Introduction

The Australian tax system is subject to ongoing legislative change and contains complex rules that, together with commercial and legal considerations, affect mergers and acquisitions (M&A) transactions in Australia. Several significant developments in tax law have occurred since the last edition of this publication.

This chapter provides an overview of some of the recent developments and key Australian tax issues that are relevant for purchasers and vendors in M&A transactions in Australia.

This chapter also discusses the Australian accounting and legal context of M&A transactions and highlights some key areas to address when considering the structure of a transaction.

Recent developments

Tax reform has proceeded apace in recent years in Australia. Many of the implemented and proposed changes affect the M&A environment. The key areas of focus include the following.

On 6 November 2013, the Australian government issued a press release detailing 96 un-enacted but previously announced tax measures, indicating which will proceed and which will be subject to further consultation. Several of these measures are relevant to the M&A environment. The key measures are discussed in further detail in the section on proposed changes below.

Recently implemented changes

Anti-avoidance: The Australian government has amended Australia’s general anti-avoidance rules (GAAR), which determine whether a taxpayer obtained a tax benefit from a transaction (one of the key elements of the GAARs). The amendments do not affect the other key requirement of the GAARs that the taxpayer entered into the transaction for the dominant purpose of obtaining a tax benefit.

Transfer pricing: New transfer pricing laws were introduced with effect for income years beginning on or after 1 July 2013. The stated aim of the new laws is to modernize Australia’s transfer pricing rules and align them with international standards. As such, the rules focus on an arm’s length profit allocation, unlike the former rules, which focused on the arm’s length pricing of transactions. The new laws give the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) broader reconstruction powers where conditions between international related parties are inconsistent with conditions that would have been expected between international related parties.

Withholding taxes: The government has increased the withholding tax (WHT) rate on distributions from managed trusts to recipients in ‘information exchange’ countries from 7.5 to 15 percent.

Thin capitalization: The Australian government has announced that it will reduce the Australian thin capitalization safe harbor gearing ratio from the current 75 percent gearing ratio to a 60 percent ratio for income years starting on or after 1 July 2014.

Tax-consolidation: The government has made technical amendments to the income tax-consolidation and group restructures rules. The technical amendments aim to align these rules with other parts of the tax legislation, minimize tax consequences on genuine group reorganizations, and make other technical corrections.

Proposed changes

Earn-out arrangements: As noted later in this chapter, in earn-out arrangements, proceeds for the sale of a target include a lump-sum payment and a right to future payment, which is contingent on the target’s future profitability. These arrangements are commonly used where there is uncertainty about the value of the target (or its assets). The government has indicated that it will implement look-through capital gains tax treatment for qualifying earn-out arrangements.

Asset purchase or share purchase

A foreign entity that is considering acquiring an existing Australian business needs to decide whether to acquire shares in an Australian company and its assets. Many small and medium-sized businesses in Australia are not operated by companies; trust and partnership structures are common. In these cases, the only choice available is usually the acquisition of the business assets. For larger businesses, the company is by far the most common structure. The commentary in this chapter focuses on companies, although much of it applies equally to other business structures.

For Australian corporate groups, the distinction between share and asset transactions is largely irrelevant for income tax purposes due to the operation of the tax-consolidation rules. Generally, these rules treat a sale of shares as if it were a sale of assets. The purchaser is then effectively able to push the purchase price of the target down to the underlying assets. The distinction is more important when dealing with other taxes, such as stamp duty and goods and services tax (GST).

Hence, the decision to acquire assets or shares is normally a commercial one, taking into account the ease of executing the transaction and the history of the target.

Purchase of assets

Asset acquisitions often constitute a permanent establishment (PE) in Australia, with the assets forming all or part of the business property of the PE. Accordingly, the disposal of the assets is likely subject to capital gains tax (CGT), whereas the disposal of shares by a non-resident is not ordinarily subject to CGT.

Purchase price

The total consideration must be apportioned between the assets acquired for tax purposes. It is common practice for the sale and purchase agreement to include an allocation in a schedule, which should be respected for tax purposes provided it is commercially justifiable. There may be a tension in this allocation between assets providing a useful cost base for income tax purposes and the stamp duty payable on the acquisition.

Although there are no specific income tax rules for allocating the purchase price among the various assets purchased, it is arguable that the market value consideration provisions in the CGT rules in effect permit the ATO to determine an arm’s length transfer price different from that allocated to the asset by the parties.

Additionally, earn-out purchase price mechanisms are commonly used in asset deals where the value of the business asset is uncertain. Broadly, under these mechanisms, as proceeds for the sale of a target’s business assets, the vendor receives a lump-sum payment plus a right to future payments that are contingent on the performance of the business (i.e. earn-out right). The government has released a discussion paper for public consultation, proposing to treat the earn-out right as being related to the purchase of the underlying business assets (i.e. ‘look-through’ approach). The proposed treatment differs from the separate asset approach currently adopted by the ATO.

At the time of writing, while the government has indicated it may proceed to introduce the look-through approach, no exposure draft legislation has been announced or introduced.

Goodwill

Goodwill paid for a business as a going concern generally cannot be deducted or amortized.

Therefore, the purchaser may wish to have the purchase and sale agreement allocate all or most of the purchase price to the tangible assets to be acquired, thus reducing or eliminating any element of the purchase price assigned to goodwill. However, the lower price paid for goodwill also represents its cost base for CGT purposes, so this may increase the CGT exposure of the purchaser in any subsequent sale. The impact on stamp duty liabilities should also be considered.

Depreciation

Most tangible assets may be depreciated for tax purposes, provided they are used, or installed ready for use, to produce assessable income. Rates of depreciation vary depending on the effective life of the asset concerned.

Capital expenditure incurred in the construction, extension or alteration of a building that is to be used to produce income may be depreciated for tax purposes using the straight-line method, normally at the rate of 2.5 percent per year. Entitlement to this capital allowance deduction accrues to the building’s current owner, even though the current owner may not be the taxpayer that incurred the construction costs. The current owner continues to write-off the unexpired balance of the construction cost.

An important consideration in any acquisition of Australian assets or shares in an Australian company that joins a pre-existing tax-consolidated group is that, as part of the pushdown of the purchase price, depreciable assets can have their tax cost base reset to a maximum of their market value. In this scenario, any buildings acquired do not have their amortizable cost base increased, even though the tax cost base of the asset may be reset to a higher value. Capital allowances in respect of expenditure on these assets are capped at 2.5 percent per year of the original construction cost, regardless of the market value of the asset. The reset tax cost base of these assets is only relevant on a future disposal of the asset.

On the disposal of depreciable plant and equipment, the excess of the market value over the tax written-down value for each item is included in the seller’s assessable income. Conversely, where the purchase price is less than the tax written-down value, the difference is an allowable deduction to the seller.

Relatively few payments giving rise to intangible assets may be amortized or deducted for tax purposes. Presently, the main types of intangible assets that may be deducted or amortized are:

- software, including software used internally in the business, which may be amortized over 4 years

- cost of developing or purchasing patents, copyrights, or designs, which are amortized over effective life

- research and development (R&D) expenses incurred by eligible companies or partnerships of such companies

- borrowing costs, which are generally amortized over the lesser of 5 years or the term of the borrowing

- capital expenditure, which can be deducted over a 5-year period, provided the expenditure is not otherwise taken into account (by being deducted under another provision of the tax law or capitalized into the tax cost base of an asset), the deduction is not denied under another provision, and the business is carried on for a taxable purpose.

