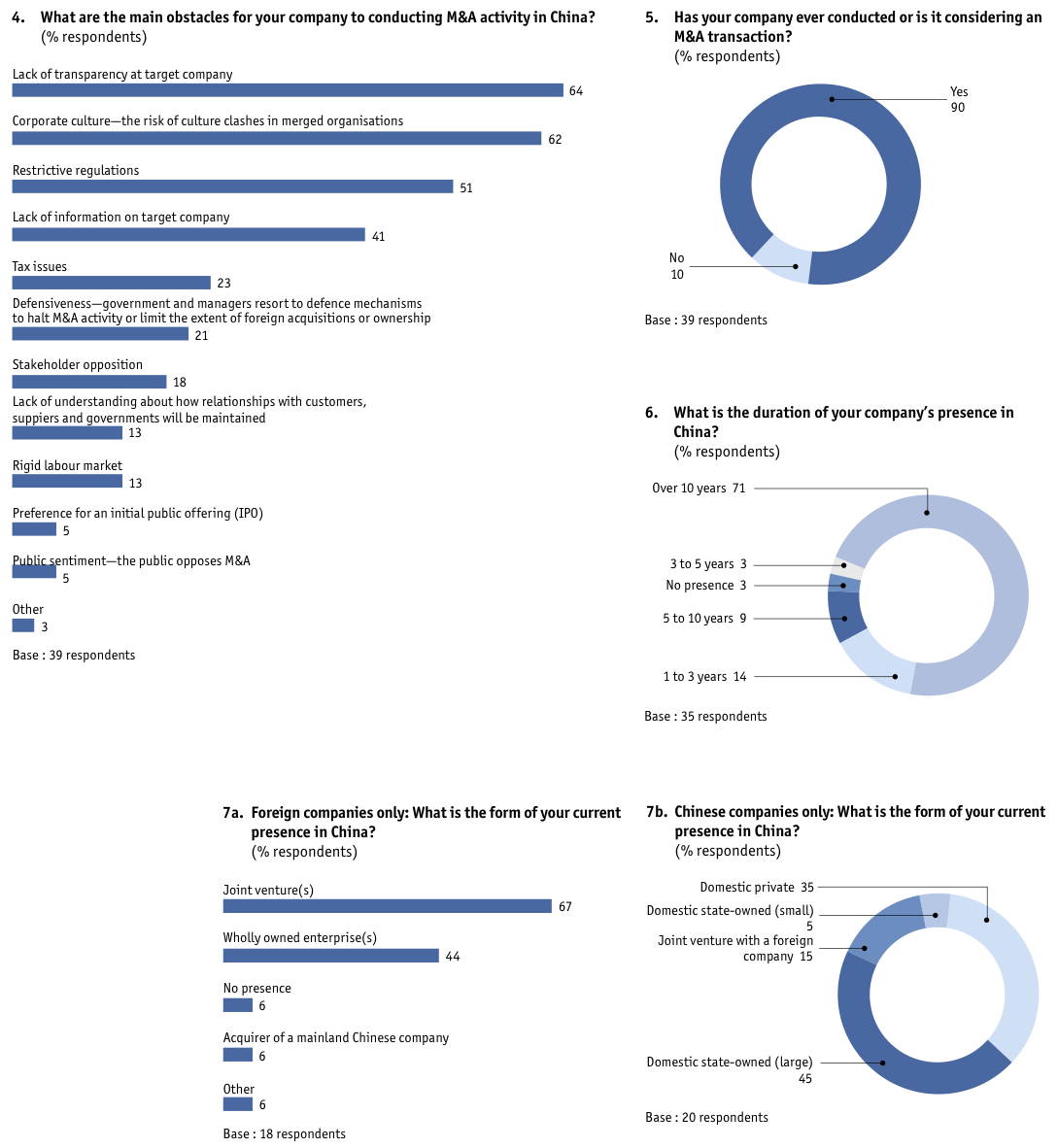

This expectation is consistent with the Economist Intelligence Unit’s survey results. Four out of ten respondents globally say their company has conducted or is considering an M&A transaction in China. Domestic Chinese companies are even more aggressive, with nine out of ten saying that they have participated or intend to participate in an M&A. This is not to say that everything will go smoothly: 64% of global respondents worry about lack of transparency at a target-company, 61% about the risk of culture clashes in the merged organisation, and 51% about China’s restrictive regulations.

They have reason to be wary. In a report to be released in April 2006, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) lauded China for streamlining project approval procedures and promulgating landmark legislation on cross-border M&A in 2003. But the OECD still judges the regulatory framework “fragmentary, over-complex and incomplete,” and notes that “foreign ownership restrictions persist and are not wholly transparent.” The report recommends a number of policy responses, among them further easing of foreign-ownership restrictions, adoption of best-practice and transparent merger notification procedures, more improvement in corporate governance, and full opening of capital markets to foreign investment.

While the government grapples with these complicated issues, foreign and domestic businesses appear to be increasingly willing to take their chances with the imperfect M&A rules. China and the rest of the world are simply moving too fast. It is clear that M&A and the industry consolidation it brings would soon become a significant part of China’s business landscape. The farsighted enterprise, whether a multinational or a Chinese company, would do well to take this into account in conducting its business today and in planning for tomorrow.

Executive summary

For many investors, China is a land of limitless opportunity. There, they can sell their goods and services, feed their supply chain, invest in companies—or buy them out. The first merger-and-acquisition (M&A) transaction was completed in China in 1985, and since then the country has become a prominent target and a prolific acquirer. Completed M&A deals involving China totalled a mere US$124m in 1985. Two decades later, that figure has soared to US$28.5bn, and China has dislodged South Korea as the third-largest M&A market in Asia after Japan and Australia.

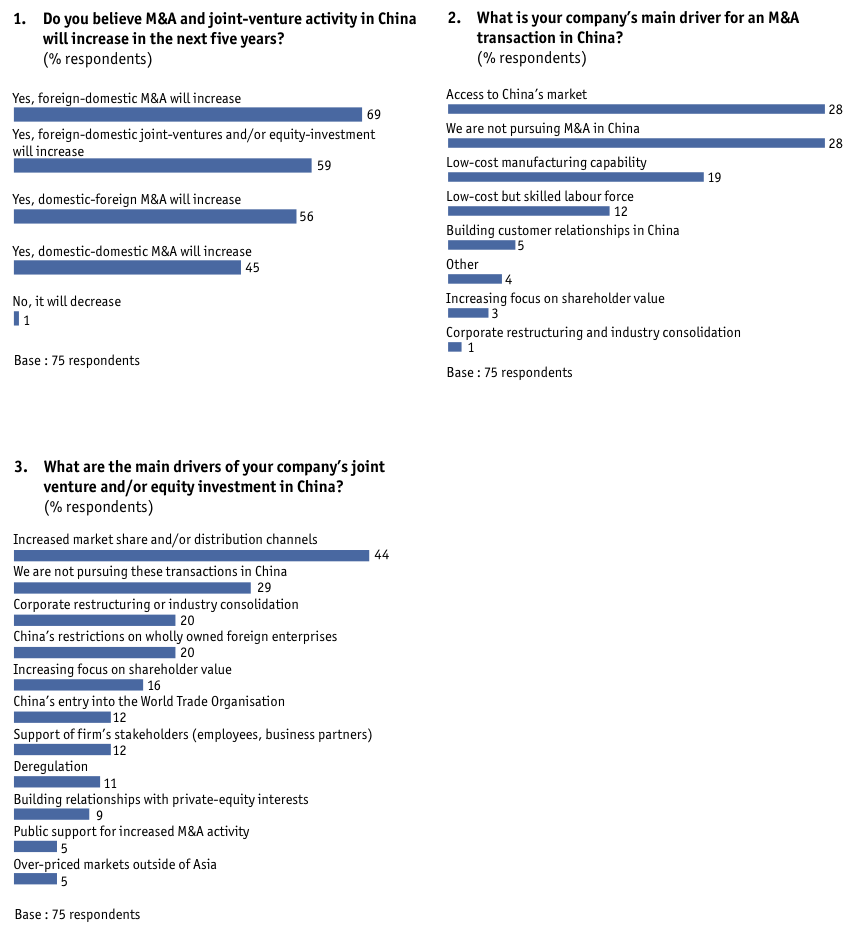

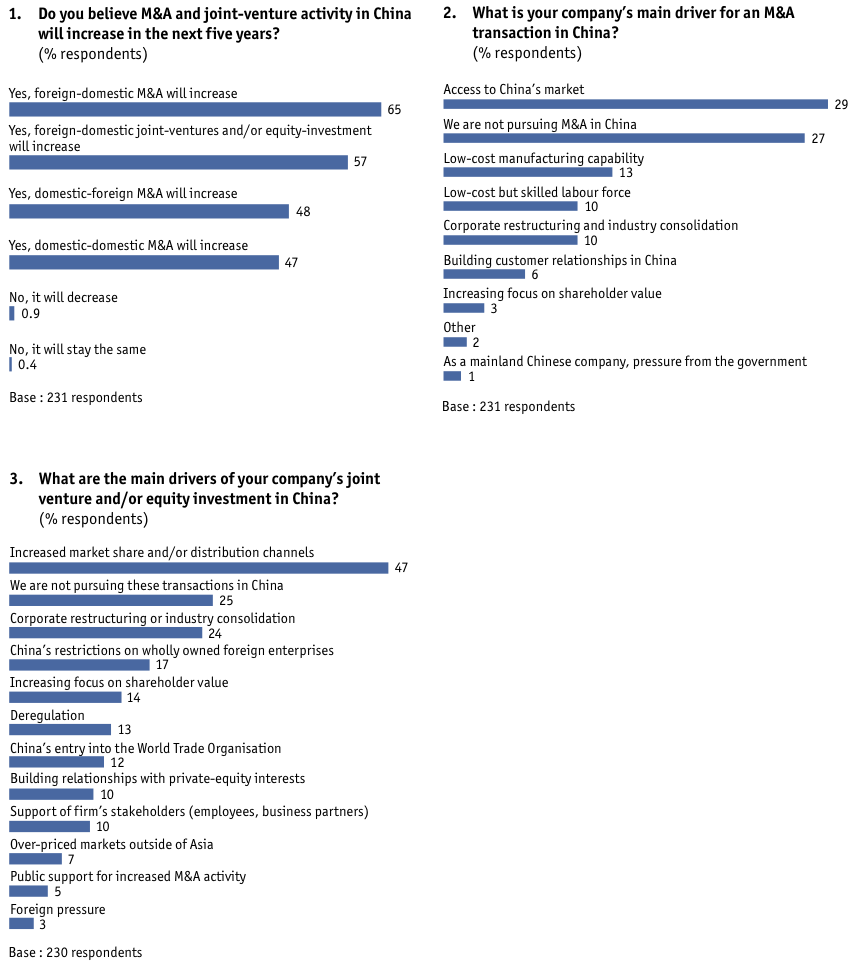

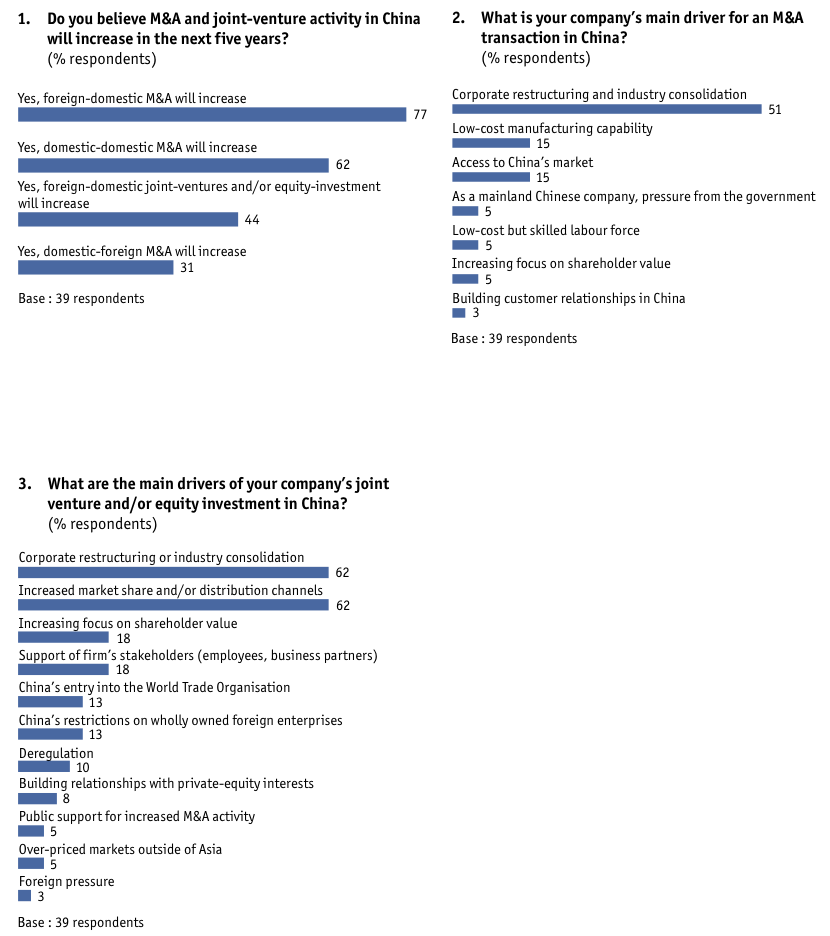

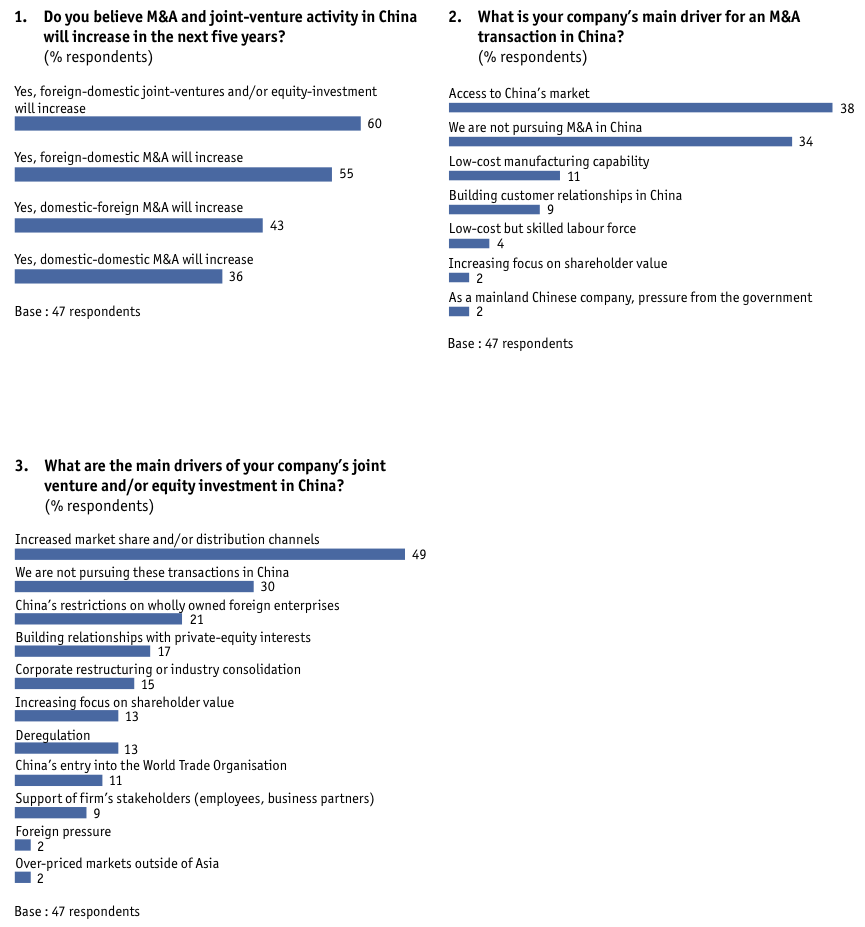

Will this frenetic M&A activity continue in China? Absolutely, says The great buy-out: M&A in China, a new report by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), sponsored by Ernst & Young, Mercer Human Resource Consulting and Morgan Stanley. M&A activity will maintain its sizzling pace, with foreign-domestic transactions rising over the next five years, according to 65% of respondents to a global survey of 231 executives. About half of respondents also believe that in the same period there will be an increase in domestic-foreign, and domestic-domestic, M&A transactions. China-based respondents were even more positive about domestic-domestic M&A in China—six out of ten expect it to climb even higher.

The report, which is based on the survey results and interviews with local and foreign companies, as well as government agencies, lawyers, consultants and other M&A professionals, suggests that the main reasons for the acceleration are the rise in purchasing power and private consumption in China, and the government’s desire for foreign funds and expertise for its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as it opens sectors of the economy to foreign competition. A more relaxed regulatory regime also has expanded the scope and geographical reach of wholly owned foreign enterprises. Underpinning many of these drivers is China’s commitment to liberalise its economy on its entry into the World Trade Organisation in 2001.

Other main findings of The great buy-out: M&A in China include:

• Many foreign companies are making limited M&A forays into China. The reasons are to get a feel of the process and learn the ways of the local competition in anticipation of the economy being opened fully. Domestic private-sector companies are being propelled by the same imperative, often upon the prodding of private-equity investors.

• Domestic demand is leading to the creation of local private companies, which often become M&A targets. Surging domestic demand has led to the emergence of hundreds of thousands of local private-sector firms that are competing with state-owned companies. Sino-foreign joint ventures, which in the early years focused on China as a cheap source of labour to make goods for export, are now targeting Chinese consumers themselves.

• The sector of choice in foreign-domestic M&A last year was finance. This sector, particularly the banks, attracted US$9.7bn in completed acquisitions—not surprising, given the Chinese government’s focus on strengthening the fragile financial system and the scheduled further deregulation of the banking industry. At a distant second was high technology, including computers, followed by industrials. In domestic-domestic M&A, the hottest sectors last year were industrials, energy and power, materials, high technology and real estate. The deals tended to cluster around state-owned companies purchasing their own subsidiaries or each other. In domestic-foreign M&A, energy and power accounted for 46% of all outward investments in 2005, with high technology coming second at 33%.

• Foreigners, primarily from the US and Europe, are the main acquirers of Chinese assets. They fall under two broad categories. The first category comprises strategic investors, which are operating companies buying other businesses to expand or defend market share and enhance profitability. Among the foreign companies that made the biggest M&A waves in China in 2005: Bank of America, HSBC, Royal Bank of Scotland and Goldman Sachs. The second category comprises private-equity investors, which buy minority stakes in start-ups, mid-growth enterprises and mature businesses. They use funds pooled from individual investors, with the aim of eventually selling out at a profit through such exits as an initial public offering or a sale to strategic investors.

• Chinese private-sector companies are the most interesting targets. Most of these are still too small to interest foreign strategic investors, but they are attractive to private-equity investors and to larger Chinese companies. There are three other categories of targets for foreign (and some domestic) acquirers: SOEs that are under pressure from the central government to consolidate as China allows foreigners into their industries (including iron and steel, automobiles and financial services); money-losing SOEs selling off non-core assets or whole operations; and state enterprises set up to build and operate infrastructure facilities such as toll roads that are now selling off concessions.