In this context, a taxable purpose broadly means for the purpose of producing assessable income in Australia. For example, expenditure incurred in setting up a new foreign subsidiary, from which the dividend income will be exempt from Australian tax, is not be considered as related to carrying on a business for a taxable purpose.

The R&D tax incentive allows a 40 percent R&D tax offset for companies with turnover of 20 million or more Australian dollars (AUD). A 45 percent refundable tax offset applies for smaller companies/groups.

Tax attributes

Tax losses and franking (imputation credits) are not transferred as a result of an asset acquisition and the cost of depreciable assets is generally allocated as discussed earlier. However, a number of other matters must be considered:

- Trading stock: The disposal of the total trading stock is not a sale in the ordinary course of the seller’s trading. Thus, the seller is required to bring to account the market value of that stock as income on the date of disposal. The purchaser is deemed to have purchased the trading stock at that value. In practice, the ATO generally accepts the price paid as the market value of the stock where the seller and buyer are dealing at arm’s length or the transaction occurs as part of a corporate group reorganization.

- Debt: Debts should not normally be acquired when the assets of a business are acquired. A deduction for bad debts is not generally available to the purchaser since the amount claimed has never been brought to account as assessable income of the claimant.

- Prepayments: When a business is acquired, it is preferable that any prepayments remain with the seller, as they may not be deductible by the purchaser.

- Employee leave provisions: Australian income tax law denies the deduction of employee leave provisions (e.g. holiday pay, long service leave). In most cases, deduction becomes available only on payment to the employee, although there are limited exceptions relating to certain employment awards where the transfer of the provision may be deductible/assessable.

- Work-in-progress: The profit arising from the sale of work-in-progress is assessable income to the seller. The purchaser is fully assessable on the subsequent realization of that work-in-progress but obtains a tax deduction for the cost of acquiring the work-in-progress.

Value added tax

The Australian equivalent of valued added tax (VAT), goods and services tax (GST), applies to ‘taxable supplies’ at a rate of 10 percent.

Disposals of assets have varying GST implications, depending on the nature of the transaction. If the sale of assets does not fall within the GST-free going concern exemption, the GST implications arising on the disposal of each asset need to be determined. A sale of assets is likely taxable, depending on the assets’ nature.

For example, the disposal of trading stock, goodwill and intellectual property is normally treated as a taxable supply. A transfer of debtors is an input taxed supply, and the GST treatment on the transfer of property depends on the nature of the property. Commercial property is generally a taxable supply, while residential property input taxed and farmland may be GST-free.

The availability of input tax credits (GST credits) to the purchaser of a taxable supply of assets depends on how the purchaser will use those assets. Generally, full credits are available where the purchaser intends to use the assets to make taxable or GST-free supplies. However, such credits may not be available where the assets are to be used to make input taxed supplies (such as financial supplies or residential leasing supplies).

Transfer taxes

The stamp duty implications of a transfer of assets depend on the nature and location (by Australian state and territory) of the assets transferred. Stamp duty is imposed by each state and territory of Australia on the transfer of certain assets. Each jurisdiction has its own revenue authority and stamp duty legislation, and exemptions, concessions and stamp duty rates differ substantially among the jurisdictions.

The assets to which stamp duty may apply in a typical acquisition of an Australian business include land and buildings (including leasehold land and improvements), chattels, debts, statutory licenses, goodwill and intellectual property. The specific types of assets subject to duty differ among the jurisdictions.

All states and territories, except Queensland, have abolished or proposed to abolish stamp duty on the transfer of certain non-real business assets, such as goodwill and intellectual property. Queensland recently announced that it will defer the abolition of such duty in the state.

The maximum rates of duty range from 4 percent to 6.75 percent of the greater of the GST-inclusive consideration and the gross market value of the dutiable property. The purchaser generally is liable to pay this duty.

Stamp duty can make reorganizations expensive. For this reason, it is often important to establish the optimum structuring of asset ownership at the outset, to avoid further payments of duty on subsequent transfers. However, most jurisdictions provide relief from duty for certain reconstructions within at least 90 percent-owned corporate groups. Such relief is subject to a number of varying conditions between the jurisdictions, including certain pre-transaction and post-transaction association requirements for group members.

Purchase of shares

Non-residents are not subject to CGT on the disposal of shares in Australian companies unless the company is considered to have predominantly invested in real property (see earlier in this chapter).

This exemption does not protect non-resident investors who hold their investments in Australian shares on revenue account. Broadly, the acquisition of shares with the primary intention of future re-sale, whether by trade sale or initial public offering (IPO), could be characterized as a revenue transaction, despite the fact that the sale would occur several years in the future. In this respect, the ATO has made determinations that affect Australian investments by resident and non-resident private equity funds.

Australia’s double taxation agreements usually apply so that non-residents disposing of shares on revenue account are not subject to Australian tax if they have no PE in Australia.

Tax indemnities and warranties

In the case of negotiated acquisitions, it is usual for the purchaser to request and the seller to provide indemnities or warranties as to any undisclosed taxation liabilities of the company to be acquired. The extent of the indemnities or warranties is a matter for negotiation. Where an acquisition is made without the agreement of the target (i.e. hostile acquisition), it is generally not possible to seek tax warranties or indemnities. Tax indemnities present special problems in addition to the usual difficulty of obtaining an effective and enforceable indemnity. These include the time delays that usually occur before a tax dispute is settled and the uncertainties in the tax law. The ATO may propose an adjustment that is acceptable to the purchaser but unacceptable to the seller.

Tax losses

Where the target company is a standalone company or the head company of an Australian tax-consolidated group, carried forward tax losses may transfer along with the company, subject to transfer and utilization rules.

Where an Australian target company has carried forward tax losses, these generally continue to be available for recoupment only if there is greater than 50 percent continuity (with respect to dividends, capital, and voting rights) in the beneficial ownership of the company. If this primary test is failed, as is usually the case in a takeover by a foreign entity, the pre-acquisition losses are available for recoupment only if the Australian company, at all times during the year of recoupment, carries on the same business as it did immediately before the change in beneficial ownership of its shares. This test is difficult to pass, because it requires more than mere similarity in the businesses carried on. Its effect is that no new types of businesses or transactions may be entered into without the likely forfeiture of the losses, particularly in the case of a tax-consolidated group.

However, provided the transfer tests are satisfied, same business losses may be refreshed on acquisition by a tax-consolidated group.

Similarly, no deduction for bad debts is available to the Australian company after its acquisition by the foreign entity unless there is either:

- more than 50 percent continuity of ownership in relation to the year the deduction is claimed and the year the debt was incurred

- continuity of the same business at relevant times.

In addition, when the target company becomes a member of the purchaser’s tax-consolidated group as a result of the transaction, the tax attributes of the company are transferred to the head company of the consolidated group (i.e. tax losses, net capital losses, franking credits and foreign tax credits). Broadly, these losses may be transferable to the acquirer where the target has satisfied the modified same business test for the 12 months prior to the acquisition. There are limitation-of-loss rules that limit the rate at which such losses can be deducted against the taxable income of the consolidated group, based on the market value of the loss-making company as a proportion of the market value of the consolidated group as a whole.

This is a complex area, and professional advice should be sought.

By contrast, where the target company is a subsidiary member of an Australian tax-consolidated group, the tax attributes of the company leaving the tax-consolidated group are retained by the head company of the tax-consolidated group and do not pass to the purchaser with the entity transferred.

Crystallization of tax charges

Under the corporate tax self-assessment regime, the ATO generally is subject to a limited review period of 4 years following the lodgment of the income tax return (except in the case of tax evasion or fraud).