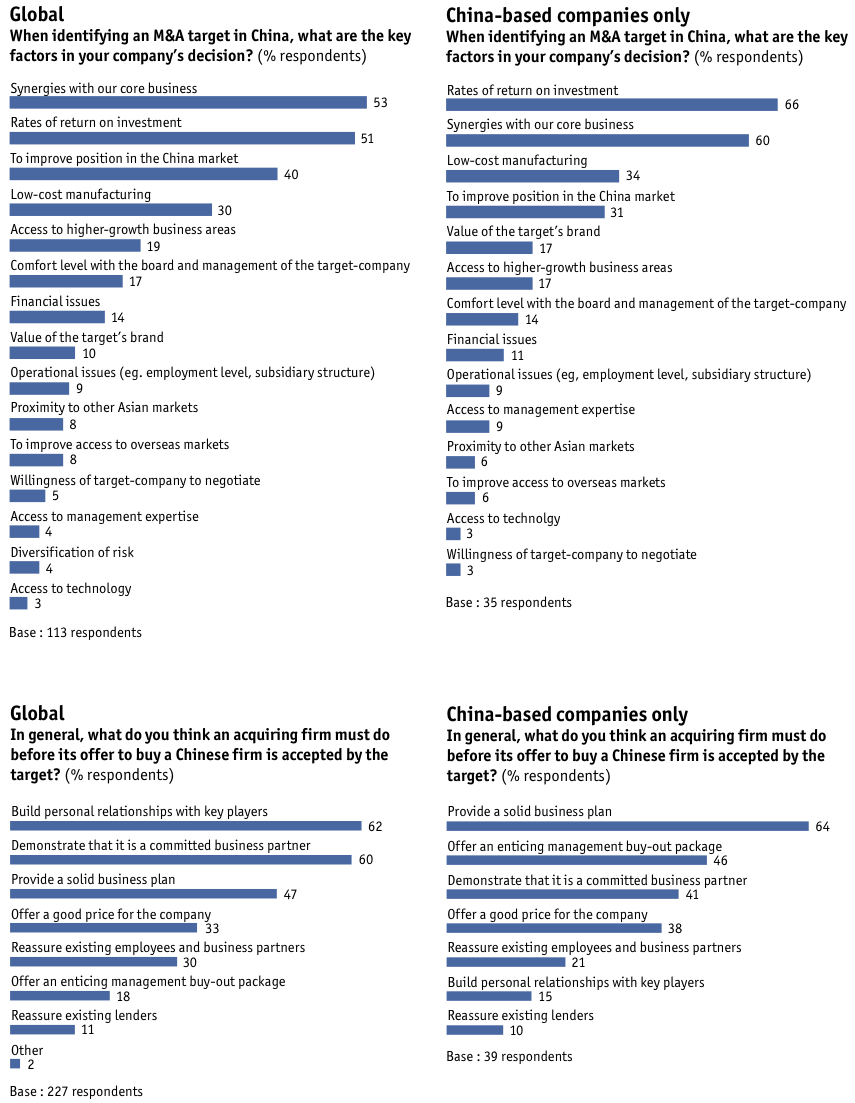

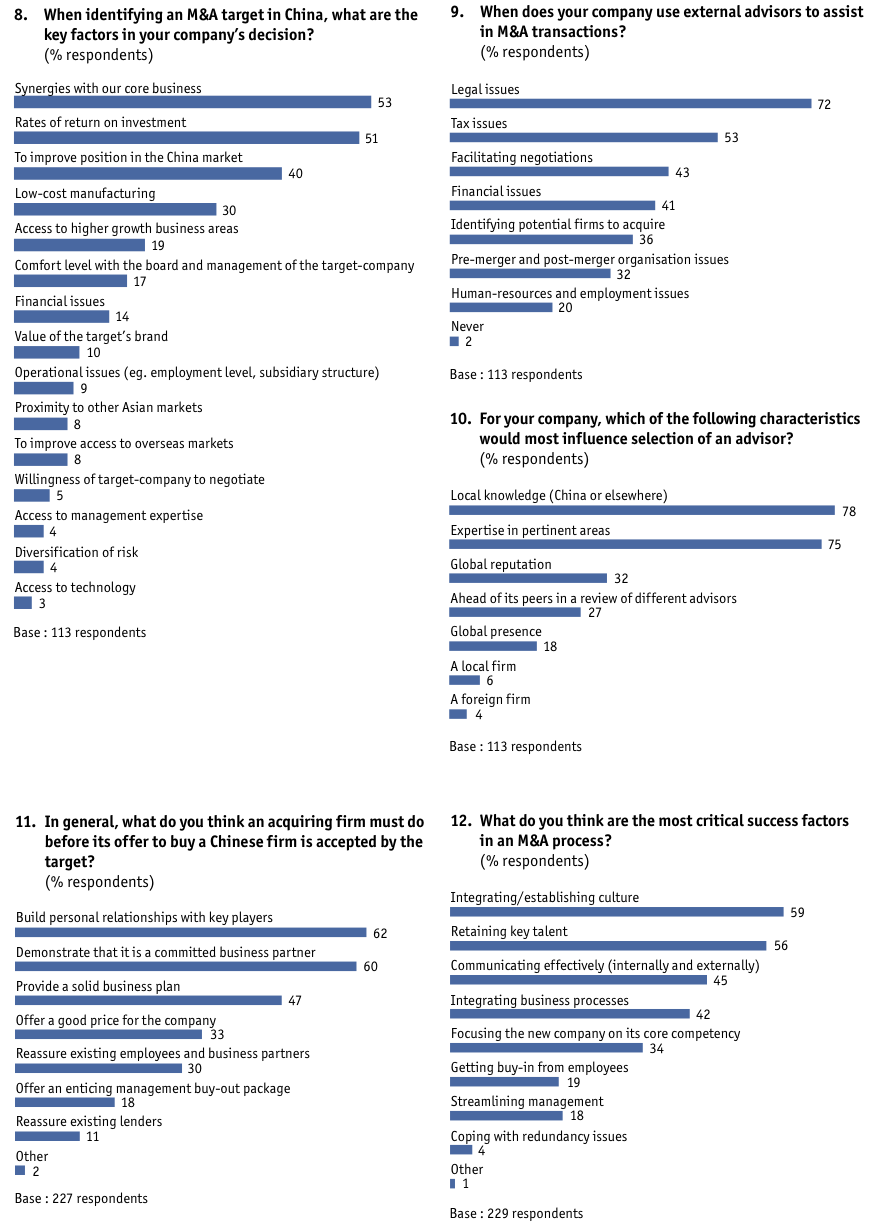

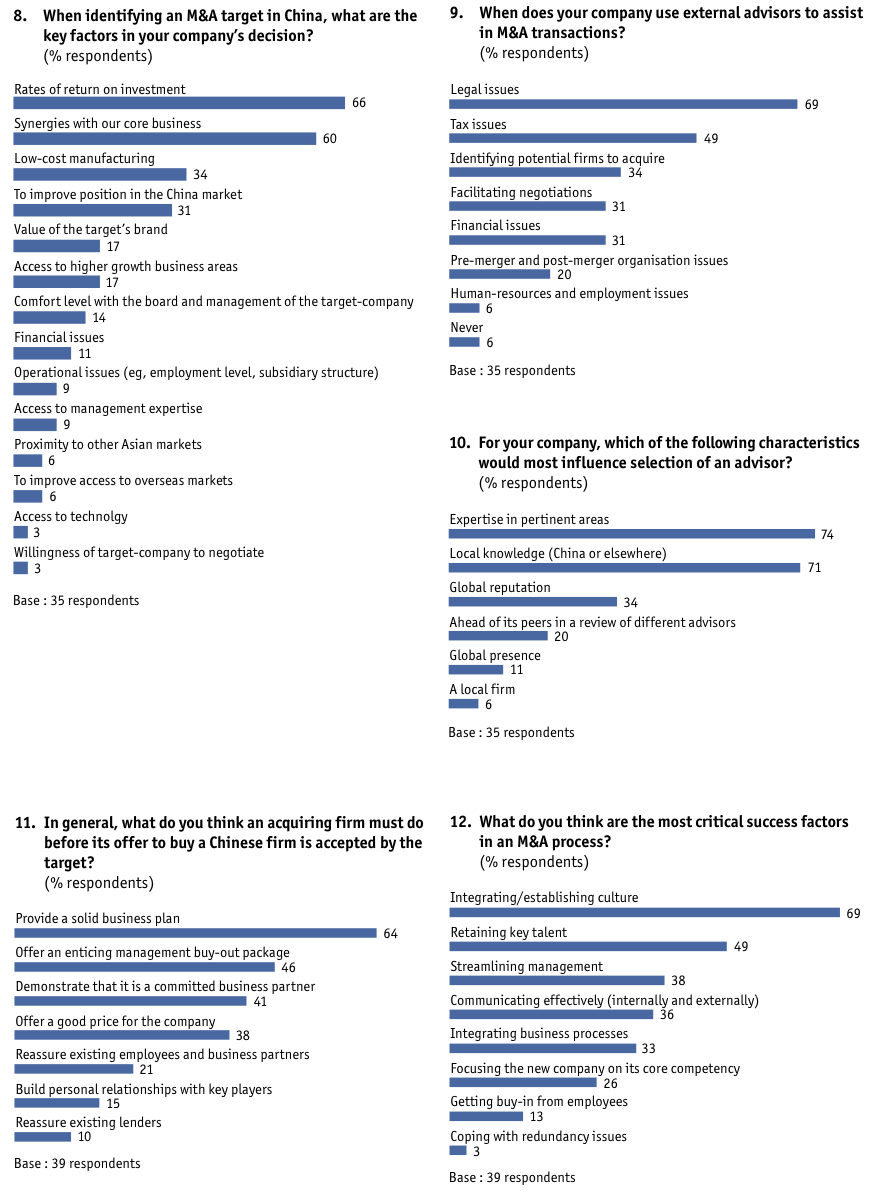

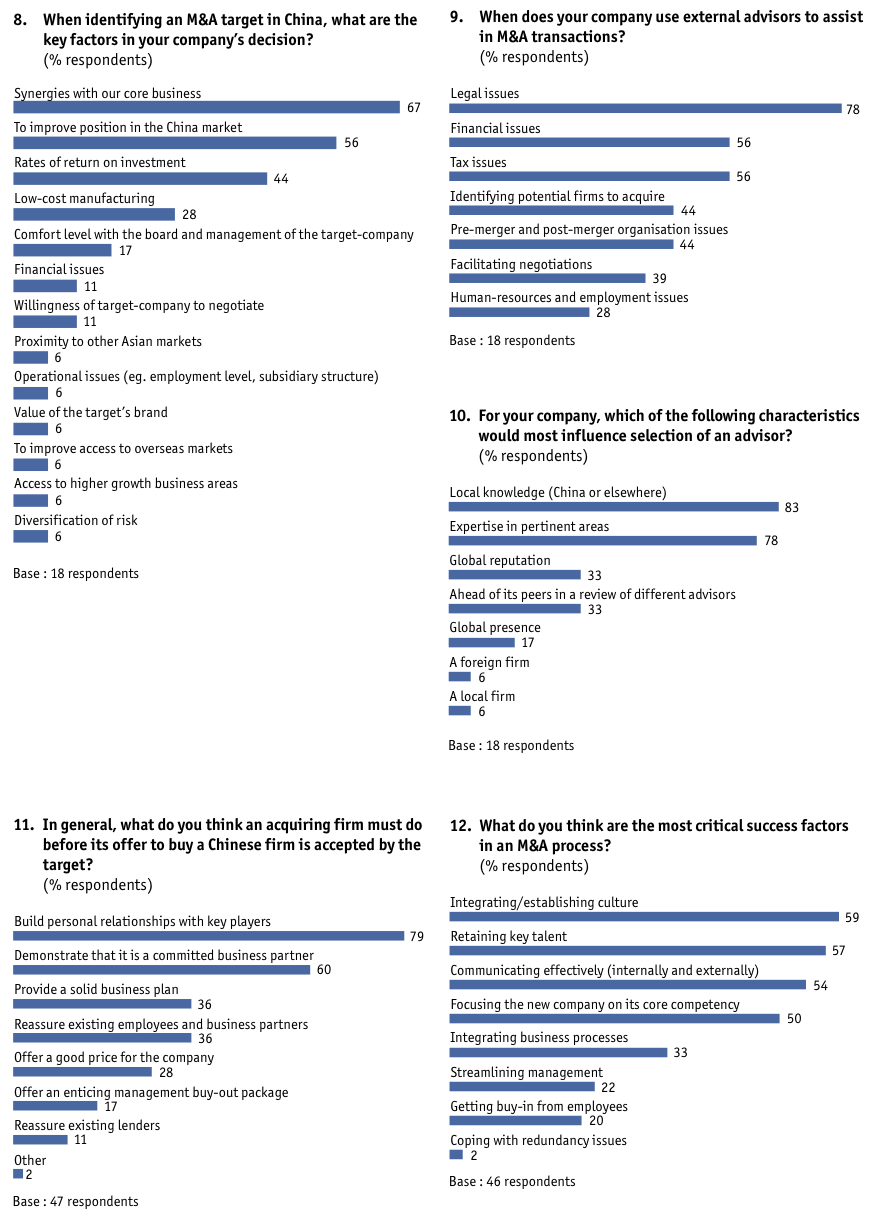

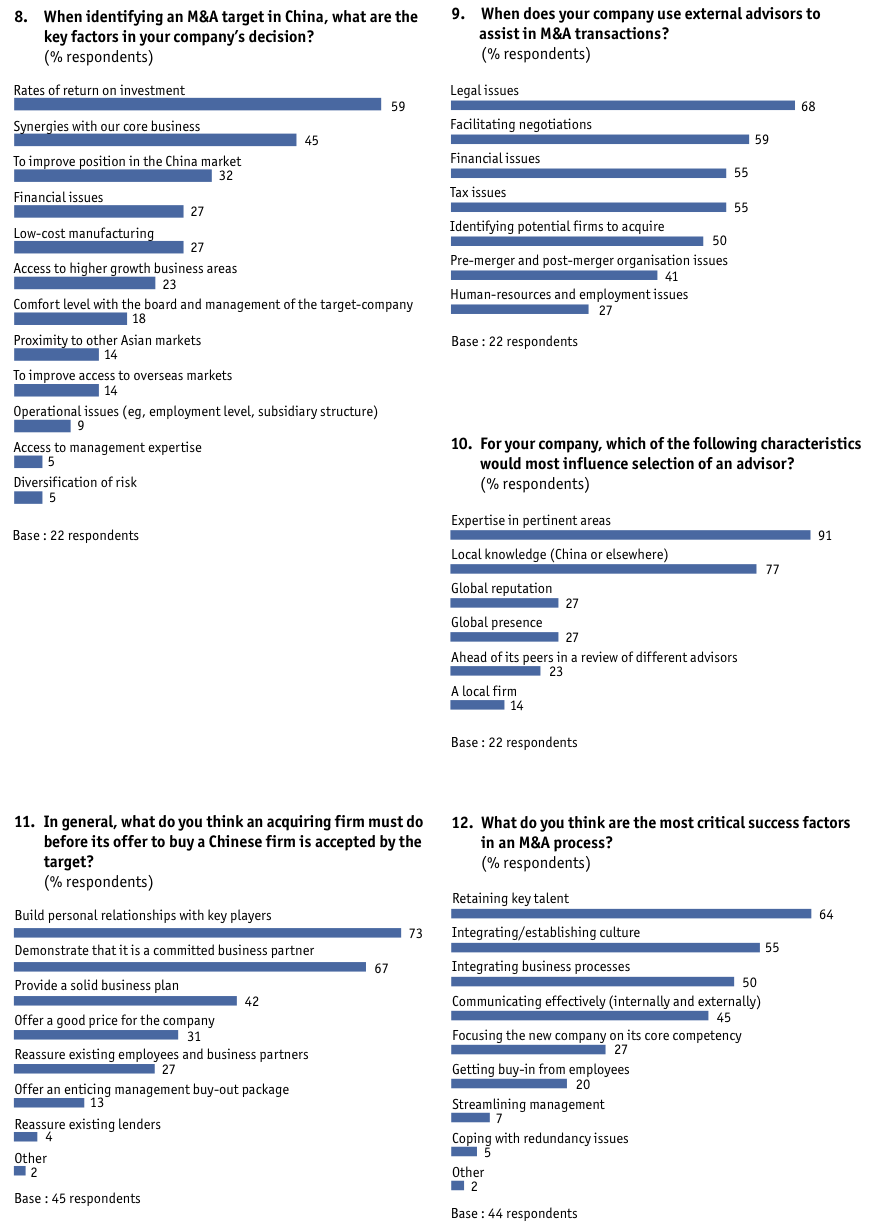

• Synergies with their core business and rates of return on investment are the main attributes in targets. Half of respondents to the global survey believe these are the key factors when identifying targets. Four of ten (40%) also cite the prospect of the target-company improving their firms’ position in the China market. Respondents in the China-only segment of the survey also identify synergies and rates of return as important factors, but 34% of them also point to low-cost manufacturing as a factor for considering a company for acquisition.

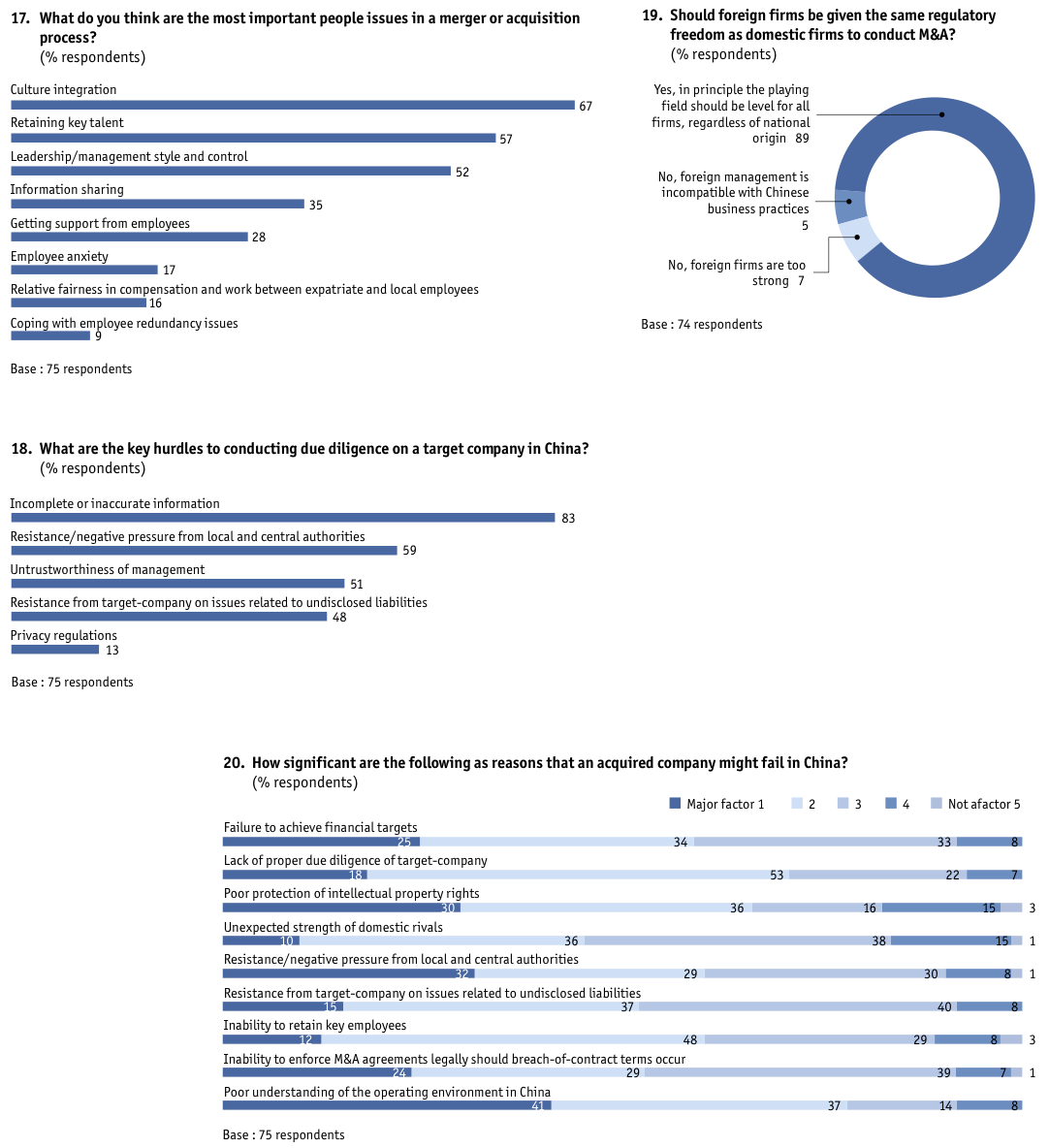

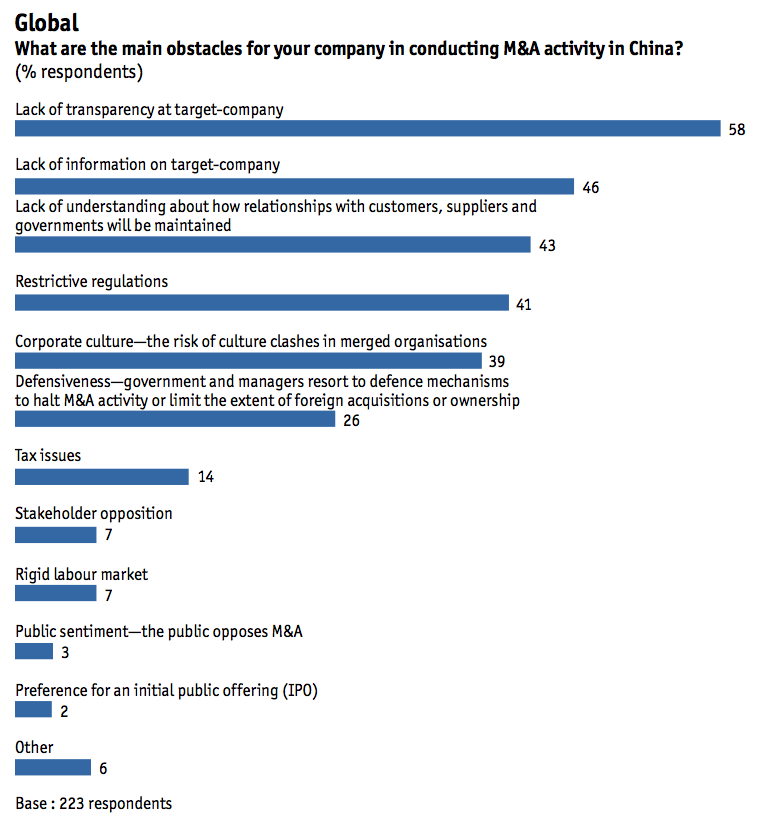

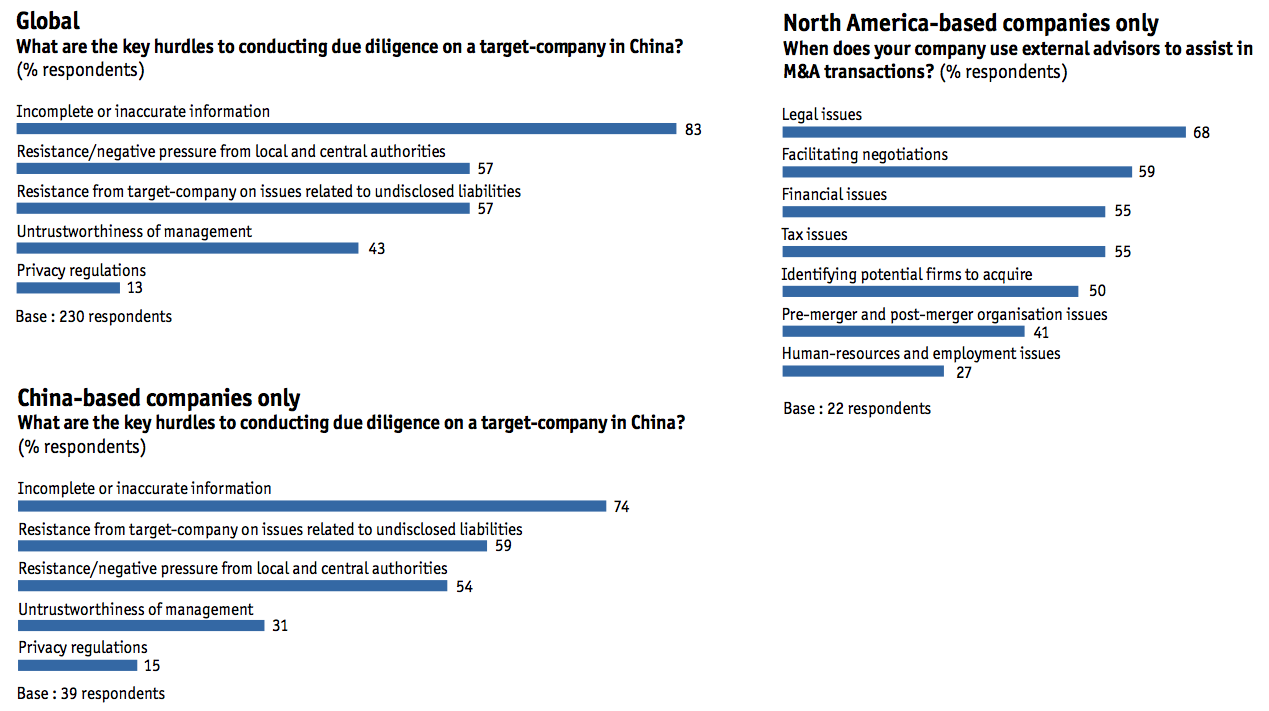

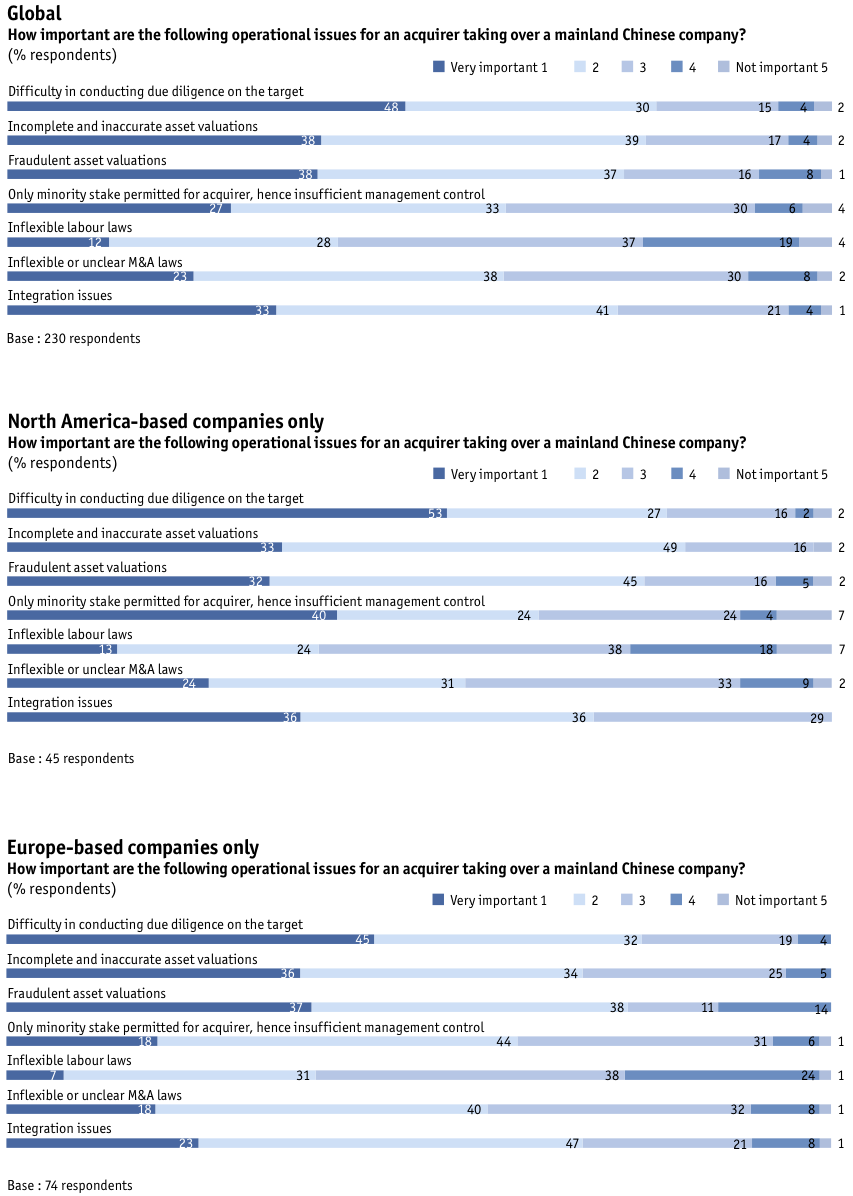

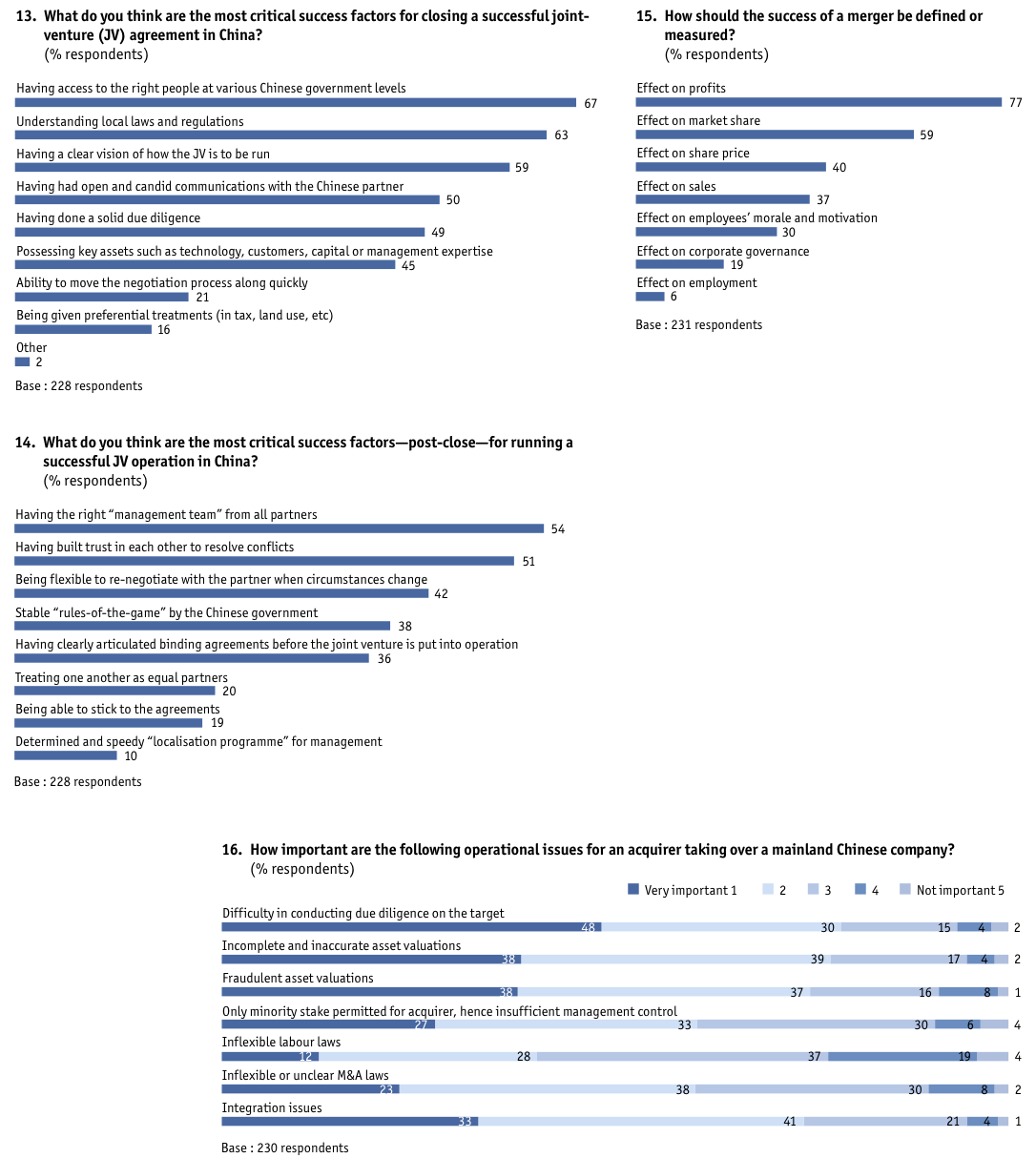

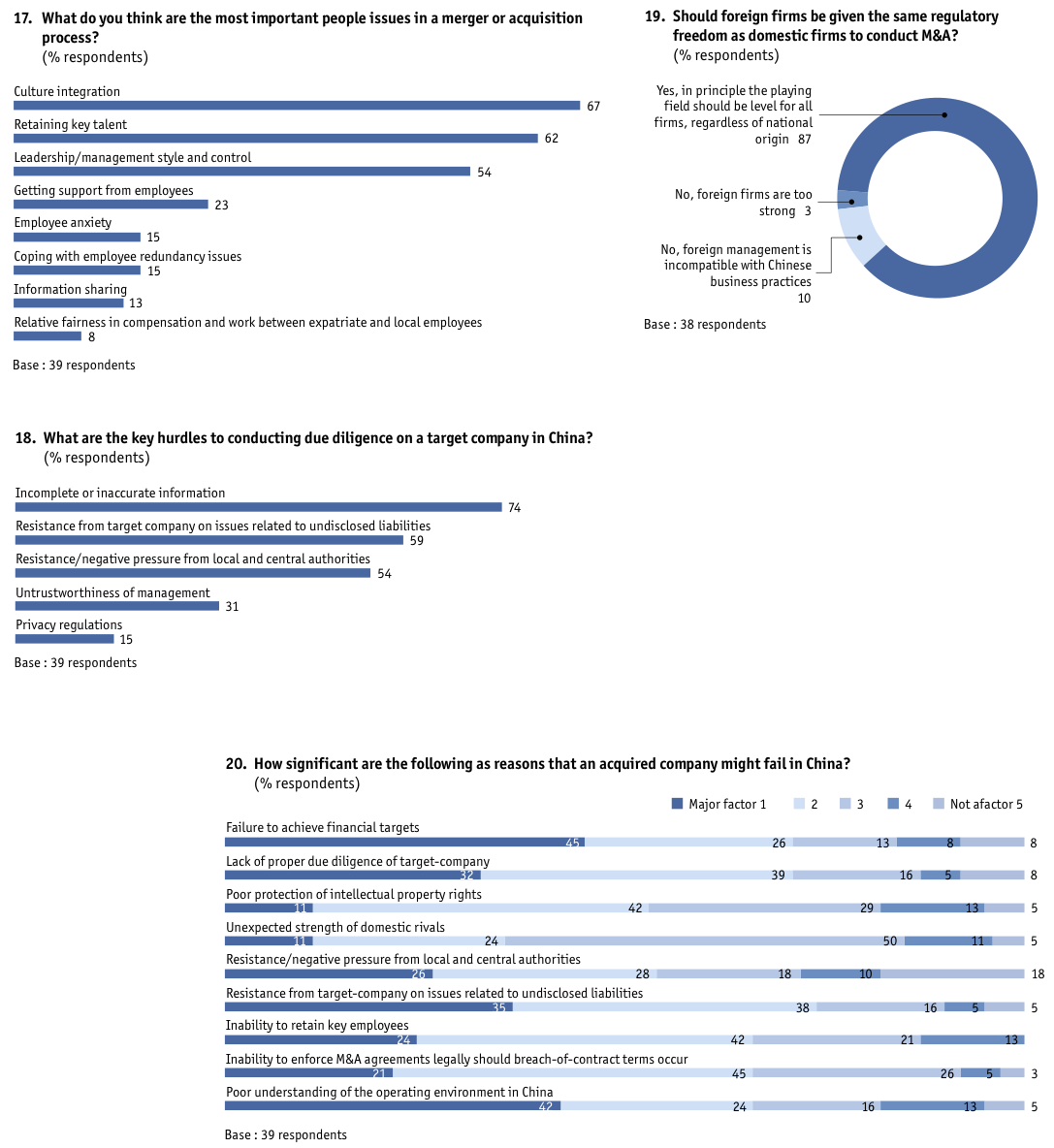

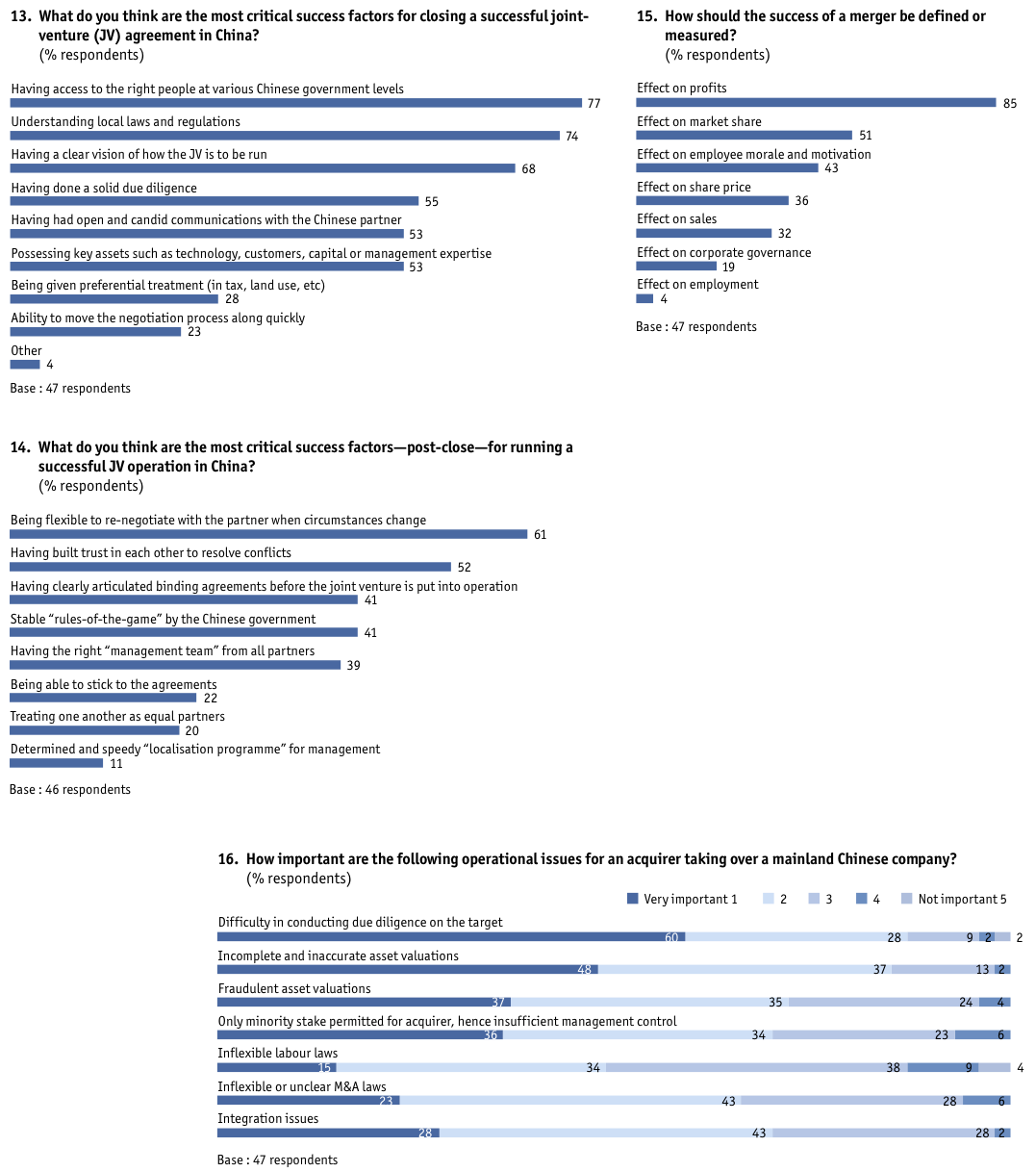

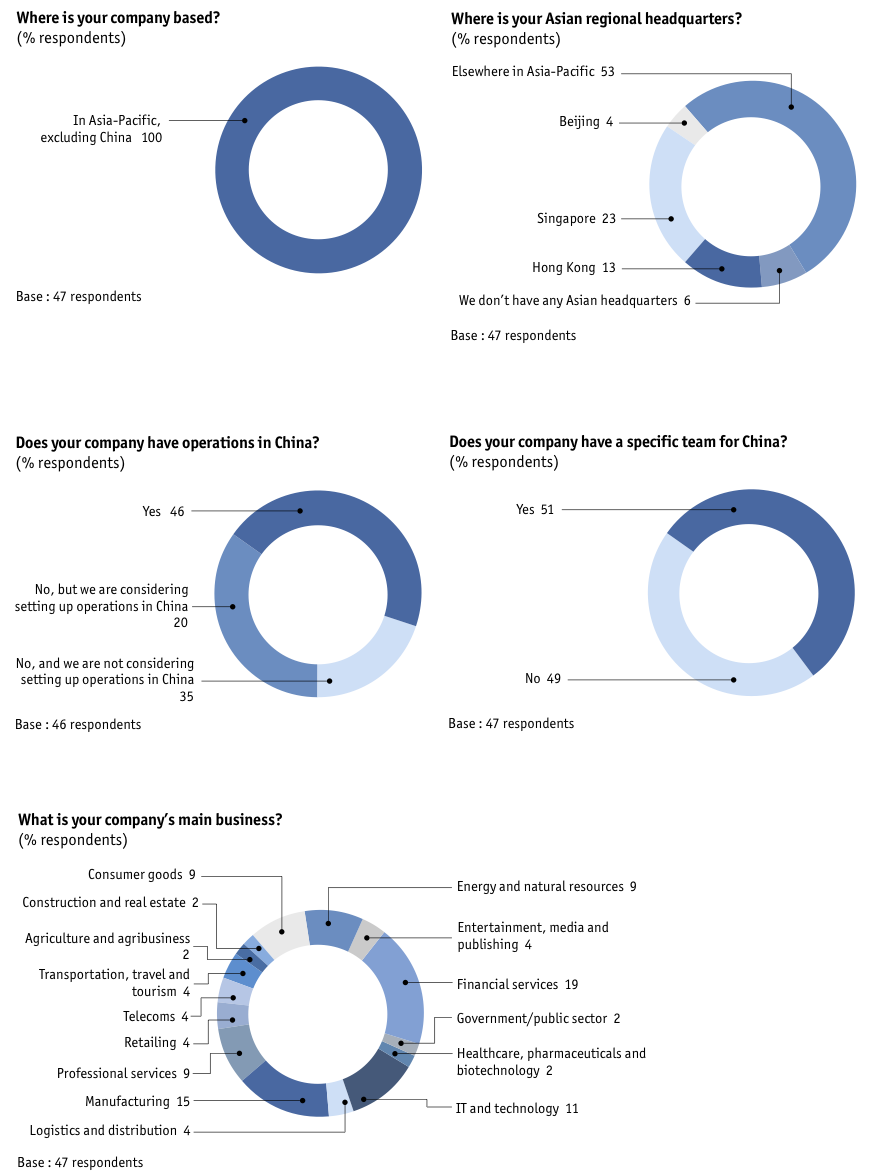

• Lack of transparency at a target-company is a major hurdle facing M&A transactions in China. So say 58% of survey respondents; 46% cite lack of information about a target. These opinions make it particularly imperative for an acquirer to conduct due diligence on a target. This is not easy, however, because of incomplete or inaccurate information on a target.

• Maintaining relationships post-deal is a major concern. Fully 43% of respondents to the global survey are worried about keeping their relationships with customers, suppliers and government authorities after an M&A transaction. Not surprisingly, foreign companies are more worried about this aspect than are domestic firms, which operate in their own territory.

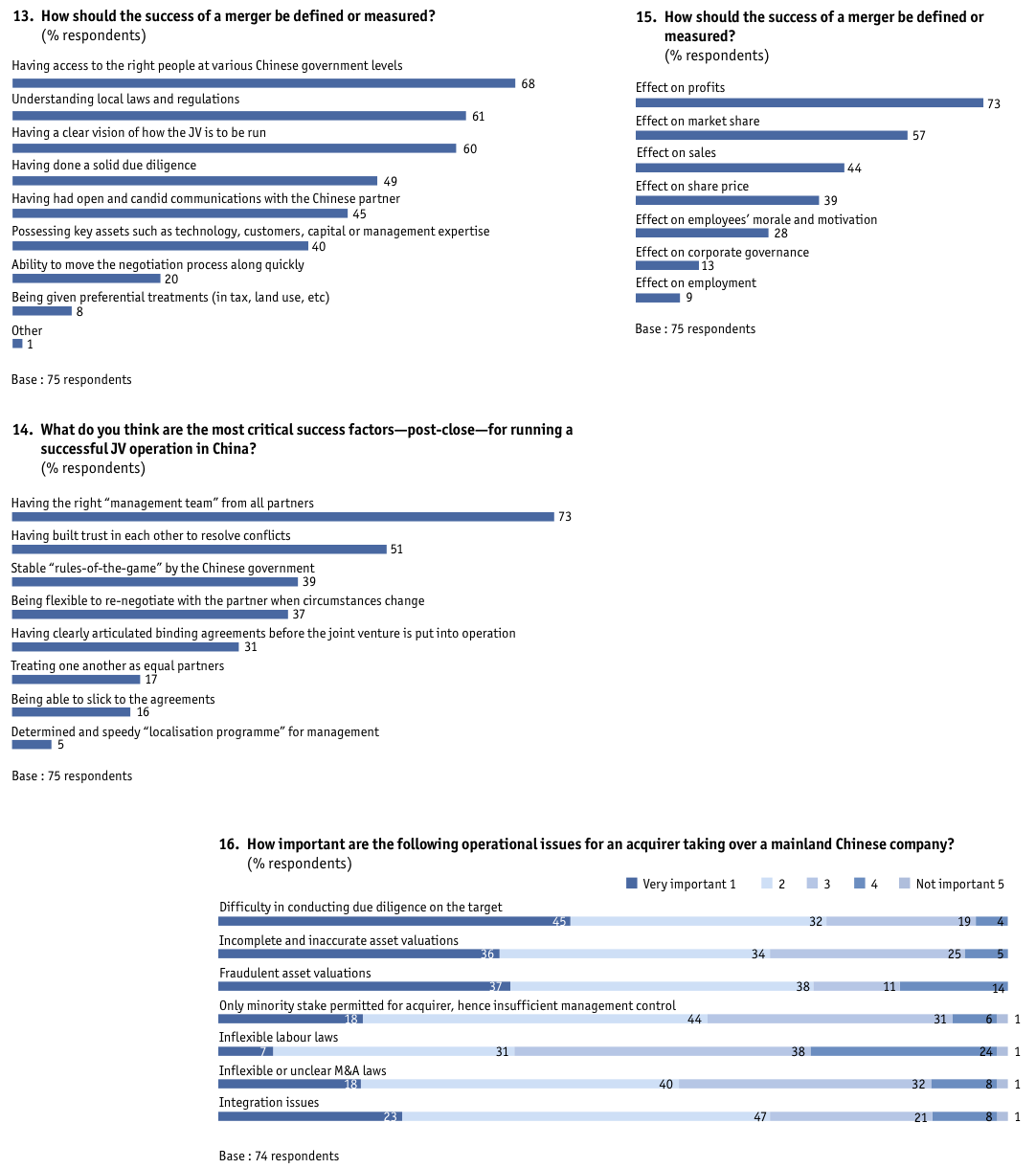

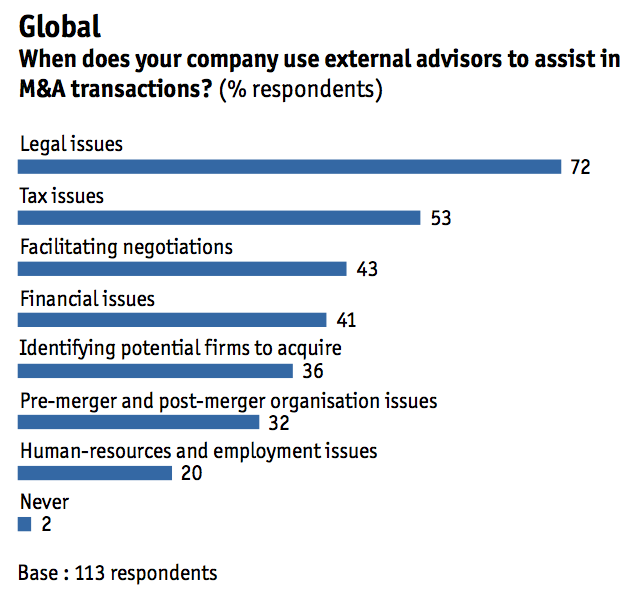

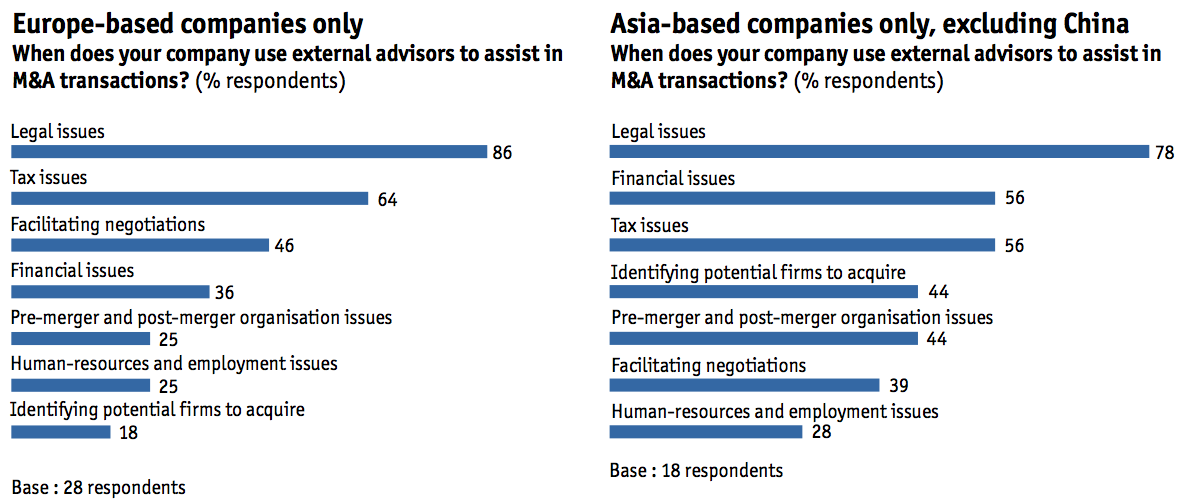

• External advisors are considered valuable to the M&A process. The majority of respondents say they will call on outside specialists for help on legal issues (72%) and tax matters (53%). Some welcome assistance with facilitating negotiations (44%), analysing financial issues (41%), and identifying potential targets (36%). Few see the need, however, for outside help in tackling organisational and human-resources issues.