Pre-sale dividend

To prevent pre-sale dividends from being distributed to reduce capital gains arising on sale of shares, the ATO has ruled that a pre-sale dividend paid by a target company to the vendor shareholder is part of the vendor shareholder’s capital proceeds for the share disposal (thereby increasing capital gain or reducing capital loss arising on the share sale), if the vendor shareholder has bargained for the dividend in return for selling the shares.

This follows the High Court of Australia decision in the Dick Smith case, in which it was held that where the share acquisition agreement stipulated that a dividend would be declared on shares prior to transfer and the purchaser was to fund the dividend (with the purchase price calculated by deducting the dividend amount), the value of the dividend formed part of the consideration for the dutiable transaction for stamp duty purposes.

In addition, complex anti-avoidance provisions also apply in this area. Specific advice should be sought to ensure these rules are complied with and avoid adverse income tax consequences.

GST

GST (VAT) does not apply to the sale of shares. The supply of shares is a ‘financial supply’ and input taxed if sold by a vendor in Australia to a purchaser in Australia. However, if the shares are sold to, or bought from, a non-resident that is not present in Australia, the sale may be a GST-free supply.

While GST should not apply in either event, the distinction between an input taxed supply and a GST-free supply is important from an input tax credit-recovery perspective. Generally, full credits are not available for GST incurred on costs associated with making input taxed supplies, but full credits are available for GST-free supplies.

Stamp duty

New South Wales and South Australia impose state stamp duty on transfers of unlisted shares and units in unit trust schemes at the marketable securities rate of 60 cents per AUD100 of the greater of the consideration and unencumbered value of the shares or units. Stamp duty at the marketable securities rate is not imposed on transfers of listed shares or units.

All states and territories impose land-rich or landholder duty on relevant acquisitions of interests in land-rich or landholder companies and trusts. The tests for whether an entity is land-rich or a landholder differ between the jurisdictions.

In some jurisdictions, landholder duty is also imposed on certain takeovers of listed landholders. Land-rich and landholder duty is imposed at rates up to 6.75 percent of the value of the land (land and goods in some states) held by the landholder. A concessional rate of duty applies to takeovers of listed landholders in some but not all states (the concessional rate is 10 percent of the duty otherwise payable).

The acquirer generally is liable to pay stamp duty.

Tax clearances

It is not possible to obtain a clearance from the ATO by giving assurances that a potential target company has no arrears of tax or advising as to whether or not it is involved in a tax dispute.

Where the target company is a member of an existing tax-consolidated group, the purchaser should ensure the target company is no longer liable for any outstanding tax liabilities of the existing tax-consolidated group (e.g. if the head company of that group defaults). The purchaser should ensure that the target company:

- is party to a valid tax sharing agreement with the head company and other members of the existing group, which reasonably limits the target company’s exposure to its own standalone tax liabilities

- exits the existing group clear of any outstanding group liabilities by attaining evidence that the existing company made an exit payment to the head company of the tax-consolidated group.

The ATO has a detailed receivables policy that sets out its approach in recovering outstanding group tax liabilities from an exiting company. The purchaser should bear this in mind when assessing the tax position of the target company.

Choice of acquisition vehicle

After the choice between the purchase of shares or assets has been made, the second decision concerns the vehicle to be used to make the acquisition and, as a consequence, the position of the Australian operations in the overall group structure. The following vehicles may be used to acquire the shares or assets of the target:

- foreign company

- Australian branch of the foreign company

- special-purpose foreign subsidiary

- treaty country intermediary

- Australian holding company

- joint venture

- other special purpose vehicle (e.g. partnership, trust or unit trust).

The structural issues in selecting the acquisition vehicle can usually be divided into two categories:

- the choice between a branch or a subsidiary structure for the acquired Australian operations

- whether there are, in the circumstances, advantages to interposing an intermediary company as the head office for the branch or the holding company for the subsidiary.

Local holding company

It is common to interpose an Australian holding company between a foreign company (or third-country subsidiary) and an Australian subsidiary. The Australian holding company may act as a dividend trap because it can receive dividends free of further Australian tax and re-invest these funds in other group-wide operations. It is common to have an Australian holding company act as the head entity of a tax-consolidated group.

Foreign parent company

Where the foreign country of the parent does not tax capital gains, it may wish to make the investment directly. Non-residents are not subject to CGT on the disposal of shares in Australian companies unless the company is considered to have predominantly invested in real property (see earlier). However, while Australian interest WHT is generally 10 percent for both treaty and non-treaty countries, the dividend WHT is commonly limited to 15 percent on profits that have not been previously taxed (referred to as unfranked or partly franked dividends – see the information on preserving imputation credits within this chapter’s section on other considerations) only when remitted to treaty countries. (Australia’s more recent treaties may reduce this rate further if certain conditions are satisfied.)

The dividend WHT rate is 30 percent for unfranked dividends paid to non-treaty countries. The tax on royalties paid from Australia is commonly limited to 10 percent for treaty countries (30 percent for non-treaty countries). Therefore, an intermediate holding company in a treaty jurisdiction with lower WHT rates may be preferred, particularly if the foreign parent is unable fully to offset the WHT as a foreign tax credit in its home jurisdiction (subject to limitation of benefit clauses in tax treaties).

Non-resident intermediate holding company

If the foreign country imposes tax on capital gains, locating the subsidiary in a third country may be preferable. The third-country subsidiary may also sometimes achieve a WHT advantage if the foreign country does not have a tax treaty with Australia. While Australian interest WHT is generally 10 percent for both treaty and non-treaty countries, the dividend WHT is commonly limited to 15 percent on untaxed profits (unfranked or partly franked dividends; again, see the information about preserving imputation credits) only when remitted to treaty countries. (Australia’s more recent treaties may reduce this rate further if certain conditions are satisfied.)

The dividend WHT rate is 30 percent for unfranked dividends paid to non-treaty countries. The tax on royalties paid from Australia is commonly limited to 10 percent for treaty countries (30 percent for non-treaty countries). Thus, where the third-country subsidiary is located in a treaty country, these lower WHT rates may be obtained. Note, however, that some treaties contain anti-treaty shopping rules. As noted, the ATO has ruled in a taxation determination that the Australian domestic GAARs would apply to inward investment private equity structures designed with the dominant purpose of accessing treaty benefits. The taxation determination demonstrates the ATO’s enhanced focus on whether investment structures (e.g. the interposition of holding companies in particular countries) have true commercial substance and were not designed primarily for tax benefits.

A key consideration in this regard is to ensure the payee beneficially owns the dividends or royalties. Beneficial entitlement is a requirement in most of Australia’s treaties.

Local branch

Forming a branch may not seem to be an option where shares, rather than assets, are acquired, since, in effect, the foreign entity has acquired a subsidiary. However, if the branch structure is desired but the direct acquisition of assets is not possible, the assets of the newly acquired company may be transferred to the foreign company post-acquisition, effectively creating a branch. Great care needs to be taken when creating a branch from a subsidiary in this way, including consideration of the availability of CGT rollover relief, potential stamp duties and the presence of tax losses.

However, a branch is not usually the preferred structure for the Australian operations. Many of the usual advantages of a branch do not exist in Australia:

- There are no capital taxes on introducing new capital either to a branch or to a subsidiary.

- No WHT applies on taxed branch profits remitted to the head office or on dividends paid out of taxed profits (i.e. franked dividends, discussed later in the section on preserving imputation credits) from an Australian subsidiary.

- The profits of an Australian branch of a non-resident company are taxed on a normal assessment basis at the same rate as the profits of a resident company.