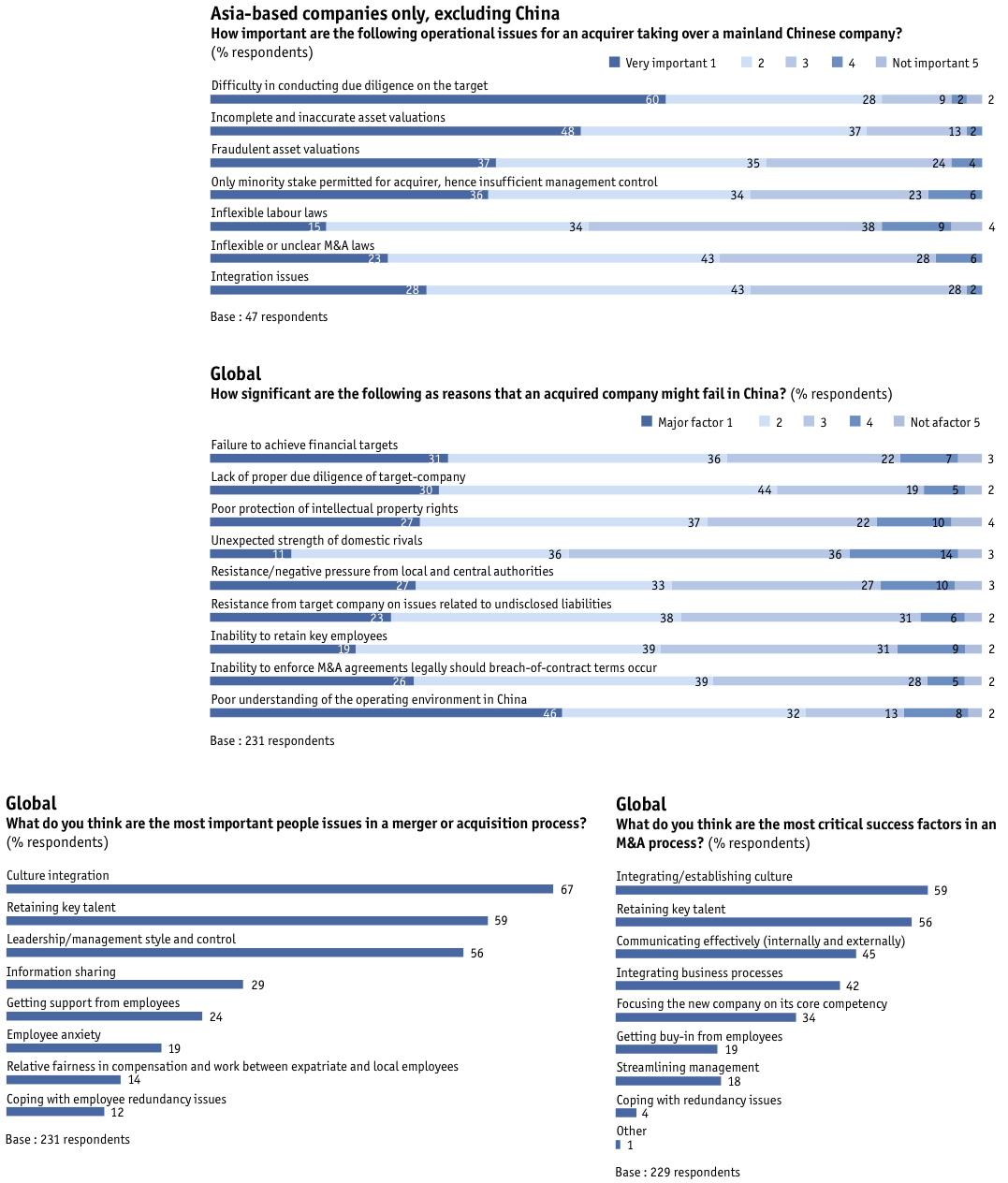

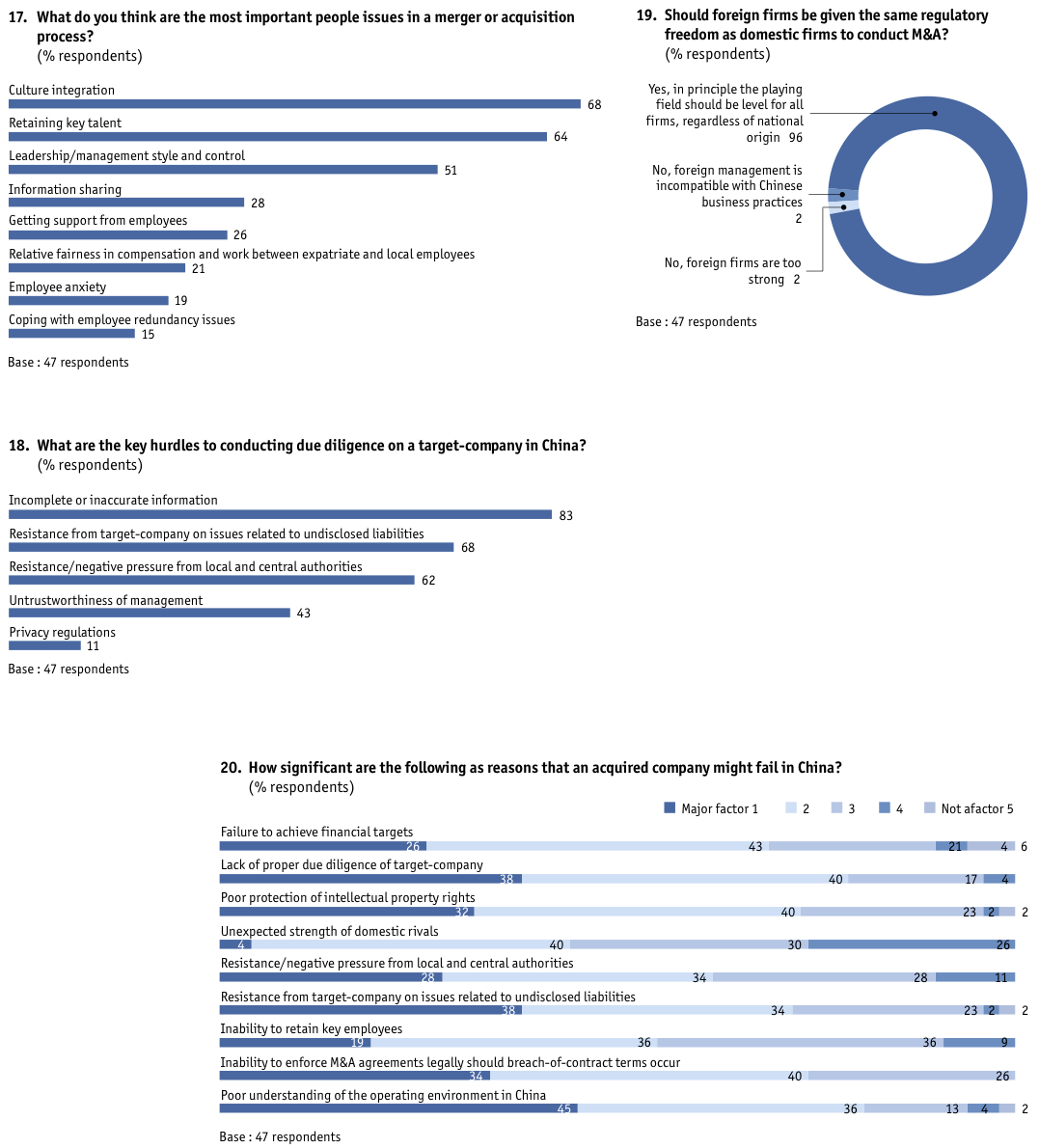

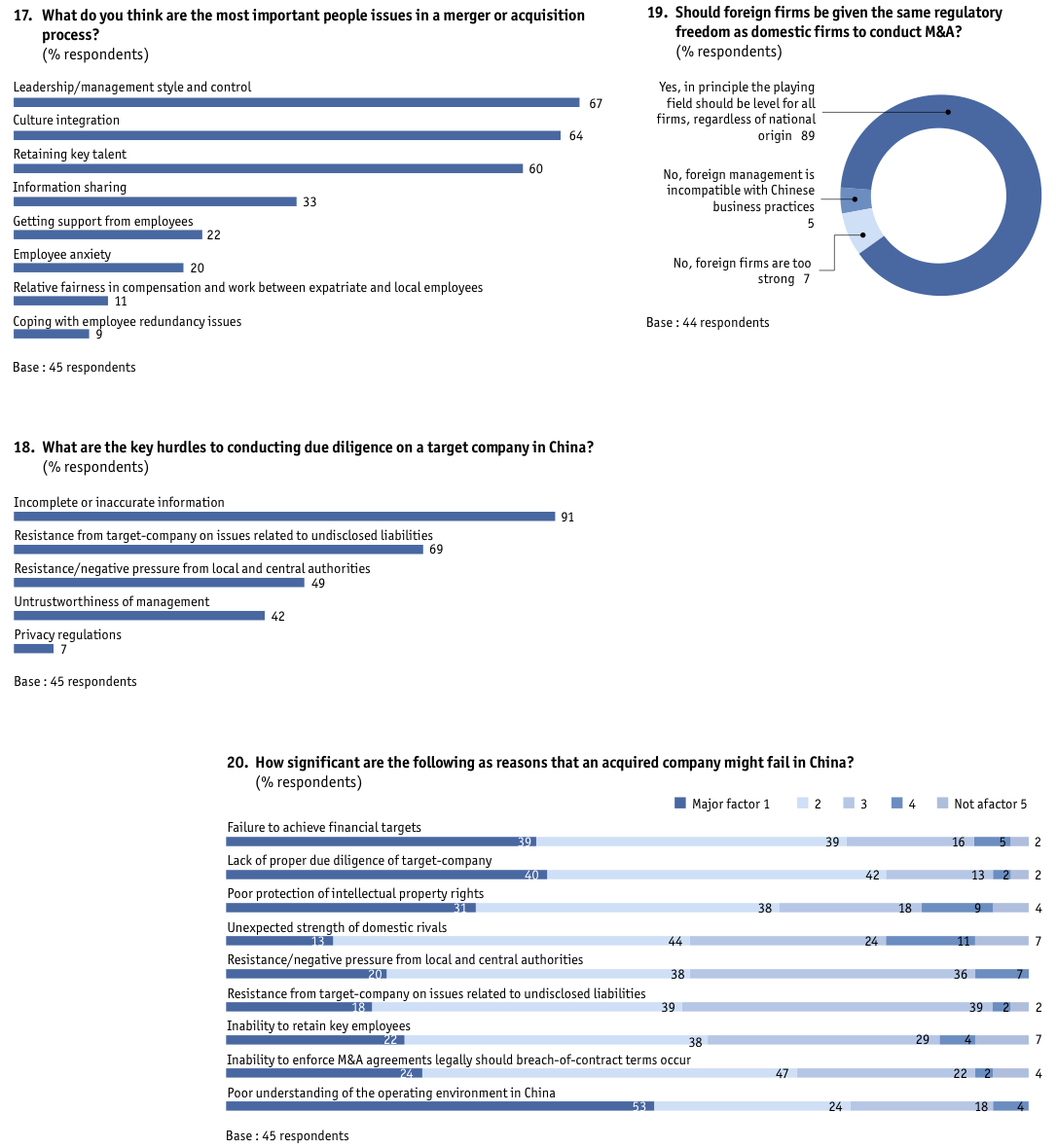

• Cultural integration is a critical people issue in the M&A process. In the global survey, 67% respondents say this is so. Of the China-based respondents, too, 62% are leery of the risk of culture clashes in merged organisations. (Nine out of the of the China-only respondents have conducted or are considering an M&A deal.) Differences in culture between firms are generally acknowledged as a major source of attrition after a merger, and yet these differences are rarely investigated closely as a deal nears closure. One common mistake is for managers in foreign companies to view Chinese companies as a bloc, and vice versa. In reality, corporate culture is much more complex, involving both national cultural mores, the culture promoted by the senior management and often a melding of both.

• Retention of key talent is a challenge in an M&A deal. The larger people issue is keeping key talent (59% of respondents mention it). Leadership or management style and control are seen as important by 56% of global respondents. There are no marked differences on these issues among China-only respondents. While an acquirer will want to have as strong a role as possible in running the target-company, it also knows that the original management team has the vital experience and contacts important in doing business in China. Companies interviewed for this study are split between using soft options like training programmes and benefits, and hard options like higher pay scales or post-acquisition contract agreements of up to three years. Companies seem to be still considering different approaches and have not settled on one method of retention.

• Redundancy is not a major people problem in China M&A deals. Only 12% of the total respondents consider redundancy to be a people issue in a merger and acquisition. One reason is that many M&A agreements require a target-company to clean up the rolls before a handover, and the cost of redundancies is often included in the selling price. Moreover, contrary to popular perception, letting workers go is much easier in China than it is in Western countries, and the costs and timeframe for doing this are relatively smaller and shorter. However, while it might be easy to let workers go, this can be time-consuming for human- resources managers who have to deal with the possible fall-out. This includes handling complaints made to local bureaux by workers made redundant.

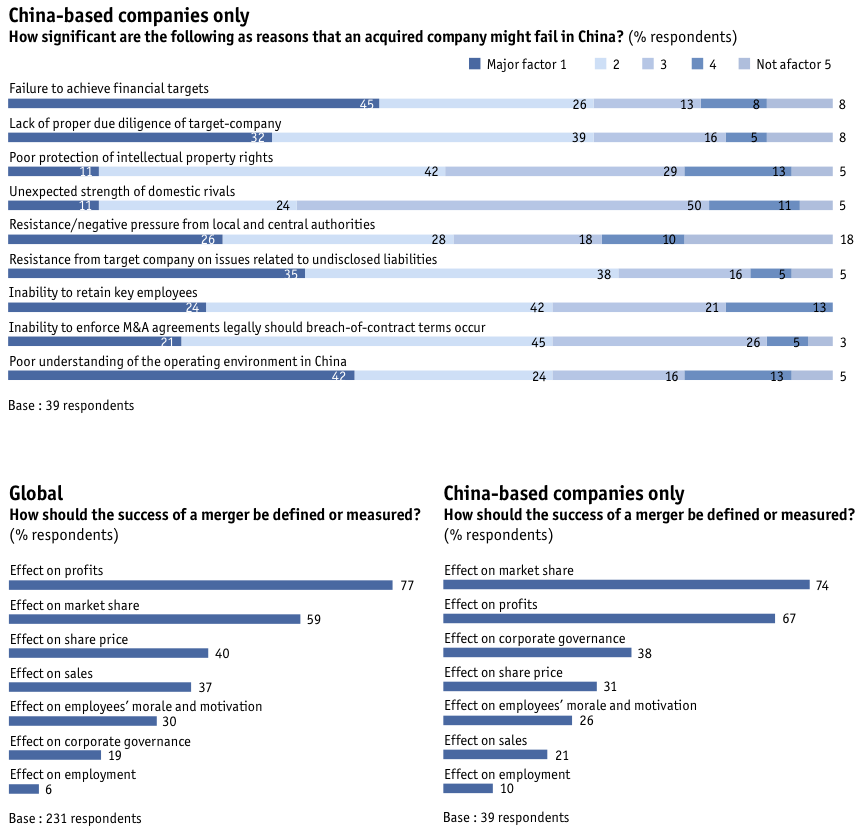

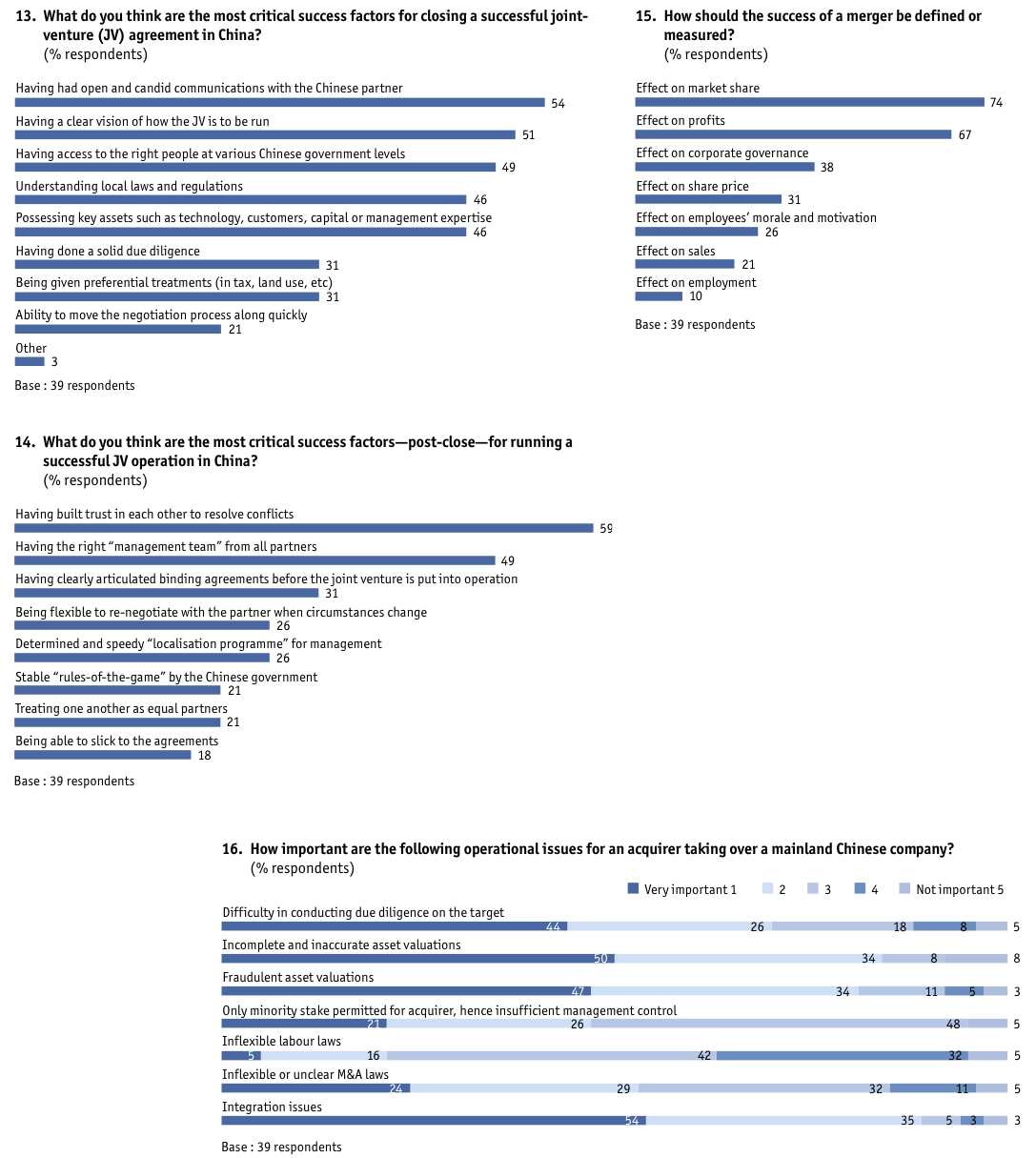

• A poor understanding of the operating environment in China is the main reason for a merged or acquired company to fail. Almost half of the respondents to the global survey say this is so. Three out of ten respondents also point to the failure to achieve financial targets, lack of proper due diligence of the target-company, poor protection of intellectual property rights, and resistance and negative pressure from local and central authorities. Surveyed executives in the China-only segment, however, put a higher emphasis on failure to achieve financial targets (45% say so), and then a poor understanding of the operating environment (42%). However, the majority of surveyed executives define the success of a merger in terms of its effect on profits (77%), followed by its effect on market share (59%), and effect on share price (37%).

Who took the survey?