The branch structure has one main potential advantage. Where the Australian operations are likely to incur losses, in some countries, these may be offset against domestic profits. However, the foreign acquirer should consider that deductions for both royalties and interest paid from branches to the foreign head office, and for foreign exchange gains and losses on transactions between the branch and head office, are much more doubtful than the equivalents for subsidiaries, except where it can be shown that the payments are effectively being made to third parties.

The only provisions that might restrict the deduction for a subsidiary are the arm’s length pricing rules applicable to international transactions and the thin capitalization provisions.

Reorganizations and expansions in Australia are usually simpler where an Australian subsidiary is already present.

An Australian subsidiary would probably have a much better local image and profile and gain better access to local finance than a branch. The repatriation of profits may be more flexible for a subsidiary, as it may be achieved either by dividends or by eventual capital gain on sale or liquidation. This can be especially useful where the foreign country tax rate is greater than 30 percent; in such cases, the Australian subsidiary may be able to act as a dividend trap. Finally, although Australian CGT on the sale of the subsidiary’s shares might be avoided, this is not possible on the sale of assets by a branch, which is, by definition, a PE.

Two other frequently mentioned advantages of subsidiaries are limited liability (i.e. inaccessibility of the foreign company’s funds to the Australian subsidiary’s creditors) and possible requirements for less disclosure of foreign operations than in the branch structure. However, both these advantages can also be achieved in Australia through the use of a branch, by interposing a special-purpose subsidiary in the foreign country as the head office of the branch.

Joint venture

Where the acquisition is to be made together with another party, the parties must determine the most appropriate vehicle for this joint venture. In most cases, a limited liability company is preferred, as it offers the advantages of incorporation (separate legal identity from that of its members) and limited liability (lack of recourse by creditors of the Australian operations to the other resources of the foreign company and the other party). Where the foreign company has, or proposes to have, other Australian operations, its shareholding in the joint venture company are usually held by a separate wholly owned Australian subsidiary, which can be consolidated with the other operations.

It is common for large Australian development projects to be operated as joint ventures, especially in the mining industry. Where the foreign company proposes to make an acquisition in this area, it usually must decide whether to acquire an interest in the joint venture (assets) or one of the shares of the joint ventures (usually, a special-purpose subsidiary). This decision and decisions relating to the structuring of the acquisition can usually be made in accordance with the preceding analysis.

Choice of acquisition funding

Where a purchaser uses an Australian holding company in an acquisition, the form of this investment must be considered. Funding may be by way of debt or equity. A purchaser should be aware that Australia has a codified regime for determining the debt or equity classification of an instrument for tax purposes. This is, broadly, determined on a substance-over-form basis.

Debt

Generally, interest is deductible for income tax purposes (subject to commentary below), but dividends are not. Additionally, the non-interest costs incurred in borrowing money for business purposes, such as the costs of underwriting, brokering, legal fees and procurement fees, may be written-off and deducted over the lesser of 5 years or the term of the borrowing.

Whether an instrument is debt or equity for tax purposes is a key consideration in implementing a hybrid financing structure, discussed later.

Deductibility of interest

Interest payable on debt financing is generally deductible in Australia, provided the borrowed funds are used in the assessable income-producing activities of the borrower or to fund the capitalization of foreign subsidiaries. No distinction is made between funds used as working capital and funds used to purchase capital assets.

The major exceptions to this general rule are as follows:

- Where the thin capitalization rules are breached, a portion of the interest is not deductible.

- Interest expenses incurred in the production of certain tax-exempt income are not deductible.

- Interest expenses incurred in the holding of a capital asset are not deductible where the only prospective assessable income in Australia is the capital gain potentially available on sale (the interest expenses may be included in the cost base for CGT purposes).

The thin capitalization rules apply to inbound investing entities with respect to all debt that gives rise to tax deductions. These rules deny interest deductions where the average amount of debt of a company exceeds both the safe harbor debt amount and the alternative arm’s length debt amount.

The safe harbor debt amount is essentially 75 percent of the value of the assets of the Australian company, which is debt-to-equity ratio of 3:1. For financial institutions, this ratio is increased to 20:1. The arm’s length debt amount is the amount of debt that the Australian company could reasonably be expected to have borrowed from a commercial lending institution dealing at arm’s length. As mentioned in the recent developments section above, the Australian government has proposed to reduce the Australian thin capitalization thresholds for income years beginning on or after 1 July 2014.

The thin capitalization rules, subject to additional safe harbors, also apply to Australian groups operating overseas (outbound investing entities) in addition to Australian entities that are foreign-controlled and Australian operations of foreign multinationals.

As the thin capitalization rules apply with respect to all debt that gives rise to tax deductions, no distinction is made between internal and external financing or between local and foreign financing.

Withholding tax on debt and methods to reduce or eliminate it

Australia generally imposes WHT at 10 percent on all payments of interest, including amounts in the nature of interest (e.g. deemed interest under hire purchase agreements or discounts on bills of exchange). The 10 percent rate applies to countries whether or not Australia has concluded a tax treaty with the country in question. However, the applicable interest WHT rate may be reduced on certain interest payments to financial institutions to 0 percent by some of Australia’s more modern tax treaties (including the treaties with United States, United Kingdom, France and Japan). Few techniques to eliminate WHT on interest are available.

Interest paid on widely held debentures issued outside Australia for the purpose of raising a loan outside Australia are exempt from WHT where the interest is paid outside Australia. As Australian WHT cannot usually be avoided, the acquisition should be planned to ensure that credit is available in the country of receipt.

Australia does not impose WHT on franked dividends. Australia imposes WHT with respect to the unfranked part of a dividend at a rate that varies from 15 percent, the usual rate in Australia’s treaties, to 30 percent for all non-treaty countries. In the case of the US and UK treaties, the rate of dividend withholding may be as low as 0 percent.

Australia is progressively renegotiating its tax agreements with its preferred trading partners with a view to extending the 0 percent concessional WHT rate.

Checklist for debt funding

- Interest WHT at 10 percent ordinarily applies to cross-border interest, except to banks in the UK and US, unless the interest is paid in relation to a publicly offered debenture.

- Third-party and related-party debt are treated in the same manner for Australian thin capitalization purposes.

- Interest expense in a financing vehicle can be offset against income of the underlying Australian business when it is part of an Australian tax-consolidated group.

Equity Scrip-for-scrip relief

Equity is another alternative for funding an acquisition. This may take the form of a scrip-for-scrip exchange whereby the seller may be able to defer any gain, although detailed conditions must be satisfied.

The main conditions for rollover relief to be available include:

- All selling shareholders can participate in the scrip-for-scrip exchange on substantially the same terms.

- Under the arrangement, the acquiring entity must become the owner of 80 percent or more of the voting shares in the target company, or the arrangement must be a takeover bid or a scheme of arrangement approved under the Corporations Act 2001.

- The selling shareholders hold their shares in the target company on capital account (i.e. the shares are not trading stock).

- The selling shareholders acquired their original shares in the target company on or after 20 September 1985.

- Apart from the rollover, the selling shareholders would have a capital gain on the disposal of their shares in the target company as a result of the exchange.

Additional conditions apply where both the target company and the purchaser are not widely held companies or where the selling shareholder, target company and purchaser are commonly controlled.

Where the selling shareholders receive only shares from the acquiring company (the replacement shares) in exchange for the shares in the target company (the original shares) and elect for scrip-for-scrip rollover relief, they are not assessed on any capital gain on the disposal of their original shares at the time of the acquisition. Any capital gain on the shares is taxed when they dispose of their replacement shares in the acquiring company. Where the sellers receive both shares and other consideration (e.g. cash), only partial CGT rollover is available. The cost base of the original shares is apportioned on a reasonable basis between the replacement shares and the other consideration, and the selling shareholders are subject to CGT at the time of the share exchange to the extent that the value of the other consideration received exceeds the allocated portion of the original cost base of the original shares.

Where the selling shareholders acquired their original shares prior to 20 September 1985 (pre-CGT shareholders), subject to transitional provisions, the selling shareholders are not subject to CGT on the disposal of the original shares, so they do not require rollover relief. However, such shareholders lose their pre-CGT status, and as a result they are subject to CGT on any increase in the value of the replacement shares between the acquisition and subsequent disposal of the replacement shares. The cost base of the replacement shares that a pre-CGT shareholder receives is the market value of those shares at the time of issue.

Provided the target company or the purchaser is a widely held company, the cost base of the shares in the target company that are acquired by the purchaser is the market value of the target company at the date of acquisition. The CGT cost base of the target shares acquired by the purchaser is limited to the selling shareholders’ cost base in the target company (i.e. no step-up to market value is available) if there is:

- a substantial shareholder who holds a 30 percent or more interest (together with associates) in the target company

- common shareholders in the target company and the purchaser company, who, together with associates, hold an 80 percent or more interest in the target company prior to the acquisition and an 80 percent or more interest in the purchaser after the acquisition, or

- a ‘restructure’ under the scrip-for-scrip arrangement rather than a genuine takeover.

Generally, a company is widely held if it has at least 300 members. Special rules prevent a company from being treated as widely held if interests are concentrated in the hands of 20 or fewer individuals.

Demerger relief

Demerger relief rules are also available to companies and trusts where the underlying ownership of the divested membership interests in a company is maintained on a totally proportionate basis. These rules are not available to membership interests held on revenue account. In an M&A context, there are safeguards in the anti-avoidance provisions to prevent demergers from occurring where transactions have been pre-arranged to effect change in control.

This is a focus area of the ATO, so transactions of this nature are generally subject to advance rulings.

The demerger relief available is as follows:

- CGT relief at the shareholder level providing for cost base adjustments between the original membership interests and the new membership interests

- CGT relief at the corporate level providing for a broad CGT exemption for the transfer or cancellation of membership interests in the demerged entity

- deeming the divestment of shares to shareholders not to be a dividend, subject to anti-avoidance rules.

Dividend imputation rules

Australia operates an imputation system of company taxation through which shareholders of a company gain relief against their own tax liability for taxes paid by the company.

Resident companies must maintain a record of the amount of their franking credits and franking debits to enable them to ascertain the franking account balance at any point in time, particularly when paying dividends. This franking account is a notional account maintained for tax purposes and reflects the amount of company profits that may be distributed as franked dividends.

Detailed rules determine the extent to which a dividend should be regarded as franked. A dividend may be partly franked and partly unfranked. Generally, a dividend is franked where the distributing company has sufficient taxed profits from which to make the dividend payment and the dividend is not sourced from the company’s share capital. As noted, the ATO has released a draft taxation ruling expressing its preliminary views on when dividends paid would be frankable for tax purposes under the dividend requirements of the recently amended Corporations Act.

Dividends paid to Australian resident shareholders carry an imputation rebate that may reduce the taxes payable on other income received by the shareholder. Additionally, shareholders who are Australian-resident individuals and complying superannuation funds can obtain a refund of excess franking credits.

For non-resident shareholders, however, franked dividends do not result in a rebate or credit, but instead are free of dividend WHT (to the extent to which the dividend is franked).

No dividend WHT is levied on dividends paid by a resident company to its resident shareholders. Tax assessed to an Australian-resident company generally results in a credit to that company’s franking account equivalent to the amount of taxable income less tax paid thereon.

The franking account balance is not affected by changes in the ownership of the Australian company. As non-resident companies do not obtain franking credits for tax paid, an Australian branch has no franking account or capacity to frank amounts remitted to a head office.

Hybrids

Due to Australia’s thin capitalization regime, a purchaser usually finances through a mix of debt and equity and may consider certain hybrid instruments. Australia does not impose stamp duty on the issue of new shares in any state, and there is no capital duty.

As noted earlier in this chapter, the characterization of hybrids (e.g. convertible instruments, preferred equity instruments and other structured securities) as either debt or equity is governed by detailed legislative provisions that have the overriding purpose of aligning tax outcomes to the economic substance of the arrangement.

These provisions contain complex, inter-related tests that, in practice, enable these instruments to be structured such that subtle differences in terms can decisively alter the tax characterization in some cases. Examples of terms that can affect the categorization of an instrument include the term of the instrument, the net present value of the future obligations under the instrument and the degree of contingency/certainty surrounding those obligations.

Additionally, the debt/equity characterization of hybrid instruments under the Australian taxation law and that under foreign taxation regimes have been subject to enhanced scrutiny by the ATO and foreign revenue authorities. The application of an integrity provision that deems an interest from an arrangement that funds a return through connected entities to be an equity interest (and hence causes returns to not be deductible) under certain circumstances should be considered in this context.

Accordingly, the careful structuring of hybrid instruments is a common focus in Australian business finance. In some cases, this focus extends to cross-border hybrids, which are characterized differently in different jurisdictions.

Discounted securities

Historically, a complex specific statutory regime has applied that broadly, seeks to tax discounted securities on an accruals basis. This treatment is essentially be preserved under the Taxation of Financial Arrangements (TOFA) provisions, which are broadly intended to align the tax treatment of financial arrangements with the accounting treatment. Note that interest WHT at 10 percent may apply when such a security is transferred for more than its issue price.

Deferred settlement

Where settlement is deferred on an interest-free basis, any CGT liability accruing to the seller continues to be calculated from the original disposal date and on the entire sale proceeds.

Where interest is payable under the settlement arrangement, it does not form part of the cost base. Rather, it is assessable to the seller and deductible to the purchaser to the extent that the assets or shares are capable of producing assessable income, other than the prospective capital gain on resale.

As noted earlier, the taxation of earn-outs in Australia is in a state of flux. The ATO has issued a draft ruling that advocated a treatment that is contrary to longstanding practice, and the government released a discussion paper outlining a proposed treatment that differs from that of the ATO.

Concerns of the seller

Non-residents are broadly exempt from CGT in respect of the disposal of Australian assets held on capital account, including a disposal of shares in a company or interests in a trust. The key exception is where a non-resident has a direct or indirect interest in real property, which is defined broadly to include leasehold interests, fixtures on land and mining rights. The provisions that seek to apply CGT in these circumstances are extremely broad and carry an extraterritorial application in that non-residents disposing of interests in upstream entities that are not residents of Australia may also be subject to CGT.

The CGT exemption for non-residents does not apply to assets used by a non-resident in carrying on a trade or business wholly or partly at or through a PE in Australia.

Where a purchase of assets is contemplated, the seller’s main concern is likely to be the CGT liability arising on assets acquired after 19 September 1985. Where the sale is of a whole business or a business segment that was commenced prior to CGT, the seller normally seeks to allocate as much of the price as possible to goodwill, because payment for goodwill in these circumstances is generally free from Australian income tax, unless there has been a majority change in underlying ownership of the assets.

The CGT liability may also be minimized by favorably spreading the overall sale price of the assets in such a way that above-market prices are obtained for pre-CGT assets and below-market prices obtained for post-CGT assets. Such an allocation may be acceptable to the purchaser because it may not substantially alter the CGT on sales. However, the prices for all assets should be justifiable; otherwise, the ATO may attack the allocation as tax avoidance. The purchaser would also be keen to review the allocation, with particular reference to those assets that have the best prospects for future capital gains.