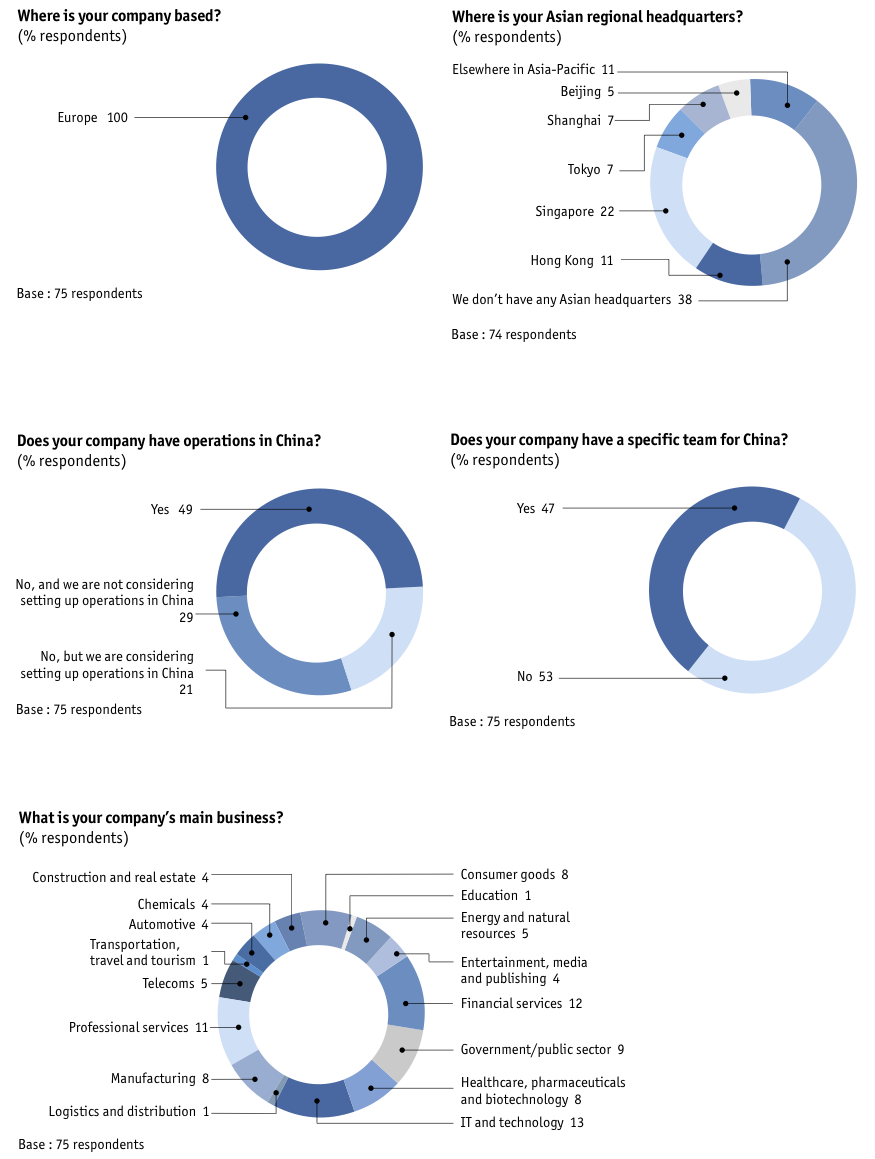

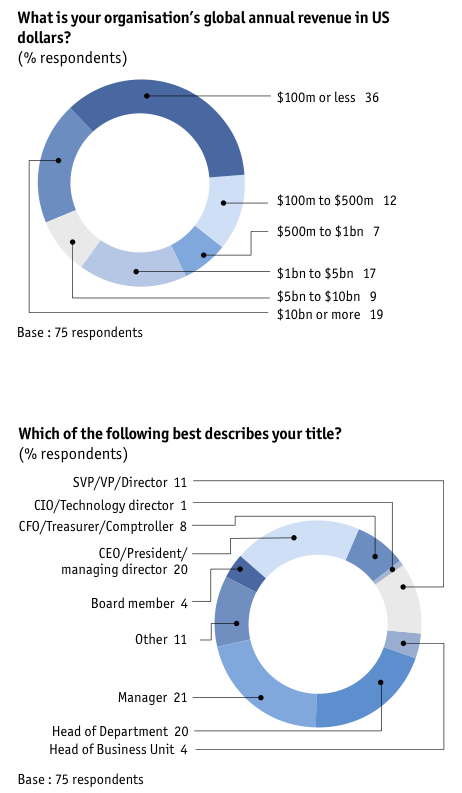

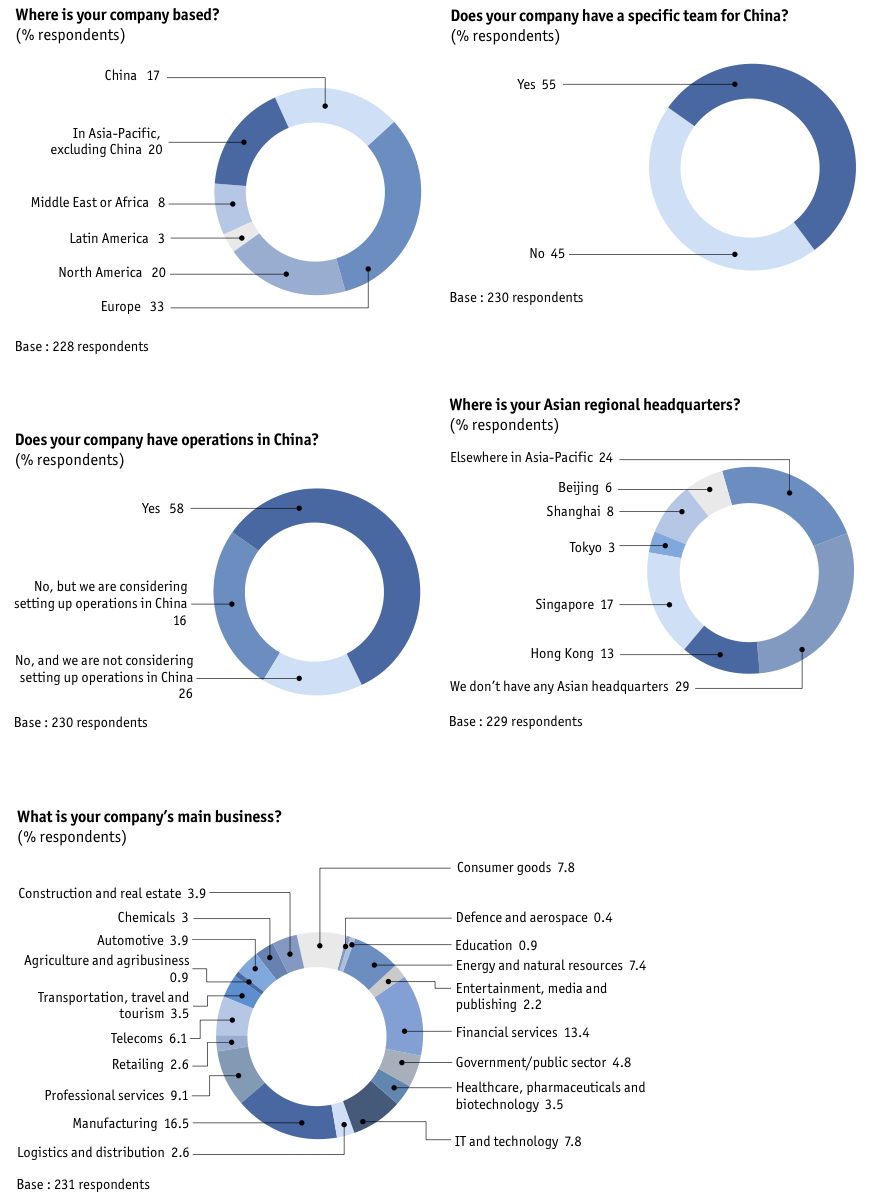

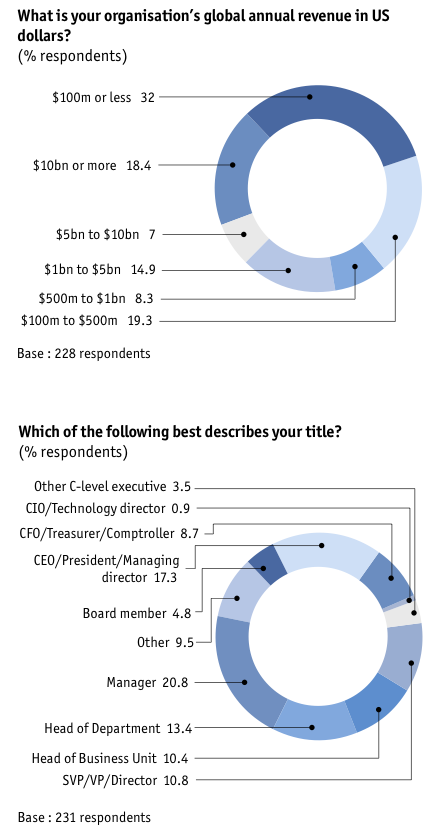

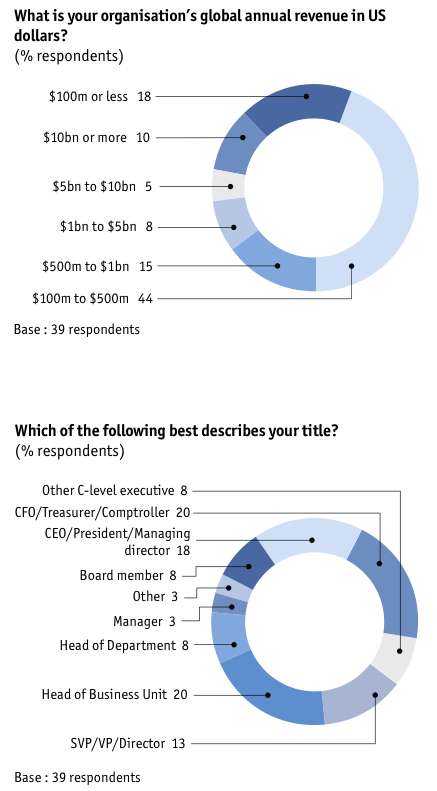

A total of 231 senior executives from companies worldwide participated in the study, with a little over half of respondents based in North America (20%) and Europe (33%). Fully 17% of respondents were based in China and another 20% elsewhere in Asia-Pacific. The remainder were from Latin America, Middle East or Africa.

The respondents were chief executives/ presidents/managing directors (17%), heads of department (13%), senior vice-presidents/vice-presidents/directors (11%), heads of business units (10%), chief financial officers/treasurers/ comptrollers (9%) and board members (5%). The rest included other C-level executives and managers.

Manufacturers accounted for 17% of respondents, followed by financial services (13%), professional services (9%), information technology and technology, and consumer goods (8% each). Other industries include energy and natural resources, telecommunications, automotive, and construction and real estate.

In terms of global annual revenue, 32% of respondents were from companies with US$100m or less, 19% were from firms with US$100m to US$500m, 8% from firms with US$500m to US$1bn, 15% from firms with US$1bn to US$5bn, 7% from firms with US$5bn to US$10bn, and 18% from firms with US$10bn or more.

Chapter 1

The playing field

Amerger-and-acquisition (M&A) spree in China is almost inevitable. The GDP has been expanding at an annual average of 9.5% since 1981, propelling the country to the ranks of the world’s largest economies. Moreover, the Chinese government is actively encouraging consolidation in such industries as banking, steel, aviation and automobiles, and is seeking foreign money and expertise for hundreds of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). It also seems serious about its commitment to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) to liberalise key industries, and to level the playing field for Chinese and non-Chinese companies alike in many (though not all) business sectors.

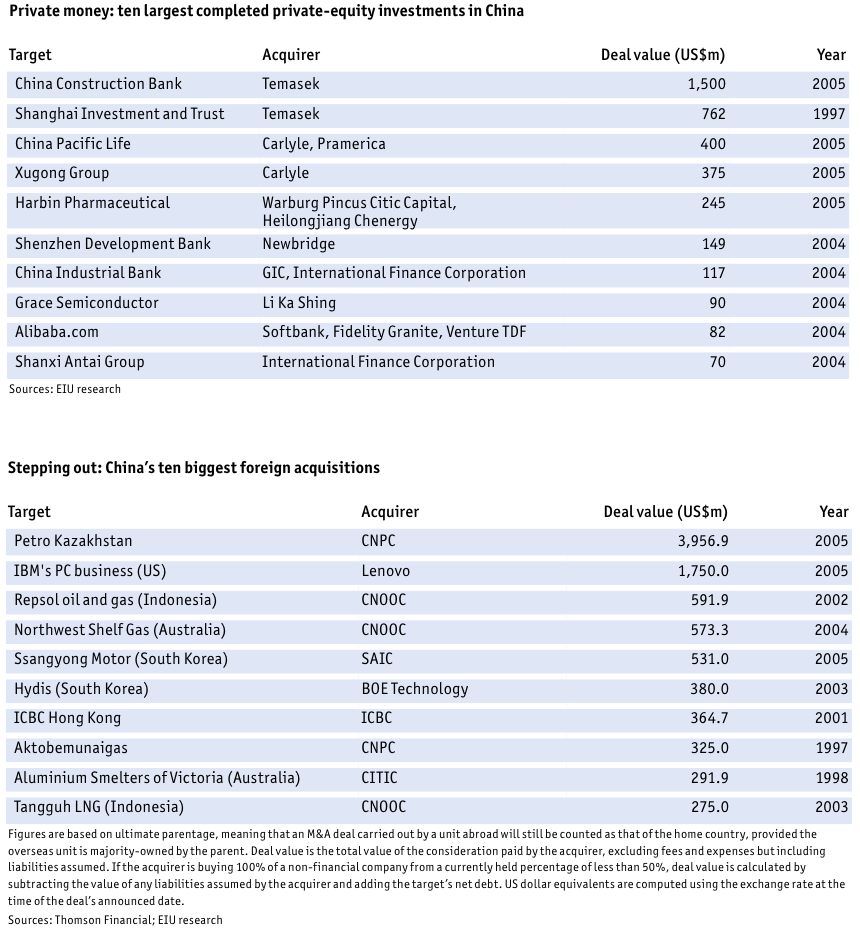

The early results are already showing up in league tables compiled by Thomson Financial, a data provider. Completed M&A transactions involving China clocked in at a paltry US$124.4m in 1985 (see table, Great leap forward). The volume had grown to US$1.9bn ten years later. In 2005 M&A activity involving China, as target and acquirer, topped US$28.5bn, 14 times the deal volume ten years ago. The headline transactions included the US$3.9bn purchase of minority stakes in China Construction Bank by Bank of America of the US and Temasek Holdings of Singapore, as well as the nearly US$4bn takeover of PetroKazakhstan by China National Petroleum.

Room to grow

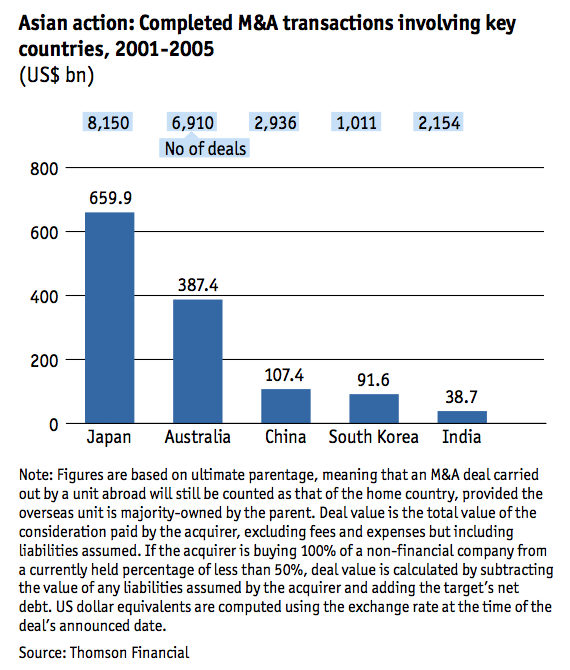

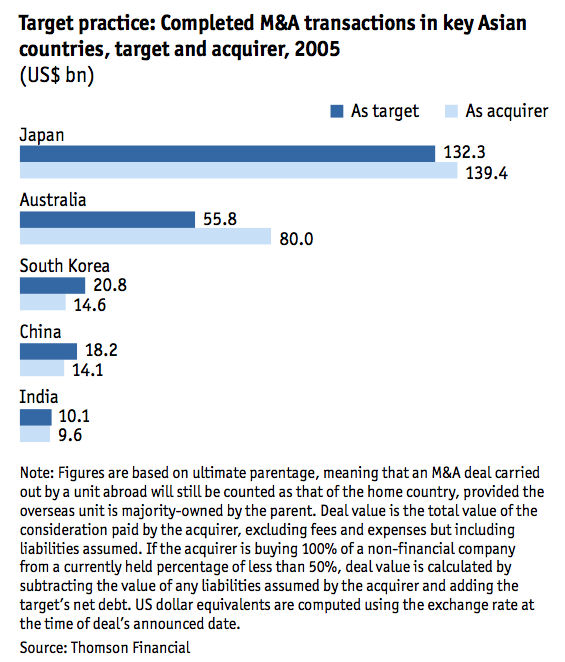

Over the past five years, China-related M&A has totalled US$107.4bn, the value of 2,936 transactions (see table, Asian action). This is 17% larger than the value reported for South Korea, which until 2002 was ahead of China in M&A league tables. Compared with Australia and Japan, however, China’s M&A deals are still up to three and six times smaller, respectively.

What this tells us is that the M&A market in China still has a lot of room to grow, especially since the country’s GDP and its private consumption have been robust.

Another relevant trend here is the rising proportion of inward M&A investment in China to total foreign direct investment (FDI). The United Nations agency for trade and development, UNCTAD, estimates that cross-border M&A sales as a percentage of FDI into China reached 5% in 2001, decelerated to 3.9% in 2002 and then jumped to 7.1% in 2003.

Last year, according to Thomson Financial’s tracking, inward M&A deals in China topped US$13bn. Total China FDI in 2005 was US$60.3bn, suggesting that the proportion of M&A transactions to FDI last year had surged to 21.5%. That’s an impressive increase, but still far behind the global average of 53.1% in 2003—again implying more room for growth for M&A activity in China.

Last year, however, China was slightly behind South Korea in completed M&A transactions, whether foreign-domestic, domestic-domestic, or domestic-foreign (see table, Target practice).

But like South Korea and India, China remained more of a target for mergers and acquisitions than a net acquirer of assets, as Japan and Australia were in 2005. China, of course, is still a less developed economy than either Japan or Australia, despite its world-beating GDP growth rates in the past two decades.

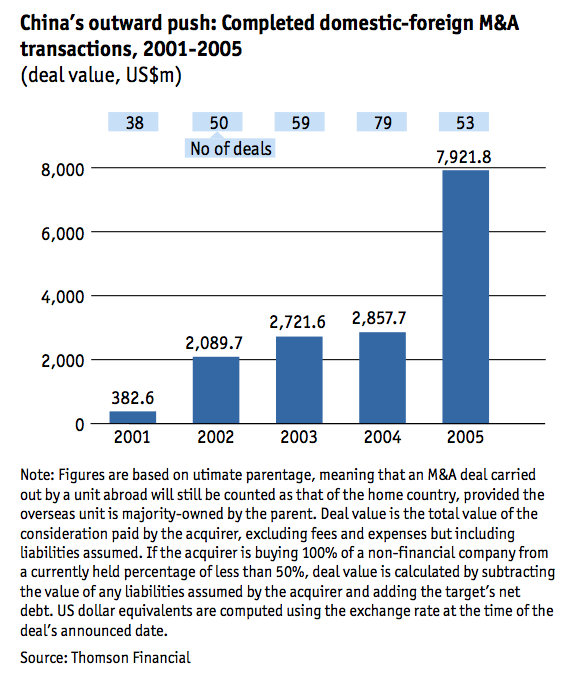

At US$7.9bn, China’s outward M&A set a record last year (see table, China’s outward push), but it is doubtful whether that fast a pace can be sustained. Oil companies under state orders to secure national energy accounted for nearly half of that amount.

Other Chinese companies remain hobbled by restrictions on the outward movement of capital and, in any case, many still lack the “management bandwidth”, as an M&A professional puts it, to successfully run global entities. The overwhelming majority, in fact, are focused inward. In an Economist Intelligence Unit study in 2005 entitled Domestic companies in China: Taking on the competition, nine out of ten respondents to a survey said their company’s main target would be the home market in the next three years.

Politics can also be an impediment. Last year, Chinese oil company CNOOC alarmed the political establishment in the US when it unveiled a US$18.5bn bid for a mid-sized US firm, Unocal (see CNOOC: a Chinese oil company steps out). CNOOC dropped the proposed purchase when it became clear that the US Congress would oppose the deal in the belief that it would harm US interests.

Another announced bid, by Chinese appliance-maker Haier for US washing machine brand Maytag, also failed in 2005 when its US$1.28bn offer was topped by Whirlpool’s US$1.37bn tender.

Drivers of M&A

Not that Chinese outward M&A would dry up completely. There are oil and other resources in countries where the US and other developed countries fear (or are unwilling) to tread, among them Sudan and Myanmar. Even so, the expectation is that the bulk of M&A volume going forward will be accounted for by foreigners investing in, or acquiring, domestic companies, and by domestic companies merging with and acquiring each other. The key drivers here include rising purchasing power and private consumption, the government’s desire for foreign funds and expertise for SOEs as it fully opens sectors of the economy to foreign competition, and a more relaxed regulatory regime that, for example, has expanded the scope and geographical reach of wholly owned foreign enterprises (WOFEs).

As tracked by the Economist Intelligence Unit, private consumption in China has been growing by better than 6% annually (and more than 10% in some years) since 1991, and is forecast to continue expanding by 7%-9% a year from 2006 to 2012. Personal disposable income has been keeping pace at more or less the same rate, growing 9.4% and 8.9% in 2004 and 2005, respectively, and is forecast to expand by 7% this year and next. The country is rapidly emerging as a domestic market in its own right, particularly in the coastal provinces, where GDP per-capita now tops US$2,100. That rich crescent spanning Liaoning province in the north to Guangdong down south is home to 482m Chinese, larger than the entire US population of 298m.

Demand begets supply, and so hundreds of thousands of local private-sector firms have sprung up to compete with state-owned companies. Sino-foreign joint ventures, which in the early years focused on China as a cheap source of labour to make goods for export, are now targeting Chinese consumers themselves. Some industries have already become very crowded, including those for automobiles, home appliances, mobile phones and consumer electronics—and therefore ripe for consolidation. Cherry-picking is well under way in beverages, with the US’s Anheuser-Busch, Europe’s InBev (formerly known as Interbrew), South Africa’s SABMiller and Japan’s Kirin merrily snapping up Chinese breweries, brands and sales networks.

The central government is giving M&A a big push. It has mandated consolidation in such fragmented sectors as steel and aviation, although the companies themselves, many of them state-owned, have been dragging their feet. After approving the purchase by foreign giants such as HSBC, Bank of America and Temasek Holdings of small stakeholdings in state-owned mega-banks, regulators in Beijing are considering a proposal by a consortium led by Citigroup of the US to buy 80% of bankrupt Guangdong Development Bank, China’s 11th largest financial institution. Current rules limit foreign participation in banks at 25% in aggregate, so an exception made here would signal a significant change in thinking.

China’s efforts to streamline regulatory hurdles are also driving M&A activity. The central government issued the Provisional Rules on the Merger and Acquisition of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors in 2003, which considerably clarified the M&A process in China. The next year, the Ministry of Commerce promulgated the Administrative Measures Governing Foreign Investment in Commercial Sectors. These rules allowed WOFEs to engage in commission agency, wholesaling and retailing (from just manufacturing for export previously) and abolished geographical restrictions on foreign- invested wholesaling and retailing operations.

Some joint ventures have been dissolved as foreign companies opted to acquire the assets of the partnership and inject them into a WOFE. One high-profile example is global logistics company UPS, which in 2005 took direct control of international express operations in 23 cities it previously co-owned with Sinotrans, a Chinese SOE. UPS paid Sinotrans US$100m, a windfall that the Chinese company will use to enhance its own operations — and perhaps to fuel its own M&A plans.

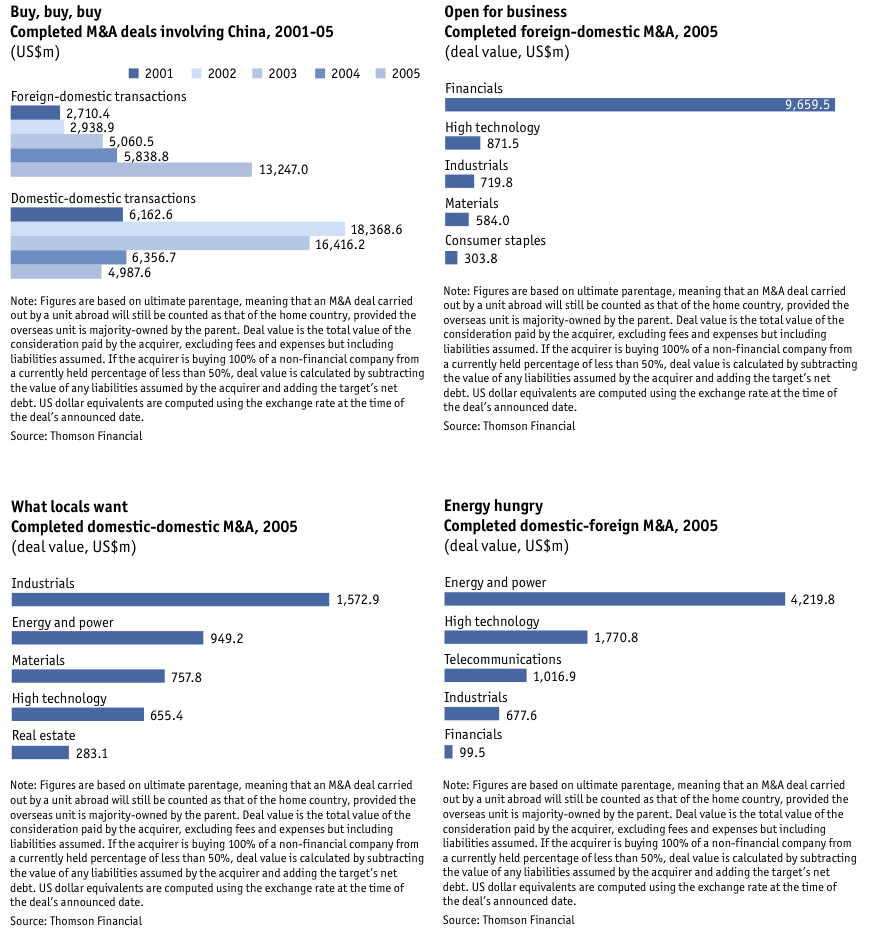

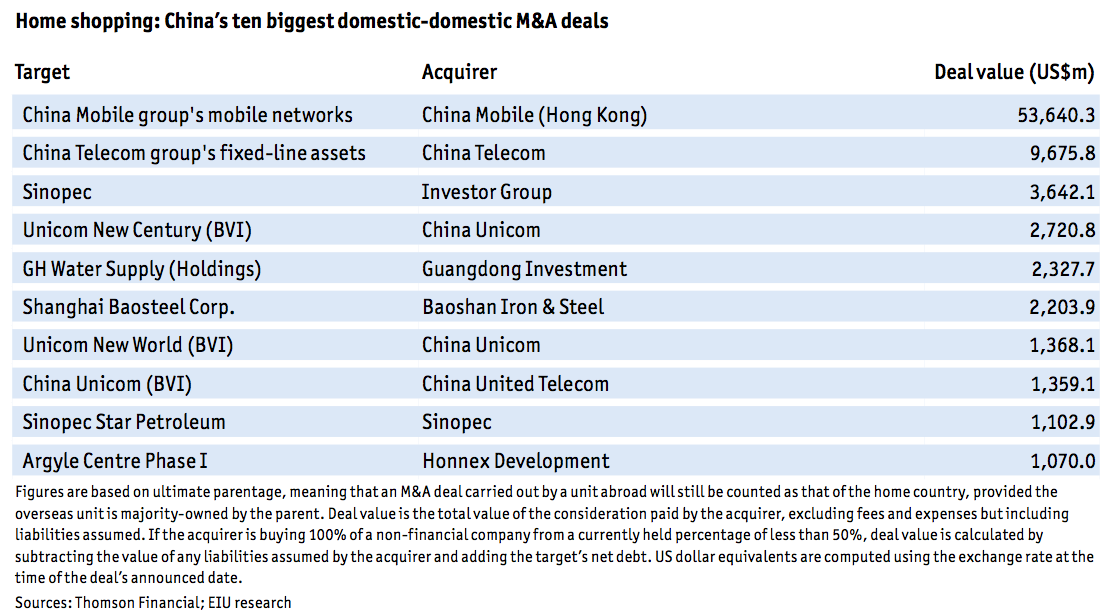

Domestic-domestic transactions are also on the rise (see table, Buy, buy, buy), peaking in 2002 and 2003 when state-owned companies like China Mobile and China Unicom hived off units for listing in Hong Kong and the US, and then injected their assets into the new public entities. The government is continuing its campaign to force state-owned enterprises to consolidate, which has resulted in such deals as Baoshan Iron and Steel’s acquisition for US$2.2bn of Shanghai Baosteel in 2001. But domestic private-sector consolidation is also taking place, exemplified by the merger this year of two Shanghai advertising companies, Focus Media and Target Media.