The seller is concerned about the ability to assess the amount of depreciation recouped where depreciable assets (other than buildings) are sold for more than their tax written-down value.

The excess of consideration over the tax written-down value is included in assessable income in the year of sale as a balancing adjustment and taxed according to the normal income tax rules. Where a depreciable building is sold, no such balancing adjustment is generally made. Where a depreciable asset (other than a building) is sold for less than its tax written-down value, the loss is deductible as a balancing deduction in the year of sale. This balancing deduction is not treated as a capital loss.

Strictly speaking, the seller is also required to include as assessable income the market value of any trading stock sold, even though a different sale price may be specified in the sale agreement. As noted earlier, the ATO’s usual practice is to accept the price paid as the market value.

Stamp duty is payable by the purchaser but inevitably affects the price received by the seller.

GST considerations are also relevant to the seller. As noted above, the sale of assets may be a taxable supply unless the sale qualifies as the GST-free supply of a going concern. Where the going concern exemption is not available, the types of assets being transferred need to be considered to determine whether GST applies. While the sale and purchase of shares does not attract GST, full input tax credits may not be available for GST incurred on transaction costs associated with the sale or purchase. For some costs, a reduced input tax credit may be available for certain prescribed transaction costs.

Where the seller company has carrried forward losses, the sale of business assets does not ordinarily jeopardize its entitlement to recoup those losses. However, the seller company may be relying on satisfaction of the same-business test (see this chapter’s information on using pre-acquisition losses) to recoup the losses (for example, due to changes in the ownership of the seller since the year(s) of loss). Care is then required, as the sale of substantial business assets could jeopardize satisfaction of this test and lead to forfeiture of the losses.

Where a purchase of shares is contemplated, the seller may have several concerns, depending on the seller’s situation. Potential concerns include the following:

- Current or carried forward losses remain with the company, so they are unavailable to the seller where the shares in the company are sold. If the seller currently has an entitlement to such losses without recourse to the same-business test, this entitlement is not forfeited when the business assets are sold, and the seller may be able to inject new, profitable business to recoup these losses. However, where the target company is included within the seller’s tax-consolidated group prior to sale, the seller retains the tax losses.

- Where the seller acquired all or part of its shareholding after 19 September 1985, the sale of shares has CGT consequences, and a capital gain or loss may accrue. Where the acquisition is achieved by way of a share swap, CGT rollover relief may be available. Where the target company forms part of the seller’s tax-consolidated group, the seller is treated as if it disposed of the assets of the target company; any gain is calculated as the excess of the sale proceeds over the tax cost base of the assets (less liabilities) of the target company. Where the liabilities of the target company exceed the tax cost base of the target’s assets, a deemed capital gain arises for the seller.

- The purchaser may request indemnities or warranties (usually subject to negotiation).

- Any gain on the sale of pre-CGT shares may also be assessable where the seller is dealing in shares or where the seller purchased the shares with either the intention of sale at a profit or as part of a profit-making endeavor.

- In the case of shares in a private company or interest in a private trust acquired before 19 September 1985, where the value of the underlying assets of the company or trust that has been acquired after 19 September 1985 represents 75 percent or more of the net worth of the company or trust, CGT may be payable.

Company law and accounting

Corporations Act 2001 and IFRS

The Australian Corporations Act 2001 governs the types of company that can be formed, ongoing financial reporting and external audit requirements, and the repatriation of earnings (either as dividends or returns of capital).

Australian accounting standards are the equivalent of International Financial reporting Standards (IFRS). The acquisition of a business, regardless of whether it is structured as a share acquisition or asset acquisition, is accounted for using purchase accounting.

Under purchase accounting, all identifiable assets and liabilities are recognized at their respective fair values on the date that control of the business is obtained. Identifiable assets may include intangible assets that are not recognized on the target’s balance sheet. These intangible assets may have limited lives and require amortization. In a business combination, liabilities assumed include contingent liabilities, which are also recognized on the balance sheet at their estimated fair value. The difference between consideration paid (plus the balance of non-controlling interest at acquisition date and the acquisition date fair value of the acquirer’s previous interest in the acquire) and the ownership interest in the fair value of acquired net assets represents goodwill. Goodwill is not amortized but is tested for impairment annually. Any negative goodwill is recognized immediately in the income statement.

Transaction costs associated with business combinations occurring in fiscal years commencing on or after 1 July 2009 are expensed as incurred. The reorganization of businesses under the control of the same parent entity is outside the scope of accounting standards. Typically, these restructurings occur at book values, with no change in the carrying value of reported assets and liabilities and no new goodwill. Again, transaction costs associated with these common control transactions are generally expensed as incurred.

Reporting obligations

Generally, all substantial Australian companies have an obligation to file audited financial statements with the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC). ASIC monitors compliance with the Australian Corporations Act. These financial statements are publicly available. Filing relief may be available for subsidiaries of other Australian entities.

Payment of dividends

The payment of dividends by companies to their shareholders is governed by the Australian Corporations Act in conjunction with the accounting standards and taxation law.

In 2010, amendments were made to the dividend requirements in the Australian Corporations Act. This act now provides that a company cannot pay a dividend to its shareholders unless its assets exceed its liabilities at the time of declaring the dividend and certain shareholder and creditor fairness tests are satisfied. This requirement has replaced the former profits-based test, which provided that a company can only pay a dividend out of profits.

The assessment of available profit and declaration of dividends is determined on a standalone, legal-entity-by-legal-entity basis, not the consolidated position. This entity-by-entity assessment requires planning to avoid dividend traps, that is, the inability to stream profits to the ultimate shareholder due to insufficient profits within a chain of companies. Appropriate pre-acquisition structuring helps minimize this risk. Australian law does not have a concept of par value for shares. The Australian Corporations Act prescribes how share capital can be reduced, including restrictions on the redemption of redeemable preference shares.

Other considerations

Group relief/consolidation

Where the purchaser owns other Australian companies and has elected to form an Australian tax-consolidated group, the target company becomes a subsidiary member on acquisition. Only wholly owned subsidiaries can join an Australian tax-consolidated group.

Issues that arise as a result of the tax-consolidation regime with respect to share acquisitions are as follows:

- A principle underlying the tax-consolidation regime is the alignment of the tax value of shares in a company with its assets. On acquisition, it may be possible to obtain a step-up in the tax value of assets of the newly acquired subsidiary when it joins a consolidated group by pushing down the purchase price of the shares to the underlying assets. The acquiring company is effectively treated as purchasing the assets of the target company, including any goodwill reflected as a premium in the share price above the value of the net assets of the company.

- Because the tax basis of a target’s CGT assets is reset, the acquiring company can dispose of unwanted CGT assets acquired as part of the acquisition with no tax cost. As discussed above, the government has released a discussion paper with proposals to limit the deductibility of rights to future income assets. These rules will apply retrospectively and prospectively, so the impact of these changes on past and future transactions should be considered.

- Each corporate member of a tax-consolidated group or GST group is jointly and severally liable for the tax and GST liabilities of the whole group. As noted above, this liability can be limited where the companies within the group enter into a tax sharing agreement. When acquiring a company that formed part of a tax-consolidated group, it is important to determine the extent of its exposure for the tax liabilities of its previous tax-consolidated group and mechanisms to reduce this exposure.

- Where an Australian entity is acquired directly by a foreign entity and the foreign entity has other Australian subsidiaries that have formed a tax-consolidated group, there is an irrevocable choice as to whether or not to include the newly acquired Australian entity in the tax-consolidated group. Alternatively, where the Australian entity is acquired by an existing Australian entity that forms part of a tax-consolidated group, the newly acquired Australian entity is automatically included in the existing group.