In a sense, what is behind many of these drivers is the WTO, or to be precise, China’s promises to open certain sectors of its economy to foreign players when it was accepted into the WTO in 2001. The country has delivered on a number of those pledges, such as raising the cap on foreign ownership in basic telecommunications services to 49% and abolishing requirements that had forced foreign car makers to enter into joint ventures with local companies. It has also promised to lift geographical restrictions on foreign operations in the banking and insurance sectors by late 2006.

The WTO commitments explain in part the Chinese government’s consolidation drive, which rests on the assumption that large entities will have a greater chance of competing against the anticipated entry of global giants. For their part, foreign companies are getting their feet wet with limited M&A initiatives to get a feel of the process and learn the ways of the local competition in anticipation of a full-scale assault when (or if) the gates are finally thrown open. This is the same imperative that is beginning to dictate the tempo of M&A activities among domestic private-sector companies. Often upon the prodding of private- equity investors, they are beginning to regard inorganic growth as a rapid way of achieving scale.

Private-equity investors can potentially play a key role in M&A transactions in China going forward. With seats on the board and their status as trusted advisers of the founding entrepreneur, they can make the case for a merger or acquisition that would maximise the company’s value, along with their minority stakes. It will take patience, given entrepreneurs’ understandable attachment to their enterprises, but there could be a snowball effect if a significant number of firms jump on board—particularly if bottom lines at some of the weaker players deteriorate in an economic slowdown. In turn, consolidation in China’s highly fragmented industries can stimulate M&A interest among foreign companies, since there would then be sizeable targets to pursue.

Sectors of choice

In foreign-domestic M&A, the overwhelmingly favoured sector last year was finance, particularly the banks, which attracted US$9.7bn in completed acquisitions (see Open for business). This is not surprising given the government’s focus on strengthening the fragile financial system and the scheduled full opening of the banking industry. Far behind in second place was high technology, including computers, followed by industrials, especially cars and ports, materials (aluminium, cement and paper) and consumer staples.

In domestic-domestic M&A, the hottest sectors last year were industrials, energy and power, materials, high technology and real estate. The deals tended to cluster around state-owned companies purchasing their own subsidiaries (for example, Huadian Power International’s acquisition of Huadian Xinxiang Power) or each other (e.g., PetroChina buying Liaohe Jinma Oilfield and Jinzhou Petrochemical).

In domestic-foreign M&A, energy and power accounted for 46% of all outward investments in 2005, with high technology (including Lenovo’s purchase of IBM’s personal-computer division) coming second at 33%. Telecommunications had an 11% share, industrials 7%, and financials a tiny 1%.

A glimpse of the future

While most completed transactions in 2005 were in financials, industrials, high technology, energy and power, anecdotal evidence suggests foreign interest spans the whole spectrum in China. Indeed, in this white paper’s survey results, discussed more fully in Chapter 3, at least three out of ten respondents from North America, Europe and Asia say their company has conducted or is considering an M&A transaction in China. North American firms are the most gung-ho, with 42% saying they are pursuing M&A in China. One reason for foreigners not moving as fast as they want is China’s restrictive regulations, cited as an impediment to M&A by 51% of respondents. Foreign participation in basic telecoms services is capped at 49% and 25% in banking, for example. Government approval is required for large and fixed-asset projects in infrastructure, agriculture and nine other industries, and for projects involving rare or precious mineral resources and in industries requiring central planning by the state, a catch-all requirement that can apply to any sector.

The paperwork becomes more stringent and time-consuming in an M&A, requiring scrutiny from regulators to ascertain, among many other things, that the amount to be paid does not exceed the allowed multiple of the acquirer’s registered capital. For example, firms with registered capital of less than US$1.2m can invest up to 1.43 times that amount, while those with more than US$12m can pay only three times that amount.

That said, M&A regulations have been revised a number of times over the past five years and a majority of multinational companies still view China as an opportunity not to be missed. “They have to come here,” says Brinton Scott, a lawyer in Shanghai with international law firm Herbert Smith. “It’s either die now or die later.”

These restrictions do not apply to domestic companies, although they have to comply with capital and other requirements. Fully 90% of mainland enterprises in our survey say they have conducted or are considering launching an M&A transaction in the domestic market. They are motivated by business reasons, mainly corporate restructuring and consolidation in their industry (51%), rather than by pressure from the government (5%). It seems that China’s companies, and the foreign firms that are courting and competing with them, are in for some very interesting times.

CNOOC: a Chinese oil company steps out

When CNOOC, China’s third-largest oil company, bought the Indonesian oil-and-gas reserves of Spain’s Repsol in 2003, the outward investment went off without a hitch. CNOOC paid US$585m, equal to US$1.64 per barrel of oil equivalent of proved reserves, a bargain then and even more so today, when oil is selling at US$60 or more per barrel. So when CNOOC made a bid in 2005 for Unocal, a mid-sized US oil firm, it was fairly confident it knew what to do.

How wrong it was. “We were very, very surprised,” Yang Hua, CNOOC’s chief financial officer, said of the firestorm the proposed acquisition created in the US. The lead negotiator in both the Indonesian and American M&A transactions, he spoke to CFO Asia, an Economist Intelligence Unit sister publication. CNOOC withdrew its offer in the face of opposition from the US Congress, but remains open to US deals. “It’s not like we’re going to take over your jobs or take your resources back to China,” Mr Yang said. “We’re happy to just take our profits and deliver them to our shareholders.”

This is, of course, the objective of any corporation—except that CNOOC is majority controlled by the communist government in China. It is listed in Hong Kong and New York, and Beijing has not been known to interfere in any way with CNOOC’s business decisions.

But oil is a strategic resource and China is desperate to have access to a lot of it to continue fuelling its economic expansion. The news that CNOOC’s acquisition will be partly funded by concessionary loans from a Chinese government bank further stoked US paranoia.

CNOOC points to its Indonesian purchase as proof of its benign intentions. It initially assigned only two Chinese managers to oversee the unit. Currently, just 20 of 900 employees are Chinese.

No worker was fired, and the Indonesian acquisition continues to operate in much the same way as it has always done. After all, extracting stuff from a hole in the ground requires the same technology and skills wherever you are in the world. CNOOC says nothing at Unocal would have changed had it succeeded in buying it.

Looking back, Mr Yang says CNOOC has learned valuable lessons for its next foray into the US. It will make sure to effectively communicate its benign intentions at the outset, in addition to ultra-competitive pricing.

Given the hysteria in March 2006 over a bid by Dubai’s state-owned DP World to buy several US sea ports, however, the climate for foreign investment, especially from China, is not exactly ideal. CNOOC may continue to look, but it is likely that its money would go to the world’s more hospitable places.

Chapter 2

Who are the players?

It takes two, as they say, to tango, and so it is with a merger and acquisition in China—you need an acquirer and a target to dance the M&A. At this time, the majority of acquirers of Chinese assets are foreigners, primarily from the US and Europe. They fall under two broad categories. The first are strategic investors, which are operating companies buying other businesses to expand or defend market share and enhance profitability. The second are private-equity investors, which buy minority stakes in start-ups, mid-growth enterprises and mature businesses using funds pooled from individual investors, with the aim of eventually selling out at a profit through such exits as an initial public offering or a sale to strategic investors.

The targets of these foreign (and some domestic) acquirers can be grouped into four general categories. The first are state-owned enterprises (SOEs) under pressure from the central government to consolidate as China allows foreigners into their industries, which include iron and steel, automobiles and financial services. The second group are money-losing enterprises owned by the central government or provincial authorities desperate to salvage what they can by selling off non-core assets or even the whole operations. The third group comprises state enterprises set up to build and operate infrastructure facilities such as toll roads that are now selling off concessions to monetise future cash flows.

The last group is in some ways the most interesting. It is composed of private-sector companies of varying sizes in various stages of development that need capital, management expertise and technology to compete in increasingly crowded markets. Most are still too small to be of much interest to foreign strategic investors, but they are attractive to private-equity investors and to larger Chinese companies. They typically operate in the newer, less high-profile sectors of the economy, such as the Internet and e-commerce, and non-strategic industries like apparel, fast food and consumer electronics. What they lack in individual size they make up for in collective volume—the private sector is now estimated to account for about 60% of China’s economic activities.

Also closely watched is a small coterie of large Chinese enterprises that are moving the other way, using capital accumulated in China to acquire assets abroad. Currently, these globalising companies are mostly resources companies, particularly those in oil, which do not necessarily need sophisticated management expertise to integrate into their operations what are essentially holes in the ground. The process of extracting, transporting and processing minerals is basically the same everywhere. The more challenging M&A deals are those that require post-merger global branding, marketing, research and development, and other management skills. This is where aspiring Chinese multinational companies may fall short, one reason why outward M&A in China is likely to remain limited at this time.

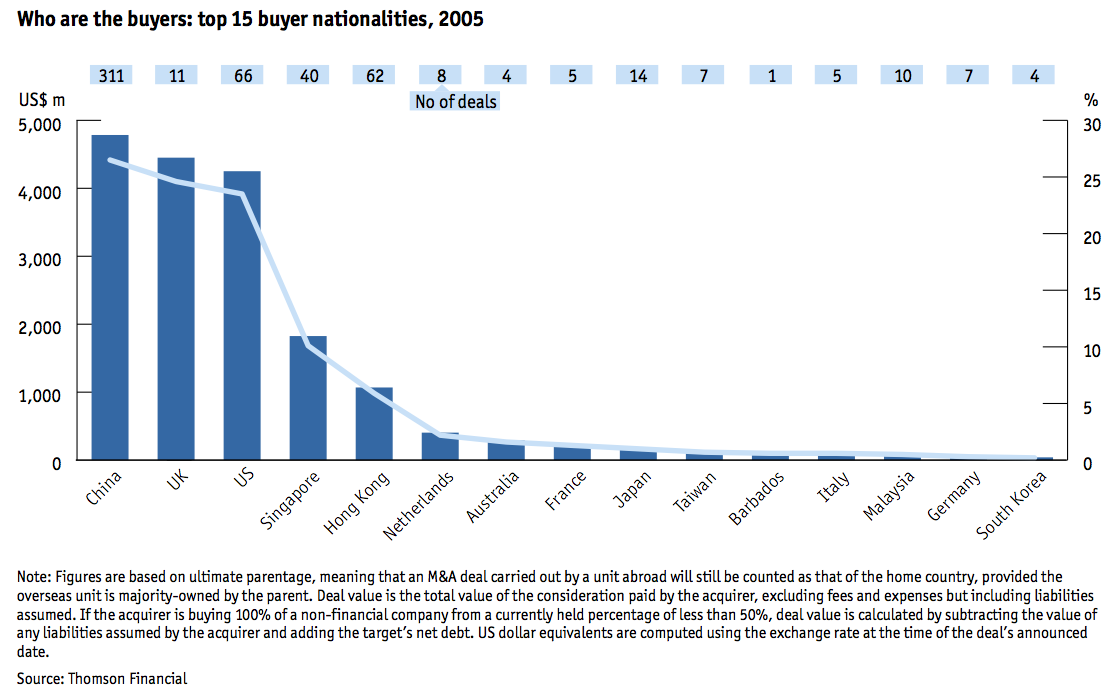

The acquirers

In 2005 mainland Chinese firms spent US$4.8bn on M&A deals with other Chinese companies as targets, according to Thomson Financial, a data provider (see Who are the buyers). The majority of the wheeling-dealing, however, was made by foreign companies, specifically those from the UK and the US, which accounted for a combined 48% of total M&A deal volume in 2005. The significant Asia-Pacific acquirers were Singapore (10%) and Hong Kong (6%), with Australia (2%), Japan (1%) and Taiwan (0.7%) far behind.

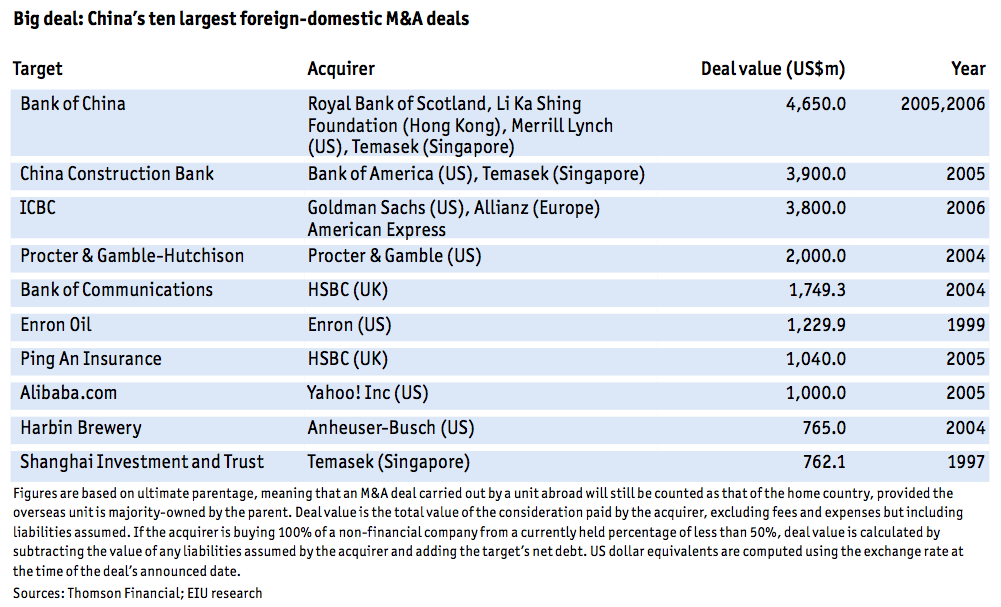

• Foreign strategic investors. The foreign companies that made the biggest M&A waves in China in 2005 and up until February 12th 2006 are the global financial giants, among them Bank of America, HSBC, Royal Bank of Scotland and Goldman Sachs (see Big deal).

Sceptics have criticised the billions of dollars that these acquirers have paid for what are, essentially, badly managed white elephants burdened by sub-standard earnings and poor assets. Balance sheets have begun to show improvements, it is true, but mainly because government bailouts allowed mega-banks like Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, Bank of China, and China Construction Bank to offload huge amounts of non-performing assets. The injections do not necessarily strengthen management and other systems, nor do they improve management quality and help ensure new loans will not turn bad.

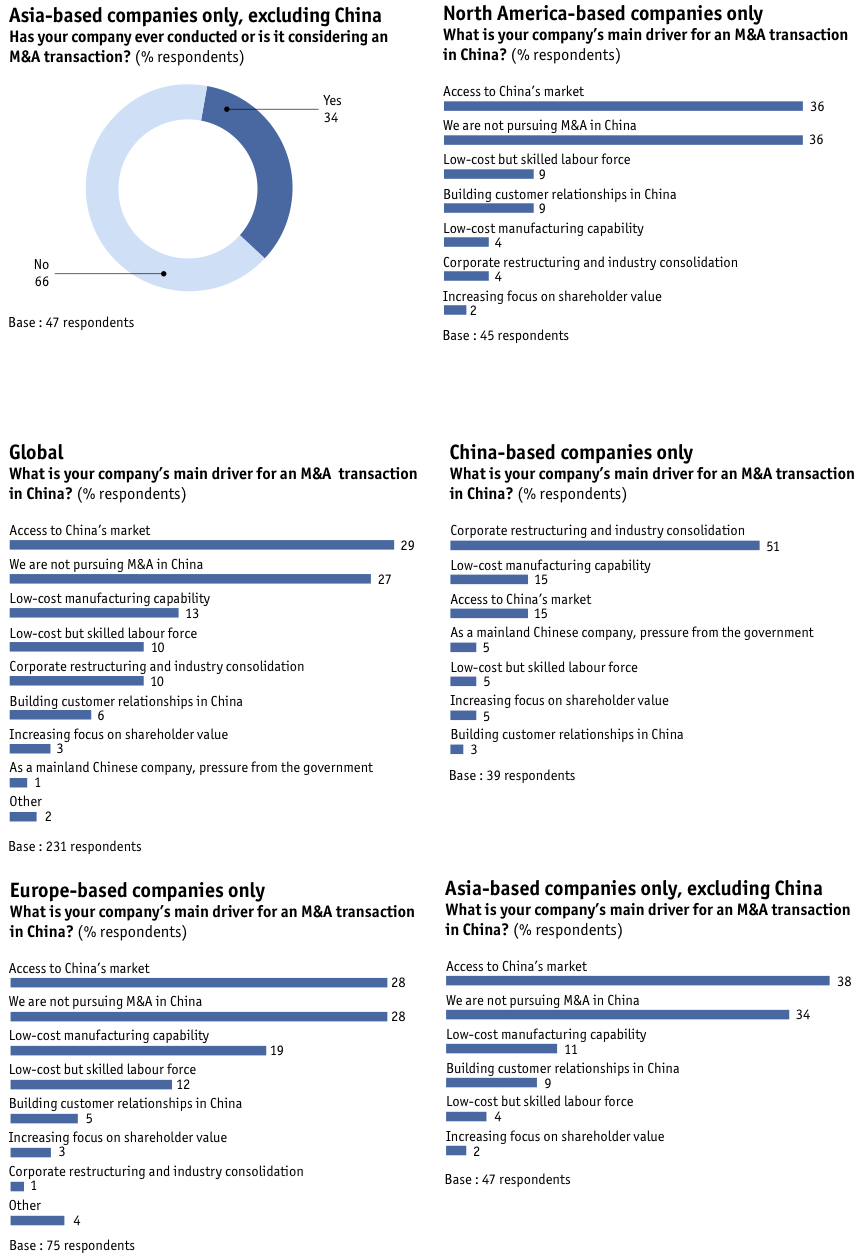

But then these foreign buyers are strategic investors, not private-equity and portfolio managers intent on turning a profit at the shortest possible time. In our survey, a third of respondents from North America and Asia, and 28% from Europe, say the main driver for their company’s M&A activity in China is to gain access to the domestic market. Less than 3% cite as a motive the desire to increase shareholder value, at least initially—seven out of ten do say that the ultimate success of a merger should be measured by its effect on profits. A 20% stake in a mega-bank typically gives the foreign acquirer just one board seat, not enough to exert significant influence on strategy and control over operations.

Still, a minority stake can provide the foreign acquirer with a valuable asset, at least on paper. Bank of America paid US$3bn in 2005 for 8.5% of China Construction Bank, the mainland’s fourth-argest lender in assets, which works out to about HK$1.20 (15 US cents) per share. The initial public offering was priced at HK$2.35 in December that year, immediately giving Bank of America a 96% return on its investment. The stock reached HK$3.85 at one point in February 2006, valuing Bank of America’s stake at HK$73.6bn or US$9.5bn—a paper gain of 217%.

Of course, the stock price would crater if China Construction Bank were to fail to deliver on the great expectations. In any case, Bank of America cannot cash in on its paper profits now because of a three-year lock-up. Not that it wants to. The bank has the option to increase its holdings to 19.9% within the next five-and-a-half years. It can buy more if the government ever decides to increase the limit on bank foreign ownership. “A minority stake should place the investing bank in a prime position to increase its stake when, and if, the market fully opens,” says Standard & Poor’s, a credit-rating agency, in a recent report.

And even a minority stake can give a foreign investor access to an existing customer base and product range, knowledge of the Chinese market and lower regulatory risk. Royal Bank of Scotland is buying 5% of second-largest lender Bank of China for US$1.6bn. Part of the agreement is the formation of joint ventures in retail-based businesses such as credit cards and personal insurance. Thus, apart from possible paper profits on its stake when Bank of China lists in Hong Kong later in 2006, Royal Bank of Scotland could potentially leverage on Bank of China’s 80m holders of debit and credit cards, and more than 11,000 branches and offices nationwide.

Foreign strategic investors have had more luck taking outright control of businesses deemed not as sensitive as banking, such as hotels, fast-food chains and breweries. The leading example here is Anheuser Busch of the US, which paid US$765m to acquire Harbin Brewery (see case study in Outlook). Anheuser had figured in a bidding war with South Africa’s SABMiller, which had owned 29.4% of Hong Kong-listed Harbin. SABMiller had failed to secure an additional 29% stake in Harbin that was owned by the Harbin government.

This 29% was sold by the government to an investor group, rather than SABMiller, and was subsequently bought by Anheuser Busch. SABMiller then offered to buy the shares held by the public for HK$4.30 a share, but Anheuser countered with a much higher offer of HK$5.58. SABMiller decided to sell its stake, pocketing a profit of US$124m (a 143% gain on its original investment of US$87m made only 11 months earlier) that later came in handy when its joint venture with conglomerate China Resources paid US$154m for Lion Nathan’s Chinese breweries.

Some analysts say that Anheuser overpaid, but the company insists that the price was worth it for the synergies it expects from the purchase. Harbin’s Hapi brand, which has 30% of northeast China’s beer market, complements Anheuser’s super-premium Budweiser beer and premium Tsingtao (Anheuser has a 27% economic interest in Hong Kong-listed Tsingtao Brewery). Anheuser plans to use Harbin’s distribution and sales network in the northeast to strengthen the market positions of the Budweiser and Tsingtao brands there. Spanning as they do the entire beer-drinking price spectrum, the three brands are also expected to help each other in strengthening their respective market shares nationwide.

Other notable foreign-domestic deals include Emerson Electric’s US$750m purchase of 100% of Avansys Power from Huawei Technologies in 2001, Mittal Steel of India’s US$338m acquisition of 36.7% of Hunan Valin Steel Tube and Wire in 2005, and eBay’s US$150m takeover of eachnet.com in 2004. The flashiest M&A announcement in 2005 was Yahoo! Inc’s US$1bn acquisition of a 40% economic interest (with 35% voting rights) in e-commerce portal Alibaba.com. The range of sectors and players involved in these deals attests to the widening breadth of foreign-domestic M&A in China.

• Domestic strategic investors. Local companies, too, have not shied away from M&A (see table Home shopping). At US$53.6bn, Hong Kong-listed China Mobile’s series of purchases from 1998 to 2002 of the mobile-phone networks of its parent, China Mobile group, is the biggest-ever local M&A deal, followed by another telecoms transaction, that of China Telecom’s US$9.7bn acquisition in 2003 of the provincial fixed-line networks of its parent, China Telecom group.

The two acquisitions are examples of how SOEs go about getting listed. First, they inject their most profitable and cleanest assets into a new enterprise that will then go public. In subsequent years, the listed subsidiary uses its growing financial muscle to buy the rest of the assets from the parent. Because it is listed, typically in Hong Kong and often in New York as well, the subsidiary strives for transparency and arm’s length valuation in the M&A task of gutting its parent. Private-sector companies are now beginning to join the party. In February 2006, Hong Kong-listed Wumart Stores, the largest supermarket chain in Beijing, agreed to buy 75% of tiny Beijing’s MerryMart Chainstores for Rmb370m (US$36m). The acquisition helped to make Wumart even further ahead of rival Carrefour of France, Beijing’s second-largest chain. “We are now triple the size of the No 3 operator [Tiankelong],” Wumart’s chairman, Zhang Wenzhong, told reporters in March 2006. Wumart intends to squeeze more benefits from the purchase by introducing new information technology (IT) and management systems designed to enhance efficiency in operations and to strengthen cost control.

Another example is Target Media’s merger with Focus Media in January 2006. This particular deal was driven in part by private-equity investors that worked for months to nudge the founding entrepreneurs into the M&A, particularly The Carlyle Group, which has invested in Target Media. “It was 60% economic logic, 20% the trust that the entrepreneur had in us, and another 20% the consensus of other stakeholders [in both companies] who felt the same way and who were supportive,” says Wayne Tsou, Carlyle’s managing director for the Asia Growth Capital team.

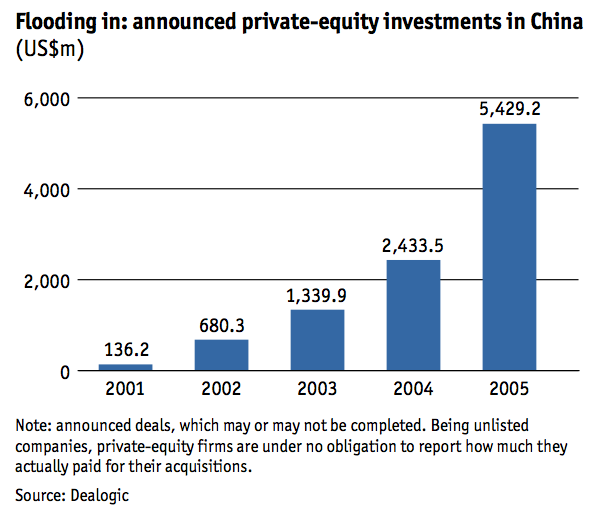

• Private-equity investors. Mr Tsou believes that M&A in China will continue to surge, prodded in part by private-equity stakeholders like Carlyle. These financial investors are getting more involved in China. According to Dealogic, also a global provider of financial information, announced private-equity investments in the mainland have made a spectacular jump from just US$132.6m in 2001 to US$5.4 bn last year (see Flooding in).

Unlike strategic investors, most private-equity firms have a set time limit to exit their investments in order to realise profits for their investors—or to cut their losses, if the problems at the invested company prove intractable. They are in a hurry to enhance shareholder value by raising capital, squeezing efficiencies through improved financial, operational and IT management, growing revenue by brokering relationships among the companies they have stakes in—and these days, pushing inorganic growth, such as the Focus-Target merger.

Almost all the world’s major private-equity firms are now in China. They include Carlyle, International Finance Corporation (IFC, the private-sector arm of the World Bank), Newbridge, Temasek Holdings (Singapore’s government-linked investment company), Warburg Pincus, 3i and specialist players like Peak Capital. During the technology craze of the late 1990s, private-equity players were throwing money at anyone in China with a seemingly bright idea. They are more selective today, but are looking at every industry and company needing venture capital (for start-ups), growth equity (for mid-stream targets) and buy-out funds (for mature enterprises).

Private-equity deal sizes are growing larger, led by deep-pocketed Temasek (see Private money), and in the last two years, increasingly targeted at mature companies, including state-owned enterprises. Carlyle’s 24.9% investment in 2005 in No 3 insurer, China Pacific Life Insurance, in partnership with US insurer Pramerica Financial, is a case in point. The deal is notable for the remarkable concessions Carlyle and Pramerica extracted from the state-owned enterprise, including four board seats, veto power over key decisions, and the right to appoint the chairman of the management committee, chief actuary, chief investment officer, chief audit officer and other managers.

For Sinotrans, M&A is a way to become competitive

Sinotrans has hardly been monogamous. The Hong Kong-listed arm of Sinotrans Group, a Chinese state-owned enterprise, Sinotrans has partnered some of the best and biggest companies in express mail and freight forwarding: UPS, DHL and TNT among them. The relationships started mainly because foreigners earlier could only enter China’s logistics and distribution business through partnership with a local company.

Although China’s entry to the World Trade Organisation has eased regulations for foreign multinational companies, domestic companies in the meantime have learned from their international partners and want to develop their own muscle. Many, including Sinotrans, plan to do this through mergers and acquisitions (M&As). Notes Zhang Jianwei, president and executive director of Sinotrans: “Our goal is to increase our competitiveness and market share, so we will use M&A to increase our chances of being competitive.”

According to Mr Zhang, the most important development will be in logistics. Sinotrans has already increased its capacities in freight forwarding (air and ocean), shipping agency, express mail, warehousing and terminal operations including regional distribution centres (freight stations and freight yards), and plans to move forward more quickly in the next three to five years.

To beef up its distribution network, Sinotrans wants to buy an air carrier. All major courier services already have numerous flights to China, as well as strategic partnerships to handle internal flights. But Sinotran’s bid for Sichuan Air, a domestic carrier, late in 2005 did not work out, and Mr Zhang says the company is “still looking at domestic targets, and possibly international targets”— a hint perhaps that Sinotrans may well be China’s next conglomerate to look at conducting M&As overseas.

According to the Sinotrans president, the company has become more competitive since listing in Hong Kong in early 2003. Systems have been reorganised to allow for procedures such as performance reviews and incentive schemes, previously difficult processes to introduce in a state-owned enterprise. These changes allow senior managers and employees to focus on creating shareholder value. “Now lots of investment banks are approaching us about potential targets,” says Mr Zhang. “We’re thinking about those.”

Meanwhile, Sinotrans remains a strong partner for many foreign logistics companies. DHL-Sinotrans, DHL of Germany’s joint venture with Sinotrans, does not come up for contract renewal until 2036. DHL is a shareholder in the listed company.

Sinotrans’ other long-term partner was UPS, with whom it started co-operation in 1988, at a time when joint ventures defined the main way for foreign companies to do business in China. “Companies had to have a partner to enter China, and because of our status and strong government backing, Sinotrans was the first choice,” says Mr Zhang. In 2005 UPS bought out its 23 joint ventures with Sinotrans for US$100m.

To Mr Zhang, this stage of development is part of Sinotrans’ history. “Because of China’s regulations on courier services, UPS had to use a partner. But UPS’ s own strategy is to develop on its own,” he says, explaining why the relationship with UPS ended.

The targets

China Pacific Life’s concessions illustrate the eagerness of potential Chinese target companies for foreign capital and expertise, and their increasing willingness to bite the bullet in order to attract acquirers. Earlier, China Pacific had spent two years negotiating with Australian insurer AMP, which eventually made an offer but then abruptly withdrew it in 2001. Carlyle signed a memorandum of agreement in 2003, spent four months on a comprehensive due diligence, and then presented China Pacific with a restructuring proposal. The two parties signed a definitive agreement in April 2004, but the deal looked on the verge of collapse when media reports circulated about disagreements over pricing and other fundamental issues.

Carlyle sought to bolster its bid by bringing in Pramerica, possibly the first time in China that a private-equity firm teamed up with a strategic investor to win a deal. That was the cue for various other strategic investors to make their own bids. But Carlyle and Pramerica prevailed. The agreement provided for a top-to-bottom revamp, from standardisation of recruiting procedures to adjustment in the product mix to centralisation of the IT, finance, underwriting and claims systems to the implementation of control and risk management mechanisms. China Pacific also agreed to sell up to 49% of the company to Carlyle and Pramerica if the regulations were changed to allow it.

While some potential targets like Yangzhou Auto Plastic Parts are saying no (see case study), Chinese companies operating from a position of weakness are proving receptive to M&A overtures from both foreign and domestic suitors. These include SOEs like China Pacific Life that had built up market share in a protected environment, and now run the danger of losing it as their industry is opened to real competition; those in fragmented industries like steel, coal and cars, and thus under pressure from Beijing to merge; and provincial and township enterprises aiming to monetise future cash flows by bidding out concession rights to the toll roads, bridges and other infrastructure they had built.

For domestic acquirers, the main objective of M&A appears to be to gain market share or fulfil a business strategy. Focus Media’s acquisition of Target Media and the ongoing deal with Framedia will increase its market share of the relatively new advertising sector of lifestyle media, advertising posters and LCD monitors placed in commercial and residential buildings to over 90% in Shanghai. For large SOEs like Sinotrans, M&A primarily serves operational growth. Sinotrans reports that its acquisition of container ports in China is likely to increase over the next three to five years in pursuit of its freight forwarding business objectives.

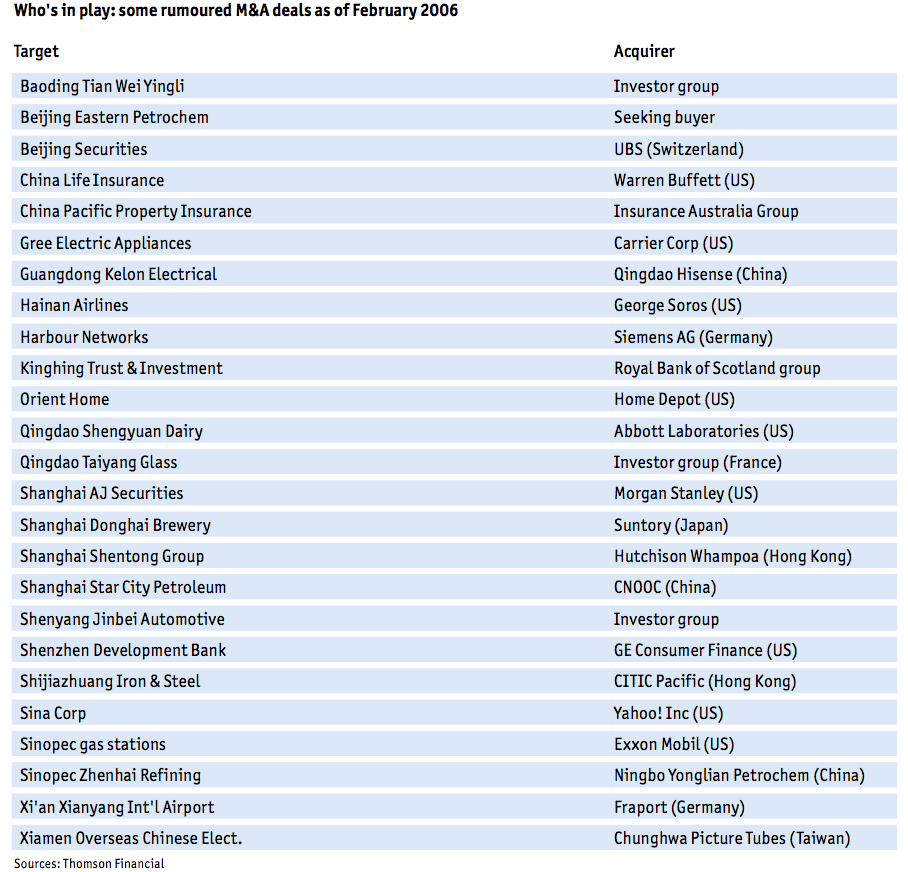

Tracking talk of M&A deals in China, Thomson Financial has compiled a list of supposed targets (and their purported acquirers) from 1993 onwards. The rumour mill started to churn faster in 2003 and has not stopped since. So far in 2006, ten deals were rumoured, with one, Singapore bank OCBC’s purchase of 12.2% of Ningbo Commercial Bank, confirmed in January. (Some recent rumours are shown in Who’s in play.)

TCL and Lenovo: two for the world

Spare a thought for TCL Multimedia Technology’s long-suffering shareholders. When the Hong Kong-listed mainland Chinese electronics maker took over the television (TV) assets of French conglomerate Thomson in 2004 to form a new company called TTE, its stock price soared on optimism that it could extract more value from Thomson’s brands, which included the venerable RCA trademark in the US. TCL boldly promised to turn around TTE’s money-losing North American operation by the second half of 2005.

That didn’t happen, however. TCL then set the first quarter of 2006 as the new target for the recovery. Even that is looking iffy. In February 2006, TCL issued a profit warning on its 2005 results. In a statement, chairman Li Dong Sheng said that the company “will not meet its expected performance target” for last year because of TTE, but did not give financial details. On March 8th 2006, TCL’s share price closed at HK$1.14 (about 15 US cents), down 53% from what it was before it acquired Thomson.

Investors in Chinese computer maker Lenovo, which bought the personal-computers (PC) division of American icon IBM in May 2005, are doing better. As it happened with TCL, Lenovo’s share price surged on the news of the takeover. The optimism reached a high point in December 2005, when it looked like Lenovo would report solid third-quarter numbers. The stock price reached HK$3.90, jumping 50% from its pre-acquisition level. In January 2006, Lenovo said its third-quarter earnings were up 12% year on year. But worryingly, gross profit margins fell by nearly a percentage point to 13.2%, continuing a trend that began in the second quarter. The stock closed at HK$3.025 on March 8th 2006, still 23% higher than before the IBM acquisition but lower than its peak in December.

Similar, but different

Two companies, one goal—to become a Chinese multinational company. Both TCL and Lenovo have opted to take a short cut to the global stage through a merger and acquisition (M&A), not through time-consuming organic growth. Both are counting on their economies of scale, super-efficient factories inside and outside China, and lean supply chains to squeeze manufacturing costs, allowing them to sell the established brands they had acquired at fatter margins. And both retained most of the target-company’s senior management, resisting the urge to replace them with Chinese executives.

So why is TCL stumbling while Lenovo appears to be faring better?

One reason is the quality of the acquired brands. “We thought we could sell RCA as a premium brand, but in fact it had already deteriorated into pretty much a low-end brand,” Vincent Yan, managing director of TCL Multimedia, told CFO Asia, a sister publication of the Economist Intelligence Unit, in 2005. As a result, TTE did not have pricing power, negating the lower costs achieved by exercising its greater clout in sourcing materials and rationalising its two parents’ production bases and marketing networks. “Moving a brand up is extremely difficult in North America, and we’re not sure that’s the way to go,” Mr Yan said. “It’s always possible to introduce Thomson, TCL or another brand [as a premium name in the US], but it would be risky.”

By contrast, the IBM brand, particularly the popular ThinkPad, had not lost its lustre. This allowed Lenovo to raise selling prices while cutting manufacturing costs, thus turning around the previously ailing operation. But the fall in gross profit margins highlighted a weakness. IBM had no product for small-to-medium enterprises. “As a result,” Lenovo’s chief financial officer, Mary Ma, told reporters in January, “we had to offer higher-end products at the lower-end segment of the market, and compete there on price.” The home-grown Lenovo brand is more affordably priced, but is sold only in China and the rest of Asia.

New directions

That all changed in February when Lenovo introduced low-priced Lenovo-branded desktops and notebooks to the US and other Western countries. The new strategy was unveiled shortly after William Amelio was named chief executive officer to replace IBM veteran Stephen Ward. Mr Amelio was previously a senior vice-president at Dell, the world’s largest computer maker with 17.2% of the global market, miles ahead of Lenovo’s 7.2%. Mr Amelio is expected to apply Dell’s approach of squeezing savings from all aspects of its business. He has already declared war on operating expenses, which had ballooned in the third quarter to 11.5% of sales from just 6.9% a year earlier. “We have to unplug from the legacy system and cost structures that we are part of right now,” he declared. In its first major restructuring since Mr Amelio took over, Lenovo in mid-March 2006 announced that it would fire 5% of its staff (or 1,000 employees) and shift some offices. The measures are reportedly expected to save Lenovo US$250m annually.

TCL has yet to shake up TTE’s management—Al Arras, who headed Thomson’s television division, remains president—but it has moved to unplug the new company from Thomson’s legacy systems, too. TTE has taken over sales and marketing activities in Europe and North America, which were previously subcontracted to Thomson. It has also amended a service contract with a Thomson television-manufacturing facility in France to improve its cost structure and thus enhance price competitiveness in Europe. The best solution is to source from much cheaper eastern Europe, where TTE has its own facilities, but a clean cut from Thomson’s French factories is apparently too drastic a move at this time.

TCL is also retaining TTE’s multi-brand strategy, which means virtual silos of the different brands—RCA in North America, Thomson in most of Europe, Schneider in Germany, TCL in China and the rest of Asia. For now, TCL has apparently decided the way to go is to rehabilitate the RCA brand, rather than position its other brands in the US’s premium segment. It recently unveiled a new line of 50-inch and 60-inch high-definition TV models under the RCA Scenium brand in the US. In February 2006, TTL signed a strategic alliance with LG Philips in the fast-growing Thin Film Transistor Liquid Crystal Display TV segment.

Time will tell whether Lenovo and TCL will achieve their global ambitions. What is clear, though, is that buying consumer brands that their original progenitors no longer want is the easy part for Chinese companies. The hard part is making all the complicated pieces work on the global stage. Other ambitious would-be Chinese multinational companies would do well to watch them closely and learn.

The globalisers

One interesting finding in our survey relates to the expectations of Chinese companies gobbling up overseas assets. Only 31% of respondents from China and 43% from the rest of Asia say that China’s outward M&A activity will increase. By contrast, a high 60% of North American and 56% of European executives surveyed expect more such deals. Who’s right? As in the hysteria over Japan’s supposed corporate raid of Western assets in the 1980s that did not really happen, it may be that the West is once again getting its back up over nothing much.

The exaggerated expectations (and fear) have been fanned by the high-profile forays in the last two years of would-be Chinese multinationals like Lenovo and oil firms such as CNPC and CNOOC (see Stepping out). With more than US$800bn in foreign-exchange reserves, goes the theory, China can finance any number of corporate takeovers of the world’s best and biggest companies in its quest to become the world’s next superpower.

This is nonsense, of course, and ignores the reality that there is much more to M&A than simply throwing money at foreign targets. TCL of China is not exactly experiencing a smooth ride after swallowing the television operations of Thomson; Lenovo is doing a bit better, but it too is meeting problems (see case study, Lenovo and TCL: two for the world). As mentioned earlier, China’s corporate management bandwidth is still far too limited, and its companies themselves know they are not ready for the prime time. The likes of General Motors, Microsoft, Citigroup and Sony have no cause for worry from Chinese takeover artists for a long time yet.

YAPP: the one that got away

Yangzhou Auto Plastic Parts (YAPP) decided to just say “no”. Despite its clear ambitions to become a multinational entity, in early February 2006, YAPP turned down a takeover bid from Paris-based Inergy Automotive Systems after nearly three years of negotiations.

Inergy had wanted to buy 55% of YAPP, China’s largest producer of plastic automotive fuel systems, from its majority shareholder, the State Development Investment Corporation (SDIC), China’s largest state-owned holding company. But takeover rules in China governing state-owned enterprises require an employee vote prior to approval of an acquisition by the board of directors and shareholders. YAPP employees apparently nixed the bid.

The reasons why the employees vetoed the acquisition were not disclosed. Perhaps the price was not right. But it seems more likely that management and staff believed that YAPP’s strategic plan to expand in Asia-Pacific on its own had more business potential than becoming a mere manufacturing arm to a multinational company. “Our basic objective is to establish plants in Thailand, to support some of Ford’s manufacturing facilities, and India,” says Sun Yan, president of YAPP.

Indeed, the company has the advantage of a strong base of multinational customers and suppliers, and well-placed domestic shareholders. Besides SDIC, which holds a 66% stake in YAPP, the other shareholder is Shanghai Automotive Investment Corporation, Shanghai’s automotive jewel, which holds the remainder. Most importantly, automotive remains a key national industry for China, and is both protected and promoted by the government. This bodes well for YAPP’s plan to become an international name and to make its fuel tanks an international brand.

Yapp’s refusal to accept Inergy’s acquisition bid is not as significant a step for one company as it is an indication of changes in the market, cautions one Shanghai-based automotive industry analyst: “Introducing a foreign partner to local enterprises is no longer the only way [for domestic companies] to get bigger and stronger.”

Traditionally domestic Chinese companies have looked to joint ventures or mergers as a way to acquire much-needed technology and newer management techniques. But nowadays, particularly in highly competitive industries, there are other options such as licensing agreements, strategic partnerships and purchases of imported machinery involving training courses.

Many successful domestic companies can now afford to spend on expensive consulting advice and training programmes, and thereby ease their management and technology shortfalls.

YAPP’s president acknowledges that technology was the main reason the company had considered the Inergy acquisition. But now it wanted to use a different approach to solve technology issues. “We have lots of co-operation with multinationals, and YAPP’s development has been very fast,” says Mr Sun.

Development initiatives include the scheduled opening of a research and development (R&D) centre at the Yangzhou headquarters in mid-2006.

Mr Sun adds that the company plans to invest a total of Rmb400m (US$49.7m) over the next five years on development; one-fourth of that amount would be on new R&D capabilities, including the Yangzhou centre. Also on the cards are joint ventures in Thailand and India to establish production facilities in those countries. According to Mr Sun, YAPP has already signed a technology-support agreement with Zoom Automobile Ancillaries of India, as a precursor to establishing a joint production facility.

What next for YAPP

And what about Inergy? For the French company, the acquisition of YAPP, due to be complete by end-2005, had been part of its plan for rapid expansion in Asia-Pacific.

Through YAPP, it had hoped to attain an immediate market share in China of over 30%, a customer base that included all major automotive manufacturers in the China market, and manufacturing or assembly facilities in all of China’s automotive centres: Shanghai, Wuhan, Changqun, Chongqing, Yangzhou, Wuhu, Tianjin and Shenyang.

Entering China with a stable production volume would have saved time and costs. YAPP and Inergy had worked together on projects since 2001 and began talking about acquisition in 2003. Negotiations finally led to the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding on January 20th 2005 for the acquisition of YAPP. Now that the deal is off, Inergy is considering establishing wholly owned facilities in China, but it hasn’t ruled out looking for other acquisition targets.

Chapter 3

On the ground: survey results

The world is looking at China—as a huge market of 1.3bn people and boundless opportunity in which to sell, buy and indeed invest. Ever since the first merger-and-acquisition (M&A) transaction was completed in China in 1985, the country has risen in prominence as both a target and an acquirer. From just US$124m in completed M&A deals involving China in 1985, the figure jumped to a record US$28.5bn in 2005, making China the largest M&A market in Asia after Japan and Australia, and nudging South Korea out of the No 3 spot.

How will the heightened M&A activity affect businesses in China, the rest of Asia and the world? Where are the fresh opportunities for foreign companies? What are the pitfalls for acquirers in China? Why do Chinese companies look to buy overseas and what are the assets they want to pick up?

The great buy-out: M&A in China aims to answer these questions. There are many things to see in aggregate numbers and big-picture trends, but nothing beats an on-the-ground look. The Economist Intelligence Unit conducted a survey in January and February 2006 of 231 companies in China and the rest of the world, questioning them about their M&A intentions, activities and experiences. The study also includes in-depth interviews with acquirers and target-companies, (including one that got away), Chinese regulators, investment bankers, management consultants, private-equity investors, lawyers and others engaged in the M&A process.

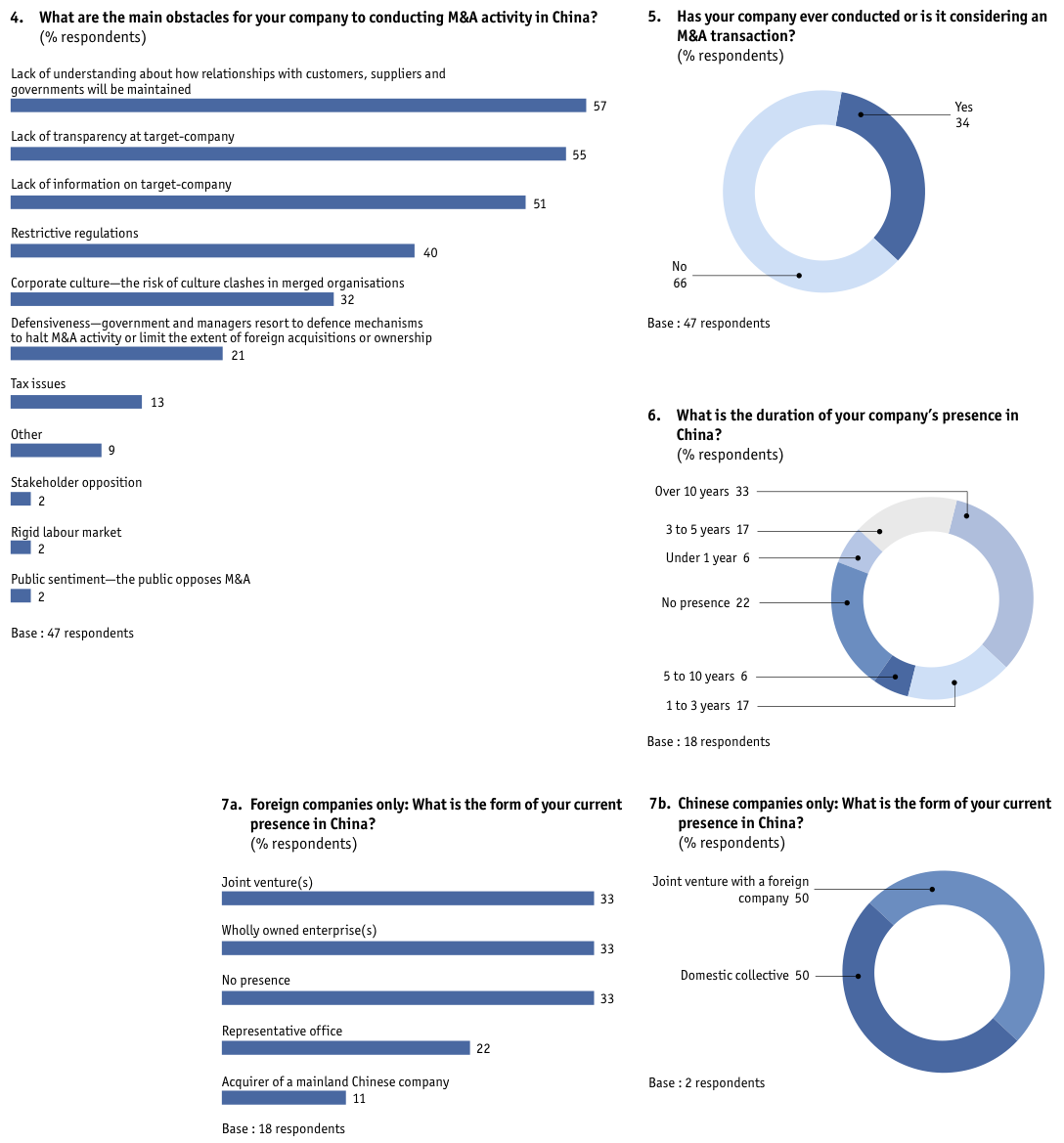

The heart of this white paper is the survey. The questionnaire tries to assess the main drivers of companies’ equity investments in China, and what the key factors are in their decisions when identifying an M&A target. It also examines what the main operational issues are for an acquirer taking over a mainland Chinese company: is it difficulty in conducting due diligence on the target, incomplete or inaccurate asset valuation or fraudulent asset valuations?