- The historical tax expense and cash flow of the target company is no longer a valid indicator for projecting future cash tax payments. The resetting of the tax base in the assets of the company makes tax modeling for the cash outflows more important.

Transfer pricing

Australia has a complex regime for the taxation of international related-party transactions. These provisions specify significant contemporaneous documentation and record-keeping requirements.

As mentioned in the section on recent developments earlier in this chapter, the Australian government has enacted new transfer pricing rules that are intended to modernize Australia’s transfer pricing provisions and align them with international standards. The new rules focus on determining an arm’s length profit allocation. The new rules also provide the Commissioner of Taxation with broad powers of reconstruction in respect of international related-party dealings.

Dual residency

Dual residency is unlikely to give rise to any material Australian tax benefits and could significantly increase the complexity of any transaction.

Foreign investments of a local target company

Where an Australian target company holds foreign investments, the question arises as to whether those investments should continue to be held by the Australian target company or whether it would be advantageous for a sister or subsidiary company of the foreign acquirer to hold the foreign investments.

Australia has a comprehensive international tax regime that applies to income derived by controlled foreign companies (CFC). The objective of the regime is to place residents who undertake certain passive or related party income earning activities offshore on the same tax footing as residents who invest domestically.

Under the current CFC regime, an Australian resident is taxed on certain categories of income derived by a CFC if the taxpayer has an interest in the CFC of 10 percent or more. A CFC is broadly defined as a foreign company that is controlled by a group of not more than five Australian residents whose aggregate controlling interest in the CFC is not less than 50 percent. However, a company may also be a CFC in certain circumstances where this strict control test is not met but the foreign company is in effect controlled by five or fewer Australian residents.

Taxpayers subject to the current CFC regime must calculate their income by reference to their interest in the CFC. The income is then attributed to the residents holding the interest in the CFC in proportion to their interests in the company – that is, the Australian resident shareholders are subject to tax in Australia on their share of the attributable earnings of the CFC.

Any income of a CFC that has been subjected to foreign or Australian tax can offset that amount with a credit against Australian tax payable. Excess credits may be carried forward for up to 5 income years. The income of a CFC generally is not attributed where the company is predominantly involved in actively earning income.

Given the comprehensive nature of the CFC regime and the few exemptions available, the Australian target company may not be the most tax-efficient vehicle to hold international investments. However, due to a recent series of reforms relating to conduit relief, Australia is now a favorable intermediary holding jurisdiction. In particular, Australia now has broad participation exemption rules that enable dividend income sourced from offshore subsidiaries and capital profits on realization of those subsidiaries to be paid to non-resident shareholders free from domestic income tax or non-resident WHT.

Comparison of asset and share purchases

Advantages of asset purchases

- Step-up in the tax value of assets.

- A deduction is available for trading stock purchased.

- No previous liabilities of the company are inherited.

- Possible to acquire only part of a business.

- Not subject to takeover legislation (but may be subject to stock exchange listing rules).

Disadvantages of asset purchases

- Complexity of renegotiating/transferring supply, employment, technology and other agreements.

- Higher rates of transfer (stamp) duties.

- Benefit of any losses incurred by the target company remains with the seller.

- Need to consider whether the GST going concern exemption is available.

Advantages of share purchases

- Lower capital outlay (purchase net assets only).

- Potential to step-up the tax value of assets in a 100 percent acquisition.

- Less complex contractually and likely more attractive to seller.

- May benefit from tax losses of the target company (unless the target company was a member of a tax-consolidated group).

- Lower or no stamp duties payable (if not predominantly land).

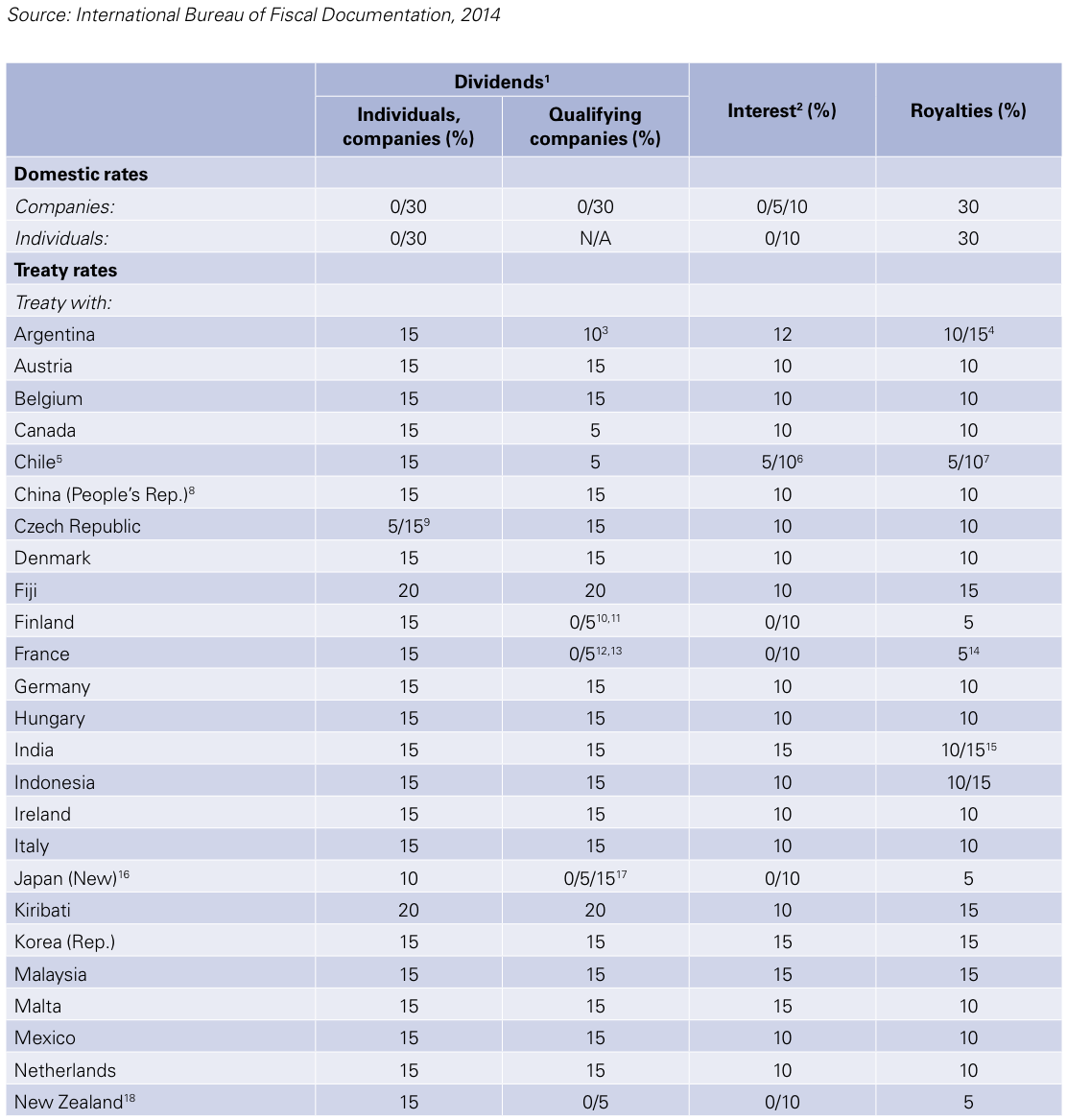

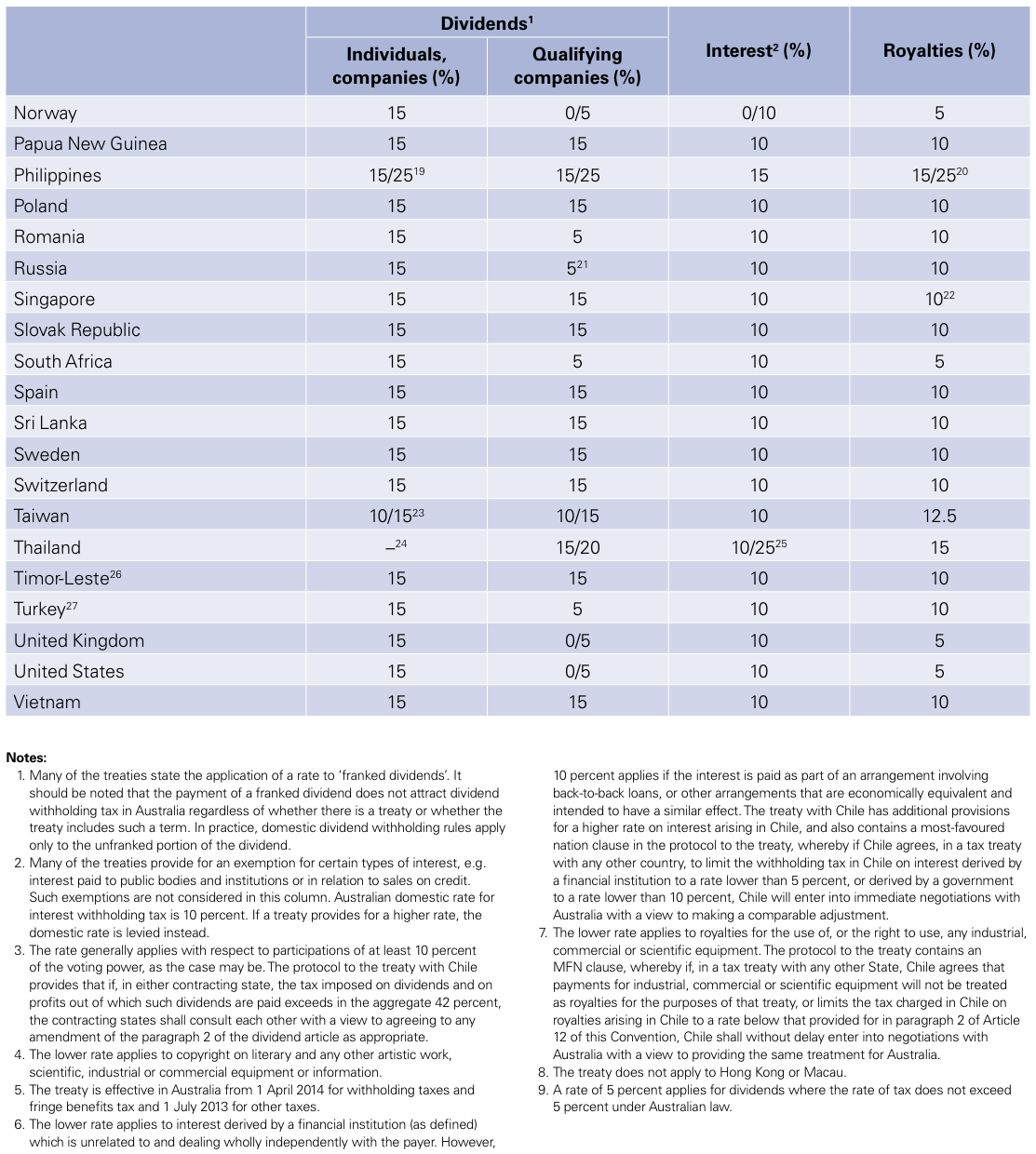

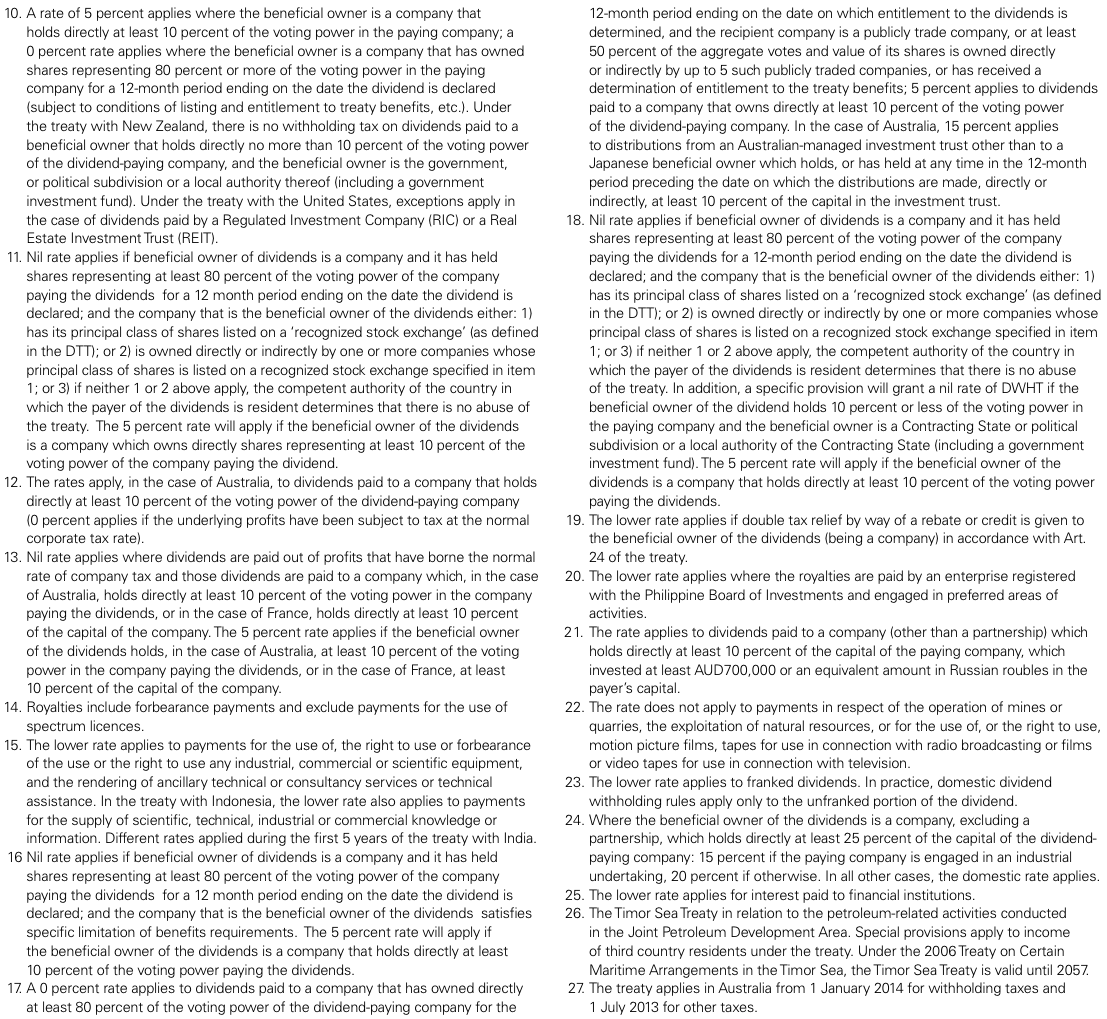

Australia – Withholding tax rates

This table sets out reduced WHT rates that may be available for various types of payments to non-residents under Australia’s tax treaties. This table is based on information available up to 1 November 2013.