To enhance the findings of the overall global survey, the results are also segmented along geography. Hence, we can see what only China-based respondents think about the same issues; and in the same way, the responses in Asia-Pacific, excluding China; in Northern America and in Europe. The complete results for the global survey, as well as the geographical segments, are in the Appendix. The analysis in this chapter makes comparative use of the different survey results.

Demographics of respondents

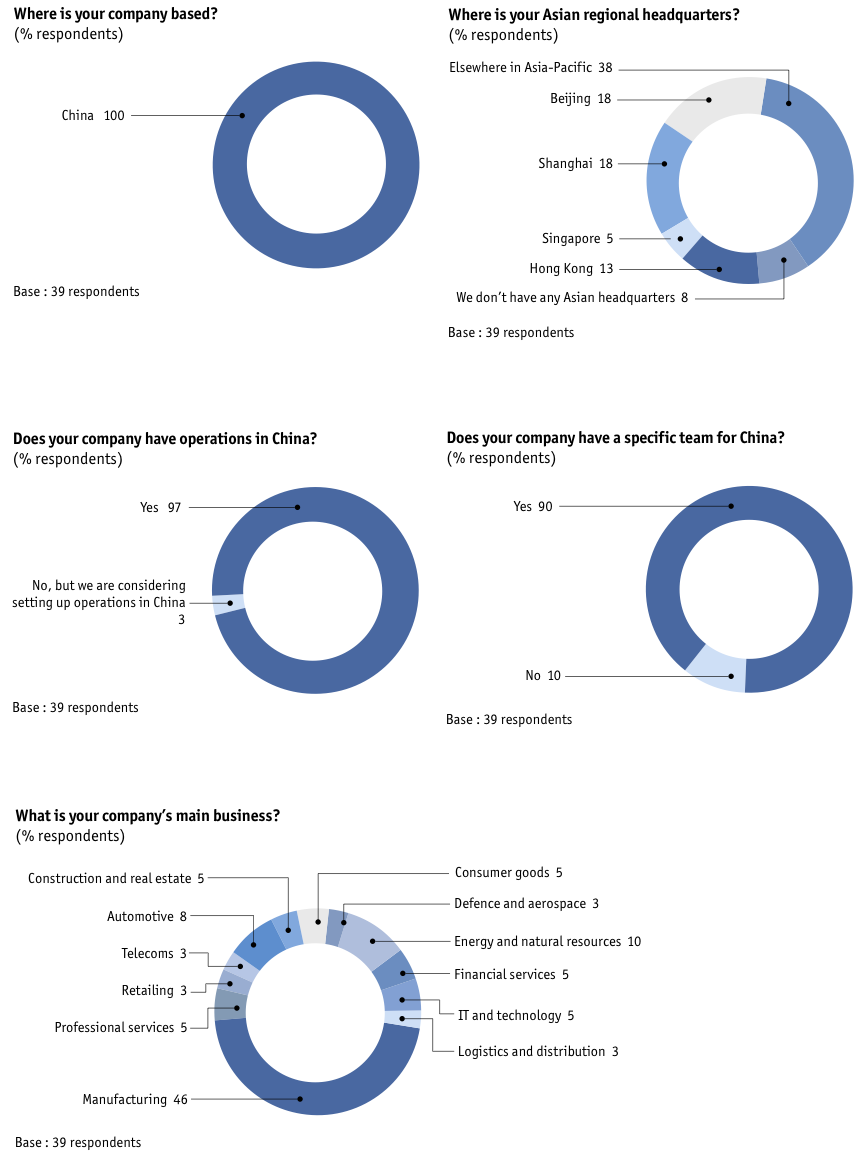

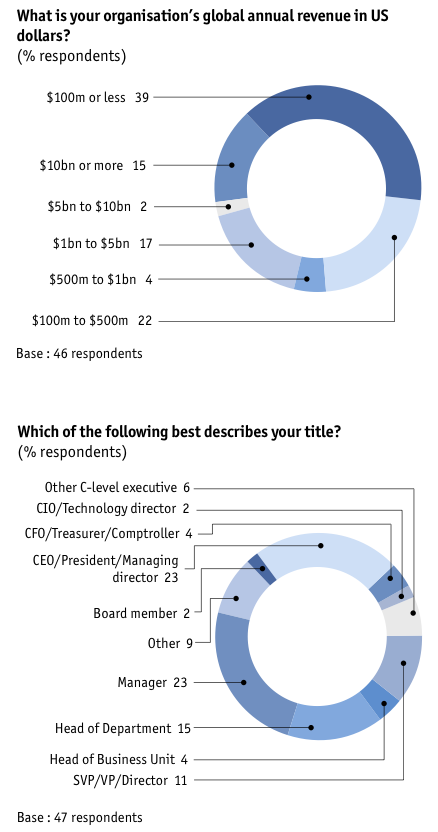

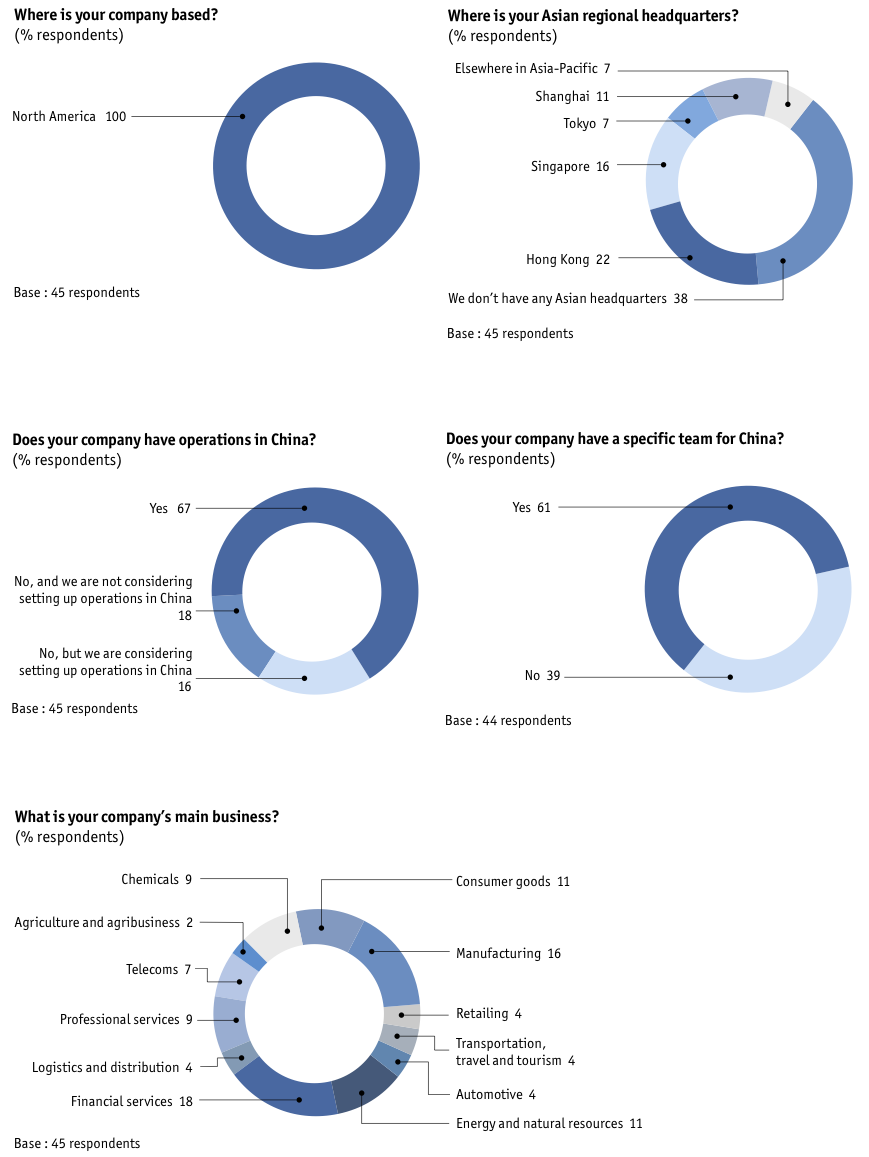

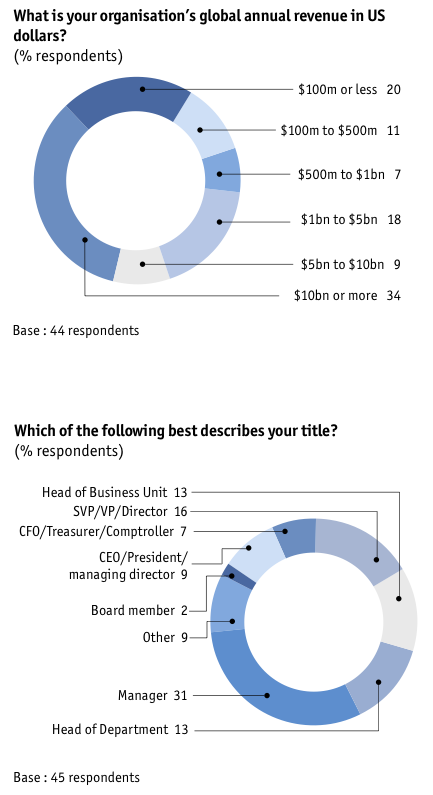

The global survey drew a total of 231 respondents from among board members, chief executives, chief financial officers and other C-level executives. They are from companies in China (17%), elsewhere in Asia (20%), North America (20%) and Europe (33%). They operate in a variety of industries from manufacturing (16%) to financial services (13%) to professional services (9%) to consumer goods, and information technology and technology (both 8%).

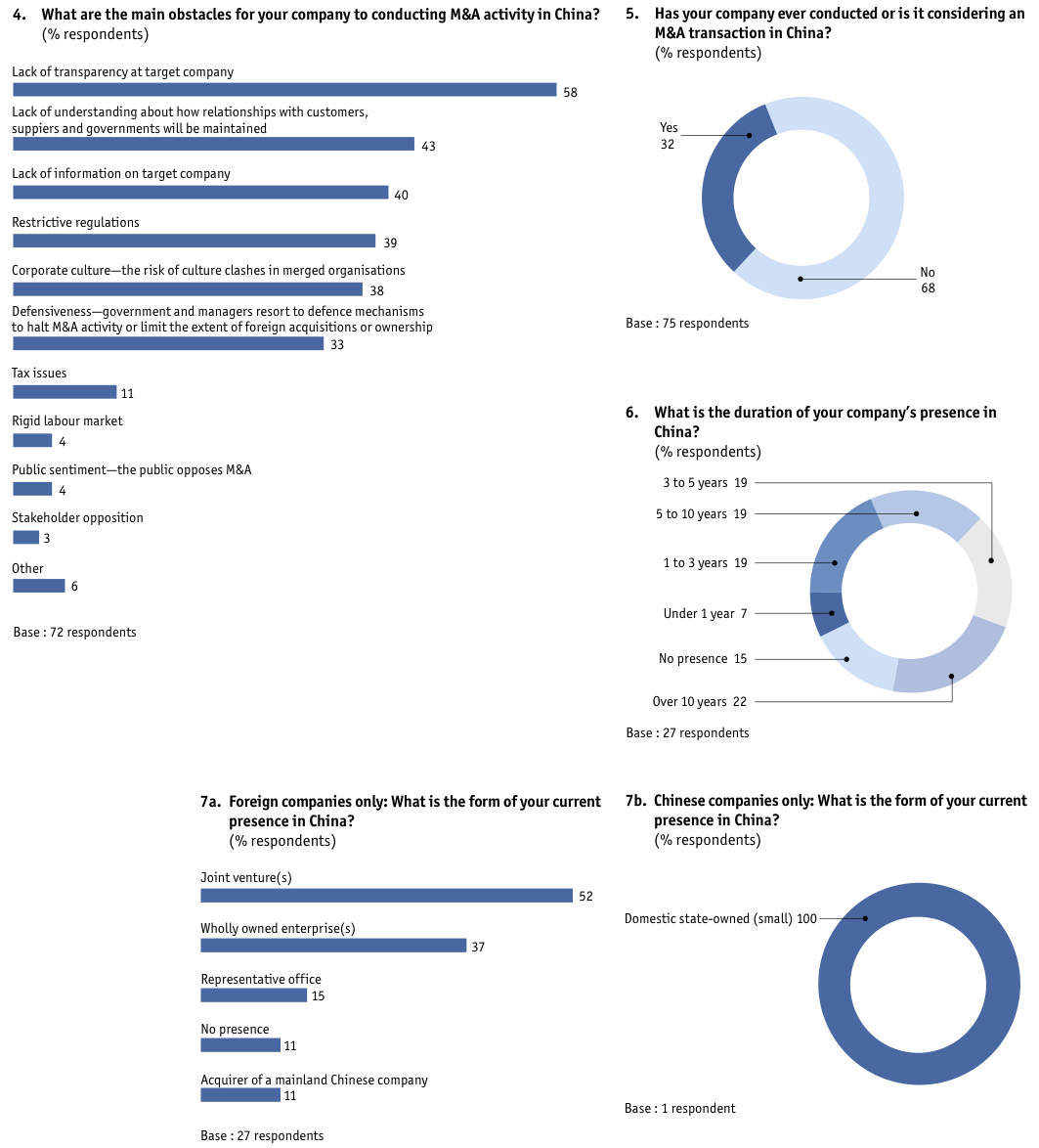

The overwhelming majority of companies either have operations in China or are considering setting up there: 82% of respondents from North America, 71% of those from Europe and 65% from Asia, excluding China. More than half of total respondents (55%) have had a presence in China for at least five years; four out of ten have been operating there for more than a decade.

Most of the early settlers come from North America—45% of executives surveyed from that part of the world say their company has been operating in China for at least ten years. A third of respondents from Asia, excluding China (33%), say the same. The laggards are companies from Europe, where only two of ten companies (22%) have been operating in China for ten years or longer.

The majority of the non-Chinese companies in the global survey currently have a presence in China in the form of a joint venture (46%) or a wholly owned enterprise (38%). Only a few have been an acquirer of a mainland Chinese company: 11% each of respondents from Asia, excluding China, and Europe; and 9% from North America.

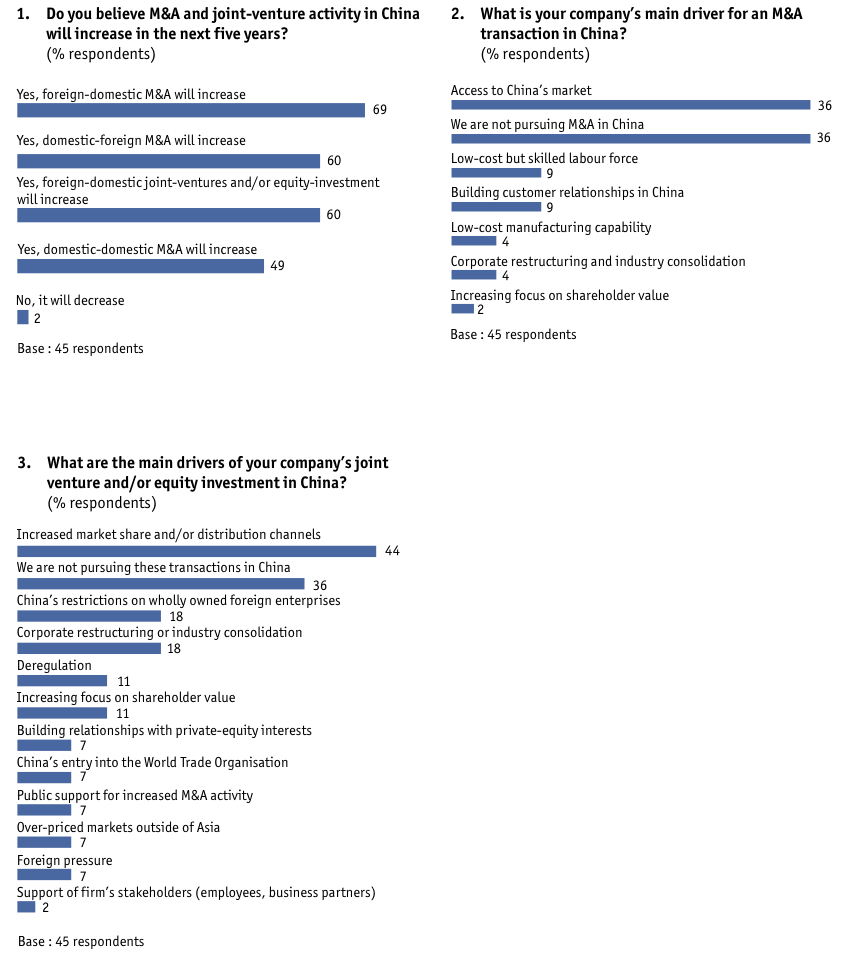

Trends in M&A activity

In the global survey, 43% of respondents agree that their company has conducted or is considering conducting an M&A deal in China. If you take out the Chinese companies from the equation, at least three out of ten respondents also answer in the affirmative. More than half expect foreign-domestic M&A in general to accelerate, particularly respondents from Europe and North America (both 69%).

Domestic-domestic M&A in China will climb even higher. An overwhelming majority of respondents from China only (90%) say their company has conducted or is considering conducting an M&A transaction. And six of ten expect domestic-domestic M&A transactions to increase. The momentum is evident in the recent merger of Focus Media and Target Media (see case study).

Why is M&A activity across the board accelerating? Access to China’s market is the key reason given by 29% of respondents to the global survey. This is also the reason cited by 38% of companies from Asia, excluding China, alone; and by 26% of respondents from North America alone. More Europeans cite low-cost manufacturing capability as an M&A driver (19%) than do respondents from North America (4%), an indication that Europe is playing catch-up with the US in using China as a cheap production base for exports. Having set up operations earlier in China, North American firms are now looking at the mainland as a market in its own right, while the relatively laggard Europeans have yet to get to this advanced stage. Among Chinese companies only, the overwhelming reason to participate in an M&A transaction is to respond to corporate restructuring and industry consolidation (51%). Government pressure is a minor driver (5%).

Focus buys Target, Framedia; Framedia does its own deals

If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. That adage could certainly be applied to the decision to merge by Focus Media and Target Media. The two mainland Chinese advertising companies were fierce rivals ever since they both started out in mid-2003 to develop what they called the “out-of-home advertising network”. But on February 28th 2006 they officially joined hands—Focus Media bought Target Media for US$94m and 77m Focus Media ordinary shares, according to information filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. David Yu, Target’s former chief executive, was appointed co-chairman and co-president of Focus Media.

As analysts see it, the acquisition will help both companies because they can now take on others instead of each other. Even in China, famed for its massive building boom over the last decade, the number of commercial and residential buildings remains limited. Shareholders and management of Focus Media realised that two strong competitors in the limited market would mean advertisers could cut fees, while building owners could raise rents—a disastrous combination for the earnings of the fledgling companies.

So it was that after three years of intense competition, Jason Jiang, founder of Focus Media, and David Yu, founder of Target Media, agreed to merge. Focus Media’s investor relations manager, Chen Jie, says the two entrepreneurs met just three times to put their plan into action. “The merger will benefit the industry, making growth of lifestyle-media more stable,” she says, adding that absorbing Mr Yu into Focus Media gives the company another entrepreneurial senior manager to assist in strategic acquisitions that were initiated in 2005, and others that are still being planned. Ms. Chen doesn’t believe Focus Media will face any anti-monopoly problems because even after the acquisition of Target, its share of the total national advertising market is less than 1%.

The merger-and-acquisition (M&A) transaction was not without hiccups. Due diligence of Target proved a sticky issue, because Target refused to divulge all of its operational and financial issues pre-merger (perhaps prudently fearing the consequences should the M&A deal fail). Focus agreed to rely on audited financial information and market statistics provided by Target. For Focus, the risk was apparently worth taking in order to increase its market share in most cities. Post-merger, Focus will think about integration issues, but the two companies’ similar operational structures should make this a fairly straightforward exercise, says Ms Chen.

Indeed, Focus and Target have followed similar paths in their short histories, although, according to Ms Chen, Focus ended up with more market share than Target Media. In Shanghai alone, she says Focus had a 70% market share, while Target Media, the No 2 player, had 20% as of end 2005.

By late 2004, the Shanghai-based competitors both began looking at an initial public offering (IPO) as a way to obtain cash to spur the growth of their businesses. Both companies had attracted venture capital since start-up: 3i in Focus and The Carlyle Group in Target, and had restructured through opening holding companies in the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands in preparation.

But Focus got off the block first, listing on Nasdaq in July 2005. (The venture capitalists played a role in arranging the Focus-Target marriage, according to Wayne Tsou, Carlyle’s managing director for the Asia Growth Capital team.)

Focus Media also buys Framedia

After its IPO, Focus Media acquired two smaller competitors in southern China, and began looking at other possible strategic acquisitions. One target was Beijing-based Framedia Advertising, which specialised in placing poster frames for ads in elevators. Framedia and Focus Media had some natural synergies, and Framedia’s business model and strategy fitted in well with those of Focus Media. The latter began to court Framedia even as it wooed Target Media, eventually completing the acquisition of Framedia on January 1st 2006.

Framedia had sold its LCD-panel advertising unit to Focus in September 2004 and talks on a possible merger began at that time. Tan Zhi, Framedia’s chief executive who had bought out the founders in mid-2004, wanted to consolidate the business. Like Focus Media’s Mr Jiang and Target’s Mr Yu, Mr Tan saw opportunity in the out-of-home advertising market. He also had equity investment from Hina Capital Partners and IDG Technology Venture Investment, two US-based, China specialist venture-capital firms. Similarly, he pursued strategic acquisitions and an IPO for Framedia, while also talking with Focus Media about a tie-up.

Framedia’s total valuation was set at US$183m, and Mr Tan agreed on a US$39.6m cash payment plus shares in Focus Media as a condition for the merger. Framedia comprises a separate business unit under Focus Media, and further payments were agreed on an earn-out model based on Framedia’s projected 2006 earnings.

Mr Tan is understandably pleased with the deal—he bought into the company at a valuation of only Rmb30m (US$3.7m). Besides the acquisition price, however, he was also impressed by Jason Jiang and believed the sales-driven style of Focus Media was compatible with Framedia’s own.

Framedia made its own little deals